NJCIE 2017, Vol. 1(1), 68-84

http://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.1952

Mediation, Collaborative Learning and Trust in Norwegian School Governing: Synthesis from a Nordic Research Project

Jan Merok Paulsen[1]

Associate Professor, Oslo and Akershus University of Applied Sciences

Øyvind Henriksen

PhD Candidate, Oslo and Akershus University of Applied Sciences

Copyright the authors

Peer-reviewed article; received 8 February 2017; accepted 28 June 2017

Abstract

This paper analyses productive patterns through which school superintendents and subordinated principals collaborate at the local levels of implementation in the Nordic countries. The underlying theoretical premise is that the school governance systems in the Nordic countries, as a function of strengthened state steering and a variety of local political conditions, entail a series of loose couplings—described by the broken chain metaphor. The analysis is based on a review of findings from a comparative Nordic research project. The review reveals that school superintendents and principals to a large extent activate professional learning forums as integration mechanism—to make collective sense of ambiguous national reforms. Important learning conditions that emerge from the country reports, on which the reviewed research is based, seem to cluster and cohere around learning climate, interpersonal trust, leadership support and a shared knowledge base between the school leaders and the municipal apparatus. Implications for research and practice are discussed.

Keywords: School governance; school leadership; professional development; interpersonal trust

Introduction

During the last decades, there has been a broad consensus among scholars and educational practitioners, across a range of different education systems, that school districts play an important role in collaboration with school leaders in order to develop schools as better learning systems (Leithwood, 2000; Leithwood & Louis, 1998). From this perspective, the relationship between school district administrators, school district politicians, and school principals becomes critical links for school development and system capacity building (Louis, 2015). School principals need to “deal with uncertainty and ‘think on their feet’; they need to be ready with creative responses to problems and to opportunities. This isn’t an individual task” (Stoll & Temperley, 2009, p. 17). Furthermore, there is evidence that school leaders who reported being part of district leader networks, essentially professional communities for leaders, were more likely to be viewed as effective instructional leaders by their teachers (Lee, Louis, & Anderson, 2012).

In the Nordic countries, municipalities correspond fairly closely with school districts in other systems. Thus, municipalities constitute the meso-level in the Nordic national school governance systems. During the post-World War II period,

formal authority in the Nordic educational systems has been envisaged and structured as a straight line from one level, elected politicians and appointed practitioners/administrators, to the other levels: From parliament and government, through the municipal council and administration, to school board and school leaders. (Moos, Nihlfors, & Paulsen, 2016a, p. 2)

However, since the 1990s a range of “broken chains” (Moos, Nihlfors, & Paulsen, 2016b), often conceived as loose couplings in the governing line (Paulsen & Moos, 2014), has been observed, which leaves school principals, local politicians and municipal school superintendents to work together in collaborative structures and professional networks—at the purpose of school improvements (Paulsen, Nihlfors, Brinkkjær, & Risku, 2016; Rhodes, 1997).

The current article follows this line of reasoning by focusing on the relationship between school leaders and their municipal school owners in four Nordic countries; Finland, Denmark, Sweden, and Norway. Specifically, the relationship between the school superintendent and his or her group of school leaders, to which the superintendent is superior, is highlighted as critical and will be subjected to our analysis. We also bring in supplemental information about the relationships between school boards and superintendents, and between school boards and school leaders. The analysis takes the form of a review of prior published work in journal articles, book chapters, and peer-reviewed conference papers, based mainly on findings drawn from a large-scale Nordic research project undertaken from 2009 to 2014. During the research process, data from Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark were collected from school board members, superintendents, and school principals through joint survey instruments, and findings have been published in articles and books, on which this current review is based. Examples of response patterns and frequencies are mainly drawn from the Norwegian part of the project, yet the Swedish, Danish and Finish descriptive country reports deviate only to a small extent, and in those cases, exceptions are specifically commented upon.

Theoretical framework

Significance of school district governance

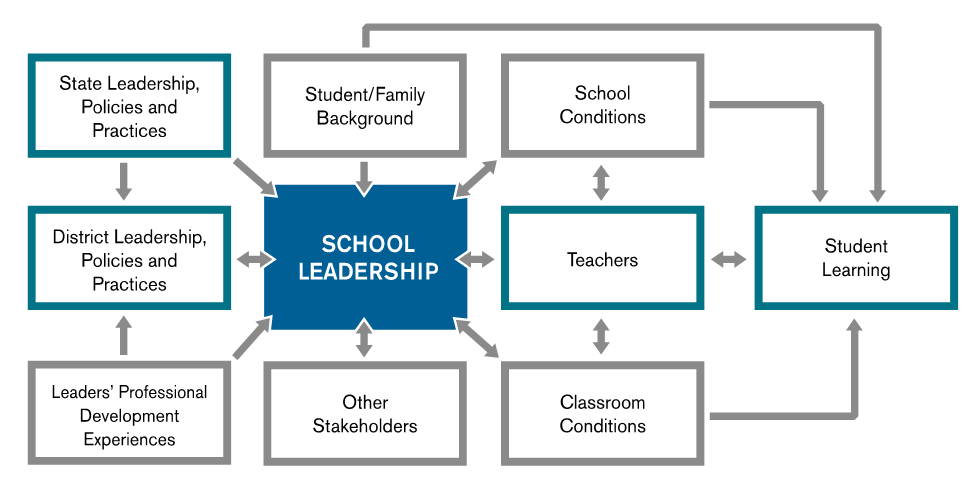

A contemporary large-scale study from the US and Canadian contexts, also including a comprehensive and systematic review of existing research (Leithwood, Louis, Anderson, & Wahlstrom, 2004), highlights the important role played by the school district as a support structure for school leaders, as illustrated in the model in figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Leadership at multiple levels

Source: Wahlstrom, Louis, Leithwood, & Anderson, 2010, p. 6.

The model in Figure 1 shows direct and indirect relationships between school district leadership, local school policies and school leadership, on the one hand, and teachers’ work and student learning on the other. The model is drawn from the final research report of the above mentioned large-scale research project of ten years duration studying the mechanism through which leadership at different governing levels interacts with teachers’ work and student learning (see Louis, Leithwood, Wahlstrom, & Anderson, 2010). One specific part of the report investigates the indirect impact of US school district’s use of performance data. The analysis showed that the use of these accountability devices had either no impact or even a slightly negative impact on classroom effectiveness. In other words, when school leaders and their teachers are targets for a “tsunami” of performance data, which is a central premise in the accountability discourse, the partial effect is zero or negative (Wahlstrom et al., 2010). The inference also concurs with a study demonstrating that Norwegian school principals found performance data as a useful tool for upwards reporting, but not for their own school improvement endeavors (Skedsmo, 2009). In contrast, when selective use of performance data co-existed with school principals’ individual

sense of self-efficacy, and the group of school principals’ sense of collective efficacy[2], the result was dramatically changed to a marginally positive effect on student learning (Wahlstrom et al., 2010). The causal argument is that self-efficacy and collective efficacy enabled school leaders to work consistently with performance data in order to accomplish educational goals through a resilient self-belief in their capabilities to exert control over actual work environments. Building on this general insight, the current review has elaborated three nested relational factors related to Nordic school district governance and leadership seen from the school principals’ perspective. First, trusting relationships with their superintendent, to which they are subordinated, paired with a trusting learning climate in municipal school leadership groups, emerge as important. Second, leadership support from the school district administration of the municipalities alongside, third, a strong municipal competence in critical educational domains seems to be of importance for this crucial link of the governance chain.

Broken chains in Nordic school governance

The school governance system found in all Nordic countries can be understood as both tightly and loosely coupled systems, especially when analyzing policy implementation across various levels (Paulsen & Høyer, 2016a). The view of education systems as tightly coupled implies a government model, in which school administrators at higher levels of the system possess control devices for schools, and the higher-ranked administrators can feel confident that school leaders and teachers will implement decisions in practice (Weick, 1982). In contrast, the conception of school systems as loosely coupled acknowledges that school governance takes place in multi-level systems that entail many broken chains (Paulsen, Johansson, Nihlfors, Moos, & Risku, 2014).

The last 20-30 years of restructuring of public sectors in the Nordic countries has led to substantial decentralization of responsibilities for efficient and effective management of financial and human resources. From the state to the municipalities and further to the schools which are governed by the school law, curriculum and local political policies. However, the state tightens other coupling mechanisms in order not to lose the necessary insight and control over public institutions. As a result, more detailed aims, standards, national tests and accountability devices are seen within the education system (Paulsen et al., 2014, pp. 815-816). On the other hand, a series of “broken chains” have been observed, denoting a gap in the formal system architecture that is sought to be filled by informal coordination and collaboration (Moos, Nihlfors, et al., 2016b). The argument follows a line of research showing that a mutually adaptive relationship between the layers in the governance system is crucial for a productive implementation of reform in schools (Datnow, 2002).

Group learning as compensation for broken chains

Sarason (1996) found two decades ago that school improvements are increased where the conscious barriers between local education authorities and schools are challenged. As noted, in their large-scale longitudinal study, Leithwood and colleagues found that successful school leader teamwork at district level supported the principals’ sense of self-efficacy, which in the next round strengthened their school development endeavors (Leithwood, Anderson, & Louis, 2012). The same study also detected that when school leaders and their superintendents develop a strong sense of efficacy as a group, through collaborative learning, school development is further strengthened (Louis et al., 2010). This line of reasoning points uniformly on collaborative group learning at the municipality level as a potential driver for school leaders’ capabilities to support and enhance school development (Moos, Kofod, & Brinkkjær, 2016).

Interpersonal trust in organizations

In interpersonal and intra-organizational settings, trust is defined as “a psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intentions or behavior of another” (Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt, & Camerer, 1998, p. 395). Trust is often measured by three characteristics of the trustee: ability, benevolence, and integrity (Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, 1995). A trusting party may have strong expectations of a positive outcome of cooperation, and may therefore have more solid basis for collaboration (Høyer & Wood, 2011). As noted, “trust is necessary for effective cooperation and communication, [which are] the foundations for cohesive and productive relationships in organizations” (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2000, p. 549). As such, trust between interdependent actors functions as a “lubricant” for productive collaboration in groups (Kahn, 1990), when people have confidence in other people’s words and deeds. In contrast, distrust can inevitably impair organizational effectiveness since it is likely to have a deleterious effect on communication: “When interacting with a distrusted person, especially a person who holds more power within an organizational hierarchy, an employee may feel compelled to be evasive or to distort attitudes or information in order to protect his or her interests” (Tschannen-Moran, 2001, p. 313).

Learning climate in groups

A trust-based school governing culture is arguably important in the relationship between the municipal school superintendent and the group of school leaders in the municipality. Specifically, when school leaders are assembled by superintendents in municipal school leadership groups, a climate of psychological safety is beneficial in terms of establishing shared understandings of how to deal with school reform implementation. Psychological safety builds on and goes beyond trust, denoting a group climate characterized by a shared belief among the members that the team is a safe zone for speaking up, identifying problems, and bringing in new perspectives, and, has been shown to be one of the strongest group-level predictors of learning in teams (Edmondson, 1999, 2004; Edmondson & Lei, 2014; Hjertø & Paulsen, 2017). Psychological safety denotes an emergent state manifest in a shared belief among the members of the team that it is a safe zone for personal risk-taking, addressing problems and speaking about personal challenges (Edmondson, 1999). When psychological safety is high, school leader group members will be confident that no one will be embarrassed, rejected, or punished by someone else in the team for offering critical viewpoints, novelties, negative performance information, or contrasting perspectives. (Edmondson, 1999). We consider this as particularly important in a school governing system, where one of the main avenues, through which superintendents can exert influence, goes through group interaction with their school leaders.

Competence held by school districts and assessed by principals

The generic concept competence encompasses knowledge, skills, and attitudes related to the work context in question (Cannon-Bowers, Tannenbaum, Salas, & Volpe, 1995). The underlying premise posits that for district leaders and local politicians to exert influence on school leaders’ priorities and action programs, a certain level of competence (at the municipality level) is required. As such, competence is an important component in a trusting relationship (Tschannen-Moran, 2001), and the focal point is the extent to which the school leaders within the municipality assess the competence possessed by the municipal school owner as sufficient. In such an asymmetric relationship as found in the hierarchical school governance line, the school leaders possess the power of definition for competence, as they “find” themselves at the interface between the municipality and the school. Moreover, competence can be found in several domains of knowledge, and it is, therefore, critical to assess this capacity across different areas, such as curriculum development, formative assessment practices, leadership development, legal issues, educational policy and so forth.

Method

Review sample

The current article is a review of prior published findings from a Nordic research project undertaken from 2009 to 2014 aiming to illuminate the processes through which national reform policies are filtered when they meet the meso-level of the municipalities. The sample of published work, on which the current article is based, is presented in table 1 below. The research project investigated school governing processes in Swedish, Norwegian, Danish and Finnish municipalities by means of joint survey instruments developed in a theory-based comparative design. The main purpose of this research project was comparisons between the national systems in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Finland. Specifically, the Nordic research team conducted a school superintendent survey in 2009, a school board survey in 2011, and a school principal survey in 2013—all of them focused on the interplay between school politicians, superintendents, and school leaders.

Table 1: The empirical grounding of the article

No | Authors | Type | Thematic focus |

1 | Paulsen, J. M. & Skedsmo, G. (2014) | Book chapter | Norwegian superintendents’ role in the national quality assurance system |

2 | Paulsen, J. M. (2014a) | Journal article | Norwegian superintendents as mediators of external control initiatives from the state |

3 | Paulsen, J. M. (2014b)

| Peer-reviewed conference paper | Norwegian school principals’ perceptions of vertical trust towards their superintendents and perceptions of municipal school owner competence |

4 | Paulsen, J. M. & Strand, M. (2014) | Book chapter | Norwegian school board members’ roles and functions in local school governing |

5 | Paulsen, J. M., Johansson, O., Nihlfors, E., Moos, L., & Risku, M. (2014). | Journal article | Synthesis of Nordic findings on superintendent leadership under governance regimes in transition in the Nordic countries |

6 | Høyer, H. C., Paulsen, J. M., Nihlfors, E., Kofod, K., Kanervio, P., & Pulkkinen, S. (2014) | Book chapter | Norwegian school board members’ perceptions of external control and professional trust |

7 | Paulsen, J. M. & Høyer, H. C. (2016a) | Book chapter | Norwegian superintendents’ role in the school governance process – seen from three different perspectives: Superintendents, school board members and school principals |

8 | Paulsen, J. M. & Høyer, H. C. (2016b) | Journal article | Synthesis of the Nordic research project with emphasis on the relationship between control and trust in Norwegian school governing. |

9 | Paulsen, J. M., Nihlfors, E., Brinkkjær, U., & Risku, M. (2016) | Book chapter | The engagements in social networks within the municipalities as carried out by superintendents, school board members and school leaders |

All Nordic questionnaires were transmitted electronically through self-managing web-survey systems, and dropout analyses were undertaken by all four research-teams, comparing the samples with the total population. The results indicate that the national samples of superintendents and school principals were fairly representative of their respective populations, whereas the school board survey in 2011 came out with a lower response rate and thereby a risk of some biases (see Moos, Nihlfors, et al., 2016a, for more detailed information).

Limitations of the review

The review must be read in light of several limitations. The survey data underpinning the published articles and book-chapters, on which this review is based, have been undertaken at different points of time, which open up for a series of shortcomings in the comparisons. Moreover, the data has been used in a merely descriptive matter in terms of first-order frequencies analysis in the Swedish, Norwegian, Danish and Finnish country reports, for the purpose of subsequent national comparisons. Evidently, multivariate statistical analysis would have detected more patterns and more robust testing, for example in the form of regression analysis and path analysis. This has not been the case in the empirical materials (from Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Finland) that underpin this current review article. A more complete Nordic presentation should also include data materials from Iceland.

Summary of findings

Interdependence between system levels

As highlighted in international reform implementation research, the relationship between the actors are crucial enabling conditions for successful implementation—understood as sustainable changes in the technical core of schooling. A trusting relationship between actors at the same level as well as across multiple levels of the national educational governance system helps implementation. As noted by Datnow,

the changing district and state policies, leadership, and agendas affected the sustainability of comprehensive school reform models in different ways, quite substantially in some cases and less so in others, depending on local conditions, experiences with reform, and capacity. (Datnow, 2002, p. 233)

Further, the extent to which the same actors adapt mutually to each other emerges as critical preconditions for systemic capacity building (Fullan & Starratt, 2009).

One critical coupling element in the implementation chain is the one between municipal superintendents, school staff and local politicians—and school leaders. As laid out in one of the Swedish publications included in this current review, when a mistrusting relationship between local school politicians and principals exists, the likelihood of successful implementation will be low (Nihlfors & Johansson, 2013). Conversely, in a dialogue-based environment, where school superintendents, politicians, and school leaders share the same sense of purpose of the reform, the likelihood of school improvement is increased (Rowan, 1990).

Superintendents act as mediating agents in a broken chain of school governance:

Our findings underscore the hypothesis of a “political vacuum” in Norwegian municipalities when it comes to local school governance evident in local curriculum development, evaluation criteria, implementation strategies, organizational innovation and learning goals. When this occurs in a situation characterized by a vague and unclear policy regime, it stimulates superintendents to fill the gaps by means of their own preferences. (Paulsen & Skedsmo, 2014, p. 48)

In consequence, through performing mediation roles as coordinators and gatekeepers,

a series of national policy initiatives have been filtered out in the superintendents’ daily dialogues with the school principals. Moreover, the national quality assurance rhetoric has been translated into softer language when the superintendents meet their school principals through discussions focused on quality issues. (Paulsen & Skedsmo, 2014, p. 48)

Shared cultural-cognitive basis

It seems fair to assume that communications between superintendents and school leaders will be easy if they share a common professional education, socialization and career path (Bjørk & Kowalski, 2005). The Nordic school superintendent is typically a professional school actor with most of their training and career path embedded in the school institution (Paulsen et al., 2014). The findings support the notion that school leadership at the municipal level is more seen as an enterprise of professional expertise, and that the generalist and managerial rhetoric of the New Public Management ideology (Christensen & Lægreid, 2002; Røvik, 1996) to a very little extent have affected the recruitment of school superintendents. In the Norwegian 2009-study, 92 % of the superintendents are educated in one or another branch of professional teacher education. When it comes to career paths, more than 8 out of 10 superintendents in the sample are recruited to their first school superintendent job from the education sector, as displayed in the table below.

Table 2: Some background items of Norwegian school superintendents

Background item |

|

|

| Frequency | Percent | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Recruited from primary education | 215 | 73,88 | |||||

Recruited from other parts of the education system | 23 | 7,90 | |||||

Teacher related professional education |

| 268 | 92,10 | ||||

Source: Paulsen & Høyer, 2011.

The pattern displayed in table 2 corresponds fairly well with similar ones reported in the Danish, Swedish and Finnish country reports. Based on the work reviewed for this article it is therefore fair to say that the superintendents share a common basis of identity with their school leaders, or ‘normative and cultural ground’ in Scott’s terminology (Scott, 2014). Collaboration and tight partnerships between superintendents and leaders should, therefore, be fairly easily set up and maintained because they share the same cultural capital (Bordieu, 1993). Inherent bindings and commitments to the normative and cultural-cognitive basis of the Nordic school institutions—as a function of their professional background—would most likely support network formation and communication (Paulsen et al., 2016).

Current school reform policy documents are infused with managerial rhetoric and have, by superintendents, effectively been translated into a traditional school development language in their daily leadership discourse with their subordinated principals (Paulsen & Høyer, 2011; Paulsen & Skedsmo, 2014). The work subjected to this review thus supports, at least to some extent, the notion that superintendents translate national and municipal policies by utilizing mediator devices such as gatekeeper functions in terms of selecting the kind of issues that are set in the agenda with school leaders (Paulsen, 2014a). Superintendents’ specialist expertise in educational domains may also be a source of influence on politicians. Support for this notion is found in the Nordic school board data that portrays the superintendent as the most influential actor in the board’s agenda setting, decision making and information acquisition processes (Moos & Paulsen, 2014).

Participative learning in municipal school leader groups

School leaders in the Nordic countries participate regularly in municipal school leader groups normally headed by the superintendent. School leaders assess this participation in a fairly positive manner in terms of learning and a supportive climate. From a theoretical stance, this group setting constitutes an important avenue for superintendents to exert leadership. This forum may be tailored in order to adapt national and municipal policy initiatives to the realities of schools, and thus a potential forum for collective sensemaking.

In the Norwegian sample, 74 % of the school leaders support the statement that “the work in the school leader group of the municipality has contributed to an increase in my leadership competence”, and 67 % felt that through the participation in the school leader group they have “gained new knowledge that is relevant for my work”. The formal network embracing the superintendent and the school leader seems to add experiential work-related knowledge to the school leaders (Paulsen, 2014b).

Learning climate as coupling mechanism

Research on group-level learning in organizations has during the last decade demonstrated a crucial effect of intra-group learning climate conceptualized by Amy C. Edmondson as psychological safety (Edmondson, 1999). At the individual level, psychological safety is defined as “feeling able to show and employ one’s self without fear of negative consequences to self-image, status, or career” (Kahn, 1990, p. 708). When psychological safety is high, members will perceive a shared confidence that nobody will be embarrassed, rejected, or punished by someone else in the team for bringing into the teamwork critical viewpoints, novelties, negative performance information or contrasting perspectives (Edmondson, 2003).

It is, as such, important that school leaders feel a supportive climate in the group, in terms of the school leader group being a “risk-free” zone for taking up difficult issues, problems, and even their own failures. These issues are measured by the Norwegian school leader’s assessment of the learning climate, as they have experienced it in the municipal school leader group. Of the Norwegian school leaders, 84 % reported that it was easy to “ask other colleagues in the school leader group about help”, and 69 % said that it was possible to bring up “tough issues and problems when we meet” in the school leader group in the municipality. For the school leader group to work as a forum of collective sensemaking, it is crucial that the school leaders feel that they incrementally learn something of value from their participation (Paulsen, 2014b; Paulsen & Høyer, 2016b).

Trust between school leaders and superintendents

An important element in a trusting relationship is the perception of integrity between the actors (Schoorman, Mayer, & Davis, 2007). For a vertical relationship to be characterized as trusting, especially in an asymmetric relationship within an organizational hierarchy, it would be necessary for the weakest part to perceive the strongest as benevolent and see them as someone with integrity. In this actual setting, a trusting relationship will then be characterized by school leaders’ strong propensity to give their superintendent full information about work-related issues even though it might damage their future career. Again, in the Norwegian sample, 89 % say that they have “no problems with informing my immediate superior about problems in my job as a school leader, even if it might harm my professional reputation”. Similar statements on vertical trust score very highly (Paulsen, 2014b; Paulsen & Høyer, 2016b). This pattern is fairly representative of the images reported in the Swedish and Finnish country reports. In the Danish country report, a more fine-graded pattern is reported: School leader groups are assessed as important for coordination and decision-making, whereas school leaders and their superintendents use informal one-to-one communication for supervision and coaching in pedagogical and strategic issues. Then the superintendent acts more as a coach, mentor, and sparring partner (Moos, Kofod, et al., 2016).

An element of mistrust between school politicians and school leaders?

Using the example of Sweden, school board members indicated a low level of trust in the capacity of school principals to lead school development, and they also assessed the school principals’ competence as mediocre (Nihlfors & Johansson, 2013, p. 6). On the other hand, the school principals showed strong loyalty to the state in governing Swedish schools and felt it was fair for the state to increasingly bypass the municipalities in school governing (Johansson, Nihlfors, & Steen, 2014). The Norwegian school board data displays a tendency towards low levels of trust regarding school leader capacity and loyalty in important domains. For example, only 32 % of the members in the Norwegian school boards saw their school principals as “fairly good in leading school development”. When the board members were asked to express their perceptions of school principal loyalty (with conflicting interests about student learning), only 41 % of the board members trusted that “their school principals would side with the interests of the students” (Høyer et al., 2014; Paulsen & Strand, 2014). Whereas our review indicates a trusting relationship between school leaders and their superintendents, this inference is significantly modified towards distrust when it comes to the mutual relationship between school leaders and school politicians, as most evidently displayed in the Swedish material (Johansson, Nihlfors, Steen, & Karlsson, 2016).

Leadership support

From a general point of view, authentic and supporting leadership practices is a hallmark of a trusting relationship between two levels in a hierarchy of authority (Avolio, Gardner, Walumbwa, Luthans, & May, 2004). Moreover, individual support is a cornerstone of effective leadership as found in many different educational systems (Leithwood, 2008; Levin & Fullan, 2008). The school leaders, therefore, assessed the general leadership support from their school office in a series of critical domains, such as school development endeavors, supervision, and involvement in school development at the municipality level. In the Norwegian case, 64 % of the school principals stated that “the quality work of their municipality helps them in school development”, whereas 58 % stated that “the supervision and follow-up activities by the school administration are supportive of school development”. When asked explicitly about the value of “the work with the yearly quality report”, only 40 % assess it positively, which indicates large variation among Norwegian municipalities (Paulsen, 2014b).

School owner’s competence in critical domains

School leaders assessed the general competence of the school office and their school owner as variable and partly mediocre in a range of important domains, such as legal issues, leadership development, and curriculum development. The school leaders seem more satisfied with the support they received in leadership. It is noteworthy that the majority do not perceive work with the municipal quality report, a compulsory yearly routine in the National Quality Assurance System (NQAS), as very useful. Turning to the school leaders’ assessments of competence (in critical domains) in the municipality administration to which they are subordinated: Only 56 % of the Norwegian sample assessed the competence of their municipality as satisfying in “educational policies”, which must be regarded as a rather mediocre score, taking into account the central role municipalities are given in the Norwegian school governing chain. In a similar vein, 55 % of the school principals in the sample assessed their municipality as competent in “legal issues”, which is surprisingly low (Paulsen, 2014b).

Motivational drivers of superintendents

The Nordic superintendent survey portrays a sense of meaningfulness in the job, paired with a self-belief of efficacy related to mastering the tasks—even if the workload increases further (Johansson, Moos, Nihlfors, Paulsen, & Risku, 2011). Superintendents also feel high self-efficacy in schools and with principals, which is supported by the fact that they share the same cultural capital in terms of professional knowledge, documented in the background of superintendents as educationalists. Nordic superintendents’ main motivation clusters around a sense of self-efficacy in perceiving their work as meaningful and important for the municipal school owner, and around self-belief in their own capacity to develop school leaders in a positive direction (Johansson et al., 2011). Superintendents see themselves mainly as implementation and change agents for schools and school leaders (Nihlfors, Johansson, Moos, Paulsen, & Risku, 2013).

The Norwegian superintendents were in 2009 asked about the motivational elements of their work, and the answers clustered around a fairly strong sense of self-efficacy, manifesting, for example, in 96 % from the Norwegian sample reporting explicitly that they see their work as meaningful and 96 % that they see the superintendent as “important for the municipality’s role as school owner”. Further, 79 % of the superintendents perceive that they can “develop school leaders in a positive direction”. In a similar vein, 93 % hold that they can exert influence on primary education within their municipality. The superintendents evidently see themselves as influential agents of change and development in the governance of schools (Paulsen & Høyer, 2011).

Discussion

The review of the research project analysing Nordic municipalities’ capacity as school owners, has focused on the relationship within the municipal school governance system, manifested most evidently by a school superintendent and his or her staff, and the next chain in the governing line the school principals. The starting point is the observation that throughout the Nordic countries, school governance plays out in a line of hierarchical authority with broken lines or loose couplings (Moos, Nihlfors, et al., 2016a), in line with research on educational reform implementation (Datnow, 2002; Hargreaves & Goodson, 2006). A synthesis of our review suggests six important avenues, through which municipal school owners can exert positive influence on school capacity building: 1) building professional learning teams of school principals (within the context of the municipality organization); 2) ensuring a supportive group-climate in the same context, characterized by psychological safety, so that school leaders can speak up; 3) a trusting interpersonal relationship to the superintendent as reference-point; 4) paired with leadership support; 5) educational competence in the municipal apparatus; and finally 6) reducing mistrust between local school politicians and school professionals.

Implications for conceptual development and further research

Our first implication suggests further research and conceptual development of the learning environment in which school superintendents and school leaders play out their regular interactions. Large-scale studies point to the importance of strengthening the school leaders’ sense of efficacy in their leadership endeavors through learning and professional development at the school district level (Louis, 2015), and our review follows this line of argument by drawing attention to group learning conditions. Since this current review is based on descriptive data in country-reports conducted solely for comparative purposes, we recommend studying group-efficacy, trust, safety and learning motivations in multilevel statistical analysis as demonstrated in a more recent publication (Hjertø & Paulsen, 2017). Additionally, qualitative in-depth action-research of the specific learning processes taking place in professional dialogue forums could add complementary insight beyond what can be harvested from cross-sectional statistical studies.

Implication for superintendent leadership practice

The study recommends school superintendents in Norwegian municipalities to focus effort on developing their school leader teams. Specifically, a sustainable learning climate characterized by psychological safety and openness for ideas is crucial for mutual adaptation between the school owner and the group of school principals that work in the crossfire of conflicting demands and expectations related to school improvement and reform implementation. A bulk of prior research reveals that a supportive and coaching leadership style promotes psychological safety in groups alongside a trusting and authentic behavior (e.g. Edmondson, 1999; Garvin, Edmondson, & Gino, 2008). Specifically, the different ways through which superintendents react to negative performance feedback (related to educational achievements) is crucial (Sutton, 2010). As clearly demonstrated in the large-scale investigation undertaken by Karen Seashore Louis and colleagues for the Wallace Foundation, the development of self-efficacy and group-efficacy among the principals will support their endeavors of using the performance feedback inherent in the data sets to support improvement practices (Louis et al., 2010). Also as demonstrated in other studies, self-efficacy and group-efficacy are stimulated by a climate of psychological safety (Gully et al., 2002).

Implication for local school politics

The results from the review presented above indicate that the municipalities’ work with the quality report is only a weak and insufficient driver for school development efforts. The findings rather support the notion that quality reporting and assurance practices are primary vehicles for external control and reporting within the hierarchical governing system, yet only infrequently coupled with the school development work—concurrent with prior large-scale research from the Norwegian context. Rather local school politicians should put effort in capacity building and competence development in the municipality staff paired with a team-based in-service strategy for school principal development. There is also a need for developing a shared understanding and sense of purpose among local school politicians and school leaders.

References

Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Walumbwa, F. O., Luthans, F., & May, D. R. (2004). Unlocking the mask: A look at the process by which authentic leaders impact follower attitudes and behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(6), 801-823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2004.09.003

Bjørk, L., & Kowalski, T. J. (2005). The contemporary superintendent: Preparation, practice and development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Bordieu, P. (1993). Sociology in question. London: Sage.

Cannon-Bowers, J. A., Tannenbaum, S. I., Salas, E., & Volpe, C. E. (1995). Defining competencies and establishing team training requirements. In R. A. Guzzo & E. Salas (Eds.), Team effectiveness and decision making in organizations (pp. 333-380). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Christensen, T., & Lægreid, P. (2002). Reformer og lederskap: Omstilling i den utøvende makt (Reforms and leadership: Change in the governing power). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Datnow, A. (2002). Can we transplant educational reform, and does it last? Journal of Educational Change, 3(3-4), 215-239. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021221627854

Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350-383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

Edmondson, A. C. (2003). Speaking up in the operating room: How team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1419-1452. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00386

Edmondson, A. C. (2004). Psychological safety, trust and learning in organizations: A group-level lens. In R. Kramer & K. Cook (Eds.), Trust and distrust across organizational contexts: Dilemmas and approaches (pp. 239-272). New York: Sage.

Edmondson, A. C., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 23-43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305

Fullan, M., & Starratt, L. (2009). Sustaining leadership in complex times: An individual and system solution. In M. Fullan (Ed.), The challenge of change. Start school improvement now! (pp. 157-178). Thousand Oaks: Corwin.

Garvin, D. A., Edmondson, A. C., & Gino, F. (2008). Is yours a learning organization? Harvard Business Review, 86(3), 109-116.

Gully, S. M., Incalcaterra, K. A., Joshi, A., & Beaubien, J. M. (2002). A meta-analysis of team-efficacy, potency, and performance: Interdependence and level of analysis as moderators of observed relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(5), 819-832. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.5.819

Hargreaves, A., & Goodson, I. (2006). Educational change over time? The sustainability and nonsustainability of three decades of secondary school change and continuity. Educational Administration Quarterly, 42(1), 3-41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X05277975

Hjertø, K. B., & Paulsen, J. M. (2017). Learning outcomes in leadership teams: The multi-level dynamics of mastery goal orientation, team psychological safety, and team potency. Human Performance, 30(1), 38-56. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2016.1250765

Høyer, H. C., Paulsen, J. M., Nihlfors, E., Kofod, K., Kanervio, P., & Pulkkinen, S. (2014). Control and Trust in Local School Governance. In L. Moos & J. M. Paulsen (Eds.), School Boards in the Governance Process (pp. 101-115). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05494-0_7

Høyer, H. C., & Wood, E. (2011). Trust and control: Public administration and risk society. International Journal of Learning and Change, 5(2), 178-188. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJLC.2011.044209

Johansson, O., Moos, L., Nihlfors, E., Paulsen, J. M., & Risku, M. (2011). The Nordic Superintendents’ Leadership Roles: Cross-National Comparisons. In J. Mc Beath & T. Townsend (Eds.), International Handbook on Leadership for Learning (pp. 695-725). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1350-5_30

Johansson, O., Nihlfors, E., & Steen, L. J. (2014). School Boards in Sweden. In L. Moos & J. M. Paulsen (Eds.), School Boards in the Governance Process (pp. 6). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05494-0_5

Johansson, O., Nihlfors, E., Steen, L. J., & Karlsson, S. (2016). Superintendents in Sweden: Structures, cultural relations and leadership. In L. Moos, E. Nihlfors & J. M. Paulsen (Eds.), Nordic Superintendents: Agents in a broken chain (pp. 207-232). Dordrecht: Springer.

Kahn, W. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692-724. https://doi.org/10.2307/256287

Lee, M., Louis, K. S., & Anderson, S. (2012). Local education authorities and student learning: The effects of policies and practices. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 23(2), 123-138. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2011.652125

Leithwood, K. (2000). Understanding schools as intelligent systems. Greenwich CT: JAI Press.

Leithwood, K. (2008). Characteristics of high performing school districts. A review of empirical evidence. Toronto: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE).

Leithwood, K., Anderson, S. E., & Louis, K. S. (2012). Principal efficacy: District-lead professional development. In K. Leithwood & K. S. Louis (Eds.), Linking leadership to student learning (pp. 119-141). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Leithwood, K., & Louis, K. S. (1998). Organizational learning in schools. Contexts of learning. Lisse: Swets and Zeitlinger Publishers.

Leithwood, K., Louis, K. S., Anderson, S., & Wahlstrom, K. (2004). Review of research: How leadership influences student learning. http://www.wallacefoundation.org

Levin, B., & Fullan, M. (2008). Learning about system renewal. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 36(2), 289-303. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143207087778

Louis, K. S. (2015). Linking leadership to learning: State, district and local effects. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 2015(3), 30321. https://doi.org/10.3402/nstep.v1.30321

Louis, K. S., Leithwood, K., Wahlstrom, K., & Anderson, S. A. (2010). Investigating the links to improved student learning. Final report of research findings. Toronto: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE).

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709-734.

Moos, L., Kofod, K., & Brinkkjær, U. (2016). Danish superintendents are players in multiple networks. In L. Moos, E. Nihlfors & J. M. Paulsen (Eds.), Nordic superintendents: Agents in a broken chain (pp. 207-232). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25106-6_2

Moos, L., Nihlfors, E., & Paulsen, J. M. (2016a). Directions for our investigation of the chain of governance and the agents. In L. Moos, E. Nihlfors & J. M. Paulsen (Eds.), Nordic Superintendents: Agents in a broken chain (pp. 1-24). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25106-6_1

Moos, L., Nihlfors, E., & Paulsen, J. M. (2016b). Tendencies and trends. In L. Moos, E. Nihlfors & J. M. Paulsen (Eds.), Nordic Superintendents: Agents in a broken chain (pp. 311-334). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25106-6_11

Moos, L., & Paulsen, J. M. (2014). School Boards in the Governance Process. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05494-0

Nihlfors, E., & Johansson, O. (2013). Rektor – en stark länk i styrningen av skolan (The school principal – a strong linkage in school governing). Stockholm: SNS Förlag.

Nihlfors, E., Johansson, O., Moos, L., Paulsen, J. M., & Risku, M. (2013). The Nordic superintendents´ leadership roles: Cross-national comparison. In L. Moos (Ed.), Transnational influences on values and practices in Nordic educational leadership. Is there a Nordic model? (pp. 193-212). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6226-8_12

Paulsen, J. M. (2014a). Norwegian superintendents as mediators of change initiatives. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 13(4), 407-423. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2014.945654

Paulsen, J. M. (2014b). School principals’ perceptions of school ownership capacity. Paper presented at the Educational Leadership in Transition – the Global Perspectives, Uppsala University, Uppsala.

Paulsen, J. M., & Høyer, H. C. (2011). Superintendent leadership in Norwegian municipalities. Country report: Norway. Rena: Hedmark University College.

Paulsen, J. M., & Høyer, H. C. (2016a). External control and professional trust in Norwegian school governing: Synthesis from a Nordic research project. Nordic Studies in Education, 36(2), 86-102. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1891-5949-2016-02-02

Paulsen, J. M., & Høyer, H. C. (2016b). Norwegian superintendents are mediators in the governance Chain. In L. Moos, E. Nihlfors & J. M. Paulsen (Eds.), Nordic Superintendents: Agents in a broken chain (pp. 99-138). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25106-6_4

Paulsen, J. M., Johansson, O., Nihlfors, E., Moos, L., & Risku, M. (2014). Superintendent leadership under shifting governance regimes. International Journal of Educational Management, 28(7), 812-822. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-07-2013-0103

Paulsen, J. M., & Moos, L. (2014). Globalisation and Europeanisation of Nordic Governance. In L. Moos & J. M. Paulsen (Eds.), School Boards in the Governance Process (pp. 165-178). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05494-0_11

Paulsen, J. M., Nihlfors, E., Brinkkjær, U., & Risku, M. (2016). Superintendent leadership in hierarchy and network. In L. Moos, E. Nihlfors & J. M. Paulsen (Eds.), Nordic Superintendents: Agents in a broken chain (pp. 207-232). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25106-6_7

Paulsen, J. M., & Skedsmo, G. (2014). Mediating tensions between state control, local autonomy and professional trust. Norwegian school district leadership in practice. In A. Nir (Ed.), The educational superintendent: Between trust and regulation: An international perspective (pp. 39-54). New York: Lambert Academic Publishing.

Paulsen, J. M., & Strand, M. (2014). School Boards in Norway. In L. Moos & J. M. Paulsen (Eds.), School Boards in the Governance Process (pp. 49-65). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05494-0_4

Rhodes, R. A. W. (1997). Understanding governance: Policy networks, governance, reflexivity and accountability. Milton Keynes: Open Univesity Press.

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 393-404. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1998.926617

Rowan, B. (1990). Commitment and control: Alternative strategies for the organizational design of schools. Review of Research in Education, 16, 353-389. https://doi.org/10.2307/1167356

Røvik, K. A. (1996). Deinstitutionalization and the logic of fashion. In B. Czarniawska & G. Sevón (Eds.), Translating organizational change (pp. 139-172). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Sarason, S. (1996). Revisiting “The culture of the school and the problem of change”. New York: Teachers College Press.

Schoorman, F. D., Mayer, R. C., & Davis, J. H. (2007). An integrative model of organizational trust: Past, present, and future. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 344-354. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2007.24348410

Scott, W. R. (2014). Institutions and organizations. ideas, interests, and identities. Los Angeles: Sage.

Skedsmo, G. (2009). School governing in transition? Perspectives, purposes and perceptions of evaluation policy. (Doctoral dissertation), University of Oslo, Oslo.

Stoll, L., & Temperley, J. (2009). Creative leadership teams: Capacity building and succession planning. Management in Education, 23(1), 12-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020608099077

Sutton, R. I. (2010). Good boss, bad boss. How to be the best and learn from the worst. London: Piatkus.

Tschannen-Moran, M. (2001). Collaboration and the need for trust. Journal of Educational Administration, 39(4), 308-331. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000005493

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, W. K. (2000). A multidisciplinary analysis of the nature, meaning, and measurement of trust. Review of Educational Research, 70(4), 547-593. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543070004547

Wahlstrom, K., Louis, K. S., Leithwood, K., & Anderson, S. E. (2010). Investigating the Links to Improved Student Learning. Executive Summary of Research Findings. Minnesota: University of Minnesota.

Wood, R., & Bandura, A. (1989). A social cognitive theory of organization management. Academy of Management Review, 14(3), 361-384.