NJCIE 2018, Vol. 2(1), 39-54

http://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.2238

Kindergarten Practice: The Situated Socialization of Minority Parents

Janne Solberg[1]

Associate

Professor, University of South-Eastern Norway

Peer-reviewed article; received 30 October 2017;

accepted 23 April 2018

Abstract

Almost all parents in Norway

use kindergarten and part of becoming a kindergarten

parent is learning the routines of the particular institution. Thus, kindergarten

parents go through a socialization process, learning amongst other how to

deliver and pick up their children. Building on ten days observations of

bringing and delivery scenes in a kindergarten, it is here suggested that this

socialization process may have a racialized character. The kindergarten in

question had special delivery routines, which the kindergarten staff expected

parents to carry out, but not everybody did, and the article investigates how

the staff reacted towards the three deviant cases observed. The bottom-up

analysis of the social interaction between the parents and the staff is here supplied

by the perspective of racialization, questioning the gaze of majority persons

and their naturalized power to define non-complying parents as something other. The kindergarten staff did not

overtly orient to the non-compliance as a problem in the case where the parent

had a majority background, which was in much contrast to their conduct in the

two other cases with minority parents. In these cases, the staff interacted

in a unilateral manner by giving advice and even instructions, very much

embodying what Palludan in her study of children-staff interaction calls the teaching tone.

Keywords: kindergarten parents;

minority parents; parent socialization; institutional discrimination; othering

Introduction

In Norway, all children from about the age of one year, are entitled to

a place in kindergarten providing children

with good opportunities for development

and activity. In 2016, 91% of children between one to five years old attended kindergarten,

for children speaking a minority language the number was 76%[2]

(SSB, 2017). The kindergarten service is mainly

financed by public grants, being disposed of

by the municipal. There is a user fee as well, but the size of the fee is

regulated and there are arrangements ensuring reduced payment for low-income

families. This means that attending kindergarten

is a very ordinary thing to do in everyday family life, and in the kindergarten, they meet staff with different

backgrounds in terms of education. About 40% have a pedagogical education (mostly as preschool teachers), about 30% are

skilled workers (often children and youth workers) and the rest are registered

with “different backgrounds” (Utdanningsdirektoratet,

2018).

According to The Kindergarten Act §1, the

relationship between kindergarten staff and parents should be characterized by

cooperation and mutual understanding. While these terms suggest an equal partnership between parents and staff, the kindergarten

is also an institution with “predefined patterns of conduct” (Berger & Luckmann, 1967, p. 72) which parents are expected to adapt to. Thus, in everyday

encounters, parents and kindergarten staff meet as insiders and outsiders, rather than on neutral ground as equal partners

as policy documents seem to assume. Building on observations of delivery/picking-up

episodes for a period of ten days, the analytic focus in this article is on how

the staff in this kindergarten socialize parents to the local routines for

delivering children. The so-called

kitchen-routine will be described in more detail below, but in short, parents

were expected to deliver their children in a common area called the kitchen, rather than in the wardrobe

area. The special

arrangement had been explained to the parents in a parent meeting, I was told,

but not all parents attended the meeting, and as one of the preschool teachers said: “This routine is perhaps not so easy to

understand for all [parents]”.

The present article

investigates the local norms for delivering children, with a special focus on

how the kindergarten staff managed deviances from the expected routine. Though

it is more usual to adopt the term socialization in the child-adult

relationship, it will here be argued that this is an inherent dimension of the

parent-staff relationship as well. This is not to suggest a unilateral

understanding of socialization as this article is grounded in the micro-perspective of

ethnomethodology. Within this perspective, conversation or talk is “the central

medium for human socialization” (Goodwin &

Heritage, 1990, p. 289) and the capacity to socialize

others relates to the performance of all participants

or members of a group—not primarily those conventionally

acknowledged as socialization agents or professionals. As expressed in the

research of language socialization: “(…) it is not only the child who is being socialized—the child, through its actions and verbalizations, is also actively (if

not necessarily consciously) socializing the mother as a mother” (Kulick &

Schieffelin, 2008, p. 350). Accordingly, socialization is not

a one-way street and in the analysis section, there will be an instance

demonstrating that also parents at times may attempt to change the conduct of

the staff.

The staff’s socialization-in-action described in

this article takes place in a nursery department

where over half of the parents had a minority

background. In this article, I will often refer to persons with majority

or minority background. The content of these terms are debated, but it is common

to understand a minority group to be non-dominant and numerically inferior to the

rest of the population of a state (Døving, 2011).

The

socialization practices observed will be discussed in terms of being

discriminatory towards minority parents, and if so, at what analytic level does

the discrimination seem to be (systemic vs. individual discrimination). In

terms of analysis, this means looking at the practices from both an emic

(from inside) and an etic (from

outside) viewpoint (Pike, 1967). Following an ethnomethodological emic approach, it is perhaps hard

to argue that it was a member’s project to discriminate or racialize. Instead, racialization is nowadays more often

thought of as taken for granted understandings and language practices

unconsciously shared by the majority group. Within the post-colonial tradition,

building on Edward W. Said’s book Orientalism

(1974), members of the West, or the majority, have the power to define what is

not normal or different about them (See Rogstad

& Midtbøen, 2009). But while it is acknowledged that everyday

language is an efficient tool for minorizing

or othering minority groups, there is little empirical research

documenting the connection between discriminating structures and individual

actions (Rogstad &

Midtbøen, 2010). This article will contribute in

this respect, and, as the analysis will show the everyday categorization

between us and them may in practice be very subtly performed, invoking

categorizations and descriptions indexing the heart of the institutional logic,

rather than ethnicity per se.

Previous research

The socialization

of kindergarten parents is at least

implicitly touched on in research on the Nordic kindergarten tradition.

Findings from the Norwegian survey study “The multicultural kindergarten in

rural areas” suggest that the staff do expect parents to adapt to institutional

routines. As much as 70% of the staff agreed on

the importance of parents adapting to the rules of the

kindergarten as quickly as possible (Andersen et al., 2011). But adapting to the rules of the kindergarten can be a tall order

to some parents, especially in the start-up period, and even more, if the parents have a minority background

(Andenæs, 2011; Bundgaard & Gulløv, 2008). In the interview study of Andenæs (2011) an immigrant mother explains that

she finds delivering and picking up at day care

difficult:

Being an immigrant implies that one is constantly evaluated by others she says, to see whether one is good enough or not. She feels a need to protect herself from the kind of interpretations she encounters, so often in the style of `it`s because you are from X country that you behave like this (Andenæs, 2011, p. 61)

The ethnography study of Bundgaard and Gulløv (2008) describes a difficult situation

from the start-up period where a minority mother stayed in the wardrobe area

and refused to enter the nursery department, with much difficulty for the

start-up. The most interesting about this instance is how passive the kindergarten

staff act.

Possibly, the staff’s passivity described in

Bundgaard and Gulløv (2008) should be understood as

business-as-usual, rather than representing something very unusual in the kindergarten

institution. In a recent Norwegian master thesis observing the interaction

between staff, parents and children, Haug (2016) argues,

by adopting Latour’s concept of internalized

borders, that there is an invisible line between the department (as the

staff’s area) and the wardrobe area. Merely in two of forty-two observed

situations in the morning, the parent would cross the border and follow the

child into the department. Although the caretakers in Haug’s study did say that they wanted the parents to

enter the department more often, little was actually done to promote this. The

thesis also gives examples of how parents who do cross the line are not spoken

to (Haug, 2016, p.

33). Hence, if the staff does not relate to parents who are crossing the

border as doing the right thing it is

perhaps not only minority parents who will experience the wardrobe area as a

more neutral space (Bundgaard &

Gulløv, 2008, p. 60). Much likely, parents who are

unfamiliar with the Nordic kindergarten

tradition may be even more likely to feel out

of place when crossing the border.

Moreover, research also gives reason to investigate whether

parents with minority background are met in a different way compared to

majority parents. Palludan’s ethnographic study (Palludan, 2005), building on

Bourdieu’s theoretical framework (Bourdieu, 1977), describes how the staff meets children from different social and ethnic

groups with what she calls different language

tones (Palludan, 2005,

2007). She describes a communication

pattern where children with majority background are met with a democratic exchange tone while children with

minority background are met with a teaching

tone, unilaterally instructing and showing the child how to perform. This

means that not all children are in a position

to establish an equal partnership with the kindergarten staff. According to

Palludan (2005, p. 138), this segregated recognition

practice is also at work when the staff interact

with the parents, but evidence demonstrating how this comes about in practice

is not presented. However, as we will learn from the data presented in this

paper, this may not be an unreasonable claim.

Context of the study: The routine

Due to economic reasons, only one of the four departments would be

staffed before 8.30 a.m., in the three other departments,

the children should be delivered in the

kitchen. This meant that children quite often would be greeted by care

providers who they did not know very well. Delivering a child in the kitchen may be seen as fulfilling what

could be called a trajectory of care, which might be more or less elaborated.

Before entering the kitchen, the parents need to help their child with undressing and

then look over the child’s shelf in the wardrobe. When the parents approach the kitchen, they encounter an open area with

many tables, the number of persons in the room (adults and children sitting at

the tables) may vary from day to day. No

doubt, this is a very different material structure compared to the more usual

pattern described in Haug (2016, p. 24) where the care provider meets the child and the parent in the wardrobe

area. The material structure of the kitchen sets premises for the conduct of

both parties, thus the structure so to speak becomes a “co-creator in and of

everyday life” (Dannesboe, 2017, s 215). While the notion kitchen assumes familiar users, there was a divide between the

children who would have breakfast in the

kitchen and those who would not.

When the child was having breakfast, the

parents had a clear mission in the room: To place the child at one of the

tables, open the lunch-box, pour up milk and say goodbye to the child. In

practice, this could be rather time

extensive, especially in the case of toddlers. One mother used to take off both

her jacket and her shoes before following her child into the kitchen. Both kindergarten

staff and parents expected children of all ages to choose a table and then a

chair on their own by asking them “Where do you want to sit?” Usually there was

not very much talk between the parents and the staff as the latter tend to

concentrate upon giving the child a good reception, however, greetings as “good morning” and “goodbye”, with or without

eye contact, were common. There could be exceptions to this child-centered focus, for instance, if the child had been, or could

possibly be, ill. This represents an out-of-order

state where parents and staff talk together within an adult frame. Although in

an ethnomethodological perspective all actions are accomplishments, parents who accompany a child eating breakfast did

not seem to have much trouble with making themselves accountable in this

setting. Their actions so to speak fulfills

the purpose of the room, the furniture (table, chairs) and the equipment onto

the table (glasses, water jug, a carton

of milk and so forth).

In contrast, the parents whose children had

eaten breakfast at home were obviously in a more ambiguous social situation.

These children should also be brought into the kitchen, but then they should be

channeled into the one department which

had the early guard (this would ambulate according to an internal schedule, not

communicated to the parents). Parents of children who had eaten breakfast at

home would often stop at the doorstep or take just a few steps into the kitchen

to make themselves visible to the staff. Usually,

there was not much interaction with the staff, apart from greetings and/or eye

contact. From my position, I could

observe that eye contact was not always very easy to establish, for instance,

when the staff was sitting with the back

to the doorway. The staff were often busy

talking with the children and did not seem to monitor the doorways. When eye

contact (eventually) was established the staff would usually not rise from the

chair and approach the parent in the doorway. Messages were seldom given to the

staff, but at one occasion a father informed, standing in the doorway, that the

child “had been to the toilet this morning” (I guess this had been an issue to

the child in question). Providing such private information about a child with

the whole room as overhearers appeared to be somewhat odd. But this parent so

to speak ignored the poor terms of talking, given this particular material

structure, and provided the information he thought was important.

A very important stage of delivering

in the kitchen was saying goodbye to the child. This is part of the intimacy practice (Haug, 2016, p. 29)

between parent and child and implies physical contact (hugs, kisses, bowing and

so forth) in addition to verbal interaction (Bye honey, have a nice day). As

families nowadays are defined by the quality of the relationship, rather than a

given membership (Finch, 2007, p 71), the goodbye exchange was obviously not

simply an empty ritual, but a moment of much importance to the parents. This

became explicit in scenes where the child for

some other reason did not cooperate and turned away from the parent. In one

example a mother explained her child’s dismissive behavior with that the child might not feel all well this morning,

thus she obviously interpreted this as deviant conduct, calling for an account

to the audience. In another instance, an older child would not return to the mother

in the doorway to kiss her goodbye, and the mother sighed heavily on her way

out, with a sorrow expression on her face (this happened several times during

the observation period). Thus, dropping-off in the kitchen involved a composed

trajectory of care where good family relations were displayed to a wide

audience (the staff, other parents/children).

Methods

The aim of the fieldwork was to gain empirical knowledge about the

informal parent cooperation in everyday encounters, with a special focus on the

staff’s interaction with parents who had a minority background. The study was

funded by Oslofjordfondet and The University College of Southeast Norway. The observations

were made over a fortnight period and summed up to about sixteen observation

sessions, lasting at least two hours each. The parents received information

about the study in a parent meeting before start-up and written information

about the study was provided as well. Parents could opt out of being observed,

but no one did. In the morning, I did my observations sitting on a chair in the

kitchen or from the bench in the wardrobe area in one of the departments. The

children and the parents entered the kitchen from four doors, and sitting on a

chair in the middle of the room, I was able to monitor the doorways, in both

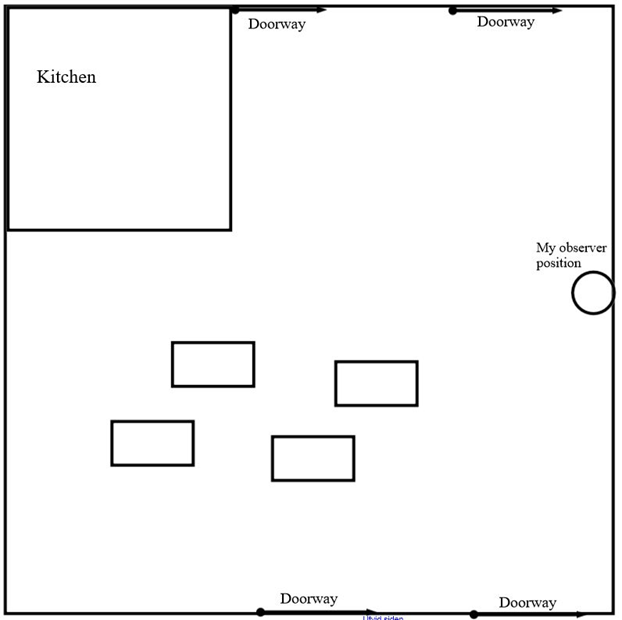

directions. The next page shows a simple sketch of the room.

Figure 1: The

kitchen

The parents would enter the room from the wardrobe area through the four

doorways, while the staff would sit around at the tables and talk with the

children or they would go to and from the tables and the kitchen section. As I

will come back to in the analysis section, sitting in the middle of the room

gave me a wider perspective than the staff who could sit with their back to

some of the doors. In terms of research roles,

I was certainly more an outsider than an insider. Being interested in the

interaction between the staff and the parents I was not interested in going

native as a staff member, but at times it was difficult to be an observer only.

Mainly because of the children who often talked to me or approached me, to sit on my lap or to give me a hug.

Sitting in these areas, without nothing else to do, I also established a polite

relation to the parents, mostly through smiles and greetings. Often I was the

only adult person available, as the staff were elsewhere or occupied with the

kids, thus to me, it felt like an

appropriate thing to do.

Building on an ethnomethodological perspective,

the expression unmotivated looking (Psathas, 1995,

p. 45), suggests the researcher to start

observing without theoretical assumptions and thus be interested in whatever is

going on in self-organizing settings. Although I sympathize with the empiricist image of ethnomethodology, my lens

would, of course, be affected by my prior knowledge about kindergarten practices, and, not least, earlier

research. As mentioned, Palludan’s distinction between teaching tone and

exchange tone in interaction between kindergarten staff and children (Palludan, 2005), had made me wonder whether we

could see this pattern in interaction with parents as well, and in this sense

my observations may not have been all unmotivated. Though this was not

formulated as a hypothesis for the study, I was interested in learning whether

the parent’s ethnicity (as a majority/minority member) would somehow affect the

staff-parent interaction.

In ethnomethodological research, the participants’ reaction to deviant conduct is one

important resource for explicating the rules of a setting. As put by Wooofitt:

“...if someone displays that they are ‘noticing’ the absence of a certain type

of turn from a co-participant, then that demonstrates their own orientation to

the normative expectation that it should have been produced”(Wooffitt, 2005,

p. 61). This was the insight of

Garfinkel’s famous breaching experiments

where Garfinkel told his students to produce out-of-place responses in their

daily interaction (Garfinkel,

1967). The hostile reactions of the

victims displayed the normative expectation that they should have been

understood as having produced an accountable

action. The deviant conduct made the normative pattern of business-as-usual

visible. In this study, I observed that

most parents followed their child into the kitchen. Though, because a few

parents did not, it took a couple of days to firmly establish my understanding.

The routine had not been explained to me in detail, thus in the onset, I was not sure how things worked, and

because of this, I think I was able to relate the insecurity of some of the

parents in terms of what to do. My reflexivity, and possibly the parents’

reflexivity, would center around issues

such as: How far should one go into the room? Should

you talk to the staff? What do you do

when the staff does not respond or is out of the room? After having noticed a

couple of deviances to the usual pattern, I tested out my own assumptions by

asking one of the staff whether parents were supposed to follow their children

into the kitchen, and this was confirmed.

Getting the (minority)

parents into the kitchen

While most of the parents carried out the routine and accompanied their

child into the kitchen or at least to the doorstep of the kitchen, there were,

as mentioned, interesting deviances to this delivery pattern. In three cases, I

observed the parents leaving their children in the wardrobe area without

establishing contact with the staff before leaving. In the following, I will

describe how the kindergarten staff followed up each of these cases.

Case 1

The first case was a child about four

years old, in contrast to Case 2 and Case 3 this child was not a

newcomer. Her father, who had a majority background, always left the

kindergarten in a hurry. If no one from the staff was around in the wardrobe

area while he was there, he would say goodbye to the child and leave. I did not

see anybody of the staff noticing or acting on this conduct as problematic.

Case 2

In contrast to Case 1, a mother with minority background was followed up

for not bringing her child into the kitchen. I observed her as she helped her

child with getting undressed. The care provider on duty came out in the

wardrobe area and declared in a loud and clear voice (in Norwegian) “We are in the

kitchen now”, then the topic shifted to talk about today’s events. This

underlining of locality is a very indirect way of affecting the mother’s behavior, leaving it to the mother herself to

figure out that she should accompany her child into the kitchen. But the mother

was not given the chance to demonstrate her understanding of this hidden

message. The next day, another member of the staff was on duty, and she came

out in the wardrobe area and told the mother: “Very nice if you can follow him

into the kitchen”. The mother nodded and confirmed verbally in a low voice.

Compared to the day before this strategy is a more direct way of unilaterally

advising the mother which is in line with what Palludan (2005) calls the teaching tone.

Case 3

The teaching tone was even more clearly present in the third instance

where the kindergarten teacher spoke

English with a father (English is not their mother tongue, but both of them

spoke English quite well I was told). When the father came to pick up his

toddler, the teacher instantly sat down next to him on the bench in the

wardrobe area and she told him in English: “In the morning, it’s important that

you go- Sometimes there are not any

grown-ups here, so you have to bring him into ‘kjøkkenet’ [the kitchen]”. The

father said “OK”, and the kindergarten teacher said “very good”. She then

laughed briefly, stood up and left. Note that the care provider first designed

her turn as an unmitigated instruction: “In the morning, it’s important that

you go-“, but then she cut herself off and provided an account at least indexing

a thinking around children safety (“Sometimes there are not any grown-ups

here”). This accounting element displays an understanding of performing a

delicate action, and contribute to softening

the instruction which follows “so you have to bring him into ‘kjøkkenet’ [the

kitchen]”. On the other hand, the choice of the verb you have to indicates a very strong right on her own behalf to

decide how the arrangement should be.

Albeit Case 2 and Case 3 represent clear

instances of what Palludan calls the teaching tone, several weeks had gone

since the start-up of the semester. Why

did these direct ways of socializing the parents occur this late? Had the staff

waited for the parents to adapt to the routines on their own before

intervening? Another explanation for this delayed intervention might be that my presence made them become more

reflective and thus conscious of the deviances. As mentioned, after noticing

that not all children were followed into the kitchen, I asked one of the staff

whether this was desired or not. Hence, my presence might have induced the

staff to monitor the rules more than usual; this is also known as the

observer’s paradox. But what is most surprising about these instances is

perhaps not the advice-giving itself, but that the teaching tone in little

degrees is balanced with small-talk or other affiliating actions embodying an

exchange tone. Although this study has not examined how the parents felt about

being objected to these socializing actions, the encounters in Case 2 and 3 had

in my opinion what Goffman would call a face-threatening quality (Goffman, 1967). The staff in question seemed to

lack the professional informality

needed to constitute an affiliating atmosphere when guiding the parents. It

should be noted that other instances of giving instructions were observed in

this kindergarten, which were given in a warmer and more recognizing

style, thus, the point here is not to establish all socializing actions as bad on their own but to focus on how they

are produced in social interaction.

Passing problems

Few think of institutions as determining human conduct, in Gulløv’s

wording “Institutions are simultaneously committing and dynamic frames around

formalized communities” (Gulløv, 2017,

p. 41). However, in both of the cases

mentioned above, the staff’s socializing actions seemed to be successful; the next

day both of the parents followed their child into the kitchen or at least to

the doorstep. Even the parent’s realization of the routine very much depends on the cooperation of the professional

part, who is the one entitled to acknowledge that the child is being delivered

in an appropriate manner. In this respect, the mother in Case 2 had certain passing problems, and a

comment from the care provider on this particular event is very interesting as

it conveys a reasoning around what might be the staff’s collective project of

socializing minority parents to follow the routine.

One morning, the mother from Case 2 came a few steps into the kitchen saying hello,

I would say with a normal loud voice, and from my chair at the side of the room I returned her greeting. There was

one care provider in the room who was sitting at the table with her back at the

doorway. She was talking with a child and did not recognize that two children

(both with minority background) were delivered behind her back. One of the

mothers went into the office of the nursery manager, while the mother who said

hello without being heard, waited a moment before leaving. Soon the care

provider at the table discovered that one of the children had arrived. She took

up her iPad and I told her that the other child also had been delivered. The

care provider then asked me: “They did not come in?” (they may here be referring to both cases). I told her that the

mother in question did, but that she was not noticed. The care provider then

said: “Oh yes, I sat the other way”. The oh,

yes preface suggests this to be a here-and-now discovery to her (Heritage, 1984). After a pause an account followed: “We try to teach them to come in and

communicate with us in the kitchen. This is also about attitudes to kindergarten. Some think of it more as storage”.

The noun we

in the utterance “we try to teach them to come in and communicate with us” suggests

that teaching parents to come in and talk with the staff is not her personal

opinion, but a collective project, she is talking on behalf of a professional we (See Drew &

Sorjonen, 1997 p. 97 about use of personal pronoun). Strictly speaking, the utterance

says nothing about the ethnicity or the socio-cultural background of the them, so why do I hear the term them in this utterance to be parents

with minority background? Is it because I use my common sense knowledge? Now

while background knowledge certainly matters, this is not sufficient to explain

my inference. Following an ethnomethodologically way of thinking, indexicality

is the rule in human interaction, not the exception, and sequence is the most important sense-making

vehicle. In this instance, the care provider produces her utterance (we try to

teach them) without a lengthy pause to her prior utterance (oh yes, I sat the

other way). Neither the turn is linguistically designed as launching a new

topic, it is easily heard as an extension of the existing project of figuring

out what just happened. Thus, it is my reflexive knowledge about how

conversational actions tend to be packed, rather than factual background

knowledge alone, which explains why I hear it this way. Still, the care

provider’s choice of noun after I have explained that the particular mother was

not noticed is interesting indeed. By saying them rather than she, a

first name, the mother of X and so forth, she refers to a group of people, not

to a singular person. Moreover, the group in question is alluded to as people

(some) who think day kindergarten is

about storing, and this undermining description constructs them as a negative contrast group to people knowing better, which

obviously includes the staff, the more competent we.

Regardless of ethnic origin, parents are often

not talked to in delivery scenes, hence, this utterance may imply a thinking

suggesting that talking to the staff is particularly important for minority

parents. Moreover, the account “we try to teach them to come in and communicate

with us in the kitchen” is ambiguous as it is not apparent whether this in

Scott and Lyman’s (1968) sense represents an excuse (denying

her own responsibility for the incident), or a justification (denying the

pejorative qualities of her actions). Taken as an excuse, minority parents have

been taught to come in and talk to the staff in the kitchen, thus unstated; if the

mother had followed this advice, she would not have gone unnoticed by the care

provider and the incident becomes the mother’s own fault. In this version, the

account is easy to hear as a complaint over the mother’s non-complying conduct.

However, the same utterance can also be understood as a justification (Scott &

Lyman, 1968). The incident of not noticing the

mother is then not a bad thing, but something inducing parents to enter the

kitchen and get in touch with the staff. Hence, to achieve this, a certain management of inaccessibility can even

be used to integrate parents into the kindergarten

culture. However, as the oh, yes

preface suggests, the presence of the mother to be a here-and-now discovery to

her (Heritage, 1984), it is perhaps more appropriate to

interpret this as complaint after all (the turn was designed for me, but I

chose to treat it as an explanation of what we do, rather than as a complaint,

thus in my interpretation, it was

sufficient for me to nod rather than sympathise).

Getting the staff into the

wardrobe area

In this section, I will try

to balance the impression of parents being socialized in a unilateral fashion. Albeit mostly adapting to

the staff’s actions, parents are also actors who sometimes try to negotiate the

institutional terms. In an interview with a majority mother, a personal strategy for getting the staff’s attention in

the morning was revealed. She told that she often puts her head into the

department and says hello to the staff, and very often someone from the staff

will come out in the wardrobe area and meet them. I asked whether she thinks

all parents would be met in this way, but she thought it would be different for

parents who are not as much on as she

is, for instance very cautious parents or ethnic minority parents. During the

observation period, I observed a scene

which could remind of this strategy of claiming attention.

A minority father with a quite small child used

to come into the kitchen, carrying the child on his arm while an older sibling

would wait in or nearby the doorway. The father would proceed to a table with

grown-ups and other children and he would put the child into one of the baby chairs.

Then one of the staff would stand up and say that the child does not need to

sit there if she had eaten at home. One day something interesting happened at

an unusually quiet early watch. The older sibling showed himself in the doorway

and waves to one of the staff, standing at the kitchen bench, to make her come

out in the wardrobe area. The care provider was doing some paper work and she said in a quite low voice

and without looking up at him that “X [the name of the child] can come into the

kitchen”. She thus rejected the sibling’s request to come out in the wardrobe

area. The boy disappeared for a moment, and when he came back he had a

desperate expression on his face. Though hard to say for sure, it is much

likely that the older sibling was mediating his father’s preferences, rather

than his own. Soon after, the child and the father entered the room, this time

the child walked on her own feet. The father stopped

in the doorway and gently pushed the child toward another staff member who approached

them.

At this moment, there were just a few children in the kitchen and one of the staff could

easily have disappeared out for a moment, thus the rules of the institution are

possibly not very easy to get around. This is not to suggest that parents

cannot be “institutional entrepreneurs” (see Gulløv,

2017, p. 51 ) and change institutional routines

and arrangements, but probably this is perhaps more likely to happen at the

system level when parents act like a

group.

The scene also indicates

that the practice of delivery in the kitchen is extra problematic when it comes

to toddlers. In her master thesis, Haug (2016, p. 29) describes the exchanges between

parent and child as an “intimacy practice” where the staff in comparison is

more of a bystander. But Haug’s fieldwork was conducted in a department with

older children. When it comes to toddlers, it is perhaps more appropriate to

say that the care provider is an active participant and co-operator in the

intimacy practice. When toddlers are handed over in the wardrobe area, the care

provider needs to physically position her body close to the child and the

parent, and the child goes from the arms of the parent into the arms of the

care provider. Very often the care provider will hold the child when she is

kissed goodbye by the parent. the kitchen arrangement makes this bodily

cooperation difficult. The staff usually sit at the table and entertain the

children, and they did not stand up when a parent showed up. As long as the

care provider sits at the table it is natural to see her as busy or inaccessible, thus, this places the

parent in an interactional ambiguous situation in terms of what to do. In the example, this ambivalence is managed by placing

the child in a chair at the table. Thus, his actions can be understood in light

of the interactional context embedded in this particular material structure,

rather than the father’s lack of background knowledge (not knowing the

arrangement or the Norwegian kindergarten

culture).

Discussion

The kitchen-routine appeared to be a somewhat demanding arrangement for

the parents to take part in, especially when it comes to delivering toddlers. Most

likely, the structure is particularly demanding for minority parents, to whom delivering in the kitchen is also a public

display of ethnicity and language skills as well as good family relations.

Possibly, the arrangement may be seen as a case of institutional discrimination

(Kamali, 2005), where, albeit not intended by

anyone, routines and arrangements do not function equally well for all groups.

In this case, it is hard to see that the

arrangement functions very well for any group as financial concerns lie behind,

but it probably works even worse for parents and children with a minority

background. Information about the arrangement had been given at a parent

meeting, which not all attended, and, since the meeting was given in Norwegian,

understanding might have been an issue to some parents. Moreover, information

about the staffing schedule had not been distributed to the parents, thus the

burden to figure out the arrangement of the day was very much up to the

parents.

The analysis focused on what happened in the three deviant cases where the parents did

not follow the children into the kitchen as expected. Would the staff socialize

these parents to follow the routine, and how was this performed? In Case 1

where the parent had a majority background, the staff did not do anything

during the observation period to change conduct, in contrast to the two other

cases, where the parents had a minority background. The micro analysis of the staff’s socialization-in-action confirms

Palludan’s impression that also parents with a minority background are met by a

teaching tone, rather than an including exchange tone (Palludan, 2005,

p. 138). In Case 2 the mother was

indirectly (“We are in the kitchen now”), and directly (“Very nice if you

can…”) advised accompanying her child

into the kitchen. In Case 3 it is perhaps more appropriate to say that the

father was being instructed on what to do (“you have to bring him”). However,

it should be added that several weeks had passed without the staff’s

intervention, thus passivity (Bundgaard &

Gulløv, 2008) is perhaps the most appropriate

characterization of their overall orientation. If so, the teaching tone may be

better understood as a last resort. All in all, the staff seemed to be in short

of the professional informality needed to balance the sociological and everyday

meanings of the term socialization (where the latter means to be sociable).

However, it should be noted that regardless of the parents’ sociocultural

background, the exchange tone seemed to be quite rare in the parent-staff

interaction as the staff tended to focus on giving the child a good reception.

The socialization was successful as the parents in Case 2 and 3 changed conduct

and started to come into the kitchen or in the doorway. On the other hand, the

staff was not prone to make an exception

from the routine and come out in the wardrobe area to meet the parents.

Actions designed at socializing (minority)

parents may be performed in a more or less tactful manner, but can we, in this

case, assume bad intentions on behalf of

the staff? Following Bourdieu, Palludan (2005, 2007) understands the teaching tone as a

structural phenomenon. Partly, the issue is understood as the minority

children’s’ communicative competence (their habituated cultural capital), which

makes the teaching tone natural to adopt for the staff to be able to

communicate at all. But she also notices that the teaching tone is at work even

when minority children speak Danish fluently. This is explained as an effect of

the staff’s unconscious categorization of minority

children as less capable. This way of reasoning is in line with newer

perspectives on discrimination as systemic, in terms of unconscious actions or

unfortunate consequences of rules (Rogstad &

Midtbøen, 2010, p. 45). In contrast to individual

discrimination, the systemic discrimination is not intended or acknowledged by

the performing actors (ibid). This new focus on systemic discrimination has

been seen as a gain since the issue of discrimination then can be discussed without blaming concrete persons for being

racists. On the other hand, this has also

been considered to be a weakness (Rogstad &

Midtbøen, 2009, p. 10).

From an ethnomethodological perspective, it is problematic to reduce this

issue to the play of actor less structures.

Following the perspective of racialization the utterance “We try to teach them

to come in and communicate with us in the kitchen” should primarily be seen as

an echo of the oriental way of thinking, which constructs minority groups as the other in contrast to a complacent we. Thus,

the professional is unconsciously carrying out a dominant thinking and an

institutional routine, without seeing the excluding side effects caused by her

praxis. But from an ethnomethodological perspective, the relationship between

social structure and social interaction is not given or external to the actor

in the Durkheimian sense, Wilson (1992) argues: “Rather, externality and

constraint are members’ accomplishments, and social structure and social

interaction are reflexively related rather than standing in causal or formal

definitional relations to one another” (Wilson, 1992,

p. 27). Institutional rules and routines

are thus not realized by judgemental dopes, but by competent members who are

not naïve about social structures and who know how to utilize various

interactional resources to realize projects in talk.

The site of discrimination is thus neither primarily at the individual level (othering

as an individual cognitive process) or at an abstract cultural level (the

oriental way of thinking) but at the middle level of social interaction where

people enact their daily business, such as socializing each other. Any action

should therefore be appreciated as an

accomplishment in its own right and in

this case, the distinction we/them is

part of an account excusing (Scott &

Lyman, 1968) her action of not noticing a

parent. The care provider could have chosen to produce a different account, for

instance, an account blaming the routine

or her own actions rather than the parents, but she did not (and I for myself

could have responded in a different way too). Hence, in our everyday lives we

all are co-producers of cultures in the settings we inhabit, but luckily, for

organizations willing to scrutinize their practices, change is possible.

References

Andenæs, A. (2011). Chains of care:

Organising the everyday life of young children attending day care. Nordic

Psychology, 63(2),

49-67. https://doi.org/10.1027/1901-2276/a000032

Andersen, C. E., Engen, T. O., Gitz-Johansen, T., Kristoffersen, C. S.,

Obel, L. S., Sand, S., & Zachrisen, B. (2011). Den

flerkulturelle barnehagen i rurale områder [The multicultural kindergarten in

rural areas] Høgskolen i Innlandet.

Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1967). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of

knowledge. London:

Penguin.

Bourdieu,

P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice

(Vol. 16). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511812507

Bundgaard,

H., & Gulløv, E. (2008). Forskel og

fællesskab: Minoritetsbørn i daginstitution. København: Hans Reitzel.

Drew, P., & Sorjonen, M.-L. (1997). Institutional Dialogue. In T. A. E. van Dijk (Ed.), Discourse as Social Interaction. Discourse

Studies: A Multidisciplinary Introduction. Volume 2. London: Sage

Publication.

Døving,

C. A. (2011). Hva

er en minoritet? Retrieved from http://www.hlsenteret.no/kunnskapsbasen/livssyn/minoriteter/hva-er-en-minoritet/hva-er-en-minoritet

Garfinkel,

H. (1967). Studies in Ethnomethodology.

Cambridge: Polity.

Goffman,

E. (1967). Interaction ritual: Essays on

face-to-face behavior. New York: Pantheon Books.

Goodwin,

C., & Heritage, J. (1990). Conversation Analysis. In Annu. Rev. Anthropol. (Vol. 19, pp. 283-307). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.19.100190.001435

Gulløv, E. (2017). Institution - formaliserede fællesskaber. In E. Gulløv, G. B. Nielsen, & I. W.

Winther (Eds.), Pædagogisk antropologi.

København: Hans

Reitzel Forlag.

Haug, M. (2016). Praksis der hjem

og barnehage møtes i hverdagen - en studie av interaksjon mellom foreldre,

personale og barn. (Master),

Høgskolen i Oslo og Akershus, Oslo.

Heritage,

J. (1984). A Change-of-State Token and Aspects of its Sequential Placement. In

J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures

of Social Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. .

Kamali, M. (2005). Ett europeisk

dilemma: Strukturell/institutionell diskriminering. (SOU 2005: 41).

Kulick,

D., & Schieffelin, B. B. (2008). Language Socialization. In A. Duranti

(Ed.), Wiley Blackwell Companions to

Anthropology Ser.: A Companion to Linguistic Anthropology (1). Williston:

Williston, GB: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

Palludan,

C. (2005). Børnehaven gør en forskel.

København:

Danmarks Pædagogiske Universitets Forlag.

Palludan,

C. (2007). Two Tones: The Core of Inequality in Kindergarten? International Journal of Early Childhood, 39(1),

75-91. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03165949

Pike,

K. (1967). Language in relation to a

unified theory of the structure of human behavior. The Hague: Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783111657158

Psathas,

G. (1995). Conversation Analysis: The

Study of Talk-in-Interaction. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412983792

Rogstad, J., & Midtbøen, A. (2009). Rasisme og diskriminering: Begreper, kontroverser og nye perspektiver.

Oslo: Forskningsrådet.

Rogstad, J., & Midtbøen, A. H. (2010). Den utdannede, den

etterlatte og den drepte: Mot en ny forståelse av rasisme og diskriminering. Sosiologisk

tidsskrift, 18(01), 31-52.

Scott,

M. B., & Lyman, S. M. (1968). Accounts. American

Sociological Review, 33(1), 46-62. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092239

SSB. (2017). Barnehagedekningen fortsetter

å øke. Retrieved from https://www.ssb.no/utdanning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/barnehagedekningen-fortsetter-a-oke

Utdanningsdirektoratet. (2018, 15.02.2018). Nøkkeltallene i Barnehagefakta. Retrieved from https://www.barnehagefakta.no/om-nokkeltallene

Wilson,

T. P. (1992). Social Structure and the Sequential Organization of Interaction.

In D. Boden & D. H. Zimmerman (Eds.), Talk

and Social Structure: Studies in Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis

(pp. 23-43).

Wooffitt,

R. (2005). Conversation Analysis and

Discourse Analysis: A Comparative and Critical Introduction: United

Kingdom: Sage Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849208765