NJCIE 2017,

Vol. 1(2), 29–46

http://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.2600

World-Class or World-Ranked

Universities? Performativity and Nobel Laureates in Peace and Literature

Brian D.

Denman[1]

Senior Lecturer, University of New

England, Australia

Copyright the author

Peer-reviewed article; received 12 January 2018;

accepted 24 February 2018

Abstract

It is erroneous to draw too many

conclusions about global university rankings. Making a university’s reputation

rest on the subjective judgement of senior academics and over-reliance on

interpreting and utilising secondary data from bibliometrics

and peer assessments have created an enmeshed culture of performativity and

over-emphasis on productivity. This trend has exacerbated unhealthy competition

and mistrust within the academic community and also

discord outside its walls. Surely if universities are to provide service and

thrive with the advancement of knowledge as a primary objective, it is

important to address the methods, concepts, and representation necessary to

move from an emphasis on quality assurance to an emphasis on quality

enhancement.

This overview offers an analysis of the

practice of international ranking. US News and World Report Best Global

Universities Rankings, the Times Supplement World University Rankings, and the

Shanghai Jiao Tong University Academic Ranking of World Universities are

analysed. While the presence of Nobel laureates in the hard sciences has been

seized upon for a number of years as quantifiable evidence of producing

world-class university education, Nobel laureates in peace and literature have

been absent from such rankings. Moreover, rankings have been

based on employment rather than university affiliation. Previously

unused secondary data from institutions where Nobel peace and literature

laureates completed their terminal degrees are presented.

The purpose has been to determine whether including peace and literature

laureates might modify rankings. A caveat: since the presence of awarded Nobel

laureates affiliated at various institutions results in the institutions

receiving additional ranking credit in the hard sciences of physics,

chemistry, medicine, and economic sciences, this additional credit is not recognised in the approach used in this study. Among

other things, this study suggests that if educational history were used in assembling the rankings as opposed to one’s

university affiliation, conclusions might be very different.

Keywords:

Global University Rankings; Research Quantums;

Quality Higher Education

Reformative reflections on education: an introduction

In the

spirit of Schriewer’s transnational intellectual

networks, knowledge has often become characterised and shaped

by reformative reflections on education over time (Schriewer,

2004). Friedman contends that societal knowledge has been

shaped by outward and inward culture. Regarding the former, he states,

“…the more you have a culture that naturally glocalizes,

the more your culture easily absorbs foreign ideas and global best practices

and melds those with its own traditions” (Friedman, 2007, p. 422).

Like

outward-seeking educational reforms, universities are prime examples of how

outward or inward nation-states shape and define educational policy. Global

university rankings are examples of ways that help to promote outward-seeking

institutions. International agencies such as university league tables, UNESCO’s

Global Monitoring Reports (see UNESCO Global Education Monitoring

Report, n.d.), and other international data sources—including bibliometrics

(e.g. h-index, Scopus and peer-to-peer impact factors) have increasingly become

viewed as policy-oriented, multilateral and/or national educational reform

initiatives. These are pursued to promote, negate, or

change the direction of knowledge advancement simply by the interpretation of

evaluators, typically from the nation-state, institution or accrediting

organisation or authority. Notwithstanding the need to ensure that data used in

these instruments contain pieces of truth, the data collected and methodology

employed may often be subjective, biased, anecdotal, and inexact. The research

requires what Bleiklie (2014, p. 383) argues is a

question of conceptual clarity. Not only can the choice of

research methodology be questioned, but also how data were collected,

the approach and timing, the number of cases under study, and how data are

interpreted. With regard to the latter, Moodie (2017)

cautions that metrics are tools for transferring evaluation and monitoring from

experts, who are usually the people conducting the activity, to people and

bodies who are distant in location and seniority, often senior management

located centrally.

Van Raan (2005) also points out that metrics have been

insufficiently developed to be utilised in working with large-scale data for

comparative studies, charging that quick and dirty analyses have largely

been misused and abused for purposes of just in time decision-making

when better and more advanced indicators could have been developed and made

available.

Comparing

universities as a whole can also be quite problematic as well. Benneworth and Sanderson (2009) argue that universities

that serve regional, rural and remote communities are at a disadvantage as far

as rankings are concerned, as demand for their services is often limited and

this circumstance leads to the suggestion that they have low or little impact

and are always in catch-up mode to amass demands for knowledge. Their

marginalised position propels notions of inferiority that puts the question as

to whether universities should be ranked in concert

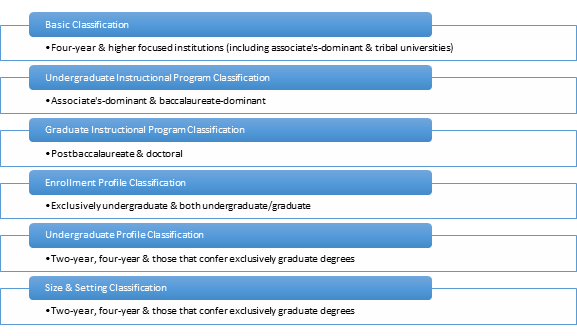

with their location and constituencies. In a positive step, the Carnegie

Classification of Institutions of Higher Education (2015) has classified six

types of institutions in an attempt to differentiate between types of

institutions:

Table 1: Modified version of the

Carnegie Classification of universities and other higher education institutions

Source:

Carnegie Classifications of Institutions of Higher Education, 2015, http://carnegieclassifications.iu.edu/downloads/CCIHE2015-FlowCharts-01Feb16.pdf

Beyond

location and constituent differences, gaps in fiscal resources and endowments

in long-established universities in the West have left many institutions at a disadvantage,

which has led to increased: 1) competitive pressures of the global marketplace;

and 2) institutional pressures emanating from performance-based measures generated from funding bodies (e.g. World Bank, IMF, OECD,

government) (see Marginson, Kaur, & Sawir 2011).

Since the

turn of the 21st Century, data analysis from rankings, metrics, and

performance-based measures in the field of education has resulted in what many

term as New Public Management which, in turn, has led to a wave of

increased accountability based on evidence-based quality assurance and quality

control measures, often at the expense of process. Birnbaum, like many,

viewed these as “…self-correcting mechanisms that monitor organizational

functions and provide attention cues, or negative feedback, to participants

when things are not going well” (Birnbaum 1989, p. 49). This, in a further

development, has led to questions of whether universities serve the public

or the public good. Marginson and Considine differentiated universities by defining those

that might be classified as enterprise, entrepreneurial,

and corporate universities, concluding that the enterprise university

encapsulated a balanced mix of economic and academic dimensions that maintained

research survivability, but in an environment of increased competition and

performativity (Marginson and Considine,

2000, p. 5). In this discussion, the question is raised

as to what happens in the assessment and evaluation processes when there may be

policies, which fail to comply with expectations across cultures and

nation-states? How are standardised instruments used

when quality education is varied due to student ability and capability? Can processes be improved to avoid data being misused or

abused? Finally, who ultimately determines authority in establishing what

quality constitutes, and how is quality enhanced with

such measures over time? Generally speaking, when any

of these issues are raised, there is often outcry about data collection and the

quality of the methodologies employed, but with scant mention given to the

depth of analysis and nature of assessment. The field of education may be considered a non-exact science, but its standards in

research need not be compromised. While quantitative research methodology in

education may help to explain and predict phenomena to establish, confirm, or

validate relationships and to develop generalisations that may contribute to

theory, much of the research employed in interpolating global data sets is

still largely qualitative. The work is not only exploratory in nature but it

builds on reformative reflections that build theory from the ground up. Moran

and Kendall (2009) contend that different methodologies produce illusions of

education due to how education is typically viewed as

a field of study. While Baudrillard (1994) identifies

education as a number of simulations—in other words not reality—the act and pursuit of educational research identifies its weakness in

its interdisciplinarity, and “…[that] this will come

to mean that critiques of what might be seen as current inadequate practices

and policy are only, in a sense, illusionary critiques” (Moran & Kendall,

2009, p. 328).

This

analysis does not necessarily address what methodologies are

employed to describe international comparisons in educational data.

Instead, it is intended to shed light on the validity

of the research, meaning the accuracy, meaningfulness, and credibility of the

research as a whole. This has major implications for global organisations,

which rest institutional reputations on not only the credibility of the data

collected but also warranting that the data analysed are pieces of truth

when viewed as a contribution to overall knowledge advancement. Moreover, when

viewing the data as an aggregate whole, this approach can assist in making

generalisations about the world beyond specific situations, interventions, and

contexts.

Overseas expansion and globalisation of higher

education

The globalisation of higher education has become increasingly valued,

particularly in terms of overseas recognition of world-class

universities, international rankings, and competition among university

researchers. The Information Age has not only transformed the

way we communicate and collect information, it has also led to some unforeseen

consequences: the standardisation of curricula (Bologna Process, 2018);

increased levels of accreditation and accountability; and a general shift

towards a utilitarianism within professional, applied degrees, much to the

chagrin of those who endorse Newman’s idea of a university (Rothblatt, 2006, p.

52). Regarding the latter, Newman’s idea of a university was to simply

disseminate universal knowledge for the purpose of

teaching all who were ready and able. It was intended

for preparing the well-rounded individual rather than reinforcing the

advancement of the nation-state. Peripatetic, itinerant, and wandering scholars

too are increasingly more mobile—both literally and virtually—but are becoming more inclined to seek educational opportunities for

economic gain rather than intellectual well-roundedness. This is becoming

increasingly apparent in times of economic uncertainty as evidenced in the

Global Financial Crisis of 2008–2011. Moreover,

students have opted for professional specialised degree pursuits because of

their obvious need to seek gainful employment upon successful completion of the

degree.

All the

above has resulted in a general shift from viewing higher education as

something of social value to something that is more of an investment. This may

be due in part to the theory of human capital, formulated by Theodore W.

Schultz in 1960 (Alladin, 1992). Human Capital Theory

helped to justify the expansion of higher education by postulating that the

more education a population receives, the greater the benefits in the economy.

While individual investment in education is clearly on the increase—particularly in the case of

enrolment in private universities—there is a general perception that higher education serves the public

good. This, unfortunately, is beginning to wane. The commodification and

advancement of knowledge comes at a cost, and while research continues to be an

imperative in the modern university, those institutions identified as poorly

resourced cannot continue to meet rising demand. Notwithstanding the content of

the Carnegie Classification of universities, there continues to be no universal

form or definition of what constitutes a university, yet world-rankings of

universities continue to shape and manipulate what is

perceived as quality and excellence. As Hazelkorn rightly emphasizes,

Rankings are

a manifestation of what has become known as the worldwide ‘battle for

excellence’, and are perceived and used to determine the status of individual

institutions, assess the quality and performance of the higher education

system, and gauge global competitiveness. (Hazelkorn,

2015, p. 1)

Rankings

differ from accreditation, the latter of which has been viewed historically as

an award of merit vested by the Pope or, at times, the Emperor in granting licence

(Studium Generale) to teach

at a university (Neave, 1997). While accreditation agencies have proliferated

since the late 1990s at international, national and disciplinary levels,

carriage is given to highly prescribed and

standardised criteria to audit education—in all its various forms—by peer panels of experts who

specialise in various disciplines and who are aware of and sensitive to the

educational contexts relative to the audited institution in question. The

recent wave of mergers and change of status for several university colleges to

universities in the Nordic region helps to highlight the increased importance

of these agencies and peer panels. Rankings, on the other hand, have galvanised

the commodification of knowledge. As a result, there is a cost associated with

knowledge advancement, and while research continues to be

an imperative in the 21st Century university, those institutions identified as

poorly resourced cannot continue to meet rising demand for research excellence.

According to Marginson and van der Wende,

This

[ranking] process has been encouraged in many nations by policies of

corporatisation and partial devolution based on governance by steering from a

distance and more plural income raising, a model of provision that reflects informal

cross-border norms influenced by practices in the English-speaking nations and

the policy templates of the World Bank. (Marginson

& van der Wende, 2007, p. 308)

This

reputational race to the top in the league with the impetus to improve greater public

accountability and transparency, has led to an unfair advantage given to

resource-rich institutions—predominantly Anglo-centred—and those that excel in the hard sciences.

Table 2: Listing of

university league tables, country of origin, and methodologies used

|

Name of organisation |

Academic Ranking of World Universities |

THE World University Rankings |

QS World University Rankings |

US News and World Report Best Colleges Rankings |

Performance Ranking of Scientific Papers for World

Universities |

Ranking Web of World Universities |

CHE-Excellence Ranking |

|

Company or institution & country |

Shanghai Jing Tiao University (China) |

Times Higher Education (UK) |

Quacquarelli Symonds (UK) |

U.S. News and World Report (USA) |

Higher Education Evaluation and Accreditation Council of Taiwan

(Taiwan) |

Cybermetrics Lab (CCHS) (Spain) |

Center for Higher Education

(Germany) |

|

Methods |

Highly cited researchers (20%) |

Teaching (30%) |

Academic reputation (40%) |

Graduation and retention rates (22.5%) |

Research excellence (40%) |

Presence rank |

Number of publications in the web of science |

|

|

Papers in Nature and Science (20%) |

Research reputation & income (30%) |

Student-to-faculty ratio (20%) |

Undergraduate academic reputation (22.5) |

Research impact (35%) |

Impact rank |

Citations (normalised to the international standard) |

|

|

Papers indexed (20%) |

Research ciations (30%) |

Research citations per faculty member (20%) |

Faculty resources (20%) |

Research productivity (25%) |

Openness rank |

Outstanding researchers |

|

|

Alumni (10%) |

International outlook (7.5%) |

Employer reputation (10%) |

Student selectivity (12.5%) |

|

Excellence rank |

Number of projects in the Marie Curie Programme |

|

|

Per capita performance (10%) |

Industry income (2.5%) |

Proportion of international faculty (5%) |

Financial resources (10%) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Graduate rate performance (7.5%) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alumni giving rate (5%) |

|

|

|

Multiple

Sources: Academic Ranking of World Universities; World

University Ranking Methodologies Compared; Ranking

Web of Universities; US

News & World Report Education.

As a result of the increase in compliance policies and regulatory

standards imposed on universities and their institutional partnerships,

performance-based measures have been pursued at nation-state levels which, in

turn, has led to unforeseen consequences such as the following: 1) increased

pressure to publish in Anglophone journals and/or those journals that have been

ranked nationally or by discipline; 2) evidence of research impact (measured

mostly by bibliometrics) as opposed to formative

assessments on impact (societal, community and/or individual), since the latter

is often considered too subjective; and 3) micro-managerialism

of academic performance, collegial competition for increased specialisation

and, in isolated cases, collegial sabotage.

Methodologies

currently employed by university world ranking organisations also suggest that

world rankings are here to stay. The obsession on the part of universities to

be identified as world-class do not, however, reflect

world rankings. Variables and percentages used in rankings change over time, methods

are contested, and the exercises used to evidence quality often help to

undermine the very essence of what a university is and how it sets itself apart

from others. World rankings prompt universities to focus on similarities based

on a narrow listing of measureable variables. World-class

universities, on the other hand, may be preconceived as elitist in certain

parts of the world, but are increasingly viewed as world-class due to their

emphasis on differentiation and carving out their own path.

Confidence crisis in academia

Husén (1991) identifies the modern university as an

entity working towards many different goals while at the same time training

professionals. Apart from expectations to improve educational access, promote

equality, and offer quality instruction, “…it is expected to contribute to the

extension of the frontiers of knowledge by high-quality research” (Husén, 1991, p. 184). While academic staff generally tend

to give their loyalty to their discipline more than to their employer (the university),

if a student demand system dictates what degrees are kept or discarded, this

creates angst in maintaining a strategic presence in one’s discipline or field

of study whether research-active or not. A further complication derives from an

increasing obsession with evidence-based performance measures—necessary prerogatives and

interventions in higher education at present. Gaps between administrative and

academic staff are growing and with increased significance. The organisational

culture of the university appears to be increasingly affected by entities which use performance reporting as a management strategy

for punitive measures and entities which promote and encourage academic

excellence and quality. Notwithstanding a need to bridge

these fissures as it should be understood that the ultimate goal is to achieve

similar like-minded outcomes, the divide appears most notable in the pursuit of

knowledge and its advancement for the academic while parenthetically, the

administrator is mobilizing in a quest for greater efficiencies and

effectiveness in doing more for less and keeping an eye on the bottomline.

An ageing

workforce and inadequate succession planning further exacerbates this angst,

particularly when universities are asked to slash

budgets and casualise staff appointments. The

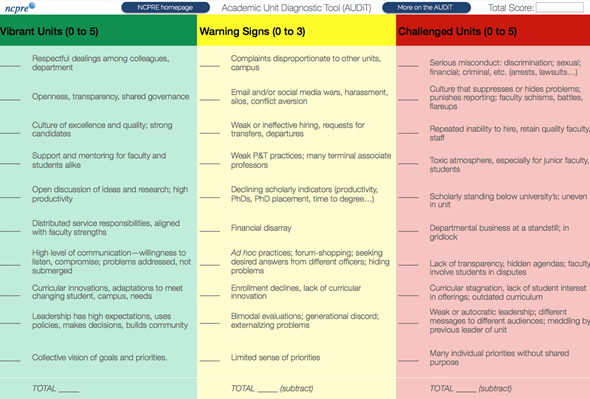

National Center for Professional and Research Ethics

(NCPRE) recently developed a new academic unit diagnostic tool (AuDiT) that indexes three levels of academic departmental

culture: vibrant, warning, and challenged (see NCPRE, 2018). This tool helps

measure how the degree of health in a given academic department, by seeking to

judge vibrant, warning, and challenged departmental

characteristics and/or nuances. The index suggests that the greater the level

of dysfunctional management, the greater the anxiety experienced by staff.

Table 3: NCPRE’s Academic Unit Diagnostic Tool (AUDiT)

Source: National Center for

Professional & Research Ethics, https://ethicscenter.csl.illinois.edu/academic-leadership/ccc/audit/

This

anxiety is transferred to the prospective

undergraduate student, who may not necessarily know at the time of university

matriculation how to choose an appropriate degree or major. Policies and

structures developed to assess the alignment between education and employment

are still in the development stage (e.g. OECD Higher Education Programme,

2018). Balancing life and work continue to be a struggle, and standards run the

risk of faltering when divisive forces cannot find a common goal of education’s

ultimate purpose. As Alladin observes, “[t]he

university has become a place where a student is trained for an occupation

rather than given a broad education in traditional fields” (Alladin,

1992, p. 6).

Given

increased regulation, standardisation, and quality control measures intended to

improve accountability, metrics and benchmarking are increasingly tied to

funding and hence, becoming an evidence-based necessity. The hope is that any

form of analytics focuses upon a culture of academic excellence and quality,

and that the quality of evidence is tightly monitored and

justified; otherwise, it becomes cost-ineffective and dysfunctional. As

economic imperatives also become increasingly the norm, the alignment between

education and employment will continue to drive transformational change to the

traditional disciplines, forcing universities to consider developing

qualifications that are highly specialized and/or cross-disciplinary

or custom-tailored to meet the individual needs of the consumer, the student.

Husén

(1991, p. 184) rightly suggests that academic competence must be forced to yield

to the power of numbers. The advent of the Information Age has shifted the

focus away from Newman’s idea (see Rothblatt 2006) to a more utilitarian

approach. An understanding of the university as an entity and its possible

future can also be attained by the use of

demographics. As an example, demographic data, compiled from secondary sources,

allow researchers to analyse, interpolate, and replicate from different

perspectives (Smith, 2010). This helps broaden opportunities for discovery

through comparative analysis and leads to an increasing need to understand

situational, country contexts. While caution should be exercised when

interpolating results from secondary sources such as the UNESCO Global

Monitoring Reports, the data utilised can help verify estimations and make

predictions for the foreseeable future. This includes

world rankings, as variables change over time as does institutional leadership

and context.

The risks and benefits of international education

comparisons

Currently, international education comparisons tend to promote the

globalisation of education in terms of increased economic trade and human

capital. It is predicted that in order for comparative

education research to be more useful and practicable for nation-states and

institutions alike in the future, there will be an increasing need for students

to possess the aptitude and inclination in understanding, interpreting, and analyzing statistical data from large-scale data sources.

The higher the quality, the greater the sense of purpose and ownership of

knowledge acquisition and advancement. Moreover, it is hoped

that a spillover effect may offer greater benefits

that might redefine the current system of performativity and productivity. The

risks, if further exacerbation continues, is a lack of depth, rigour and

robustness in research, which can lead to ambiguities in exceptions to the

rule, a general lack of environmental contexts at institutional or local

levels, simplistic prescriptions for change, or normative prescriptions of policy

and practice.

In the

following research to demonstrate how one variable can change the whole dynamic

in world university rankings, the utility of using secondary data from the

Nobel Peace Institute (Norway) and the Nobel Prize Organisation (Sweden) helps

to show how different rankings can be affected. The

purpose of this research honours the contribution of the non-exacting science

of education in its various forms. While peace and literature are not necessarily directly aligned with the field of

education, the understanding of education’s ultimate purpose of

well-roundedness is considered as offering a contribution to the advancement of

knowledge. Generally seen as being the most reliable and used, the Shanghai

Jing Tiao rankings award the highest points to

institutions which have or have had Nobel laureates in the hard sciences—10% within their respective

rankings. However, peace and literature are not listed in the current

calculations due to the fact that they are not in the

hard sciences. This may be purposeful in the sense that peace and literature

are, by nature, subjective fields of study. This research has been undertaken

to consider adding Nobel laureates in peace and literature to highlight those

institutions that have produced and/or acknowledged the contributions of these

notable individuals. This undertaking suggests that a further ranking of

universities worldwide might yield a new ranking of institutions that, among

other things, value and recognize the contributions of education—a non-exacting science—a field of study that helps to

expand and broaden knowledge and its advancement.

Table 4: List of Nobel laureates (literature; peace)

according to country and institution where highest degree was

obtained

|

Country |

Universities |

Nobel laureates (literature) |

Nobel laureates (peace) |

|

Algeria |

University of Algiers |

Albert Camus |

|

|

Argentina |

University of Buenos Aires National University of La Plata |

|

Carlos Saavedra Lamas Adolfo Perez Esquivel |

|

Australia |

(University of Cambridge) |

Patrick White |

|

|

Austria |

University of Vienna (2) University of Graz (Jagiellonian University) |

Elfriede Jelinek |

Alfred Hermann Fried |

|

Bangladesh |

Chttagong College |

|

Muhammad Yunus |

|

Belarus |

Belarusian State University |

Svetlana Alexievich |

|

|

Belgium |

Ghent University (Dominican University) Universite

libre de Bruxelles University of Louvain |

Maurice Maeterlinck |

Georges Pire Henri La Fontaine Auguste Marie Francois Beernaert |

|

Bosnia & Herzegovina (Yugoslavia) |

(University of Graz) |

Ivo Andrić |

|

|

Bulgaria |

(University of Vienna) |

Elias Canetti |

|

|

Canada |

University of Western Ontario (St. John’s College, Oxford) |

Alice Munro |

Lester Bowles Pearson |

|

Chile |

University of Chile |

Pablo Neruda Gabriela Mistral |

|

|

China |

Beijing Normal University (2) Beijing Foreign Studies University Lhasa’s Jokhang Temple |

Mo Yan Gao Xingjian |

Liu Xiaobo Dalai Lama (Tenzin Gyatso) |

|

Colombia |

(Harvard University) |

Gabriel Carcia Marquez |

Juan Manuel Santos |

|

Czech Republic (Czechoslovakia) |

|

Jaroslav Seifert |

Baroness Bertha Sophie Felicita von Suttner,

nee Countess Kinsky von Chinic

und Tettau |

|

Denmark |

University of Copenhagen Technical University of Denmark |

Karl Adolph Gjellerup & Henrik Pontoppidan Johannes Vilhelm Jensen |

Fredrik Bajer |

|

Egypt |

Cairo University (2) (New York University School of Law) Alexandria University |

Naguib Mahfouz |

Mohamed El Baradei Yasser Arafat Mohamed Anwar Sadat |

|

Finland |

University of Helsinki University of Oulu |

Frans Eemil Sillanpää |

Martti Ahtisaari |

|

France |

Ecole Nationales

des Chartes University of Paris (8) College Stanislas de Paris Ecole Normale

Superieure (2) University of Aix-en-Provence Lycée Bonaparte Lycée Henri-IV (2) Aix-Marseille University University of

Strasbourg Lycée Louis-le-Grand (2) University of Bordeaux (2) (University of Oxford) (University of Bristol) |

Patrick Modiano J.M.G. Le Clézio Claude Simon John-Paul Sartre Saint-John Perse François Mauriac André Gide Roger Martin du Gard Henri Bergson Anatole France Romain Rolland Frédéric Mistral Sully Prudhomme |

René Cassin Albert Schweitzer Léon Jouhaux Ferdinand Buisson Aristide Briand Léon Victor Auguste

Bourgeois Paul Henri Benjamin Balluet d’Estournelles de Constant, Baron de Constant de Rebecque Louis Renault Frederic Passy |

|

Germany |

(West University of Timisoara) Berlin University of the Arts University of Cologne University of Munich University of Bonn (2) University of Jena University of Göttingen (2) University of Kiel (Harvard University) (University of Oslo) University of Oldenburg University of Leipzig University of Marburg Heidelberg University Evangelical Seminaries of Maulbronn and Balubeuren |

Herta Müller Günter Grass Heinrich Böll Nelly Sachs Thomas Mann Gerhart Hauptmann Paul von Heyse Rudolf Cristoph Eucken Theodor Mommsen |

Henry A. Kissinger Willy Brandt Carl von Ossietzky Ludwig Quidde Gustav Stresemann |

|

Ghana |

(Massachusetts Institute of Technology) |

|

Kofi Annan |

|

Greece |

(University of Paris (2)) |

Odysseas Elytis Giorgos Seferis |

|

|

Guatemala |

Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala |

Miguel Angel Asturias |

Rigoberta Menchú Tum |

|

Hungary |

|

Imre Kertész |

|

|

Iceland |

|

Halldór Laxness |

|

|

India |

University of Calcutta Samrat Ashok

Technological Institute (United Services College) |

Rabindranath Tagore Rudyard Kipling |

Kailash Satyarthi |

|

Iran |

University of Tehran |

|

Shirin Ebadi |

|

Ireland |

National College of Art and Design St. Patrick’s College, Maynooth (Queen’s University of Belfast)(2) Irish School of Ecumenics University College Dublin Loreto Abbey, Rathfarnham, Ireland Trinity College, Dublin |

Seamus Heaney Samuel Beckett George Bernard Shaw William Butler Yeats |

John Hume David Trimble Betty Williams Mairead Corrigan Seán MacBride |

|

Israel |

(Staff College, Camberley) |

Shmuel Yosef Agnon |

Yitzhak Rabin |

|

Italy |

Dominican University (University of Bonn) Brera Academy Polytechnic University of Milan Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa |

Giosuè Carducci Grazia Deledda Luigi Pirandello Salvatore Quasimodo Eugenio Montale Dario Fo |

Ernesto Teodoro Moneta |

|

Jamaica |

University of the West Indies |

|

|

|

Japan |

(University of East Anglia) University of Tokyo (3) |

Kazuo Ishiguro Kenzaburō Ōe Yasunari Kawabata |

Eisaku Satō |

|

Kenya |

University of Nairobi |

|

Wangari Muta Maathai |

|

Liberia |

(Harvard University) (Eastern Mennonite University) |

|

Ellen Johnson Sirleaf Leymah Gbowee |

|

Lithuania |

Vilnius University |

Czesław Miłosz |

Bernard Lown |

|

Macedonia |

(Loreto Abbey, Rathfarnham, Ireland) |

|

Mother Teresa (Saint Teresa of Calcutta) |

|

Mexico |

(University of California Berkeley) (Academy of International Law, Netherlands) |

Octavio Paz Lozano |

Alfonso Garcia Robles |

|

Myanmar (Burma) |

(University of London) |

|

Aung San Suu Kyi |

|

Netherlands |

Academy of International Law, Netherlands Hague Academy of International Law University of Leiden |

|

Tobias Asser |

|

Nigeria |

University of Ibadan |

Wole Soyinka |

|

|

Norway |

University of Oslo (3) |

Sigrid Undset Knut Hamsun Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson |

Fridtjof Nansen Christian Lous Lange |

|

Pakistan |

|

|

Malala Yousafzai |

|

Peru |

(Complutense University of Madrid) |

Mario Vargas Llosa |

|

|

Poland |

Jagiellonian University Warsaw University (3) Warsaw Rabbinical Seminary (New School for Social Research, New York) |

Wisława Szymborska Isaac Bashevis Singer Władysław Reymont Henryk Sienkiewicz |

Joseph Rotblat Lech Wałęsa Shimon Peres Menachem Begin |

|

Portugal |

Pontifical Salesian University, Portugal |

José de Sousa Saramago |

|

|

Romania |

(University of Paris) |

|

Elie Wiesel |

|

Russia (Soviet Union) |

Rostov State University (University of Marburg) Moscow State University (2) P.N. Lebedev Physics Institute of the Soviet

Academy of Sciences (FIAN) |

Joseph Brodsky Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn Mikhail Sholokhov Boris Pasternak Ivan Bunin |

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov |

|

Saint Lucia |

(University of the West Indies) |

Derek Walcott |

|

|

South Africa |

University of the Witwatersrand (Kings College London) Adams College, South Africa University of South Africa Potchefstroom University for Christian Higher Education (University of Texas, Austin) |

J.M. Coetzee Nadine Gordimer |

F.W. de Klerk Nelson Mandela Desmond Mpilo Tutu |

|

South Korea |

Kyung Hee University |

|

Kim Dae-jung |

|

Spain |

Complutense University of Madrid (2) University of Madrid University of Salamanca |

Camilo José Cela Vicente Aleixandre Juan Ramón Jiménez Jacinto Benavente José Echegaray |

|

|

Sweden |

University of Stockholm (2) Uppsala University (6) |

Tomas Tranströmer Harry Martinson Eyvind Johnson Pär Lagerkvist Erik Axel Karlfeldt Carl Gustaf Verner von Heidenstam Selma Lagerlof |

Alva Myrdal Dag Hjalmar Agne Carl Hammarskjold Lars Olof Jonathan (Nathan) Söderblom

Hjalmar Branting Klaus Pontus Arnoldson |

|

Switzerland |

(Heidelberg University) (Evangelical Seminaries of Maulbronn

and Balubeuren) University of Zurich |

Hermann Hesse Carl Spitteler |

Élle Ducommun Charles Albert Gobat Jean Henry Dunant |

|

Timor-Leste |

(Pontifical Salesian University) (Hague

Academy of International Law) |

|

Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo Jose Ramos-Horta |

|

Trinidad & Tobago |

(University of Oxford) |

V.S. Naipaul |

|

|

Turkey |

Istanbul University |

Orhan Pamuk |

|

|

United Kingdom |

Staff College, Camberley University of Cambridge (4) Kings College London Royal Academy of Dramatic Art University of Oxford (3) Royal Military Academy Sandhurst (Harvard University) University University of Glasgow |

Doris Lessing Harold Pinter William Golding Sir Winston Churchill Bertrand Russell T.S. Eliot John Galsworthy |

Philip J. Noel-Baker Lord (John) Boyd Orr of Brechin Cecil of Chelwood, Viscount (Lord Edgar

Algernon Robert Gascoyne Cecil) Arthur Henderson Sir Norman Angell (Ralph Lane) Sir Austen Chamberlain William Randall Cremer |

|

USA |

University of Minnesota (2) Howard University Northwestern University Stanford University University of Mississippi Yale University (2) Harvard University (8) New School for Social Research, New York Massachusetts Institute of Technology University of California Berkeley Vanderbilt University Georgia Southwestern College Johns Hopkins University (2) Boston University California Institute of Technology Virginia Military Institute Bryn Mayr College Cornell University Rockford University Columbia University Marietta College New York University Cumberland University |

Bob Dylan Toni Morrison Joseph Brodsky Saul Bellow John Steinbeck Ernest Hemingway William Faulkner Pearl S. Buck Eugene O’Neill Sinclair Lewis |

Barack H. Obama Albert Arnold (Al) Gore Jimmy Carter Jody Williams Norman E. Borglaug Martin Luther King Jr. Linus Carl Pauling George Catlett Marshall Ralph Bunche Emily Greene Balch John Raleigh Mott Cordell Hull Jane Addams Nicholas Murray Butler Frank Billings Kellogg Charles Gates Dawes Thomas Woodrow Wilson Elihu Root Theodore Roosevelt |

|

Vietnam |

|

|

Lê Đúc Tho |

|

Yemen |

Sana’a University |

|

Tawakkol Karman |

|

Zimbabwe |

(Adams College, South Africa) |

|

Albert John Lutuli |

NB:

Institutions listed in parenthesis are institutions located outside of the Nobel

laureate’s home of origin.

Notes:

-

36

Nobel laureates studied in a country other than their home country (anomaly:

University of West Indies)

-

5

were activists

-

9

who were born in one country but acknowledged for their contributions in

another (Israel/Palestine/Germany/Bulgaria/Romania/Macedonia/Yugoslavia/Poland/Ukraine/Belarus)

-

44

had no formal education; 1 has yet to finish her formal education abroad

-

12

were imprisoned, assassinated, exiled, expelled (strongly advised to emigrate),

persecuted, or determined to leave their country of origin

-

1

declined the award (peace); 1 declined the award (literature)

-

Burma,

Colombia, Chile, Hungary, Iceland, Israel, Liberia, Macedonia, Mexico, Pakistan,

Peru, Saint Lucia, Timor-Leste, Vietnam, Yugoslavia, and Zimbabwe are the only

countries that hold a Nobel laureate (peace/literature), but with no

institutional affiliation

Table

5: University rankings based on Nobel laureates (peace; literature)

|

Rank |

Institution |

|

1 |

Harvard

University (USA) |

|

2 |

University

of Paris (France) |

|

3(tied) |

Oxford

University (UK) Uppsala

University (Sweden) |

|

4 |

Cambridge

University (UK) |

|

5(tied) |

University

of Vienna (Austria) Complutense

University of Madrid (Spain) University

of Oslo (Norway) University

of Tokyo (Japan) Warsaw

University (Poland) |

|

6(tied) |

Beijing

Normal University (China) Cairo

University (Egypt) Ecole

Normale Superieure

(France) Lycée Louis-le-Grand (France) Lycée Henri-IV (France) University

of Bordeaux (France) University

of Bonn (Germany) University

of Göttingen (Germany) Moscow

State University (Russia) Adams

College (South Africa) University

of Stockholm (Sweden) Queen’s

University of Belfast (UK) Johns

Hopkins University (USA) University

of Minnesota (USA) Yale

University (USA) |

Table 6: University rankings according to

international league tables (2017)

|

Rank |

Shanghai Jing Tiao |

THE |

QS |

US News & World |

|

1 |

Harvard University |

University of Oxford |

Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

Princeton University |

|

2 |

Stanford University |

California Institute of Technology |

Stanford University |

Harvard University |

|

3 |

University of Cambridge |

Stanford University |

Harvard University |

University of Chicago; Yale University |

|

4 |

Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

University of Cambridge |

University of Cambridge |

Columbia University; Stanford University |

|

5 |

University of California Berkeley |

Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

California Institute of Technology |

Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

Sources:

Academic Ranking of World Universities, http://www.shanghairanking.com;

World University Rankings 2016-2017, https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/2017/world-ranking#!/page/0/length/25/sort_by/rank/sort_order/asc/cols/stats;

QS World University Rankings, https://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/world-university-rankings/2016;

U.S. News & World Report Releases 2017 Best Colleges Rankings, https://www.usnews.com/info/blogs/press-room/articles/2016-09-13/us-news-releases-2017-best-colleges-rankings

Material observations

World-class and world-ranked universities differ as the

former place emphasis upon difference and the latter upon comparable similarity.

The only shared dimensions of both are the challenges to financial,

and administrative capacity given the increasing social demands for higher

education (Martin et al. 2007). Variables such as institutional and research

reputation are highly subjective and limited to the exposure of differing

educational systems. Ranking universities as a whole also undermine the

qualities of institutes, schools, and departments that otherwise might attract

notice and be valued. Productivity statistics and international involvement

vary considerably from year to year and, while such variables are useful to

determine social and individual rates of return, the shelf-life

of the data are short-lived and difficult to utilise to make comparisons

year-to-year.

When comparing

various methodologies for world-rankings of universities, it is clear that

their task is fraught with ambiguities. In other words, ranking is not an

exacting science. By concentrating on one variable used in the Shanghai Jiao

Tong (ARWU) ranking relating to highly cited researchers and alumni, it was

found that Nobel peace and literature laureates were not counted as opposed to

those in the hard sciences. This may be because both peace and literature are considered soft sciences and thus, the perceived value

in their individual and social rate of return is equivocal and open to

contestation.

Given the

notion that world-class universities emphasize

institutional difference, the addition of Nobel peace and literature laureates

to league tables would change current league table configurations of

institutional ranks. By developing a specialised

listing of institutions on the basis of the presence of Nobel laureates in

peace and literature reveals a hallmark of difference and, moreover, captures

the essence of what universities are striving for: namely, the desire to be

recognised as world-class as opposed to simply being world-ranked.

The process

of collecting data on Nobel laureates in literature and peace produced some

additional findings. Many Nobel laureates were listed

in more than one country, even when individuals fled, left, or were persecuted

in their country of origin. Among the top five institutions listed in Table 5,

14 Nobel laureates completed their studies in a second country, suggesting that

mobility is not only rife but that one’s identity may not necessarily be

associated with where one is born. While knowledge may not necessarily be the

province of any one nation-state, the marketability of world-class

scholars such as Nobel laureates propels nation-states and institutions to

recognise high achievement.

The

university rankings based on Nobel laureates (Table 5) in comparison to

university rankings based on league tables (Table 6) reflect a sharp contrast

and set of distinctions. Notwithstanding the noticeable difference in rankings

of universities from other nation-states, many of these institutions offer

mediums of instruction other than English. By changing one variable, Nobel

laureates (literature and peace), which have been omitted in league tables for

whatever reason, there is scope to consider specialist rankings as standalone,

as they help offset those institutions that appear to meet international

benchmarks that are becoming increasingly standardised. In addition, they may

help to promote institutions that are unique, different, or set apart from

others.

References

Academic Ranking of World

Universities (2017). Retrieved 22 February 2018, http://www.shanghairanking.com

Alladin,

I. (1992). International Co-operation in Higher Education: The Globalization of

Universities. Higher Education in Europe, vol XVII,

(4), 4–13, Unesco

European Centre for Higher Education. Bucharest, Romania. https://doi.org/10.1080/0379772920170402

Baudrillard,

J. (1994). Simulacra and simulation. University of Michigan press.

Benneworth,

P. & Sanderson, A. (2009). The Regional Engagement of Universities:

Building capacity in a sparse innovation environment. Higher Education

Management and Policy, 21(1), 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1787/hemp-v21-art8-en

Birnbaum, R. (1989). The

Cybernetic Institution: Toward an integration of governance theories. Higher

Education, 18(2), 239–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00139183

Bleiklie,

I. (2014). Comparing University Organizations across Boundaries. Higher

Education, 67(4), 381–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-013-9683-z

Bologna Process (2018). European

Higher Education Area and Bologna Process. Retrieved 28 February 2018, http://www.ehea.info

Bridgestock,

L. (2017) World University Ranking Methodologies Compared. Retrieved 22

February 2018, https://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings-articles/world-university-rankings/world-university-ranking-methodologies-compared

Carnegie Classification of

Institutions of Higher Education (2015). Flow Charts. Retrieved 7

December 2017, http://carnegieclassifications.iu.edu/downloads/CCIHE2015-FlowCharts-01Feb16.pdf

Friedman, T. (2007). The

World is Flat. A Brief History of the Twenty-First

Century. New York: Picador.

Hazelkorn,

E. (2015). Globalization and the Reputation Race. Rankings and the Reshaping

of Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137446671_1

Husén, T.

(1991). The idea of the university. Changing roles, current crisis, and future

challenges. Prospects, 21(2), 169–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02336059

Marginson,

S. & Considine, M. (2000). The Enterprise

University: Power, Governance and Reinvention in Australia. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Marginson, S. & van der Wende,

M. (2007). To rank or to be ranked: The

impact of global rankings in higher education. Journal of Studies in

International Education, 11(3/4), 306–329.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315307303544

Marginson,

S., Kaur, S. & Sawir, E. (Eds.) (2011). Higher

Education in the Asia-Pacific. Strategic Responses to Globalization. Higher

Education Dynamics (Vol. 36). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1500-4

Martin, M., (Ed.) (2007). Cross-Border

Higher Education: Regulation, Quality Assurance and Impact. UNESCO

International Institute for Educational Planning, Vol 1. Paris: UNESCO.

Moodie,

G. (2017). Unintended consequences: The use of metrics in higher education. Academic

Matters, (Winter 2017). Retrieved 7 December 2017, https://academicmatters.ca/2017/11/unintended-consequences-the-use-of-metrics-in-higher-education/

Moran, P. & Kendall, A.

(2009). Baudrillard and the End of Education. International

Journal of Research and Method in Education, 32(3), 327–335.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17437270903259873

NCPRE (2018). National Center for Professional & Research Ethics,

Retrieved 28 February 2018, http://ethicscenter.csl.illinois.edu

Neave, G. (1997). The

European Dimension in Higher Education. Background document to the

Netherlands seminar on "Higher Education and the Nation State", Center for Higher Education Policy Studies. Twente, The Netherlands, (April

1997).

OECD Higher Education

Programme (2018). The Assessment of Higher Education Learning Outcomes.

Retrieved 22 February 2018, http://www.oecd.org/education/imhe/theassessmentofhighereducationlearningoutcomes.htm

Ranking Web of Universities

(2018) Ranking Web of Universities Edition of 1R Semester of the Year 2018.

Retrieved 22 February 2018, https://www.upc.edu/ranquings/en/upc-at-international-rankings/rankings/ranking-web-of-universities

Rothblatt, S.

(2006). The modern university and its discontents: The fate of

Newman's legacies in Britain and America.

Cambridge University Press.

Schriewer,

J. (2004). Multiple Internationalities: The emergence of a world-level ideology

and the persistence of idiosyncratic world-views. In C. Charle,

J. Schriewer & P. Wagner (Eds.), Transnational

Intellectual Networks: Forms of Academic Knowledge and the Search for Cultural

Identities (pp. 473–533).

Frankfurt: Campus Verlag.

Smith, E. (2010). Pitfalls and

Promises: The use of secondary data analysis in educational research. British

Journal of Educational Studies, 56(3), 323-339. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8527.2008.00405.x

Unesco Global

Education Monitoring Report (n.d.). Retrieved 22 February 2018, https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/

U.S.

News & World Report Education (2017). How U.S. News Calculated the Best

Global Universities Rankings. Retrieved 22 February 2018, https://www.usnews.com/education/best-global-universities/articles/methodology

Van Raan, A. F. J. (2005). Fatal Attraction: Conceptual and methodological problems in the ranking of universities by bibliometric methods. Scientometrics, 62(1), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-005-0008-6

[1] Corresponding author: bdenman@une.edu.au