NJCIE 2019, Vol. 3(2), 20-36 http://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.2659

A Comparison of University Curriculum in Special Teacher Education in Finland and Sweden

Marjatta Takala [1]

Professor, University of Oulu, Finland

Marie Nordmark [2]

Senior Lecturer, University of Dalarna, Sweden

Karin Allard[3]

Lecturer, University of Örebro, Sweden

Abstract

This study analyses special teacher education (STE) curricula from six Finnish and seven Swedish universities through the lenses of inclusive education. The written academic curricula reflect scientific, professional, social, and ethical values, goals, and competencies in education, school, and society. The results show that Finnish and Swedish STE curricula have similarities and differences. The main focus is on removing barriers from learning. Finnish STE can be described as a “combo degree,” in which various learning difficulties are addressed, while Swedish STE is a specialization degree with five different options. Guided teaching practice as part of the studies is essential in Finnish education but does not exist as such in Sweden. Core values of inclusive elements were embedded in the curriculum of both countries, often in the form of co-operation as well as in the form of means of supporting all learners and of valuing learner diversity. Based on our results, we claim that STE can be described in terms of inclusive special education. The core contents of the STE curricula in these two countries are discussed and compared.

Keywords: curriculum; special teacher education; professional competence; inclusion

Introduction

In this article, we study the written curricula of special teacher education in two Nordic countries, Finland and Sweden. Our study attempts to find answers to the following questions: What is the curricular framework of special teacher education (STE) in Finland and Sweden? What is the common content of STE curricula in Finnish and Swedish universities? What are the main curricular similarities and differences in these two countries? These issues are studied using the inclusive core values as a framework, in order to determine whether there are elements of inclusive education in the curricula.

Today the leading educational policy in most Western countries is inclusion (Ainscow, Booth & Dyson, 2006; European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2018; Lomazzi, Borisch & Laaser, 2014; UNESCO, 1994). Special education solutions seem contradictory to this policy, which can be one reason why little research is done on STE in a Nordic as well as in an international context. In Florida, Darling, Dukes & Hall (2016) studied possible universals in STE, but they did not go into details regarding the content. When the content of the studies has been examined, STE has primarily been compared to general teacher education (Cochran-Smith & Dudley-Marling, 2012; Feng & Sass, 2013). Nevertheless, the European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education (2011) underlines that the awareness of diversity among student teachers needs to be raised and inclusive values should be included in all teacher education. That is why we study STE in an inclusive framework. However, inclusive education is challenging to define. Although inclusion and ‘education for all’ were agreed to be goals in education already in UNESCO (1994), there is no clear consensus what these concepts really mean (Bossaert, Colpin, Pijl & Petry, 2011; Norwich, 2013). Several researchers use these as meaning educating children with special educational needs in mainstream education (e.g. Day & Prunty, 2015; Schwab, Holzinger, Krammer, Gebhartdt & Hessels, 2015). However, that narrows the concept of inclusion to concern only special educational needs. But, if ‘education for all’ means to develop the full potential of every individual and inclusive education means the end of all discrimination and fostering social cohesion, the content of these concepts are quite similar, says Kiuppis (2014). It is crucial to keep in mind that inclusion does not mean just presence, but also increasing the participation and achievement of all children (Forlin, 2013; Qvortrup & Qvortrup, 2018).

In this article, we study STE curricula in Finland and Sweden through the lenses of inclusive education. The European Agency project on teacher education for inclusion (European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education, 2011) involved several countries during 2010-2011 and more than 100 educational professionals, who all were representatives from the European Commission, OECD- Centre for Educational Research and Innovation or from UNESCO- International Bureau of Education. A widespread agreement on how to define core values and teacher competencies in relation to them was achieved. We use the four core values from the agreement in this article, in order to study whether they are represented in STE. These core values, which are the theoretical framework of our article, are valuing learner diversity, supporting all learners, working with others, and personal professional development (see Watkins & Donnelly, 2014). As a teacher competence, valuing learner diversity means, for example, that learner differences are seen as resources and assets in education. Supporting all learners includes that teachers are supposed to have the competence to set high expectations for everyone’s achievement. Collaboration and teamwork with various stakeholders are seen as essential values. Finally, professional development is perceived to be a lifelong process, a possibility for teachers in an inclusive school. (Watkins & Donnelly, 2014) We assume that STE is in line with current educational policy and, as such, promotes inclusion. Nevertheless, it is often evaluated as segregating (Pijl, 2016). But, since some of the core values of inclusion are represented in STE curriculum, it could be seen as a curriculum that contains inclusive elements.

Although Finland and Sweden are similar social and democratic societies, educational differences exist. For example, the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) success has been much higher among Finnish 15-year-olds than among Swedish students of the same age (OECD, 2016; OECD, 2017). Sweden also has two types of special education professionals: special teachers who work mainly with pupils and SENCOs (special needs education coordinator) who work with adults and pupils. Finland has just special teachers. Teacher education has been offered as a master’s degree in Finland since 1979, but in Sweden, it has only been offered for subject teachers at secondary or upper secondary school since 2007 (Jakku-Sihvonen & Niemi, 2006; SOU 2008: 109). In addition, Finland has 2300 comprehensive schools (OSF, 2018), of which only 80 are private schools (YLE, 2015). Sweden has more private schools than Finland, in some municipalities even more than public schools, and the number is increasing (Dovemark & Erixon-Arreman, 2017; Malinen, Väisänen, & Savolainen, 2012). Finland has no regular compulsory national test system for primary education (grades 1-9), but Sweden does (Finnish National Agency for Education, 2017; the Swedish National Agency for Education, 2017). Involving two countries in the study can provide more perspectives than having just one country involved. There needs not to be contrasts between different countries, but rather linkages across space, time and place, especially between two neighbouring countries. That is why we approach them with the desire to understand the linkages to inclusive educational policy (see also Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017). We suppose that the special education-related needs are quite similar in two Nordic welfare states, both of which have 9-year compulsory education with special education services included (see also Arnesen & Lundahl, 2006; Lundahl, 2016).

Context

The Finnish Ministry of Education has formulated common criteria for teacher education. A teaching degree in Finland consists of 300 ECTS (credits in the European Credit Transfer System)[4] (except for the kindergarten teacher degree, which is at the bachelor’s level, consisting of 180 ECTS) (Niemi & Jakku-Sihvonen, 2006; Vitikka, et al., 2012). Finnish teacher education leads to different teacher degrees, like class, subject, or a special teacher’s degree. The last one provides professional competence to enable one to work as a special teacher (Finnish Council of State, 2004, § 19). A teaching degree in Sweden is 180 ECTS for a kindergarten teacher, 240 ECTS for a primary education teacher, 270 ECTS for a lower secondary education teacher, and 300-330 ECTS for an upper secondary education teacher. A special teacher, or a special education needs co-ordinator, SENCo (in Swedish special pedagogue) degree can only be obtained after an initial general teacher degree (Swedish Higher Education Authority, 2017; Swedish National Agency for Education, 2017). In many countries, special teachers are usually educated separately from general education teachers, with their own separate curriculum (Cochran-Smith & Dudley-Marling, 2012; Pijl, 2010). This is also the case in both Finland and Sweden.

In Finland, after a kindergarten, primary, or secondary teaching degree, STE comprises 60 ECTS, of which 20-25 ECTS (basic studies in special education) needs to be done before entering STE and the rest can be obtained in one year. In Sweden, a STE degree is 90 ECTS. A teaching degree and 1-3 years of teaching experience at a school, or in kindergarten, are required to start special teacher studies in Finland and Sweden (University of Helsinki, 2017; University of Stockholm, 2017). In comparison to students who enter directly into a regular teacher education program from school, this is a unique situation. STE students have experiences as teachers and have encountered challenging situations and pupils with special needs at school. In Finland, there is also another way to become a special teacher: one can study special education as one’s major for five years, and then, as part of these studies, pursue a special teacher degree. However, this article focuses on the most common method of earning a special teacher degree, which is after kindergarten, primary or secondary or upper secondary school teacher studies.

In Sweden, mainstream schools have either a special teacher or a SENCo, sometimes a school has both. Special teachers and SENCo’s support pupils and staff inside and outside the classroom. The tasks of these two occupational groups differ from one municipality to the next. The SENCo’s work is somewhat different and the reason for having two professions has historical roots (see, e.g. Göransson, Lindqvist, Klang, Magnusson & Nilholm, 2015a; Von Ahlefeldt Nisser, 2014). SENCo’s work primarily with teams and consult teachers. They also serve as a resource for the pupil’s health team. Conversely, special teachers have closer ties with classroom work (Göransson, Lindqvist, & Nilholm, 2015b). In this article, the focus in Sweden is on special teachers, whose work content and responsibilities resemble those of Finnish special teachers. There are, however, no SENCo’s in Finland working at schools with a similar work profile as Swedish SENCO’s (see also Takala & Ahl, 2014). Several municipalities have, however, a SENCO coordinating the special education system at the municipal level in Finland.

The studies for a STE degree for primary and secondary school teachers in Finland and Sweden are not differentiated by age groups; rather, they include aspects of primary, secondary, and upper secondary education. In Finland, they also include kindergarten education.

The content of the special education curriculum has had a deficit approach (see, e.g., Cobb, 2016), which focuses on the child as the cause of the problems. This could be seen in a study about Finnish STE curriculum (Hausstätter & Takala, 2008), in which central issues taught to future special teachers consisted of various difficulties as well as challenges in child development. The focus being on disabilities, and on the individual as the problem, reflects the medical model of disability (Reindal, 2008). The language we use to describe individuals with disabilities influences, for example, our expectations and interactions with them (Haegele & Hodge, 2016). We assume that the deficit, also called the medical model, is recessive in the 21st century, with the inclusive core values, such as valuing learner diversity and supporting all learners (see also Watkins & Donnelly, 2014). The social model of disability, focusing more on the environment, could serve STE and promote inclusive special education (see Hornby, 2015; Takala, Pirttimaa & Törmänen, 2009).

Method

The special teacher education (STE) curricula in Finnish and Swedish universities were collected from the website of each university. If essential information was not available from this source, the institute was contacted, and the information was obtained upon request. We studied the curriculum from all six universities offering STE in Finland (Universities of Eastern Finland, Helsinki, Jyväskylä, Oulu, Turku, and Vaasa). In Sweden, there are currently seven universities and three colleges offering STE. We limited our study to the universities in Sweden (University of Karlstad, Linköping, Linneaus, Uppsala, Stockholm, Umeå, and Gothenburg), and thereby excluded the colleges in order to have a similar number of universities from both countries. In addition, we focused on STE; the SENCo education is omitted from this analysis while there are no SENCo’s at school in Finland.

First, we investigate the framework of the education before we move on to the objectives and content of every course included in the STE program. The curricula are analysed using conventional and summative content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005; Kondracki, Wellman & Amudson, 2002; Saraisky, 2015), within the frame of inclusive education (Boot & Ainscow, 2002; Watkins & Donnelly, 2014). Content analysis can be defined as a process of bringing the meaning of data to the surface (Merriam, 2009). Conventional content analysis is used to condense data, and summative content analysis is used to quantify qualitative data when relevant. It is a powerful data reduction technique; it is a systematic, replicable technique for compressing many words of text into fewer content categories (Stemler, 2001).

Three researchers, two Swedish speaking and one Finnish speaking (who can also read Swedish), have read the data and analysed the contents: first separately and then jointly comparing and compressing the results. The trustworthiness was verified with several authors who read the source material (see also Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

This study has limitations. We only used curricula and course descriptions and did not study the literature or other material that the students had to read. Also, the Swedish SENCOs were excluded even though they belong to the whole picture of special education in Sweden. In addition, we only studied written curricula—not the implemented or learned ones. Nevertheless, the studied work content resembles what has been found in other studies related to this area (Göransson et al., 2015a; Hausstätter & Takala 2008).

Results

The Framework of Finnish and Swedish Special Teacher Education Curricula

All Finnish universities offering the 60 ECTS STE programmes, except one, have a minimum of 20-25 ECTS in basic special education studies as an admission requirement to the program. Swedish Universities offering the 90 ECTS STE programmes, offer 30 ECTS in one semester.

Three Finnish universities offer optional courses with 3-7 ECTS (University of Eastern Finland, Jyväskylä, and Turku), which means that students can choose some part of their studies. No specialization is possible; however, the optional courses can be seen as a small possibility to specialize. Only one Swedish university offers optional courses (Linneus). However, the Swedish STE is specialized in five directions (30 ECTS each): language, writing, and reading development; mathematical development; deafness and hearing; visual impairment and intellectual impairment/ learning disabilities. Stockholm University is the only university in our data that offers all five specialisations. Other universities offer specialization in one (Karlstad and Uppsala), two (Linneus), or three areas (Umeå, Gothenburg, and Linköping). The special teacher studies are mainly carried out part-time, and, therefore, last three years or STE is offered on a full-time basis over 1.5 years (Umeå). While STE is a kind of in-service training, it can be seen as professional development, which is a core value in inclusion.

In both countries, STE is offered as web-based education and as so-called campus education carried out at the universities. It is not possible to obtain the degree by participating in web-based classes only or by participating in campus-based classes only. In both countries, STE consists of a mix of web-based and campus located elements, which education means that students can work during their studies, but still have to be present at the university for several weeks in Finland (from 7 to 12 weeks), or for several days in Sweden (from 6 to 48 days/year). Using a mix of two different ways of study can be seen as inclusive. It costs to travel to study at the university, although the education itself is free. For some disabled students, it can also be easier to participate in web-based education. However, teachers have mixed views on web-based teaching (Erguvan, 2014).

The core of special teacher education in Finland and in Sweden

Three courses are common in STE at all six Finnish universities and have titles that are quite similar. The amount of ECTS for each course is presented in order to highlight the weighting of the courses in the total 60 ECTS (Finnish) and 90 ECTS (Swedish) STE-degree. These courses are Professional Expertise (5-6 ECTS), Guided Teaching Practice (5-10 ECTS), and Challenges in Language Development (3-5 ECTS). In addition, three other courses are included in the core of Finnish STE, namely Challenges in Socio-Emotional Development, in Reading and Writing, and Mathematical development, all 3-5 ECTS. The Swedish core has somewhat similar elements, although the titles of the courses differ. The core is formed of these themes: Special Teachers’ Areas of Responsibilities and Roles, Specialisation of a Special Teacher, and Perspectives on Special Education and Learning, all 5-10 ECTS. In addition, all seven Swedish universities have courses called Science Theory and Methodology (10-15 ECTS) and Independent Degree Thesis (15 ECTS).

The common core

The core courses Professional Expertise/Growth/Development in Finland and Special Teachers’ Areas of Main Responsibilities and Roles in Sweden have similar content and goals. The content includes both theoretical aspects of professional knowledge and practical skills, such as knowing and using various educational documents, writing an individual educational plan, knowing educational legislation, and applying various interventions and evaluation methods. This course also includes various aspects of co-operation with different stakeholders: “The student knows the basic principles of multi-professional work” (University of Turku, 2017). Similar content exists in Sweden: “The student should be able to demonstrate ability to be a qualified conversation partner and adviser in matters relating to children and pupils’ learning and knowledge development” (U. of Uppsala).

The Swedish five specialization courses have similar elements, but more ECTS than the Finnish shorter courses about Challenges in Language, Social and Emotional Difficulties or Reading, Writing or Mathematical development. These courses include typical and atypical development of, for example, language, speech, behaviour, reading, writing and mathematical skills, as well as rehabilitation related to these areas. In Finnish curricula, the goal, in relation to the core areas, is specified by the following wording: “The student knows difficulties in speech, language and communication, their background, evaluation, ways of support and rehabilitation” (U. of Turku, 2017), or “A student knows the typical development of reading and writing skills and recognises different developments both in technical reading and orthography, as well as in reading comprehension and productive writing” (U. of Oulu, 2017). The Swedish specialisation comprises approximately one-third of the total ECTS in education. The goal emphasises that: “The student should demonstrate in-depth ability to critically and independently carry out pedagogical writing and reading investigations and analyze difficulties for the individual in the learning environments where the student is taught.” (U. of Linneus)

The common core includes elements of teachers’ professionalism and aspects related to the diversity of development. These have links to all core values of inclusion. The curricula include issues related to valuing learner diversity, skills to support all learners, collaboration and consultation, including working with others, and issues related to teachers’ professional development for example in demands on critical thinking and reflection (see Watkins & Donnelly, 2014).

Differences

Although the STE is similar in several aspects in the two countries, differences are also visible. Guided teaching Practice is compulsory at every university in the Finnish data, but not at all in the Swedish data. Teaching practice is mainly split into two, three or four week periods. The students follow an experienced special teacher for some time, often one week, and then they teach, organise interventions and evaluate pupils. At the University of Jyväskylä, one goal for guided teaching practice is that “the student can plan and execute teaching based on individual needs.” Similar kinds of goals are written in the curriculum of every university regarding guided teaching practice. In addition, in the teaching practice, “the student can use the learned theories [...] and can adapt research and intervention methods learned during special teacher education” (U. of Jyväskylä). After the guided teaching practice, the students usually need to write a reflective report about the practice period. Although Sweden has no guided teaching practice, the students can practice new skills directly while working as teachers in school and at the same time studying STE part-time for three years. Nevertheless, they miss out on the opportunity of receiving advice or guidance from an experienced supervisor.

The methodology course in the Swedish universities focuses on both quantitative and qualitative methods, as well as on the research process. In the course Independent Degree Thesis, the student must demonstrate that he or she can undertake a small scientific study. The Finnish students have already written a Master’s thesis before entering into the STE program, but, if they want, they can study methodology. Some Finnish universities still ask their students to write a small thesis within the STE program, but not all.

The theme Perspectives on Special Education and Learning is common to all Swedish universities. The content focuses on historical and cultural perspectives in a societal context—for example, gender, class, ethnicity, and identity development. The key concepts are inclusion, normality, segregation, differentiation, and participation. All these perspectives and concepts are represented in various courses in Finnish STE but there is not a specific course dedicated to them.

The consultant role is mentioned in the context of co-operation in one or two courses, or in course titles, from six of the seven Swedish universities, but it is not mentioned in the Finnish courses or course titles.

The main difference between the STE in these two Nordic countries is the difference in focus. Finnish universities teach a little about several learning difficulties, while Swedish universities teach more about fewer learning difficulties. The Finnish degree is a combo-degree while the Swedish degree is more focused.

Special and/or Inclusive?

The word “inclusion” was seldom used in either countries’ curricula. In Finnish curricula, it was only listed in the content description as one theme in basic studies of special education (U. of Oulu 2017). One course title with the word inclusion was found from Jyväskylä University, namely: Inclusive Educational Environment and Co-operation, and only one course in the Swedish data refers explicitly to inclusion: Inclusion and Exclusion in Special Needs Education (U. of Uppsala 2016). However, the goals of several courses include the word inclusion in the text, such as: “creating inclusive learning environments for the pupils” (U. of Karlstad, 2016). Concepts related to participation (e.g. U. of Umeå, 2016) or design for all (U. of Oulu, 2017) can also be considered referring to inclusion. How about the inclusive values?

Traces of the core values of inclusion (see Watkins & Donnelly, 2014) were present in both Finnish and Swedish curricula. Valuing learner diversity could be detected in the way diversity was discussed in the texts. The curricula from both countries contained several courses that included the word challenges or problems in the course title. Traces of the deficit model (e.g. Reindal, 2008) could be seen in these titles that are referring to a difficulty, disability, or medical challenge: Challenges in Behaviour (U. of Helsinki), Challenges in Learning Mathematics (U. of Oulu), and Difficulties in language, writing and reading development (U. of Uppsala and Stockholm, 2016). However, some universities mention “Opportunities and Obstacles to Learning” (e.g. in U. of Linköping, 2016) and “Special Support for Language, Writing, and Reading Learning” (U. of Linneaus, 2016). The word opportunities give a more positive connotation in the title than the word challenges and does not reflect the deficit model (Reindal, 2008). Both the concept opportunities and the concept support were present in the titles (U. of Helsinki, 2017; U. of Turku, 2017) and therefore we claim that the deficit approach is not the only approach present, but the Finnish and Swedish curricula also underline the importance of focusing on the strengths and possibilities of the pupils (see Pickl, Holzinger, & Kopp-Sixth, 2016; Uusitalo-Malmivaara, 2015). This can implicitly be seen as an expression of valuing learner diversity and not seeing diversity as a problem.

Also, the core value supporting all learners was present. If a child has learning difficulties, the STE content presents students with available methods and interventions to work with the children. The curricula emphasize studies of both social and behavioral issues in order to be able to support all learners in schools. The core value of inclusion, supporting all learners, was also present in the STE curricula while the students had to study ethics and current educational documents, such as acts and national recommendations and educational legislation in both countries, where supporting all learners is discussed.

The core value working with others was more visible in the Swedish STE curricula in the form of consultation than in the Finnish one. Nevertheless, multi-professional work was underlined in both countries. The word co-operation was used in the titles and goals of several courses in both countries: “The student receives competencies […] to work in multi-professional teams, in different networks, and in the work community” (U. of Oulu, 2017). “A student is able to make and fulfil an IEP of an individual pupil in co-operation with other stakeholders” (U. of Umeå, 2016). Co-operation was also used in several titles: Participation and co-operational environment (U. of Eastern Finland) or Special teachers’ multi-dimensional co-operation (U. of Turku).

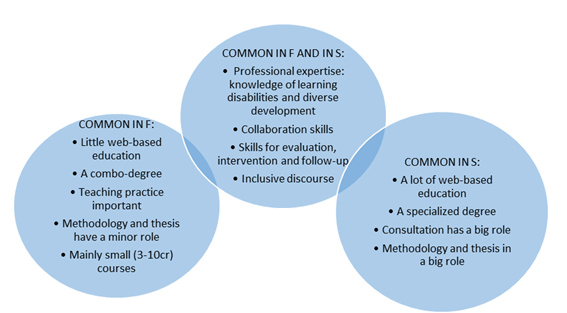

The core value Personal professional development was the goal of the whole year for the students, as the education itself is an in-service education. It was also a goal in descriptions of guided teaching practice in Finnish curricula and in descriptions of courses including independent thesis writing in Swedish curricula. Thus, we can speak of inclusive special education in the curricula, either explicitly with inclusive concepts like participation and a school for all in the text, or sometimes implicitly with texts about equality. The comparative results of the contents of STE are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Common and different contents of Special Teacher Education curriculum in Universities of Finland (F) and Sweden (S)

Discussion

A vision of STE in this research included recognizing and removing barriers to learning and participation. The key elements in the STE curricula in these two Nordic countries are professional expertise, including various skills and basic tools like individual educational plans, and a lot of information of the diversity of children’s development and in relation to that, various intervention methods. Co-operation is also at the core of STE as well as inclusive educational policy via national regulations. In addition, the Swedish STE includes writing a thesis and studying scientific methodology, which have already been done by Finnish students prior to their STE (see Jakku-Sihvonen & Niemi, 2006). Finnish STE includes several weeks of guided teaching practice which also means collaboration with colleagues. The European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education (2011) underlines that teaching practice needs to be supported by intellectual analysis and a clear understanding of theoretical issues in order to close the practice-theory gap.

According to an older study (Hausstätter & Takala, 2008), the core content of the Finnish STE contained teaching practice and three main areas: instruction in reading and writing difficulties, mathematical challenges, and behavioural challenges. Today, approximately 10 years after that research was carried out, we can see that changes have occurred. The core still includes knowledge of various challenges, but also other aspects, such as collaboration and inclusive values.

Both STE curricula include elements of web-based studies, however more so in Sweden. More campus-based education is carried out in Finland. Interestingly, teachers with higher internet self-efficacy seem to have higher motivation toward web-based professional development (see Kao, Wu & Tsai, 2011), which means that web-based studies may be segregative to some students.

Teacher education has been accused of being too homogenous and unwilling to take risks or try radically new approaches (McCall, 2017). Is inclusive education a risk? Is that a reason why Finland and Sweden, as well as many other countries, have separate special teacher education? The vision is not necessarily to do away with STE or to combine STE with general teacher education. However, they could benefit from approaching each other since, at school, general and special teachers have common responsibilities for the education of diverse learners (Da Fonte & Barton-Arwood, 2017; Naukkarinen, 2010).

The importance of globalisation is underlined in teacher education, while there is an increasing array of global problems in the 21st century (Xin, Avvardo, Shuff, Cormier & Doorman, 2016). Inclusive teacher education might respond to this need. The international and Nordic trend towards inclusive education is strong (Hausstätter, 2014; Nilholm, 2007; Pulkkinen & Jahnukainen, 2016; Thomazet, 2009), so it cannot be ignored in any teacher education. The STE curricula studied here had elements of the core values of inclusive education. Therefore, we could cautiously talk of inclusive special education while the philosophy and values of inclusion and the interventions and strategies of special education were combined (see also Hornby, 2015). Thus, it seems possible to be special and inclusive at the same time.

Although inclusive education is the leading educational policy in several countries today, other voices are being heard. In Sweden and in the USA, the neoliberal agenda points at other goals (e.g. accountability, flexibility and choice) than what the inclusive core values point at. In neoliberalism, there might be a hidden ableistic and normative agenda (Waitoller & Kozleski, 2015). National testing, as well as an increasing amount of private schools, like in Sweden (Dovemark & Erixon-Arreman, 2017; Swedish National Agenda for Education, 2017b), can be signs of this. Conceptions of teachers’ professionalism differ between countries. In England, they are shaped by a drive to raise standards and commercialize professionalism, while in Finland they are influenced by thoughts on teacher empowerment (Webb et al., 2004). Traditionally, Scandinavian countries have built their education on values representing equality. However, during the last 20 years, these countries have increasingly adopted market-led reforms of education, especially Sweden. It has allowed private providers to play quite a significant role in delivering education services (Wiborg, 2013). If neoliberalism has an impact on STE remains to be seen.

We can conclude that Finnish and Swedish special teachers receive a varied and diverse education, which gives them tools to work with pupils who struggle in learning as well as tools to work for inclusion. All in all, the STE is somewhere in between inclusion and exclusion if they are seen as extremes in a dimension (Qvortrup & Qvortrup, 2018). The place of STE in this dimension varies in different countries. In the era of inclusive educational policy, the STE curricula could (should?) include inclusive values and as such, become special and inclusive.

Acknowledgements

The Finnish Ministry of Education has supported the writing of this article.

References

Ainscow, M., Booth, T., & Dyson, A. (2006). Improving schools: Developing inclusion. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203967157

Arnesen, A-L., & Lundahl, L. (2006). Still social and democratic? Inclusive education policies in the Nordic Welfare states. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 50(3), 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/003138306007433136

Bartlett, L. & Vavrus, F. (2017). Comparative Case Studies: An Innovative Approach, Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education, 1(1), 5-17. https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.1929

Booth, T. & Ainscow, M. (2002). Index for Inclusion. Developing learning and participation in schools. Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education. Retrieved from https://www.eenet.org.uk/resources/docs/Index%20English.pdf

Bossaert, G.; Colpin, H.; Pijl, S. J. & Petry, K. 2011. Truly included? A literature study focusing on the social dimension of inclusion in education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 17(1), 60-79. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2011.580464

Botha, J., & Kourkoutas, E. (2016). A community of practice as an inclusive model to support children with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties in school contexts. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20, 784–799. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1111448

Cobb, C. (2016). You can lose what you never had. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(1), 52–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1073376

Cochran-Smith, M., & Dudley-Marling, C. (2012). Diversity in teacher education and special education: The issues that divide. Journal of Teacher Education, 63(4), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022487112446512

Da Fonte, M. A.; Barton-Arwood, S. M. (2017). Collaboration of General and Special Education Teachers: Perspectives and Strategies. Intervention in School and Clinic, 53(2), 99-106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053451217693370

Day, T. & Prunty, A. 2015. Responding to the Challenges of Inclusion in Irish Schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 30(2), 237-252. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2015.1009701

Darling, S. M.; Dukes, C.; Hall, K. (2016). What Unites Us All: Establishing Special Education Teacher Education Universals. Teacher Education and Special Education, 39(3), 209-219. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406416650729

Dovemark, M., & Erixon Arreman, I. (2017). The implications of school marketisation for students enrolled on introductory programmes in Swedish upper secondary education. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 12(1), 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197916683466

Erguvan, D. (2014). Instructor's Perceptions towards the Use of an Online Instructional Tool in an Academic English Setting in Kuwait. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology - TOJET, 13(1), 115-130. Retrieved from https://www.learntechlib.org/p/153667/

European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education (2011). Teacher Education for Inclusion Across Europe – Challenges and Opportunities. Retrieved from https://www.european-agency.org/sites/default/files/te4i-synthesis-report-en.pdf

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education. (2018). Promoting Common Values and Inclusive Education. Reflections and Messages. Retrieved from https://caldercenter.org/sites/default/files/CALDERWorkPaper_49.pdf

Feng, L., & Sass, T.R. (2013). What makes special-education teachers special? Teacher training and achievement of students with disabilities. Economics of Education Review, 36, 122–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2013.06.006

Finnish Council of State. (2004). Valtionneuvoston asetus yliopistojen tutkinnoista, 794/2004; § 19 [Statute of the degrees at the university]. Retrieved from https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/2004/20040794

Finnish National Agency for Education. (2017). Education system: Equal opportunities to high-quality education. Retrieved from https://www.oph.fi/english/education_system

Forlin, C. (2013). Changing paradigms and future directions for implementing inclusive education in developing countries. Asian Journal of Inclusive Education, 1(2), 19–31. Retrieved from http://ajie-bd.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/chris_forlin_final.pdf

Göransson, K., Lindqvist, G., Klang, N., Magnusson, G., & Nilholm, C. (2015a). Speciella yrken? Specialpedagogers och speciallärares arbete och utbildning. En enkätstudie. [Special professions? Special Education and Special Education teachers: A survey study]. Karlstad: Karlstad University Studies.

Göransson, K., Lindqvist, G., & Nilholm, C. (2015b). Voices of special educators in Sweden: A total-population study. Educational Research, 57(3), 287–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2015.1056642

Haegele, J. A. & Hodge, S. (2016). Disability Discourse: Overview and Critiques of the Medical and Social Models. Quest, 68(2), 193-206. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1143849

Hammerness, K. (2013). Examining features of teacher education in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 57(4), 400–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2012.656285

Hausstätter, S. R. & Takala, M. 2008. The core of special teacher education: a Comparison of Finland and in Norway. European Journal of Special Education, 23 (2), 121-134. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856250801946251

Hausstätter, R.S. (2014). In support of unfinished inclusion. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 58(4), 424–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2013.773553

Hornby, G. (2015). Inclusive Special Education: Development of a New Theory for the Education of Children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities. British Journal of Special Education, 42(3), 234-256. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12101

Hotti, U. (2012). Akateeminen opetussuunnitelma innovaationa. [The Academic Curriculum as an innovation. Students’ assessments of the subject-teacher curriculum in 2005−2008 as a pedagogical environment from the point of view of becoming a professional]. Doctoral thesis. Faculty of Behavioral Sciences. University of Helsinki, research number 337. Retrieved from https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/32787/Akateemi.pdf?sequence=1

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Jakku-Sihvonen, R. & Niemi, H. (2006). Research-based teacher education in Finland. Reflections by Finnish Teacher Educators. Finnish Educational Research Association, Turku.

Kao, C-P; Wu, Y-T. & Tsai, C-C. (2011). Elementary School Teachers' Motivation toward Web-Based Professional Development, and the Relationship with Internet Self-Efficacy and Belief about Web-Based Learning. Teaching and Teacher Education: An International Journal of Research and Studies, 27(2), 406-415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.09.010

Kelly, A. V. (2004). The curriculum: Theory and practice (5th ed.). London: Sage Publications.

Kiuppis, F. (2014). Why (not) associate the principle of inclusion with disability? Tracing connections from the start of the ‘Salamanca Process’. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 18(7), 746–761. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2013.826289

Kondracki, N.L., Wellman, N. S., & Amudson, D. R. (2002). Content analysis: Review of methods and their applications in nutrition education. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 34(4), 224–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60097-3

Lawton, D. (1973). Social change, educational theory and curriculum planning. London: Hodden and

Stoughton.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Lomazzi, N., Borisch, B., & Laaser, U. (2014). The millennium development goals: Experiences, achievements and what’s next. Global Health Action, 7, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.23695

Lundahl, L. (2016). Equality, inclusion and marketization of Nordic education: Introductory notes. Research in Comparative & International Education, 11(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745499916631059

Luoto, L., & Lappalainen, M. (2006). Opetussuunnitelmaprosessit yliopistoissa. [Processes in curriculum design at the universities.] Finnish Education Evaluation Centre, publication no. 10. Retrieved from https://karvi.fi/app/uploads/2015/01/KKA_1006.pdf

Malinen, O.-P., Väisänen, P., & Savolainen, H. (2012). Teacher education in Finland: A review of a national effort for preparing teachers for the future. The Curriculum Journal, 23(4), 567–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2012.731011

McCall, J. (2017). Continuity and Change in Teacher Education in Scotland--Back to the Future. European Journal of Teacher Education, 40(5), 601-615. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2017.1385059.

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research (3rd ed.). San Francisco: A Wiley Imprint.

Naukkarinen, A. (2010). From discrete to transformed? Developing inclusive primary school teacher education in a Finnish teacher education department. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 10(1), 185–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2010.01168.x

Niemi, H., & Jakku-Sihvonen, R. (2006). Research-based teacher education. In R. Jakku-Sihvonen & H. Niemi (Eds.), Research-based teacher education in Finland: Reflections by Finnish teacher educators (pp. 31–50). Painosalama: Turku.

Nilholm, C. (2007) .Perspektiv på specialpedagogik [Perspective on special education]. Studentlitteratur: Lund.

Nilsen, S. (2017). Special education and general education: Coordinated or separated? A study of curriculum planning for pupils with special educational needs. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(2), 205–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2016.1193564

Norwich, B. (2013). ‘How does the capability approach address current issues in special educational needs, disability and inclusive education field?’ Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 14(1), 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12012

OECD. (2016). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Sweden country note: Key findings. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/pisa/PISA-2015-Sweden.pdf

OECD. (2017). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Finland. PISA 2015. Key findings for Finland. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/finland/pisa-2015-finland.htm

OSF. (2017). Official statistics of Finland. Special education. Retrieved from http://www.stat.fi/til/erop/index_en.html

Pickl, G., Holzinger, A., & Kopp-Sixt, S. (2016). The special education teacher between the priorities of inclusion and specialization. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(8), 828–843. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1115559

Pijl, S. J. (2010). Preparing teachers for inclusive education: Some reflections from the Netherlands. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 10(1), 197–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2010.01165.x

Pijl, S. J. (2016). Fighting Segregation in Special Needs Education in the Netherlands: The Effects of Different Funding Models. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 37(4), 553-562. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2015.1073020

Pulkkinen, J., & Jahnukainen, M. (2016). Finnish reform of the funding and provision of special education: The views of principals and municipal education administrators. Educational Review, 68(2), 171–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2015.1060586

Qvortrup, A. & Qvortrup, L. (2018). Inclusion: Dimensions of inclusion in education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(7), 803-817. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1412506

Reindal, S. M. (2008). A social relational model of disability: A theoretical framework for special needs education? European Journal of Special Needs Education, 23(2), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856250801947812

Ruppar, A. L.; Neeper, L. & Dalsen, J. (2016). Special Education Teachers' Perceptions of Preparedness to Teach Students with Severe Disabilities. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 41(4), 273-286. https://doi.org/10.1177/1540796916672843

Saraisky, N. G. (2015). Analyzing public discourse: Using media content analysis to understand the policy processes. Current Issues in Comparative Education, 18(1), 26–41.

Schwab, S.; Holzinger, A.; Krammer, M.; Gebhartdt, M. & Hessels, M. G. P. (2015). Teaching practices and beliefs about inclusion of general and special needs teachers in Austria. Learning Disabilities, 13(2), 237-254. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2018.1516861

SOU 2008:109 En hållbar lärarutbildning [A sustainable teacher education]. Stockholm. Retrieved from www.regeringen.se

Stemler, S. (2001). An overview of content analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 7(17). Electronic Journal retrieved from http://PAREonline.net/getvn.asp?v=7&n=17.

Swedish Council for Higher Education. (2018). Anmälnings- och Studieavgifter [Announcement and study costs]. Retrieved from https://www.studera.nu/att-valja-utbildning/anmalan-och-antagning/anmalnings--och-studieavgifter/.

Swedish Higher Education Authority (2017). Higher education institutions. Retrieved from http://english.uka.se/facts-about-higher-education/higher-education-institutions-heis.html.

Swedish National Agency for Education (2017). This is the Swedish National Agency for Education. Retrieved from https://www.skolverket.se/om-skolverket/andra-sprak/in-english.

Takala, M. & Ahl, A. 2014. Special Education in Swedish and Finnish schools -Seeing the Forest or the Trees? British Journal of Special Education, 41 (1), 59-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2011.654333

Takala, M., Pirttimaa, R. & Törmänen, M. 2009. Inclusive special education: the role of special education teachers in Finland. British Journal of Special Education, 36 (3), 162-173. https://doi-org.www.bibproxy.du.se/10.1111/j.1467-8578.2009.00432.x.

Thomazet, S. (2009). From integration to inclusive education: Does changing the terms improve practice? International Journal of Inclusive Education, 13(6), 553–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110801923476

UNESCO. (1994). The Salamanca statement and framework for action on special needs education. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/education/pdf/SALAMA_E.PDF.

University Education. (2018). Yliopistot ja korkeakoulut [Universities and high schools]. Retrieved from https://www.yliopistokoulutus.fi/Yliopistot_ja_korkeakoulut__d3642.html.

University of Eastern Finland. (2017). Certificate program for special education teachers. Retrieved from http://www.uef.fi/web/kapsy/erityispedagogiikka/erilliset-erityisopettajan-opinnot.

University of Gothenburg. (2016). Special teacher education. Retrieved from http://ips.gu.se/utbildning/lararutbildning/speciallararprogrammet.

University of Helsinki. (2017). Studies for special education teachers. Retrieved from https://www.helsinki.fi/en/studying/how-to-apply/non-degree-programmes-for-teacher-qualifications.

University of Jyväskylä. (2017). Special teacher education. Retrieved from https://www.jyu.fi/edu/laitokset/eri/opiskelu/paaineopiskelijat/opetussuunnitelmat-ja-ohjelmat/ops-2014-2017.

University of Karlstad (2016). Special teacher education. Retrieved from https://www.kau.se/utbildning/program-och-kurser/program/LASPE-UTVS.

University of Linköping. (2016). Special teacher education. Retrieved from https://liu.se/utbildning/program/l9lsl.

University of Linneaus. (2016). Special teacher education. Retrieved from https://lnu.se/program/speciallararutbildning-ingar-i-lararlyftet-ii/specialisering-mot-sprak-skriv-och-lasutveckling-vaxjo-distans-deltid-ht/.

University of Oulu. (2017). Structure of special teacher education. Retrieved from http://www.oulu.fi/sites/default/files/content/Erityisopettajaopintojen_rakenne_lukuvuonna_2017-2018.pdf

University of Stockholm. (2017). Special teacher education. Retrieved from http://www.specped.su.se/utbildning/alla-program-kurser/speciallärarprogram/speciallärarprogrammet-90-hp-1.59815

University of Turku. (2017). Special teacher education. Retrieved from https://nettiopsu.utu.fi/opas/opintoKokonaisuus.htm?rid=26607&uiLang=fi&lang=fi&lvv=2016.

University of Vasa. (2017). Special education teacher studies. Retrieved from http://www.abo.fi/fakultet/studier_spi.

University of Umeå. (2016). Special teacher education. Retrieved from http://www.umu.se/sok/sok-utbildningsplan/utbildningsplan?id=147.

University of Uppsala. (2017). Special teacher education. Retrieved from https://www.uu.se/utbildning/utbildningar/selma/program/?pKod=USL2Y.

Uusitalo-Malmivaara, L. (Ed.). (2015). Positiivisen psykologian voima [The strength of positive psychology]. Bookwell: Juva.

Vitikka, E., Salminen, J., & Annevirta, T. (2012). Opetussuunnitelma opettajankoulutuksessa. Opetussuunnitelman käsittely opettajankoulutusten opetussuunnitelmissa. Tilannekatsaus 2012. [Curriculum in teacher education: Dealing with curriculum in teacher education]. Situation report 2012. Memorandum 2012: 4.

Von Ahlefeldt Nisser, D. (2014). Specialpedagogers och speciallärares olika roller och uppdrag – skilda föreställningar möts och möter en pedagogisk praktik. [Different roles and assignments of special educators and special teachers: Different performances meet and meet an educational internship] Nordic Studies in Education, 34(4), 246–264. Retrieved from http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A723034&dswid=-510

Watkins, A., & Donnelly, V. (2014). Core values as the basis for teacher education for inclusion. Global Education Review, 1(1), 76-92. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1055223.pdf

Waitoller, F. R. & Kozleski, E. B. (2015). No Stone Left Unturned: Exploring the Convergence of New Capitalism in Inclusive Education in the U.S. Education policy analysis archives, 23(37), 1-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v23.1779

Webb, R. Vulliamy, G.; Hämäläinen, S.; Sarja, A.; Kimonen, E. & Nevelainen, R. (2004). A comparative analysis of primary teacher professionalism in England and Finland. Comparative Education, 40(1), 83-108. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305006042000184890

Wiborg, S. (2013). Neo-Liberalism and Universal State Education: The Cases of Denmark, Norway and Sweden 1980-2011. Comparative Education, 49(4), 407-423. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2012.700436

Xin, J. F.; Accardo, A. L.; Shuff, M.; Cormier, M. & Doorman, D. (2016). Integrating Global Content Into Special Education Teacher Preparation Programs. Teacher Education and Special Education, 39(3) 165–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406416631124

YLE (Finnish Broadcasting Company) (2015). Yksityiskoulu vai tavallinen koulu? [Private or ordinary school?]. Retrieved from https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-6302305.