NJCIE 2018, Vol. 2(4), 53–69

http://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.2762

Appraising the Ingredients of the Interpreter/researcher Relationship: A Reflexive Qualitative Exploration

[1] Supriya Baily

Associate Professor, George Mason University, United States

Copyright the author

Peer-reviewed article; received 22 May 2018; accepted 01 August 2018

Abstract

The interview remains a highly powerful and valued method of data collection. Oftentimes, in cross-language studies, at the nexus of the interview between the researcher and the participant lies a critical third component: the translator or the interpreter. The relationship between the researcher and participant, especially in the construction of critical studies on voice and agency, depend on the relationship both the researcher and participant have with the interpreter. How does that relationship affect the “translation” of voice in a study? What are the ethical and linguistic considerations that need to be made in order to ensure a methodological fidelity? Using data collected with participants in rural India and Indonesia with the support of interpreters, this paper provides a lens through which a critical third participant plays a vital role in the voice and power of academic research.

Keywords: qualitative research; interviews; reflexivity; translators; interpreters

Introduction

The presence of interpreters or translators[2] is often critical in conducting comparative and international education (CIE) research. While researchers might be fluent in the languages of their participants, oftentimes, in situations where language expertise or regional dialect differences might cause a researcher to feel less than confident, an interpreter might be brought in to assist in the data collection process. This article seeks to make more visible the complexity of working with interpreters in an attempt to present a more robust picture of the impact these individuals might have on the research process. Working with two interpreters in India and Indonesia for data collection trips that have run into multiple weeks over multiple years, I was curious to better understand how their presence might have affected my overall research process. Using the tenets of basic qualitative design (Maxwell, 2013), I undertook a systematic review of my documented experiences to shed light on the role two interpreters had in my work. Partnering with Geetha in India and Putra[3] in Indonesia has raised questions on preparations in methodological practices as CIE researchers, the importance of addressing the impact such partners have had on presentation of research findings, and the overall transparency of bias, positionality, and reflexivity in CIE research.

As early as 1986, Briggs was suggesting that 90% of social science studies use interviews in some capacity to collect data (Briggs, 1986). One can confidently still say that the interview remains a highly powerful and valued method of data collection, particularly in qualitative inquiries. The interview remains a “special conversation” (Holstein & Gubrium, 2003, p. 3) where the emerging language helps the researcher make meaning within that particular context (Asay & Hennon, 1999; Miles & Huberman, 1994). Furthermore, making meaning takes on a greater sense of complexity in the more global landscape of qualitative research where there are increasing pressures to ensure diversity in representation in research and scholarship (Poland, 2003) and to especially challenge historic notions of the “white privileged researcher and the non-white weak respondents” (Kim, 2012, p. 133).

Researchers might often take on the role of a translator or interpreter, but the focus of this article is to understand how the presence of a third person affects the research process. Squires (2009) finds that researchers often “render” interpreter relationships invisible in the research process (p. 282), and can often misrepresent their own competence with the language, causing readers to make incorrect assumptions about both the methodologies presented and the findings documented. Noticing the limited training we have as researchers in working with interpreters, my own experiences in conducting research in multiple languages, and the importance of these relationships with those working with me, this article seeks to expose patterns and themes to shed light for those who are struggling to better manage and strengthen these relationships.

Theoretical framework

Literature on the selection, role, and impact of translators and interpreters are well grounded in the study of nursing (Baird, 2011; Fryer, Mackintosh, Stanley, & Crichton, 2012; Jones & Boyle, 2011; Morales & Hanson, 2005; Shimpuku & Norr, 2012; Squires, 2009). In education research, Qualitative Research has published a selection of articles over the past decade focusing on translation dilemmas (Temple & Young, 2004), assessing the validity of translator interviews (Williamson et al., 2011), and researching within ones own community (Kim, 2012). While there have been guidelines to approach the selection of translators and interpreters in a thoughtful and thorough manner (Poland, 2003), there has been a sense in predominantly positivist paradigms to “control for the ‘effects’ of the interpreter/translator, to treat them as a threat to validity, and to make them invisible in the process and product” (Berman & Tyyskä, 2010 p. 179). Nevertheless, as research projects continue to grow across, beyond, and within borders of all fashions, the use of such facilitators will not end, requiring us to look within ourselves as researchers to ask in what ways do these relationships shift, alter or impact the dynamics of our qualitative inquiry?

My own curiosity on this stems from my ontological position as a critical feminist researcher and the importance of voice and agency in the research process. As a researcher, my agenda has focused on gender and education and deconstructing notions of empowerment and agency. I have spent time in the field in both rural south India and rural Indonesia, immersing myself in the lives and experiences in two villages and in both cases working with interpreters. In India, I worked in the southern peninsula, where I speak one of the four major regional languages. But I still required an interpreter to ensure limited loss of meaning with dialect shifts and more nuanced understanding of potentially complex ideas. In Indonesia, I spoke absolutely no Balinese and therefore required the assistance of an interpreter for all the data collection work.

While this article takes a reflexive approach, the theoretical framework is built on the two domains of literature: engagement within the interview process and the attributes of a seasoned translator. It is also important to distinguish between the interpreter and the translator. Baird (2011) describes the translator as one who, in her study, translates written material into English, and the interpreter as one who has direct contact with participants. Jones and Boyle (2011) also maintain the same distinction where translators work with written text and interpreters translate spoken language. In this study, I will maintain the same distinctions, with one critical difference. The people I worked with acted as both translators and interpreters, but I will call them interpreters, as that was the first role they played in our efforts together. I will also use the term “research team” to address the presence of both the researcher and interpreter in the context of that moment.

Engagement in the research process

The role of interviewing is a dynamic process, which requires language skills as well as a battery of other physical, social and cultural attributes that are both observable and innate. The ways in which the research team interact with each other and the ways in which they engage with the participants must show evidence of trust and transparency, among other skills. When language is the foundation of data collection in qualitative research through the interview process, there is an extra layer of complexity that exists, especially as it relates to issues of trust and quality (Fryer et al., 2012). If the interviews “vary from highly structured, standardized, survey interviews, to semi-formal guided conversations, to free-flowing informational exchanges” (Holstein & Gubrium, 2003, p. 3), the role of the interviewer requires skills that are relative to and dependent on the context and expectations of the interviews. Gathering information from interviews also depends on the relationships that are embedded within the structure of the interview, namely the relationship between the “researcher and the interpreter and between the interpreter and the participants” (Baird, 2011, p. 21). While the research team must be able to illustrate their comfort with each other, the bond between the researcher and the interpreter is critical for success in the interview processes with participants. Baird (2011) goes on to suggest that the respect that underlies the interpreter’s relationship with the participants is critical for the study to be successful. The willingness of participants and the “depth of information they were willing to share” (Baird, 2011, p. 21) are enhanced by the positive engagement that occurs within these relationships.

Mayorga-Gallo and Hordge-Freeman (2016) speak of credibility and approachability as viewed by participants; especially in what might be seen as multiethnic or “multiplex field experiences” (p. 2). Credibility is defined as the ability to establish “oneself as a worthwhile investment of time for the respondents” (p. 5), and approachability is viewed where the “researcher is non-threatening and safe” (p.5). Both of these traits are reflected in how the respondent views the researcher and the ways, performed and perceived; in which trust, openness, and familiarity are translated to the person being interviewed. While Mayorga-Gallo and Hordge-Freeman (2016) operationalize the traits to highlight aspects of both performance and perception such as cultural credibility, support of key informants, and being seen as easy to talk to; in the case of working with an interpreter, these operationalizations would need to be doubled—that is, both the researcher and the interpreter would need to showcase credibility and approachability in order to make headway in the interview process.

Engagement with language as central to the role of the research team’s work to collect data must also be examined. While language itself takes on a multifaceted approach in the interview process, critical issues to keep in mind include the ways in which word usage and meanings incorporate certain in-group values and beliefs (Fryer et al., 2012) and include “idiosyncratic meanings as well as humor, and references to political and societal events” (Asay & Hennon, 1999, p. 412). As Asay and Hennon (1999) also discovered with U.S. researchers locating their work in Scotland, this can occur even in spaces where there is commonality in language, but difference in meaning

In addition, one issue to consistently identify is how engagement in the research process between researcher/translator/participant is one of power and power relationships. The research process is inherently about power dynamics where the researcher often benefits most directly (Larkin, Dierckx de Casterlé, & Schotsmans, 2007). One way that researchers have tried to mitigate these power relations is to identify local partners who are co-researchers, but as Wong and Poon (2010) found with their partners in Canada, the label did not change the fact that the local partners were still used as if they were graduate assistants, were provided limited training, and were called upon too frequently to help. Other concerns related to interpretation and power include the relatively quick translation of the data into the dominant language (usually English) (Temple & Young, 2004) and the assumptions of readers where they are unaware of the role of interpreters in such research projects and as such are unaware of the layer between the researcher and the participant that might alter the understanding, nuance, and sometimes even meaning of the language (Squires, 2009).

Attributes of the seasoned interpreter

The attributes of a seasoned translator include a variety of optimal behaviors and dispositions. As mentioned earlier, humor, social events, and idioms of language are important to navigate in interviews (Asay & Hennon, 1999). It is also important for a seasoned interpreter to have the capacity to both exhibit and recognize these nuances in conversations. Berman and Tyyskä (2010) focus on the familiarity of the translator to both the researcher and the participants in order to provide detailed and more nuanced understandings not just of what is said, but oftentimes the meaning behind the words as well. Baird (2011) goes much further, asking for formal training in interpretation, appreciation for research ethics, and familiarity with protocols.

Social and cultural considerations include attributes that ensure trustworthiness and credibility between the participants and the research team. The lived experiences of the researcher and participant will never be completely similar, and differences in age, gender, life experience, and occupation are as much cross-cultural domains as ethnicity, cultural affiliations, or national/religious identity. Wong and Poon (2010) articulates that the contestation of culture allows for multiple interpretations as a “system of dynamic, ambiguous, and conflicting meanings, intertwined with language and discourse, mediated by power” (p. 152), and as such the use of interpreters adds another facet that requires further exploration in the interview process. As we seek to ensure representation of a broad range of participants, the crossing of many cultures becomes more evident in the interview process with the addition of the interpreter to the mix.

In a perfect research project, many of these attributes are visible and are brought forth to bear on the research process. Yet, challenges include expediency of hiring an interpreter, comfort with the language (Jones & Boyle, 2011), and potential availability during the time the research is going to be undertaken. These attributes may merely scratch the surface for a seasoned interpreter. More sophisticated attributes could be the relationship between the interpreter and the participants, early language development, and mimicking the social and educational background between the interpreter and researcher (Jones & Boyle, 2011). Further concerns might include the levels of trust the participants have with the translator (Baird, 2011), but then this would require the researcher to more closely navigate the status of insider/outsider, insider/insider, and outsider/outsider between the three main players in the research process—participant, interpreter, and translator.

While researchers have tried to systematize how researchers and interpreters work together (Berman & Tyyskä, 2010), what has been lacking in the literature is specific explorations of how these relationships unfold. More specifically, scholars have written about how issues of power (Berman & Tyyskä, 2010), linguistic ability (Baird, 2011), cross-cultural comfort (Temple & Edwards, 2002), and understanding of research process and relationships (Soni-Sinha, 2008), could impinge on the research process—we are still unclear on how such abstract concerns play out in actual research experiences. What do researchers and interpreters work together to achieve? How does power and knowledge of the research process hinder or help the interpreter and researcher accomplish what they set out to do? What happens when everyday complications enter the research process? Having worked with two very different interpreters in two unique contexts and keeping extensive notes on the relationship, this paper provides a more complex understanding of the reflexivity at play between both parties.

Methodology

Finlay’s (2002) approach to understanding these relationships draws attention to both the reflexivity and positionality of the study to:

Examine the impact of the position, perspective, and presence of the researcher; promote rich insight through examining personal responses and interpersonal dynamics; empower others by opening up a more radical consciousness; evaluate the research process, method, and outcomes; and enable public scrutiny of the integrity of the research through offering a methodological log of research decisions. (Finlay, 2002, p. 532).

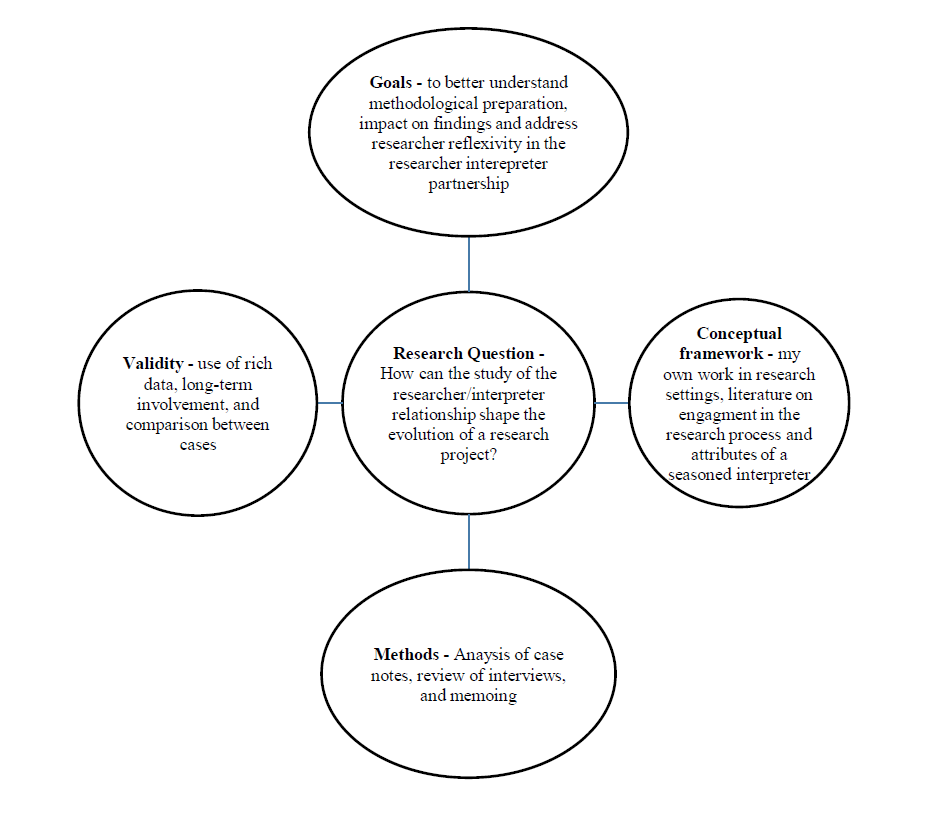

For such an examination, the use of Maxwell’s (2013) basic qualitative design is the most useful method through which to understand how the goals, conceptual framework, research questions, methods, and validity are linked in this study.

Figure 1: Maxwell’s conception of basic qualitative design for this study

(Maxwell, 2013)

The broad research question emerged out of my own curiosity and takes an auto-ethnographic approach to study my own prior experiences. Going back to my field notes, I selected 15 days of field notes from each site to analyse, listened again to the recordings of the interviews we conducted, and began to situate our partnership in the larger context of the research. My field visits occurred in 2007, 2011, and 2013. Reflecting on the role of the interpreters, Geetha and Putra[4], I realized that their impact on the research conducted went beyond the role of mere interpreter and translator of language. In the day-to-day struggle of conducting field research, the conversations we had privately, the missteps we made publicly, and the private notes I made during our time in the field offered a chance to think more critically and conceptually on their role in the research process.

Geetha is a female, in her late fifties with a long history of social activism and a deep and abiding love for the state we were conducting research in. With a history of civil service as a daughter and military service as a wife, she has a family and a job as an educational consultant. Putra is a young man in his early twenties, also with a history of social activism. His family is from the village which was the site of the research project. Both came suggested to me through a network of professional and personal acquaintances.

In the field, the researcher and translator are often their own island, and their interactions and ability to work productively occur in an intense period of time. In honor of the many meals we shared, each of the themes below emerged from a field note that referenced an aspect of a meal we partook together, two from the Indian notes, and two from the Indonesian notes. Each “diary entry” that precedes the section was created from a compilation of notes, transcripts, conversations, and memories from that day.

Key Moments in the Researcher/Interpreter Relationship

As this was such a personal endeavor, built on the study of self in a relationship with others, I would like to highlight that this article is an effort to engage researchers to think about the role of the interpreter more closely as they design and develop their research questions. Rather than addressing these as themes, these findings are connected more deeply to a reflexive approach to the process of working with and entering into professional and research relationships with a critical third party in the otherwise traditional dyad of research relationships. These understandings are grounded through the metaphor of the meals that were shared between the researcher and the interpreter covering the complexity of working with each other; delving into commonalities; handling stressors and distractions; and finally breaking down the third wall between the professional and personal.

Bonding over fried sweet neem leaves

Geetha and I have arrived. The anticipation of what work I have before me is daunting for sure and it didn’t help today with the taxi driver leaving us stranded at the restaurant and running back to the city with everything—but especially the consent forms…What was he thinking? But the papers are back with the new driver—so hopefully all will be well. It did give Geetha and myself a chance to see what we were like under pressure—I think we will make a good team but let’s see what it is like for the next three weeks—it is not easy for me sharing space with someone day after day. At least we will be well fed—I loved the place we got lunch today (in spite of the runaway driver)—the fried neem leaves were AMAZING! Can’t imagine I grew up 50 km from here and have never had them before. She hadn’t either—isn’t that odd? And it’s supposed to be a staple?

While the research team must show a level of comfort and trust with each other, in most cases, the researcher and the interpreter are new to each other as well. In both the Indian and Indonesian studies, the interpreters and I met just a few days before the data collection was set to begin. In both cases, the getting-to-know-you process occurred in a complex space of being engaged in an employer/employee relationship and organizing the logistics of the time spent collecting data. In Geetha’s case, we were also sharing a room for the duration of the data collection, which meant we were together for three weeks almost every minute of every day. For the data collection process to be robust, it required that we got along, engaged in a friendly manner with each other, and were able to present a unified front to our participants.

Our experience with the lost driver is emblematic of the unknown and unprepared challenges that occur in the field. While at lunch, our driver, who was missing the comforts of home after being away for approximately eight hours, drove off from the restaurant and got on the highway back to the city, some four hours away. He left with all the tape recording equipment, consent forms, and other field-based paraphernalia we needed to begin our work. While we were able to phone the taxi company and have a new driver intercept him on the highway to recover the items. It was a tense situation and required both of us to maintain our composure.

Researchers can anticipate as many challenges and crises in the data collection process, but until you are in the field, you cannot plan for random acts of spontaneity or unimaginable actions of others. When the driver left us without the tools to embark on the work, we had to adjust to figure out a plan in a place that neither of us had resources or contacts. What we quickly discovered was that we had compatible personalities and an attitude that split up decisions to move forward. I got on the phone with the car rental company to figure out how to intercept the driver to retrieve the research items, and Geetha began conversations with the restaurant owner to identify a local car company to hire a local driver. In this way, we divided, conquered and moved on. What might have been an inauspicious start to the research trip became instead a common adventure that we bonded over.

Negotiating our commonalities over Sambal

Things are getting easier—the village is small and the people seem used to Putra and myself walking around shooing the dogs that follow us incessantly. There is no silent approach anywhere until the dogs accept me as one of the locals, and my hope is that it will happen soon! Our days have an easy pace to them, early mornings to mid-afternoon, walking around, chatting, being invited into homes, and sitting, eating jackfruit, talking to the women and men. Then we leave and head to town for lunch. Today’s interviews were draining to listen to—and I like that Putra and I were able to spend some time talking about what we hear when we have lunch. He definitely has an opinion on what we are hearing – but I think that we are seeing the same things, which is good. After debriefing, we focus on lunch and devour the rice, chicken, vegetables, hard-boiled egg, and one of the 10,000 sambals (chili sauces) we will get today.

With Geetha, there was much that we shared that seemed obvious. We were both women; mothers (which almost always provided my participants a sense of trust, comfort, and a belief in my overall stability); and we spoke the same mother tongue. Traveling in remote regions with another woman was a safe approach to take and did not raise eyebrows in relatively traditional situations. In Indonesia, my translator was a young, single, independent man who was from the village, and our connection was that his aunt was a colleague of mine at the university. I had absolutely no knowledge of the local language and would be spending hours every day with someone who I would initially need to trust explicitly.

While reflection and caution are important to researchers in such contexts, I found that our commonalities emerged immediately. Among the many unexpected commonalities that emerged between the “Indian Hindu” as I was often introduced to participants in the field, and my “Balinese Hindu” translator, Putra (though neither of us identified religion as an important intersection), was our love for the chili sauces. Enjoying the sambals brought Putra and myself closer to each other and offered us a casual and unique platform through which we are able to have robust discussions about the conversations we were having on a daily basis with people in the close by village.

It was this ritual of time spent daily, breaking bread together that allowed for Putra and I to understand each other’s motivations and the overall deeper goals of the project. It is often impossible to share a common understanding of anything because the interpretation of the questions, ideas, data, and analysis all utilize language that can never be interpreted in exactly the same way by different people with different experiences. Yet, these lengthy conversations and time spent every day, reflecting on what we heard, how we understood what we heard, and what might be relevant follow up questions that were triangulated between what the interviewer needed, the interpreter heard, and the respondent shared helped build a more cohesive understanding of the meaning of the words. This became especially important in moments of dissonance or miscommunication as I share in the next section.

Choosing not to drink the buffalo cow buttermilk

The pace in a village has an even keel after our first 48 hours where we seemed more disruptive. We get settled in the morning in the community hall, drink our tea, chat with the women who are doing the community accounts, and then start our interviews. After a couple of hours, we head out to walk around the village, pop into school during their recess, talk to the teachers, and then walk back to the community hall. It is usually at this moment, one of the village women will bring us some afternoon buffalo cow buttermilk to keep us going until lunch. Every day they bring two glasses and every day Geetha refuses to drink it because it just doesn’t appeal to her. This causes some tension for me and annoyance for the woman who brings it to her. Even when we say we don’t want them to trouble themselves, the hospitality of the village demands they offer and—our presence demands we drink.

While the translator and the researcher try their best to be a team, there are often moments of tension and discord. These moments are to be expected due to the close proximity and physical and emotional strain that emerges when one works in multiple languages and on sensitive topics for weeks at a time. In addition, the more connected the interpreter is to the research topic, usually allows them to bring forth their own interests and questions, also affecting the interview process. While in both these situations, the interviews were semi-structured, with a substantive time for introductions and general questions, the gist of the conversations intersected with Geetha and Putra’s own interests as activists and locals.

A few times, I could hear in Geetha’s voice that she wanted to take the interview into a place that was interesting for her. She would get caught up in the conversations that especially centered on local politics and would start to divert the questions and conversation into something that was her passion or interest. Knowing enough of the language meant that I could jump in and guide the conversation back to where it needed to go. The data was rich, and the conversations thoughtful, and as an individual engaging in that process, it would be hard to resist asking follow-up questions. But these side conversations risked us losing our participant to time constraints or to shifting momentum on issues that were directly related to the research project.

We often heard the same ideas as we listened to our participants, but we also learned to recognize that we had different agendas. With Putra, his activism was central to his identity. He spent much of his time organizing movements, engaged in social action projects and worked with many marginalized and disenfranchised youth on the islands. This stance ensured that he had a fluent understanding of the issues related to microcredit, agency, and empowerment that were the focus of the research project. He also enjoyed actively engaging in the interview process. Initially, the interviews highlighted divergences focusing on conversations that were peripheral or unrelated to the research topic. It was always clear when this happened. The tone of voice got more excited, the conversation flew back and forth between the participants, and the translations and responses back to me were more of a synopsis than a full explanation. This also happened with Geetha, but in that case, I had a strong knowledge of the language, so it was easier for me to bring the conversation back to the original idea, but with Putra, it required more caution and tact.

Again, in the daily conversations I had with both, with Geetha in the nights as we prepared for dinner and bed, or with Putra and our lunch hour conversations trying a new sambal every day, we were able to go deeper into the conversations that he might have diverted to over the course of the interviews. In fact, what might have been seen as initially a problem for the research process, turned into something that was providing a value for both parties. Over time, I was able to realize that the structure of the conversation allowed Putra to ensure he had first hand knowledge of the injustices he saw occurring in the village and allowed the research process to be helpful both at the researcher level, but hopefully for the village at some point as well. Due to the types of work both Geetha and Putra do during the rest of the year, and Putra’s relationship to the village, it would appear that the term “interpreter” that I used might have been further adapted to be more illustrative of the role they played in the research process.

Learning to relish fried chicken blood

It is definitely interesting spending your birthday in the field. Both Putra and Indra (the driver) started the day off so well. I can’t believe they went to the market to get me presents—but the real delight was the lunch. The whole family came out and we sat in the veranda enjoying the good smells that lunch would bring, chatting and laughing. After this much time together, you would think we were always going to be together. Coming to the lunch table, as the guest of honor, I took a little of everything. Putra told his mother a couple of times “she doesn’t eat a lot of meat, so don’t force her” but it was my birthday and they were going through a lot of trouble—how could I not try everything? Then Putra’s father said, “try the crunchy’s on your rice, very good for cholesterol”. The others laughed as I served myself, and Putra’s mom tells me cheerfully “The fried chicken blood is our specialty.”

Part of the process of data collection in contexts that are not our own is that we rely on local expertise to guide us through the complexity of relationships, especially to ensure that local traditions, beliefs, and customs are not ignored. Planning for challenges in collecting data in rural and remote regions of the world is something most researchers consider; yet what often happens is that the isolation one plans for is often not accurate. While you maintain a professional distance from participants, the routines you establish in the field build new relationships. Whether it is the people who live near or where you stay, the places you frequent to eat, to get a cup of tea, or where you might make photocopies or seek out free internet, become your new community. Finally, the challenges that I experienced, with missing consent forms, talking to women about critical and oftentimes sad experiences, as well as spending milestone moments overseas, meant that the relationships with interpreters became one of friendship.

In some ways, as the relationship between the researcher and interpreter deepens, there are added benefits to the research process. What the fried chicken blood offers in this analysis is the recognition that the researcher is out of their comfort zone, and in bridging differences between you and the interpreter, it allows for some balance in the otherwise strong power differential between the two of you as employer/employee. While the hospitality extended on Putra’s side, was a privilege I was able to enjoy, it allowed us to have moments that were not work related and see each other in more human terms. In engaging with Geetha back in the city, and meeting family, we were able to have conversations that deepened the relationship, and added to the analysis of the projects to be further reminded of their active engagement in the research process.

Discussion

At the onset of this article, I surmised that without a deeper understanding of the researcher/interpreter relationship, there might be unforeseen ramifications on our preparation as methodologists; the impact of our findings; and the overall transparency of bias, positionality, and reflexivity in CIE research. I also asked the questions: What do researchers and interpreters work together to achieve? How does power and knowledge of the research process hinder or help the interpreter and researcher accomplish what they set out to do? What happens when everyday complications enter the research process? I do not have answers to these questions, but based on my analysis of my own experiences, I seek to provide some food for thought.

So what do we work together to achieve? What I did find is that there is greater dependence on the interpreter than one might foresee. Literature speaks to the invisibility of interpreters and translators (Edwards, 1998; Turner, 2010), and the overall power held by the researcher in the relationship. Turner (2010) also highlights cases where researchers would try to avoid deepening relationships in an effort to maintain distance in the relationship between employer and employee. I found that the more we interacted as individuals, the more our rapport in the field improved, and the greater our willingness to push each other to clarify thinking and avoid a more formal and distant engagement in the research process. The relationship is bolstered when the researcher works to share the significance of the research topic, the aims of the study and the ethics of conducting research with the interpreter as well (Edwards, 1998).

As a faculty member who teaches research methods, supervises methodologies for dissertations, and as a consumer and reviewer of research, I find that researchers spend limited if any time on preparing to work with the interpreter. Those who have written about the researcher/interpreter relationship have highlighted the need for a high quality relationship as critical to the research process (Baird, 2011), but the focus tends to remain on the levels of trust between the researcher and the respondents, ignoring the role of the interpreter in the center of that chain. Berman and Tyyskä (2010) cite the work of Shklarov on the “double role” of the interpreter who can both provide first hand knowledge of the local community, as well as protect the interests of the respondents while also helping to maintain “research integrity” (p. 181). Understanding the intent of the study (Baird, 2011) provides the researcher a more effective partner who can “accurately explain them to participants and interpret their responses back to the researcher” (p. 2). While the concerns of having interpreters engage in their own interests in the conversations with participants might have to be addressed, the fostering of a relationship overall, in my analysis, provided a more nuanced view of the data from the two perspectives.

Ryen (2003) argues that to ensure validity “words and concepts be interpreted in the same ways by interviewers, interpreters, and respondents” (p. 438). This idea is reiterated in the work of Larkin et al. (2007) who argue that “we meet the world…through conversation” (p. 474), and that the “ability to share ideas with people…was extremely valuable in helping us…feel secure in the tools for research, but also to know that the translators understood the perspectives and values of the research process” (p. 474). The need to be explicit about the collaboration with the interpreter and with the reader can help to ensure that there is greater transparency in how the findings are presented in the final product.

My second question asks: How does power and knowledge of the research process hinder or help the interpreter and researcher accomplish what they set out to do? Vara and Patel (2012) find that issues of power are “salient throughout the research process” (p. 79). This saliency is exhibited not just in traditional notions of the exertion of power over by the researcher, but Vara and Patel (2012) argue there is power in triadic relationship, the power of supervision of the researcher over the interpreter, as well as the power interpretation. The relative presence of power in multiple phases and activities in the research process is not always shared clearly with the reader in a reflexive and reflective way. While a considerable amount of time spent in preparing novice researchers is dedicated to discussing their own reflexivity where the consideration of a researcher’s perspective takes into account “a researcher’s position…(relating to) power relationships between the researcher and the researched, a researcher’s insider and outsider position, and modes of representation and translation” (Kim, 2012, p. 132), there are seldom references in studies with interpreters that makes those reflexivities transparent.

Researchers share their own tensions of identification in the research process. Ghaffar-Kucher (2014) talks extensively about the crisis of representation in qualitative research where the researcher must question: their place as an insider; the presence of the research as “politically charged or hyper-resent in public discourse” (p. 3); and the representation the researcher has with the reader as an insider and therefore more capable of representing the community. These notions of authenticity and positionality can lead to problematic assumptions and can be extrapolated through the curtain between which the research team navigates their own understanding of authenticity and positionality. In some ways, the presence of the interpreter in both of my situations provided the respondents a way to determine what parts of my identity they preferred to speak to—whether it was being a mother in India, or an Indian-Hindu in the Balinese context. The time that the research team spent getting to know each other allowed for the interpreter, who could also be seen as a gatekeeper, to determine what aspects of my own identity resonated with them.

This idea of insider-outsider is illustrated by Kim’s (2012) article determining the use of language depending on who is writing, whom the audience is, and the context of what is being written. Saying that “translation is a matter of reflexivity” (p.141), Kim (2012) posits that the use of immigrant versus emigrant in his study on the Korean diaspora would, in fact, provide clues related to his own “sociocultural positioning” (p. 141). Researcher reflexivity would be stated in high quality studies, but the fact remains that oftentimes the interpreters’ reflexivity is unnamed and unshared with the researcher or the reader. The use of a seasoned interpreter might present a clearer picture of the layers of linguistic, cultural, social, economic, and political translation that occurs in this relationship between researcher, interpreter, and participant.

Finally, I ask: What happens when everyday complications enter the research process? This is a guarantee and we would do well to remind novice researchers that a Plan B must be in place, but we do have to trust the partnership we are developing with the interpreter for they are more than a conduit through which language is exchanged. Researchers are taught to “not provide answers or offer opinions” (Holstein & Gubrium, 2003, p. 19), yet cannot often, or should not always, follow this rule. Furthermore, interpreters who have their own interests and are oftentimes locally engaged, might not be able to help themselves from engaging more actively in the discussion. In the daily conversations, we were able to go deeper into the conversations that the interpreters might have diverted to over the course of the interviews. In fact, what might have been seen as initially a problem for the research process, turned into something that was provided value for both parties. While collaboration has been narrowly defined as co-research partners (Pryor, Kuupole, Kutor, Dunne, & Adu-Yeboah, 2009), in the context of these studies, the time spent and conversations that occurred with the interpreters was a form of collaboration that has never adequately made it into the culminating research products. Taking their word on local matters, trusting their methodological decisions on participant selection and interview details require ensuring there is an “us in trust” (Edwards, 2012, p. 511).

The more the triadic relationship seeks to be “egalitarian…with a commitment by the researcher to being transparent” (Vara & Patel, 2013, p. 80) was key to the success of the partnerships exhibited through the richness of data collected. Over time, I was able to realize that the structure of the conversation allowed both Geetha and Putra to ensure they had first hand knowledge of the issues in the village and allowed the research process to be helpful both at the researcher level, but hopefully for the individuals in the villages at some point in the future as well due to the connection between the participants and the interpreters.

Berman and Tyyskä (2010) criticize the more one-dimensional term “translator” suggesting instead, “community researcher” “interpreter”, “cultural broker”, “key informant” or even “interpretive guide” (p. 184). Due to the types of work both Geetha and Putra do during the rest of the year, and Putra’s relationship to the village, it would appear that the term “interpreter” that I used might have been further adapted to be more illustrative of the role they played in the research process.

Conclusion

While both of these experiences, over multiple trips and over a span of multiple weeks, had challenges, the two individuals were of exemplary character, making the data collection easy, the research process positive, and the overall energy around the project successful. The importance of interpreter credentials, their awareness of different research approaches, and clarity on their role in the research process (Squires, 2009) should all be considered, but the ability to find mutual understanding, a fellowship of sorts with this individual cannot be stressed enough. Both the comfort and discomfort of building a new relationship with the interpreter is one that, without calculation or prior strategy, can, in fact, deepen and bring personal value to the research process.

Ryen (2003) documents how verbal and non-verbal communication can assist or hinder in the interview process, further highlighting the importance of context to build both rapport and understanding. Ryen (2003) provides numerous examples from researchers in India specifically those who navigate caste, class, and gender differences in an effort to collect data through interview. And while all those cases did not document the presence and participation of an interpreter, the reality is that the researcher must often go beyond the scope of the languages they speak in order to collect the data they need.

Yet, the interpreter becomes the windowpane, the glass, which is often ignored but can have a dramatic effort on the view. Kim (2012) defines reflexivity as a tool, which allows for an examination of the “position, power, and presence of the researcher”; the promotion of “rich insights by examining personal responses and interpersonal dynamics”; and the option of “public scrutiny of the integrity of research by offering a methodological log of research decisions” (p. 144), the presence of an interpreter cannot remain invisible in this process. The presence of the interpreter is an ever-present lens through which the researcher and the participants’ voices are framed.

The role of the interpreter cannot be overstated, nor is it one that is to be ignored in a positivist haze of controlling for variables. Just as reality is constructed in the analysis process, the researcher and interpreter are co-constructing a lived experience through which they will together collect data in an effort to shed meaning on a research question. This co-constructed reality, where two people are expected to trust, work collaboratively and have a mutual understanding of the research procedures and outcomes, can affect the research process. The experiences I had with my interpreters brought to light the need to be prepared for unforeseen challenges, patience in light of the extended amount of time we spent together, and the need to learn who we were as people rather than just through the roles we played in the research process.

References

Asay, S. M., & Hennon, C. B. (1999). The challenge of conducting family research in international settings. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 27(4), 409–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077727X99274003

Baird, M. B. (2011). Lessons learned from translators and interpreters from the Dinka Tribe of Southern Sudan. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 22, 116–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659610395764

Berman, R. C., & Tyyskä, V. (2010). A critical reflection on the use of translators/interpreters in a qualitative cross-language research project. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1, 178–190.

Briggs, C. (1986). Learning how to ask. A socio-linguistic appraisal of the role of the interview in social science research. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139165990

Edwards, R. (1998). A critical examination of the use of interpreters in the qualitative research process. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 24, 197–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.1998.9976626

Fryer, C., Mackintosh, S., Stanley, M., & Crichton, J. (2012). Qualitative studies using in-depth interviews with older people from multiple language groups: Methodological systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(1), 22–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05719.x

Ghaffar-Kucher (2014). Writing culture; Inscribing lives: a reflective treatise on the burden of representation in native research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education.

Holstein, J. A., & Gubrium, J. F. (2003). Inside interviewing: New lenses, new concerns. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412984492

Jones, E. G., & Boyle, J. S. (2011). Working with translators and interpreters in research: Lessons learned. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 22(2), 109–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659610395767

Kim, Y. J. (2012). Ethnographer location and the politics of translation: Researching one’s own group in a host country. Qualitative Research, 12, 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111422032

Larkin, P. J., Dierckx de Casterlé, B., & Schotsmans, P. (2007). Multilingual translation issues in qualitative research: Reflections on a metaphorical process. Qualitative Health Research, 17(4), 468–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307299258

Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mayorga-Gallo, S., & Hordge-Freeman, E. (2016). Between marginality and privilege: Gaining access and navigating the field in multi-ethnic settings. Qualitative Research, 17(4), 377–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794116672915

Miles, M. B. & Huberman, A. M. (1994) Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Morales, A., & Hanson, W. E. (2005). Language brokering: An integrative review of the literature. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 27, 471–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986305281333

Poland, B. D. (2003). Transcription quality. In J. A. Holstein & J. F. Gubrium (Eds.), Inside interviewing: New lenses, new concerns (pp. 267–288). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Pryor, J., Kuupole, A., Kutor, N., Dunne, M., & Adu-Yeboah, C. (2009). Exploring the fault lines of cross-cultural collaborative research. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 39(6), 769-782 https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920903220130

Ryen, A. (2003). Cross-cultural interviewing. In J. A. Holstein & J. F. Gubrium (Eds.), Inside interviewing: New lenses, new concerns (pp. 429–448). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Shimpuku, Y., & Norr, K. F. (2012). Working with interpreters in cross-cultural qualitative research in the context of a developing country: Systematic literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(8), 1692–1706. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.05951.x

Soni-Sinha, U. (2008). Dynamics of the ‘field’: Multiple star narrative and shifting positionality in multi-sited research. Qualitative Research. 8, 515–537. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794108093898

Squires, A. (2009). Methodological challenges in cross-language qualitative research: A research review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46, 277–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.08.006

Temple, B., & Edwards, R. (2002). Interpreters/translators and cross-language research: Reflexivity and border crossings. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690200100201

Temple, B., & Young, A. (2004). Qualitative research and translation dilemmas. Qualitative Research, 4, 161–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794104044430

Turner, S. (2010). Research Note: The silenced assistant. Reflections of invisible interpreters and research assistants. Asia Pacific Viewpoint. 51, 206–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8373.2010.01425.x

Vara, R. & Patel, N. (2012). Working with interpreters in qualitative psychological research: Methodological and ethical issues. Qualitative Research in Psychology 9, 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2012.630830

Williamson, D. L., Choi, J., Charchuk, M., Rempel, G. R., Pitre, N., Breitkreuz, R., & Kushner, K. E. (2011). Interpreter-facilitated cross-language interviews: A research note. Qualitative Research, 11, 381–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111404319

Wong, J. P.-H, & Poon, M. K.-L. (2010). Bringing translation out of the shadows: Translation as an issue of methodological significance in cross-cultural qualitative research. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 21(2), 151–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659609357637