NJCIE 2019, Vol. 3(2), 3-19 http://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.3027

A Theoretical Approach to Understanding the Global/Local Nexus: The Adoption of an Institutional Logics Framework

Karen Parish[1]

Associate Professor, Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences

Abstract

This article takes as its starting point the theoretical debate within the field of Comparative and International Education surrounding the way in which the global/local nexus is understood and researched. Attempting to move the debate forward, the paper introduces the institutional logics approach as one way in which the global/local nexus can be explored. Institutional logics focus on how belief systems shape and are shaped by individuals and organisations. A framework, based on the institutional logics approach, is presented in this paper taking the phenomenon of human rights education as an illustration. The author proposes that by adopting an institutional logics approach and framework we can gain a better theoretical and empirical understanding of the global/local nexus and at the same time provide a much-needed bridge between the opposing views within this ongoing debate in the field of Comparative and International Education.

Keywords: institutional logics; global education; human rights education

Introduction

Education varies across time and nations and is constantly renegotiated by societal leaders as they address issues of governance, immigration and the socialisation of future citizens. Education is seen very much as a national project and as such studies of Comparative and International Education (CIE) have overwhelmingly focused on comparisons of this nature. However, the effects of globalisation on education systems have gained increasing attention as scholars seek to better understand the global/local nexus (Appadurai, 1996; Carney, 2009; Madsen, 2006; Meyer & Ramirez, 2000; Schriewer, 2015).

At a basic level, globalisation can be defined as the process by which countries and their citizens are increasingly drawn together, leading to the erosion of traditional modes of life and the advancement of standardisation and homogenisation into all areas, including education policy (Archard, 1996; Kasuya, 2001, p. 237). Further to this Wiseman (2010), a neo-institutional theorist, argues that the changing politics of nation-states caused by and enacted in the name of globalisation means that education systems are susceptible to internationalisation and are becoming convergent. This can be seen in policy borrowing, decision-making processes, administration and teaching within classrooms.[2]

Within the field of CIE, one strand of neo-institutional theory has developed the argument that a world culture is being disseminated globally through education systems (Wiseman, Astiz, & Baker, 2014). This is conceptualised within neo-institutional theory as ‘isomorphism’ – “a process of becoming similar in spite of conditions that would otherwise suggest diversity” (Wiseman et al., 2014, p. 698). The global human rights discourse is one aspect of this world culture that it is argued by some neo-institutional theorists is being disseminated through education systems, influencing shared expectations and norms for behaviours and legitimate activity (Boli & Thomas, 1999; Wiseman et al., 2014). It is important to note that proponents of world culture theory (WCT) do not claim that the process of becoming similar (isomorphism) is code for universal homogenisation or the endorsement of such a state of being (Wiseman & Chase-Mayoral, 2013). However, it is argued that WCT over-emphasises the impact of globalisation and critics of WCT have therefore “focused on the local enactment of world-level phenomena by highlighting the centrality of agency and the politics behind the implementation of global reforms in different national contexts” (Anderson-Levitt, 2003; Carney, Rappleye, & Silova, 2012; Schriewer, 2012; Steiner-Khamsi, 2004). In so doing they risk overlooking the explanatory power that neo-institutional theory can bring to this discussion.

What has emerged within the academic community is something of a standoff between proponents of a converging world culture within education and their detractors. Attempts have been made to bridge the gap between the opposing views and approaches. A good example of this is the volume edited by Schriewer (2015) that draws together scholars from different areas of the discussion. Schriewer (2015, p. 1) makes the point that unlike in the social sciences, within the discipline of globalisation and education, theory remains “implicit, theoretically unexplained” and laden with “normative undertones”. The exception to this is the work of proponents of WCT whose work within the discipline of education has met “epistemic expectations” directed towards social theory (Schriewer, 2015, p. 1). Schriewer (2015) therefore sets out to both acknowledge the contribution of WCT and move the discussion beyond critique to explore how theory can enable a “consistent conceptual comprehension both of the tendencies towards an increasingly global interconnectedness of the social world and of context specific-structural elaborations” (Schriewer, 2015, p. 7).

It is from this starting point that the author presents the following research question: How can an institutional logics approach and framework be adopted to contribute to our theoretical and empirical understanding of the global/local nexus?

Research that adopts an institutional logics approach within education is expanding, with work to date that focuses on higher education, medical education, competing logics within the discipline of inclusive education and shifting logics in kindergartens (Bastedo, 2009; Dunn & Jones, 2010; Kiuppis, 2018; Russell, 2011; Thornton & Ocasio, 1999). Building on this research and highlighting the diversity found within institutional theory and in particular neo-institutionalism, the author argues that institutional logics have much to offer in terms of explanatory power. The article draws on examples from a larger research project on student adherence to and experiences of human rights education (HRE) in International Baccalaureate (IB) schools. These examples are used to illustrate how institutional logics can contribute both theoretically and empirically to our understanding of the global/local nexus.

WCT and critics – In the context of institutional theory

Institutional theory has a long heritage that draws on multiple disciplines including Economics, Political Science, Sociology, and Organisational Studies dating back to the turn of the twentieth century (Scott, 2008). Early institutionalists ushered in the first crude form of positivism in political science, as seen during the ‘rational revolution’ in the 1970s/80s where there was an emphasis within institutional theory on rigorous and deductive methodology and a bias against normative and prescriptive approaches and methodological individualism (Scott, 2008, p. 9). However, institutional theorists also led the way in developing constructivism, such as Herbert Blumer (1931) who saw institutions as providing a framework for human conduct that must be interpreted through shared meanings and symbolic interaction (Scott, 2008, p. 12). The exploration of social reality as a human construction with the process of institutionalisation focusing on the creation of shared knowledge and belief systems rather than the production of roles and norms is also seen in the work of Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann (Berger & Luckmann, 1967).

Central to any institutional theory is the question: how do institutions affect the behaviour of individuals? In response, the ‘calculus approach’ makes the assumption that individuals behave strategically to confer maximum benefit (Hall, Taylor, & Taylor, 1996, p. 939). In contrast, the ‘cultural approach’ stresses the degree to which behaviour is bound by an individual’s worldview (Hall et al., 1996, p. 939). According to the ‘cultural approach’ institutions exist because they are so “taken-for-granted that they escape direct scrutiny and, as collective constructions, cannot be readily transformed by the actions of any one individual” (Hall et al., 1996, p. 940).

Neo-institutionalism, whilst not constituting a unified body or distinct school of thought, fits broadly into the ‘cultural’ approach. However, certain strands have evolved, for example historical institutionalism, rational choice institutionalism, discourse institutionalism, and sociological institutionalism (Hall et al., 1996; Schmidt, 2008; Suárez & Bromley, 2016; Wiseman & Chase-Mayoral, 2013). Emerging from the conceptual breadth of the neo-institutional extended family, are those who extend Zucker’s (1977) emphasis on the micro-foundations of institutional processes. In so doing, they pay closer attention to the relationship between individuals and institutions.[3] Whilst some explore institutional sources of heterogeneity in the form of institutional logics, others explore how institutionalised practices flow around the globe emphasising reception and adoption at the local level.[4] At the macro-level of research Meyer and Rowan’s (1977) insights have been extended to what has now become known as WCT. [5]

This brief background has sought to highlight that within the very rich field of institutional theory its scholars have worked to move the theory forward and in so doing utilised different ontological and epistemological stances and appropriate methodological tools. The author seeks to explore how neo-institutional theory can contribute to our theoretical and empirical understanding of the global/local nexus.

A WCT understanding of neo-institutionalism focuses on “large cultural scripts and procedural causes, which are hypothesised to exercise influence at either the supra-national, state, sub-national, organisational levels” (Wiseman, Astiz, & Baker, 2014, p. 692). Meyer and Rowan (1977) claim that actors, such as states, organisations, or legitimised individuals are embedded in institutional environments and “scripted” by world cultural assumptions and that their “structures become isomorphic with the myths of the institutional environment” (Meyer & Rowan, 1977, p. 340). Meyer and Rowan (1977) explored complex organisations as a reflection of wider myths in the institutional environment as opposed to the more technical demands of production. The process of diffusion of these myths, it has been argued, are brought about through mimetic, normative and coercive channels (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Legitimacy at the organisational level refers to the rules, requirement, rituals and expectations that organisations must adhere to, however, at the individual level actors are recognised as ‘legitimate’ when they conform to these ‘scripts’ or ‘myths’ (Schriewer, 2015). Whilst organisations may be characterised by coherence and control, structures are “decoupled” from each other and from ongoing activities, which can be seen in rule violations, unimplemented decisions, poor technical efficiency, and “subverted” or “vague” control systems (Meyer & Rowan, 1977). However, diversity and variation are also important components of WCT, as is understanding the unique and surprising ways that contemporary norms and expectations are shared across otherwise diverse and original communities (Wiseman et al., 2014, p. 694). Ramirez reminds readers that the initial formulations of WCT did not assume that “schooling is experienced in the same way across different students or schools” (Ramirez, 2012, p. 433). The concept of ‘isomorphism’ is to be seen as a process of “becoming similar in spite of conditions that would otherwise suggest diversity” (Wiseman et al., 2014, p. 698). WCT supports the notion that the local does matter and that the extent to which the global influences the local will depend upon time and space (Ramirez, 2012).

Critics of WCT argue that divergence, resistance, mimicry and coercion are underemphasised by WCT and that in a discussion of globalisation and its impact, the importance of power in its different guises and the role of actors in response to coercion must not be overlooked (Anderson-Levitt, 2012; Schriewer, 2012; Schwinn, 2012). Others have argued that it may be possible to observe a “veneer of cultural homogenisation” in supra-national organisations and policy-making at a national level (Green, 1997). However, at the same time education systems as core institutions in society are expressions of national culture that differ between and within countries having evolved from different historical, religious and cultural traditions (Green, 1997, p. 163; Hirst, Thompson, & Bromley, 2015). However, privileging the local over the global does not necessarily afford us any advantages in our understanding of the global/local nexus (Ramirez, 2012).

Emerging from discussions surrounding the nature of convergence are numerous concepts to help further our understanding of this complex phenomenon. Dale (1999) for example explores the mechanisms through which globalisation affects national policies. Steiner-Khamsi (2014) uses the concepts of ‘reception’ and ‘translation’ as an explanation for how the WCT concept of ‘decoupling’ occurs. She explores the ideological, the regulatory and the practical in her study (Steiner-Khamsi, 2014). Resnik (2012) explores ‘metamorphosis’ as the global interacts with the local using the concept of ‘frontier zone’ with six spatiality forms (Resnik, 2012, p. 251). These spatialities are according to the degree of global embeddedness and the “thickness” of the global (Resnik, 2012, p. 251). Madsen (2008) develops the concept of ‘eduscape’ to explore the dimension of the structural, with a focus on ideologies and policies and an experiential agency-based dimension. An ‘eduscape’ constitutes the ideological visions and political structures that exist in local schools including how time, activity and place are organised (Madsen, 2008). Marginson and Rhoades (2002, p. 288) using the concept of the ‘glonacal’ explore the intersections, interactions, and mutual determinations at different levels and across domains emphasising that there is not a linear flow from the global to the local.

Whilst some critics wish to discredit and abandon WCT and neo-institutional approaches completely (Carney et al., 2012; Silova & Brehm, 2015), this is not the approach taken here. Neo-institutional theory still has much to offer by way of explanatory power in helping us to better understand the global/local nexus by exploring the complexity of the institutional environment at different levels of abstraction. The author, therefore, builds on the work of WCT agreeing that to an extent there is an international HRE phenomenon even though this may not necessarily indicate that HRE can be found universally. The premise behind this is that what appears at the global level of abstraction (macro) is not necessarily experienced and adhered to at the local level (meso and micro). However, to investigate this a theoretical framework is needed that can accommodate the scale and the role of agency, to explore phenomena, such as HRE, at different levels of abstraction in different contexts. Therefore by incorporating the neo-institutional concept of institutional logics, it is proposed that a bridge can be built between the proponents of WCT and their opponents (Thornton & Ocasio, 2013, p. 101).

The Institutional logics approach

Alford and Friedland (1985) within the field of organisational studies, first introduced and defined the concept of institutional ‘logic’ (Alford & Friedland, 1985, p. 11). Developed from this was a focus on the inter-institutional system and the contradictions within it, e.g. between market and family logics (Friedland & Alford, 1991). Jackall (1988) focussed on the normative dimensions of institutions and the intra-institutional moral contradictions within organisations. Building on these, Thornton and Ocasio (1999) developed their own definition for institutional logics that they further refined in 2008 to be the “...socially constructed, historical patterns of cultural symbols and material practices, including assumptions, values, beliefs by which individuals and organisations provide meaning to their daily activity, organise time and space, and reproduce their lives and experiences” (Thornton & Ocasio, 2008; Thornton et al., 2012, p. 2). This more recent definition of institutional logics will be adopted for the purposes of this article. Institutional logics allow phenomena such as human rights to be explored as more than just ‘myths’, but as “multi-faceted, durable social structures, made up of symbolic elements, social activities, and material resources” (Scott, 2008, p. 57). It is therefore suggested here that human rights are an example of an institutional logic.

“A core premise of the institutional logics perspective is that the interests, identities, values and assumptions of individuals and organisations are embedded within prevailing institutional logics” such as the human rights logic (Thornton et al., 2012, p. 6). By drawing on the work of Pache and Santos (2013), the focus of the following framework is on the way in which individuals within an organisation experience and respond to possible competing/conflicting logics. Pache and Santos (2013) start with the premise that within a given organisation individual responses to a given logic are dependent on the extent to which they adhere to that logic. The levels of adherence described by Pache and Santos (2013) can be seen as steps on a continuum, for example, “novice, familiar or identified” (Pache & Santos, 2013, p. 3). Based on the level of adherence, individuals may respond in one of the following ways; “ignorance, compliance, resistance, combination or compartmentalization” (Pache & Santos, 2013, p. 3). The institutional logics perspective as a metatheory of institutions does not simply explain homogeneity, but also heterogeneity (Thornton et al., 2012). In so doing it moves our understanding of why heterogeneity exists at the local level beyond the WCT notion of ‘decoupling’. This is achieved by exploring logic hybridity and how it influences the ways in which logics become embedded (Pache & Santos, 2013). The institutional logics perspective sees the world as characterised by increasing institutional pluralism as organisations become embedded in sometimes competing and conflicting logics (Kraatz & Block, 2008; Pache & Santos, 2013). Logic hybridity within an organisation can arise when there are one or more institutional logics that compete for dominance. Pache and Santos (2013) argue that the relationship between adherence to a particular logic and the way in which an individual responds to that logic is moderated by the degree to which an organisation experiences logic hybridity.

Pache and Santos (2013) also note that whilst at the organisational level adherence to a particular logic or multiple logics may be needed to satisfy institutional referents, the level of response by an individual may be influenced by concerns related to social acceptance, status and identity that are external to the organisation (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Pache & Santos, 2013, p. 12). The institutional logics perspective highlights the importance of the social identities of actors in the ways in which they influence interaction with others and how these social identities interplay with logics in a given organisation (Thornton et al., 2012). The institutional logics perspective moves beyond the notion that cognitive scripts and myths explain the adoption of particular behaviours in a seemingly mindless way (DiMaggio & Powell, 1991; Friedland & Alford, 1991). From an institutional logics perspective “behaviour can also be powerful and strategic; it is mobilized when individuals and organisations violate cultural meanings” (Thornton et al., 2012, p. 42). The focus is on an integration of the different levels of analysis, but at the same time on how institutions both constrain and enable individual agency and organisations (Thornton et al., 2012). The framework adopts the concepts of adherence, experience and logic hybridity as analytical tools to better understand how the human rights logic filters down from the global to the local.

Institutional logics Framework - HRE

Alongside a plethora of international guidelines and definitions is an array of different pedagogical and theoretical approaches to HRE (Parish, 2015, p. 25).[6] What appears to be lacking from many of the studies on HRE is an explicitly stated theoretical foundation either from HRE as a discipline or from broader fields. When studies on HRE do have a theoretical foundation, it predominantly comes from WCT. HRE is one example of what is conceptualised by WCT as a myth that is spreading globally (Hafner‐Burton & Tsutsui, 2005; Kamens, Meyer, & Benavot, 1996; McEneaney & Meyer, 2000; Meyer, Bromley, & Ramirez, 2010; Meyer, Kamens, & Benavot, 1992; Meyer & Ramirez, 2000; Ramirez, Suárez, & Meyer, 2007; Suárez, 2007). Ramirez (2012) makes it clear that WCT does not make essentialist claims of “real progress” or “true justice” having been achieved towards the goals of HRE. Instead, he points out that there will always be discrepancies between, for example, policy documents and what teachers actually do in the classroom (Ramirez, 2012, p. 430). He suggests that human rights are a universal narrative that nations are expected to care about even though the reality is often different (Ramirez, 2012, p. 431).

In this article, the author draws on examples from a larger research project on student adherence to and experiences of HRE in IB schools to illustrate how a framework based on the institutional logics approach can contribute to a more syncretic understanding of the global/local. Human rights, understood as an institutional logic in the IB, is explored as an interplay between the global institutions in contradiction and interdependency (macro level), organisations in conflict and coordination (meso level), and individuals competing and negotiating (micro level) (Thornton et al., 2012). The framework enables consideration to be given to both the material and symbolic elements that are at play within organisations. The symbolic refers to the ideation and meaning – in this case, the human rights ideals. The material refers to the structures and practices within organisations – in this case, the programmes of study and the practices within school learning communities (SLC). Dynamics between the symbolic and material are explored, contributing to our understanding of how the global human rights logic (the symbolic) is embedded in the practices of the SLCs (the material) and therefore impacts the experiences and levels of adherence that students have.

This theoretical position takes its starting point from a constructivist stance whereby reality is constructed and co-constructed by actors (Leech, Dellinger, Brannagan, & Tanaka, 2010, p. 17). However, at the same time, the framework allows for the mapping of patterns that exist in the real world between students in different IB school contexts (Moses & Knutsen, 2012, p. 117). The framework draws on the post-positivist position that asserts that one can know something about an individual student’s level of adherence to the human rights logic by measuring it objectively and by using deductive reasoning (Leech et al., 2010). However, to understand why adherence develops or not, one must draw on constructivism to explore the ways in which knowledge and experience are constructed within school organisations.

Global human rights logic (macro level)

The framework begins at the macro level of abstraction with the global human rights logic. Whilst institutional logics as global phenomena have not been discussed in the literature, it is argued here that some institutional logics transcend the societal level. Taking Thornton and Ocasio’s (2008) definition of institutional logics the author argues that human rights, as a socially constructed phenomenon, has become a global logic during the course of the past century. As referred to earlier in the article, the global human rights logic is evident in the material practices set out by international law and the assumptions, values, beliefs, and rules laid out in international conventions. This logic of human rights is a part of the cultural ‘myth’ discussed in WCT literature (Boli & Thomas, 1999; Ramirez et al., 2007). The global human rights logic is evident in the material practices set out by international law and the assumptions, values, beliefs, and rules laid out in international conventions.[7] In line with Powell and Bromley (2013, p. 2) the author agrees that human rights have emerged from and are embedded in temporal processes and are historically contingent upon critical historical junctures. In the global human rights logic, we can see a macro level of abstraction.

Logic of human rights in organisational policy (macro level)

Fundamental to this framework is the way in which the global logic of human rights has become incorporated by the IB into its mission aims. The development of the IB runs parallel to the emerging logic of human rights in the second half of the twentieth century (Parish, 2018; Tarc, 2009). However, the incorporation of the human rights logic and how it is both symbolically and materially embedded in the IB historically sheds light on the degree to which there is homogeneity even at the global (macro) level (Ramirez et al., 2007). By drawing on the work of scholars within the field of international schooling it can be argued that the global human rights logic is historically embedded in the IB at a global level albeit in tension with a more pragmatic logic (Parish, 2018; Tarc, 2009). A review of the literature and policy documents of the IB reveal that at the macro level of investigation the human rights logic has become embedded within the IB as a global organisation. This embeddedness is found both in the historical construction of the IB and in current IB documents (Parish, 2018, p. 52). However, at the same time tensions exist within the IB as a global organisation between the human rights logic and more pragmatic concerns (Parish, 2018).

In this case, an understanding of if and how the global human rights logic has become and is embedded in the IB at the global level provides a benchmark with which to explore the local contexts of individual IB SLCs. At the same time, it opens our eyes to the institutional complexity within an organisation like the IB and the realisation that this can involve contestation. This, in turn, sheds light on potential logic hybridity that may exist within organisations at the global level (Pache & Santos, 2013).

Student adherence to the human rights logic (micro level)

The understanding gained in exploring the human rights logic at the macro level of abstraction is then utilised as the framework focuses on the micro level of abstraction. In the larger research project that this article takes illustrations from, adherence to the logic of human rights embedded within the IB is measured using the scores from the Human Rights Attitudes and Behavioural (HRAB) survey (Parish, 2019b). The survey, including three scales[8] and biographical data, was completed by self-selecting 16-19-year-old students in two schools. School 1 (n = 24) is a fully funded state school that caters to the academically elite students in one of the larger cities in Poland. School 2 (n = 35) is a private international school located in Norway. Findings showed that there were significant differences between the students’ HRAB scores in school 1 compared to school 2 and adherence to the human rights logic of the IB is not uniform between schools. (Parish, 2019a). At the global organisational level, the IB appears to have a mission aim and IB Learner Profile that provides cohesion across the IB continuum of programmes (International Baccalaureate Organisation, 2008). Yet significant differences are found between students in two schools when measuring for very explicitly stated aspects of the IB’s human rights logic – identification with all humanity, ethno-cultural empathy and positive human rights attitudes and behaviours (The HRAB survey) (Parish, 2019b). By exploring the embeddedness of the human rights logic from the global to the local a disconnect is revealed and possible reasons for this disconnect are explored in the final part of the framework.

Local school logic of human rights (meso level)

Within the IB as a global organisation, we find an increasing number of IB authorised schools. These school organisations represent the meso level of abstraction and the final part of this framework focuses on the reception and adoption of the human rights logic at the local level by exploring how the human rights logic is experienced by students.

Using the scores from the HRAB survey a small group of students with differing levels of adherence and the school IB coordinator participated in semi-structured interviews. The aim of the interviews was to explore how those students experience the IB human rights logic in the SLC and beyond, in an attempt to understand why they have or have not developed high levels of adherence. The interviews looked at how the SLCs have understood and responded to the global human rights logic adopted by the IB from the perspective of the IB coordinator. In addition, the interviews looked at how the students experience the human rights logic of the IB in the SLC. Whilst an assessment of the student levels of adherence provides patterns of similarity/difference between and within school contexts, the exploration of experiences at the meso level provides us with a better understanding of why these patterns of similarity/difference may exist.

Findings indicated that within SLCs the responses of the individual students to the IB human rights logic varies depending on the academic subjects that they take within the IB programme and the degree to which they commit to the Creativity Action Service programme of the programme (IBO, 2008). Other factors include the experiences that they have beyond the SLC for example, family, media, travel experience and community (Parish, 2018). In a comparison between the two schools, differences in student levels of adherence were attributed to the level of diversity within the SLC. Secondly, differences were related to the prioritisation of the human rights logic in the private school in Norway as opposed to the prioritisation of more pragmatic concerns in the state school in Poland. Finally, it emerged that factors external to the SLC must be taken into account when we are looking at the development of human rights competence in students and therefore the level to which they adhere to the human rights logic.[9]

Conclusion

Taking as its starting point the theoretical debate within CIE surrounding the global/local nexus, this paper posed the question: How can an institutional logics approach and framework be adopted to contribute to our theoretical and empirical understanding of the global/local nexus?

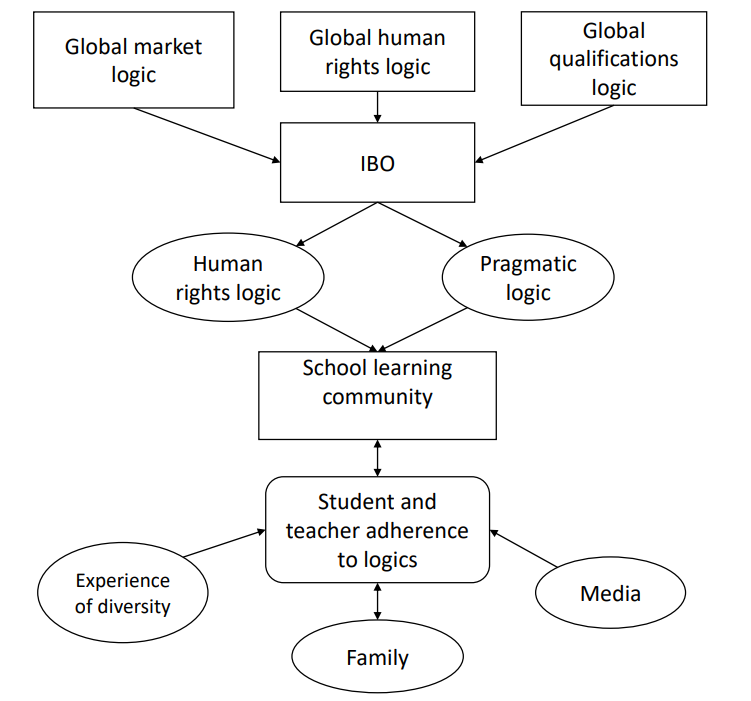

With a brief introduction to institutional

theory, the article focused specifically on neo-institutionalism, from which

has emerged both WCT and institutional logics. After presenting institutional

logics the article outlined a framework for researching HRE based on this

approach. The institutional logics approach and framework have been illustrated

with examples from the larger research project on HRE in the IB. A framework

based on institutional logics has contributed to a more syncretic and holistic

understanding of the complexity of the institutional environment within the

context of the IB, as illustrated in Figure 1. The IB with its human rights

logic represents the adoption of aspects of world culture discussed in the

literature (Meyer & Rowan, 1977). This logic in conjunction with a more

pragmatic logic impacts the SLC to different degrees depending on the local

context, type of school and its priorities. At the same time, the individual

students and teachers within the SLC bring to the school their own experiences

from family, the media, and their own experiences of diversity. Therefore the

SLC becomes a melting pot of different material and symbolic aspects (Thornton

et al., 2012). The SLC adheres to the structural and ideological restraints of

the IB organisation, reflecting the role of coercion, but at the same time, it

is influenced by and influences the students and teachers, reflecting the role

of agency.

Figure 1. A diagrammatic representation

of complexity in the institutional environment.

To conclude, the author proposes that by adopting an institutional logics approach and framework we can gain a better theoretical and empirical understanding of the global/local nexus and at the same time provide a much-needed bridge between the opposing views in this ongoing debate within the field of CIE. Whilst the example of HRE has been offered by way of illustration in this paper, it seems logical to propose that this theoretical approach and framework could also be applied to other phenomena of interest to the CIE community such as inclusive education, school choice, performance, accountability and marketisation. These can be seen as “...socially constructed, historical patterns of cultural symbols and material practices, including assumptions, values, beliefs by which individuals and organisations provide meaning to their daily activity, organise time and space, and reproduce their lives and experiences” (Thornton & Ocasio, 2008; Thornton et al., 2012, p. 2). Agency, coercion and power play an important role in the ways in which and the extent to which these different logics co-exist or compete at the different levels of abstraction, revealing complexity within the institutional environment.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank an anonymous reviewer, Florian Kiuppis, Heidi Biseth, Tristan Bunnell and Jenny Steinnes for valuable feedback received on an earlier draft.

References

Alford, R. R., & Friedland, R. (1985). Powers of theory: Capitalism, the state, and democracy. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Almandoz, J. (2012). Arriving at the starting line: The impact of community and financial logics on new banking ventures. Academy of management Journal, 55(6), 1381-1406. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0361

Anderson-Levitt, K. M. (2003). A world culture of schooling? In K. M. Anderson-Levitt (Ed.), Local meanings, global schooling: Anthropology and world culture theory (pp. 1-26). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Anderson-Levitt, K. M. (2012). Complicating the concept of culture. Comparative Education, 48(4), 441-454. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2011.634285

Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at large: Cultural dimensions of globalization (Vol. 1). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minneapolis Press.

Archard, D. (1996). Philosophy and pluralism (Vol. 40). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Bajaj, M. (2011). Human rights education: Ideology, location, and approaches. Human Rights Quarterly, 33(2), 481-508. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/23016023

Bastedo, M. N. (2009). Convergent institutional logics in public higher education: State policymaking and governing board activism. The Review of Higher Education, 32(2), 209-234. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.0.0045

Battilana, J., & Dorado, S. (2010). Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of management Journal, 53(6), 1419-1440. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/29780265

Berger, P., & Luckmann, T. (1967). The social construction of reality. London: Allen Lane. London, England: Random House.

Blumer, H. (1931). Science without concepts. American Journal of Sociology, 36(4), 515-533. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/2767159

Boli, J., & Thomas, G. M. (1999). Constructing world culture: International nongovernmental organizations since 1875. California, CA: Stanford University Press.

Brunsson, N., & Jacobsson, B. (2000). A world of standards. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Carney, S. (2009). Negotiating policy in an age of globalization: Exploring educational “policyscapes” in Denmark, Nepal, and China. Comparative Education Review, 53(1), 63-88. https://doi.org/10.1086/593152

Carney, S., Rappleye, J., & Silova, I. (2012). Between faith and science: World culture theory and comparative education. Comparative Education Review, 56(3), 366-393. https://doi.org/10.1086/665708

Czarniawska, B., & Sevón, G. (1996). Translating organizational change (Vol. 56). Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter.

Dale, R. (1999). Specifying globalization effects on national policy: a focus on the mechanisms. Journal of Education Policy, 14(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/026809399286468

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147-160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

Dunn, M. B., & Jones, C. (2010). Institutional logics and institutional pluralism: The contestation of care and science logics in medical education, 1967–2005. Administrative science quarterly, 55(1), 114-149. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2010.55.1.114

Friedland, R., & Alford, R. R. (1991). Bringing society back in: Symbols, practices and institutional contradictions. In W. W. Powell & P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis (pp. 232-263). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago.

Green, A. (1997). Education, Globalization and the Nation State. Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY.

Hafner‐Burton, & Tsutsui. (2005). Human Rights in a Globalizing World: The Paradox of Empty Promises. American Journal of Sociology, 110(5), 1373-1411. https://doi.org/10.1086/428442

Hall, P. A., Taylor, R. C. R., & Taylor, R. C. R. (1996). Political science and the three new institutionalisms. Political Studies, 44(5), 936-957. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/43185

Hirst, P., Thompson, G., & Bromley, S. (2015). Globalization in question. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

International Baccalaureate Organisation. (2008). Creativity, action, service guide. Retrieved from https://www.scotch.wa.edu.au/upload/pages/ib-diploma-curriculum/cas-guide.pdf

International Baccalaureate Organisation. (2008). IB learner profile booklet. Retrieved from http://wcpsmd.com/sites/default/files/documents/IB_learner_profile_booklet.pdf

Jackall, R. (1988). The Moral Maze. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Kamens, D. H., Meyer, J. W., & Benavot, A. (1996). Worldwide patterns in academic secondary education curricula. Comparative Education Review, 116-138. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/1189047

Kasuya, K. (2001). Discourses of linguistic dominance: a historical consideration of French language ideology.InternationalReviewofEducation,47(3-4)235-251. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1017993507936

Kiuppis, F. (2018). Inclusion in sport: disability and participation. Sport in Society, 21(1), 4-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2016.1225882

Kraatz, M. S., & Block, E. S. (2008). Organizational implications of institutional pluralism. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin-Andersson, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (Vol. 840, pp. 243-275). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Leech, N. L., Dellinger, A. B., Brannagan, K. B., & Tanaka, H. (2010). Evaluating mixed research studies: A mixed methods approach. Journal of mixed methods research, 4(1), 17-31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689809345262

Madsen, U. A. (2006). Imagining selves. School narratives from girls in Eritrea, Denmark and Nepal Ethnographic comparisons of globalization and schooling. Young, 14(3), 219-233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308806065817

Marginson, S., & Rhoades, G. (2002). Beyond national states, markets, and systems of higher education: A glonacal agency heuristic. Higher education, 43(3), 281-309. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014699605875

McEneaney, L. H., & Meyer, J. W. (2000). The content of the curriculum. In M. T. Hallinan (Ed.), Handbook of the Sociology of Education (pp. 189-211). New York, NY: Springer.

McFarland, S. (2010). Personality and support for universal human rights: A review and test of a structural model. Journal of personality, 78(6), 1735-1764. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00668.x

McFarland, S., Brown, D., & Webb, M. (2013). Identification with all humanity as a moral concept and psychological construct. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(3), 194-198. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721412471346

McFarland, S., & Mathews, M. (2005). Who cares about human rights? Political Psychology, 26(3), 365-385. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00422.x

McFarland, S., Webb, M., & Brown, D. (2012). All humanity is my ingroup: A measure and studies of identification with all humanity. Journal of personality and social psychology, 103(5), 830. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028724

Meyer, J. W., Bromley, P., & Ramirez, F. O. (2010). Human Rights in Social Science Textbooks: Cross-National Analyses, 1970-2008. Sociology of Education, 83(2), 111-134. https://doi.org/10.1177/00380407103679366

Meyer, J. W., & Ramirez, F. O. (2000). The world institutionalization of education. In J. Schriewer (Ed.), Discourse formation in comparative education (pp. 111-132). Frankfurt, Germany: Peter Lang.

Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2),340-363. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/27782933

Moses, J., & Knutsen, T. (2012). Ways of knowing: Competing methodologies in social and political research. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Pache, A.-C., & Santos, F. (2013). Embedded in hybrid contexts: How individuals in organizations respond to competing institutional logics. Research in the Sociology of Organizations, 39, 3-35. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0733-558X(2013)0039AB014

Parish, K. (2015). Studying Global Human Rights Education. Theoretical and Empirical Approaches. Opuscula Sociologica, 13(1), 23-35. https://doi.org/10.18276/os.2015.1-02

Parish, K. (2018). Logic hybridity within the International Baccalaureate: the case of a state school in Poland. Journal of Research in International Education, 17(1), 49-66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240918768986

Parish, K. (2019a). An embedded human rights logic? A comparative study of International Baccalaureate schools in Norway and Poland. Unpublished paper.

Parish, K. (2019b). A measure of human rights competence in students enrolled on the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme. Oxford Review of Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2018.15518011

Phillips, D., & Schweisfurth, M. (2014). Comparative and international education: An introduction to theory, method, and practice: A&C Black.

Powell, W. W., & Bromley, P. (2013). New Institutionalism in the Analysis of Complex Organizations. In J. Wright (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of Social and Behavioral Sciences (Vol. 2, pp. 764-769). Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier.

Ramirez, F. O. (2012). The world society perspective: Concepts, assumptions, and strategies. Comparative Education, 48(4), 423-439. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2012.693374

Ramirez, F. O., Suárez, D., & Meyer, J. W. (2007). The worldwide rise of human rights education. In C. Braslavsky, A. Benavot, & N. Truong (Eds.), School knowledge in comparative and historical perspective (pp. 35-52). New York, NY: Springer.

Russell, J. L. (2011). From Child’s Garden to Academic Press The Role of Shifting Institutional Logics in Redefining Kindergarten Education. American Educational Research Journal, 48(2), 236-267. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/27975289

Schmidt, V. A. (2008). Discursive institutionalism: The explanatory power of ideas and discourse. Annual review of political science, 11. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060606.135342

Schriewer, J. (2012). Re-conceptualising the Global/Local Nexus: Meaning Constellations in the World Society. Special issue, Comparative Education, 48(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2012.737233

Schriewer, J. (2015). World culture re-contextualised : meaning constellations and path-dependencies in comparative and international education research. Oxford, England: Routledge.

Schwinn, T. (2012). Globalisation and regional variety: problems of theorisation. Comparative Education, 48(4), 525-543. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2012.728048

Scott, W. R. (2008). Institutions and organizations: ideas and interests (3rd ed. ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Silova, I., & Brehm, W. C. (2015). From myths to models: the (re) production of world culture in comparative education. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 13(1), 8-33. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2014.967483

Steiner-Khamsi, G. (2004). The global politics of educational borrowing and lending. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Suárez, D., & Bromley, P. (2016). Institutional theories and levels of analysis: History, diffusion, and translation. In J. Schriewer (Ed.), World culture re-contextualised : meaning constellations and path-dependencies in comparative and international education research (pp. 139-159). Oxford, England: Routledge.

Tarc, P. (2009). Global dreams, enduring tensions: International Baccalaureate in a changing world. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Thornton, P. H. (2004). Markets from culture: Institutional logics and organizational decisions in higher education publishing. California, CA: Stanford University Press.

Thornton, P. H., & Ocasio, W. (1999). Institutional logics and the historical contingency of power in organizations: Executive succession in the higher education publishing industry, 1958–1990 1. American Journal of Sociology, 105(3), 801-843. https://doi.org/10.1086/210361

Thornton, P. H., & Ocasio, W. (2008). Institutional logics. In C. Oliver & R. Greenwood (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (Vol. 840, pp. 99-128). New York, NY: Sage.

Thornton, P. H., & Ocasio, W. (2013). Institutional logics. In L. L. Putnam & D. K. Mumby (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational communication: Advances in theory, research, and methods (pp. 99-129): Sage Publications.

Thornton, P. H., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012). The institutional logics perspective: A new approach to culture, structure, and process. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press

Tibbitts, F. (2002). Understanding what we do: Emerging models for human rights education. International Review of Education, 48(3-4), 159-171. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3445358

Tibbitts, F., & Kirschlaeger, P. (2010). Perspectives of research on human rights education. Journal of Human Rights Education, 2(1), 8-29. Retrived at http://blogs.cuit.columbia.edu/peace/files/2013/05/tibbitts_kirchschlaeger_research_hre_jhre_1_2010.pdf

Wang, Y. W., Davidson, M. M., Yakushko, O. F., Savoy, H. B., Tan, J. A., & Bleier, J. K. (2003). The scale of ethnocultural empathy: development, validation, and reliability. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(2), 221. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.50.2.221

Wiseman, A. W. (2010). The uses of evidence for educational policymaking: Global contexts and international trends. Review of Research in Education, 34(1), 1-24. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/40588172

Wiseman, A. W., Astiz, M. F., & Baker, D. P. (2014). Comparative education research framed by neo-institutional theory: A review of diverse approaches and conflicting assumptions. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 44(5), 688-709. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2013.800783

Wiseman, A. W., & Chase-Mayoral, A. (2013). Shifting the discourse on neo-institutional theory in comparative and international education. In A. W. Wiseman & E. Anderson (Eds.), Annual Review of Comparative and International Education (pp. 99-126). Bradford, England: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Zilber, T. B. (2002). Institutionalization as an interplay between actions, meanings, and actors: The case of a rape crisis center in Israel. Academy of management Journal, 45(1), 234-254. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069294

Zucker, L. G. (1977). The role of institutionalization in cultural persistence. American Sociological Review, 726-743. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094862