NJCIE 2019, Vol. 3(3), 61–74

http://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.3274

Spatial Manoeuvring in Education: Educational Experiences and Local Opportunity Structures among Rural Youth in Norway

Unn-Doris K. Bæck[1]

Professor, Department of Social Sciences, UiT The Arctic University of Norway

Abstract

Based on an interview study of upper secondary school pupils in a county in Northern Norway and against a backdrop of spatial differences in dropout rates in upper secondary education in Norway, this article explores the significance of space for understanding the experiences of young people in the transition from lower to upper secondary education. The situation of rural youth is particularly highlighted. Through interviews with students, four factors connected to spatiality and more specifically to spatial mobility have been pinpointed. These are connected to (1) local school structures, (2) local labour markets, (3) being new in a place, and (4) localised social capital. At a more theoretical level, the concept of opportunity structure is employed in order to grasp how structures connected to education, labour market, and economy can have a profound effect on the lives of young people, being subjected to a mobility imperative that has become a particularly relevant driving force for rural youth.

Keywords: opportunity structure; rural education; mobility; place; rural; youth

Introduction

Where you live matters when it comes to educational performance and careers, and worldwide there is considerable empirical evidence documenting significant differences between students residing in more rural versus more urban settings (Green & Corbett, 2013). Despite this, problematising the significance of space in education is often missing in education research, where urban space seems to be presupposed as the norm (Bæck, 2015; Butler & Hamnett, 2007; Hargreaves, Kvalsund & Galton, 2009). In this article the aim is to put forward the significance of space when it comes to the way young people in Norway relate to educational plans and show how space forms their educational aspirations and experiences. Certain elements significant for educational experiences will be highlighted that makes space a relevant factor when it comes to, for example, understanding early school leaving.

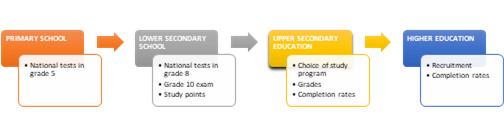

In Norway, differences between rural and urban settings can be documented on a number of measures of educational success throughout the education system, as illustrated in figure one. In primary school (grades one—seven) this is shown in national tests in mathematics, reading, and English, carried out by all grade five students in Norway. In lower secondary school (grades eight—ten), spatial differences are visible in national tests in mathematics, reading, and English, carried out by all grade eight students in Norway. The same is true for the results of the final exams in grade 10. The grade levels and final exams in lower secondary school are the foundation for admission to upper secondary education. In upper secondary education there are geographical differences when it comes to choice of study programme and the probability of completing. Also, spatial differences can be seen in students’ grades. When it comes to higher education, young people from more urban spaces are prone to get access to the more prestigious programmes in higher education because of their higher attainment levels. In higher education, there are also spatial patterns when it comes to choice of programmes and completion rates.

Figure 1: Spatial education differences throughout the education system

Thus, spatial differences in education can be found in the choices students make in the course of their educational trajectories and in their educational performance. Certainly, choices, and performances are often interrelated and hard to distinguish, and students’ performances at one level of the education system can close off a range of choices available at the next level. However, it is also the case that students with the same level of performance, but residing in different geographic settings, make different choices within the education system. This is demonstrated by, for example, Falch and Nyhus (2009) in a study where the northern part of Norway, the most rural part of the country, is compared to other regions. Their study shows that while high dropout rates in vocational education and training (VET) in upper secondary education are in general associated with low achievement levels from compulsory education, the situation in the north of Norway is an exception, where high dropout rates in VET are independent of admission points. Thus, students with the same level of performance conduct different choices when it comes to leaving school; sometimes these decisions have a spatial twist to them.

Upper Secondary Education as a Spatial Structure

In this article, the main focus is on upper secondary education, a part of the education system where spatial differences are most visible. In Norway, there is 10 years of compulsory schooling, before you choose upper secondary education: either a three year academic track or a three to four year vocational track. Dropout rates have received considerable attention in Norway for many years, as the dropout rates are considered to be too high. Studies show that grades from lower secondary school and family background characteristics (SES) are the most significant predictors of dropout (Byrhagen, Falch & Strøm, 2006). In addition, the northernmost, and most rural, counties of Norway have higher dropout rates compared to most other places in the country (Lie, Bjerklund, Ness, Nygaard & Rønbeck, 2009; Markussen, 2016). In the county where this study took place, Troms county (the second northernmost county in Nor-way), 52% of the students completed their education on time, compared to the national number of 59%. It is important to note that the county average for the education performance indicators mentioned, does not show that pupils in primary and lower secondary schools in Troms underperform compared to the national average. In fact, national tests in grades five and eight show that pupils in Troms are slightly above the national average in mathematics, reading, and English, indicating that the pupils should be equally capable to handle the transition between lower and upper secondary school as their counterparts other places in Norway. In this article, we will point out some spatial features that may serve to explain why this is not the case. Also important to note, is that even though the average numbers for Troms show that pupils perform at the national level, there is considerable geographic variation in scores on the national tests and other measures of educational success within the county.

When young people plan to enter upper secondary education there are certain structural elements connected to the school system itself that they have to relate to. In Norway, the counties (fylkeskommunen) are the school owners and make decisions regarding how upper secondary education is set up in each county. School structure is, to a large extent, a result of political decisions closely linked to economic priorities and is constantly under scrutiny. Especially small, rural schools are under a constant threat of closure because of financial unsustainability and decreasing student populations, as we also know from other national settings (for example Kalaoja & Pietarinen, 2009; Knickle, 2014). In the county where this study took place, the number of primary and lower secondary schools decreased by 20% over the past 20 years. In this county, the closing down of study programmes in upper secondary schools is repeatedly discussed, and schools located in rural areas are in more precarious situations than in more urban areas. During the last few years a centralisation of the upper secondary school system has been taking place, where schools have been amalgamated into joint administrative units. Centralisation has also taken place through a geographic centralisation of study programmes within the counties. This means that fewer students will have a wide selection of study programmes to choose from within the vicinity of their homes and in order to fulfil their preferred choice of study programme, more students have to move away from home or commute long distances.

Students in VET are especially vulnerable for spatial variations since this part of the education system is tied closely to local and regional labour markets. In the north of Norway, more students will choose VET compared to others parts of the county. While 30% of the students in Oslo attend VET, the same is true for 59% of the students in Finnmark (the northernmost county) and 52% of the students in Troms. VET students have two years of in-school education, followed by two years of in-company training to complete an apprenticeship diploma. This is when the spatial challenges are made especially relevant, since they have to rely on the local and regional labour markets in order to be able to complete their education. In the rural communities the companies offering to take on apprentices are small and many of them do not have a strong tradition for formal learning and formal qualifications, which can create challenges for the apprentices. There are not enough available apprenticeship positions for all those who apply, there are waiting lists that can drag out over time – and for too many of them their education ends here, without completing the apprenticeship programme.

Opportunity Structure as Analytic Intake

School internal issues, such as curriculum, learning goals, and pedagogics, are important in order to understand educational processes. When analysing spatial effects on individual education trajectories, however, including societal processes is also necessary. In order to do so, the notion of place as opportunity structure, first coined by Cloward and Ohlin (1960) in their analyses of the formation of delinquent gangs, is useful since it has to do with the context in which educational choices are conducted.

As pointed out elsewhere (Bæck, 2015), interpreting places as entities that provide individual, structural, and cultural conditions for action and choices, turns attention towards the spatial patterning of the educational system and of work opportunities. Different places constitute different opportunity structures, providing different conditions and barriers that directly and indirectly promote or hinder opportunities for individuals, which may again affect students’ motivations and choices. These conditions and barriers may have to do with, for example, local outbid of educational institutions and range of study programmes, local or regional labour opportunities, or logistic barriers such as public transport. There are, for example, other alternatives to school in areas with less knowledge demanding labour markets, than in areas where the majority of work places demand formal qualifications. For young people, such aspects constitute a structure against which they evaluate which strategies and actions are considered feasible and which are not. In this way, the perspective of opportunity structure draws attention towards the context where choices are conducted.

Behind such opportunity structures are economic deliberations and priorities, at the local, regional, and national levels, which highlights the link between economic and political decisions impacting resource allocations to the education sector. In the county where this study took place, economic priorities have time and time again resulted in school closures and amalgamations, especially for the small, rural schools which are often under the threat of closure. School closures represent practical challenges for students in more remote areas, as they inevitably lead to longer commuting distances, creating more strenuous circumstances for the students.

The spatial structure of the educational system, local variations when it comes to resources allocated to education, disparities in access to learning resources, differences in teacher recruitment and retention, are factors that are crucial for the quality of the education offered. Local presence of educational institutions is in itself part of an opportunity structure that forms young people’s perceptions of possible and probable educational routes, which may in turn impact individual school motivation and choices.

Educational decisions have a spatial character to them as they are coloured by the educational opportunities present in a given location at a given point in time. However, such educational opportunity structures also represent a foundation for how young people see their futures in a certain location. According to Corbett (2016), rural schools have historically played an ambivalent role when it comes to such “imagined futures” since successful education would mean an urban future for mobile individuals who did not have an attachment to rural home communities. Corbett has also coined this through his expression of “learning to leave”, showing how the education system serves to qualify young people for life outside of the rural communities (Corbett, 2007). Similar issues have been claimed by other researchers who have also pointed out that the encounters between the education system and rural students are experienced as challenging since the education system presupposes cultural orientations that rural students are more unfamiliar with (Hoëm, 1976, 2010; Tiller, 1990).

Education, work preferences, and plans are an important part of young people’s imagined futures, and rural youth’s education and work preferences are not only affected by local or national political decisions, as described above. Supralocal influences such as school and social media are also central and increasingly so---and young people, irrespective of location, often express similar evaluation schemes for what constitutes a “good home place”, dominated by elements characteristic of an urban lifestyle or an urban ethos (Bæck, 2004). Since the possibilities to meet such preferences are usually slimmer in rural compared to urban areas, fulfilling such preferences inevitably confront rural youth with the choice of relocating. Svensson (2006) reports similar findings from a study in a small town in Sweden, documenting that across social groups and gender young people felt that it would be easier to achieve values that they considered important in a big city than in a more rural setting.

Young people’s interpretations of their opportunities to live out their preferences may in turn influence their motivations to learn, their beliefs about their own abilities and their learning strategies. Rural youth may be placed in a sort of double bind, especially those with less resources at hand, because while they share the dreams, hopes, and preferences of their urban counterparts, it will be more difficult for them to have their dreams or expectations fulfilled, without relocating—and many of them will not have the means to do so.

The Aim of the Study and the Research Approach

The aim of this article is to explore how students in different locations orient themselves when it comes to education. The main research questions have to do with how students relate to spatial issues when they reflect on their educational plans and choices and how spatial factors influence students’ experiences in school. The focus is on factors that may influence students’ possibilities to perform well in school as well as factors that constitute the structural and material reality against which students make their choices regarding education.

The analyses are based on 54 qualitative interviews collected among upper secondary school students in seven upper secondary schools in a county in Northern Norway. The main objective for the study was to investigate early school leaving in upper secondary education in the north of Norway, which is a major problem in many rural places; in some places as few as 30% of students finish on time. The students were interviewed during their last semester of their first year in upper secondary school. The majority of the students are in vocational education, and two thirds of them are girls. Four of the schools are located in what we may call rural settings, while the other three are located in two different towns in the county. While all of the schools recruit students from both rural and urban areas, the student body of the four schools in rural locations consists primarily of rural students, with just the occasional student from one of the more urban places in the county.

Spatial Manoeuvring in Education

The majority of the upper secondary school students interviewed emphasised education and work as essential parts of their future, and the data analyses do not show any outspoken spatial variation when it comes to educational aspirations and preferences. The overall and heavy emphasis on education and the whole knowledge paradigm seem to be taken for granted. The students engaged in these issues not so much as individual actors, but as parts of collective groups. The students were part of family units where education was considered a self-evident part of life and of the future, and in the decision-making processes that these young people engaged in, they reached their decisions in cooperation with their families and with input from them. At some level, referring to these processes as decision-making may be somewhat inaccurate, since the main decision of whether or not to pursue an education after compulsory schooling, did not come across as a real decision. Rather, it was self-evident, not least in the minds of the students. There are, however, variations in terms of how much education and what kind of education that is considered realistic and sensible in different families.

The data material showed that there are variations in terms of what kind of factors the young students talk about when asked questions about making their way through the education system, and this can be connected to the spatial reality they relate to. In the following paragraphs, four different factors in the complex web of spatial differences in education, will be highlighted.

Local School Structures - a Fact of Life

As shown in the introduction, spatial differences in the upper secondary education system is a reality in Norway. Proximity to educational institutions and range of available study programmes are factors that vary according to place of residence, and how the school structure is set up has a direct impact on the everyday lives of young people. In this sense, young people residing in different geographical locations relate to different school structures. While students residing in urban areas will have all study programmes available in close vicinity, the rural students in this study had to orient themselves when it comes to which study programmes are offered where. The students talked about this as an important part of thinking about schooling after compulsory school, and in this way they are forced to engage in place-specific reflections and decision-making processes when it comes to education. At the same time, however, they talked about it in a very matter-of-fact way. Everyone knows that if you want to get an education, you have to move, and for those who had siblings who had moved away to go to school, the family had already been through the same process.

One of the girls explained how she planned her years in upper secondary education. She was in a VET programme, but she did not, however, plan to achieve vocational competence (with or without a trade or journeyman’s certificate). Instead she planned to complete her third year in a supplementary programme for general university admissions certification:

First, I’ll finish the first year of “Healthcare, childhood and youth development” and live at home. Then, next year, I will do “Childcare and youth work” - I have to move to Sjøvegan to do that. So, I have to live in a bedsitter. And then, I want to do the third year of general academic studies and get the university admissions certification. That I can do at Høgtun, so I can live at home. After that I will move to Tromsø and start university there.

When asked what she thought of having to move away next year, she did not really see this as a problem. Although, as she said:

Many of my friends who live away from home are complaining that they miss their families and that they are not eating properly and so on. Cause all of a sudden they run out of food, and then they need money, and then they have to go to the store and all that. And also, it may be lonely, living by oneself.

Even though having to move away at an early age, and in this way having to be willing to be mobile, is considered a fact of life for those who want to pursue an education, this does not mean the youth and their families did not also reflect on the potential negative aspects of moving. Several of the them could also tell stories and give examples of people they knew who had not been able to cope with living away and who had come back to the local community.

Local Labour Markets

As mentioned in the introduction, VET students are particularly vulnerable for spatial variations since they are dependent on apprenticeship positions in order to complete their education. Local labour markets are crucial because they constitute a structure that the young evaluate their opportunities according to. Labour markets represent future work possibilities for the young, which is relevant when it comes to envisioning adult life and a future in a given location. This is something that the students interviewed were preoccupied with. They reflected upon what kind of job they would be able to get if they should continue to live at home, and also upon what kind of work that would be available should they move out for education and then decide to return back home as adults.

Another aspect is that a local labour market can serve as a pull factor for students who are considering leaving school. Some of the students interviewed reside in places with less knowledge demanding labour markets where young people without formal qualifications can be able to find work. If there is work available, the decision to drop out of school becomes easier. In the data material, the boys talked about this more than the girls, which reflects the existence of gender divided local labour markets where it is easier for boys to secure unskilled work. In the interviews, the VET students in the study also pointed out that the local labour market could serve as a form of safety blanket. They were aware of the potential trouble of securing apprenticeship positions, but at the same time they did not seem too worried. Some talked about how they would be able to utilise some local contacts they had, neighbours, relatives, or friends of the family, in order to secure a position. Also, for some of them, should they fall out of school, there would still be options for them at home, they said.

Local labour markets can also serve as a factor that may make students stay in school. In areas where there is a lack of job opportunities, that is, less alternatives to school, it is “harder” to make the decision to drop out. This seems to be especially true for the girls. In the interviews, some of the students also related this to their parents’ situation. They had seen their own parents struggling in the local labour markets, and they did not want to go through the same. Also, the parents themselves would explicitly tell them not to make the same mistakes as they had made. In this sense, the parents are an important driving force in order to encourage the young to think about geographic mobility and not limit themselves in space.

Being New in a School

A result of the local school structure, as described in the introduction, is that a large number of young people living in rural areas have to travel long distances to go to school. Some of the informants in the study had one hour bus rides each way, so their school days were long and tiresome. Some of the informants lived in school dormitories, with other relatives, or in bedsitters. At 15 or 16 years of age, this situation is bound to have an effect on school motivation and education outcomes for the students. The social aspects of changing schools and moving away from home was mentioned by several in the interviews.

One of the rural students who had moved to town to go to school, talked about how she experienced starting upper secondary school without knowing anyone else in the class. She had a hard time socially, which also made it difficult for her to relate to the subjects and to be active in class:

I didn’t know anyone in the class. And no one seemed to want to get to know me. So, most of the time I would sit by myself. So, it became harder, the subjects and to follow what went on during the lessons. I didn’t raise my hand, because… Well, it was just harder, to follow the class. I am not sure why. It was harder to “meddle” in what went on during the lessons. I felt like I was on the outside. Especially with the group work. Everyone else in the class knew each other, and I was just from this island and didn’t know anyone.

This student made the connection between the challenging social situation she found herself in and experiencing the subjects as more difficult. When the social aspect is challenging, it is harder to step up during the lessons as well. In her case, the move from a safe, well known environment in a school with 50 students, to a school with several hundred students, was brutal. She did very well in lower secondary school, with excellent grades, but the social situation made the transition to upper secondary school hard for her. “My old school was really nice”, she said, “We were not that many pupils and we all knew each other very well. And we knew the teachers, since the teachers could even be your neighbour or your relative. So yes, it was a nice school--- you learnt a lot and there was always a teacher there you could talk to.” This student had great expectations as to all the new friends she would meet in the new school, but she found this was much harder than expected. In her case, though, it worked itself out over time--- she was able to change classes and she also lived in the school dormitory which made it easier for her to socialise.

Students in this study emphasised the social aspect of going to school as the main motivating factor for sticking with it. For those who are not able to secure a social environment for themselves, when this safety blanket is missing, the decision to drop out may become easier.

Loss of Social Capital

As shown above, several of the students who went to an upper secondary school away from their home place, experienced that their social situations would change as a result of the move. Their social positions would have to be renegotiated and re-established, and a lot of the students talked about this as hard work. They could also experience challenges of a more practical nature: for example, connected to getting a part-time job in the new place. For some of the students getting a job was a deed of necessity, since living away from home would cause a strain on the family economy. One of the students talked about how he was not able to get a part-time job at the new place, while he had not experienced that problem when he had lived at home:

I can’t find work. I had a job when I lived at home. I used to work in the fish-plant. My mum worked there, so I could also get a job there.

It was hard to keep the job after having moved away, even though he travelled home every weekend.

When I am home in the weekends there are so many things to do. I have to wash my clothes and everything ---and then I have to travel back by bus early on Sunday.

For young people this age, family ties play a major role when it comes to opportunities to get a job. As one informant said:

It was kind of like a family business, so if you were not family, it was impossible to get a job there.

For this young boy, finding a job in the new place was impossible. The social capital that he had was locally anchored, and it only had value within the confines of the local community that he had left. Social capital is related to social networks: knowing people that are valuable in the sense that their connections can work as a form of resources. Moving away means losing this capital, at least in their everyday life at the new place. It could still be a valid asset when they went home in the weekends, but in the new place the social capital that they used to have would be worthless. For the young people in the study, social capital in this way comes across as an important factor for those who had to relocate in order to attend upper secondary education. The presence of social capital through the social relations they were part of at their home place, and the absence of social capital through such relations after relocating to a new place, is evident in the stories told by the young.

Social capital is also taken into consideration in the strategising these young people are engaged in when planning for the future. In the interviews, they would picture several scenarios, and seemed to have some form of preparedness for the possibility that things may not necessarily play out exactly as in their plan A. Social capital could come in handy if that should occur. For example, activating social capital at the home place could be necessary in order to secure a temporary job if they should decide to drop out of school. And even if the need to activate the social capital did not occur, it still comes across as important, as a potential asset. The reassurance of having some form of safety net back home, a plan B, seemed to make facing spatial mobility and being away easier to handle for the young. In that sense, the value of social capital extends beyond the confines of the local community. Social capital as a form of localised capital, therefore, has an over-local quality to it.

The interview data shows that students employ different strategies in order to manoeuvre in an educational landscape and that these strategies are, in part, dependent on their spatial positions. For one thing, and here the roles of family, parents, and older siblings are important, these youth seem to be counting spatial mobility as a fact of life. Growing up with the knowledge that continuing education after grade 10 necessarily implies leaving the community, and seeing their siblings and others around them going through this move, makes them see themselves as mobile. It is simply the way it has to be and it goes without saying. In one sense, the implicitness of moving away very young serves as a form of preparation for the inevitable. At the same time, however, the experiences expressed by some of the students interviewed here, shows that it is hard to be fully prepared for the actual move and many of them struggle with the new circumstances. For them it is very important to maintain close contact with family, but also with the home community itself. They seek to balance being away and being home and they remain connected to home even though they are in a sense “forced” out. In a study from rural Australia, Cuervo and Wyn (2012) describe much of the same dynamic. They found that for many of the participants in their study, higher education was chosen with the plan of returning in the future when they would be able to contribute to the community by use of their educational capital. For the young people in the present study, family, friends, and social networks continued be important, and the youngsters did not really see themselves as having moved away, but considered themselves commuters--- which is also a term that they were familiar with since many of the adults in their surroundings commuted for work. Returning home every weekend could, however, place them on the side of the social relations that formed in their new school classes, and in this sense they risked not being fully integrated in either of the two places.

Discussion and Conclusions

The starting point for this study was the transition between lower and upper secondary education. Through interviews with students, four factors connected to spatiality and more specifically to spatial mobility have been pinpointed. These are connected to (1) local school structures, (2) local labour markets, (3) being new in a place, and (4) localised social capital. In reality, the processes that these youth find themselves in when it comes to their educational trajectories include several different transition experiences. First, it has to do with a transition between two different parts of the educational system, between lower and upper secondary school. The transition brings with it an introduction to a part of the educational system where different concepts, ways of working, demands, and expectations are present. Some of the students address this transition explicitly when they talk about how the school subjects became more challenging and the teachers’ demands were higher, compared to what they had experienced in lower secondary school. It is also a transition from one physical setting (school building) to another, and of being integrated into new school classes with new classmates et cetera. The study also shows, however, that for some of the students, it is the transition from living at home to living by themselves that represents the biggest challenge and the most life-changing experience. This is important to keep this in mind when assessing the situation for this group of students. Without much extra support or backup these youngsters are expected to grapple with the transition to a new educational level with new and higher demands, while at the same time dealing with the transition from home to a much more independent life, where they have to take much more responsibility for themselves. Our study shows that this can be experienced as challenging.

In this way, pursuing an education comes with a bigger cost for some students than for others, because they are faced with more serious spatial challenges. Many rural young people relate to an educational system that offers them a limited range of options in the local setting, making some educational routes harder to realise for them than is the case for youngsters located in other geographical settings. For young people interviewed in this study, some, if not most, educational routes imply leaving home at 15--16 years of age. As shown above, the youngsters talked about having to move away at an early age as a self-evident part of life and this is something that they are prepared for.

Farrugia (2016) addresses this as a mobility imperative and shows that mobilities are especially significant for rural youth due to processes that mandate mobility, including increasing urban versus rural inequalities in a global context and the valorisation of metropolitan lifestyles in popular culture. According to Farrugia, and as also shown in the present study, this mobility imperative means that rural youth must often be mobile in order to access the resources they need to navigate biographies and construct identities. For the young rural people in the present study, access to educational credentials implies having to move away from the rural communities, whether the goal is to create a life inside of or outside of the rural. These spatial educational differences create different opportunities for young people depending on where they live. The dominant education ethos of our time makes education the self-evident route for the great majority, at least to complete upper secondary education--- and cultural capital is hardly a distinguishing feature anymore when it comes to deciding whether to continue after lower secondary school or not. The analyses in this article makes it clear that even with this educational ethos, there are structural elements that create uneven educational opportunities for young people, here understood through the term opportunity structures.

A number of the young people we interviewed described an imagined future that included clear plans for a certain occupation and a certain lifestyle. For some of them, those living in the most rural settings, realising this imagined future would entail geographical movement; it presupposed spatial mobility. Their opportunities to realising a social position would be affected by the opportunity structures they related to, by their perceptions of the opportunity structure, and by their capital dependent space to act upon and take advantage of it. For some of them, the opportunity structure represented obstacles that were hard to overcome, making the educational route difficult. Others of our interviewees described imagined futures that included a rural lifestyle and staying in their home place. For them, there were other forms of obstacles, mainly having to do with work opportunities and with the realism behind securing a livelihood in a rural community. The challenge for the educational system is to open up for and to support different forms of imagined futures. To the extent the education system today promotes a certain type of disembedded, individualised, alone standing figure, as claimed by, for example, Corbett (2016), it needs to include alternative imagined futures in its repertoire.

References

Bæck, U.-D. K. (2015). Rural location and academic success. Remarks on research, contextualisation and methodology. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 59: 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2015.1024163

Bæck, U.-D. K. (2004). The urban ethos. Locality and youth in North Norway. Young. Nordic Journal of Youth Research, 12(1): 31-47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308804039634

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook for the theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241-258). New York: Greenwood Press.

Butler, T. & Hamnett, C. (2007). The geography of education: Introduction. Urban Studies, 44(7), 1161-1174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980701329174

Byrhagen, K. N., Falch, T. & Strøm, B. (2006). Frafall i videregående opplæring: Betydningen av grunnskolekarakterer, studieretninger og fylke (Dropout from upper secondary education. The significance of grades, study programs and county). Nifu.

Cloward, R. A. & Ohlin, L. E. (1960). Delinquency and opportunity; a theory of delinquent gangs. Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press.

Corbett, M. (2007). Learning to leave: The irony of schooling in a coastal community. Black Point, NS: Fernwood Publishing.

Corbett, M. (2016). Rural futures: Development, aspirations, mobilities, place, and education. Peabody Journal of Education, 91, 270-282. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2016.1151750

Cuervo, H. & Wyn, J. (2012). Young people making it work: Continuity and change in rural places. Carlton: Melbourne University Press.

Falch, T. & Nyhus, O. H. (2009). Frafall fra videregående opplæring og arbeidsmarkedstilknytning for unge voksne (Dropout from upper secondary education and labor market connection for young adults). Nifu.

Farrugia, D. (2016). The mobility imperative for rural youth: the structural, symbolic and non-representational dimensions rural youth mobilities. Journal of Youth Studies, 19(6), 836-851. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2015.1112886

Green, B. & Corbett, M. (2013). Rural education and literacies: An introduction. In B. Green & M. Corbett (Eds.), Rethinking rural literacies: Transnational perspectives (pp. 1-13). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137275493_1

Hargreaves, L., Kvalsund, R. & Galton, M. (2009). Reviews of research on rural schools and their communities in British and Nordic countries: Analytical perspectives and cultural meaning International Journal of Educational Research, 48, 80-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2009.05.002

Hoëm, A. (1976). Yrkesfelle, sambygding, same eller norsk? Oslo, Norway: Universitetsforlaget.

Hoëm, A. (2010). Sosialisering - kunnskap - identitet (Socialisation – knowledge – identity). Oslo: Oplandske Bokforlag.

Kalaoja, E. & Pietarinen, J. (2009). Small rural primary schools in Finland: A pedagogically valuable part of the school network. International Journal of Educational Research, 48, 109-116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2009.02.003

Knickle, S. (2014). Buried treasures: An institutional ethnography of small school closures in rural Nova Scotia. (MA), Acadia University, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Lee, M. (2014). Bringing the Best of Two Worlds Together for Social Capital Research in Education: Social Network Analysis and Symbolic Interactionism. Educational Researcher, 43(9), 454-464. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X14557889

Lie, I., Bjerklund, M., Ness, C., Nygaard, V. & Rønbeck, A. E. (2009). Bortvalg og gjennomstrømming i videregående skole i Finnmark. Analyser av årsaker og gjennomgang av tiltak (Throughput in upper secondary education in Finnmark county). Alta, Norway: Norut.

Markussen, E. (2016). De’ hær e’kke nokka for mæ. Om hvorfor så mange ungdommer i Finnmark ikke fullfører videregående opplæring (This is not for me. About why so many young people in Finnmark do not complete upper secondary education). In K. Reegård & J. Rogstad (Eds.), De frafalne. Om frafall i videregående opplæring (pp. 154-172). Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk.

Svensson, L. (2006). Vinna och försvinna? Drivkrafter bakom ungdomars utflyttning från mindre orter (Win or disappear? Forces behind young people’s mobility from small places). Linköping, Sweden: Linköping Studies in Education and Psychology No. 109.

Tiller, T. (1990). Kenguruskolen: Det store spranget. Vurdering basert på tillit (The kangaroo school. The big leap). Oslo: Gyldendal.