NJCIE 2019, Vol. 3(1), 51-68

http://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.3332

Discrepancies in School Staff’s Awareness of Bullying: A Nordic Comparison

Ingunn Marie Eriksen[1]

Senior Researcher, Norwegian Social Research, Oslo Metropolitan University

Lihong Huang

Research Professor, Norwegian Social Research, Oslo Metropolitan University

Abstract

Bullying is a severe problem for school students in many education systems. We know that the role of principals and teachers is vital for detecting and following up on bullying, and for implementing appropriate measures. Staff awareness of bullying in schools is commonly reported to be far lower than students’ own reports, but this is rarely studied from a comparative perspective. This study assesses reported bullying from the perspectives of students, teachers and principals in schools in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. We examine the association between the school administration’s awareness of bullying among their pupils, student reports of bullying, and the information and measures put in place at schools in each country. We use comparative analyses of the International Civic and Citizen-ship Education Study (ICCS 2016) data from Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden (students, N = 18,962; teachers, N = 6,119; school principals, N = 630). The prevalence of students’ reports of bullying are similar across the four countries, but we find large discrepancies in the prevalence of bullying re-ported by students, teachers and principals. Whereas Norwegian schools are most active in employing measures to inform and raise awareness about bullying for staff, parents and students, Finnish teachers and principals were observed to be far more aware of their students’ bullying than their Nordic counter-parts.

Keywords: school bullying; whole school approach; students; teachers; principals

Introduction

School bullying is associated with severe mental health problems, learning difficulties and dropping out of school; it has both short-term and long-lasting negative effects (Arseneault et al., 2010; Tan et al., 2017; Zarate-Garza et al., 2017). It may also increase the risk of suicide among students (Mossige et al., 2016). The need to prevent bullying is vital not only for the minority that are directly involved, but also for the whole community, as even witnessing peers being bullied poses a risk to bystanders’ mental health (Rivers et al., 2009). Educators’ involvement in preventing bullying is crucial. They can prevent bullying by fostering a positive relationship between pupils through authoritative management (Huang et al., 2015) and through attempts to arouse the bully’s empathy for the victim (Garandeau et al., 2016). Educators are in a key position to intervene when bullying occurs (Flaspohler et al., 2009; Veenstra et al., 2014). In order to stop school bullying, it is therefore vital that adults are aware of the bullying in the first place. Bullied pupils telling adults in school about their experiences is the strongest predictor of teacher involvement in stopping bullying (Novick & Isaacs, 2010). Moreover, as bullying mostly happens in areas where adults are not present (Fekkes et al., 2004), informing teachers about any bullying that occurs may be the only way that adults receive knowledge of it.

However, students often do not report their experiences of bullying to adults at school (Fekkes et al., 2004; Wendelborg, 2018). Previous research has identified several factors that prevent students from reporting incidents related to bullying: these include the shame associated with being victimised by peers (Eriksen & Lyng, 2018b; Strøm et al., 2018); the lack of trust that the teacher will be able to stop (rather than aggravate) the bullying; and the fear that adults’ responses will be ineffective or insensitive, and that peers will respond negatively to those who disclose that bullying is occurring by worsening or increasing the frequency with which students are bullied (Oliver & Candappa, 2007). That much bullying goes unreported is also due to the fact that knowledge about the occurrence of bullying varies between students, educators and parents (Ramsey et al., 2016; Totura et al., 2009), and that students, teachers and principals do not necessarily regard bullying in the same way, even when they are working with the same definition (Eriksen, 2018).

Gaining insights into different perspectives of bullying within the same school is vital in order to assess the level of information exchange between pupils, teachers and principals, as well as to analyse how much bullying goes undetected and unchecked. However, most studies measure bullying from only one perspective (Ramsey et al., 2016), and only a few studies have focused on differential perceptions of bullying held by students, parents and adults (Newgent et al., 2009). Moreover, although a comparative education perspective is important in order to assess international similarities and differences, international comparisons are few and difficult to make due to a lack of comparable data; bullying may have both similar and different meanings and consequences across cultures (Guillaume & Funder, 2016). In this paper, we investigate reported bullying from the perspectives of students, teachers and principals, and whether there are national differences in how much bullying goes undetected by school staff in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden, using data from the 2016 International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS). We also consider how different reports of bullying may relate to the amount of information measures that the school implements.

Previous estimations of the prevalence of bullying in Nordic countries

Nordic countries share some characteristics in their social and political systems, as well as in their high levels of social and economic development as measured by the Human Development Index (HDI). There are high levels of gender equality and low levels of social inequality. Despite their similar education systems and policies, most international studies indicate that Nordic countries differ in terms of pupils’ achievements. (This was not the case in the ICCS 2016 study, which showed that Nordic pupils were close to each other and among the top performers [Schulz et al., 2018]). However, reports on bullying in the Nordic countries are often contradictory. One study of parental reporting of school bullying (with data from 1984 and 1996) found that the highest rate of bullying by far was found in Finland, where 22% of parents reported bullying, whereas the rates in other Nordic countries were significantly lower (Nordhagen et al., 2005). Another large-scale study conducted in 1997–1998 compared bullying and health-related outcomes in 28 countries and showed that the lowest prevalence of frequent bullying (i.e. a few times or weekly), during the current semester, was observed in Sweden (5.1% for girls and 6.3% for boys). There were higher rates in Finland (9.2% for girls and 12.5% for boys) and Norway (10.6% for girls and 15.3% for boys), whereas Denmark had the highest prevalence (24.2% for girls and 26.0% for boys; Due et al., 2005). PISA 2015 (OECD, 2017) showed that student reports of being bullied (any type) at least a few times a month were significantly higher in Denmark (25.4%) than in Finland (16.7%), Norway (17.7%) and Sweden (17.9%; Figure III.1.3, Part 2/2, p. 47). Although Norwegian students score highest on civic knowledge among the Nordic countries (Schulz et al., 2018), the ICCS 2016 study results showed that the prevalence of student reports of verbal bullying (at least once during the previous three months) was highest in Norway (56%) and lowest in Finland (42%). Meanwhile, the prevalence of physical bullying that occurred at least once in the past three months was 12% in Denmark, 15% in Finland, 18% in Norway, and 16% in Sweden (Table 6.7, p. 157).

Although these studies show different rates of bullying in the Nordic countries, they employ different definitions and measures, thus making it difficult to compare results. It is, however, likely that there are cultural differences that play out both in terms of how each country perceives acceptable levels of bullying, and in students’ reports and responses to bullying (Smith, 2016). As reporting of bullying, as well as international comparison, is fraught with inaccuracies (Guillaume & Funder, 2016), internal comparison is key to addressing possible discrepancies. There is a need for a more rigorous approach in comparing staff awareness of bullying internationally, particularly because discrepancies between accounts from students and staff may indicate that bullying is being overlooked and that students are not getting sufficient help.

Data and methods

We conducted secondary analysis on data from the ICCS 2016 study. ICCS 2016, initiated by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA), aimed to investigate the ways in which students in lower secondary schools around the world are prepared to undertake their roles as citizens (Schulz et al., 2018). The ICCS study collected data through three separately administered questionnaire surveys from three groups of participants: students in the 8th grade (or 9th grade in Norway), teachers, and school principals (Schulz et al., 2018). The ICCS study applied a sampling strategy to ensure representativeness of the data and comparability of data across countries. For each participating country, the ICCS data have a two-level structure with individual students nested within classes/schools. Each national sample that satisfied the participation standards set by the IEA was equally weighted to ensure international comparability (Köhler et al., 2018).

Table 1: Descriptions of the data used in the analyses

|

|

Denmark |

Finland |

Norway |

Sweden |

Total |

|

Number of schools |

185 |

179 |

148 |

155 |

669 |

|

Number of school principal participants |

175 |

172 |

142 |

141 |

630 |

|

Number of teacher participants |

489# |

2097 |

2010 |

1542 |

6138 |

|

Number of student participants |

6254 |

3173 |

6271 |

3264 |

18962 |

|

Average age of students |

14.9 |

14.8 |

14.6 |

14.7 |

14.8 |

|

% of female students |

51.3 (0.8) |

47.4 (1.1) |

49.5 (0.6) |

49.3 (1.0) |

49.4 (0.4) |

# Participation rates for the teacher survey were below the ICCS 2016 study standard of the minimum acceptable response rate of 80% in Denmark.

Table 1 presents the descriptions of data used in our analyses, which included 18,962 students with an average age of 14.8 years old, as well as 630 school principals and 6,138 teachers from 669 schools in four Nordic countries.

Variables of interest

We used data collected from student, teacher and school principal responses to questions about bullying. Students were asked the following question: “During the last three months, how often have you experienced the following situation at your school?”, with response alternatives of ‘never’, ‘only once’, ‘two to four times’ and ‘five times and more’. Students were then asked to provide their responses to six items: 1) “A student called you by an offensive nickname”, 2) “A student said things about you to make others laugh”, 3) “A student threatened to hurt you”, 4) “A student broke something belonging to you on purpose”, 5) “You were physically attacked by another student”, and 6) “A student posted offensive pictures or text about you on the Internet”.

For the school principals and teachers, the equivalent question was preceded by a definition: “Bullying is defined as the activity of repeated, aggressive behaviour intended to hurt someone either physically, emotionally, verbally or through internet communication”. This definition was followed by asking: “During the current school year, how often have any of the following situations happened at this school?” Principals and teachers responded ‘never’, ‘less than once a month’, ‘1–5 times a month’ and ‘more than 5 times a month’ to 6 items: 1) “A student reported aggressive or destructive behaviour by other students”, 2) “A student reported that he/she was bullied by a teacher”, 3) “A teacher reported that a student was bullied by other students”, 4) “A teacher reported that a student helped another student who was being bullied”, 5) “A teacher reported that he/she was bullied by students” and 6) “A parent reported that his/her child was bullied by other students”. Teachers were asked to respond to two additional questions: “A student informed you that he/she was bullied by another student” and “You witnessed student bullying behaviour”.

The principals were asked another question: “During the current school year, are any of the following activities against bullying (including cyberbullying) being undertaken at this school?” The principals responded ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to 8 items: 1) “Meetings aimed at informing parents about bullying at school”, 2) “Specific training to provide teachers with the knowledge, skills and confidence to make students aware of bullying”, 3) “Teacher training sessions on safe and responsible internet use to avoid cyberbullying”, 4) “Student training sessions for responsible internet use to avoid cyberbullying”, 5) “Meetings aimed at increasing parents’ awareness of cyberbullying”, 6) “Development of a system to anonymously report incidents of cyberbullying among students”, 7) “Classroom activities aimed at increasing students’ awareness of bullying”, and 8) “Anti-bullying conferences held by experts and/or by local authorities on bullying at school”.

Analysis method

We present the results of our analyses in three steps. In the first step, we report descriptive analyses of student reports of bullying across the four countries, but only on incidents that happened two or more times over the previous three months. These fall into four categories: 1) verbal bullying (or harassment, including name calling and teasing), 2) threats and intimidation (including threatening to hurt someone and breaking personal belongings), 3) physical attacks, and 4) bullying on the Internet. We also report the prevalence of bullying by the sum of the four categories and test the differences between genders. In the second step, we present the prevalence of principal reports of bullying in the current school year and compare it with teacher and student reports of bullying. In the third step, we investigate the relationships between the prevalence of bullying reported by students, teachers and principals and anti-bullying initiatives taken at schools. We present results by country and all four countries in comparison with each other, applying total weights at student level or school level whenever the analysis warrants. We applied a t-test, using standard errors to calculate significant differences between genders and between countries.

Result 1: Student-reported bullying in the Nordic countries

Table 2 presents the trends associated with student reports of four forms of bullying or harassment that occurred two or more times over the previous three months, as well as presenting a sum of bullying victimisation across five groups of students. As the most common form of bullying at school in all countries, the prevalence of verbal bullying (or harassment) is nearly the same in Denmark (40.9%), Norway (40.8%) and Sweden (40.7%), whereas the prevalence in Finland (35.9%) is significantly lower than in the other three countries.

Less common forms of bullying at school in all countries include student reports that they were being threatened by someone, which either meant that they were experiencing verbal threats that they were going to be hurt, or that personal belongings were broken on purpose by others. The prevalence of this behaviour is higher in Norway (11%) and Sweden (10.8%) than in Denmark (8%) and Finland (7.5%). Another less common form of bullying, experiencing bullying on the Internet, has a fairly similar prevalence rate across all four countries (3.4% in Denmark, 3% in Finland, 4.3% in Norway and 3% in Sweden). Although they are the least common form of bullying in all four countries, physical attacks have a significantly higher prevalence among Norwegian students (5.8%) and Swedish students (4.7%) than among Finnish students (1.8%).

Table 2 also shows that the total prevalence of students experiencing any form of bullying is 42.8% in Denmark, 37.3% in Finland, 42.2% in Norway and 42.9% in Sweden.

Table 2: Student responses of ‘twice or more times’ to the question “During the last three months, how often have you experienced the following situations at your school?” (Percent)

|

|

Denmark |

Finland |

Norway |

Sweden |

||||||||

|

Total |

Boy |

Girl |

Total |

Boy |

Girl |

Total |

Boy |

Girl |

Total |

Boy |

Girl |

|

|

Verbal bullying (or harassment)* |

40.9 |

48.6 |

33.5 |

35.9 |

42.9 |

28.3 |

40.8 |

44.6 |

37.1 |

40.7 |

45.1 |

36.3 |

|

Threats of being hurt and breaking of personal belongings on purpose* |

8.0 |

11.4 |

4.8 |

7.5 |

11.3 |

3.3 |

11.0 |

14.2 |

7.8 |

10.8 |

14.2 |

7.2 |

|

Physical attacks* |

3.5 |

7.8 |

1.6 |

1.8 |

9.6 |

1.6 |

5.8 |

10.5 |

3.7 |

4.7 |

11.1 |

3.2 |

|

Bullying on the Internet^* |

3.4 |

3.1 |

3.7 |

3.0 |

3.5 |

2.5 |

4.3 |

4.2 |

4.5 |

3.0 |

3.8 |

2.2 |

|

Sum: Victimisation of any form of bullying* |

42.8 |

53.7 |

38.2 |

37.3 |

46.6 |

29.7 |

42.2 |

50.0 |

39.6 |

42.9 |

51.5 |

41.1 |

|

Sum: No victimisation of bullying |

57.2 |

48.9 |

65.2 |

62.7 |

55.0 |

70.9 |

56.8 |

52.2 |

61.4 |

57.1 |

52.0 |

62.3 |

*indicates that a gender difference is significant at the 0.05 level where there are disproportionally more boys than girls in the group; ^*indicates a gender difference is significant at the 0.05 level only in Sweden.

The gender difference underlying bullying experiences is significant: boys are represented disproportionally more frequently in nearly all bullying victimisation groups, except in cases of cyberbullying, where the gender difference is only significant in Sweden. Girls are significantly less likely to experience bullying at school than boys across all four countries.

Result 2: School principal and teacher reports of bullying

To what extent are principals aware of school bullying? Table 3 shows the percentages of school leaders and teachers who had received reports of bullying in the current school year. Firstly, teachers are less aware of (i.e. they reported fewer) bullying incidents than principals in all four countries; this may be partly explained by the fact that principals view the entire school from an organisational perspective, whereas teachers view the school from a class perspective. Secondly, principals and teachers in Finland are significantly more aware of (i.e. there were more reports of) bullying that has occurred at school when compared with their counterparts in all three other Nordic countries. Thirdly, for the principals in all four countries, most bullying between students was reported by either a student, a teacher or a parent. Fourthly, although teacher reports of bullying largely follow the same pattern as those of principals, teachers in Finland reported the highest rates of witnessing student bullying at school; only 12.4% of Finnish teachers responded that they had ‘never’ witnessed student bullying behaviour at school, whereas teachers in Norway reported the lowest rates, 66% responding that they had ‘never’ witnessed bullying.

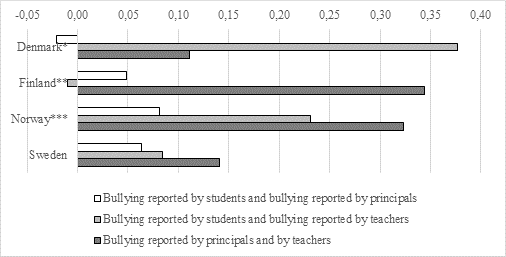

There is no significant correlation between student and principal reports of bullying at the school level in all four countries, as shown in Figure 1. Although no significant correlation is found in Sweden, we find a significant correlation between the bullying reported by students and that reported by teachers in Denmark and Norway. Further, we also find a significant correlation between bullying reported by principals and that reported by teachers in Finland and Norway.

Figure 1: Correlation coefficients between student, teacher and principal reports of bullying

Note:

*The correlation is significant between bullying reported by students and

bullying reported by teachers. **The correlation is significant between

bullying reported by principals and bullying reported by teachers. ***The

correlation is significant between bullying reported by students and bullying

reported by teachers, and the correlation is significant between bullying

reported by principals and bullying reported by teachers.