NJCIE 2019, Vol. 3(4), 18-33

http://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.3491

Nurturing global consciousness through internationalization

Mette Birgitte Helleve[1]

Ph.D. Candidate, Oslo Metropolitan University

Peer-reviewed article; received 30 January 2017; accepted 03 July 2017, published in Norwegian in Vol 1, issue 1. Translated from Norwegian to English, accepted for publication 23 August 2019.

Abstract

The topic of this article is nurturing global consciousness through internationalization in teacher education. As a teacher educator, I have been supervising 29 student teachers in their three-month practice in Namibia and Uganda over a four-year period. Here I have focused on the students' experience according to global consciousness with a primary focus towards their global sensitivity. The purpose of this article is threefold. First I describe the nuances of global consciousness and the connection between the three sub-areas: global sensitivity, global understanding, and global self-representation. The two concepts intersubjectivity and attunement will provide a meaningful contribution to the definition of global consciousness. Secondly, I argue that internationalization, as a three-month-long practice abroad in itself, is not sufficient to nurture global consciousness. Thirdly, I describe a pedagogical approach to nurture teacher students’ global consciousness through a set of five different tasks. The research question for this article is: How can initial teacher education contribute to nurturing student teachers’ global consciousness through mentoring and practice abroad? Methodologically the study is grounded in a phenomenological tradition. In the analysis of the material, I have focused on the students' experiences concentrated toward the concept of global consciousness and the sub-areas mentioned above.

Keywords: internationalization in teacher education; global consciousness/sensitivity; attunement; inter-subjectivity; how to nurture global consciousness

Introduction - Internationalization in teacher education

Internationalization of higher education in the sense of international cooperation and mobility has increased in scope. This is reflected in efforts to strengthen the internationalization of higher education in Norway, including teacher education (Ministry of Education, 2007, p. 38; Ministry of Education, 2009a, p. 26; Ministry of Education, 2009b, pp. 5-11, 44-54). The concept of internationalization is understood as internationalization at home and internationalization abroad.

Internationalization at home emphasizes activities and study offers to develop international and intercultural understanding. Internationalization abroad includes all kinds of education beyond the mother country’s own borders: mobility, cooperation on education programs and implementation of these.

Internationalization is the exchange of ideas, knowledge, goods, and services between nations over established land boundaries and consequently has the individual country as a standpoint and perspective. Within education, internationalization is the process of integrating an international, intercultural and global dimension in goals, organization, and action. The White Paper nr. 14 (2008-2009) Internationalization of education defines internationalization of education as follows:

«The process of integrating an international, intercultural and/or global dimension into the purpose, functions or delivery of post-secondary education».

In Norwegian teacher education, student exchange is considered as the most visible form of internationalization. Efforts are made to increase research collaboration between the institutions and offer a student to stay in a larger academic cooperation (Leming, Nedberg & Rotvold, 2012; Nilssen, 2015). In recent years, in line with political goals, there has been an increasing number of students studying abroad for part of their education (Duncan, 2014). In the Report to Stortinget (Parliament) no. 11 (2008-2009), The teacher. The role and Education, increasing internationalization is, among other things, promoted as a strategy to educate teacher students with cultural understanding, global consciousness and solidarity (Ministry of Education, 2009a, pp. 26-29).

In this article, I will highlight the term global consciousness, which consists of the three subareas: global sensitivity, global understanding, and global self-representation, as well as the two concepts attunement and intersubjectivity.

As part of internationalization, teacher students in Norway can take part of their education abroad, both inside and outside Europe, including parts of their field practice. Some teacher education institutions offer internships abroad. In this article, I will investigate the relationship between internationalization as an internship abroad in the global south and the development of global consciousness. The purpose of nurturing the students' global consciousness is to prevent the practice of Norwegian teachers' students in the global South from becoming a form of western tourism. Santoro (2014) has found in her research, that internationalization is in danger of leading to just that. She writes: "Tourism is an expression of privilege, both financial and social. It is the tourist who travels to observe the non-white and exotic 'Other' and who chooses what cultures are worthy of their attention '(Santoro, 2014, p.434). The challenges raised by Santoro (2014) concern all those involved in the internationalization of higher education. There have been raised critical questions about how internationalization can easily cause the development of asymmetry where the Western world becomes a premise provider that dominates the global education discourse (Storeng, 2001). These perspectives are also raised by Biesta (2013) in his research related to cooperation and communication in an international context where he claims, that the meeting between nations, cultures, and traditions can pose a risk of colonization, where agents with power push their way of thinking and acting on those who are weaker (Biesta, 2014, p. 173).

In line with Biesta, I would argue, that in the same way as education in general, internationalization cannot be regarded as a mechanical device. On the other hand, I suggest that we rather consider internationalization as a weak connection between communication and interpretation, interference and response (Biesta, 2014, p. 26), where those who participate in an internationalization process, will be challenged in terms of both global sensitivity, global understanding, and global self-representation. These are challenges that concern all those who are involved in the internationalization of higher education. Aiming at nurturing teacher students global consciousness through internationalization, this study is based on the following research question:

How can teacher education nurture the student’s global consciousness through mentoring and field practice abroad?

I consider the answers to this question as a contribution to strengthen the work of internationalization in future teacher education. Notably, as a starting point for didactic considerations, both in terms of form, content and pedagogical working methods.

Global consciousness as an intersubjective process

Global consciousness is in this article, regarded as an intersubjective process. This means that the term will appear as a pedagogical-psychological value and category more than a political-geographical concept. Being global conscious is about being sensitive, registering and having an understanding of events both inside and outside ourselves. The term intersubjectivity is relevant for capturing the understanding of global consciousness as a relational matter. To support the understanding and refining of the concept of global consciousness, the term "attunement" will be used.

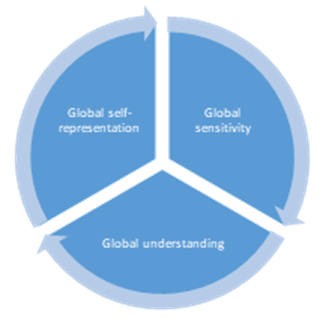

In order to capture the complexity of the concept of global consciousness, I will define the three sub-areas: global sensitivity, global understanding, and global self-representation. According to Mansilla and Gardner (2007), these three areas represent the content of the concept of global consciousness (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Model of Global Consciousness

Source: Inspired by Mansilla and Gardner (2007)

Global sensitivity

Our global sensitivity is linked to human sensitivity to objects in our vicinity that we meet, whether it is other people, landscapes, places, music, culture, etc. In order to nuance the content of the concept of global sensitivity, the notion of attunement will be highlighted. This is because I believe the term can contribute to explaining how we through conscious attention directed at one's own and others' attunement can strengthen our global sensitivity.

The term attunement (in German stimmung) is referred to in English literature as either attunement or mood. In this context, the term refers to the fact that man's relational contact with the world is not neutral but attuned (Heidegger, 1927/2007; Løgstrup, 1983). This in the sense that our immediate experiences, our perception of the world, are brought back to our existence. We are attuned by our relation to the surroundings and not by the surroundings itself. The mind cannot exist without being attuned by everything we meet. Our senses are attuned uninterruptedly, although we are not always aware of the attunement that is awakened in us. We cannot immediately characterize the attunement because it is unconscious to us. It is only in retrospect that we can recognize our attunement if we try to recall it. Attunement is a prerequisite for human emotional life (Løgstrup, 1983). Our attunement gives resonance to our emotions. In this attuned sensation lies the source of all personal expressions. We are already attuned by previous experiences when we find ourselves in new situations (Løgstrup 1983, p. 16). Attunement is associated with the individual's attention to how the person is attuned in the encounter with nature, life, and other people, as in this context, during a practice period. Among other things, it is by focusing and being aware of one's own attunement that the individual can consequently see, experience and recognize the other person’s attunement (Løgstrup, 1983). I believe, stimulating global sensitivity is closely linked to getting in touch with one's own attunement and then recalling the attunement through dialogue with others. Later in this article, I will show how one through various mentoring tasks, a person can recall their own attunement, and thus stimulate, and strengthen their own global sensitivity.

Global understanding

Global understanding can be associated with both confusion and wonder over the great complexity we are part of. This confusion and wonder can help construct knowledge and understanding of relationships in our global world (Mansilla and Gardner, 2007). In this case, it is about schooling and teaching in Namibia and Uganda seen in a historical, cultural and political light. Global understanding in this context is about the students' understanding of themselves both as global observers and global agents. An understanding that again requires self-reflexivity and forms the basis for the students' global self-representation.

Global self-representation

Global self-representation is associated with the individual's understanding of themselves as agents in a global context. By adjusting for and from others, we build up a register based on previous experiences. Such a register helps us know how to grasp a situation and how we can be consistent with what we want to be together with others (Mansilla and Gardner, 2007). Being a Norwegian student teacher, in the middle of a practice period, with a responsibility for teaching in a class in Namibia or Uganda, is associated with many actions that require the students to act as reflective agents. A task that requires students to have control over their own and others' attunement. An attunement that gives direction to the student's actions in the meeting with the pupils, the other teachers, and the school management. In this way, constructing global self-representation is closely linked to attunement, global sensitivity, and global understanding. This to the extent that the three sub-areas appear to be mutual preconditions for each other and thus together form the crucial substance of the concept of global consciousness.

Intersubjectivity

In the context of global consciousness and intersubjectivity, I understand intersubjectivity as a meeting place where the individual ceases to be an isolated individual, but one who meets himself and the world through others. Intersubjectivity is about creating relational contact, where experience, body, and emotions are in focus. Intersubjectivity, as a concept, has been widely discussed within phenomenology and existence philosophy (Honneth, 2000; Schibbye Løvlie, 2002; Wind, 1998). In addition, intersubjectivity has been a topic in parts of psychological development theories. The term is phenomenological anchored and describes something we immediately recognize as central and meaningful in our lives. The dialogic nature of humankind displays itself in the intersubjective meeting place promoting the social and dyadic rather than the subjective and individual (Mead, 1934; Vaage, 2001).

The theoretical foundation for this study is based on the recognition that we all exist as mutual preconditions for each other. The moment Norwegian teacher students meet a school pupil in Uganda and they spend time together, they are no longer just individual, separate bodies. They suddenly appear as individuals in the light of each other. A realization that presupposes thinking individual and community, simultaneously and mutually. Both Hegel (Honneth, 2000) and Mead (1934) inspire this point of departure. In both of them, the main claim is that the intersubjectivity constitutes subjectivity. Hegel's concept of recognition is about the human self and the elimination of the distance between sociality and individuality (Schibbye Løvlie, 2002; Wind, 1998). In recognition, man ceases to be an isolated individual, but a self that meets himself and the world through others. Mead, who has again gained inspiration from Hegel, considers the intersubjective as a meeting place where the individual meets the community with their own horizon of understanding and their own perspective on one side and the other's horizon of understanding and perspective on the other side. In the following quote, this claim is expressed: "We must be others if we are to be ourselves" (Mead, 1924/25, p. 292, in Vaage, 2001, 133). In light of the term intersubjectivity, all experiences are anchored both in interaction and in being able to take the other's perspective (Vaage, 2001). Both global sensitivity, global understanding and global self-representation presuppose an intersubjective room characterized by interaction and the ability and willingness to take the other's perspective.

Data material and method

The study is conducted among four groups of teacher students, a total of 29 students over four years (from 2012–2015) in connection with the teacher students' three-month internships in Namibia and Uganda respectively. All the 29 students, who were selected by the university to travel, answered positively at the request to participate in this study. Several of the students had international experience and had travelled extensively both to Africa, Asia, and South America. Everyone had an interest in internationalization and for some of the students, this interest has led to development studies, to others for studies in intercultural communication and religion, and to studying abroad through international organizations.

Various qualitative approaches to the study have been selected. The material of this study consists of the students' practice reports, logbooks, and a group interview. This in addition to field notes obtained from a three-day mentoring workshop. Here the students' experiences were discussed and elucidated through tasks focusing on the students' sensitivity and emotionality. These tasks will be explained in more detail below. The students' inter-subjective experiences and attunement appeared throughout the entire practice period. In the analysis of the material, I have coded, categorized and condensed based on the link between the emotions that the students have been in contact with during the course of practice and the three sub-areas of global consciousness: global sensitivity, global understanding, and global self-representation. When I have condensed the material, the following seven emotions have been the most dominant: frustration, love, uncertainty, impressiveness, joy, inadequacy and heart-felt or touched.

A phenomenological approach

In this study, I have examined the student teachers' experiences related to the phenomenon of global consciousness. The development of global consciousness is in this context regarded as a phenomenon that exists in the teacher students` at a pre-scientific level, constituted through human activity. Global consciousness awakens through human intentionality by the fact that our consciousness always is directed at something or someone. This makes global consciousness of both a subjective and an intersubjective matter. A matter I believe a phenomenological approach can capture. Phenomenology poses the simple question "What is it like to have a certain experience"? (Van Manen, 1982, p. 296). This question has formed the framework for the development of the five mentoring tasks and the analysis of this material.

The phenomenological analysis, based on coding, categorization, and condensation, is linked to global consciousness as a crucial dimension of the student's experiences as it appears in the material.

Ethical considerations

This study has required several ethical considerations linked to the fact that internationalization can lead to a form of western tourism when it is aimed at countries in the south. Our students in the north carry out their practice in countries south. We in the north ask for entry into schools and universities, often with little or no financial compensation for the partner schools involved. Meeting these considerations requires global consciousness. It requires that I, both as a researcher and as a supervisor, listen to my own tact and attunement and adjust myself accordingly. For example, it will mean listening and being responsive to our partners in Namibia and Uganda and working consciously to create symmetrical relationships based on mutual recognition and the fulfillment of both parts' wishes and expectations.

The confidentiality of this study is ensured by the names of people, schools and places being anonymized, and the teacher students having fictitious names. However, it is difficult to secure the confidentiality of the university that has sent the students. Although we do not use place names in Namibia and Uganda, this could be tracked. However, I do not consider it a problem since the experiences that have emerged through this study, as findings cannot harm schools/colleges, students, teachers, teachers or other participants.

To stimulate global consciousness

The actual implementation of the internship is certainly, what has stimulated the students' development of global consciousness the most. Including everything, that involves contact with both students, teachers, school leaders and parents in connection with the practice schools. In addition, the students have established contact with other young people, families, and friends who have not had any connection to the actual course of practice. Of course, these meetings have also marked and stimulated the students' global consciousness. As part of the work to nurture the students' global consciousness during their initial teacher education, all students took part in the pre-work placement in compulsory lectures on internationalization. Here the students were given an introduction to the historical, political and didactic context in both Namibia and Uganda. In the following, I will focus on the part of the internship where their initial teacher education has a direct impact on nurturing the students' development of global consciousness through contact-teacher visits and a workshop. In order to gain access to the students' intersubjective experiences, I have developed a mentoring structure that consists of five different tasks that stimulate global consciousness and thus all three sub-areas: global sensitivity, global understanding, and global self-representation. The purpose of the tasks was to facilitate the students to get in touch with their own attunement. During the workshop, the students were invited into a dialogue where their emotional experiences were in focus. Through these tasks, unconscious and conscious sides of the students' experiences were activated, which has resulted in a reconstruction of experiences. In the following, the five tasks will be briefly described.

Task 1–5:

1) The first day of the workshop was based on the didactic relationship model of Bjørndal and Lieberg (1978). As I did not know the students from before and they did not know me, I wanted to start with the didactic category - Participant assumptions. This was to give everyone an opportunity to tell each other a little about themselves and our motivation to participate in the internationalization of teacher education through practice in the South. This both because it was our first meeting, but also to create space to hear everyone's voices and thus create a common starting point for the group, where everyone has justification and everyone can feel safe. Secondly, we worked with the category - Aim. Here the purpose of the visit from the university was presented, the goal of internationalization, considering both the research goals and the more institutional overarching goals. Then we moved into the two categories - Content and Working methods. Here it became clear that the content and the working methods were prerequisites for each other. This is because, through the working method and in the dialogue, we would let the content appear. Secondly, we discussed the framework factors for the practice follow-up, where agreements on practice visits outside the schools came into place and the plan for mentoring was presented. As for the last didactic category - evaluation, we discussed how it would be two-fold, where one part of the evaluation was aimed at the actual workshop and the other part against this article as the final document.

2) Based on the five relational skills of cooperation, assertiveness, responsibility, empathy, and self-control derived from the CARES model of Gressham and Elliot (2002) [2], students were asked to rate themselves on a scale of one to six. Next, they were asked to connect each of the five skills to practice experience. In this way, the students moved from the associated experience to an analysis of the experience and thus to a higher degree of consciousness.

3) During the third tutorial exercise, the students were asked to find six emotions they had been in contact with during the internship. Next, they were asked to connect them to colors, i.e. to write the name of the emotion and find a color that they felt fit for it. Then they were asked to draw a circle on a piece of paper. They were told this circle should represent themselves. Subsequently, they should draw in the six emotions with six different crayons in the circle, so that the colors filled out the circle in a manner consistent with their experience. In this task, the students were given the opportunity to establish which emotions they had been in contact with during the internship for the purpose of stimulating their emotional consciousness.

4) The fourth exercise was designed as a home assignment. The students were given the task of writing their practice report based on the six emotions they had obtained during exercise three and then connecting the six emotions to didactic categories derived from the didactic relationship model (Bjørndal and Lieberg, 1978). The purpose of this task has been to give the students the opportunity to stick to the emotional side of their experiences during the internship. As an example, one student has made a connection between the emotion 'uncertain' and the didactic categories 'content' and 'participant assumptions'. He writes in his practice report:

As I have taught mostly social studies, I have reflected on the knowledge the textbooks convey. I thought this was very difficult when I taught the theme "Colonialism in Southern Africa". There was nothing about genocide and little about the consequences of colonization. This made me very insecure about what information they wanted the students to have and what I wanted to convey. The goals for each subject are clear and the textbooks are made after them. (Practice report - TB)

By connecting emotion and didactic categories, the student reconstructed his previous experiences creating a good starting point for further reflection and greater insight on both a personal and a professional level.

5) With the wish to use pictorial expressions, the fifth mentoring task began with art postcards. All participants[3] were asked to select a postcard that they thought made the best matched with their overall experience of the entire practice period. When everyone had chosen their postcard, they were asked to say why they chose this postcard. The purpose of this task was primarily to give all participants an opportunity to create new expressions in a way that was not predetermined. Through the postcards, the participants used words and formulations that they would not otherwise have used. This is because, in addition to their own perspectives, they were influenced by the pictorial expression of the various postcards. In this way, the participants took the postcard's perspective and made it their own in a new form.

Global consciousness and the students' reconstructions of their own experiences

In the following, I will first associate the students' emotional experiences with global sensitivity. Several of the student's experiences have triggered the feeling of frustration. The conception they had of teacher-pupil interaction as authoritarian and mechanical, most students found very frustrating. This was further reflected in the teaching, which they also describe as mechanical and instrumental. The pupils are seen as a group, not as individuals, and the pupils repeating after the teacher (rote learning) characterized the teaching. They also express frustration related to the teachers' time spent when students had to sit quietly at their desks for a long time without working on school subjects. The students' global sensitivity has been stimulated when it comes to disciplining. Seen with their Norwegian glasses, they found that the discipline in the schools was impeccable. However, they believed that in some contexts the teachers did not respect the students. For example, they draw on the teachers' late arrival as disrespectful to the students and point out that it provides little time for the learning work with the students. The frustrations they have felt can be summarized in the following quotation from Johanne:

The adult role and adult's view of children has been frustrating, and this frustration has again made me sad. As mentioned previously, the students are seen as a group and not as individuals. The teaching is therefore in many cases little pupil-oriented and the learning methods are often mechanical. Pupils are rarely explained why they should learn, what to do during the lesson, and what is expected of them. On several occasions, students were hit with a stick if the teacher thought they had inappropriate behavior, often without warning, and in situations where expectations were not clear. (Group interview - JH)

Several students describe being impressed as a significant feeling they experienced. This feeling of being impressed has been associated with meeting a school of limited material resources in the form of lacking learning materials, few books, and few desks. Gabi says, "Eventually, I got used to this and saw the opportunities in what was there, instead of focusing on what limited me" (Group Interview - GB). Anne points to the difficult life situations they were learning about, where a large number of children are orphans and several lacking adults taking care of them. She puts it like this:

Then I think of the enormous everyday challenges many of the other children have, those who come from homes where the parents are not present at all, where the parents are alcoholic, sick or dead. The children have so much more responsibility than children at home in Norway. (Group interview - AN)

She continues: "I am so impressed and touched and think that with such an effort, how much more they deserve to get out of school than they actually do". Several students underline the joy they have felt and express how they were inspired by what they experienced as a good atmosphere characterized by humor and laughter. They have also been amazed at the importance of getting together for a while every morning before teaching starts at 7 a.m. Marion says

This moment was something I really appreciated for it was such an encouraging and inspiring start to the day. The way the teachers talked about the students in the commentary on the Bible verse and in the prayer was magical and many times, I felt tears of joy at being in such a community. (Transcribed group interview - MA).

She continues;

[O]ften I get a bad conscience towards everyone else in the world who doesn’t have the opportunities we have at home. But by taking part in everyday life, you get to see so many qualities they have in their society that we don’t have at home and which we would like to have. (Transcribed group interview - MA)

Olivia tells how she is touched when she thinks about the pupils' background. Many students come from homes where parents cannot write or read, at least not in English, which is the teaching language in Namibia and Uganda. Books are scarce in many of the pupils' homes and the student assumes that some pupils probably only have the Bible as reading-material when the school day was over. She also shows how it touched her when a girl in one class came to school the day after her father was brutally killed.

When it comes to global understanding, the material states that students ask many questions about aspects of school life and teaching situations that differ from what they know from the practice they have had at home. They point out different understandings of what characterizes good teaching and that curricula operationalization depends on many factors that digress from what they themselves are familiar with. This has aroused the feeling of frustration, insecurity, and love. They express frustration considering all the linguistic challenges, lack of teaching aids and textbooks, pressured work situations and the inefficiency of time spent. In addition, they show the pressure on teachers to prepare students for upcoming exams. These matters govern the work in the classroom.

The use of English as a language of instruction has been a central theme for the students. Several have felt insecurity related to the language situation in Namibia and Uganda, where English is the official language and the language of instruction from fourth grade, while both countries have different local languages. The students are concerned with what they perceive as a mismatch between the pupils' mother tongue and the language of instruction in the school. Anne says: "Many times I thought I had explained something well, but then it turned out that they had not understood a thing" (Group Interview - AN). The students know the reason why things are as they are in Namibia and Uganda and they also understand the challenges for pupils, teachers, and parents. At the same time, they ask critical questions about how the learning situation for the pupils could be improved and even find creative solutions in their own teaching.

The textbooks' presentation of Namibian history also raised questions. Marion refers to the uncertainty she felt when teaching "Colonialism in Southern Africa". She experienced a conflict related to what information the school wanted the students to get and what she wanted to convey herself. She points out that in the sixth and seventh-grade textbooks, there was nothing about the Herero-Nama genocide, Namibian indigenous groups virtually wiped out by the German colonists in 1904-1908, or the many other consequences of the colonization. Like the other students, she was very concerned with this historical tragedy.

Despite the challenges presented above, many describe how they have experienced a feeling of love. Several of the students point to the feeling of love related to their practical experiences. "There are many small events throughout the period that have made me feel loved," says Anne (Group Interview - AN). Anne relates the feeling of love to the meeting with students and teachers, and especially to the pupils' life situations. She has experienced them as difficult and they have seemed overwhelming to her. At the same time, she says

I have learned a lot from this internship about myself and about the people around me. The whole experience in itself makes me want to mention this feeling. I'm glad that I’m going to be a teacher and I'm looking forward to it. (Group interview - AN)

When it comes to the last sub-category, global self-representation, the analysis of the material shows that students wonder how to deal with being foreign teacher-students, especially when they are confronted with difficult and challenging situations which challenge their ethical frame of reference. This wonder is part of being a reflective agent and is part of the process in which students construct their own self-representation. In the examples above, it appears that the students are particularly challenged on their self-representation when they have witnessed physical punishment, which all students have observed, even though the law in both Namibia and Uganda prohibits physical punishment. Johanne appears as a reflective observer and agent when she asks:

“Physical punishment in school is prohibited in Namibia, but what can I do as a white European teacher? What is my role in this? I have become a teacher because I am on the children's side, but I come here as a self-invited, guest. Is it right of me to start a commotion over something I observe?” (Logbook - JH)

Others reflect on how the observations and experiences they have made in practice have given a sense of uncertainty associated with their own prerequisites for being a teacher. Anne discovered that she was moving away from the teacher she had been in past practice periods. She experienced that the expectations of her as a person and as a class leader were unclear and said: "In some situations, I felt like I was moving away from the teacher I have been in previous practice periods". This underlines how Anne’s global sensibility and attunement affect her understanding of the situation she has become a part of. Through her attunement, she has been challenged by whom she chooses to be in the role of teacher.

Gunhild attaches her sense of inadequacy to several didactic categories when she describes the inadequacy she felt when it came to the tasks she was facing. She asked herself how to set up the teaching to meet the needs of all 45 students in the class so that everyone got the learning outcomes she wanted them to get. She says, "I often felt that I didn't reach all the students". She particularly points out how the language was a big challenge for all those involved. She also felt it a little awkward using English as a language of instruction. Her vocabulary was insufficient: "... which led me not be able to reach those pupils who needed closer and more specific explanations. This was confirmed when the classes had tests at the end of each theme".

Johanne, on the other hand, describes how she felt proud of how she dealt with the tasks and challenges she faced. However, this feeling of pride can also be linked to feelings such as joy, curiosity, coping, being touched and calmness as the students also describe. Johanne writes, "I have felt proud of myself, that I came down here, and about what I have learned and the challenges I have faced." She is proud to have spent much of her free time creating teaching activities.

I feel pride and have been touched by the commitment and warmth of the pupils, how well they accepted me and how willing to learn they were. This sense of pride also contributes to a sense of mastery – both my own and the pupils'. (Logbook - JH)

Conclusion

The analysis of the material shows that the students who have chosen to take their practice in Namibia and Uganda are curious about the world. They are keen to learn how others think to gain multiple perspectives on the world and their own society. They see themselves as young people who have learned a lot and understand more. This material shows that injustice in the world upsets the students, including the major differences they encounter in the education system. The questions students ask reflect a critical attitude to the past colonization and at the same time a fear of appearing as Western tourists. They asked many questions: How should they present themselves as teachers in the Namibian and Ugandan schools? What can they be for their Namibian and Ugandan pupils and colleagues? Overall, everyone wished to be an adult that the pupils could trust. They question the educational perspectives they encounter in everyday school-life and in the classroom. Students wonder about the adult-child relationships that they experience as authoritarian and disrespectful to pupils, but at the same time seeing teachers who engage, support, and care for the pupils. They relate these relationships to cultural and historical conditions, but they find it difficult to accept how things are. The especially because that the students are aware of that the Namibian (Ministry of Education, Republic of Namibia, 2009) and Ugandan (Ministry of Education and Sports, Republic of Uganda, 2011) curriculum expresses an intention for a pupil-centered school.

Based on the general experiences from the internships abroad and the complex teaching situation the students have been faced with, they raise many questions related to the work as a teacher in Namibia and Uganda, and to future work as a teacher in Norwegian schools. I cannot say for sure how the meeting with the diversity they have experienced related to culture, language, economic and material conditions during practice will affect their future work in a school in Norway. This question requires further research.

This study confirms previous research that argues that teacher education must be clearer on what goals it has for internationalization (Leming, Nedberg & Rotvold, 2012; Nilssen, 2015). Internationalization must be an integral part of teacher education where the purpose, and thereby the objective, is clear and reflected in the organization of the program and curricula, including plans for the practice. In particular, it is important to be clear about how students abroad should be followed up to achieve the goal. It is therefore regarded as a great advantage when the students' bachelor theses are linked to internships abroad. This requires that internationalization be institutionalized, both organizationally and academically, so that we avoid being caught in a neo-colonization trap where the internationalization takes place solely on the premises of the northern institutions. When a practice period is added to land in the global south, in this case, Namibia and Uganda, extra demands are placed on the teacher education institution's work on facilitating and following up the practice. This work requires international educational competence, contextual knowledge, and mentoring expertise. In practice, this will in many cases require collaboration between several professionals.

In conclusion, I return to the overall problem for this study: How can teacher education help to stimulate student teachers' global consciousness through mentoring and practice abroad? In response to the problem, I believe that the most important finding in this study is that when students conduct practicum in countries in the south they are left with significant and complex emotional experiences that require pedagogical follow-up both before, during and after the students' internationalization process.

Overall, all students have expressed their experience from the mentoring workshop as a strengthening of their global consciousness. Among other things, this is expressed in the quotation below where a student says the following about his workshop experiences:

I would argue that it is very important to send down representatives from the college to have a workshop with the upcoming students who are going down here. I also want to say that the content and method in the workshop was what made the experience so good. The stay down here has become more important because I have become conscious of my experiences, sorted impressions, been taken seriously, talked about what has been difficult and because I have become conscious of the cultural and historical context of Namibia and Namibian education history. (Log: Feedback at the workshop - AND).

Based on this study, I believe that students who conduct internationalization through practice in countries in the south need even closer follow-up than those who carry out their practice in Norway. The quotation above shows how the students emphasize the importance of getting guidance on-site during the practical period. This is in line with Biesta (2013), who claims that the presence of a teacher can bring something into the guidance situations that were not there before. This presence of a teacher in charge of student mentoring will be equally important in the development of global consciousness related to internationalization as well as in learning in any other form of teaching and guidance.

This study has shown that the following-up could be done by offering students the opportunity to participate in a mentoring workshop that is specifically aimed at stimulating the students' global consciousness through the three sub-areas: global sensitivity, global understanding, and global self-representation. This can advantageously take place both as part of the preparations for the practical training, along the way through following-up and mentoring on the practice site and as part of the reflection work after the internationalization.

References

Biesta, G. (2013). The beautiful risk of education. First published 2013 by Paradigm Publishers. New York: Routledge 2016.

Biesta, G. (2014). Utdanningens vidunderlige risiko. Oslo: Fagbokforlaget

Bjørndal, B. & Lieberg, S. (1978). Nye veier i didaktikken?: En innføring i didaktiske emner og begreper. Oslo: Aschehoug.

Duncan, E. (2014). Internasjonalisering av utdanning. Oslo: NUPI – Norsk utenrikspolitisk institutt. http://www.nupi.no/Skole/HHD-Artikler/2014/Internasjonalisering-av-utdanning

Elliott, S. N. & Gressham, F.M. (2002). Undervisning i sosiale ferdigheter: En håndbok. Oslo: Kommuneforlaget.

Heidegger, M. (1927/2007). Væren og tid. Århus: Forlaget Klim.

Honneth, A. (2000). Kamp om anerkjennelse. Oslo: Pax forlag.

Kunnskapsdepartementet (2007). Statusrapport for Kvalitetsreformen i høgre utdanning. (Meld. St 7 2007-2008). Hentet fra https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/Stmeld-nr-7-2007-2008-/id492556/

Kunnskapsdepartementet (2009a). Læreren. Rollen og utdanningen. (Meld. St 11 2008-2009). Hentet fra

https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/stmeld-nr-11-2008-2009-/id544920/

Kunnskapsdepartementet (2009b). Internasjonalisering av utdanning. (Meld. St 14 2008-2009). Hentet fra https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/stmeld-nr-14-2008-2009-/id545749/

Leming, T., Nedberg, A., & Rotvold, L. A. (2012). Praksis i utlandet – en mulighet for internasjonalisering i lærerutdanningen? Vurderinger og gjennomføring. Rapport. Tromsø: Universitetet i Tromsø: Universitetet i Tromsø, Fakultet for humaniora, samfunnsvitenskap og lærerutdanning. Institutt for lærerutdanning og pedagogikk.

Løgstrup, K. (1983). Kunst og erkjennelse. København: Gyldendal.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self and society. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Van Manen, M. (1982). Phenomenological pedagogy. Curriculum Inquiry, 12(3), 283-289. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.1982.11075844

Mansilla, V. B. & Gardner, H. (2007). From teaching globalization to nurturing global consciousness. I: M. Suarez-Orozco (Red.), Learning in the global era. International perspectives on globalization and education (s. 47-66). Berkeley: University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520254343.003.0002

Ministry of Education, Republic of Namibia (2009). The national curriculum for basic education. Lastet ned fra http://www.ibe.unesco.org/curricula/namibia/sx_befw_2009_eng.pdf

Ministry of Education and Sports, Republic of Uganda (2011). NCDC 2 – The aims of the new Lower Secondary curriculum. Lastet ned fra http://www.education.go.ug/files/downloads/NCDC%202-%20The%20aims%20of%20the%20new%20Lower%20Secondary%20curriculum.pdf

Nilssen, V. (2015). Praksis i utlandet – en stimulans til kraftfull refleksjon? Uniped, 38(02), 112-126.

Santoro, N. (2014). “If I’m going to teach about the world, I need to know the world”: developing Australian pre-service teachers’ intercultural competence through international trips. Race Ethnicity and Education, 17(3), 429-444. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2013.832938

Schibbye Løvlie A. L. (2002). En dialektisk relasjonsforståelse i psykoterapi med individ, par og familie. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Storeng. M. (2001). Giving learners a chance. Learner centeredness in the reform of Namibian teaching (Doktorgradsavhandling). Institute of International Education, Stockholm University, Stockholm.

Vaage, S. (2001). Perspektivtaking, rekonstruksjon av erfaring og kreative læreprossar: George Herbert Mead og John Dewey om læring. I: O. Dysthe (Red.), Dialog, samspel og læring. Oslo: Abstrakt forlag.

Wind, H. C. (1998). Anerkendelse: Et tema i Hegels moderne filosofi. Århus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag.