NJCIE 2020, Vol. 4(1), 43-65 http://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.3518

Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures: Reflections on Our Learnings Thus Far

Stein, Sharon[1]

Assistant Professor, University of British Columbia

Andreotti, Vanessa

Professor, University of British Columbia

Suša, Rene

Postdoctoral Researcher, University of British Columbia

Amsler, Sarah

Associate Professor, University of Nottingham

Hunt, Dallas

Assistant Professor, University of British Columbia

Ahenakew, Cash

Associate Professor, University of British Columbia

Jimmy, Elwood

Program Coordinator, Musagetes Foundation

Čajková, Tereza

Doctoral Researcher, University of British Columbia

Valley, Will

Senior Instructor, University of British Columbia

Cardoso, Camilla

Coordinator, Terra Adentro

Siwek, Dino

Coordinator, Terra Adentro

Pitaguary, Benicio

Community Researcher, Pitaguary Indigenous Community

Pataxó, Ubiraci

Community Researcher, Pataxó Indigenous Community

D’Emilia, Dani

Artist and Independent Researcher

Calhoun, Bill

Director, UNISERES

Okano, Haruko

Artist and Curator

Received 14 September 2019; accepted 04 March 2020.

Abstract

In this article, we reflect on learnings from our collaborative efforts to engage with the complexities and challenges of decolonization across varied educational contexts within the Americas. To do so, we consider multiple interpretations of decolonization, and multiple dimensions of decolonial theory and practice. Rather than offer normative definitions or prescriptions for what decolonization entails or how it should be enacted, we seek to foster greater sensitivity to the potential circularities in this work, and identify opportunities and openings for responsible, context-specific collective experiments with otherwise possibilities for (co)existence. Thus, we emphasize a pedagogical approach to decolonization that works with and through complexity, uncertainty, and complicity in order to “stay with the trouble.”

Keywords: decolonization, pedagogy, modernity, colonialism

Introduction

It has been eight years since Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang (2012) published their widely influential piece, “Decolonization is Not a Metaphor,” yet their argument “that the language of decolonization has been superficially adopted into education and other social sciences” (p. 2) appears as prescient as ever as decolonization has entered mainstream educational lexicon. For instance, many recent efforts to transform Canadian higher education are articulated under the heading of decolonization, while the Bolivian state has incorporated the objective of decolonization into its education laws. There are now entire conferences and scholarly books and journals devoted to the topic, and several educational institutions have undertaken efforts to examine their own historical complicity in racial and colonial violence. Growing interest in decolonization offers numerous opportunities to engage in substantive structural analyses and generate educational strategies for imagining and enacting different futures.

However, as Tuck and Yang point out, there is also an ambivalence that attends this growing popularity. They problematize the tendency to reduce decolonization to a metaphor, which collapses it into other social justice projects and offers the false promise that it is possible to transcend colonization “without giving anything up” (Jefferess, 2012). We also observe that decolonization is increasingly treated as a site and subject of consumption and accumulation, not only of material benefits, but also of knowledges, relationships, experiences, and even critique itself. Decolonial critiques have become a valuable currency within the intellectual, affective, relational, and material economies of mainstream Western educational institutions. Within these economies, people tend to seek solutions and alternatives to colonization within existing paradigms, regimes of property, and comfort zones. When this happens, colonial patterns of relationship and colonial habits of being are reproduced at the very moment they supposedly become unsettled. When efforts made under the umbrella of decolonization are re-routed back into the same desires and entitlements that produce colonization in the first place, the transformative possibilities and ethical responsibilities of decolonization are eclipsed, and decolonization itself becomes weaponized as an alibi to continue colonial business as usual. As a result of these circularities of critique, many decolonial possibilities and alternatives are pre-emptively foreclosed.

We write as part of the Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures collective, a group of researchers, artists, educators, students, and activists involved in research, artistic, and pedagogical experiments in education. We have written extensively about both the generative and harmful potential of engagements with decolonization (Ahenakew, 2016, 2019; Ahenakew, Andreotti, Cooper, & Hireme, 2015; Ahenakew & Naepi, 2015; Amsler, 2019; Andreotti, 2016; Andreotti, Stein, Ahenakew, & Hunt, 2015; Andreotti, Stein, Sutherland, Pashby, Suša, Amsler, & the Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures Collective; Jimmy, Andreotti & Stein, 2019; Naepi, Stein, Ahenakew, & Andreotti, 2017; Stein & Andreotti, 2016, 2017; Stein, 2017, 2019, 2020; Stein, Hunt, Suša, & Andreotti, 2017). In our research, teaching, community engagements, and other forms of cultural production and pedagogy, we do not offer normative definitions of decolonization, nor put forth prescriptive plans for action. Rather, we seek to facilitate the development of ‘radars’ for potential circularities and short-circuits, and to identify opportunities and openings for responsible, context-specific collective experiments that enact different kinds of relationships, and different possibilities for (co)existence, without guarantees.

In this pedagogical approach, we emphasize complexity, complicity, and uncertainty, and draw on multiple interpretations and dimensions of decolonial theory and practice – in particular, its ecological, cognitive, affective, relational, and economic dimensions. We undertake this work with a sense of humility, recognizing that our lives and livelihoods are underwritten by systemic, historical, and ongoing colonial violence. Thus, we can only “gesture” towards the direction of decolonization, and we will undoubtedly make mistakes in the process, for which we are also accountable. Yet these mistakes also offer important learning opportunities. In this article, we offer reflections on these learnings with the idea that they might be useful to other educators who not only adopt a decolonial orientation, but who are specifically committed to working with the discomforts, challenges, and contradictions inherent in this type of pedagogical practice.

We begin by reviewing our previous efforts to map theories of change in relation to decolonization, illustrating how social cartographies offer a pedagogical and creative, rather than descriptive and prescriptive, approach to decolonization. We then introduce a metaphor – “the house modernity built” – that we have been using and developing in different contexts to foster deeper intellectual and affective engagements with decolonial theories of change and their implications. After addressing how the tendency toward consumption, driven by colonial desires and entitlements, can manifest in any one of these theories of change, we contrast the potential circularities of desires premised on consumption with the yearning for different kinds of relationship and modes of existence, and emphasize the importance of speaking to that yearning while remaining aware of the ever-present traps of inherited colonial habits. Next, we review some of our efforts to engage ‘otherwise’ possibilities, introducing the In Earth’s CARE framework that addresses five dimensions of justice and well-being. We conclude with questions that can help equip us to analyze today’s numerous social, political, and ecological challenges at an intellectual level, and an accompanying set of affective and relational orientations that might enable us to ‘compost’ harmful habits of knowing, being, hoping, and desiring.

A note about context and collective authorship

Before we proceed, it is important to situate our work. Decolonial critiques teach us that place matters a great deal in the production of knowledge; it matters both in terms of the imprint of our physical geographies, and our social positions as knowledge producers. In this section, we briefly address these two dimensions in turn.

Most of our work has been focused in what is currently known as “the Americas” – especially Canada, the US, and Brazil. Just as some translation is needed between the different formations of colonialism across these contexts, it is also needed between the American and European contexts, and the Nordic context in particular. Having long been “unthinkable” in mainstream scholarship, the role of colonialism in the Nordic countries is a slowly growing area of critique that challenges narratives of Nordic benevolent exceptionalism. This includes a recent special issue of Scandinavian Studies that attempts to “shed light on the ways in which Nordic and Scandinavian histories and cultures are, in fact, colonial and postcolonial histories and cultures” (Höglund & Burnett, 2019, p. 2). Other recent scholarship advocates for the educational imperative to address both ongoing Nordic colonization of Indigenous Sámi peoples, and Nordic countries’ neocolonial relationships with regard to Global South nations (Eriksen, 2018a, 2018b).

We do not undertake translation of our work to Nordic contexts in an extended way in this text, because without being immersed in these other contexts, it is presumptuous to assume that we understand their “heterogenous forms of empire” (Höglund & Burnett, 2019, p. 11). We are unable to speak to relevant tensions and patterns, or identify possibilities for intervention. Instead we invite those who are situated within these and other contexts to determine whether or how the presented frameworks might be relevant for them (or not). This invitation is inspired by our own efforts to engage others’ decolonial practices as contextually-relevant examples that can offer important teachings, rather than as universally-relevant models that we should adopt and follow. Engaging with different examples can teach us about the difficulties of interrupting colonial habits, while also reminding us that alternatives are possible. This approach bypasses the pressure to identify with or defend a single preferred model for change. In this spirit, we offer reflections on our own learning as an example (rather than a model) for others to think with.

We also recognize the tensions of writing this piece as a collective “we” given that, even amongst ourselves as authors, we inhabit very different structural positions with regard to the racialized, classed, and gendered structures that we critique. “We” are not “equally responsible or capable, and are not equally called to respond” to colonial violence (Shotwell, 2016, p. 7), even as none of us is “innocent of power” (Mitchell, 2015, p. 91). Thus, rather than either try to auto-ethnographically represent our own diverse stories, or ethnographically represent the stories of the communities that we are a part of and/or work with, we take a reflexive but post-representational pedagogical approach that invites people to engage educationally with the collective tensions, complexities and possibilities that, in our experience, arise at the interface of different critiques, communities, and contrasting onto-metaphysics. In taking this approach, we seek to mobilize possibilities for engaging with decolonization that are not premised on political prescription or moral conviction. Instead, we offer an invitation to dig deeper (connect the dots to analyze the ‘bigger picture,’ and honestly face its implications), and relate wider (expand our capacity for social and ecological responsibility). These are pre-requisites for showing up differently for decolonizing work, without the common projections, fragilities, and overdetermined expectations. In general, we seek to prepare people to engage with different interpretations and dimensions of decolonization, but this looks different depending on their starting point, context, and social positionalities, among other things.

Thinking pedagogically using social cartographies

Every diagnosis of the present contains within it some vision for a preferred future, however implicit. Together, a diagnosis and its attendant proposition make up a theory of change. While it is increasingly common to imagine social change through the horizon of decolonization, there is also a range of analyses about what constitutes colonization, and propositions for how we should enact decolonization. Further, propositions for enacting decolonial futures do not always follow ‘logically’ from diagnoses of colonization. Particularly in a contemporary context within which epistemic authority is increasingly decentralized, diagnoses and propositions are often contradictory, and may be crafted out of convenience rather than coherent theoretical frameworks, political positions, or static values (Bauman, 2000).

In addition, we have noted that often there is a significant gap between one’s stated intentions and actual actions in efforts to decolonize. Recognizing the common gaps between what we say and what we do, the polarized nature of conversations about colonialism, and the risk of circularities involved in social change efforts, our strategy for engaging with different decolonial theories of change has been primarily pedagogical, rather than prescriptive in nature. That is, rather than normatively assert any particular diagnosis or proposition as the only viable or ethical approach to decolonization, we have sought to invite engagements with a range of possibilities, particularly using the methodology of social cartography, in which contrasting approaches to a common issue of concern are mapped, and their underlying political and philosophical investments are identified and unpacked in ways that make onto-epistemic choices and assumptions visible (Andreotti et al., 2016 Paulston, 2000; Suša & Andreotti, 2019).

In our experience, social cartographies can support people to clarify the conditions and particularities of their own context, and to sit with and learn from contradictions without seeking to immediately resolve them. Cartographies support the depth and rigor of intellectual processes by orienting these processes through critical generosity, attention to difference, and self-implication, and thus avoid simplistic or universal solutions to complex problems. At the same time, cartographies create space for the breadth and integrity of the affective and relational processes that are involved in facing the full scope of current challenges, and walking (and stumbling) together toward other possibilities, without determining the direction or outcome of change in advance of its doing.

Social cartographies can serve as a kind of “decolonial gesture,” which is, according to Marboeuf (2019), “conceived of in terms of discomfort, a discomfort that is not ephemeral, but long and shared” and thus, “We must learn to stay with problems, to stay with the trouble” (p.4). Indeed, cartographies invite those who engage them to “stay with the trouble” (Haraway, 2016), rather than turn away in search of immediate relief or resolution. Further, cartographies respect the different pace of each person’s learning, while also reminding people in dominant positions that they are accountable to those who are negatively affected by their learning and its pace, particularly given the magnitude and the urgency of the challenges that we face. The intention is ultimately to support people in making and taking responsibility for their own, critically-informed decisions about how to address pertinent challenges within their situated contexts.

All of this translates to interrelated pedagogical processes that can be used to support learners working with/through divergent positions on de/colonization, including:

· identifying different diagnoses of colonization, and the propositions for decolonization that follow from each diagnosis (i.e. different theories of change);

· tracing the assumptions, investments, and histories that underlie different decolonial theories of change in order to dislodge existing investments and interpretations, so as to ask what each enables and forecloses;

· thinking (self-)reflexively and systemically about our individual and collective relationships to these assumptions, investments, and histories in order to invite curiosity, reflexivity, openness, and the expansion of sensibilities;

· working with and through the edges, tensions, and contradictions between different theories of change, and acknowledging the partiality of each; and

· inviting (responsible) experimentation with decolonial openings and possibilities from a place of humility, generosity, healthy suspicion, and self-implication.

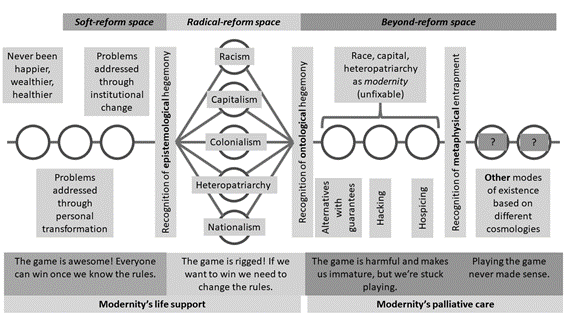

The house modernity built and theories of change

In order to illustrate the uses of social cartographies, we now review a version of one of our ‘root’ cartographies that we continuously revisit and revise in response to changing contexts and audiences (Andreotti et al., 2015). Here, we return to it with a renewed focus on how we might identify and interrupt patterns of decolonization that are oriented by consumptive desires premised on colonial habits of knowing, being, and relating, so that we might reorient decolonial efforts toward what we understand as a yearning for connection premised on ‘otherwise’ possibilities for (co)existence. This cartography is organized around different approaches to modernity, to illustrate how each space of identified mode of reform views the relationship between colonization and modernity differently – and thus, offers a different vision of decolonization.

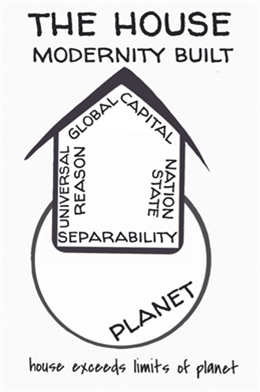

Before we review this map of different approaches to decolonization, we briefly review the significance of modernity to this work and our understanding of its constituent parts – which we describe using the metaphor of “the house modernity built” (Stein et al., 2017) (see Cartography 1). This metaphor synthesizes many critiques of modernity that have been mobilized in Indigenous, Black, decolonial, post-development, post-colonial studies, and (different genealogies of) psychoanalysis (e.g. Ahenakew, 2016; Ahmed, 2012; Alexander, 2005; Byrd, 2011; Coulthard, 2014; Cusicanqui, 2012; Escobar, 1992; Fanon, 2007; Gandhi, 2011; Harney & Moten, 2013; Kapoor, 2014; Lorde, 2007; Maldonado-Torres, 2007; Moten, 2013; Santos, 2007; Shiva, 1993; Silva, 2007; Simpson, 2017; Spivak, 1988; Taylor, 2013; Tuck, 2009; Tuck & Yang, 2012; Walia, 2013; Wynter, 2003; Zembylas, 2002). The metaphor is also deeply informed by our collaborations with Indigenous communities and other communities of struggle. The metaphor is living, meaning it is not static and it shifts depending on the contexts in which we present it; we invite participatory engagements with its continued reimagination.

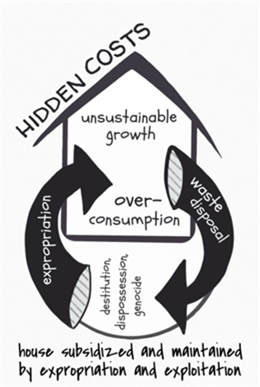

In this metaphor, the foundations of the house are built on a solid concrete that separates humans from the rest of nature, and creates degrees of hierarchical value that rank these ‘separate’ beings against each other according to their perceived utility (Mika, 2019; Silva, 2016). These fantasies of separation and hierarchy lay the onto-metaphysical groundwork for the rest of the house. The carrying walls of the house are represented, on one side, by tiles of Western humanist values and Enlightenment knowledge traditions, which promise consensus and universal relevance, and which are secured by denying the relevance of non-Western knowledges (Ahenakew, 2016; Santos, 2007; Smith, 2012). On the other side is the wall of nation-states, which promise security through the mechanisms of borders, rights, and national homogeneity, all of which are ultimately secured through processes of state sanctioned violence ‘at home’ and abroad (Byrd, 2011; Tuck & Yang, 2012). The roof of this house is made of tiles of global capitalism, layered over beams of continuous economic growth and consumption as a measure of progress and civilization (Coulthard, 2014; Silva, 2007). Thus, while the house modernity built offers shiny promises, these promises are subsidized by a colonial underside: the externalised and invisibilised costs of building and maintaining the house (see Cartography 2). This includes historical and on-going expropriation, land-theft, exploitation, destitution, preventable famines, incarceration, dispossession, epistemicides, ecocides, and genocides.

Cartographies 1 and 2: The house modernity built, and its hidden costs

One’s relationship to the house and investments (or lack thereof) in accessing its promises will depend in part on where one is situated in relation to it not only currently but also aspirationally (e.g. content being in the basement; monopolizing space on the top floors; seeking mobility from the bottom floor to the top; at the doors struggling to get in; outside of the house, but not seeking entry, etc.). We return to this metaphor of the house later, when we discuss what it might tell us about addressing contemporary challenges. First, though, we introduce another cartography that visualizes the implications of different relationships to modernity/coloniality, which give rise to three different approaches to social change: soft-, radical-, and beyond-reform.

Cartography 3: Different approaches to reform with regard to modernity/coloniality

Approaches to modernity/coloniality articulated from within the soft-reform space (or ‘soft-reform’ approaches to decolonization) focus on including marginalized populations into existing institutions. Colonization here is primarily diagnosed as a problem of exclusion from access to the gifts of modern societies: social mobility offered by capitalism; order and belonging offered by nation-states; universal reason offered by Western humanism and Enlightenment knowledge traditions; and unrestricted autonomy, authority, and possessive individualism offered by the separations of humans from the earth and from one another. The theory of change that orients soft-reform is one of methodological adjustments – the idea that the systems we inhabit are structurally sound, but need continuous improvement in practice in order to ensure their efficiency and effectiveness. While difference is not entirely elided, inclusion is conditional upon assent to a horizon of hope that is oriented by shared goals and coherence around continued support for existing social, political, and economic norms. The ideal here is to incorporate forms of “difference that make no difference”, as those who are included are meant to be smoothly absorbed into existing institutions. Alternative possibilities for organizing relationships and resources that challenge these norms are delegitimized or deemed illegible, and so the only possible proposition is to expand access to existing institutions.

In contrast to the soft-reform space, the radical reform-space identifies colonization as a product of exclusionary representation and inadequate redistribution – which then translates into questions about not only what we do in modern institutions (i.e. methodological concerns), but also how and why we do it (i.e. epistemological concerns). This diagnosis of colonization understands it as a by-product of modernity’s structures of domination. Thus, the proposition is that colonial harms can be redressed only by radically restructuring social relations. However, critiques from this space tend to disarticulate and prioritize one or sometimes two dimensions of colonialism (e.g. capitalist dispossession, racism, hetero-patriarchy, ableism, imposition of the liberal democratic nation-state form) rather than understanding their interconnections. The horizon of hope in this space is one of targeting the modern mechanisms that produce enduring inequities with the intention to fundamentally remake modernity itself. Thus, it is hoped that making more space for different knowledges, peoples, and experiences, and reallocating resources to support their presence, will lead to the transformation of an institution/system, rather than absorbing them into an institution/system that would otherwise be unchanged. Proposed strategies for decolonization in this space therefore include empowerment, amplifying/prioritizing the ‘voices’ of marginalized subjects (i.e. substantive representation that goes beyond mere tokenism), and resource redistribution.

The distinction between the radical- and beyond-reform spaces is the recognition that the representation of more ways of knowing and the redistribution of resources within existing institutions will not in themselves be adequate to shift the underlying onto-metaphysical infrastructures of the modern/colonial system. Colonialism is understood not merely as a matter of unequal resources or exclusionary ways of knowing, but rather as the condition of possibility for modern existence and institutions. Thus, colonialism is what makes modernity possible. Further, colonialism is inherently extractive and unsustainable; it cannot be reformed. From this perspective, adding epistemologies onto the same (modern) ontological foundation will always be a limited strategy for interrupting colonial harms and habits of being (Ahenakew, 2016; Ahenakew et al., 2014; Kuokkanen, 2008; Marboeuf, 2019). This does not mean that immediate reforms within modern, mainstream institutions – including redistribution, recognition, and representation – are unimportant, but that ultimately, these institutions cannot be redeemed, at least if the goal is to end ongoing colonization and enable different (decolonial) futures.

Theories of change rooted in the beyond-reform space are varied, but generally fall under one of three responses, each of which offers possibilities as well as limitations (and may be used in tandem): “walking out,” “hacking,” or “hospicing.” Those who attempt to “walk” out of the modern system are often seeking alternatives with guarantees. This might include, for example, efforts to develop or reclaim epistemologies and/or modes of social organization that have been actively repressed within modernity. While there is much to be learned from this work, when alternatives are engaged with a desire for guaranteed outcomes, they may still be rooted in at least some colonial desires (e.g. for certainty, progress, innocence), and may be romanticized to a point where their shortcomings and inevitable mistakes and contradictions are ignored (Amsler, 2019). As well, the ability to choose whether or not to ‘walk out’ should be understood in contrast to those who do not have the option, because they are not only structurally excluded from the system to begin with, but also their subjugation is what makes the system possible. In order to make this distinction, we describe those engaged in “high-intensity” versus “low-intensity” struggles. Neither of these struggles is any more or less important than the other – both are necessary – but one’s structural position in relation to these contrasting intensities should inform how one shows up to the larger project of decolonizing education.

Those who propose to “hack” modern institutions seek to redirect resources from within the system toward nurturing something else, whether that is educational efforts to identify the limits of those institutions, and/or to support other systems. This approach can be understood as a “one foot in, one foot out” approach, which requires that one “play the game” of the institution while trying to bend the rules toward other ends than “winning.” Much good work can be done through this approach, but it is sometimes difficult to know when one is playing the system or being played by it. Further, some operating in this space may position themselves outside of implication in the system in ways that centre individual resistance and fail to attend to structural complicity in harm.

The final beyond-reform proposition is what we have termed “hospicing,” which recognizes the inevitable end of modernity’s fundamentally unethical and unsustainable institutions, but sees the necessity of enabling a ‘good’ death through which important lessons are learned through the mistakes of the dying system, lessons that can then be applied as we witness and help to midwife the birth of something different.[2] This approach also requires that we hospice our own investments in modernity’s promises not as a reactive disidentificaiton with modernity and attempt to control the terms of its dissolution, which can paradoxically mirror colonial desires and reproduce many colonial patterns of consumption, but rather as self-implicated processes of facing up to the impacts of our own harmful desires and habits of being. At the interface between this death and birth is the imperative to walk steadily with the “eye of the storm” without knowing where it is headed: move either too fast or too slow and one gets swept up and up thrown around in the vortex of change. We elaborate further on this hospicing work later in the article.

Interrupting colonial circularities as the house of modernity falters

While it is important to understand the significant differences between these decolonial theories of change – that is, these diagnoses of colonization and propositions for decolonization – in the years that we have been working with this cartography we have found it increasingly vital to also attend to how these theories are actually mobilized and enacted.

In particular, we have noted that because of the colonial habits of being that many of us have been socialized into as subjects within modern systems and institutions, we need to attend to not only the intellectual dimensions of de/colonization, but also to its affective and relational dimensions. We find that no matter where one falls on the soft-radical-beyond reform spectrum, merely articulating or aligning with an intellectual critique of colonization does not immunize one from reproducing modern/colonial desires and habits of being. We have identified these recurring patterns in various educational contexts, as well as within ourselves. Indeed, we continue to observe our own difficulties in breaking these patterns, despite our intentions to do things differently.

It is therefore not (simply) a lack of information that leads to the reproduction of colonialism, including within efforts to decolonize, but also enduring affective investments in, and desires for, the continuation of its promises and pleasures. Thus, we suggest that any pedagogy of decolonization needs to address, with both critique and compassion, common CIRCULAR-ities that emerge in efforts to make change that nonetheless seek to retain or restore the following colonial entitlements and desires:

● [C]ontinuity of the existing system (e.g. “I want what was promised to me”)

● [I]nnocence from implication in harm (e.g. “Because I am against violent systems, that means I am no longer complicit in them”)

● [R]ecentering the self or majority group/nation/etc (e.g. “How will this change benefit me?”)

● [C]ertainty of fixed knowledge, predetermined outcomes, and guaranteed solutions (e.g. “I need to know exactly what is going to happen, when, and where”)

● [U]nrestricted autonomy, wherein interdependence and responsibility are optional (e.g. “I am not accountable to anyone but myself, unless I choose to be”)

● [L]eadership, whether intellectual, political, and/or moral (e.g. “Either I, or my designee, is uniquely suited to direct and determine the character of change”)

● [A]uthority to arbitrate justice (e.g. “I should be the one to determine who and what is valuable and deserving of which rights, privileges and punishments”)

● [R]ecognition of one’s righteousness and redemption (e.g. “But don’t you see that I’m one of the ‘good’ ones?”)

When these desires or perceived entitlements are not met, it can lead to feelings of frustration, hopelessness, and betrayal, which can in turn result in outward displays of various fragilities or even violence. When thinking educationally, if these desires are not identified, interrupted, and ‘composted’ that is, transformed into something different and more generative, then decolonization itself will either be outright resisted, or else be packaged into processes, experiences, or expressions that can be readily consumed in ways that appease these desires and may even have some short-term harm reduction benefits, but which will ultimately do little to interrupt underlying structures of harm.

In other words, while the intellectual work of tracing and connecting the social, political, and economic histories and contexts that shape the colonial present is a vital part of any decolonial effort, simply garnering more ‘information’ about colonial power relations does not necessarily disrupt dominant frames of knowing, being, hoping, and desiring that are themselves continuously (re)made through colonial relations. Despite (or perhaps, because of) our recognition of these circularities and short-circuits in ourselves and others, we remain committed to imagining other strategies for engaging with decolonial horizons of possibility, particularly in ways that keep these circularities visible without cynically suggesting their inevitability. Part of this enduring commitment stems from observations about the current state of “the house modernity built.”

According to some, the inherently unsustainable forms of political, economic, and ecological organization that characterize the house are starting to reach their limits (Bendell, 2018; Clover, 2016; Wainwright & Mann, 2013). Although life for those inside the house has always been subsidized through the expropriation and exploitation of those outside of the house, and in the house’s basement, the structure itself appears increasingly precarious and unstable: its cement foundations are cracking, the roof is leaking, and mold has developed in the basement and is working its way up the other floors (see Cartography 4). Even as the house falters, there are more people lining up outside its doors seeking access to the house as its outsized impact on the planet (from which it extracts resources, and onto which it disposes the resulting toxic waste) becomes more and more disruptive for those who are living outside of the house (whether by choice or forces of exclusion). Many of these same people have historically and involuntarily provided the labour and materials for the construction and maintenance of the house.

While many are in denial about the house’s shaky state, those who notice these cracks have a number of different reactions, which in turn can generally be mapped in relation to one’s approach to modernity, de/colonization, and related theories of change.

Cartography 4: Structural damage to the house modernity built

Those who have no critique of modernity/coloniality and feel their entitlements are at risk of being stripped away may simply seek to strengthen the fence around the house modernity built, or even to actively expel those who are perceived to be drawing on more resources than they contribute – generally, those denigrated by inherited racialized and nationalist narratives of inferiority/superiority and deservingness/undeservingness. People in this “no critique” position may even seek to intensify the crises of the house in an effort to create panic and exacerbate fears, and then instrumentalize these emotions to justify draconian policies. Needless to say, this position is uninterested in decolonization, and likely openly hostile to it. The result may be that with the increasingly evident unsustainability of the house will come an intensification of the existing colonial violences that have already targeted primarily Indigenous and Black populations (in the context of the Americas), and sustained the house for generations (Whyte, 2017).

For those in the soft-reform space, while some parts of the house may need to be patched up or even replaced, ultimately there is no perceived existential threat to its long-term persistence, nor any sense that there are viable alternatives to it.

Those in the radical-reform space may see the present as an opportunity to remodel the house entirely – expanding it to accommodate more people and using ‘green’ materials to replace old materials. However, they still tend to believe that the house has good scaffolding, and that it is not going anywhere any time soon.

Finally, those in a beyond-reform space diagnose the inherent sustainability of the house – and thus, the need to look beyond horizons of hope and change oriented by global capitalism, nation-states, universal reason, and separation. From this space, different propositions arise: the walk out approach seeks to replace the house using a blueprint for that nonetheless offers the same kind of security offered by the previous house – that is, a different kind of house, but still one with guarantees. The hacking and hospicing approaches might consider the need to experiment with other kinds of shelters, including by repurposing the material resources of the house, while also widening the emerging cracks in the house so as to invite people to glimpse these other possibilities, and engaging in immediate harm reduction measures for the most vulnerablized.

There are many potential circularities and overlaps that occur both within and between the soft-, radical-, and beyond-reform spaces. Thus, we have identified a need for pedagogical efforts that create learning opportunities through which people can not only encounter and engage in different intellectual critiques of colonialism, but also develop the intellectual, affective, and relational dispositions that can support them to admit the extent of the problem we face and work through their enduring colonial habits of being.

For example, many people – regardless of their preferred theory of change – are affectively invested in a linear, prescriptive, and predefined process of transformation. There is a demand for an immediate answer to the question, “If not this, then what?” Rarely are people interested in engaging with the uncertainties, difficulties, and messiness of decolonization, or in learning to work with and through their own complicities without seeking innocence, absolution, or a renewed sense of benevolence. In other words, even when we start to realize there is a problem with our inherited system, our critique often short-circuits (Hunt, 2018). Rather than commit to a long-term process of digesting and composting the fears, denials, and harmful habits that feed that system so that we can face its possible collapse, critique is funneled toward processes of consumption (of knowledge, relationships, experiences, and even critique itself) that appease those fears, entitlements, and desires. In this way, we fail to generate the fertilizer that might nurture different futures. Ultimately this avoids a deepening of responsibility to the well-being of a wider planetary metabolism, and thereby forecloses other possibilities for (co)existence.

While on the one hand the uncertainties of the present might lead some to be more tentatively open to alternative possibilities and thus willing to undertake the difficult and uncomfortable work of digesting and composting, the current lack of steady ground might also only reinforce the desire for guaranteed outcomes from those alternatives (and thus, desire to consume critique in ways that feed perceived colonial entitlements).

For instance, in soft-reform spaces, people desire to “check the box” of decolonization in ways that enable them to feel good and move on without giving anything up (Ahenakew & Naepi, 2016; Ahmed, 2012; Jefferess, 2012; Pidgeon, 2016; Tuck & Yang, 2012). In whitestream institutions like museums or universities, this often manifests in the formula “decolonization = business as usual + selective Indigenous content – guilt and risk of bad press” (Jimmy, Andreotti, & Stein, 2019). In radical-reform spaces, there is sometimes a problematic desire to position oneself as a heroic protagonist in ways that gloss over one’s complexity and structural complicity, erase the collective dimension of decolonial work, and falsely presume that there is a clearly defined path of change. And in beyond-reform spaces, the sense of urgency around the collapsing house can lead people to rush through the process of composting its old elements, tear the house down before it is ready to fall, and quickly erect something else, potentially leading to a failure to learn the necessary lessons that may only be repeated in the next form of shelter.

Distinguishing desiring from yearning

Our recognition of problematic patterns of response to instability in the house modernity built is tempered by our recognition that while growing disillusionment with the house creates important openings for transformation, some alternatives may turn out to be even more harmful than the house itself. In our pedagogical approach to decolonization, we therefore look for strategies that not only invite learners into spaces of curiosity, openness, and possibility, but also support them to cultivate the humility, stamina, and self-reflexivity that is needed to work through the challenges and contradictions of the present without circularly repeating old mistakes.

In particular, we work with processes of disillusionment. If what the house offered was illusions, then the loss of those illusions might not be such a bad thing, even if it might be painful. We support the development of discernment and critical literacies, including the aforementioned decolonial ‘radars’, that can enable us to step back from our immediate responses in order to more soberly trace the roots of our disillusionment, analyze the house itself, and consider different possible short-, medium-, and long-term responses. This includes trying to view ourselves and our responses through other peoples’ eyes. We also try to speak to what we have recognized as an underlying sense of yearning for something different in ways that bypass or disarm colonial desires.

Indeed, we have recognized that disillusionment with the house may be based not only on the growing sense that its promises are broken (or perhaps, were always false to begin with), but also in the sense that even when its promises are fulfilled, there is dissatisfaction with the violently enforced fantasies of separation that modernity presumes and (re)produces. Alexander (2005) argues that our visceral sense of entanglement with one another and everything has been mutilated through colonialism. Returning to the metaphor of the house modernity built, the foundation of separation between humans and ‘nature’, and humans and each other, has caused this sense of entanglement to be severed. While many have numbed themselves/ourselves to the resulting pain, Alexander states that the material and psychic dismemberment and fragmentation created by colonialism also produce “a yearning for wholeness, often expressed as a yearning to belong, a yearning that is both material and existential, both psychic and physical” (p. 281).

For Alexander, the source of this yearning is a “deep knowing that we are in fact interdependent – neither separate, nor autonomous” (p. 282). Although modern social organization denies this sense of “difference without separability” (Silva, 2016), offering instead either individualism or unhealthy enmeshments with conditional communities, the current era of uncertainty offers openings through which to invite people who are feeling disillusioned to consider what infrastructures and patterns of existence operationalize this sense of separability, so that we might trace its violent and unsustainable impacts, and encounter the possibility that we can organize and orient our existence otherwise, that indeed ‘otherwise’ possibilities already exist. This work is all the more urgent given the fact that many responses to current challenges seek even more vigorously to fortify the illusion of separation, so as to protect perceived entitlements and desires.

Rather than imparting knowledge and information related to what learners should or should not desire, we seek to draw their attention to how desires have generally been allocated within modernity through intellectual, affective, and material economies of value. The pedagogical intention is to people learners to consider: How has our education trapped us in conceptualizations of (and relationships with) language, knowledge, agency, autonomy, identity, criticality, art, sexuality, earth, time, space, and self…that shape and restrict our horizons of hope and possibility, and what we consider to be possible/intelligible? What restricts what is possible for us to sense, understand, articulate, want, and imagine? As noted in our discussion of social cartographies, this pedagogical work is not politically prescriptive – it does not articulate and advocate a single theory of change (neither diagnosis nor proposition) – but rather invites engagements with multiple theories premised on the depth and rigor of intellectual engagement, and breadth and integrity of the learning process itself, including in its non-intellectual (especially relational and affective) dimensions. We invite learners to distinguish between the (often-harmful) desires that are allocated and mobilized by modernity/coloniality and the yearning that Alexander talks about, but we also cannot coerce learners to “rearrange their desires” (Spivak, 2004) toward a particular direction or outcome. We also recognize the importance of responsible experimentation with other possibilities for existence outside the house modernity built. We discuss this further in the following section.

Being taught by possibilities beyond the house

The Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures collective works alongside several Indigenous communities organized through the “In Earth’s CARE” network. The network is centered on members’ common interest in experiential, land-based learning. Together, we ask the following questions: How can we learn to tap into other possibilities for (co)existence that are viable but unintelligible or seemingly impossible within dominant paradigms? What educational processes can override modern socialized habits and embodied responses (fears, anxieties, self-interest, narratives, ego, narcissistic tendencies, wounds, etc.), to activate a sense of entanglement, responsibility, humility, and generosity (that are not conditional on calculations of self-interest), and open up possibilities/worlds that are viable, but unimaginable or inarticulable within our current frames of reference?

Communities in the In Earth’s CARE network generally approach the house modernity built from a beyond-reform perspective, and thus set their horizons of hope beyond global capitalism, nation-states, universal Western reason/values, and separability. These communities have much to teach about survival beyond the futurity of the house. At the same time, we do not assume that everyone is entitled to those teachings, nor do we believe that any community has universal answers. We are also wary of efforts to instrumentalize these learnings in order to ‘save’ the house. This is why, as noted earlier, we do not approach these communities and their practices as universal models to emulate. Instead, we understand them as examples of alternatives that both signal the limits of the house, and remind those still living inside of it that other ways of living are possible.

In this work, we have sought to develop an “alternative way of engaging with alternatives” (Santos, 2007). We do this by engaging examples of alternatives with reverence for their gifts, but without romanticization, and without projecting our desires onto them. We also attend to the challenges, tensions, and potential violences that are enacted when relating across different sensibilities as well as relating across communities with uneven historical and structural power (Jimmy, Andreotti, & Stein, 2019). In particular, in these engagements we recognize in ourselves and others the risks of: homogenizing diverse communities in ways that belie their complexities and internal power relations; idealizing ‘alternative’ ways of knowing and being, and the communities that practice them, which is the mirror opposite of pathologizing them; enacting escapist fantasies that allow us to immerse ourselves in other kinds of shelter in order to avoid the necessary work of hospicing the house we have inherited; and distorting and/or instrumentalizing alternatives to feed our own consumptive colonial desires (Ahenakew, 2016;Amsler, 2019; Spivak, 1988). Thus, we ask: How can we encounter and be taught by different systems of knowing, being and desiring, and by practical struggles and attempts to create/regenerate alternatives to the house modernity built, while remaining aware of their gifts, limitations, and contradictions, as well as accountable for our own potential (mis)interpretations, projections, appropriations, and tendencies toward consumption?

While as part of this research we conduct collaborative case studies of different initiatives and organizations, per our discussions with each other and with our collaborators, and in consideration of what will be most useful for the learning of our students and others who are struggling to make sense of a crumbling house, the primary research “outcomes” from this work are not narrative reports of empirical findings. We find that offering these descriptions or representations tends to feed desires to consume (and generally, romanticize and/or pathologize) difference, and to relate to others by knowing about them in ways that do not actually interrupt harmful projections, power relations, or dominant frames of reference. That is, it would not necessarily prompt people to grapple with the fact that different ways of knowing and being might be unintelligible to us from within our inherited frames – and that we might be reproducing further harm by assuming that they are (Ahenakew, 2016; Marboeuf & Yakoub, 2019; Spivak, 1988).

Offering descriptive accounts can also feed the colonial desire for an assurance that there are viable, pre-made alternatives that can replace a dying system, rather than invite people to turn toward the storm ahead and become comfortable with the unknown and the unknowable. Because descriptive accounts do not necessarily prompt a “rearrangement of desires,” we have instead created pedagogical frameworks and artistic experiments informed by our own difficult and messy learning at the interface between different communities and experiences – including the ones presented in this piece.

These frameworks are partial and provisional. They will not work universally, and certainly will not work in the same way for every person, community, or country. Thus, we encourage people who are interested to relate to the frameworks not as something they identify or disidentify with, but rather as something that helps start and hold difficult conversation with and between different contexts and perspectives. However, this more emergent approach to learning and doing frustrates those looking to be inspired or convinced by a totalizing narrative that offers predetermined, guaranteed solutions.

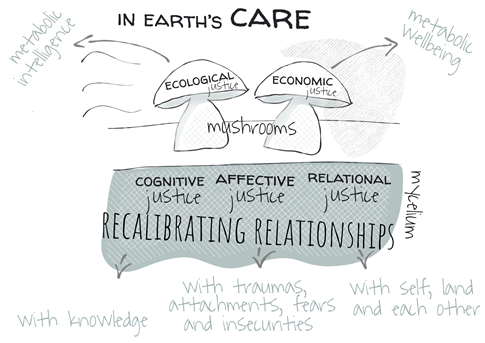

One of the pedagogical frameworks that we have collaboratively developed is the In Earth’s CARE Global Justice and Well-Being framework, which integrates Ecological (“Earth”), Cognitive, Affective, Relational and Economic dimensions of transformation (see Cartography 5). As we were developing the framework, Carmen Ramos of the Nahuatl organization Tlalij, which is part of the In Earth’s CARE network, emphasized the need to make visible the often invisibilized labour of the Earth in supporting all life, and to consider our particular, situated responsibilities to it and to each other as entangled beings within its larger metabolism. In particular, she clarified that it is not (only) that we seek to care for the Earth, but that we are always already in Earth’s care. In doing so, Ramos also prompted us to consider that, while there is a tendency to prescribe a political normativity and let that dictate our relationships, in fact it is the quality of our relationships (to all beings) that determines the political possibilities that are viable in any particular context. From this perspective, rather than spend our time perfecting an articulation of our political stance using the same limited set of cognitive, affective and relational configurations, we would need to start by expanding and nurturing different kinds of configurations in order to open up the possibility for a politics that could uphold the integrity of our relationships and the responsibilities that follow from them. Needless to say, this is a very different approach to politics than is generally supported by the house, which is based on an onto-metaphysics in which our existence (being) is determined by our thinking, and thus, it is believed that our convictions dictate our behavior.

In the In Earth’s CARE framework, we use the metaphor of mushrooms to represent the ecological and (political) economic dimensions of transformation; underneath them, underground, is the mycelium of the cognitive, affective, and relational dimensions, which feed the mushrooms and enable them to live – and when the time is right, to die. Thus, in order to support the growth of other kinds of mushrooms, we will need to start by composting old mycelium so that they can serve as fertilizer for new growth.

Cartography 5: In Earth’s CARE Global Justice and Well-Being Framework

Uneasy conclusions and questions for further conversation

In this article, we have discussed some of the potential circularities, short-circuits, and contradictions that emerge in efforts to enact decolonization, including those that reproduce colonial habits of being rooted in the consumptive desires and entitlements cultivated by the house modernity built. We have also suggested that none of the many existing and possible decolonial theories of change are immune to these risks, including our own. In practice, efforts to enact change are shaped not only by conceptual analyses but also by the individual and collective affective investments that are cultivated by the house. In this sense, they are somewhat unavoidable, which means that there is a need for our pedagogies to anticipate colonial circularities in ways that problematize them but also invite people to work through (rather than deny, transcend, or repress) them. This work can be summarized as a pedagogical commitment to invite deepened engagement with the complexities and contradictions of different theories of change related to patterns of knowing, being, relating, and desiring that are fed by the house, without advocating any particular theory as “the answer” or model for what we should do.

We also reviewed some of our own efforts to engage with and be taught by possibilities outside of the house. This work has taught us that, as educators, we can ask people to engage with intellectual rigor, but we can only offer an open invitation to engage with other possibilities for existence if learners feel called to do so. This is because rather than a question of will or intellect, the latter work requires a certain amount of existential surrender, that is learning to: disarm; decenter; and disinvest from the promises of the house; and practice knowing, being, and relating ‘otherwise’, with the knowledge that it will be uncomfortable and mistakes will be made. Rather than offering maps, blueprints, or manifestos, this work supports people to develop dispositions and radars for remaining attentive to the potential circularities involved in the face messy, ongoing work of decolonization, and remaining oriented toward decolonial horizons. In other words, this work supports people to ‘stay with the trouble’ of decolonization.

Even if the house modernity built is ultimately going to collapse, in the context of its crumbling we are also conscious of the imperative to mitigate the vulnerability of those already exposed to the most violence – and who are most likely to be harmed (yet again) in the wake of its potential collapse. To conclude this article, we propose the following intellectual questions that can support the work of digging deeper into our current context:

1. How does what happened in the past relate to and inform what is happening in the present? Specifically, what lessons have we yet to learn from the past that may be useful for making sense of the challenges we face in the present?

2. How does what has happened in the past differ from what is happening in the present? Specifically, how might we need to rethink our inherited strategies for both conceptual analysis (diagnosis) and practical response (propositions)?

3. What might we learn by suspending our desire for universal or prescriptive solutions and by instead attending soberly to what is currently working, and what is not, and based on this analysis, determine what different responses are needed in the short-, medium-, and long-term? How can we do this work of responding while maintaining an ongoing commitment to continuously assess these plans rather than remain attached to an orthodoxy that is not working?

The above questions primarily target the intellectual dimension of addressing the challenges of a crumbling house, but this work will be insufficient if it is not paired with sustained efforts to rewire our affective and relational habits as well. Thus, we also ask: How can we mobilize “alternative ways to engage with alternatives”, that is, how can we move together differently toward a future that is undefined, without arrogance, self-righteousness, dogmatism, and perfectionism? As a provisional answer to this question, we offer the following orienting practices and dispositions for relating wider:

· Disinvestment (from the house) without aversion to it that is based in reactive and redemptive disidentification with it;

· Reverence (for the gifts of alternatives) without idealization or romanticization;

· Experimentation (as necessary for learning) without attachment to ‘successful’ outcomes;

· Responsibility (for all beings) without paternalism, or projecting our desires and entitlements onto others as if they were universal; and,

· Self-implication (in harm) without seeking immunity, absolution, or escapism.

References

Ahenakew, C. (2016). Grafting Indigenous ways of knowing onto non-Indigenous ways of being: The (underestimated) challenges of a decolonial imagination. International Review of Qualitative Research, 9(3), 323-340.

Ahenakew, C., Andreotti, V. D. O., Cooper, G., & Hireme, H. (2014). Beyond epistemic provincialism: De-provincializing Indigenous resistance. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 10(3), 216-231.

Ahenakew, C., & Naepi, S. (2015). The difficult task of turning walls into tables. In A. Macfarlane (Ed.), Sociocultural realities: Exploring new horizons, (pp. 181-194). Canterbury University Press.

Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Duke University Press.

Alexander, M. J. (2005). Pedagogies of crossing: Meditations on feminism, sexual politics, memory, and the sacred. Duke University Press.

Amsler, S. (2019). Gesturing towards radical futurity in education for alternative futures. Sustainability Science, 14(4), 925-930.

Andreotti, V. (2016). Multi-layered selves: Colonialism, decolonization and counter-intuitive learning spaces. Arts Everywhere – Musagetes. http://artseverywhere.ca/2016/10/12/multi-layered-selves/

Andreotti, V. D. O., Stein, S., Ahenakew, C., & Hunt, D. (2015). Mapping interpretations of decolonization in the context of higher education. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 4(1).

Andreotti, V. D. O, Stein, S., Pashby, K., & Nicolson, M. (2016). Social cartographies as performative devices in research on higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(1), 84-99.

Andreotti, V., Stein, S., Sutherland, A., Pashby, K., Suša, R., & Amsler, S. (2018). Mobilising different conversations about global justice in education: toward alternative futures in uncertain times. Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, 26, 9-41.

Bauman, Z. (2000). Education under, for, and despite postmodernity. In A. Brown, & M. Schemmann (Eds.), Language, mobility, identity: Contemporary issues for adult education in Europe (27-43). Lit Verlag.

Bendell, J. (2018). Deep adaptation: a map for navigating climate tragedy. https://mahb.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/deepadaptation.pdf

Byrd, J. A. (2011). The transit of empire: Indigenous critiques of colonialism. University of Minnesota Press.

Clover, J. (2016). Riot. Strike. Riot: The new era of uprisings. Verso Books.

Coulthard, G. (2014). Red skin, white masks: Rejecting the colonial politics of recognition. University of Minnesota Press.

Cusicanqui, S. R. (2012). Ch'ixinakax utxiwa: A Reflection on the Practices and Discourses of Decolonization. South Atlantic Quarterly, 111(1), 95-109.

Eriksen, K.G. (2018a). Education for sustainable development and narratives of Nordic exceptionalism: The contributions of decolonialism. Nordidactica: Journal of Humanities and Social Science Education, (2018: 4), 21-42.

Eriksen, K. G. (2018b). Teaching about the Other in primary level social studies: The Sami in Norwegian textbooks. JSSE-Journal of Social Science Education, 57-67.

Escobar, A. (1992). Reflections on ‘development’: grassroots approaches and alternative politics in the Third World. Futures, 24(5), 411-436.

Fanon, F. (2007). The wretched of the earth. Grove.

Gandhi, L. (2011). The pauper's gift: Postcolonial theory and the new democratic dispensation. Public Culture, 23(1), 27-38.

Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

Harney, S., & Moten, F. (2013). The undercommons: Fugitive planning and black study.

Höglund, J., & Burnett, L. A. (2019). Introduction: Nordic colonialisms and Scandinavian Studies. Scandinavian Studies, 91(1-2), 1-12.

Hunt, D. (2018). “In search of our better selves”: Totem Transfer narratives and Indigenous futurities. American Indian Culture and Research Journal, 42(1), 71-90.

Jefferess, D. (2012). The “Me to We” social enterprise: Global education as lifestyle brand. Critical Literacy: Theories and Practices, 6(1), 18-30.

Jimmy, E., Andreotti, V., & Stein, S. (2019). Towards braiding. Musagetes Foundation.

Kapoor, I. (2014). Psychoanalysis and development: Contributions, examples, limits. Third World Quarterly, 35(7), 1120-1143.

Kuokkanen, R. (2008). What is hospitality in the academy? Epistemic ignorance and the (im) possible gift. The Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 30(1), 60-82.

Lorde, A. (2007). The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. Sister outsider: Essays and speeches (pp. 110-114). Crossing Press.

Maldonado-Torres, N. (2007). On the coloniality of being: Contributions to the development of a concept. Cultural studies, 21(2-3), 240-270.

Marboeuf, O., & Yakoub, J. B. (2019). Decolonial variations: A conversation between Olivier Marboeuf and Joachim Ben Yakoub. https://oliviermarboeuf.files.wordpress.com/2019/05/variations_decoloniales_eng_def.pdf

Mika, C. (2019). Confronted by Indigenous metaphysics in the academy: Educating against the Tide. Beijing International Review of Education, 1(1), 109-122.

Mitchell, N. (2015). (Critical ethnic studies) intellectual. Critical Ethnic Studies, 1(1), 86-94.

Moten, F. (2013). The Subprime and the beautiful. African Identities, 11(2), 237-245.

Naepi, S., Stein, S., Ahenakew, C., & Andreotti, V. D. O. (2017). A cartography of higher education: Attempts at inclusion and insights from Pasifika scholarship in Aotearoa New Zealand. In Global teaching (pp. 81-99). Palgrave Macmillan.

Paulston, R. G. (2000). Imagining comparative education: Past, present, future. Compare, 30(3), 353-367.

Pidgeon, M. (2016). More than a checklist: Meaningful Indigenous inclusion in higher education. Social inclusion, 4(1), 77-91.

Santos, B. S. (2007). Beyond abyssal thinking: From global lines to ecologies of knowledges. Review (Fernand Braudel Center), 45-89.

Shiva, V. (1993). Monocultures of the mind: Perspectives on biodiversity and biotechnology. Palgrave Macmillan.

Silva, D.F.D. (2007). Toward a global idea of race (Vol. 27). University of Minnesota Press.

Silva, D.F.D. (2016). On difference without separability. https://issuu.com/amilcarpacker/docs/denise_ferreira_da_silva

Simpson, L. B. (2017). As we have always done: Indigenous freedom through radical resistance: University of Minnesota Press.

Spivak, G. (1988). Can the subaltern speak? In C. Nelson & L. Grossberg (eds.), Marxism and the interpretation of culture (pp. 271-313). University of Illinois Press.

Spivak, G. C. (2004). Righting wrongs. The South Atlantic Quarterly, 103(2), 523-581.

Stein, S. (2017). A colonial history of the higher education present: Rethinking land-grant institutions through processes of accumulation and relations of conquest. Critical Studies in Education, 1-17.

Stein, S. (2019). Beyond higher education as we know it: Gesturing towards decolonial horizons of possibility. Studies in Philosophy and Education.

Stein, S. (2020). ‘Truth before reconciliation’: the difficulties of transforming higher education in settler colonial contexts. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(1), 156-170.

Stein, S., & Andreotti, V.D.O. (2016). Decolonization and higher education. In Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory (pp. 1-6). Springer.

Stein, S., & Andreotti, V.D.O (2017). Higher education and the modern/colonial global imaginary. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, 17(3), 173-181.

Stein, S., Hunt, D., Suša, R., & Andreotti, V. (2017). The educational challenge of unraveling the fantasies of ontological security. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 11(2), 69-79.

Suša, R., & de Oliveira Andreotti, V. (2019). Social cartography in educational research. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education.

Taylor, L. K. (2013). Against the tide: Working with and against the affective flows of resistance in social and global justice learning. Critical Literacy: Theories & Practices, 7(2).

Tuck, E. (2009). Suspending damage: A letter to communities. Harvard Educational Review, 79(3), 409-428.

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education &Society, 1(1),1-40.

Wainwright, J., & Mann, G. (2013). Climate leviathan. Antipode, 45(1), 1-22.

Walia, H. (2013). Undoing border imperialism. AK Press.

Whyte, K. (2017). Indigenous climate change studies: Indigenizing futures, decolonizing the Anthropocene. English Language Notes, 55(1), 153-162.

Wynter, S. (2003). Unsettling the coloniality of being/power/truth/freedom: Towards the human, after man, its overrepresentation—An argument. CR: The New Centennial Review, 3(3), 257-337.

Zembylas, M. (2002). "Structures of feeling" in curriculum and teaching: Theorizing the emotional rules. Educational Theory, 52(2), 187-208.