NJCIE 2020, Vol. 4(3-4), 139–156 http://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.3746

Exploring Headway Pedagogies in Teacher Education Through Collaborative Action Research into Processes of Learning: Experiences from Eritrea

Khalid Mohammed Idris[1]

Educator, Asmara College of Education

Samson Eskender

Educator, Ministry of Education

Amanuel Yosief

Asmara College of Education

Berhane Demoz

Educator, Ministry of Education

Kiflay Andemicael

Regional Education Head, Ministry of Education

Abstract

Engaging prospective teachers in a collaborative inquiry into their own processes of learning was the driving intention of the action research course which was part of a teacher education program at a college of education in Eritrea in the academic year of 2018/2019. The course was collaboratively designed and developed by the authors who were closely and regularly working as a passionate learning community of educators to enact change in their own practices for the past eight years. Building on the emerging literature on developing a pedagogy of teacher education through self-study, we engaged in an intentional collaborative self-study into our own practices of collaboratively facilitating a course on inquiry among a senior class of student-teachers (n=27). This article aims to articulate pedagogic experiences of committed collaborative learning in facilitating a cycle of action research among a group of student-teachers. Qualitative methods, including transcripts of practice-based series of discussions among the authors and course artifacts, were used in identifying, describing, and analyzing our pedagogic experiences that resulted in reframing our roles as educators. Our findings show a trajectory of pedagogic experiences that reframed our roles from facilitators of prescribed contents of inquiry to co-constructors of learning experiences, and from supervisory roles to enablers of collaborating student-teacher teams in shaping the outcomes of their action research projects. Implications for a pedagogy of action research and teacher education practices are discussed along with possible areas for further research.

Keywords: pedagogy of teacher education, teacher-educators, action research, self-study, Eritrea

Introduction

Engaging pedagogical practices have been advocated in teacher education contexts mainly to model pedagogical practices espoused in K-12 schools as the learner-centered education (Mtika & Gates, 2010; Vavrus et al., 2011). In the sub-Saharan context, studies show that teacher education learning contexts need to be transformed by foregrounding realities and practices of K-12 schools in their programs and develop practices that better prepare student-teachers to facilitate quality learning (Akyeampong et al., 2013). Yet, there is a significant gap in the literature showing processes of active learning in teacher education settings in general and the role of teacher-educators in leading such a process in particular (Westbrook et al., 2013).

The professional development of teacher-educators is directly linked to the quality of initiating and leading engaging and worthwhile learning in teacher education settings (Loughran, 2014). Despite acknowledgments of teacher-educators for the need of systematic and structured preparation for their work (Goodwin et al., 2014), they are often left on their ‘own’ in navigating through their complicated role of preparing student-teachers particularly concerning modeling exemplary pedagogies in their courses. Beyond lecturing course contents, teacher-educators are challenged in developing and modeling contextually relevant pedagogies because the “way [they] teach IS the message” (Russell, 1997 as cited in Korthagen, 2016, p. 331).

This article attempts to identify, describe and analyze pedagogical experiences gained by the authors while they were engaged in intentionally developing and managing a course on inquiry among a senior group of student-teachers in a teacher education setting. Intentionally positioning teacher education settings as sites of inquiry (Loughran, 2013, as cited in Fletcher et al., 2016, p. 306) employing self-study methodology (Korthagen, 2016; Loughran, 2014) is increasingly being seen as vital practices in making better sense in preparing student-teachers and developing identities as educators of teachers.

Self-study as a genre of practitioner research is proving to have a critical role in appreciating and developing pedagogy in teacher education settings (Cuenca, 2010; Mena & Russel, 2017). As a passionate community of educators motivated to understand and improve our practices and encouraged by those intellectual developments in teacher education we set out to intentionally study our practices collaboratively. We have been collaborating in developing an action research course in two teacher education settings in Eritrea since 2014. We have focused on the course for its strategic implications in teacher learning in overcoming professional isolation, developing self-regulative practices in learning and teaching, and generation of school scholarships in guiding practices (Sagor, 1992). The theoretical and practical underpinning of action research and self-study research are very similar (LaBoskey, 2004, p. 838). Self-study research focuses more on improving teacher-educators’ practices by reframing their roles (Klein & Fitzgerald, 2018) while facilitating strategic courses, as action research, in teacher learning and development.

The action research course was designed to support a group of student-teachers (n=27) so that they experience critical competencies needed in school work practices. Aligning with the methodological principles of self-study, we opened up our intentions and practices to critical scrutiny (Klein & Fitzgerald, 2018) employing a ‘layered’ approach of critical friendship (Fletcher et al., 2016). We engaged in a series of practice-based and focused discussions that were informed and enriched by formal and informal feedback of the student-teachers shared through diverse means. Our findings show a trajectory of pedagogic experiences that reframed our roles from facilitators of prescribed contents of inquiry to co-constructors of learning experiences, and from supervisory roles to enablers of collaborating student-teacher teams in shaping the outcomes of their action research projects. We argue those experiences have relevance for developing a pedagogy of action research and teacher education practices in shaping K-12 school teaching practices.

In the next section, we position the article in self-study of teacher education practices literature in underlining the agentive role of teacher-educators in developing worthwhile scholarship in the pedagogy of teacher education.

Self-study Research and Pedagogy of Teacher Education

Self-study research has become an established methodology in teacher education as a sound and appropriate mechanism for the professional development of teacher-educators and mainly for developing relevant pedagogy in teacher education contexts (Korthagen, 2016; Ping et al., 2018). Teacher-educators need to learn to develop inquisitive and critical stance about their practices in learning to improve and model their pedagogical intentions but also to ‘unlearn’ practices and beliefs that could be antithetical to espoused pedagogical ideals and intentions (Cochran-Smith, 2003). However, studies point out that teacher education programs and teacher-education practices significantly fall short of modeling learning and teaching practices expected of student-teachers in K-12 schools (Akyeampong et al., 2013; Mtika & Gates, 2010). Self-study research in teacher education practices expose the centrality and deeper notions of pedagogy that is often overlooked (Cuenca, 2010) or disregarded altogether as university or college-based educators assume and routinize their roles as ‘lecturers’ of courses. This trend has largely exacerbated the theory-practice conundrum in teacher education (Korthagen, 2016) making teacher education establishments as part of the problem in pedagogical changes reinforcing an entrenched culture of rote learning and excessive exam orientation in K-12 school settings (Idris et al., 2017).

Those learning realities were typical in our teacher education and school settings. We were particularly encouraged by the epistemological orientations of self-study research in improving our learning context and seeing the impact of our intentional practices on student-teachers’ learning and our professional development (Bullough & Pinnegar, 2001, as cited in Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2004). Grounded in social constructivist theory (LaBoskey, 2004), self-study creates engaging pedagogic spaces for teacher-educators in making sense of their practice, meaningfully support their learners, and develop as scholars of teacher education practices (Ping et al., 2018). Improvement aimed designs or interventions, closer and collaborative studies of initiatives with the emphasis of selves in practice (Fletcher et al., 2016) create opportunities in gaining pedagogical insights from analyzing teacher education practices (Mena & Russel, 2017).

Self-study research necessarily constitutes collaborative practices (Bodone et al., 2004). Accordingly, teacher-educators actively engage in creating and sustaining a learning space in a community “where [they] inquire together into how to improve their practice in areas of importance to them, and then implement what they learned to make it happen” (Hargreaves & Fullan 2012, p. 127). The authors of this article have been actively engaged in improving educational practices in Eritrea in general and teacher education practices in particular over the past eight years and the community has been a source of inspiration in generating contextually relevant initiatives through processes of “rethinking and reframing practices” (Peercy & Troyan 2017, p. 29). The personal and professional relationship sustained over some time is an important contextual feature of critical friendship in self-study research (Schuck & Russell, 2005). Intentionally developed and sustained collaborative milieu is powerful in developing and enacting pedagogical innovations (Fletcher et al., 2016). As critical friends get opportunities to share perspectives from the practice they tend to get immediate feedback, stimulation, and critique that increasingly leads to reflexivity (Hamilton et al., 2008, p. 24).

Before exploring the context of our self-study further, we briefly review key issues of introducing action research in teacher education programs which was the basis for our collaborative self-study.

Action Research in Teacher Education Programs

Action research is advocated in teacher education programs to provide foundations for understanding prospective roles of student-teachers as reflective practitioners (Pellerin & Paukner, 2015) and influence changes in school teaching practices by developing rigorous requirements while carrying out action research projects (Spencer & Molina, 2018). Vaughan and Burnaford’s (2016) review of action research in graduate teacher education programs shows a trend of designing action research to be a cross-cutting course emphasizing its collaborative dimensions among student-teachers, faculty, and K-12 school communities. Furthermore, emerging studies are recognizing the importance of engaging student-teachers into researching aspects of their own learning and teaching practices (Wrench & Paige, 2019). “Self-reflective inquiry undertaken by teachers is central to aims for improving pedagogical practices, understanding the justice implications of these practices and the classrooms in which they are enacted” (Wrench & Paige, 2019, p. 2). Yet, how teacher-educators learn to enact those strategic intentions of action research need adequate and deeper exploration.

Context

The college of education (CoE) where the self-study was based (academic year of 2018/2019) was part of the then Eritrea Institute of Technology about 25 km away from the capital city, Asmara. After the restructuring of higher education in the country in 2018, the college has been relocated to Asmara and established a new one-year postgraduate diploma program in education. Hence, the student-teachers (n=27) who were taking the action research course were among the last batches of the program that was being phased out. The CoE had several challenges in its practices and programs in preparing teachers. Student-teachers with the least motivation to teach and lowest academic performance were being admitted (Idris et al., 2017). The learning and teaching process was generally lecture dominated, confining student-teachers to limited sources of knowledge (e.g. compiled handouts) and exam-oriented and dominated assessment system. The teacher education program was offered in a fragmented manner (Idris et al., 2017) with the subject-specific courses (mainly the natural sciences) being offered by a college of science, along with foundational, methodology, and research courses offered at the CoE. Furthermore, there were minimal efforts in linking the courses studied at the colleges with the school teaching practice which was done for a very short period, i.e., four weeks.

We were keen to emphasize the collaborative dimension of action research (Vaughan & Burnaford, 2016) because we believe that developing collaborative commitments among student-teachers would facilitate in maturing professional identities in basic school work practices by developing collaborative research competencies. Throughout our experience in facilitating the course, we have been learning invaluable lessons for developing focused course purpose, process, and content. Beyond the traditional course outline usually practiced at the CoE, which mainly sketches course contents, we have set out to develop a detailed course design that reflected and represented our intentions.

The action research course was offered to diploma and degree program student-teachers with the former being prepared to teach in middle schools and the latter in secondary schools. The first author, teacher-educator at the CoE, was responsible for leading the course during the academic year of 2018/2019, Semester I for 27 senior student-teachers in a degree program. The second author volunteered to co-teach the course though he was not an employee at the CoE. Authors 3 (Amanuel Yosief – Aman[2]), 4 (Berhane Demoz – Berhin), and 5 (Kiflay Andemicael) have closely followed the course through the series of focused discussions which were done twice a week (n=34 sessions) throughout the course and they have conducted visits to the classroom as guest educators during the first day of the course and the final sharing session.

The course was designed to provide the student-teachers hands-on opportunities to go through a cycle of collaborative action research (Sagor, 1992, emphasis added). The critical inquiry stages included problem development, data collection, analysis, developing intervention plans, interventions, developing findings, and sharing (Table 1). The focus of the collaborative inquiries were student-teachers’ own and ongoing processes of learning at the CoE and college of science where major subjects (biology courses) were offered. During the academic semester (sixteen weeks), we planned to engage in profound self-study in collaboratively facilitating the course by engaging in a series of focused discussions in reflecting on the process and learning to adapt fitting methods in guiding and supporting the student-teachers.

Based on this background, the following question guides the structuring and development of this article: What pedagogical experiences influenced our roles as educators in collaboratively facilitating an action research course among a group of student-teachers?

Methodology

The distinguishing feature of self-study methodology from action research is “its methodology rather than the methods used […] it would make the experience of teacher educators a resource for research” (Feldman et al., 2004, p. 943). Accordingly, the collaboratively developed course design was our research design (LaBoskey, 2004, p. 839) in our intentional practice of detailing and explicating our pedagogical moves in supporting student-teachers’ engagements in a collaborative action research cycle. LaBoskey (2004) sets guiding characteristics of self-study research as being self-focused and initiated, improvement aimed, being interactive, methodologically eclectic, and “exemplar-based validation to establish trustworthiness” (p. 853). The collaborative self-study was initiated by the authors in impacting significant changes in the learning of prospective teachers by designing and developing a strategic course.

The first two authors, Khalid Mohammed Idris and Samson Eskender (Sami) facilitated the course for sixteen weeks. Aman and Berhin have engaged in co-facilitating a similar course at another teacher education setting in Eritrea, the former Asmara Community College of Education (ACCE), in a previous academic year. Their experiences have inspired and informed the design and development of the action research course at the CoE. Hence, Aman, Berhin, along with Kiflay served as critical friends throughout our series of focused discussions. Critical friendship plays a vital role in encouraging and nurturing self-study practices among teacher-educators (Schuck & Russell, 2005). Crucially, “critical friends are essential in providing support for and critical feedback to the inquiry process, whether that be through how teachers establish tasks, run their classrooms, or engage students in active methods of learning” (Ritter et al., 2019, p. 151).

Methods

Qualitative methods mainly the practice-based series of discussions (n=34 sessions), were used in collaboratively learning to develop the course. We met to discuss twice a week on Tuesdays and Fridays after every facilitation session at the college throughout the semester. The series of focused discussions were intentional and focused. They were intentional because they were meant to make a better sense of unfolding experiences of course facilitation and develop practice-based strategies to improve the course. They were focused because they were based on organized and process-based briefings of the first two authors framed by the course design. A layered approach to critical friendship was adapted during the series of discussions as the first two authors engaged in closely interacting to develop the course regularly and Aman, Berhin, and Kiflay acting as “meta critical friends” (Fletcher et al., 2016, p. 306) in supporting and critiquing pedagogical initiatives of the first two authors based on their expertise and previous experience in facilitating a similar course.

In addition to the intentional and grounded discussions, we employed artifacts in supporting student-teachers’ learning in capturing nuances of course facilitation and making sense of our unfolding experiences. The artifacts included individual diaries of the first two authors, documents including edited action research reports of student-teachers from a previous cohort at the former ACCE, and a reflective report of Aman who was the lead educator of the action research course at the ACCE. Sami was co-teaching in class with Khalid for seven weeks. Afterward, he was mainly following student-teachers through a virtual platform, i.e., the WhatsApp group page (CoE/CAR 2018), created for the course. From day one we have strived to model the main tenets of action research by enacting diverse initiatives to engage the student-teachers and constantly assessing the process by soliciting formal handwritten evaluations of student-teachers of the main course chapters (n=5), process experiences documented in our diaries, and committing to our discussion series. Those intentionally and consistently demonstrated exemplars established the rigor and trustworthiness (Mena & Russel, 2017) of the course, and our self-study among the student-teachers communicated through diverse means and at various stages of the course.

Participants

The authors, whose are experienced in developing relevant pedagogies in teacher education in general and action research in particular, have worked as a close learning community for more than eight years. As a team, we have participated in and led professional development initiatives at various schools in Eritrea among teachers, school leaders, and communities. The interest in developing action research at the colleges started when Berhin, a senior educator and researcher, initiated a structured education program in managing an action research course at the former ACCE in 2014. Khalid, Aman, and Kiflay were participants of the program. The program proved highly empowering in our professional duties and it happened to be the main source of inspiration to continuously develop the course. The student-teachers (n=27), out of which 18 female and 9 male, had a mean age of 22. Only one of the students had school teaching experience. They were in their final college year and were assigned to teach in schools throughout the country after the academic year.

Data and Analysis

We have gone through our reflective notes of the series of focused discussions and have revisited all the audio recorded discussions (n=34) which were in our local, Tigrinya, a language with frequent use of English while discussing terms, issues, concepts, and experiences. To write this article we have focused on 12 sessions documented in 08:30:25 hrs. long audio-recorded discussions. The 12 sessions were selected because they were conducted during major milestones of the course facilitations and were enriched by informative feedbacks of the student-teachers through their formal chapter evaluations and class discussions. We have generated over 19 thousand words of translated text for analysis. Frequent switching to English during the discussions captured key issues which were transcribed as they are and used as data for analysis. Discussions in Tigrinya that were expressive and not readily translatable to English were transcribed as they are. We had to repeatedly revisit the audio-discussions and refer to our reflective notes during the discussions to come up with valid translations while using the texts transcribed in Tigrinya as data for analysis. We have triangulated this data with our diary entries of classroom processes and beyond. The diary of Khalid is used as he was facilitating the student-teachers’ action research projects on site after week 7. Course materials and documents are also used to enrich the analysis.

We have closely read the discussion transcripts in identifying pedagogical episodes that significantly impacted the outcome of the course and continue to inform our teacher education practices, particularly for the first author who continued to lead courses in the newly established postgraduate diploma program in education. Accordingly, “typicality of an incident” (Scott & Morrison, 2005, p. 45) was considered during analysis because they were critical in learning to facilitate the course and had a significant impact on what followed them (Cohen et al., 2018, p. 551). In the context of developing self-study scholarship in teacher education, Berry (2007) discusses how ‘tensions’ identified by teacher-educators from their practices could be used as a means for analyzing experiences.

Tensions serve both as a language for describing practice and as a frame for studying practice. Thus they may be considered a way forward in developing a pedagogy of teacher education that can be shared within the community of teacher educators (Berry, 2007, pp. 132-133).

Typicality of incidents and tensions experienced during our collaborative facilitation practices in supporting student-teachers’ action research engagements facilitated in conceptualizing and communicating (Berry, 2007) two main pedagogical experiences that influenced our roles as educators.

Findings

From Content to Pedagogy of Inquiry

The course was designed to practically learn collaborative inquiry processes by engaging student-teacher teams in hands-on experiences of inquiry through an action research cycle. Accordingly, ample time and space were provided for the student-teachers to learn from practices and processes of inquiry. Table 1 shows the course schedule shared with the student-teachers during the first day of the course (17 September 2018). Note that six weeks were dedicated to interventions allowing the student-teachers to act on their findings. During the course, this was reduced to four weeks due to prolonged mid-exam weeks in the colleges. Student-teachers were organized in six teams during the first week in line with the collaborative imperatives of the course.

Table 1: Course Schedule

|

# |

Presentations and discussions |

Sessions |

Cumulative sessions |

Weeks |

|

00 |

Introduction |

3 |

03 |

01 |

|

01 |

Chapter 1 & 2 Why CAR, Meaning of CAR |

3 |

04 |

02 |

|

02 |

Chapter 3 Problem formulation |

4 |

08 |

03-04 |

|

03 |

Chapter 4 Literature search and review |

1 |

09 |

04 |

|

04 |

Chapter 5 Data collection |

3 |

12 |

04-05 |

|

05 |

Chapter 6 Data analysis |

3 |

15 |

06 |

|

06 |

Chapter 7 Reporting |

3 |

18 |

07 |

|

07 |

Chapter 8 Intervention plan |

3 |

21 |

08 |

|

08 |

Interventions |

Week 09 - 14 |

||

|

09 |

Reporting |

3 |

42 |

15 |

|

10 |

Sharing and reflections |

3 |

45 |

16 |

Hence, context and framework were created for hands-on learning on inquiry which created a challenge for us on how to meaningfully engage the student-teacher teams in the process. Our challenge relates to Berry’s (2007) identified tension of translating intent into action. This tension was captured in one of our discussions.

How do we best engage the [student-teachers]? Which engagement modalities are appropriate? Meaningful answers to these questions should be based on the knowledge of learners, the more we know and think about learners the more we creatively develop engagement modalities […] the number one issue is creating a relationship and that is a critical pedagogic issue [emphasized]… better knowledge and creating relationships with learners leads to developing relevant engagement modalities for individuals and teams of learners suitable to a subject, chapter, topic, issue, etc. […] engagement modalities should be collaboratively developed with learners […] which could be about time, venue, organization or creating a situation (30 October 2018).

A deeper knowledge of student-teachers and intentionally creating constructive relationships were the insights that guided our subsequent actions as we spent time in learning more about the student-teachers and creating time and spaces to support teams. The following extract demonstrates one of such actions.

[…] checking the background profile of our [student-teachers], many of them came from the same school which explains their team formation was based on previous familiarity and convenience […] their grades in biology subjects are also relatively good which shows that they are placed according to their inclinations… (02 November 2018).

This finding was important for us at the time as we were keen to learn how the student-teachers formed their teams because it was influencing their team dynamics. And the student-teachers were particularly concerned with the way courses were handled by respective instructors in their biology classes during their problem formulation stage despite their apparent good background and interest in their subject studies. This knowledge led us to encourage student-teacher teams to make most of their background inclinations in supporting one another by forming collaborative study circles during their interventions. Kahu (2013) argues for a broader conceptual framework beyond respective institutions in critically understanding factors that affect students’ engagements in higher education settings. In addition to learning the background of the student-teachers, we committed to long and consistent guidance sessions during afternoon hours in closely working with the teams and addressing their needs. Coherence and use of guidance sessions as ‘teachable moments’ (Brookfield, 2017) was highlighted in one of our discussions.

Guidance may not have a sustainable impact when it is done sporadically, informal occasions have to be seized or created like what was done [in reference to Khalid’s initiative] with a team of student-teachers in inviting them to further discuss their problem development over tea […] important personal and professional qualities are modeled in such occasions and when guidance is done with modeling its sustainability becomes higher (10 October 2018).

Formal guidance sessions (n=5) were conducted with the six teams during the action research milestones. Informal guidance was encouraged as Khalid started to regularly work in the classroom during afternoons (twice a week) to support the teams. Further interactions were arranged during the weekends and through our virtual platform with Khalid and Sami, particularly during the intervention stage. For example, Sami invited the student-teachers to interact online during the weekends to address concerns and provide support (30 October 2018). Those informal occasions and spaces were important in modeling commitment, teamwork, and critical questioning during the action research processes among the teams.

After week 7, we were explicitly stating to the student-teachers that the main ‘contents’ of our learning would be from the process of carrying out respective action research projects while collecting data, organization & analysis, planning, and carrying out interventions (Diary, 29 November 2018). Hence, teams were required to prepare for briefings during regular class sessions about their projects’ status and enrich their respective projects from ensuing discussions. Making most of the process-based briefings of teams and ensuing class discussions was our emergent pedagogy in learning to support the student-teachers. The following discussion extract shows the recognition of this milestone in our pedagogy.

we will think how to make most of [the briefing and sharing sessions] experiences [...] as we are going from content to pedagogy […] how we are proceeding in this experience will be one of our major [engagement] modalities […] the coming four or five weeks are decisive during the interventions because it is when [the student-teachers] will understand action research practically… (12 November 2018).

Since the six action research projects were intentionally focused on the student-teachers’ own and ongoing processes of learning at the colleges, discussions were shifting from blaming instructors, management and the learning environment to reflexively relevant issues about the role of ‘selves’ in learning (Diary, 12 December 2018). Encouraging learners to focus on inward learning helps them “to work more sensitively and effectively with community participants towards a shared purpose” (Woods, 2015, p. 80).

From Critical Friends to Critical Teams

Critical friendship is a key feature of action research particularly during data collection, analysis, and intervention stages because collaborators need people who are willing and interested to provide constructive criticisms to enrich the validity and reliability of the processes (Sagor, 1992, p. 46). Accordingly, teams were encouraged and supported to make the most and explore deeper practices of critical friendship during the course. This experience may relate to working with the tension of ‘confidence and uncertainty’ as we challenged ourselves and the student-teachers “move away from the confidence of established approaches to teaching to explore new, more uncertain approaches to teacher education” (Berry, 2007, p. 120). The following extract shows how we embraced such tension in our evolving pedagogy.

We could organize the critical friendship experience at four levels: first, they could be critical friends within their teams. We could also let the teams experience how they could be critical for one another, which means becoming critical teams […]. The third level could be inviting learners from other specialization to assess what [student-teacher teams] are doing. The fourth level is if their teachers collaborate they could be invited to be critical friends, in this way the diversity of critical friendship could be explored and experienced… (30 October 2018).

We have taken those levels even further in suggesting to teams to start to be critical to oneself first, involve family members as critical friends, and Khalid and Sami also offered to be critical friends to the teams (WhatsApp group page, 03 November 2018). Exploring wider and deeper levels of critical friendship has resulted in critical incidents in ensuing sessions when teams started to act as critical teams to one another in resolving challenging issues during the action research process. All the names mentioned in the following discussion extracts are pseudonyms.

Critical Incident 1: ‘how could we observe and follow lectures at the same time?’

An interesting issue was raised during [teams’ action research status briefing] session when Elias asked how teams could conduct class observations and follow lectures at the same time […] responses came from student-teachers […] Munira, acknowledging the relevance of the question, shared that her team has adopted observation criteria, she went on by giving an example of how students [in Biology classes] showed particular interest when instructors were talking about nature of exams which led her team to conclude that students are particularly keen about exams […] Biniam has shared how teams should develop recollection skills of events [that transpired during class sessions] by developing note-taking and other recording mechanisms… (23 November 2018).

A critical process issue during data collection was identified, shared, and meaningfully addressed by teams. The student-teachers who provided relevant alternatives to the issue were from different teams which demonstrated, to us, how student-teacher teams could act as critical teams. This experience has reframed our role to focus more on “creating collaborative learning environments where peers can be critical friends” (Wrench & Paige, 2019, p. 4).

Critical Incident 2: Prioritizing Intervention Plans

The following extract shares another critical incident that resulted in redefining the intervention stage of the teams.

Team C have shared how their previous assumptions, that informed their problem formulation, about instructors’ qualification and interest to teach [biology class] courses have been changed after their preliminary findings […] Daniel [Team A] further raised a highly relevant issue about the possibility of developing [intervention] plans that were not necessarily part of the action research process (Diary, 29 November 2018).

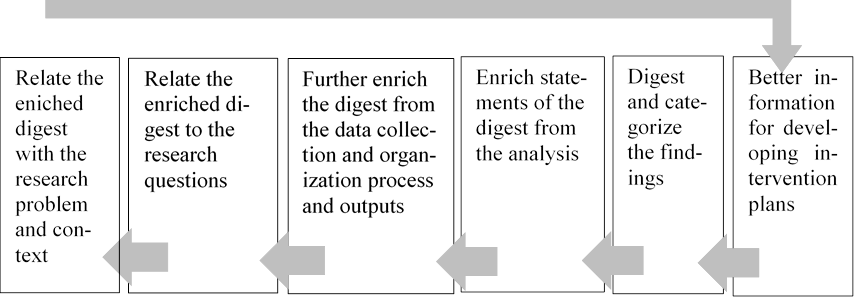

The diary entry points to an intense class session on developing findings-based intervention plans after the first author has proposed a framework (Figure 1) in supporting teams to develop meaningful and actionable plans (Sagor, 1992). The framework suggests that intervention statements should represent and reflect the action research process. At the same time developed plans should be retrospectively related to the action research stages to maintain their focus and integrity. The loop in the model was meant to encourage teams to develop relevant and refined interventions by consolidating on their evolving action research experiences.

Figure 1: A model for retrospectively relating research stages for developing an intervention plan

|

The experiences of Team C and Daniel’s suggestion provided excellent examples in elaborating on the suggested framework. Team C’s experience showed how intervention plans are enriched by findings including teams’ reframed assumptions and research questions. Daniel’s comment was critical because intervention insights that were not considered to be part of the action research processes could still be part of the findings. After all, it could be argued that the process could instigate insights that were not realized during initial phases, hence the need to retrospectively and critically reflect on the action research stages. The comments helped us guide teams to prioritize and focus their intervention plans. We were coming to know the value of supporting student-teachers in utilizing their experiences to inform their learning. Berry (2007) describes this as the tension involved in supporting student-teachers in valuing their experiences and challenging them to reconstruct it. The pedagogical insight emanating from such tension was highlighted in one of our discussions.

The sharing sessions among the researching teams are important because [student-teachers] listen to their own examples more seriously and deeply (29 November 2018).

This pedagogic insight inspired us to be more sensitive and value student-teachers’ questions and suggestions. The upcoming four weeks (week 12-15) were dedicated to more focused briefings and discussion sessions of teams’ respective action research progress, challenges, and issues. Our roles have accordingly shifted to proactively learn and guide emergent process issues with collaborating teams.

Critical Incident 3: Organizing Collaborative Studies

We have encouraged collaborative interventions across teams and student-teachers have creatively adapted interventions by raising critical issues during the process.

Biniam and Beserat [Team A and D respectively] were debating on how to organize collaborative studies which happen to be the main intervention that connects the six teams, Biniam had the view that study collaborators should be intentionally organized based on their inclinations and interests while Beserat’s view was that student-teachers [from six teams] should be randomly placed in study circles to encourage them to come out of comfort zones of their respective teams and expose them with experiences of different teams… (18 December 2018).

The views of the student-teachers were valid. Biniam’s concern was the observed limited structure and intentionality of emergent collaborative study circles (Diary, 11 December 2018) when they are not done voluntarily based on the interests of student-teachers. Beserat’s concern was the risk of missing out on resourceful student-teachers who were not necessarily vocal about their interests or inclinations. Hence, the need for balancing the concerns was emphasized in organizing the collaborative study circles (Diary, 17 December 2018). Again, this was a critical instance of how teams were critically influencing one another in meaningfully progressing and significantly influencing outcomes of their respective projects.

Discussion

This article attempted to describe and analyze the trajectory of pedagogical experiences in collaboratively facilitating and developing a course on inquiry among a senior class of student-teachers. The authors were engaged in self-study of practices that led to the “reframing and reconceptualization” (Klein & Fitzgerald, 2018, p. 30) of roles as educators. We explored pedagogical issues in meaningfully engaging the student-teachers while practicing stages of an action research cycle. Critical incidents identified and analyzed in this article show how our roles were reframing and evolving from facilitators of prescribed contents to co-constructors of learning experiences through committed practices by relating with the backgrounds and needs of the student-teachers. The main tension we experienced in our practice in this regard was enacting our intentions for meaningfully engaging student-teachers in stages of inquiry and interventions. The value of learning student-teachers’ backgrounds and building on their evolving learning experiences was among our emergent pedagogies that were maturing during our collaborative practices. Intentional practices embodied in elaborate course designs are key in ensuring meaningful learning of student-teachers and creating contexts and frameworks for educators to develop scholarships of their complex duties (Loughran, 2014).

Insights matured and developed during the series of discussions were directly feeding into our practices of facilitating the hands-on action research projects of the student-teachers. In turn, genuine engagements of the student-teachers invigorated our self-study practices and inspired us to explore headway pedagogies of possibilities (Ritter et al., 2019). Diverse modes of engagements, including levels of critical friendship, explored and experienced during the course, were based on collaborative initiatives of a community of practice that was sustained over time (Brodie & Boroko, 2016). Emphasizing the collaborative nature of action research and accordingly designing and collaboratively enacting the course from the outset was based on deep convictions that meaningfully changing learning contexts happens collaboratively (Sagor, 1992). What makes action research a ‘research’ “is not the machinery of research techniques but rather an abiding concern with relationships between social and education theory and practice (Balakrishnan & Claiborne, 2017, p. 197).

Action research is increasingly being regarded as strategic in various teacher education programs (e.g., Worku, 2017; Yan, 2017). We argue we should be critical of well-meaning initiatives that attempt to introduce rigorous guidelines while supporting action research projects (Spencer & Molina, 2018) because they may dilute and ultimately domesticate the potential of action research in conforming to authoritative guidelines (Kemmis, 2006). Inspired by our findings, we are more for co-constructing dynamic frameworks from evolving and process-based practices by critically reflecting on the educational value of situated practices (Kemmis et al., 2014). Valuing and prioritizing student-teachers’ evolving experiences during action research projects is needed in empowering them as persons (Korthagen, 2017). Furthermore, our findings reaffirm the modeling of pedagogical intentions among student-teachers as central in developing a pedagogy of teacher education (Korthagen, 2016) and collaborative and improvement imperatives of action research in developing school work practices. Ritter et al. (2019) similarly adapt a modeling framework in their collaborative self-study practices in ‘walking their talk’ among their student-teachers “designed to advance understanding of inquiry as a method of discovery or as a way of being” (p. 150).

Possible implications of our findings to teacher education practices in general and developing action research courses are that educators need not only depend on the existing body of knowledge to inform their practices particularly when they are challenged to improve learning contexts. They should “develop mechanisms to support their growth as they transform their pedagogies of teacher education to embrace practice-based approaches in teacher education” (Peercy & Troyan, 2017, p. 34). Intentionally developing their own pedagogies in teacher education are essential experiences for student-teachers in adapting pedagogical approaches by relying on their own, their learners’, and schools’ resources in their prospective teaching career.

Finally, the article has not analyzed the experiences of the student-teachers during the course through the series of discussions that were informed and enriched by critical feedbacks of the student-teachers throughout the course. The collaboration of colleague educators in supporting teams to carry out their action research projects into their processes of learning was limited despite the intentions of the course. Regardless of these limitations, the article has focused on how the course facilitation experiences have shaped the authors’ roles as educators during the process which continued to have a significant impact in subsequent course engagements in teacher education settings. Future research initiatives could focus on closely aligning the action research of educators and student-teachers into respective learning and teaching practices to enhance and diversify modeling opportunities of educators and develop a pedagogy of action research and teacher education practices. A wider collaboration of colleague educators is important in modeling collaborative ideals of action research and realize its cross-cuttingly empowering potential among student-teachers and K-12 school settings (Vaughan & Burnaford, 2016). Also, it is highly relevant to collaboratively research, preferably with familiar cohorts of student-teachers, on how action research cycles could be sustained in schools in shaping teaching practices.

References

Akyeampong, K., Lussier, K, Pryor, J., & Westbrook, J. (2013). Improving teaching and learning of basic maths and reading in Africa: Does teacher preparation count? International Journal of Educational Development, 33, 272-282. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2012.09.006

Balakrishnan, V., & Claiborne, L. (2017). Participatory action research in culturally complex societies: opportunities and challenges. Educational Action Research, 25(2), 185-202. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2016.1206480

Berry, A. (2007). Reconceptualizing Teacher Educator Knowledge as Tensions: Exploring the tension between valuing and reconstructing experience. Studying Teacher Education, 3(2), 117-134. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425960701656510

Bodone, F., Guðjonsdottir, H., & Dalmau, M. (2004). Revisioning and recreating practice: collaboration in self-study. In J. J. Loughran, M. L. Hamilton, V. L. Laboskey & T. Russell (Eds.), International Handbook of Self-Study of teaching and teacher education practices (Pt. 1, pp. 743-784). Springer.

Brodie, K., & Borko, H. (Eds.) (2016). Professional learning communities in South African schools and teacher education programs. HSRC Press.

Brookfield, S. D. (2017). Becoming a critically reflective teacher (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Bullock, S. M., & Sator, A. (2018). Developing a Pedagogy of “Making” through Collaborative Self-Study. Studying Teacher Education, 14(1), 56-70. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425964.2017.1413342.

Cochran-Smith, M. (2003). Learning and unlearning: the education of teacher educators. Teaching and Teacher Education, 19, 5-28.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. (2004). Practitioner inquiry, knowledge, and university culture. In J. J. Loughran, M. L. Hamilton, V. L. Laboskey & T. Russell (Eds.), International Handbook of Self-Study of teaching and teacher education practices (Pt.1, pp. 601-649). Springer.

Cohen L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research Methods in Education (8th ed.). Routledge.

Cuenca, A. (2010). Self-Study Research: Surfacing the Art of Pedagogy in Teacher Education. Journal of Inquiry and Action in Education, 3(2), 15-29.

Feldman, A., Paugh, P., & Mills, G. (2004). Self-Study through action research. In J. J. Loughran, M. L. Hamilton, V. L. Laboskey & T. Russell (Eds.), International Handbook of Self-Study of teaching and teacher education practices (Pt. 1, pp. 943-977). Springer.

Fletcher, T., Ní Chróinín, D., & O’Sillivan, M. (2016). A layered Approach to critical friendship as a means to support innovation in pre-service teacher education. Studying Teacher Education, 12(3), 302-319. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425964.2016.1228049

Goodwin, A. L., Smith, L., Souto-Manning, M., Cheruvu, R., Tan, M. Y., Reed, R., & Taveras, L. (2014). What Should Teacher Educators Know and Be Able to Do? Perspectives from Practicing Teacher Educators. Journal of Teacher Education, 65(4), 284– 302. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487114535266

Hamilton, M.L., Smith, L., & Worthington, K. (2008). Fitting the Methodology with the Research: An exploration of narrative, self-study and auto-ethnography. Studying Teacher Education, 4(1), 17-28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487114535266

Hargreaves, A. & Fullan, M. (2012). Professional capital: transforming teaching in every school. Teachers College Press.

Idris, K. M., Asfaha, Y. M., & Ibrahim, M. (2017). Teachers ‘voices, challenging teaching contexts and implications for teacher education and development in Eritrea. Journal of Eritrean Studies, III(1), 31-58.

Kahu, E. R. (2013). Framing student engagement in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 38(5), 758-773. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.598505

Kemmis, S. (2006). Participatory action research and the public sphere. Educational Action Research, 14(4), 459-476. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09650790600975593

Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R., & Nixon, R. (2014). The Action Research Planner: Doing Critical Participatory Action research. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-4560-67-2

Klein, J., & Fitzgerald, L. M. (2018). Self-Study, Action Research: Is that a boundary or border or what? In D. Garbett & A. Ovens (Eds.), Pushing boundaries and crossing borders: Self-study as a means for researching pedagogy (pp. 27-33). Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices (S-STEP).

Korthagen, F. A. (2017). Inconvenient truths about teacher learning: towards professional development 3.0. Teachers and Teaching, 23 (4), 387-405. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1211523

Korthagen, F. A. (2016). Pedagogy of Teacher Education. In J. Loughran & M.L. Hamilton (Eds.), International Handbook of Teacher Education (vol. 1, pp. 311-346). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0366-0_8

LaBoskey, V. K. (2004). The methodology of self-study and its theoretical underpinnings. In J. J. Loughran, M. L. Hamilton, V. L. Laboskey, & T. Russell (Eds.), International Handbook of Self-Study of teaching and teacher education practices (Pt. 1, pp. 817-869). Springer.

Loughran, J. (2014). Professionally developing as a teacher educator. Journal of Teacher Education, 65(4), 271-283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487114533386

Mena, J., & Russel, T. (2017). Collaboration, multiple methods, and trustworthiness: Issues arising from the 2014 international conference on self-study of teacher education practice. Studying Teacher Education, 13(1), 105-122. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425964.2017.1287694

Mtika, P., & Gates, P. (2010). Developing learner-centered education among secondary trainee teachers in Malawi: The dilemma of appropriation and application. International Journal of Educational Development, 30, 396-404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2009.12.004

Pellerin, M., & Paukner, F. I. (2015). Becoming reflective and inquiring teachers: collaborative action research for in-service Chilean teachers. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 17(3), 13-27. https://redie.uabc.mx/vol17no3/contents-pellerin-paukner.html

Peercy M. M., & Troyan, F. J. (2017). Making transparent the challenges of developing a practice-based pedagogy of teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 61, 26-36. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.10.005

Ping, C., Schellings, G., & Beijaard, D. (2018). Teacher educators’ professional learning: A literature review. Teaching and teacher education, 75, 93-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.06.003

Ritter, R., Ayieko, R. Vanorsdale, C., Quiñones, S., Chao, X., Meidl, C., Mahalingappa, L. Meyer, C., & Williams, J. (2019). Facilitating Pedagogies of Possibility in Teacher Education: Experiences of Faculty Members in a Self-Study Learning Group. Journal of Inquiry & Action in Education, 10(2), 134-157.

Sagor, R. (1992). How to conduct collaborative action research. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Schuck, S., & Russell, T. (2005). Self-Study, Critical Friendship, and the Complexities of Teacher education. Studying Teacher Education, 1(2), 107-121. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425960500288291

Scott, D., & Morrison, M. (2005). Key Ideas in Educational Research. Continuum International Publishing Group.

Spencer, J. A., & Molina, S. C. (2018). Mentoring graduate students through the action research journey using guiding principles. Educational Action Research, 26(1), 144-165. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2017.1284013

Vaughan, M., & Burnaford, G. (2016). Action research in graduate teacher education: a review of the literature 2000–2015. Educational Action Research, 24(2), 280-299. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2015.1062408

Vavrus, F., Thomas, M., & Bartlett, L. (2011). Ensuring quality by attending to inquiry: Learner-centered pedagogy in sub-Saharan Africa. UNESCO CBA International Institute for Capacity Building in Africa.

Westbrook, J., Durrani N., Brown, R., Orr, D., Pryor, J., Boddy, J., & Salvi, F. (2013). Pedagogy, Curriculum, Teaching Practices and Teacher Education in Developing Countries. Final Report. Education Rigorous Literature Review. EPPI-Centre. ISBN: 978-1-907345-64-7

Wood, L. (2015). Reflecting on reflecting: fostering student capacity for critical reflection in an action research project. Educational Research for Social Change, 4(1), 79-93. ISSN: 2221-4070

Worku, M. Y. (2017). Improving primary school practice and school–college linkage in Ethiopia through collaborative action research, Educational Action Research, 25(5), 737-754. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2016.1267656

Wrench, A., & Paige, K. (2019). Educating pre-service teachers: towards a critical inquiry workforce. Educational Action Research. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2019.159387

Yan, C. (2017). ‘You never know what research is like unless you’ve done it!’ Action research to promote collaborative student-teacher research. Educational Action Research, 25(5), 704-719. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2016.1245155