http://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.4155

Cai Yuanpei’s Vision of Aesthetic Education and His Legacy in Modern China

Ning LUO[1]

The Education University of Hong Kong

Abstract

Cai Yuanpei is widely understood to have been a traditionally educated Chinese scholar who then turned his attention to Western philosophy. He is known to have played a central role in the development of Republican educational philosophies and institutions, with a legacy that continues to inform education in China. Studies tend to interpret Cai Yuanpei’s approach to aesthetic education in light of his educational experience in Germany, regarding him as a Kantian scholar. However, the Confucian roots of his aesthetic education seldom draw scholarly attention. To fill the gap, this article examines Cai’s vision of aesthetic education based on both his academic background in the East and his knowledge of Western philosophy and maps out his influence on and legacy in aesthetic education in China. It argues that Cai’s vision of aesthetic education has influenced modern Chinese education in three main ways: by bridging the gap between moral education and aesthetic education to nurture citizenship, by encouraging aesthetic education for whole-person development, and by adopting an interdisciplinary approach to school aesthetic education. The article concludes by reflecting on the enduring value of Cai’s vision of aesthetic education to modern Chinese education.

Keywords: Cai Yuanpei, aesthetic education, China, humanism, social harmony

Introduction

Cai Yuanpei (蔡元培, 1868–1940) was a prominent figure in 20th-century China who served as the first Minister of Education of the Republic of China (ROC) and initiated modern education reforms nationwide. Aesthetic education (meiyu, 美育) was at the core of these reforms and continues to have a profound influence on China’s educational philosophy, policies, and practices. Cai interpreted aesthetics (meixue, 美學) as art appreciation and perceptual enlightenment, and aesthetic education involves affective ways of learning, including thinking with images, observational processing leads to insights into artworks, social issues and the natural environment (Cai, 1983). Although Cai served as an official in the government of the ROC, which was replaced by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the early 1950s, he was held in high regard by the PRC government, and his vision of aesthetic education was adopted by PRC officials. In 2007, Peking University, one of the most prestigious universities in China, established Yuanpei College[2] (元培學院) to honour Cai Yuanpei’s contribution to modern Chinese education. Examining Cai’s vision of aesthetic education casts light on arts education in today’s China.

After being educated in the Confucian tradition, Cai proceeded to Hanlin Academy (翰林院), which was the premier institution for academic officials located near the Forbidden City in the late Qing Dynasty (Duiker, 1971). While serving in the corrupt Qing government, Cai reflected deeply on traditional Confucian teaching and advocated for social reform (Duiker, 1971). To learn from modern Western thinking, Cai spent several years in Germany (1907–1912), during which he studied philosophy, education, anthropology, and psychology at the university level – knowledge that he considered helpful toward building a modern China (Duiker, 1972). In 1912, the year in which the ROC government was founded, he returned to China and was appointed Minister of Education by the leader of the ROC, Sun Yat-sen (Liu, 2019). Cai’s successful career in the administration gave him opportunities to put his philosophy into practice, especially his vision of aesthetic education.

The aesthetic education proposed by Cai Yuanpei is a popular topic of Chinese scholarship. According to a comprehensive annual review of research on aesthetic education in China, Cai’s thoughts on aesthetics draw the most attention (Yang & Li, 2019). However, the literature regarding Cai’s theory tends to trace his ideas about aesthetics back to his educational experience in Germany, thus identifying him as a Kantian scholar (Wang, 2020). It also overlooks the connection of his theory with modern educational practice (Liu, 2019). This article aims to fill these gaps by examining Cai’s vision of aesthetic education based on his academic background in the East and his knowledge of Western philosophy, and by mapping out his influence on and legacy in aesthetic education in China.

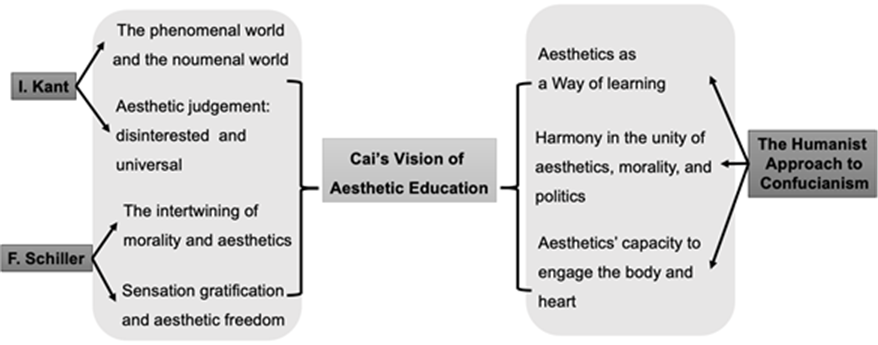

This article begins with a brief introduction to Cai Yuanpei’s early life and academic experience, followed by a discussion of his thinking, which was rooted in humanist Confucianism and the philosophies of Immanuel Kant and Friedrich Schiller, the two Western philosophers most prominently referenced in Cai’s speech and writings (Cai, 1983; Peng, 2018). The next section summarises his policies regarding aesthetic education in the school, family, and social domains, which can be collectively understood as socially-oriented aesthetic education. The last section explores how Cai’s ideas have been put into practice in modern China. The article concludes by reflecting on the enduring value of Cai’s vision of aesthetic education in modern Chinese education.

Early Life Experience

Cai’s early experience had a profound impact on his later thoughts on how to transform Chinese society. He was born during the late Qing Dynasty and spent his youth in Zhejiang (浙江), on the south-eastern coast of China, one of the few areas where people could trade with the West. Western ideology travelled alongside commercial trade and made these regions into the birthplace of modernity in China (Liu, 2019). Although Cai received a traditional education in his youth, like many of his contemporaries, he showed a strong interest in Western ideology (Wang, 2020). For instance, when he began his service as an official in 1894, he advocated for the integration of science subjects into the teaching of the Hanlin Academy, the most prestigious royal institution for academic officials in the late Qing Dynasty (Duiker, 1971)

The proposed introduction of science to the Hanlin Academy was Cai’s first attempt to enact reform within the imperial system. However, he was disillusioned by his experience of the Qing government, and his reform failed. He then moved to Shanghai, an open coastal city, where he became a member of the Revolutionary Party (Liu, 2019). Cai was obliged to flee to Germany, where he studied philosophy at Leipzig University from 1907 to 1911 (Duiker, 1971). He returned to China to serve as Minister of Education in the newly founded Republican government in 1912. However, the corruption in the government disappointed him, and he resigned and returned to Germany to continue his academic life (Liu, 2019). In 1916, he returned to China at the invitation of the reformed government and became the president of Peking University (Duiker, 1971).

During the first half of his life, Cai witnessed the collapse of the Confucian order, the military and intellectual challenges posed by the West, and the growth of a market society in China. He also experienced social crises, intellectual self-doubt, economic recession, and the rise of fascism in Western society after World War I. His early educational background in Confucian philosophy and his later academic experience in Europe provided him with a comprehensive worldview that served as a basis for the creation of a new Chinese society.

During his early years of learning in Germany, Cai was deeply concerned about the moral decay of his time, and he regarded aesthetic education as a promising means of social reformation. Cai attempted to synthesise the best values of traditional Chinese philosophy with modern Western ideology. He found that aesthetics could link the spiritual world to the physical world and build moral behaviours, as suggested both by Confucian thinking and by German philosophers.

Figure 1. Cai Yuanpei

Unlike other leading activists in the New Culture Movement, a cultural and social undertaking to abolish the Confucian order in China in the early 20th century, Cai received a comprehensive traditional education in his youth. At the age of 24, Cai enrolled in Hanlin Academy after passing a highly competitive examination (Duiker, 1971). From this perspective, Cai was a great success within the traditional education system and was regarded as an accomplished Confucian scholar by his peers. He also admitted that his early years of Confucian learning sparked his later interest in moral issues, with a distinct emphasis on self-cultivation and social obligation (Duiker, 1971). Therefore, unlike many other activists in the New Cultural Movement, who took a radical attitude towards Westernisation and the overthrow of traditional China, Cai was an accomplished Confucian scholar who saw the value of traditional ideology and took a humanist Confucian approach to aesthetics.

Philosophical Roots of Cai’s Reform

Cai’s vision of aesthetic education as social reform originated from his academic background. Cai’s deep concern about the moral decay of his time led him to think about how to rejuvenate Chinese society. Among other approaches, he believed that aesthetics, which is associated with the affective realm, could serve the purpose of cultivating emotion and shaping a new morality (Cai, 1983). This vision of aesthetic education was rooted in Confucian teaching on aesthetics in combination with Cai’s learning from the Western philosophers Immanuel Kant and Friedrich Schiller.

Confucian Teaching on Aesthetics

Cai is not usually viewed as a supporter of Confucianism, because he advocated for the New Culture Movement and against the traditional order of Chinese society supported by Confucian ideology. However, from another perspective, he was an accomplished Confucian scholar in 20th-century China who applied the humanist Confucian approach to reform society. During his time, there were two Confucian schools of thought – authoritarian and humanist (Duiker, 1971). Both schools served to maintain the hierarchy of imperial society; however, whereas the authoritarian school imposed social and political pressure on individuals, humanists believed in the good side of human nature. They believed that individuals can best be led to follow dao (道, the Way) via education – thus adhering to the original teachings of Confucius and his successor Mencius (Duiker, 1971). Cai was an advocate of the humanist view and had demonstrated an interest in this approach since his youth (Duiker, 1971). According to the humanist school, to follow the Way is to manifest the function of jiao hua (教化, educating), which resembles the German term Bildung, in that both imply self-cultivation and harmonic growth (Danner, 1994; Tu, 1989).

Cai and Confucius agreed that becoming fully human requires an internal transformation that can be best achieved through aesthetic experience. Cai adopted Confucian teaching on aesthetics in three main ways – learning via aesthetic activity; finding harmony in the unity of aesthetics, morality, and politics; and making use of aesthetics’ capacity to engage one’s body and heart.

Aesthetics as a Way of Learning. In both Cai’s and Confucian thought, aesthetic experience facilitates behaviour that follows the Way and enhances the function of jiao hua. Art played a significant role in Confucian thought, and the early Confucians were artists, mastering ritual actions and engaging in a wide array of aesthetic activities, such as music, poetry, and calligraphy (Mullis, 2005). However, mastering art skills was not the main purpose of engaging in such activities; rather, it aimed to shape people’s character through aesthetic activities. For instance, Confucius viewed aesthetic education as a means of self-cultivation, ‘which starts with the study of poetry, then moves to the study of rituals, and then towards accomplishment in the study of music’ (興於詩, 立於禮, 成於樂) (Analects 8.8). This saying underlines that the purpose of learning shi (詩, poetry) is to develop people’s will to promote their self-consciousness and empathy. The next phase is to achieve self-reliance by learning and practising li (禮, rituals), which help one become a responsible member of the community. Finally, through yue (樂, music) education, one can achieve self-cultivation and approach the status of junzi (君子, a superior person).

Harmony in the Unity of Aesthetics, Morality, and Politics. Cai had a hierarchical mission for aesthetic education. In his arguments regarding the usefulness of aesthetics, Cai asked the following question: ‘how can we turn the desire for beauty into self-cultivation and moral perfection, and eventually contribute to a harmonious society?’ (Cai, 1983, p. 1). Cai’s discourse on harmony is in line with the Confucian concept of he (和, harmony), which is deeply embedded in Chinese culture and has influenced how morality and education are conceptualised (Feng & Newton, 2012). Methodologically, a traditional Chinese view of harmony acknowledges this virtue as ‘a preference for negotiation over a fight, reform over revolution, and eclecticism over dogma’ (Feng & Newton, 2012, p. 342). In an ontological sense, harmony is at the core of Confucianism, and itself manifests divine wisdom (Tu, 1989). Yueji (樂經, The Book of Music), the only text of Confucian teaching on music, defined yue (樂,music) as a privileged form of sound that can only be properly performed and appreciated by junzi, claiming that ‘a superior person goes against the natural dispositions to harmonise his aspirations’ (The Book of Ritual 19.5). Therefore, for both Cai Yuanpei and Confucius, art took on political and moral undertones, as a means to educate individuals to regulate their personal desires and pursue harmonious relationships between self, others, and society.

Aesthetics’ Capacity to Engage Both Body and Heart. Cai acknowledged the capacity of aesthetics to engage people’s bodily and sensuous experiences, in turn regulating their moral behaviour. He offered the example of ritual and music in Confucian teaching to support this point:

On one hand, in the natural environment, music is the harmony of natural sounds which do not imply sadness or joy; on the other hand, in the ritual ceremony, certain music can evoke emotions that originate from the listener’s heart, which embodies another kind of harmony that bridges the gap between the body and the heart (Cai, 1983, p. 54).

This capacity was also mentioned in various Confucian texts. In Discourse on Music, for example, Xunzi (313–238 BCE) wrote ‘where there is music, it will issue forth in the sounds and manifest in the movement of the body’ (Xunzi 20.2). Similarly, Mencius stated that ‘when listening to music, people quite unconsciously find that their feet begin to dance and hands begin to move’ (Menzi 29.15). In addition, Confucius offered an interesting example of how aesthetic experience had influenced his appetite, saying, ‘I could not discern the taste of meat for months after I learned this beautiful piece of music’ (Analects 7.14). In this Confucian discourse, music is valued more than simply as sound and patterns; it is a product of aesthetics, morality, and politics, in which the body and heart of the listener are fully engaged and directed towards moral and prosocial behaviours and mindsets (Wang, 2020).

Learning from Kant and Schiller

Of the European philosophers from whom Cai gained knowledge, he considered Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) and Friedrich Schiller (1759–1805) the most important masters of aesthetics, stating that

Since Baumgarten (1717–1762) established aesthetics, Kant and his Critique of Judgment contributed the most to its discourse and system, and Schiller was the person who further developed aesthetics from the perspective of moral and ethics, laying the ground for aesthetic education (Cai, 1983, p. 66).

Cai adopted Kant’s dualistic standpoint of the phenomenal world and the noumenal world, arguing that ‘aesthetics would bridge the two worlds and transcend human experience’ (Cai, 1983, p. 4). In education, the phenomenal world concerns the material goals of making students productive members of society, while the noumenal world, the ‘thing-in-itself’ (Zarrow, 2019, p. 154) in Kantian philosophy, are viewed as fundamental goals of education, which is about ‘morality or transcendental laws’ (You et al, 2018, p. 260). Cai specified that ‘the ultimate goal of the phenomenal world is to return toward the noumenal world’ (Cai, 1983, p. 5). He argued that aesthetic experience embodies this transcendent quality and that the ultimate goal of aesthetic education is to lead people into the spiritual realm, which will help them achieve spiritual freedom and become moral citizens (Cai, 1983). To strengthen his argument for the transcendent quality of aesthetic experience, Cai borrowed from Kant the two key features of aesthetic judgement, disinterested and universal, claiming that ‘aesthetics could help to develop humanism because of its disinterested and universal features would transcendent the self-centred personality’ (Cai, 1983, p. 56). In other words, Cai believed that aesthetic experience could reduce people’s selfishness and prejudices in the phenomenal world and promote a feeling of the sublime that could transcend the material world of mundane concerns.

Although Cai adopted Kant’s ontological understanding of the nature of the world and the essence of aesthetic judgement, his thoughts on the intertwining of morality and aesthetics came from Schiller (Cai, 1983). In his aesthetic discourse, Schiller reflected on the ways that the body and sensations could be educated to attain collective rules and maintain a bourgeois social order. Aesthetic education would allow for sensory gratification and aesthetic freedom, which were regarded as a solution to political problems. As Schiller (2004) stated, ‘If we are to solve political problems in practice, follow the path of aesthetics since it is through beauty that we will arrive at freedom’ (p. 27). Similarly, Cai’s objectives for aesthetic education were to achieve moral perfection and to create an environment conducive to political engagement (Cai, 1983). However, unlike the disconnection of the phenomenal and noumenal worlds held by Kant and Schiller, Cai (1983) argued that the two worlds are the two sides of one world that complementary to each other in human’s perception, because ‘we perceive the world materially and immaterially’ (p. 4). This argument is underpinned by the ontological holism in traditional Chinese philosophy, originating from the dialectical relationship between spiritual and phenomenal worlds (Liu, 2019).

Figure 2. Origins of Cai’s Vision of Aesthetic Education

Socially Oriented Aesthetic Education

Cai Yuanpei argued that aesthetic experience could help to solve moral problems and purge politics for the sake of modern society (Cai, 1983). It offered a possible solution to the moral decay that could foster civic virtue and build a democratic society. Cai showed no interest in the formalist aesthetics of art for art’s sake, nor was he interested in aesthetics merely for sensory satisfaction (Cai, 1983). He believed that aesthetic education was intended to instil a humanist worldview, promote public morality, and nurture people’s emotional and rational personalities. These characteristics were considered fundamental to modern citizenship and essential to the new Republican politics in China (Cai, 1983). In the early 20th century, the transformational era of Chinese society, modernised reform denied the old morality, which was bound to a hierarchical network of kinship, whereas the new order had not yet been established.

As the Minister of Education in the newly founded government, Cai was a visionary reformer who promoted aesthetic education in parallel with physical, intellectual, ethical, and worldview education in the Educational Proclamation issued by the first Republican government in September 1912 (Duiker, 1972). The five components of education, named wuyu gingju (五育並舉, ‘education in five aspects’), gave the arts an unprecedented role in Chinese educational policies that even today serves as a key element of the Chinese nine-year compulsory education system (Ministry of Education, 2011). Aesthetic education was emphasised because it could ‘cultivate good character in the Republic’s citizens’ (Cai, 1983, p. 68). Specifically, Cai’s proposals for aesthetic education were grounded in the school, family, and social domains.

School and Family Aesthetic Education

Regarding school education, from kindergarten through university, Cai proposed that aesthetics did not consist solely of art, music, and literature curriculums, but was part of every aspect of school life (Cai, 1983). In other words, aesthetic education was not a synonym for art education; rather, it was a broad concept embedded in the school curriculum. For mathematics and chemistry, for example, ‘the mathematical law of geometry is embedded in aesthetics; chemistry is closely related to the beauty of colour’ (Cai, 1983, p. 136). This interdisciplinary perspective is similar to the recent movement (in response to STEM) of science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics (STEAM) education today. Cai further suggested that teachers should use aesthetics to facilitate students’ learning and stressed the importance of maintaining a pleasant campus environment (Cai, 1983). He also felt that environmental aesthetics played a significant role in the family domain, in which people spend the most time. He stated that ‘no matter how expensive the furniture is, the living room should always be clean and tidy and the arrangement of things should enable a sense of beauty’ (Cai, 1983, p. 137).

Aesthetic Education in Society

Unlike the bourgeois ideology, in which aesthetic education is aimed at elites, Cai proposed that ‘aesthetic experience should be promoted in the public sphere where everyone can get access to museums, parks, and theatres’ (Cai, 1983, p. 221). He raised money to establish art centres in the community and advocated art as leisure for citizens, urging them to contemplate artworks in concert halls and museums and recommending the equal distribution of material and aesthetic goods. Well-designed urban infrastructure, he believed, was important, as clean and tidy streets and parks would offer an aesthetic approach to fostering civic behaviour (Cai, 1983). They would provide an enjoyable public space, foster shared values, and eradicate the backward and immoral behaviours that persisted in traditional Chinese society, such as gambling, prostitution, and smoking opium (Cai, 1983). In addition, Cai was among the founders of a prestigious visual arts academy that nurtured many talented Chinese artists – the China Central Academy of Fine Arts (Cao, 2018). He also established various arts-related communities (e.g., music, Chinese painting, and calligraphy) as grassroots units intended to bring together progressive artists (Cai, 1983).

Cai’s Legacy in Modern China

Cai’s vision of aesthetic education has had a profound impact on modern Chinese educational policies. A systematic investigation of his influence helps to explain the educational practice in China. Aesthetic education is an important component in the Chinese public education domain, which was highlighted in the conference of the Ministry of Education in 1951 (Ministry of Education, 2015). It was the first official conference about national education policy-making after the establishment of the PRC government. In China, aesthetic education is not a subdomain of arts education but rather serves as an educational priority in parallel with intellectual, moral, and physical education, which was explicitly noted in the documents issued after the conference held in 1951 (Ministry of Education, 2015). It then became the cornerstone of ‘Comprehensive Education’ (quanmian jiaoyu, 全面教育) and ‘Quality Education’ (suzhi jiaoy, 素質教育)[3] proposed by the Ministry of education in the late 1980s to the late 1990s. The concept of Comprehensive Education first appeared in the Compulsory Education Law of the People's Republic of China promulgated on July 1, 1986 (Ministry of Education, 2015a). However, this concept has not been fully developed not until on 13th June 1999, the State Council issued Policy of Education Reform and Promoting Quality Education, offering a series of approaches to reform public education to change the examination-oriented ideology (Dello-Iacovo, 2009). In particular, it emphasised the role of aesthetic education to ensure the quality of public education. The high status of aesthetic education was inherited from Cai’s vision and is manifested in two ways: bridging the gap between moral education and aesthetic education to nurture citizenship and aesthetic education for whole-person development.

The conjunction of Moral Education and Aesthetic Education to Nurture Citizenship

Cai’s vision of aesthetic education was intended to provide a moral basis for society (Duiker, 1972). The Chinese translation of ‘aesthetic education’ (美育) was introduced by Cai in 1912, from the German term Asthetische Erziehung. In his interpretation of the concept of aesthetic education, Cai (1983) explained that ‘aesthetics is a means of transcending materialism… appreciating art could help to describe the nature of the real world and elevate its understanding in human society’ (p. 461). For Cai, the appreciation of beauty could reduce prejudice, and aesthetic education was thus the best approach to connect people with the noumenal world (the definition is provided on page 13 when the term first appeared). This interpretation laid the ground for the conjunction of moral education and aesthetic education in Chinese discourse, which is manifested in China’s educational policies. The most recent educational policy issued by the State Council of the PRC (2020), addressing the nature of aesthetic education, noted that

aesthetics and morality are intertwined. Aesthetic education is about beauty, morally good and spiritual… Aesthetics is closely related to students’ spiritual, emotional and character development. It can improve the sense of aesthetic quality, cultivate moral behaviour and promote social cohesion (p. 1).

In this statement, aesthetic education is a way to promote social harmony because aesthetics can nurture a moral citizenry by connecting the physical world and the spiritual world. This is a legacy of Cai’s explanation of the function of aesthetics: to bridge the gap between the phenomenal world and the noumenal world.

Cai’s vision of aesthetic education addressed not only the moral identity of modern women and men but also retained traditional moral components (Wang, 2020). In the early 20th century, when Chinese authorities first sought reformation under the massive cultural and economic invasion of the West, many intellectuals advocated for the replacement of traditional Chinese philosophy with modern Western ideologies and thus the formation of a new moral basis for a common social identity. However, Cai opposed this call, believing that a philosophy that retained the positive parts of traditional Chinese teachings would be the most practical solution for the new society (Duiker, 1972). Although this vision could not be put into practice due to the corruption of the Republican government, it has attracted scholarly interest in the new century and become a mainstream topic of debate among modern Chinese intellectuals on the ideologies of the East and West (Zuo, 2018).

This synthetic view is also consistent with a national cultural campaign endorsed by the PRC government: the new trend of reviving Chinese traditional culture in education. Since 2013, the PRC government has enacted several cultural and educational policies to promote the integration of traditional Chinese culture into aesthetic education. For instance, the National Standards for Visual Arts highlighted a community-based approach to teaching art, namely ‘employing local and traditional art and materials to enrich students’ aesthetic experience and develop a sense of community’ (Ministry of Education, 2011, p. 2). That is, art education is not simply about learning artistic skills; it also has the aim of nurturing community membership via appreciation of local and traditional arts.

Aesthetic Education for Whole-person Development

In China, aesthetics does not comprise a subdomain of arts education; rather, it is an educational objective regarded as essential for whole-person development in school education (Ministry of Education, 2011; State Council, 2020). This educational policy was adopted directly from Cai’s vision of ‘education in five aspects’, of which aesthetic education was one (Cai, 1983). As the Minister of Education in the newly founded government, Cai was a visionary reformer who placed aesthetic education in parallel with physical, intellectual, moral, and worldview education in the Educational Proclamation issued by China’s first Republican government in September 1912 (Duiker, 1972). This proclamation is still a key element of the Chinese compulsory education system (Ministry of Education, 2011).

As stated above, Cai’s vision of aesthetic education was rooted in Confucian teaching, which emphasised comprehensive mastery of the ‘Six Arts’ (六藝)[4], the process of becoming junzi (君子), an ideal member of society and a moral exemplar for others (Li & Xue, 2020). For those who master the Six Arts, the important issue is not whether they can perform the best in the arts, but rather that they live a life that follows the ‘way of truth’ (道) and advances physically and mentally. This view is evident in Chinese national education policies; in the first version of the educational objectives issued by the Minister of Education of the PRC in 1950, aesthetic education was highlighted and placed in parallel with the mastery of knowledge and skills to foster the development of well-rounded people (Li & Hasan, 2013).

Moreover,the interdisciplinary vision of technology and aesthetic education outlined by Cai in the early 20th century was also included in contemporary Chinese art education. In Cai’s vision, technology alone was not enough to make a better China; as a human endeavour, technology should serve the purposes of human ends, and aesthetics are embedded in humanity, which should thus be integrated with technology education in schools (Cai, 1983). This view is evident in modern Chinese education reform, such as the recent emphasis on STEAM education which seeks to offer new space for arts subjects. For instance, in 2015, the Ministry of Education issued an educational plan on science and technology and introduced STEAM education as a curriculum model (Ministry of Education, 2015b). This was also endorsed by the policy issued by the State Council (2015), stating that ‘school subjects should be integrated with aesthetics for the comprehensiveness of the curriculum…Teachers should integrate aesthetic education with mathematics, physics and other science disciplines and develop extracurricular activities to enrich students’ campus life’ (p. 2).

Concluding Remarks

This article examined Cai Yuanpei’s vision of aesthetic education, which is rooted in the humanist strain of Confucianism, the branch of Confucian tradition that is closest to the original Confucian–Mencian model. It advocates faith in the good side of human nature and combines self-cultivation and social obligation. Cai combined this strain of Confucianism with Western aesthetics to arrive at his formula for Chinese modern education, which has had a great influence on modern Chinese education.

Although Cai adopted the humanist strain of Confucianism in his proposals for aesthetic education, it is important to note that as the first Minister of Education, one of his contributions to the educational system was to de-Confucianise the national curricula. This groundwork did not seek to overthrow the essence of Confucian philosophy; rather, it was a systemic reform that sought to eliminate the institutional constraints imposed by the imperial order. Some may argue that all in all, Confucianism was developed to serve the imperial system. For example, the anti-traditionalists involved in the May Fourth Movement contended that the ideology that supported the imperial system should be abandoned in modern China. Cai believed otherwise. His experience in Europe, where he had witnessed World War I, had led him to value the humanist strain of Confucianism; therefore, he advocated for an intercultural perspective, which he felt would best serve the needs of Chinese society. Based on his unique academic background, Cai tried to synthesise Western knowledge with Chinese knowledge, declaring that ‘we should learn and integrate Western thoughts and borrow their good qualities to strengthen our own’ (Cai, 1983, p. 28).

Cai’s views on cultural interchange were visionary in the sense that they embodied cherished faith in the humanist strain of Confucianism for a harmonious society. During China’s Republican period, a time of immense political uncertainty, education reform was not the priority; therefore, few of his plans were put into practice in that period. However, in the long run, Cai’s thinking set the tone for modern education in China, and his vision of a moral and democratic Chinese society has enduring value.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Prof. David Hebert and the classmates from the course entitled Non-Western Educational Philosophies and Policy for their suggestions and thoughtful feedback.

References

Cai, Y. P. (1983). Cai Yuanpei meixue wenxuan [On aesthetics]. Beijing University Press.

Cao, Q. H. (2018). Caiyuanpei de meiyu lantu jiqi dui guoli meishu xuexiao chuangban de tuidong [Cai Yuanpei's vison of aesthetic education and the establishment of national art school]. Meishu, 1, 8-13.

Danner, H. (1994). Bildung: A basic term of German education. Educational Sciences, 9.

Dello-Iacovo, B. (2009). Curriculum reform and ‘quality education’ in China: An overview. International journal of educational development, 29(3), 241-249.

Duiker, W. J. (1971). Ts' ai Yuan-p'ei and the Confucian Heritage. Modern Asian Studies, 5(3), 207-226.

Duiker, W. J. (1972). The aesthetics philosophy of Ts' ai Yuan-p'ei. Philosophy East and West, 22(4), 385-401.

Feng, L., & Newton, D. (2012). Some implications for moral education of the Confucian principle of harmony: learning from sustainability education practice in China. Journal of Moral Education, 41(3), 341-351.

Li, J., & Xue, E. (2020). Shaping the aesthetic education in China: Policies and concerns. In J. Li & E. Xue (Eds.), Exploring education policy in a globalized world: Concepts, contexts, and practices (pp. 127-153). Springer.

Li, L. M., & Hasan, A. N. (2013). Aesthetic education in China. International Journal of Social Science and Education, 4(1), 305-309.

Liu, J. G. (2019). Caiyuanpei de meiyu lilun dao zhonghua meiyu jingshen [From Cai Yuanpei's aesthetic theory to Chinese aesthetic spirit]. Meishu yanjiu, 4, 5-7.

Ministry of Education (2011). National standards for visual arts. Beijing Normal University Press.

Ministry of Education (2015a). Summary of important events of national education policy in fifty years. http://old.moe.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/moe_163/200408/3444.html

Ministry of Education (2015b). The guiding of the development of IT education during the 13th Five Year Plan. http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A16/s3342/201509/t20150907_206045.html

Mullis, E. C. (2005). Carrying the Jade Tablet: A Consideration of Confucian Artistry. Contemporary Aesthetics, 3(1), 13-20.

Peng, F. (2018). Chongsi yi meiyu dai zongjiao [Rethinking replacing religion with aesthetic education]. Meishu, 2, 8-11.

Schiller, F. (2004). On the aesthetic education of man (R. Snell, Trans,). Courier Corporation.

State Council (2015). Comprehensively strengthening and improving aesthetic education in schools. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/201509/28/content_10196.htm

State Council (2020). On strengthening and improving school aesthetic education in the new era. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2020-10/15/content_5551609.htm

Tu, W. M. (1989) A revised and enlarged edition of centrality and commonality: An essay on Chung-yung. State University of New York Press.

Wang, B. (2020). Aesthetics, morality, and the modern community: Wang Guowei, Cai Yuanpei, and Lu Xun. Critical Inquiry, 46(3), 496-514.

Yang, J. C. & Li, Q. B. (2019). Zhongguo meiyu yanjiu 2018 niandu baogao [2018 annual report of Chinese Aesthetic Education Research]. Meiyu xuekan, 1(1), 38-45.

You, Z., Rud, A. G., & Hu, Y. (2018). The philosophy of Chinese moral education: A history. Springer.

Zarrow, P. (2019). A question of civil religion: Three case studies in the intellectual history of" May Fourth". Twentieth-Century China, 44(2), 150-160.

Zuo, J. F. (2018). Cai Yuanpei’s thought of aesthetic education and orthodox Confucianism. Journal of Northwest University, 3, 137-142.