https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.4937

Article

Agency is an illusion: Barriers to participation in teacher education and schools

Solveig Maria Magerøy

University of South-Eastern Norway

Email: solveig.mageroy@usn.no

Abstract

This article investigates student teachers’ perceptions and experiences in teacher education regarding codetermination and participation as a part of education for democracy and citizenship, along with how they visualize their future teaching in this interdisciplinary theme as teachers in schools. The data material includes 16 extensive interviews with six student teachers in their final year of teacher education in Norway. The results demonstrate a discrepancy between their perceptions and praxis concerning participation. First, the student teachers in their last year of teacher education felt the ability to participate in and through their education was present, but they chose not to take advantage of this possibility. They underlined the importance of participation and agency in education for democracy but did not seem to assign the same importance to their involvement in education. Second, when visualizing how to teach democracy and citizenship in schools, they suggested facilitating pupils’ self-determination in situations where the pupils’ decisions and participation do not change or impact anything. In so doing, they described participation and agency as an illusion; something that is important, necessary, and valuable but with no practical implications. The student teachers seemed to transfer this same illusion of pupils’ agency and participation in their planned teaching in the future.

Keywords: democracy and citizenship, education, teacher education, student teachers, participation, agency, teaching democratically

Introduction

Democratic education is highly relevant in these turbulent times with polarized stances, antidemocratic movements, and the uprising of right-wing activists that have proven to be forceful, even in well-established democracies. Historically, the link between education and democracy has been discussed for decades, formally stated in the Norwegian curriculum in 1939 (Koritzinsky, 2021). The current study focuses on how student teachers experience codetermination and participation as a part of democracy and citizenship in teacher education, along with how they plan to teach democracy and citizenship as teachers in schools. These students will enter the Norwegian school with a curriculum that was reformed in 2020, and the renewed curriculum has three overall interdisciplinary themes that run throughout all the disciplines: public health and life skills, democracy and citizenship, and sustainable development (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2017). The current study examines the following:

· How do student teachers perceive democratic education?

· What experiences do student teachers have with democratic education and participation in Norwegian teacher education?

· How do student teachers plan to practically implement their visions of teaching democratically as teachers in Norwegian schools?

In 2017, Norway reformed the teacher education program to a five-year master’s education (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2016a, 2016b), and extensive interviews with six of the first students to complete the new master’s program from two different universities in Norway showed that they chose not to be actively involved in shaping the practical, structural, and theoretical content of teacher education while demonstrating uncertainty regarding how to teach democratically in schools. There appears to be a discrepancy in how student teachers perceive democratic education and how they transfer these perceptions into action. Previous research has demonstrated that there is often a discrepancy between ‘theories of action’, which is values and perceptions, and ‘theories-in-use’, which is what we do (Argyris, 1995, p. 1).

First, the current article will display frameworks of perceptions on democratic education (Feu et al., 2017; Sant, 2019), demonstrating the diversity of understanding of education for democracy and citizenship. These frameworks illuminate how student teachers might have perceptions aligned with certain discourses while simultaneously demonstrating praxis or experiences within another. Further, through the lens of critical pedagogy, the present study critically examines the student teachers’ omission to participate and their lack of experienced agency in teacher education, along with how these experiences are mirrored in their planned teaching as teachers in schools. Because the focus stretches from the student teachers’ experiences in teacher education to their planned teaching in the future, it is necessary to comment on discourses and development in education from primary school to the university level. This is because the student teachers’ previous and current experiences are relevant in understanding both perceptions and praxis, along with the possible discrepancy between these.

Teaching democracy and citizenship is comprehensive. Such teaching should ideally empower students in the growth of self-determination and agency (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2017; Skaalvik et al., 2020), address power relations (Rönnlund & Rosvall, 2021), facilitate consciousness of social justice and critical engagement, and stimulate political literacy (Westheimer, 2015, 2020). In the framework for general competence in teacher education, the following is statutory:

[The graduate] can reinforce international and multicultural perspectives in the work of the school, contribute to gaining an understanding of the status of the Sami people as indigenous people, and encourage democratic participation and sustainable development (Ministry of Education and Research, 2016, p. 3).

This framework demonstrates and contextualizes democratic education in combination with a diverse society and multicultural perspectives, indicating a broad understanding of democracy, where it is statutory that student teachers should cultivate competencies for democratic participation. The student teachers’ experience with participation in their education is essential for their familiarity with teaching through democracy because teacher education and academic content teach them how to teach (Lindstøl, 2017). The importance of knowledge on how to facilitate an education that aims for students’ participation and agency is urgent (Säljö, 2012) because ‘fostering student engagement and voice within and through teacher education is a rare phenomenon’ (Cook-Sather, 2007, p. 346), and research on students’ experience and role as active contributors in teacher education is limited.

Why Freire and critical pedagogy are relevant to the context of Norway

Paulo Freire (1996) is often regarded as the founder of critical pedagogy. He was born in Brazil in 1921, and his critique is rooted in his own experiences as a poor student and as an educator with a specific interest in adult illiteracy (Smidt, 2014). His critique and tradition have been further developed by other educators rooted within a political tradition of Marxism. Because the perceptions and praxis for education are dependent on history and context, it is challenging to compare theoretical traditions with different roots than the ones inquired (Haugsbakk, 2013). However, it is necessary to focus on international discourse developments and its critique with supranational organizations becoming more influential (Befring, 2022; Haugsbakk, 2013) and with governments now monitoring progress in education through large-scale international tests such as the OECD[1] Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and Trends in International Mathematics and Science Studies (TIMMS) (National Center for Education Statistics, 2022; OECD, 2021; Säljö, 2012). PISA was introduced in Norwegian schools in 2000 and then repeated every third year, indicating the level of skills in mathematics and Norwegian among 15-year-old students in Norway. The PISA test revealed a decline in skills and competencies from 2000 to 2006. The low 2006 score is often referred to as ‘the PISA shock’ in Norway, leading to school reform in Norway in 2006[2] and annual national testing (Sanden, 2010). The renewed curriculum LK20, implemented in 2021, is a continuation of the 2006 reform (Sjøberg, 2022), demonstrating how supranational organizations such as the OECD influence Norwegian education.

Säljö (2012) argues that we need to focus on how children are enabled to participate in schools and the implications their involvement has for their future lives, not only focusing on whether they can repeat specific knowledge and use practiced competencies alone. Critical pedagogues are alarmed by the neoliberal tendencies in educational discourse and fear that the ambitions for education have drifted far from John Dewey’s principle of ‘[education as] a process of living and not a preparation for future living’ (Dewey, 1897, p. 7). To facilitate and strive for all citizens to be involved in society should be a guiding principle to sustain a viable democracy, one in which education plays an essential role (Dzur, 2017). Crises such as climate change, war, and the COVID-19 pandemic have demonstrated the importance of people’s engagement, along with the importance of enabling citizens to criticize and discuss to resolve conflicts and experience enabled to do so (Armeni & Lee, 2021; Carvalho, 2010; Chan et al., 2021).

Democratic education

Multiple means of categorizing democracy and democratic education have resulted in diverse sets of frameworks (Feu et al., 2017; Sant, 2019). These frameworks highlight the complexity of what democratic education is or should be. Through an extensive literature review, Sant (2019) demonstrates eight discourses of democratic education, while Feu et al. (2017) separate the different dimensions of democracy into governance, inhabitance, otherness, and ethos. Because the dimension of governance seems to be prevalent in a liberal understanding of democracy and in teaching democracy, a broader understanding of what democratic education could be is timely. Governance democracy describes the form and structures of a form of state governance, the inhabitance dimension entails the conditions which citizens inhabit, otherness acknowledges how recognition of each other is essential for peaceful dialogue and coexistence, and ethos is a way of being in the world, consisting of the values and virtues that allow for democracy at all levels to prevail (Feu et al., 2017).

I have combined Feu et al.’s (2017) four dimensions with Sant’s (2019) eights discourses in a table (see Table 1). Sant (2019) illustrates that democratic education can be perceived in eight differentiated ways, and Feu (2017) demonstrates how democratic education can be understood in depth through these four dimensions. I have placed a different name for the dimensions in brackets, where I have interpreted the content of the dimensions to be understood in educational settings.

Table 1. Eight discourses of democratic education

|

Dimension ↓ |

Elitist |

Neoliberal |

Liberal |

Deliberative |

Multiculturalist |

Participatory |

Critical |

Agonistic |

|

Educational main aspects |

Differentiating students’ education based on social role and future expectations. |

Students and their parents as consumers where schools are competing for students. |

Oriented on rationality based on equal and universal opportunities. |

Oriented on communication and plurality of opinions and seeking consensus. |

Devotion to culture and difference is democratic education. |

Action-centered education where student participation is essential. |

Deficits in society can be solved through the realization of the unjust social reality. |

Favor conflict and dialogue as the basic premises for democracy. |

|

Governance (Power relations) |

A competent small elite as power holders. |

The power to choose is in the hands of students and parents to decide school content and organization. |

Representativeness where students have equal rights and liberty to participate. |

Co-decision process where students, parents, and educators are all included. |

Rejects any normative perception that does not acknowledge plurality. |

Involvement of all where participation is regarded as acting as a responsible citizen. |

Identify hidden power structures and liberate oneself and society. |

Equality through perceiving all as equally intelligent with a possibility to be reasonable. |

|

Inhabitance (Resources) |

Accepting a socioeconomic hierarchy. |

Logics of the free market with competition for resources. |

Pluralism and freedom are essential. |

Schools and communities should facilitate the participation of all those involved. |

Learn language, culture, and religion, and have spaces for intercultural interaction. |

Schools and communities should facilitate the participation of all those involved. |

Education is also a fight for resources and the ability for all to social mobility. |

Creating an educational space welcoming dissent and emotional expressions. |

|

Otherness (Recognition) |

Not initiating egalitar-ianism. |

Recognition of individual freedom for all.

|

Recognition of individual freedom for all.

|

Recognition of ambition of consensus. |

Recognition for others is the core but does not presume consensus. |

Child-centered pedagogics that recognizes students’ abilities. |

Claim a truth of repression and do not recognize other perspectives. |

Recognizing the diversity of opinions is important for coexisting. |

|

Ethos (Democratic values) |

A knowledgeable elite will secure stability. |

Individual preferences and competition are regarded best pathways to personal freedom. |

Freedom, rationality, and equality are central values. |

Involvement and allowed plurality should be guaranteed. |

Diversity and plurality are superior to freedom. |

Democratic practices are a way of being in a world where acting is central. |

Solidarity through close interaction with communities to overcome injustice. |

Openness to disrupt the hegemonic order is a democratic way of life. |

The table is relevant for my analysis because it provides a language that differentiates the perspectives on democratic education while visualizing how education for democracy and citizenship is contested and perceived differently. Working within the field of democracy, it is essential to understand and recognize this diversity. First, recognition of different perspectives is democratic because we do not always experience democracy in education as the same thing, and disagreements and controversies could offer important discussions. Second, illustrating this diversity and then placing oneself within such a framework can help display political, ideological, and normative perceptions. Third, a broad understanding of different ways of understanding education for democracy contributes to identifying how discursive tendencies are connected to societal and political developments. Sant (2019) and Feu (2017) highlight the diversity and complexity of democratic education.

This article is theoretically placed within the participatory and critical discourse of democratic education and focuses on agency as an interpersonal psychological process that is developed and cultivated in the social space, where agency and self-determinization are regarded as essential democratic competencies. The studies theoretical perspective is based on stated regulations concerning democratic education, and critical pedagogy.

The UN states in the Convention of Children’s Rights Articles 12, 13, and 17 that the right of children’s freedom of speech, the right to express thoughts in matters regarding the child, the right to information, and the right of being consulted in decisions have implications for the child (United Nations, 1989). In addition, the Committee for the UN Convention on Children specifies the need for legislation regarding pupils’ representation and participation in decision processes in schools (UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2009). In the Committee’s general comments on Article 12, the following is specified:

States parties shall assure the right to be heard to every child “capable of forming his or her own views.” This phrase should not be seen as a limitation, but rather as an obligation for States parties to assess the capacity of the child to form an autonomous opinion to the greatest extent possible. This means that States parties cannot begin with the assumption that a child is incapable of expressing her or his views. On the contrary, States parties should presume that a child has the capacity to form her or his own views and recognize that she or he has the right to express them; it is not up to the child to first prove her or his capacity. (UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2009)

In the literary analysis of Article 12, the obligation is not only to allow freedom of speech but rather to state an obligation to promote the capability of the ‘autonomous opinion’ of the child (UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2009). Norwegian Educational Law 1-1 specifies, ‘They [pupils and apprentices] must have joint responsibility and the right to participate’ (Ministry of Education and Research, 1998). This paragraph entails that schools must facilitate pupils in experiencing responsibility and different ways of participating both in formal representation and in everyday work in the classroom (Nordrum et al., 2019). This paragraph is mirrored in the core curriculum and in the values and principles for primary and secondary education, where schools are imposed to ‘prepare them for participating in democratic processes. … The school shall stimulate the pupils to become active citizens and give them the competence to participate in developing democracy in Norway’ (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2017).

Previous research on the different understandings of democratic education in Norway has indicated that a liberal understanding is prevalent (Grønnestad, 2019; Marjavara, 2013; Mathé, 2016; Opphaug, 2022), with the democratic competitive political election system where direct participation is traded off for representation (Børhaug, 2008) and further defined as an individualistic and competitive-oriented approach to democracy (Bragdø & Mathé, 2021; Solhaug & Børhaug, 2012). Practical participatory approaches to cultivating and stimulating a democratic way of being in the world in a Deweyan tradition appear as something that has been traded off for learning about the political system (Boyte & Finders, 2016). In her study of Norwegian textbooks for upper secondary schools, Grønnestad (2019) finds that participation was mentioned in every book, though never as a component that has the potential for empowerment or self-development.

Research from Sweden indicates that student teachers connect their participation in education to their learning and future work (Bergmark & Westman, 2018), which does not seem to be the case in the current study. According to Bergmark and Westman (2018), the student teachers’ motivation for participation to benefit the university was absent in their context of Sweden, corresponding with the results from the present study.

A pedagogy based on agency

Agency is essential for democratic education because it entails self-determination, free will, and action aligned with autonomy. It is a basic human necessity to be oneself in the encounter with others, which is closely linked to participation and responsibility to be engaged for change, both for the collective and personal good (Bandura, 2018; Brown & Westaway, 2011). Agency entails a certain degree of individual autonomy in and through interaction with others. There is a division between the logic of individual agency in educational settings where agency is regarded as pure individuality, in which students’ main purpose is as laborers in a marketplace or individual agency as interconnectedness enabled to form social conditions (Destigter, 2014). This division does not necessarily exclude the other but is a signal of differing pedagogical perspectives on democratic education. The individual perspective is prominent in the elitist, neoliberal, and liberal discourses on democratic education, while the other five discourses regard individual agency as essential when it comes to the formation of social conditions.

Dewey (1897) draws a distinction between the psychological and social aspects of education, where the psychological is in constant interplay with the social. For Dewey, these mechanisms cannot be separated because mental capacities are shaped and adapted through involvement in social relations. To prepare young people for the future, it is essential ‘to give him [the child] command of himself’ (1897, p. 6) with abilities to use all of the child’s capabilities for acting according to one’s own best judgment, hence converting education into psychological terms. Capacity is a central element of agency and is the individual ability necessary to grow, learn, and act (Brown & Westaway, 2011): it consists of both psychological and social aspects. Capacity is moving away from the role of ‘powerless spectator’ and ‘coping actors’ and into the role of ‘adapting comanagers’ (Fabricius et al., 2007). Sen (1999) describes capacity as a person’s abilities and resources that enable them to form their own life. Acknowledging the importance of agency, both as a psychological and a social aspect of education, has been particularly highlighted by critical pedagogues. Stimulating students’ agency through education is, for critical pedagogues, closely connected to education for democracy, social change, and civic engagement (Freire, 1996; Giroux, 2014, 2020; hooks, 1994).

Critical pedagogy’s interconnectedness with societal change

In critical pedagogy, agency is an ethical, theoretical, methodological, and practical fundamental based on the idea that teaching does not fill students with knowledge but that students themselves must interpret what they are being taught to make sense of it (De Lissovoy, 2010; Freire, 1996; Giroux, 2020; hooks, 1994). Hence, students’ learning is dependent on their agency, and Bandura (2018) describes the core of human agency as metacognitive self-reflectiveness through one’s ability to evaluate themselves and their actions. Agency is an ethical stance in addition to a pedagogical base because students within the tradition of critical pedagogy should be perceived as independent and conscious (Freire, 1996; Giroux, 2020; hooks, 1994). Freire (1996, p. 61) criticizes what he describes as ‘banking education’, a pedagogical process where the educator imagines good education to be a mere transfer of knowledge where students are seen as passive recipients. Freire’s (1996) critique has been repeated by other pedagogical theorists (Befring, 2022; Giroux, 2021), highlighting an education closely linked to social change, where the educator should facilitate engagement for social awareness, here constructed on the premises of equality between educator and student (De Lissovoy, 2010). The interconnectedness of schools and society is highlighted in critical pedagogy, which defines schools as a mirror of society (Christie, 1971) that can impact and generate societal changes (Illich, 1971).

Biesta (2012, p. 585) urges for what he describes as a weakness of education, where the student’s subjectification through the advancement of a person’s qualities should be the aim of education, rather than endorsing a language that describes education as something fixed or strong, safe, and secure. Biesta’s (2012) description of subjectification resembles Freire’s (1996) concept of conscientization, which is a pedagogical process where an individual develops from an uninterested person who is accepting of the status quo into becoming someone who sees reality as it is and reacts to this process through praxis or engagement in change. Within the tradition of critical pedagogy, power relations are central, where capitalism is regarded as an extensive ideological power mechanism that is destructive to students, as they incorporate competition and hierarchical thinking, expecting subordination and domination (Giroux, 2021; Giroux, 2014). Critical pedagogues are highly critical of the elitist and neoliberal discourse, claiming that these discourses have adopted the free market ideology as their main objective, maintaining a power hierarchy created and upheld through competition and clearly stated roles. These structural limitations and expectations from schools in deciding what to be done and when, have limited students’ possibilities to develop autonomy within the school system (Skaalvik et al., 2020) and have been compared with prisons and slavery, where the pupils are at the bottom of the hierarchy, unpaid but forced to partake and be evaluated (Christie, 1971). Democratic education within the critical tradition is based on the notion that both the student and educators are seen as learners together (Freire, 1996), a symbiosis closely linked to society. ‘He [Freire] viewed capitalism as not only an economic system but also as a cultural and pedagogical system that stripped people of their agency, condemning them to an ideology in which they internalized their own oppression’ (Giroux, 2021, p. 3). To be freed from oppression, critical thinkers urge for an education where students see the structures of oppression that exist and can act on this oppression. In doing so, educators must move away from uninteresting classroom experiences toward an engaged pedagogy characterized by active participants in learning (hooks, 1994). In doing so, everyone in the classroom must be acknowledged as important to the learning process: ‘These contributions are resources … Excitement is generated through collective effort’ (hooks, 1994, p. 8) where students are involved in their learning process, here based on the perception that ‘to be voiceless is to be powerless’ (Giroux, 2020, p. 179).

Eberly (2002) argues that the current schooling system is built on the rhetoric of a corporate discourse in an individual-oriented matter. This may be why Giroux (2014, 2020) requests a philosophy of education for the public good instead of an individual right, stressing that education is far more than occupational training.

Methods

I have recorded 16 interviews with six student teachers in the process of writing their master’s thesis. Two of the student teachers were interviewed two times, and four of them were interviewed three times. Inspired by a democratic methodology, the students were chosen because of their overlapping interests in the interdisciplinary theme of democracy and citizenship. I hoped the interviews would benefit their research because the democratic approach carries the ambition to empower participants instead of just harvesting empirical data (Beebeejaun et al., 2013; Bell & Pahl, 2018). I recorded interviews with each of these six students from June 2021 to December 2021. The first interview was an introductory interview in which I wanted us to connect, both thematically and personally. The introductory interviews were nonstructured and based mostly on sharing our projects and discussing perceptions of how teacher education and schools practice the interdisciplinary theme of democracy and citizenship. The second interview was semi-structured, and the third interview was semi-structured, here based on the previous two. Close cooperation and connecting through several rounds of interviews altered the structure from interview to dialogue interviewing (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009), and I experienced the student teachers as interested in my project as well. This approach developed progressively, and the strategy inspired the different steps in the research process (Bengtsen & Munk, 2015). I have translated the excerpts from the interviews in this article from Norwegian to English, and in the process, I removed utterances such as ‘ehm’ and ‘hmm’ to present reader-friendly quotes.

Ambition for a democratic methodology

Several rounds of interviews with the same participant, here centered on the same thematic area, provided the opportunity to see whether the arguments and narratives were consistent over time. Repeated interviewing and talking also allowed us to connect on a personal level, which is an advantage when interviewing someone on sensitive subjects (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009; Toft et al., 2021). Because I wanted to investigate the student teachers’ own experiences with agency, participation, and the ability to dissent in and through their education, it was essential that the student teachers could talk openly. Although the interview developed into a dialogue interview, where we shared perceptions and experiences (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009), there could have been power asymmetry because I, as a researcher, had contacted the student teachers, asked for the interviews, defined the conversational content, and controlled the interpretation of the data (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009; Leavy, 2017). I had an ambition of a democratic methodology, with cooperation, analyzing, or even writing up together, but I experienced that the student teachers had busy schedules and seemed to desire independence regarding their master’s thesis. I realized that a democratic methodology might necessitate a common ambition and required planning together from the beginning.

Coding

The project was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) (Norwegian centre for research data, 2022), following the guidelines for research ethics in the social sciences and the humanities (NESH guidelines) (The Norwegian National Research Ethics Committees, 2021), and the participants signed consent forms before audio-recording the interviews. These interviews were transcribed verbatim, coded in vivo, and categorized thematically. Because the coding was in vivo, I ended up with over 1,000 codes. I coded all the statements I regarded substantial at the time to get an overview of the material and to be familiarized with the data. I categorized the codes into 34 categories based on the codes’ thematic content to investigate the commonalities and discrepancies in the material. The largest categories were ‘Democracy and citizenship education’ = 117 codes, ‘The important praxis/internship’ = 105 codes, and ‘Teacher-students codetermination/Teacher students’ participation’ = 95 codes. Although the codes and categories were empirically based, the initial questions in the interviews were rooted in theory and, hence, an abductive approach (Tjora, 2021). The data collection and analysis were aimed at investigating student teachers’ perceptions of education for democracy and citizenship, along with practical examples of how they experienced teacher education regarding teaching democratically. In the initial phase, I was particularly interested if they felt they were able to disagree (Rancière, 1991, 1999; Rancière, 2010), and the role of dissent in teacher education and their internship and planned teaching at schools. Their expressed lack of participation emerged as essential during the interviews, changing the project from agonistic (Mouffe, 1999; Rancière, 1991, 1999; Rancière, 2010) to participatory (Biesta, 2012, 2014, 2020; Biesta & Lawy, 2006; Biesta et al., 2017; Biesta, 2011; Dewey, 1897, 1897/2000) and a critical theoretical focus (Freire, 1996; Giroux, 2021; Giroux, 1988; hooks, 1994).

The discrepancy between how the student teachers saw participation as important but did not act on it was visualized when studying the codes. Seeing these categories together with ‘Pupil’s participation/pupils’ codetermination’ = 113 codes illuminated the similarities with how the student teachers experienced codetermination, along with how they planned on including pupils in codetermining in schools. This was particularly interesting when investigating the category of ‘Democracy and citizenship education’, where the student teachers underlined the importance of participation in teaching democratically.

Ethical considerations

The current study is based on a small number of participants and illuminates a snapshot of a limited number of student’s experiences. The student’s area of interest overlaps with this project, hence not including student teachers with other experiences from different subjects of teacher education. This close cooperation could have led the students to elaborate in our interviews when and if noticing that I was intrigued or less interested. Instead of striving for objectivity, I responded genuinely in and through our interviews but was conscious not to correct their perceptions. This approach was necessary because my philosophical and ethical stance on the methodology was sharing, not harvesting. Therefore, the implications of my effect on the participants are necessary to bear in mind.

Participants

The six student teachers I interviewed came from two different universities in Norway. They have been anonymized and given pseudonyms. The participant table below is an overview of the student teachers interviewed, affiliation, and the number of recorded interviews with each of these student teachers (see Table 2).

Table 2. An overview of student teachers interviewed

|

Student teacher: |

Affiliation: |

The number of recorded interviews with the student teacher: |

|

Thomas |

University 1 |

3 |

|

Asif |

University 1 |

2 |

|

Elisabeth |

University 1 |

3 |

|

Thea |

University 2 |

2 |

|

Sarah |

University 2 |

3 |

|

Marcus |

University 2 |

3 |

The discrepancy between perceptions and praxis on democratic education among student teachers

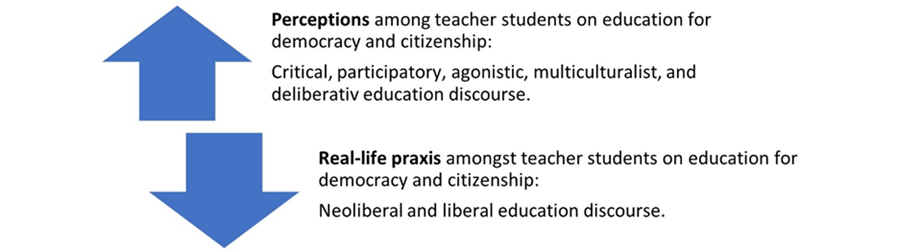

The results from the current study illuminate two important aspects where one presumably influences the other. The first main result is that the student teacher feels that the ability to participate and act in and through their education is present, but they choose not to take advantage of this possibility. They see a close connection between participation and teaching democratically but do not seem to assign the same importance to their involvement in education. The second main result is on how they plan their future teaching on democracy and citizenship in schools, which exemplifies how they plan to facilitate pupils’ autonomy and self-determination in schools. The student teachers explained how they will be facilitating pupils’ co-determinization as future teachers in schools in situations where the outcome of the pupils’ decisions does not matter much. They indicated that pupils’ preferences should be limited within the frames of the pedagogical intentions and not change or alter the planned teaching. The interviews revealed a discrepancy between the students’ perceptions of education for democracy and real-life praxis, both as students in teacher education and in their planned teaching as educators themselves (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. A discrepancy between student teachers' perceptions and praxis

The student teachers explained how they would rely on elected student representatives to initiate critiques or suggestions to the university and place themselves on the sideline regarding such involvement. In addition, the student teachers explained how they would facilitate mock elections in the future when practicing democratic praxis in the classroom. Describing a democratic praxis as elected representatives and elections indicates a neoliberal or liberal exercise of education for democracy (Sant, 2019). When discussing democratic education more generally, the student teachers noted participation and the ability to disagree as important aspects of learning democratic coexistence. Marcus highlighted how a multicultural classroom facilitates and provides opportunities for practicing democracy, indicating a multicultural perception (Osler & Starkey, 2010; Sant, 2019).

Agency in teacher education

Høgheim and Jenssens (2022) report that student teachers experience that their frustrations with teacher education are not considered because they feel a lack of impact and openness from universities. Some of the student teachers in the current study reported the same because they experienced limited space for being involved in teacher education.

Interviewer: What experiences do you have with participating in teacher training?

Marcus: No, little.

Interviewer: On both subjects, content, and methods?

Marcus: Yes, and I would think that the teachers have guidelines to follow in a way, but it is sort of like when I show up for class, the plan for the day is set, right? And we are not allowed to take part in deciding: they have a plan, and it is carried out. It is still the case that if they have planned for it to be an hour of lunch is not, so we think it’s a bit long, so then we have to decide that it should be half an hour instead or if we want to shorten the breaks a bit to go home a little earlier: they listen to such things, but not like the content and the method and stuff like that. There has been very little of it.

Previous research from the Icelandic context has indicated that students in upper secondary school would rather try to influence how pedagogical practices were carried out in the classroom than the content, such as curriculum and what they would learn (Bjarnadóttir et al., 2019). Marcus expressed how the student teachers were not invited to have an opinion on the educational content of teacher education but could be included in organizational aspects such as the length of their lunch break. This was also expressed by Thea in the quote below, where she expressed that ‘what is important [the syllabus] they have decided in advance’, taking for granted how the content is predetermined by educators.

Interviewer: Yes, do you feel that you can participate, then, in teacher training? Do you feel that you can influence or express your opinions about what education should be like?

Thea: I may not have been the one who is the most engaged, but I would say that if I wanted to, I could have influenced teacher training.

Interviewer: Do you feel that you are being listened to?

Thea: Yes, I feel that …

Interviewer: Are there any subjects or teachers or situations during your course of study in the teacher training program where you experience participation?

Thea: Yes, I think so. I think it varies from teacher to teacher. Some teachers are very open to us being able to decide a little bit, at least, how we are going to go through things. What is important, they have decided in advance with the syllabus and such, of course. But there are, yes, some teachers who are very open to it. There is talk of feedback after each lecture, then, and the teacher chooses to do something different the next time. Then other teachers are more decisive on, ‘it is my teaching that counts’. And then there is the difference in subjects as well. In social science, I think they have been quite open. CREE[3] (Christian and other religious and ethical education) may be a little less open, as I have experienced, at least.

The student teachers reported that they did have the ability to impact but chose not to use this opportunity. Thea described evaluation after a course in teacher education as participation, though realizing that changes from such evaluation will not always benefit themselves because they have already completed the course. The student teachers reported that they could address problematic issues if they occurred in teacher education, and some of them have no problems addressing things they experienced as a problem, while others reported that they did not feel comfortable bringing forward complaints.

In talks on agency, the student teachers automatically connected participation with the ability to address the negative aspects of teacher education, leaving the more positive aspects by the wayside. A common feature among the students was that they connected raising their voices with addressing problematic issues, thus regarding involvement as complaining. They chose not to be involved because they either did not see themselves as troublemakers, did not assign a leading role to themselves, or considered other students to be better suited.

Interviewer: Do you experience that you can participate in your study program? Do you experience participation there?

Asif: Yes, I feel that we can do so. We have student contacts, and we know where we can go if we want to report something. We have someone in the class who is, if there is something wrong, they go straight to the point that ‘we have to do this like that’, so I feel that we have them in the class, and then we have the others who are like that ok, they can take the job, because they pay attention, so they know everything. So, I experience that we can report on things. That’s good. But I do not know if things change very quickly.

The student teachers reported that they experienced teacher educators listening to them and that the possibility for participation was present, but they described omission from management and teacher educators in responding to such input. In addition to assigning a leading role of involvement to other ‘more suited’ students in teacher education, some of the student teachers saw themselves as inadequate to participate because of their lack of knowledge of theoretical or structural aspects of teacher education.

Sarah: No, I might disagree on things, but I might be wrong … I have no previous experience with the university. I am like that I do not express my thoughts on things that are unfamiliar to me.

The student teachers reported that the thought of codetermination and participation in teacher education had not even occurred to some of them.

Interviewer: Do you miss participation in teacher training?

Elisabeth: No, well, no, I have not missed it; the thought has not struck me.

On the other hand, they reported that they could be included in theoretical discussions in classes.

Interviewer: Why do you think it is ok for you to speak your mind in professional discussions [in teacher education] and not on how things are organized and things like that?

Elisabeth: It is kind of not my business. I do not like to start something, to create a bad atmosphere, or something. I know there have been some disagreements with some other students, but I am not a person who says things like that, but I participate if there are professional discussions.

I asked Elisabeth how she would respond if she disagreed with how her study was organized, with the theory, or with one of the teacher educators, and she replied, ‘I would not have said anything’. One of the student teachers, Sarah, explained why she did not bother to engage that much in and through her education with a quote that might seem like laziness: ‘As long as the grades are ok, there is no need to make a fuss’, indicating that she prioritized just ‘getting through’. In addition, the student teachers often referred to schools and education as preparation for society, not a part of society itself.

Relationship with educator

The student teachers often referred to having a good relationship between the educator and learner as essential for an open classroom climate. They described the connection between themselves as teachers and pupils in schools as decisive for cultivating the pupil’s learning, motivation, and participation. Not all of them regarded this relational aspect as particularly important in their education, but those who had a relational experience with a teacher educator frequently returned to this teacher when exemplifying ‘good’ didactical modeling. For the most part, the student teachers were frustrated with one-way communication in classes, uninspired teaching, and nonexistent relationships with educators.

Interviewer: Because you said that someone teaches straight from PowerPoint, but then some manage to build the relationship. Is it important to you that you have a good relationship with those who teach in teacher education?

Thomas: Definitely, some transmit a sensation that they would like to get you involved, that see and realize that this topic is—or this subject is—maybe a little heavy. Good educators manage to alter it, ‘we must do this and that with the teaching plan’, and maybe even include our life events. They make it very personal, and they invite us in, not only to the skills they have, but also to their personal lives and how they experienced things. I find that very inviting ….

Interviewer: But what is your definition of a good relationship with a teacher educator?

Thomas: Two-way communication. You must have some social antennae to sense the room, to set up a scheme that is not monotonous. I feel that there has been a lot of banking education, if I may say so, that it is just communication one way, and maybe open to a question, but that is not what we need. We think more about how we can contribute to an activity. It is quite clear that if we are to sit for four hours and someone is reading from a PowerPoint, then yes, we could have done something completely different. To establish relationships is to invite us to a vulnerable space, I may say.

Thomas refers to banking education, a concept developed by Freire (1996) in describing a perception of education as a mere transfer of knowledge from the ‘knowledgeable’ to the ‘ignorant’. This model of teaching was criticized several times by most of these students, often explained by the fact that many teacher educators have no practical experience in teaching in schools and, therefore, were unable to use practical narratives of exemplifying theoretical perspectives. The student teachers also mentioned class size as important for whether they chose to be involved in classes. Most of the student teachers were less comfortable in larger compared with smaller groups in teaching.

Visualizing how to teach democracy and citizenship

The student teachers acknowledged the importance of pupils’ participation and agency in schools and underlined young people’s involvement in and through their schooling as essential in democratic education.

Interviewer: What is important to emphasize—to cultivate or stimulate, if you should have a democratic education?

Elisabeth: Yes, I think the participatory, oral skills, and being able to take or that one should be able to speak one’s mind, that students feel that they are heard and that what they say is heard. It will, in a way, maybe lead them in becoming more confident in themselves. I think that is very important.

The student teachers mentioned participation as important for motivation, both for themselves as students and for pupils in schools. But in practical examples, the student teacher did not pinpoint the importance of their participation or the participation of pupils in schools. Some of the student teachers stated that they did not experience much response from management and teacher educators to their complaints, and if considered, this would improve their motivation for being involved. One student teacher mentioned the ownership of their master’s thesis as important for motivation and the joy of learning.

In sharing perceptions of how to teach democratically in the future, the student teachers underlined the importance of codetermination and participation. When asked about practical methods of implementing codetermination, they often exemplified situations in the classroom where the pupil’s codetermination did not matter, even though they defined democratic education as a pedagogical approach where pupils should influence its content.

Interviewer: How do you think democratic teaching can be in the classroom?

Sarah: Yes, I think it is important to practice it. Allow students to participate and decide. And that applies to both indirect and direct democracy. It can be simple things … And let the students influence their everyday lives and things that you [as a teacher] see as completely insignificant. If it is a question of working on a project, and the question is, do you want to have recess before, in the middle or do you want to quit five minutes earlier? Then, there is one thing that is completely irrelevant to me as a teacher because there is so much activity in the classroom that it does not disturb if we take a break. And I think it is important to bring in things like that; it does not have to be big. It does not have to be that big and spectacular.

There also seemed to be an understanding that younger children should be provided fewer opportunities to impact education than adolescence because they are ‘less capable’.

Interviews: You said the pupils can decide things that are not so important, but should they also be allowed to decide things of greater importance?

Sarah: Maybe not in primary school. I do not think they can fully understand the consequences. No, I do not think so. No, not so early. In upper secondary school, I think maybe they can be involved and influence more, at least in tenth grade, because then they are more reasonable. Then, they can understand the consequences. While in primary school, it has not been fully developed. Not that it has been fully developed in upper secondary school, either, but to a much greater extent.

----------------------------------------

Interviews: Do pupils’ participation have any limitations?

Marcus: Yes, it has its limitations, because you have the curriculum that you must deal with, at least for tenth grade, I think it is difficult, because the students should have certain assessments according to certain criteria, so you must take advantage of it [participation] at the beginning of secondary school and the intermediate level.

Interviews: Do you think we can start with the first grade when they start school? Is this possible?

Marcus: Yes, I think, but when they are that small, you must not let them have too many choices because then I think the students become insecure. But they can choose between two things, for example.

In the above excerpts, Sarah expressed that tenth-grade students should be more involved in their education than smaller children. Marcus expressed that grading, because tenth-grade pupils in Norway are graduates, is a hindrance for involving them, hence expressing assessment as the primary effort at this level. Marcus, like Sarah, saw smaller children as less capable of participation, and their involvement should be limited by, for instance, only giving them two choices to make sure they do not become insecure. The student teachers communicated that participation and agency are competencies that should be cultivated through schooling but seemed critical of just letting pupils do as they please.

Interviews: Overview before you start and then set the framework and give room to participate within it?

Thomas: Yes, if you let the students participate all the way and have no structure on it, the students may think that ‘yes, now I can just do as I want’. So having this framework is very important. And of course, be open to learning from each other, but in the end, it is you [as a teacher] who decides the framework.

Thomas expressed a perception that regulation for participation is necessary and that limitations seem easier to explain than possibilities.

Discussing perceptions and praxis for democratic education

It is interesting how the student teachers reported that they did not seem to experience—or desire to participate—in their education, while at the same time acknowledging the importance of active involvement throughout all levels of education. The student teachers did not comment on their participation as important in the process of learning (intrinsic motivation), in preparing themselves for a future profession as teachers (altruistic motivation), or as a way to benefit the university (extrinsic motivation) (Bergmark & Westman, 2018), as illustrated by the quote from Sara, ‘As long as the grades are ok, there is no need to make a fuss’. Sarah mentioned grades as important, and the quote was a part of an interview discussing why she abstained from being actively involved in and through her education. Highlighting grades makes it appear that the formalization of occupational training is the main objective. The student teachers’ approach to education was often referred to as mere preparation for future work, where society is seen as out there and the preparation is in the university, which might strengthen the vision of the university as a closed-off entity disconnected from society. This illustrates an approach to education to reach a goal with as good results as possible and then be done with it. Such a perspective on education could impede the will to engage because it is seen as an individualistic hindrance.

Learners as disconnected from the world

Schools are also referred to as preparation for society ‘out there’. The student teachers discussed their education as preparation for society and work in schools, while pupils in schools are prepared for society and work out there. In so doing, learning and being the one who learns is regarded as a closed space disconnected from the world, both as students in universities and pupils in schools, which can be a result of an individualistic goal-oriented discourse. Biesta (2012) urges for an education that puts weight on subjectification, linked to ‘action’ and ‘being in the world’ (Biesta, 2012, p. 589), highlighting the process of education instead of the finalized results. Previous research has demonstrated that the liberal perception of democratic education is prevalent in Norway (Grønnestad, 2019; Marjavara, 2013; Mathé, 2016; Opphaug, 2022), permeated with individualistic and competitive values. In an individualistic society, the sense of obligation toward the collective could be fading, where the primary goal becomes one’s own advancement. The competitive, individualistic, and result-oriented discourse that may have embossed education is a problem (Klafki, 2011, p. 274), especially if this creates an image of education as obediently following orders and keeping your voice to yourself rather than being engaged and emancipated.

In the part of our interview discussing how to be involved, the student teachers often referred to participation as complaining, not referring to positive ways of being engaged and involved. A self-reflectiveness on the importance of their agency seemed absent (Bandura, 2018), as illustrated by Asif’s quote on how other students were more suited to influence teacher education, or as commented by Sarah, who did not feel comfortable engaging because of unfamiliarity with the structures of the university. It seems they experienced a lack in their capacities necessary to be involved (Sen, 1999), reducing their opportunities for subjectification or conscientization, here in not taking the role of conscious, knowledgeable agents who can take action (Biesta, 2012; Freire, 1996).

A utopian way of teaching in the future

Sarah and the other student teachers’ perspectives on democratic education as to ‘[g]ive students the opportunity to participate and decide’ seemed absent regarding their education and appeared only as a utopian way of educating in the future. One reason could be a lack of experience in positive involvement. Another reason could be that the interviews also centered on the student teachers’ ability to dissent in and through their education. It is still interesting and relevant because they had few practical experiences of being included in a non-valuative way in teacher education. The student teachers seemed trapped in a pattern where they accommodated the position as passive objects when in the role of learners. One of the student teachers, Thomas, expressed his opinion on why they avoided their involvement:

Thomas: I think many of my fellow students did not experience agency or the ability to participate in primary, secondary, or upper secondary school, and based on that, they are not able to handle very well when placed in a situation like that.

The student teachers’ agency in teacher education is like an illusion because of the hindrances experienced by the students themselves, and they seem to have transferred this same illusion of real agency to their visions of how to teach in the future The students have not experienced or expected to participate in the University, and their unwillingness to do so makes it appears to be the student’s choice not to be actively involved. Their approach to education could be based on expectations of what education is supposed to be like as they fulfil their role as students in a system they are socialized into through many years of schooling (Skaalvik et al., 2020). If previously unfamiliar with involvement and participation, it can be difficult to take on a new role, especially if the structures of the university are not open to or expect such behavior.

To critical pedagogues such as Freire (1996), students themselves must interpret what they are taught to make sense of, which depends on a method where the educator uses the students’ own experiences as a base for further inquiries. This approach requires involvement, and hooks (1994) urges facilitating joyful engagement, where everyone partakes (Giroux, 2020). Marcus pointed to his experiences in teacher education as follows: ‘when I show up for class, the plan for the day is set, right’, illustrating how the student teachers see their role and the role of the educator through this expectation of students as passive recipients of education. Critical pedagogues have repeatedly pointed at power relations as essential, paralleling the structures of power in society and education today to capitalism and neoliberalism while arguing that the corporate world of hierarchy and competition has infused educational discourse, where students internalize their oppression by incarnating the role as objects or consumers (Freire, 1996; Giroux, 2020; hooks, 1994). Critical pedagogy highlights how a neoliberal discourse immerses education, suggesting that only by acknowledging these hidden structures are students liberated and can act for the individual and collective good (Freire, 1996; Giroux, 2021; hooks, 1994).

Limiting pupils’ participation

These roles of objects-recipients-learner and subjects-providers-educator are visible in how the student teachers discuss participation. On a theoretical level, when explaining democratic education, the student teachers encompass pupils’ co-decision making. However, in practical examples, when explaining how to facilitate pupils’ democratic education in future teaching, real co-decisions are absent and only exemplified in situations where the pupils’ decisions do not matter much, for instance, as a recess before or after a session. The student teachers had different opinions on when the pupils were mature enough or had enough time to be included in educational decision-making, even though the right to participate is a stated regulation (Ministry of Education and Research, 1998) and should not be restricted to whether the pupil is regarded as capable (UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2009). Sarah expressed that pupils in primary school are too immature to understand the consequences of their choices and should be less included than pupils in secondary or upper secondary school. Marcus, on the other hand, felt that students in tenth grade had a stricter schedule because they are graduating, so they had less time for participation because of ‘certain assessments according to certain criteria’. The student teachers’ perceptions of when and how to facilitate pupils’ participation in decision processes in schools were not unanimous, and the student teachers seemed to explain practical limitations to a larger extent than practical possibilities for pupils’ participation. Freire (1996) urges for an education where the hindrances to a human agency can be visualized, and this process of becoming aware or ‘conscientization’ was seen as more important than getting knowledge and being evaluated in education. Working with students to build awareness for change and empowering their role as active citizens through the cooperation of learners and educators is essential in critical thinking. The student teachers’ limitations of pupils’ involvement might reflect traditional teaching in schools and a lack of experience with practical methods of participation.

In the laws and regulations for schools and teacher education, student agency and involvement are regarded as essential and specified, not as a normative value but as a stated regulation (UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2009; Ministry of Education and Research, 1998; Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2017). This could be one explanation of why there exists a discrepancy between the student teacher’s perception and praxis on democratic education. The perceptions could reflect stated laws and aims for education, while praxis could reflect the experience and traditional ways of teaching.

Conclusion

The student teachers in the current study seemed to perceive democratic education as participation and critical thinking through, for instance, the benefits of a multicultural context in the classroom. They highlighted ownership of tasks as essential for agency, motivation, and the development of democratic competencies, and they were negative when it came to pedagogical praxis resembling banking education (Freire, 1996). Their perceptions align with critical, participatory, multiculturalist, and deliberative democratic educational discourse (Sant, 2019). They expressed a lack of experience with participation in teacher education, explaining that teacher education does not facilitate their involvement, but at the same time, they expressed that they did not want or expect such participation. Although they had perceptions of the importance of pupils’ involvement and ability to co-decide, they had very few examples of how to include pupils, even though they were aware of the limitations of such involvement. They described the role of learners as consumers of education, an approach placed within a neoliberal discourse (Sant, 2019), demonstrating a discrepancy between their opinions and what they do.

The present study points to this discrepancy, but more research is necessary to explain why this discrepancy occurs and how teacher education and schools can experiment to develop an education that is aligned with real participation with the ambition to capacitate student and pupils’ agency.

A pluralist society needs cooperation, negotiation, and engaged citizens. These are essential competencies for citizens living together and constantly resolving obstacles at different levels in life. Narrowing democratic education to the mere transfer of knowledge about the elective system is, according to critical pedagogues, a distortion of an exciting opportunity to empower students and challenge social hierarchies. By combining democracy and citizenship in Norway’s renewed curriculum, the potential for a broader understanding is present. Critical pedagogy highlights how the discourse of competition and individualism might have influenced education while describing how education can be different and better, both for the individual student and the collective good. If society is immersed in a neoliberal, competitive, and individualistic way and education is a mirror of society (Christie, 1971), it can be almost impossible to reform the school without reforming society. Freire (1996) is aware of the power of context in education, and his vision for education stretches beyond the classroom.

References

Argyris, C. (1995). Action science and organizational learning. Journal of managerial psychology, 10(6), 20-26. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683949510093849

Armeni, C., & Lee, M. (2021). Participation in a time of climate crisis. Journal of law and society, 48(4), 549-572. https://doi.org/10.1111/jols.12320

Bandura, A. (2018). Toward a psychology of human agency: Pathways and reflections. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(2), 130-136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617699280

Beebeejaun, Y., Durose, C., Rees, J., Richardson, J., & Richardson, L. (2013). 'Beyond text': Exploring ethos and method in co-producing research with communities. Community Development Journal, 49(1), 37-53. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bst008

Befring, E. (2022). Skolen under lupen: problematiske trekk og løfterike muligheter. In E. Schaanning & W. Aagre (Eds.), Skolens mening : femti år etter Nils Christies Hvis skolen ikke fantes. Universitetsforlaget.

Bell, D. M., & Pahl, K. (2018). Co-production: Towards a utopian approach. International journal of social research methodology, 21(1), 105-117. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2017.1348581

Bengtsen, S. S. E., & Munk, K. P. (2015). Metoden, der sprænger sig selv. In J. E. Møller, S. S. E. Bengtsen, & K. P. Munk (Eds.), Metodefetichisme. Kvalitativ metode på afveje (pp. 41-65). Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

Bergmark, U., & Westman, S. (2018). Student participation within teacher education: Emphasising democratic values, engagement and learning for a future profession. Higher Education Research and Development, 37(7), 1352-1365. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1484708

Biesta, G. (2012). Philosophy of education for the public good: Five challenges and an agenda. Educational philosophy and theory, 44(6), 581-593. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2011.00783.x

Biesta, G. (2014). The beautiful risk of education. Paradigm Publisher. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315635866

Biesta, G. (2020). Risking ourselves in education: Qualification, socialization, and subjectification revisited. Educational Theory, 70(1), 89-104. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12411

Biesta, G., & Lawy, R. (2006). From teaching citizenship to learning democracy: Overcoming individualism in research, policy and practice. Cambridge journal of education, 36(1), 63-79. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640500490981

Biesta, G., Priestley, M., & Robinson, S. (2017). Talking about education: Exploring the significance of teachers' talk for teacher agency. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 49(1), 38-54. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2016.1205143

Biesta, G. J. J. (2011). Learning democracy in school and society: education, lifelong learning, and the politics of citizenship. Sense Publishers.

Bjarnadóttir, V. S., Öhrn, E., & Johansson, M. (2019). Pedagogic practices in a deregulated upper secondary school: Students’ attempts to influence their teaching. European educational research journal EERJ, 18(6), 724-742. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904119872654

Boyte, H. C., & Finders, M. J. (2016). “A liberation of powers”: Agency and education for democracy. Educational Theory, 66(1-2), 127-145. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12158

Bragdø, M. B., & Mathé, N. E. H. (2021). Ungdomsskoleelevers demokratiske deltagelse. Bedre Skole, 1 (2021). https://utdanningsforskning.no/artikler/2021/ungdomsskoleelevers-demokratiske-deltagelse/

Brown, K., & Westaway, E. (2011). Agency, capacity, and resilience to environmental change: Lessons from human development, well-being, and disasters. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 36(1), 321-342. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-052610-092905

Børhaug, K. (2008). Educating voters: Political education in Norwegian upper-secondary schools. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 40(5), 579-600. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220270701774765

Carvalho, A. (2010). Media(ted)discourses and climate change: A focus on political subjectivity and (dis)engagement. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Climate Change, 1(2), 172-179. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.13

Chan, E. Y. Y., Gobat, N., Dubois, C., Bedson, J., & de Almeida, J. R. (2021). Bottom-up citizen engagement for health emergency and disaster risk management: Directions since COVID-19. Lancet, 398(10296), 194-196. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01233-2

Christie, N. (1971). Hvis skolen ikke fantes. Universitetsforlaget.

Cook-Sather, A. (2007). What would happen if we treated students as those with opinions that matter? The benefits to principals and teachers of supporting youth engagement in school. NASSP Bulletin, 91(4), 343-362. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192636507309872

De Lissovoy, N. (2010). Rethinking education and emancipation: Being, teaching, and power. Harvard Educational Review, 80(2), 203-220,288. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/rethinking-education-emancipation-being-teaching/docview/578359730/se-2?accountid=43239

Destigter, T. (2014). In Good Company. Jane Addam's Democratic Experimentalism. In D. Schaafsma (Ed.), Jane Addams in the classroom. University of Illinois Press.

Dewey, J. (1897). My pedagogic creed. School Journal, 54, 77-80.

Dewey, J. (1897/2000). Utdanningens underliggende etiske prinsipper [Ethical Principles Underlying Education]. In S. Vaage (Ed.), Utdanning til demokrati. Barnet, skolen og den nye pedagogikk (pp.133-163). Abstrakt Forlag.

Dzur, A. W. (2017). Rebuilding public institutions together: Professionals and citizens in a participatory democracy. Cornell University Press.

Eberly, R. A. (2002). Rhetoric and the anti-logos doughball: Teaching deliberating bodies the practices of participatory democracy. Rhetoric & public affairs, 5(2), 287-300. https://doi.org/10.1353/rap.2002.0027

Fabricius, C., Folke, C., Cundill, G., & Schultz, L. (2007). Powerless spectators, coping actors, and adaptive co-managers: A synthesis of the role of communities in ecosystem management. Ecology and society, 12(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-02072-120129

Feu, J., Serra, C., Canimas, J., Làzaro, L., & Simó-Gil, N. (2017). Democracy and education: A theoretical proposal for the analysis of democratic practices in schools. Studies in philosophy and education, 36(6), 647-661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-017-9570-7

Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. B. Ramos, Trans.; 20th anniversary ed.). Penguin books.

Giroux, H.A. (2021). Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of Hope in Dark Times. In P. Freire (R.R. Barr,Trans.), Pedagogy of Hope: Reliving Pedagogy of the Oppressed (pp. 1-14). Bloomsbury Academic. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350190238.0004

Giroux, H. A. (1988). Teachers as intellectuals: Toward a critical pedagogy of learning. Bergin & Garvey.

Giroux, H. A. (2014). Neoliberalism's war on higher education (2nd ed.). Haymarket books.

Giroux, H. A. (2020). On Critical Pedagogy (2nd ed.). Bloomsbury Academic.

Grønnestad, I. (2019). Demokratiet i lærebøkene - En analyse av demokratiforståelsen som formidles i seks lærebøker for fellesfaget samfunnsfag på videregående. NTNU. https://ntnuopen.ntnu.no/ntnu-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2626891/Gr%c3%b8nnestad%2c%20Ingrid.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Haugsbakk, G. (2013). From Sputnik to PISA Shock - New technology and educational reform in Norway and Sweden. Education Inquiry, 4(4), 607. https://doi.org/10.3402/edui.v4i4.23222

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress. Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

Høgheim, S., & Jenssen, E. S. (2022). Femårig grunnskolelærerutdanning – slik studentene beskriver den. Uniped, 45(1), 5-15. https://doi.org/10.18261/uniped.45.1.2

Illich, I. (1971). Deschooling society. Calder & Boyars LTD.

Klafki, W. (2011). Dannelsesteori og didaktik: nye studier (B. Christensen, Trans.; 3. udg. ed., Vol. 14). Klim.

Koritzinsky, T. (2021). Tverrfaglig dybdelæring: om og for demokrati og medborgerskap - bærekraftig utvikling - folkehelse og livsmestring. Universitetsforlaget.

Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). Interviews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (2nd ed.). Sage.

Leavy, P. (2017). Research design: Quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, arts-based, and community-based participatory research approaches. Guilford Publications.

Lindstøl, F. (2017). Mellom risiko og kontroll - en studie av eksplisitte modelleringsformer i norsk grunnskolelærerutdanning. Nordisk tidsskrift for pedagogikk & kritikk, 3. https://doi.org/10.23865/ntpk.v3.734

Marjavara, G. B. (2013). "Ungdomsskoleelevers demokratiforståelse" - Den skjulte demokratiforståelsen. NTNU.

Mathé, N. E. H. (2016). Students' understanding of the concept of democracy and implications for teacher education in social studies. Acta didactica Norge, 10(2), 271-289.

Ministry of Education and Research. (1998). Act relating to primary and secondary education and training (the Education Act). https://lovdata.no/dokument/NLE/lov/1998-07-17-61

Ministry of Education and Research. (2016). Regulations relating to the framework plan for primary and lower secondary teacher education for years 5–10. regjeringen.no: Regjeringen. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/c454dbe313c1438b9a965e84cec47364/forskrift-om-rammeplan-for-grunnskolelarerutdanning-for-trinn-5-10---engelsk-oversettelse.pdf

Mouffe, C. (1999). Deliberative democracy or agonistic pluralism? Social Research, 66(3), 745-758.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2022). Trends in international mathematics and science study (TIMSS). https://nces.ed.gov/timss/

Nordrum, J. C. F., Fimreite, A. L., Hauge, A., Holmboe, M., Juvik, K. T., Krogsæter, Å., Mausethagen, S., Moen, K., Paulsen, J. M., Sætre, I. R., Børnes, C., Dahl, G. H., Eide, E. H., Grønli, M. E., Heggelund, M., Myhren, M. B., Rongved, G. L., & Sollie, S. (2019). NOU, Ny opplæringslov. Regjeringen: Regjeringen. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/0147d443bffd49f9971f54bfc26b5972/nou-2019.pdf

Norwegian centre for research data. (2022). About NSD - Norwegian centre for research data. https://www.nsd.no/en/about-nsd-norwegian-centre-for-research-data

Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. (2016a). Forskrift om rammeplan for grunnskolelærerutdanning for trinn 1–7 (LOV-2005-04-01-15-§3-2). https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2016-06-07-860?q=forskrift%20grunnskolel%C3%A6rerutdanning

Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. (2016b). Forskrift om rammeplan for grunnskolelærerutdanning for trinn 5–10. (LOV-2005-04-01-15-§3-2). https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2016-06-07-861?q=forskrift%20grunnskolel%C3%A6rerutdanning

Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. (2017). Core curriculum - values and principles for primary and secondary education. Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. https://www.udir.no/lk20/overordnet-del/?lang=eng

OECD. (2021). PISA Programme for international student assessment. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/

Opphaug, H. (2022). Democracy and citizenship in textbooks published after the National Curriculum 2020. Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences.

Osler, A., & Starkey, H. (2010). Teachers and human rights education. Trentham books.

Rancière, J. (1991). The Ignorant schoolmaster. Five lessons in intellectual emancipation [Le Maître ignorant] (K. Ross, Trans.). Standford University Press.

Rancière, J. (1999). Disagreement. Politics and philosophy. [La Mésentente: Politique et philosophie] (J. Rose, Trans.). University of Minnesota Press.

Rancière, J. (2010). Dissensus: on Politics and Aesthetics. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Rönnlund, M., & Rosvall, P-Å. (2021). Vocational students' experiences of power relations during periods of workplace learning - a means for citizenship learning. Journal of education and work, 34(4), 558-571. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2021.1946493

Sanden, C. H. (2010). -PISA-testen ble et sjokk for Norge. NRK, News article. https://www.nrk.no/norge/--pisa-ble-et-sjokk-for-norge-1.7413860

Sant, E. (2019). Democratic education: A theoretical Review (2006–2017). Review of educational research, 89(5), 655-696. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319862493

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. OUP.

Sjøberg, S. (2022). Da skolen gikk ad PISA. In E. Schaanning & W. Aagre (Eds.), Skolens mening: femti år etter Nils Christies Hvis skolen ikke fantes (pp. 131-153). Universitetsforlaget.

Skaalvik, C., Uthus, M., Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2020). Opplæring til selvstendighet: et sosialt kognitivt perspektiv. Universitetsforlaget.

Smidt, S. (2014). Introducing Freire. A guide for students, teachers and practitioners. Routledge.

Solhaug, T., & Børhaug, K. (2012). Skolen i demokratiet - demokratiet i skolen. Universitetsforlaget.

Säljö, R. (2012). Schooling and Spaces For Learning: Cultural Dynamics and Student Participation and Agency. In E. Hjörne, G.v.d. Aalsvort, & G. d. Abreu (Eds.), Learning, Social Interaction and Diversity - Exploring Identities in School Practices (pp. 9-14). SensePublishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6091-803-2_2

The Norwegian National Research Ethics Committees. (2021). Guidelines for research ethics in the social sciences, humanities, law and theology. The Norwegian National Research Ethics Committees. https://www.forskningsetikk.no/en/guidelines/social-sciences-humanities-law-and-theology/guidelines-for-research-ethics-in-the-social-sciences-humanities-law-and-theology/

Tjora. (2021). Kvalitative forskningsmetoder i praksis (4. utgave.). Gyldendal.

Toft, B. S., Lindberg, E., & Hörberg, U. (2021). Engaging in a research interview: Lifeworld-based learning through dialogue. Reflective practice, 22(5), 669-681. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2021.1953977

United Nations. (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child

UN Committee on the Rights of the Child. (2009). General commitment No. 12: The right of the child to be heard. https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G09/436/99/PDF/G0943699.pdf?OpenElement

Westheimer, J. (2015). What kind of citizen? Educating our children for the common good. Teachers College Press.

Westheimer, J. (2020). Can education transform the world? Kappa Delta Pi Record, 56(1), 6-12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00228958.2020.1696085