Vol 7, No 3 (2023)

https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.5310

Article

Antecedents of Faroese student teachers’ citizenship behaviour: A study of empirical relationships

Eyvind Elstad

University of Oslo

Email: eyvind.elstad@ils.uio.no

Hans Harryson

University of the Faroe Islands

Email: hansh@setur.fo

Knut-Andreas Abben Christophersen

University of Oslo

Email: k.a.a.christophersen@svt.uio.no

Are Turmo

University of Oslo

Email: are.turmo@gmail.com

Abstract

The school is an important institution in Faroese society, as elsewhere in the world. Among other things, schools must prepare students for further education, professional life, and their duties as citizens. The quality of teachers’ instruction is the most important factor influencing pupils’ learning. The concept of citizenship behaviour highlights the idea that student teachers have a responsibility not only to fulfil their duties but also to contribute to the well-being of their peers. Student teachers’ citizenship behaviour is assumed to influence the functioning of teacher education. Teacher education prepares student teachers and supplies schools with appropriately trained teachers. The purposes of this study are (1) to present an overview of Faroese teacher training, and (2) to explore the statistical relationships between Faroese student teachers’ motivational orientations and their citizenship behaviours. As expected, we find that intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation are related to citizenship behavior. Furthermore, we find that instructional self-efficacy is positively related to citizenship behaviour. Implications for practice and avenues for further research are discussed.

Keywords: teacher education, Faroe Islands, citizenship behaviour, motivation

Introduction

One of the purposes of this article is to present Faroese teacher education to readers outside the Faroe Islands, as well as to analyse relationships between situational perceptions and motivational categories on the one hand and what we call citizenship behaviour within the teacher education environment on the other hand. The former fills a crucial literature gap, as there are very few studies of Faroese teacher education (however, Volckmar, 2019 and Petersen, 1994 have a historical focus on Faroese teacher education) while the latter highlights the importance of citizenship behaviour in Faroese society as well as within the teacher education environment. We assume that student teachers’ thoughts that precede their citizenship actions are interesting to study. By thoughts here, we mean motivational categories as well as perceptions of reality from the practical training.

Citizenship behaviour refers to a set of voluntary actions that individuals take to benefit their organisation or community (Konovsky & Pugh, 1994). In the context of student teachers, citizenship behaviour could involve actions such as helping colleagues, participating in extracurricular activities, and engaging in community service (Christophersen et al., 2015). Behaviour issues, such as absenteeism or poor work ethic, can have a negative impact on citizenship behaviour. For example, if a student teacher frequently misses classes or shows a lack of enthusiasm for teaching, they may be less likely to engage in citizenship behaviour. Instructional self-efficacy, which is an individual’s belief in their ability to successfully perform instructional tasks, may influence citizenship behaviour (Christophersen et al., 2015). If a student teacher has high levels of instructional self-efficacy, they may be more likely to take on leadership roles and engage in activities that benefit their organisation or community (Pendergast et al., 2011). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation can also play a role in citizenship behaviour (Finkelstein, 2011). Intrinsic motivation refers to the internal drive to engage in an activity because it is personally rewarding, while extrinsic motivation refers to the drive to engage in an activity because of external rewards or consequences (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Student teachers who are intrinsically motivated may be more likely to engage in citizenship behaviours because they find them personally fulfilling (Christophersen et al., 2015). By contrast, extrinsically motivated student teachers may engage in citizenship behaviours because they believe such efforts lead to positive consequences, such as recognition or advancement. Overall, these concepts are related in that they all have the potential to influence a student teacher’s decision to engage in citizenship behaviours. Behaviour problems, instructional self-efficacy, and intrinsic/extrinsic motivation can all have a positive or negative impact on citizenship behaviour, depending on the individual and the specific circumstances. For this reason, it is important to explore empirical relationships between the concepts. This is done in this article in the Faroese context which is presented in the following.

A presentation of Faroese teacher training

The Faroe Islands, an archipelago consisting of 18 islands in the North Atlantic Ocean between Norway and Iceland, has approximately 53,000 inhabitants. However, unlike similarly sized countries such as Liechtenstein, Andorra, and San Marino, the Faroes are geographically bounded by the sea and have a language that outsiders cannot understand without language training. Only people who grew up in the Faroe Islands or who have learned the language can communicate in Faroese. The Faroese situation is, therefore, quite special from a European perspective, because a potential teacher shortage cannot be solved with migration, unlike other European countries, whether large or small (Chapter 4 §36 in Løgtingslóg um fólkaskúlan, sum seinast broytt við løgtingslóg nr. 85 frá 16. mai 2022). If a teacher from Denmark, Norway, Sweden, or elsewhere is to get a permanent job in Faroese primary and lower secondary schools, he or she must first take a one-year course in Faroese language and literature teaching. The course is offered at the Faculty of Education, University of Faroe Islands every two or three years. Faroese who have taken a teacher education course in other countries must also pass the listed courses to get a permanent job. Teacher education is, therefore, a matter of vital importance for Faroese society (Harryson, 2023). The present study investigates the motivational antecedents of student teachers’ citizenship behaviour.

The Faroe Islands are part of the Danish Commonwealth and have had extended home rule since 1948, with the question of full independence still very active. The development of society in recent decades has been remarkable, with growth in fisheries creating the economic basis for a modern welfare state. Economically, the Faroe Islands are doing well, perhaps even very well; they enjoy a higher gross domestic product per capita than metropolitan Denmark. The Faroe Islands receive a block grant from Denmark, but the current Faroese government has chosen to receive less of the block grant each passing year.

The Faroese population is conscious of maintaining their mother tongue as a living language in Faroese society, but they are also aware of the importance of being able to communicate with speakers of other Scandinavian languages (and English). Faroese youth are often in the Scandinavian area and communicate well with as many people as possible (Delsing & Åkeson, 2005). The task of the Faroese school is to create conditions for multilingual language proficiency and to create a knowledge base for further education and participation in society as citizens.

The Faroese language, which was initially a variant of old Norse, was maintained over centuries as an oral language and acquired a written form only in the middle of the 19th century. The progress of Faroese literacy in recent decades has been rapid and widespread. The Faroese Islands boast an educated population with little distance between school culture and pupils’ home culture. The school system in the Faroe Islands has had a similar but delayed evolution to the systems elsewhere in Scandinavia, especially the Danish school system. The Danish language has been a central part of the Faroese primary school since the school’s beginnings in the middle of the 18th century—both as a formal language of instruction from 1912 to 1938, and as the language area that the students had to gain special knowledge of afterward (Petersen, 1994, p. 73, 88). The reason why the Danish language has had—and still has—a special status in the Faroese school system is that the Faroe Islands were incorporated into the Danish kingdom in 1814 and have been a self-governing part of the Commonwealth since 1948. The ability to read newspapers and books was initially promoted through home education, with public schools and teacher training coming relatively late (1872). The language of schooling was initially Danish, but a national struggle to have Faroese used in schools became an important issue for Faroese nation-building at the end of the 19th century. Full equality between Danish and Faroese as school languages was introduced in 1938–1939, with Faroese becoming dominant in the years since (Petersen, 1994).

Since 1979, the Faroese national government has had the power to establish rules in all areas of education, but the educational structure largely follows the Danish system. Children start school in the calendar year they turn seven, and there are nine years of compulsory schooling. In the first grade, pupils learn to read Faroese; they begin to learn Danish in the third grade and start English in the fourth grade. When children enter eighth grade, the school schedule consists of both compulsory subjects and electives. Ninth grade ends with a final exam that can be used to apply for upper secondary education. Many students choose to stay in universal school and go through 10th grade, which ends with an extended final exam.

The Faroe Islands experienced a ‘PISA shock’ in 2007 when the results of the Programme for International Student Assessment rated the country’s educational attainment below expectations (Matti, 2009). This created changes in both the school system and teacher training. In 2008, the one-time teacher training institute became part of the sole Faroese university, Fróðskaparsetur Føroya (initially founded in 1965), as a measure to raise its quality. The purpose of Fróðskaparsetur Føroya was to conduct research and teaching at the higher education level. However, the institution did not, at that stage, have university status. It was made a university in 1987, retaining the existing Faroese name and taking the international title of the University of the Faroe Islands. Teacher education was adapted to the university’s formal structure as a bachelor’s degree in the hope of promoting teachers’ professionalism (University of the Faroe Islands, 2022). In 2021, the Faroese Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Culture launched an independent review of the University of the Faroe Islands. The ministry selected a commission consisting of members from neighbouring countries and other small countries, such as Liechtenstein, San Marino, and Andorra. The review team found that the University of the Faroe Islands was ‘working well’ while noting that there was room for improvement (Foley et al., 2022):

The ratio of underlying theory and guided teaching practice appears to be broadly consistent with comparable Nordic societies. No member of the review team felt any reason to express reservations about quality or standards – which were found to be appropriate. Of course, that does not mean that everything is perfect – that is highly unlikely ever to be the case – and there are many aspects in which the programmes can be strengthened and improved, subject, in part, to resourcing (p. 36).

We acknowledge the positive evaluation of Faroese teacher education but want to explore other quality aspects of the programme that were not emphasised by the evaluation commission. The premise of our study is that teachers’ citizenship behaviour is important for creating teacher professionalism and, thus, conditions for pupils’ learning progress. Therefore, citizenship behaviour is the study’s dependent variable. We also assess the relationships between citizenship behaviour and student teachers’ motivational orientations and their self-efficacy in terms of engaging pupils through their teaching activities. We assume that the student teachers' experiences from internships also have an impact on their citizenship behaviour. The reasons for the theoretical assumptions are given below. The second purpose of this study is to explore the strengths of these statistical associations.

Why is citizenship behaviour an important quality dimension in teacher education programmes?

Citizenship behaviour has been a neglected topic in research on teacher education. However, organizational citizenship behaviour has been studied among teachers who have an employment relationship in schools. This is not normally the case for student teachers who are completing an education. Student teachers are participants in an educational program and are usually without an organizational connection to a school in the form of employment. Therefore, the issue of citizenship will be more complex than is the case for teachers who are employed at a school. Likewise, citizenship behaviour is also a quality aspect of a teacher education programme.

Citizenship behaviour refers here to the extra-role actions and behaviours exhibited by individuals within a teacher education programme that goes beyond their formal responsibilities as student teachers: helping their peers with their studies, participating in extracurricular activities, volunteering in their school community et cetera. Attending professional development opportunities. In the context of a teacher education program, citizenship behaviour is crucial for several reasons. Firstly, citizenship behaviour contributes to creating a positive and inclusive learning environment. Student teachers who engage in citizenship behaviours are more likely to foster a sense of respect, and cooperation among their peers. This, in turn, enhances the overall quality of the learning experience. Secondly, future educators are often required to work collaboratively with peers, faculty, and other stakeholders. Citizenship behaviours, such as helping colleagues, sharing resources, and being supportive, promote teamwork and a sense of unity among teacher candidates. This can lead to more effective teacher preparation and collaboration in the future classroom. Thirdly, engaging in citizenship behaviour can be a valuable source of professional growth for teacher candidates. By participating in extra-role activities, aspiring teachers can develop skills and qualities that are highly beneficial in their teaching careers. These activities can enhance useful skills. Therefore, teacher education programs should encourage citizenship behaviour and produce graduates who are active and responsible citizens in the educational community. Further, this can lead to stronger connections between schools and the communities they serve.

In summary, citizenship behaviour in a teacher education program is crucial for fostering a positive learning environment, developing well-rounded and ethical educators, and enhancing collaboration and community engagement. By emphasizing and encouraging citizenship behaviour, teacher education programs can prepare future teachers not only to excel in their classrooms but also to contribute positively to the broader educational community. In the context of teacher education, citizenship behaviour can be defined as behaviours that are not explicitly required of preservice teachers, but that contribute to the learning and well-being of their peers, their school community, and the profession as a whole. Promoting citizenship behaviour in teacher education programs is important because it can help to prepare preservice teachers to be effective and ethical professionals who contribute to the success of their students, their schools, and their communities. The second purpose of this study is to explore the strengths between citizenship behaviour and factors that we assume may be precursors.

Theoretical framework

The quality of teachers’ work is a crucial factor in explaining how well schools function as knowledge-promoting institutions. Furthermore, some studies indicate that experience in the teaching profession contributes to higher-quality teaching work (Chetty et al., 2014; Day et al., 2007). Therefore, teachers must commit to working in that profession. Student teachers’ citizenship behaviour refers to the actions and attitudes that student teachers exhibit as they prepare to become teachers themselves (Christophersen et al., 2015). Here, we focus on a limited aspect of citizenship behaviour that is important in a teacher education context: behaviours that contribute to the positive functioning of the educational institution where they are studying and completing their student teaching, as well as actions that demonstrate a commitment to the profession of teaching and the wider community.

Promoting citizenship behaviour among student teachers is important for several reasons. First, as future educators, student teachers will have a significant influence on the development of their students’ citizenship skills and values (Oplatka, 2009). By promoting positive citizenship behaviour among student teachers, institutions can help ensure that they are better equipped to teach these skills to their students. Second, promoting citizenship behaviour among student teachers can help foster a sense of community and social responsibility within the institution (Somech, & Drach‐Zahavy, 2004). This can lead to a more positive and inclusive learning environment, which, in turn, can have a positive impact on student learning outcomes. Third, promoting citizenship behaviour among student teachers can help prepare them for their future roles as active and engaged members of society. By encouraging them to develop skills such as leadership, critical thinking, and social awareness, institutions can help ensure that student teachers are better equipped to contribute to their communities and tackle complex social issues (Volman & ten Dam, 2015). Overall, promoting citizenship behaviour among student teachers is important because it can help to improve the quality of education, foster a sense of community and social responsibility, and prepare future educators for their roles as active and engaged members of society.

Examples of student teachers’ citizenship behaviour include, in our study, aspects of helping other student teachers with professional questions unsolicited and involvement in organisational work so that all student teachers have the best possible situation. By engaging in these types of behaviours, student teachers can demonstrate their commitment to the teaching profession and contribute to the positive functioning of their educational institutions. This can help create a supportive and collaborative learning environment, and it can also help prepare student teachers for the challenges and responsibilities they will face as teachers. We call this citizenship behaviour. Thus, the endogenous variable in the study’s theoretical framework is student teachers’ citizenship behaviour.

A basic assumption in this study is that citizenship behaviour is related not only to a student teacher’s motivational orientations but also to self-discipline in study work and the instructional self-efficacy that student teachers experience in the practice periods (internships) of teacher education. Student teachers often experience these periods as demanding and, indeed, more taxing than participating in campus teaching (Cohen et al., 2013; White & Forgasz, 2016). Teaching for the first time is inherently unfamiliar and requires a student teacher to overcome challenges by relying on quick thinking: ‘What do I do when a pupil runs into the classroom with a cap on his or her head?’ Through experience, a teacher will develop virtually automatic reactions that lighten the cognitive burden created by the need to deal with pupils’ behaviour problems (Leinhardt & Greeno, 1986; Sweller, 2011). We ask whether there is a statistical relationship between pupils’ behaviour problems in the classroom and the type of citizenship behaviour under investigation. Classroom management is experienced worldwide as one of the greatest challenges that student teachers face during their practice periods, in which they are, in some ways, testing themselves as teachers (Hansen, 2012). We assume that when student teachers experience behaviour problems among pupils, there can be a negative impact on not only their instructional self-efficacy but also their motivation in a broad sense. Therefore, we include pupils’ behaviour problems in the classroom as a theoretical variable that has a negative relationship with the other theoretical categories and with instructional self-efficacy.

We explore the relationship between these motivational orientations and student teachers’ instructional self-efficacy (Schunk, 1995). We assume that there will be a positive relationship between these motivational categories and instructional self-efficacy: higher motivation induces higher self-efficacy, and vice versa. Although the experience will help a teacher ease the cognitive burden created by behaviour problems in students, this challenge becomes a problem-solving process in student teachers’ internships (Leinhardt & Greeno, 1986; Sweller, 2011).

We explore the relationship between behaviour problems in the classroom and citizenship behaviour. The assumption is that a student teacher’s observation that behaviour problems exist in the classroom will be present and that behaviour problems in the classroom are an unfavourable factor for student teachers’ citizenship behaviour (Assumption 1, abbreviated A1).

We also propose that it is worth exploring the relationship between self-efficacy and citizenship behaviour and that appropriate instructional self-efficacy is related to citizenship behaviour. We assume that instructional self-efficacy is favourable to instructional self-efficacy (A2). Further, we assume that student teachers’ motivational orientations are complex. On the one hand, they may be intrinsically motivated (A3), and we assume that intrinsic motivation is an unfavourable factor for student teachers’ citizenship behaviour. On the other hand, student teachers may be extrinsically motivated (A4), and we explore the relationship between their extrinsic motivation and their citizenship behaviour.

Research design, methods, and materials

A cross-sectional approach is a suitable research strategy for exploring statistical associations when student teachers’ citizenship behaviour is the dependent variable because this approach allows for the collection of data from a representative sample of participants at a single point in time. This approach is useful when the research aims to determine the prevalence of a particular phenomenon or to explore the relationships between variables at a specific point in time. In the case of exploring the statistical association between student teachers’ citizenship behaviour and other factors, such as motivational orientation or the perceived demands placed on them in their studies, a cross-sectional approach can provide valuable insights into these relationships. By collecting data from a representative sample of student teachers at a particular point in time, researchers can simultaneously analyse the relationships between the dependent variable (citizenship behaviour) and various independent variables. However, it is important to note that cross-sectional studies have some limitations, such as the inability to establish causal relationships between variables. Therefore, it is essential to use other research strategies, such as longitudinal studies or randomised controlled trials, to further investigate the causal relationships between student teachers’ citizenship behaviour and other factors.

This study’s empirical investigation consists of a survey that was carried out at the Faroe Islands teacher education institution in the autumn of 2021. The survey questionnaire was designed in Faroese. Participation in the survey was voluntary, but a very high proportion of student teachers took part in the anonymous, paper-based survey. A total of 105 student teachers participated. The response rate was 93 %. Hypothesis testing is typically used when a researcher only has a sample of data and wants to make statements or inferences about the larger population from which the sample was drawn. In this case, a researcher uses statistical tests and hypothesis testing procedures to assess whether the observed patterns in the sample are likely to represent real population differences or effects. However, we have data from the entire population and can perform various types of descriptive analyses, calculate population statistics, and draw conclusions directly from the population data without the need for hypothesis testing. We emphasise substantial interpretations of strength relationships.

Measurement instruments

The questionnaire was constructed based on measurement instruments (Table 1) previously reported in the literature and on new constructs based on principles expressed in Haladyna and Rodriguez (2013). In the survey, the student teachers responded to items on a seven-point Likert scale, with four representing a neutral midpoint. The concepts were measured with two to four single items. The analysis reported below was based on five measurement instruments (see Table 1).

Results

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and Cronbachs alpha for the indicators (N = 105)

|

Item |

Text |

Min |

Max |

Mean |

SD |

Skew |

Kurt |

Alpha |

|

Instructional self-efficacy (en). Adopted from Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2007 |

.79 |

|||||||

|

|

To what extent will you, as a future teacher: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

w6 |

Motivate those learners who show little interest in schoolwork? |

2 |

7 |

5.07 |

1.09 |

-0.50 |

0.74 |

|

|

w7 |

Manage to get the learners to believe that they can actually do well at school? |

3 |

7 |

5.79 |

0.90 |

-0.55 |

0.08 |

|

|

Intrinsic motivation (im). Adopted from Vallerand et al., 1992 |

.73 |

|||||||

|

|

I want to be a teacher because: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

w22 |

It is exciting to teach. |

3 |

7 |

5.88 |

1.00 |

-0.76 |

0.35 |

|

|

w23 |

I want others to be interested in learning. |

1 |

7 |

5.87 |

1.07 |

-1.14 |

2.76 |

|

|

Extrinsic motivation (pm). Adopted from Archer, 1994 |

.85 |

|||||||

|

|

It is important to me: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

w25 |

To be looked up to by the other students. |

1 |

7 |

3.74 |

1.73 |

0.06 |

-1.00 |

|

|

w26 |

To be described as the best in the study group. |

1 |

7 |

3.43 |

1.69 |

0.22 |

-0.92 |

|

|

w27 |

To hear that others have a good impression of me. |

1 |

7 |

4.63 |

1.56 |

-0.57 |

-0.19 |

|

|

Citizenship behaviour1 (ocb). NN et al., 2015 |

.94 |

|||||||

|

w60 |

How often do you do the following? I help other students who have difficulty learning out of my own interest. |

1 |

7 |

4.40 |

1.58 |

-0.27 |

-0.60 |

|

|

w61 |

I help other students though it is not my responsibility. |

1 |

7 |

4.58 |

1.51 |

-.209 |

-0.61 |

|

|

Learners’ problem behaviour (pb). Adopted from Grey & Sime, 1989 |

.86 |

|||||||

|

w82 |

Learners talk without being given permission. |

1 |

7 |

4.68 |

1.56 |

-0.22 |

-0.74 |

|

|

w83 |

Learners disturb their fellow learners in their work. |

1 |

7 |

4.62 |

1.50 |

-0.22 |

-0.72 |

|

|

w84 |

Learners do things other than they are supposed to do. |

1 |

7 |

4.08 |

1.60 |

0.15 |

-0.97 |

|

|

w88 |

Learners make unnecessary noise. |

2 |

7 |

3.99 |

1.51 |

0.29 |

-0.97 |

|

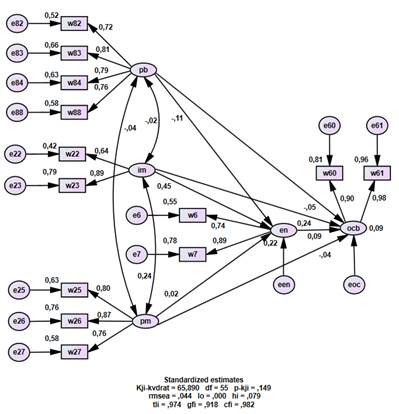

Following Kline (2005), structural equation modelling (SEM) was used in the data analysis. SEM combines psychometric and econometric approaches and is suitable for confirmatory factor analysis and path analysis. Assessments of fit between the model and data were based on the following indices: root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), normed fit index (NFI), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), and comparative fit index (CFI). Pearson chi-square > .05 (not significant), RMSEA < .05 and NFI, GFI, and CFI > .95 indicate a good fit, while RMSEA < .08 and NFI, GFI, and CFI > .90 indicate an acceptable fit (Kline, 2005). The measurement and structural models were estimated using IBM SPSS Amos 27. The indices suggest that the structural models in Figure 2 had an acceptable fit.

Figure 2. The SEM model1. Abbreviations and item wordings are presented in Table 1 (N = 105)

The results of the SEM are shown in Figure 2. The dataset had a small number of respondents (N = 105), which made it difficult to defend statistical testing. Perhaps the relationships could have been statistically significant with a reasonably large sample. Nevertheless, the relationships should be evaluated if they are substantively interesting, which we emphasise here.

The relationships show that intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation were positively related to citizenship behaviour. Furthermore, we found that pupils’ behaviour problems in the classroom were negatively related to student teachers’ instructional self-efficacy, but instructional self-efficacy was positively related to citizenship behaviour. The findings suggest that two types of motivation—intrinsic and extrinsic motivation—were positively associated with student teachers’ citizenship behaviour. This suggests that student teachers who are motivated by their own interests and enjoyment of teaching, as well as those who are motivated by factors such as personal growth and satisfaction, are more likely to display citizenship behaviours.

However, the findings suggest that student teachers who have lower levels of instructional self-efficacy (i.e., their belief in their ability to teach effectively) are more likely to encounter behaviour problems in the classroom. This is not surprising, as teachers who feel less confident in their abilities may struggle with managing disruptive behaviour or delivering effective instruction.

Interestingly, the findings also indicate that instructional self-efficacy was positively related to citizenship behaviour. This suggests that as student teachers become more confident in their instructional abilities, they are more likely to engage in citizenship behaviours like helping colleagues, being proactive in problem-solving, and taking on leadership roles. Overall, these findings highlight the importance of motivation and self-efficacy in promoting positive teacher behaviours and student outcomes in the Faroese teacher education programme.

Discussion

The first purpose of this study was to present Faroese teacher education to a larger audience, given the scant literature on Faroese teacher education in a language accessible to an audience unable to read Faroese. Therefore, the discussion of Faroese teacher training provides an up-to-date overview of the Faroese situation.

The second purpose of this study was to explore the strengths of statistical associations between motivational antecedents and student teachers’ citizenship behaviour. Citizenship behaviour can be considered a civic virtue, similar to conscientiousness. This quality requires authentic behaviour if people are to demonstrate their true potential. Rewarding citizenship behaviour via formal arrangements to maintain social ties by, for example, improving grades in teaching practice can be interpreted as turning an emotional-ethical value into a utilitarian value. However, it is possible to provide a direction for genuine citizenship behaviour among student teachers. Although there was also a positive relationship between intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation, it is not obvious how this relationship should be interpreted; however, we observed a clear positive connection between extrinsic motivation and self-efficacy. In light of this, we chose to interpret motivational orientations as positive factors in the favourable development of self-efficacy. Of course, we cannot prove a causal direction between these categories. The causal connections can be viewed as operating in several ways. In this context, we also pointed out the rather strong associations between the motivational categories and citizenship behaviour. We assume that a teacher education institution should value student teachers’ citizenship behaviour because schools need teachers with professional commitment.

Our findings also show a negative relationship between behaviour problems and instructional self-efficacy. Although the average tendency for behaviour problems in the Faroese classroom is not alarmingly high, our results can be interpreted as meaning that it is not beneficial for the student teacher’s professional development to practice in classrooms with disaffected pupils. However, this is not obvious. What message does this outcome send to educational leaders? Should students with special needs be taken out of class while student teachers are in practice? Do they have to be discovered by the internship supervisor? The vision of an inclusive school implies that there are pupils with special needs in every class. If the practice is to be authentic (i.e., similar to the practice they enter when they graduate), it is important to expose student teachers to this vision rather than overprotect them during practice. We are unable to advocate a clear answer to the question of whether student teachers should be shielded from classes with disaffected learners. Above all, this question concerns which values should be central to teacher education and schooling.

We make no pretension that our study of empirical relationships between these theories is generalisable to a larger population of student teachers. Nevertheless, the response rate on our survey was very high; thus, our findings are valid for Faroese conditions. As we are not aware of other similar studies on factors that must be assumed to be important for citizenship behaviour, we believe that the study is primarily interesting for analyses of Faroese teacher education. However, the empirical evidence from this study can be used for comparison purposes with other similar teacher education programmes in the Nordic region. From such a comparative perspective, the dataset is also interesting (see Elstad et al., 2023).

Strengths and weaknesses

This study has several limitations, including its low number of respondents. Therefore, the study’s results cannot elicit conclusions that go beyond the particular context from which the dataset was collected. A cross-sectional survey also has clear limitations in drawing causal inferences. Educational research is among the fields of study that face the most difficulty in reaching definitive conclusions about the causes of an observed or investigated phenomenon (Berliner, 2002). Nor can this study assert, with a reasonable degree of certainty, the causes of the described outcomes. Therefore, there are threats to the internal validity of the presented findings (Christ, 2007). Only experimental studies can provide a secure evidence base for causal inferences (Campbell, 1986).

Nevertheless, this study is one of the first quantitative surveys of Faroese teacher education to be reported in scientific journals. We consider this to be a strength. In this respect, the study is a first step in the efforts to understand the essential aspects of Faroese teacher education. Our ambition is to use this as a starting point for further studies that combine several methods. Furthermore, the study’s survey had a very high response rate among Faroese student teachers, which is also a strength. Further, the study’s dependent variable—citizenship behaviour among student teachers—is a relatively little-explored field (Christophersen et al., 2015), and this study’s contribution to teacher education research is, therefore, a small but important step in our desire to understand what is important for good teacher education.

Conclusion

The Faroe Islands, being a small community, face unique challenges in terms of their education system, specifically in importing teachers from other countries due to language barriers. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the factors that contribute to the citizenship behaviour of native Faroese student teachers. The present study sheds light on this topic and adds to the limited research available on this subject. The findings of the study highlight the importance of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in shaping citizenship behaviour among student teachers. It is important for teacher training programmes to recognise and cultivate these types of motivation among their students to encourage citizenship behaviour in future educators. Another key finding is that instructional self-efficacy is positively related to citizenship behaviour, indicating that student teachers who have confidence in their ability to effectively teach and manage a classroom are more likely to exhibit citizenship behaviour. However, behaviour problems in the classroom can have a negative impact on instructional self-efficacy, emphasising the need for effective classroom management strategies to support the development of student teachers’ self-efficacy and, in turn, their citizenship behaviour. Overall, this study provides valuable insights into the antecedents of citizenship behaviour among Faroese student teachers and emphasises the importance of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, as well as instructional self-efficacy, in shaping this behaviour. The findings can be used to inform teacher training programmes and educational policies in the Faroe Islands and beyond.

References

Archer, J. (1994). Achievement goals as a measure of motivation in university students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 19(4), 430–446. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1994.1031

Berliner, D. C. (2002). Comment: Educational research: The hardest science of all. Educational Researcher, 31(8), 18–20. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x031008018

Campbell, D. T. (1986). Relabeling internal and external validity for applied social scientists. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 1986(31), 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.1434

Chetty, R., Friedman, J., & Rockoff, J. (2014). Measuring the impact of teachers II: The long-term impacts of teachers. American Economic Review, 104(9), 2633–2679. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.9.2633

Christ, T. J. (2007). Experimental control and threats to internal validity of concurrent and nonconcurrent multiple baseline designs. Psychology in the Schools, 44(5), 451–459. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20237

Christophersen, K. A, Elstad, E, Solhaug, T., & Turmo, A. (2015). Explaining Motivational Antecedents of Citizenship Behavior among Preservice Teachers. Education Sciences, 5(2), 126-145. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci5020126

Cohen, E., Hoz, R., & Kaplan, H. (2013). The practicum in preservice teacher education: A review of empirical studies. Teaching Education, 24(4), 345–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2012.711815

Day, C., Sammons, P., & Stobart, G. (2007). Teachers matter: Connecting work, lives and effectiveness. McGraw-Hill Education.

Delsing, L.-O., & Åkeson, K. L. (2005). Håller språket ihop Norden? En forskningsrapport om ungdomars förståelse av danska, svenska och norska. Nordisk Ministerråd. https://doi.org/10.6027/tn2005-573

Elstad, E., Christophersen, K. A. A., & Turmo, A. (2023). Nordic Student Teachers’ Evaluation of Educational Theory, Subject Didactics, Practice Training, Time on Task and Turnover Intentions. In: E. Elstad (Ed.), Teacher education in the Nordic Region (pp. 287-320). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-26051-3_12

Finkelstein, M. A. (2011). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and organizational citizenship behaviour: A functional approach to organizational citizenship behaviour. Journal of Psychological Issues in Organizational Culture, 2(1), 19-34. https://doi.org/10.1002/jpoc.20054

Foley, M., D’Amelio, M. A., Neslíð, K., Nicolau, M., & Rasch-Christensen, A. (2022). External review of the University of Faroe Islands. Report of the international review team. http://tilfar.lms.fo/logir/alit/2022.12%20External%20review%20of%20the%20university%20of%20the%20faroe%20islands%20september%202021%20%E2%80%93%20october%202022.pdf

Grey, J., & Sime, N. (1989). Findings from the national survey of teachers in England and Wales. In: The Elton Report: Discipline in Schools. HMSO.

Haladyna, T. M., & Rodriguez, M. C. (2013). Developing and validating test items. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203850381

Hansen, H. H. (2012). Aftursvar. Ein yrkislig mynd av teimum, ið tóku læraraprógv frá 2007 til 2011. Føroya læraraskúli og Fólkaskúlagrunnurin. Tórshavn.

Harryson, H. (2023). Teacher education in the Faroe Islands. In: E. Elstad (Ed.), Teacher education in the Nordic Region (pp. 225-250). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-26051-3_9

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principle and practice of structural equation modeling. The Guildford Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6209-332-4_13

Konovsky, M. A., & Pugh, S. D. (1994). Citizenship behaviour and social exchange. Academy of management journal, 37(3), 656-669. https://doi.org/10.5465/256704

Leinhardt, G., & Greeno, J. G. (1986). The cognitive skill of teaching. Journal of Educational Psychology, 78(2), 75–95. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-0663.78.2.75

Løgtingslóg um fólkaskúlan, sum seinast broytt við løgtingslóg nr. 85 frá 16. (2022 mai). www.logir.fo

Matti, T. (2009). Northern Lights on PISA 2006. Nordic Council of Ministers. https://www.norden.org/en/publication/northern-lights-pisa-2006

Oplatka, I. (2009). Organizational citizenship behavior in teaching: The consequences for teachers, pupils, and the school. International journal of educational management, 23(5), 375-389. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540910970476

Pendergast, D., Garvis, S., & Keogh, J. (2011). Pre-service student-teacher self-efficacy beliefs: an insight into the making of teachers. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 36(12), 46-57. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2011v36n12.6

Petersen, L. (1994). Skole på Færøerne i tusind år. En skolehistorisk håndbog. Ludvig Petersen, i samarbejde med Selskabet for Dansk Skolehistorie og Føroya Læraraskúli.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Schunk, D. H. (1995). Self-efficacy and education and instruction. In: J. E. Maddux (Ed.), Self-Efficacy, Adaptation, and Adjustment (pp. 281-303). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-6868-5_10

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2007). Dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and relations with strain factors, perceived collective teacher efficacy, and teacher burnout. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(3), 611–625. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.611

Somech, A., & Drach‐Zahavy, A. (2004). Exploring organizational citizenship behaviour from an organizational perspective: The relationship between organizational learning and organizational citizenship behaviour. Journal of occupational and organizational psychology, 77(3), 281-298. https://doi.org/10.1348/0963179041752709

Sweller, J. (2011). Cognitive load theory. Psychology of learning and motivation, 55, 37–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-387691-1.00002-8

University of the Faroe Islands. (2022). Reflective analysis, 2022: A document prepared to inform the work of the international team conducting the external review of our university. Unpublished manuscript.

Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., Blais, M. R., Briere, N. M., Senecal, C., & Vallieres, E. F. (1992). The academic motivation scale: A measure of intrinsic, extrinsic, and motivation in education. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 52(4), 1003–1017. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164492052004025

Volckmar, N. (2019). The Faroese Path to a Comprehensive Education System. Nordic Journal of Educational History, 6(2), 121-141. https://doi.org/10.36368/njedh.v6i2.153

Volman, M., & ten Dam, G. (2015). Critical thinking for educated citizenship. In M. Davies, R. Barnett, M. Davies, & R. Barnett (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking in Higher Education (pp. 593-603). Palgrave Macmillan US.

White, S., & Forgasz, R. (2016). The practicum: The place of experience? In: J. Loughran, & M. L. Hamilton (Eds.), International Handbook of Teacher Education (pp. 231–266). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0366-0_6