Vol 7, No 3 (2023)

https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.5369

Article

Towards practice-based professional learning by teacher educators: Perspectives from self-study research in Eritrea

Khalid Mohammed Idris

Eötvös Loránd University (Hungary) and Asmara College of Education (Eritrea)

Email: khalididris81@gmail.com

Anikó Kálmán

Budapest University of Technology and Economics

Email: drkalmananiko@gmail.com

Abstract

Teacher education reform has advocated the implementation of widely espoused pedagogic changes in many contexts, particularly in Sub-Saharan African countries. This paper focused on the central agents in the reform process, i.e., teacher educators. Framed within the emerging conceptualizations of practice-based professional development of teacher educators, the study explores perspectives for improving educators’ teaching based on the self-study experiences of the first author while supporting the reflective practices of a group of student teachers in Eritrea. Self-study methods and tools including interactive discussions among colleague educators and critical friends, journaling, and course artifacts were used while developing the findings. The findings identified the dynamics of how researching situated concerns of teaching and learning frames problems of practice and also invokes sources and situations for developing motivations of educators in maintaining inquiry and improvement stances. We argue that such a dynamic is critical in productively engaging with teacher educators' professional learning in practice in similar contexts.

Keywords: professional learning, teacher education, self-study, reflective practices, Eritrea

Introduction

This iteration aims to explore perspectives of professional learning of teacher educators (TEs) during a self-study initiative for improving reflective teaching practices in a teacher education context in Eritrea. Initial teacher education (ITE) establishments in contexts similar to the study, i.e., Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), have been criticized for being part of the problem in the calls for transforming practices from transmission-driven interactions towards more learner-centred and engaging approaches of teaching (Schweisfurth, 2011; Vavrus et al., 2011). Far from modelling the espoused approaches, ITE establishments could be a preparation for more restricted and authoritarian forms of professionalism (Harber, 2012). Accordingly, providing professional development opportunities for TEs (Barnes et al., 2018; Vavrus et al., 2011), basing ITE pedagogical interactions on schooling realities (Akyeampong et al., 2013), and developing a more nuanced understanding of the factors that influence the agency of TEs (Stutchbury, 2019) seem among the salient perspectives in improving the roles of ITE and TEs. However, there is a limited understanding of possibilities for professional learning and developing professionalism when TEs in such contexts engage in self-initiated improvements in practice.

In the SSA contexts, calls for practitioner-driven research was made in revitalizing the roles of ITE, for example in Uganda (O’Sullivan, 2010), Malawi (Mayumbelo & Nyambe, 1999), and Eritrea (Demoz, 2011). Accordingly, action research is encouraged by ministries and institutes of education in SSA to improve practices, professionalism, and ITE-school linkages (Worku, 2017). Yet, in reality, action research is “widely phrased, but poorly understood and practiced concept” (Worku, 2017, p. 740). Among the main reasons for this is that in many contexts action research is “generally externally mandated, and tends to take place as a fulfilment for programs of higher education which are targeted at improving practice in settings such as schools and classrooms” (James & Augustin, 2018, p.333) without necessarily problematizing the positions and roles of TEs in ITE settings. As a genre of practitioner research, self-study, on the other hand, foregrounds the ‘self’ in drawing on the experiences of TEs as a resource for research and urging TEs to be critical of their roles as researchers and educators (Feldman et al., 2004 as cited in McCool & Myers, 2021). Hence, self-study affords methodological repertoires (Ritter & Quiñones, 2020) in problematizing and improving TEs’ roles in modelling espoused teaching approaches in school systems and meaningfully developing their professionalism (Vanassche, 2022).

Partly due to TEs’ limited exposure to espoused practices, e.g., reflection, learner learner-centred pedagogies, (Abdella & Fataar, 2021), the development of TEs’ contextual competencies in practice becomes imperative. Nguyen (2023) identified competencies that need to be developed by TEs in challenging contexts: knowledge and skills in disciplinary and pedagogic domains, ethical manner, motivation, and self-reflection on personal values. Such competencies relate to the studies that highlighted significant interconnections between TEs’ normative beliefs, relations with student teachers, and teaching methods (Malm, 2020). In the Eritrean context, the potential of dialogic interactions is a promising practice for reinvigorating the role of teacher education in modelling and implementing the idealized learner-centred interactive pedagogy in schools (Tadesse et al., 2023). In this study, we explore such a dialogic space created among colleague educators and critical friends as part of a self-study initiative taken by the first author (FA) motivated by a situated concern of improving the facilitation of reflection. Through our exploration, we aim to identify and share perspectives of professional learning in a context where the competencies of TEs in managing teaching practices are barely problematized. Accordingly, the guiding research question is: What perspectives could be identified about the professional learning of TEs during self-study research on improving the facilitation of reflective practices in a teacher education context in Eritrea?

Practice-based professional learning by teacher educators

The professional learning of TEs is an independent field of research (Ping et al.,2018; Vanassche et al., 2021). Loughran (2014) outlined what he called shaping factors in the professional learning of TEs during their career: the transition from school teaching to higher education, the nature of teacher education, and the need for researching teacher education practices. Similarly, Ping et al.’s (2018) review synthesized the contents, mainly the pedagogy of teacher education (Korthagen, 2016), activities, including researching own practices, and intrinsic motivations for professional learning of TEs. The research in this field hence points to the centrality of practice, research, and intentional and improvement-oriented interactions as inherent features of TEs’ work (MacPhail et al., 2019). Vanassche’s (2022) propositions for conceptualizing, researching, and improving TEs’ professionalism highlight enacted instead of demanded, i.e., standard-driven, development orientation. Hence, the practice-based approach is reflected in questions that critically explore practices instead of evaluating it, using questions like ’ What happens?’; ‘Why is this happening’; ‘What do we think of this and why?’; and ‘Should we try to change this practice and why would this change be an improvement?’ (Vanassche, 2022, p. 3).

The practice-based conceptual model by Vanassche et al. (2021) calls for enacted practices to be the starting point of the professional development of TEs. The model suggests that since TEs “cannot not model” their teaching practices, TEs must adopt a stance as “how I teach is the message” which includes orientations towards inquiry, contextual responsiveness, caring, and self-regulation (Vanassche et al. 2021, pp. 18-19). Though local, national, and global trends influence factors in what and how TEs perform and learn, the model calls for intentional support for the growth and empowerment of TEs to constructively mediate influences in the interest of student teachers’ learning. Such developments in the field of professional learning of TEs show an increased realization that the relevance of teacher education institutions and programmes depends on the quality of engagements of TEs in and with their practices. A related issue raised in the literature is how professional learning initiatives are linked to the intrinsic motivations of TEs (MacPhail et al., 2019; Malm, 2020) on the one hand and how such a motivation “is gradually formed by professionals’ effort into work” on the other (Nguyen, 2023, p. 1). Such insights seem to contradict calls for expert-driven training of TEs in low and middle-income contexts when implementing explicitly encouraged teaching practices as the learner-centred pedagogy (Barnes et al., 2018; Bremner et al., 2023).

Initiatives for improving the facilitation of reflection in teacher education could be an enabling factor for enacting learner-centred pedagogy (Bremner et al., 2023) on the one hand and a viable context for exploring practice-based professional learning possibilities on the other. This is mainly because reflective teaching is associated with taking responsibility for one’s professional development (Zeichner & Liston, 2014). Despite the popularization of reflection in teacher education, its influences on student teachers and indeed in school practices could be counterproductive if the right conditions are not in place (Russell, 2013). Marshall’s (2022) synthesis on experiences of facilitating reflection identified factors and facilitation tasks contributing to improved practices including building relationships through a relational reflective process, modelling, and being learner-centred. Hence, the extent to which TEs are learning to be reflective on their practices prefigures the quality of co-engagements and pedagogies they implement in supporting the reflective experiences of their student teachers (Senese, 2017). This is in line with the ‘how I teach is the message’ stance discussed earlier. A case for exploring professional learning possibilities becomes particularly relevant when TEs express a desire to improve in the very practices they are expecting from their student teachers, i.e., becoming reflective practitioners. This is more so were addressing the professional learning needs of TEs in practice is not part of an institution’s explicit goals (MacPhail et al., 2019).

In line with the developments towards practice-based models, addressing and developing the professionalism of TEs in practice entails adapting pedagogies of investigation and enactment (Vanassche, 2022). Self-study research offers a methodological framework by centring TEs' biographies and pedagogic reasonings (Loughran, 2019) and by encouraging improvements-oriented interventions on situated concerns of practice (LaBoskey, 2004; Pithouse-Morgan, 2022). The epistemological underpinnings of self-study research resonate with developments toward practice-based professional learning because it aligns with the “view of teacher educator knowledge as that which manifests itself and constantly develops in and through practice” (Vanassche & Berry, 2020, p. 178). Furthermore, self-study research’s contributions to the scholarship of teacher education (Pithouse-Morgan, 2022) tend to be embodied in the espoused models of practice-based professional learning. Hence, we argue the empirical context of this study which is based on situated concerns of practice, i.e., improving facilitation of reflection, and the explicit adoption of self-study research affords a viable ground for sharing perspectives on improving the professionalism of TEs in practice in challenging teacher education contexts.

Methods

Context

The Asmara College of Education (ACE), located in the northwestern part of the capital city, became the only teacher education establishment after a national higher education restructuring initiative in 2018. It set up a one-year postgraduate diploma in education (PGD) program to improve the pedagogical competencies of subject teachers. Before this time, teacher education in the country was mainly offered at undergraduate levels for candidates who acquired minimum passing grades at a national secondary school leaving examination. This trend was seen as problematic as it fuelled unconstructive images about education studies in general and in teacher education in particular in the backdrop of deteriorating professional esteem of the teaching profession (Hailemariam et al., 2010).

The PGD program sought to redress the challenges by admitting practicing teachers in schools with commendable undergraduate academic performances. Yet, the practices of TEs were barely addressed as trends of frontal teaching and examinations seemed to persist in the PGD program. Such trends of teaching at the college did not seem to fit the profile of the candidates with at least 3 years of teaching experience and who represented diverse locations, cultures, and socio-economic composition of schools in the country. This context has put the PGD program and more specifically practices of the TEs in the spotlight because student teachers came from diverse schools where professional development opportunity for meaningfully reconciling espoused teaching practices with schooling realities was very limited. The college made attempts to include engaging practices through its assessment guidelines which included reflective requirements. Reflective requirements, with an assessment weight of 20% out of total course marks, were prescribed seemingly leaving spaces for modalities of enacting reflective teaching for TEs in respective courses.

This space was seen by the first author (FA), an educator in the college for over a decade, as a professional learning context in creating enabling situations for facilitating reflective practices among a group of student teachers. The FA was concerned about how reflective assignments were managed in a fragmented manner within and across courses despite student teachers’ explicit preferences for reflective learning opportunities (Idris, 2023). There was a general trend of submitting reflective reports from individuals and groups of student teachers for fulfilling course assessment requirements without necessarily linking them to professional learning practices. Specifically, purposes and pedagogy in facilitating reflective learning practices were not clearly articulated in course designs and were hardly part of educators’ formal and informal discussions.

In this context, the FA took up the challenge of studying situations and embedding reflective learning experiences in his course, Social Science Teaching Methods (SSTM). The self-study drew inspiration from previous initiatives by a team of education, of which the FA was part, who are motivated to improve teacher education practices from within (e.g., Idris et al., 2021). Accordingly, a self-study research approach was adopted in learning to improve reflective facilitation during one academic semester.

Researching teacher educators’ practices

The self-study research approach aims at increasing understanding of “oneself; teaching; learning; and the development of knowledge about these” (Loughran, 2004 as cited in Ritter & Quiñones, 2020, p. 341). Accordingly, self-study research was adopted because it afforded focus on TEs' concerns of practice with orientations for improvements (LaBoskey, 2004; Vanassche & Berry, 2020) and encouraged exposition of process-based uncertainties and vulnerabilities in facilitation roles and positions (Berry, 2008). The research genre fits with the FA’s initiative for studying intentional practices of embedding reflective learning in his course.

During a course of 16 weeks, with four formal contact hours per week, individual and collective reflective opportunities were intentionally linked to the SSTM course objectives and contents. Student teachers were required to read identified course chapters before a whole class series of reflective discussions based on the contents of readings and school teaching experiences. Afterward, individual student teachers were required to submit reflective essays (n=6) based on class discussions and chapter readings. The FA was committed to providing timely feedback (n=6) to encourage and support learners’ reflective writing capabilities. Additionally, the SSTM course design required groups of student teachers to research identified learning themes[1] and develop reflective actions to improve learning challenges during the semester. The rationale behind this design was to meaningfully contextualize subject methodology issues discussed during the course and link reflective practices with the professional learning of the student teachers during the semester.

In the process of studying to improve initiated facilitation practices, the interactive nature of self-study has enabled the systematization of the research process (Fletcher, 2020). The FA has proactively sought to engage colleagues and critical friends in practice-based discussions within the college and beyond in making sense of and improving facilitation processes. A key feature of the practice-based model for the professional development of educators is engagement in intentional collegial discussions based on practices in real-time (Vanassche et al., 2021). Timely collegial discussions have not only made sense of initiated practices but also shaped the way the SSTM course was facilitated. A colleague educator[2] has volunteered to attend class sessions (n=15) and immediately engaged in discussions with the educator-researcher about course processes and practices. These interactions were a critical mirror for the FA to question and improve intentions and initiatives.

Focused group discussions with PGD educators (n=6) who were teaching other subject methodologies and core education courses were arranged (n=2) during college-level initiatives to improve reflective practices. The first author also conducted formal discussions with the acting dean of the college (n=3), and more frequent informal discussions, because of his particular interest in improving reflective practices at a college level. Beyond the college, discussion meetings (n=6) were arranged with a team of critical friends (n=3) with whom the FA has previously engaged in studying and improving course practices at a similar study site (Idris et al., 2021). In self-study research, critical friendship is a viable method that affords supportive and challenging feedback in generating alternative interpretations of practice especially when the critical friends are more than two and have developed personal and professional relationships over time (Fletcher et al., 2016). The student teachers (n=45) had social science fields academic and teaching backgrounds. With an average age and school teaching experience of 37 and 11 years respectively, the student teachers came from five regions representing four ethnic groups in the country[3]. Such diversity presented a unique facilitation challenge while learning to embed reflective teaching practices during the SSTM course.

Ethical considerations

During the interactive drives, the FA was learning about the “unique ethical complications that emerge during self-study research and the necessity to anticipate how these complications influence not just the empirical product but, perhaps more importantly, our professional and personal relationships” (Cuenca, 2020, p. 473). Accordingly, the FA was keen to monitor his interactional ethics by proactively creating situations, e.g., organizing presentation forums to share initiatives and emerging insights, to communicate his personal and professional experiences (Cuenca, 2020) among colleagues, the college leadership, and the student teachers during the semester. Moreover, colleague educators signed a consent form for the formally recorded discussions used as data in this study.

Data and Analysis

The main sources of data used in developing this study are the audio-recorded (over 18 hours) and transcribed discussions (in over 48,000 words) conducted with colleagues and a team of critical friends during the semester. The discussions were mainly conducted in a local Tigrinya language with frequent use of English. In addition, the reflective journal of the FA, with 18 entries, written during the semester is used. Reflective journaling followed a general format of describing ongoing course practices, analysing issues by relating them with teaching practices, biographies, assumptions, etc., and drawing meanings and actions that were meant to influence facilitation practices (Bassot, 2016). Reflective journaling was an important self-study practice not only as a source of data but as modelling strategy for the student teachers who were challenged to write reflections. Hence, apart from the reflective journal kept as part of the self-study, the FA was motivated to write and share his reflections based on class discussions and course readings in a locally networked and offline Moodle© platform created for the course. This initiative was as much pedagogic as it was inquisitive in explicating facilitation intentions, reasonings, and uncertainties of the FA among the student teachers (Loughran & Berry, 2005). Table 1 summarises the data sources.

Table 1. Interactive and self-reflective data sources

|

Interactive |

Self-reflective |

|||

|

Discussion |

Frequency |

Time (audio recording) |

Transcripts (words) |

|

|

Colleague educator |

15 |

07 h, 22 min |

21,369 |

Journal entries (n=18) |

|

Critical friends |

6 |

06 h, 42 min |

13,011 |

Shared reflections (Moodle), (n=5) |

|

PGD educators & leadership |

5 |

03 h, 40 min |

13,620 |

|

A thematic analytic procedure was applied and included listening to audio records, reading transcripts, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing, defining, and naming themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The use of MS Excel spreadsheet was instrumental in the iterative process of generating themes. In line with the focus of this study, facilitation experiences that challenged and improved the FA’s professional learning were identified to publicize perspectives from a situated problem of practice, a characteristic feature of self-study research (Pithouse-Morgan, 2022). Accordingly, the themes identified as findings frame practice-based experiences of and for professional learning while studying to improve the facilitation of reflection among a group of student teachers in one academic semester. Data excerpts used in the findings were translated by the FA.

Professional learning in practice

In this section, we discuss the findings of the intentional and interactive initiative of studying to improve the facilitation of reflective practices. The sub-sections are organized to explore interactive experiences that framed problems of practice (Bullock & Ritter, 2011) which in turn informed the self-study during the SSTM course and inspired the identification of sources and situations for motivations in developing educators’ contextual competencies.

Problematizing existing practices

The self-study intervention on improving the facilitations of reflective practices in the SSTM course of the PGD program has revealed existing college practices that tended to be at odds with meaningfully embedding reflection in courses. This was manifested in the way the facilitations tended to be essentialized (Beauchamp, 2015) on the one hand and how existing practices of examinations highlighted a disjuncture with the reflective requirements on the other. First, modalities for adopting a uniform assessment guideline seemed to be among the main preoccupations of the college community in managing the reflective requirements within the PGD courses. Hence, the Academic Commission of the college has recommended a forum, in which the FA was tasked to lead with colleague educators in sharing understanding about the nature and processes of facilitating reflective teaching. The following views of the acting dean conducted in preparation for the forum reflected such concerns.

I cannot say we [PGD educators] completely understand the notion of reflection, we seem to be assuming reflection to be essay writing, at best we expect [learners] to be critical not in an essential sense of the word but write something on an article that was read, so it is almost like a reaction (AD, 10.03.2021).

A lot of learners’ problems and anxiety come from not knowing how to write a reflection, i.e., not only how to engage in the process of reflecting about their own practices, own biases but also how to put it in writing (AD, 10.03.2021).

These excerpts portray challenges in articulating purposes and processes of reflective practices in teacher education at the study college. The first excerpt highlights a practice of reflection in the submission of reports. Such trends relate to Russell’s (2013) warning that reflective practices may do more harm than good when educators hardly elaborate on the meaning of reflection and link reflective experiences with the professional learning of student teachers. Accordingly, reflective requirements that focused on disparate accounts of experiences seemed to be at odds with conceptions of reflective learning as a process that needs intentional guidance and scaffolding (Allas et al., 2020). The second excerpt seems to underline this in that the reflective assignments may not be adequate platforms to not only learn reflectively but also develop skills of writing reflections when they are simply left for student teachers without intentional support.

PGD educators’ limited proficiencies with purposes, nature, and debates of reflective practice in teacher education seem to have led to instrumentalized and fragmented handling of reflection as a mere fulfilment of program requirements (Idris, 2023). This may not mean that the reflective assignments did not have educational value for the student teachers, but they may not have meaningfully facilitated bridging school experiences and professional learning practices. In other words, reflective experiences at the college may have had limited influence in meaningfully allowing the student teachers to value their schooling experiences and challenging enough to reframe their assumptions about teaching (Berry, 2007).

Secondly, existing college arrangements of examinations were constraining in appreciating and enacting facilitation practices that fit with the fluid, context-specific, ongoing, and iterative nature of reflection (Marshall, 2019). While the student teachers were learning to think reflectively and write reflections about their experiences, positions, etc., often about given materials, they were also required to prepare for quizzes mainly from lectures and course readings. Consequently, student teachers shared how requirements for writing reflections and preparing for quizzes were “overburdening” them (FA Reflective journal, 22.02.2021). In this context, a critical friend’s perspective was emblematic of the existing constraints of testing practices at the college.

The ill effects of the prevalence of the pedagogy of examination are manifold, examinations are done mainly individually learners may not be motivated to interact and collaborate and accordingly develop a competitive stance, and educators may easily assume other tasks that may not be directly related to improving their teaching duties because they know they are mainly required to evaluate their learners using exams (Critical friend 1, 07.03.2021).

Concerns of the learner-teachers about the overburdening of requirements were not necessarily linked to the intensity of requirements but to practice arrangements (Kemmis, 2022) of reflective practices and examinations which seemed to have assumed a competing epistemological connotation. Practices of controlled quizzes/exams were often associated with levels of mastery of prescriptive contents, relying on limited and limiting study skills (e.g., rote memorization), and least involvement in collaborative practices with peers. Persistent college practices that reinforced examinations seem to be prefigured by views about the superseding role of theory in guiding practices (Raelin, 2007). This translates into an excessive focus on lecturing and examinations in ‘delivering’ and checking the extent of theoretical knowledge and affording passing attention to experiences and realities of student teachers.

On the other hand, epistemologies of reflective practices emanate from viewing teachers as persons whose experiences, biographies, and emotions matter in and for their learning (Korthagen, 2017). Hence, college practices were grappling with existing practices of the pedagogy of examinations which were at odds with reflective practices. Most of the PGD educators, including the first author, were not necessarily proficient with the epistemologies of reflection as an adaptive, collaborative, and transformative process (Glasswell & Ryan, 2017). Yet, the interactive spaces created as part of this study highlighted uncertainties and tensions with the practice of facilitating reflection at the college mainly because of a shared concern for improving teaching practices. This was captured by a colleague PGD educator during one of our recorded conversations as follows.

Student teachers’ repeated demands to know more about and learn through reflection is evidence enough that we should collaborate in learning to improve our reflective facilitation in meeting their explicit needs (PGD educator 3, 11.03.2021).

These experiences show the role of intentional dialogue among educators in exploring practical concerns and possible actions for improvements, a central feature of practice-based professional development (Vanassche et al., 2021). In the next section, we discuss how the problematization of existing practices informed the self-study on improving the facilitations of reflection during the SSTM course.

Researching practices

The problematization of existing practices informed the introduction of a more systematic enactment of reflective facilitations in the SSTM course in three main ways: developing a responsive course design, creating collaborative reflective opportunities, and educator modelling. The main intention of the SSTM design was to show the value of reflection by focusing on the student teachers’ learning practices during their PGD coursework in the semester. The following views which the FA shared with the visiting colleague educator capture the intentions of the course design.

The intention is for the student teachers to practice methods discussed in the SSTM course during their studies so that they learn to reflect to improve their learning challenges at the college on the one hand and learn practical applications in learning and teaching through particular methods, so it is a win-win arrangement (FA, 11.03.2021).

Hence, a more purposeful, integrated, and practical arrangement was sought in embedding reflective teaching during the course. The drive was to develop a practical and conceptual articulation of the need for reflection in teachers’ practices by focusing on the social and material learning realities during the semester (Van Beveren et al., 2018). Distancing from essentializing tendencies of reflections was sought by trying to broadly frame how reflective experiences could be integrated to support learning practices in all the PGD courses (Beauchamp, 2015).

Another arrangement introduced in the SSTM course was the series of intentional collaborative reflections created in the classroom. Groups of student teachers were required to prepare and share for a series of briefing sessions (n=8) in class during the semester on how they were learning to frame their learning challenges and possible actions taken to improve them. Yet, the differing course arrangements in the program challenged such a reflective arrangement. The transmission-dominated teaching and learning interactions of the PGD courses that challenged the introduction of process-based reflective engagements were manifested in many ways. For example, a practical challenge during the semester was the shortage of LCDs to support the facilitation of courses. Material shortages are reported as a constraint while implementing engaging teaching approaches in the SSA teacher education contexts (Schweisfurth, 2011; Vavrus et al., 2011; Westbrook et al., 2013). On the other hand, the following reflective journal entry captures a pedagogical orientation that underpinned the expressed shortages of much-needed teaching equipment.

The use of power points and LCD technology seems to be both a pedagogical and practical challenge among educators which the college has to address head-on in any professional development initiatives (FA Reflective journal, 11.02.2021).

The pedagogical challenge was how we [PGD educators] were learning to balance transmission-oriented teaching with attending to reflective opportunities as the former seemed to have overridden the latter. Consequently, the SSTM course that required groups to spend time reflecting on learning experiences was challenging to enact as they were “not paying adequate attention to the process involved in refining their reflective questions” (Reflective journal, 29.03.2021). Accordingly, student teachers had, at best, fragmented opportunities to reflect on themselves and their learning experiences, practices that would have otherwise allowed them to encounter experiences congruent with learner-centred pedagogy (Bremner et al., 2023).

Yet, adopting a self-study approach in the SSTM course created affordances in not only explicating concerns of practice but also in showing how enacting reflective practices required collective co-engagement and learning (Boud & Walker, 1998). Accordingly, the FA’s initiative of writing and sharing regular reflection was a form of explicit modelling (Loughran & Berry, 2005) which was meant to concretize the intentions of the course for the FA and the student teachers. Such practices included modelling roles of reflection in problematizing and improving course facilitation by writing and sharing a series of reflective essays with the learners in a locally connected MoodleTM platform created for the course. The FA was also keen on showing the influences of his reflective engagement in improving the course. The following journal entry reflects such a stance in the context of class discussions on implicit purposes of history teaching towards coverage of prescribed contents and control of class norms at the expense of a much-needed engagement with historical interpretations (Barton & Levstik, 2010).

During the discussions, I hinted at how we [PGD educators] have a controlling tendency. Perhaps it is important to be more explicit on how this controlling process happens during facilitation sessions, e.g., one learner shared in his reflection how their discussions (week 01) were cut short because of ‘time shortages’. This was a good reminder of how we should show challenges discussed in course readings in our actual practices, and invite learners on how we could go forward in improving them (FA Reflective journal, 11. 02.2021).

Such stances reflect a growing scholarship in teacher education that encourages a pedagogy of explicating facilitation reasonings with student teachers (Loughran, 2019). Adopting a pedagogy of investigation, as self-study, seems to facilitate the concretization of practical reasonings during the enactment of practices that underpin the professional learning of educators (Vanassche et al., 2021). Situations for developing educators’ contextual competencies (Nguyen, 2023) in the study site are discussed in the next section.

Motivations for improvements

The interactive spaces created as part of the self-study research revealed critical situations and the central roles of educators’ motivations while enacting active teaching approaches as reflective practices. The data show three main sources of motivations of educators in developing contextual competencies (Nguyen, 2023) in improving teaching practices in general and practices of facilitating reflection in particular at the study college. These include increased recognition of the suitability of reflective practices, being responsive to student teachers’ feedback on their learning experiences during the semester, and sensitivities toward the extent of educators’ readiness to enact pedagogic changes. Reflection seemed to have captured the attention of the student teachers and educators alike during the program partly due to its inclusion as one formal way of assessment in all the courses and for its potential to embody the explicitly encouraged learner-centred pedagogy in the Eritrean school system (Tadesse et al., 2023). A colleague PGD educator justified the increased recognition of the suitability of reflection as a teaching approach in the college as follows.

I think the emphasis of the college should be on reflection rather than discipline-related knowledge because we need to develop new experiences based on how theories [of teaching] relate to actual schooling practices of the student teachers (PGD educator 1, 11.03.2021).

Such recognition is an essential element in the practice-based professional development model as educators explicate professional stances congruent with contextual responsiveness and critical and inquiry orientations (Vanassche et al., 2021). This stance further highlights the potential of dialogic teaching in and through reflection as the program was being conducted in the backdrop of common teacher-dominated class interactions despite persistent idealization of learner-centred and interactive teaching practices in the Eritrean context (Tadesse et al., 2023). Yet, the extent of learner-centeredness of the PGD program depends on how educators commit to responding to student teachers’ needs. The following discussion excerpt with the visiting colleague educator conducted after a mid-term assessment of the reflective experiences of the student teachers in the SSTM course indicates tension and a source of motivation for improving teaching practices at the college.

I think there should be a way where student teachers get to have a say on how they are assessed or taught, they need to communicate …they should not see the PGD experience as a repetition of what they know in their undergraduate studies (Visiting educator, 16.03.2021).

The tension and the source of motivation revealed in this excerpt is the urgency of coming out of the inertia of transmission-oriented teaching practices at the college. Motivations arising from the need to adapt responsive teaching approaches in line with the explicit calls of the student teachers for enhanced engagement and interactivity highlight the role of teacher education-related factors in contributing towards integrating learner-centred pedagogy in the school system (Bremner et al., 2023). However, educators' practices are constrained, not necessarily determined, by institutional and national contexts (Vanassche et al. 2021). This implies educators’ agency in improving practices provided they are empowered in ways that acknowledge their “work and the expertise it reflects, and on the other hand, creating opportunities to further develop and improve the expertise” (Vanassche et al. 2021, p. 20). A discussion with the acting dean in preparation for the college-level forum on reflective practice indicated a step towards such empowerment in the study college as follows.

I believe the motivations of colleague educators are an issue, we work in a context where centralized directives exclude the interests of [some] staff members [often concerning opportunities for acquiring higher degrees], hence despite drives and wishes for improvements we observe staff members focus on mechanical instead of developmental aspects of their practices. I think we should think about why staff members may resist coming out of their mechanical shells. I don’t think we have issues with the potential and need of our staff for improvements, I believe such forums could nudge us to come out of routine practices (AD, 05.03.2021).

This view resonates with scholarships on moving beyond deficit approaches to professional development and adopting a more critical perspective into the lived realities and aspirations of teacher educators and schoolteachers in the Sub-Saharaharn contexts (Stutchbury, 2019; Tao, 2013). Staff development, which often entails studies abroad in the study context as there are no doctoral programs in the country, is managed by the national higher education office with strict eligibility criteria. Promising former experiences at college towards practice-based professional development with the possibility of accessing opportunities to secure a much-sought doctoral degree was discontinued during the restructuring initiatives (Posti-Ahokas et al., 2021). However, such initiatives have motivated many colleagues, including the FA, to appreciate what could be possible in improving learning contexts while strengthening contextual competencies from within.

Discussion and implications

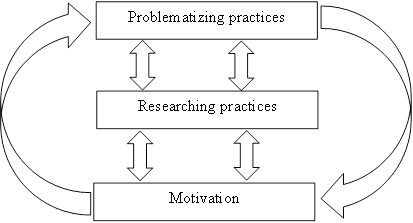

In this study, we shared perspectives on educators’ professional learning in and for practice, based on a self-study research initiative in a teacher education context in Eritrea. The findings show how researching practices, based on a situated concern, has initiated a collective problematization of existing practices and identifying sources and situations of motivations for improving a learning context. Figure 1 captures these dynamics by highlighting the central role of research in creating interactive contexts for problematizing practices and developing motivations which we argue prefigures TEs’ continued co-engagements in practice-based professional learning and improvements. This experience also relates to the role of TEs’ intrinsic motivations in engaging with self-initiated professional learning practices (MacPhail et al., 2019; Nguyen, 2023; Ping et al., 2018). Congruent with the practice-based professional development model (Vanassche et al. 2021), the experiences of this study show how the collective problematization of existing practices inspired the FA in mobilizing research to improve a learning context. This process has led to identifying sources and situations for invoking professional motivations in sustaining research practices. These include establishing a collective consensus on the need for pedagogic change, in this case, reflective teaching, developing professional integrity in meaningfully engaging the student teachers (Demoz, 2021), and sensitivities for the capability constraints (Tao, 2013) of TEs in initiating improvement-oriented practices. In the latter, a notable constraint in the study college was the rigid and certification-centred professional development scheme (cf. Isotalo, 2017).

Figure 1. Dynamics involved in practice-based professional learning

|

A notable theme in the findings is how the practice of examinations could undermine the potential of reflective practices and limit professional learning possibilities. Exam practices that focus more on content/educational knowledge and less on applications of school practices based on challenges of teaching particular groups of learners and/or topics may not be a relevant learning experience in college-based teacher education courses (Akyeampong et al., 2013). Controlled exams could further limit educators’ continued co-engagements with student teachers as the contents and practices of testing could unconstructively divert focus and resources from the learning process. Accordingly, possibilities for practice-based professional learning could be constrained. This is because TEs’ tendencies to consolidate roles as transmitters of knowledge rather than models of advocated approaches tend to be reinforced and reproduced through the practices of exams (Barnes et al., 2018). Given the profile of the student teachers in the study college, reflective opportunities could not only allow learning diverse school challenges but also generate a reframed understanding of practices and developing intentional stances in improving schooling contexts (Mayumbelo & Nyambe, 1999).

Researching teaching presents unlimited possibilities for (a) interrogating established practices with untoward consequences (Kemmis, 2022); (b) positioning courses as a viable context for collaborative inquiry and improvements (Idris et al., 2021); and (c) explicating tensions (Berry, 2008) and pedagogic reasonings (Loughran, 2019) in TEs’ work that are central features of the pedagogy of modelling in teacher education (Korthagen, 2016). In this regard, program arrangements and roles of TEs in similar study contexts should shift from academic to practice epistemology in “paying special attention not so much to the content of our knowledge but to the processes that encourage more knowing-in-action and their outcomes” (Raelin, 2007, p. 496). In this study, initiatives for researching the facilitations of reflection have allowed the FA to position and appreciate refined roles because processes of explicating intentional practices served as pedagogic platforms and contexts of inquiry in simultaneously modelling and improving practices (Idris et al., forthcoming). This experience concurs with the perspectives that TEs’ “professional identities emerge in their practices” (Vanassche et al., 2021, p. 29, emphasis in original).

Emergent perspectives during the self-study highlight the role of course designs and committed collaborative practices (Idris et al., 2021) while enacting pedagogic changes for meaningful learning. Crucially, the FAs’ practices of modelling facilitated in better appreciation of the notion of “presence” in teaching which was defined as

a state of alert awareness, receptivity, and connectedness to the mental, emotional, and physical workings of both the individual and the group in the context of their learning environments, and the ability to respond with a considered and compassionate best next step (Rogers & Raider-Roth, 2006, p. 265).

Limitation

A self-study research approach has facilitated in exploration of problems of practice and revealing the perspectives of practitioners. However, discussion of the findings and perspectives need not be seen as common and representative views of the college community in the study site. Hence, the interpretive accounts of the findings and ensuing generation of arguments about professional learning could be read as perspectives emerging from a particular case of an intentional improvement initiative in practice. Yet, we hope to have shed light on the professional learning needs and possibilities for improvements of the under-researched professional group, i.e., teacher educators, particularly in the SSA teacher education contexts.

References

Abdella, A. S., & Fataar, A. (2021). Teaching Styles of Educators in Higher Education in Eritrea. Journal of Higher Education in Africa, 19(1), 45-62. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/48645902

Akyeampong, K., Lussier, K., Pryor, J., & Westbrook, J. (2013). Improving teaching and learning of basic maths and reading in Africa: Does teacher preparation count? International Journal of Educational Development, 33, 272-282. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2012.09.006

Allas, R. Leijen, Ä, & Toom, A. (2020). Guided reflection procedure as a method to facilitate student teachers’ perception of their teaching to support the construction of practical knowledge. Teachers and Teaching. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2020.17580

Barton, K., & Levstik, L. S. (2010). Why don’t more history teachers engage students in interpretation? In W. C. Parker (Ed.), Social Studies Today: Research and Practice (pp. 35-42). Routledge.

Barnes, A. E., Zuilkowski, S. S., Mekonnen, D., & Ramos-Mattouss, F. (2018). Improving teacher training in Ethiopia: Shifting the content and approach of pre-service teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 70, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.11.004

Bassot, B. (2016). The Reflective Practice Guide: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Critical Reflection. Routledge.

Beauchamp, C. (2015). Reflection in teacher education: issues emerging from a review of current literature. Reflective Practice, 16(1), 123-141. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2014.982525

Berry, A. (2008). Tensions in teaching about teaching: Understanding practice as a teacher educator. Springer.

Boud, D., & Walker, D. (1998). Promoting reflection in professional courses: The challenge of context. Studies in Higher Education, 23(2), 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079812331380384

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063o

Bremner, N., Sakata, N., & Cameron, L. (2023). Teacher education as an enabler or constraint of learner-centred pedagogy implementation in low-to middle-income countries. Teaching and Teacher Education, 126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104033

Bullock, S. M., & Ritter, J. K. (2011). Exploring the Transition into Academia through Collaborative Self-Study. Studying Teacher Education, 7(2), 171-181. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425964.2011.591173

Cuenca, A. (2020). Ethics of self-study research as a legitimate methodological tradition. In J. Kitchen, A. Berry, S. M. Bullock, A. R. Crowe, M. Taylor, H. Guðjónsdóttir, & L. Thomas (Eds.), International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices (2nd ed.) (pp. 461–482). Springer.

Demoz, B. (2021). Lesson planning: A pedagogic scholarship process. [Unpublished manuscript]

Demoz, B. (2011). Initial Teacher Education for Elementary School Teachers in Eritrea: practice and policy. Doctoral thesis, Euclid University.

Fletcher, T. (2020). Self-Study as Hybrid Methodology. In J. Kitchen, A. Berry, S. M. Bullock, A. R. Crowe, M. Taylor, H. Guðjónsdóttir, & L. Thomas (Eds.), International Handbook of Self-Study of Teaching and Teacher Education Practices (2nd ed.) (pp. 269-297). Springer.

Fletcher, T., Ní Chróinín, D., & O’Sillivan, M. (2016). A layered Approach to critical friendship as a means to support innovation in pre-service teacher education. Studying Teacher Education, 12(3), 302-319. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425964.2016.1228049

Glasswell, K., & Ryan, J. (2017). Reflective Practice in Teacher Professional Standards: Reflection as Mandatory Practice. In R. Brandenburg, K. Glasswell, M. Jones, & J. Ryan (Eds.), Reflective Theory and Practice in Teacher Education (pp. 2-26). Springer.

Hailemariam, C., Ogbay, S., & White, G. (2010). The Development of Teacher Education in Eritrea. In G. Karras, & C. C. Wolhuter (Eds.), International Handbook of Teacher Education World-wide: Issues and Challenges (pp. 701–736). Atrapos Editions.

Harber, C. (2012). Contradictions in teacher education and teacher professionalism in Sub-Saharan Africa: the case of South Africa. In R. Griffin (Ed.), Teacher education in Sub-Saharan Africa: Closer perspectives (pp. 55-70). Symposium Books Ltd.

Idris, K. M. (2023). Tensions of Embedding Reflective Teaching Practices in Teacher Education in Eritrea: A Self-Study on Facilitation Experiences. Studying Teacher Education, 19(3), 251-270. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425964.2023.2202012

Idris, K., Eskender, S., Demoz, B., Yosief, A., & Andemicael, K. (2021). ‘Let’s focus on us’: Recounting educators’ facilitation practices in improving collaborative commitments of learner-teachers during an action research course. Educational Action Research, 31(4), 797-820. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2021.2000877

Idris, K. M., Posti-Ahokas, H., & Lehtomäki, E. (Forthcoming). Developing a teaching-research nexus in teacher education: Recounts of an educator’s self-study. Teaching in Higher Education.

Isotalo, S. (2017). Teacher Educators’ Professional Identity Formation in a Challenging Context: Experience from Eritrea. Master’s Thesis in Education. University of Jyväskylä.

James, F., & Augustin, D. S. (2018). Improving teachers’ pedagogical and instructional practice through action research: potential and problems. Educational Action Research, 26(2), 333-348. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2017.1332655

Kemmis, S. (2022). Transforming practices: Changing the world with the theory of practice architectures. Springer.

Korthagen, F. A. (2016). Pedagogy of Teacher Education. In J. Loughran, & M. L. Hamilton (Eds.), International Handbook of Teacher Education (pp.311-346). Springer.

Korthagen, F. A. (2017). Inconvenient truths about teacher learning: towards professional development 3.0. Teachers and Teaching, 23(4), 387-405. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1211523

LaBoskey, V. K. (2004). The methodology of self-study and its theoretical underpinnings. In J. J. Loughran, M. L. Hamilton, V. L. Laboskey, & T. Russell (Eds.), International Handbook of Self-Study of teaching and teacher education practices (pp. 817-869). Springer.

Loughran, J. (2019). Pedagogical reasoning: the foundation of the professional knowledge of teaching. Teachers and Teaching, 25(5), 523-535. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2019.1633294

Loughran, J. & Berry, A. (2005). Modelling by teacher educators. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(2), 193-203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2004.12.005

Loughran, J. (2014). Professionally Developing as a Teacher Educator. Journal of Teacher Education, 65(4), 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487114533386

Marshall, T. (2019). The concept of reflection: a systematic review and thematic synthesis across professional contexts. Reflective Practice, 20(3), 396-415. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2019.1622520

Mayumbelo, C., & Nyambe, J. (1999). Critical Inquiry into Preservice Teacher Education: Some Initial Steps Toward Critical, Inquiring, and Reflective Professionals in Namibian Teacher Education. In Democratic teacher education reform in Africa. (pp. 64-81). Routledge.

McCool, M. & Myers, J. (2021). Reviewing the literature to clarify self-study research. Educational Action Research, 31(3), 472-489. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2021.1976660

MacPhail, A., Ulvik, M., Guberman, A. Czerniawski, G., Oolbekkink-Marchand, H., & Bain, Y. (2019). The professional development of higher education-based teacher educators: needs and realities. Professional Development in Education, 45(5). https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2018.1529610

Malm, B. (2020). On the complexities of educating student teachers: teacher educators’ views on contemporary challenges to their profession. Journal of Education for Teaching (46)3, 351-364. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2020.1739514

Nguyen, N. T. (2023) How to develop four competencies for teacher educators. Frontiers in Education, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1147143

O’Sullivan, M. C. (2010). Educating the teacher educator: A Ugandan case study. International Journal of Educational Development, 30, 377–387. http://doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2009.12.005

Ping, C., Schellings, G., & Beijaard, D. (2018). Teacher Educators’ Professional Learning: A Literature Review. Teaching and Teacher Education, 75, 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.06.003

Pithouse-Morgan, K. (2022). Self-study in Teaching and Teacher Education: Characteristics and contributions. Teaching and Teacher Education, 117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103880

Posti-Ahokas, H., Idris, K., Hassen, M., & Isotalo, S. (2021). Collaborative professional practices for strengthening teacher educator identities in Eritrea. Journal of Education for Teaching, 48(3), 300–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2021.1994838

Raelin, J. A. (2007). Towards an Epistemology of Practice. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 6(4), 495–519. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2007.27694950

Ritter, J. K., & Quiñones, S. (2020). Entry points for self-study: Where to begin. In J. Kitchen, A. Berry, S. M. Bullock, A. R. Crowe, M. Taylor, H. Guðjónsdóttir, & L. Thomas (Eds.), International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices (2nd ed.) (pp. 339–375). Springer.

Rodgers, C. R., & Raider-Roth, M. (2006). Presence in teaching. Teachers and Teaching: theory and practice, 12(3), 265-287. https://doi.org/10.1080/13450600500467548

Russell, T. (2013). Has Reflective Practice Done More Harm than Good in Teacher Education? Phronesis, 2(1), 80–88. https://doi.org/10.7202/1015641ar

Schweisfurth, M. (2011). Learner-centred education in developing country contexts: From solution to problem? International Journal of Educational Development, 31(5), 425-432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2011.03.005

Senese, J. C. (2017). How Do I Know What I Think I Know? Teaching Reflection to Improve Practice. In R. Brandenburg, K. Glasswell, M. Jones, & J. Ryan (Eds.), Reflective Theory and Practice in Teacher Education (pp. 103–117). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3431-2_6

Stutchbury, K. (2019). Teacher educators as agents of change? A critical realist study of a group of teacher educators in a Kenyan University. EdD thesis, The Open University.

Tadesse, T., Lehesvuori, S. Posti-Ahokas. H., & Moate, J. (2023). The learner-centred interactive pedagogy classroom: Its implications for dialogic interaction in Eritrean secondary schools. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2023.101379

Tao, S. (2013). Why are teachers absent? Utilising the Capability Approach and Critical Realism to explain teacher performance in Tanzania. International Journal of Educational Development, 33, 2-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2012.01.003

Van Beveren, L., Roets, G., Buysse, A., & Rutten, K. (2018). We all reflect, but why? A systematic review of the purposes of reflection in higher education in social and behavioral sciences. Educational Research Review, 24, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.01.002

Vanassche, E. (2022). Four propositions on how to conceptualize, research, and develop teacher educator professionalism. Frontiers in Education, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.1036949

Vanassche, E., & Berry, A. (2020). Teacher Educator Knowledge, Practice, and S-STTEP Research. In J. Kitchen, A. Berry, S. M. Bullock, A. R. Crowe, M. Taylor, H. Guðjónsdóttir, & L. Thomas (Eds.), International Handbook of Self-Study of Teaching and Teacher Education Practices (2nd ed.) (pp. 177-213). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6880-6_6

Vanassche, E., Kelchtermans, G.,Vanderlinde, R., & Smith, K. (2021). A conceptual model of teacher educator development: An agenda for future research and practice. In R. Vanderlinde, K. Smith, J. Murray, & M. Lunenberg (Eds.), Teacher Educators and their Professional Development: Learning from the Past, Looking to the Future (pp. 15-27). Routledge.

Vavrus, F., Thomas, M., & Bartlett, L. (2011). Ensuring quality by attending to inquiry: Learner-centred pedagogy in sub-Saharan Africa. UNESCO CBA International Institute for Capacity Building in Africa.

Westbrook, J., Durrani, N., Brown, R., Orr, D., Pryor, J., Boddy, J., & Salvi, F. (2013). Pedagogy, Curriculum, Teaching Practices and Teacher Education in Developing Countries. Final report. Education rigorous literature review. EPPI–Centre.

Worku, M. Y. (2017). Improving primary school practice and school–college linkage in Ethiopia through collaborative action research. Educational Action Research, 25(5), 737-754. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2016.1267656

Zeichner, K. M. & Liston, D. P. (2014). Reflective teaching: An introduction. (2nd ed.). Routledge.