Vol 7, No 2 (2023)

https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.5392

Article

Culturally responsive assessment in compulsory schooling in Denmark and Iceland – An illusion or a reality? A comparative study of student teachers’ experiences and perspectives

Artëm Ingmar Benediktsson

Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences

Email: artem.benediktsson@inn.no

Abstract

This paper explores and compares student teachers’ experiences and perspectives on culturally responsive assessment in compulsory schooling in Denmark and Iceland. The study’s theoretical framework draws on scholarship on culturally responsive assessment. The data was derived from fourteen interviews with Danish student teachers and ten interviews with Icelandic student teachers. As per the selection criteria, all participants had to be in the final stages of their education process, meaning they had completed their on-site schoolteacher training and most courses in their teacher education programme. During the interviews, the participants reflected on pre-instructional, formative, and summative assessment practices with cultural diversity in mind. Furthermore, they discussed the importance of assessing children’s well-being. In both countries, the participants demonstrated positive attitudes towards cultural diversity and expressed awareness of considering children’s cultural and linguistic backgrounds when assessing them. On the other hand, most participants expressed criticism of their teacher education programmes for lacking attention to the topic of culturally responsive assessment, which resulted in their rudimentary understanding of the theoretical underpinnings.

Keywords: multicultural education, cultural diversity, teacher education, on-site training, qualitative study

Introduction

Increased cultural and linguistic diversity in compulsory schools in Denmark and Iceland created many opportunities for all educational stakeholders. Cultural diversity may enhance pupils’ and teachers’ multicultural competence, potentially reducing existing prejudice and establishing an empowering school environment (e.g., Grapin et al., 2019; Vervaet et al., 2018). However, there remain challenges which, for instance, manifest in Danish and Icelandic school personnel lacking theoretical and practical knowledge of teaching and assessment methods suitable for pupils from diverse cultural backgrounds (Daníelsdóttir & Skogland, 2018; Frederiksen et al., 2022; Mock-Muñoz de Luna et al., 2020). Therefore, higher education institutions are responsible for responding to the changing demographics of pupil populations in compulsory schools by enhancing teacher education programmes. This necessitates providing comprehensive support and training to future school personnel, particularly teachers, to enable them to successfully work with and support cultural diversity within their classrooms.

Within educational research and theory, there is a notable disparity in the attention given to teaching methods compared to the discussion of assessment. This paper puts a spotlight on assessment by presenting the findings that delve into the experiences and perspectives of student teachers regarding culturally responsive assessment practices in the context of compulsory schooling in Denmark and Iceland. The guiding research questions are: What are the perspectives and experiences of student teachers regarding the implementation of assessment practices that are suitable for children from diverse cultural backgrounds? What are the similarities and differences in the participants’ perspectives between Denmark and Iceland? How do Danish and Icelandic student teachers perceive the support and training provided by their respective teacher education programmes in preparing them for utilising culturally responsive assessment? The paper addresses the research questions by conducting a comprehensive analysis of individual interviews with Danish and Icelandic student teachers, who were asked to reflect on pre-instructional, formative, and summative assessment practices, all within the context of considering pupils’ cultural diversity.

Although, as previously mentioned, there is a lack of research on culturally responsive assessment in Denmark and Iceland, several recent studies touched upon the significance of applying appropriate practices to assess children from diverse cultural backgrounds. For instance, a case study by Frederiksen et al. (2022), conducted with ethnic minority boys in a Danish public school, revealed that teaching and assessment practices predominantly reflected an assimilation-oriented monocultural mindset, portraying cultural backgrounds of ethnic minority children in generalised terms and focusing on knowledge deficiencies, while Danish culture was presented as the underlying norm. A comparative study by Mock-Muñoz de Luna et al. (2020) reported a lack of appropriate assessment practices within schools to evaluate the educational needs of newly arrived migrant and refugee children in Denmark. Schools were given screening reports obtained from a municipal standardised pre-instructional assessment, which, according to the participants of the study, shifted focus from a deficit-based approach to one emphasising children’s strengths, abilities, and previous knowledge (Mock-Muñoz de Luna et al., 2020). However, school personnel also highlighted that the reports were lengthy, inconsistent in quality, and, therefore, not always useful (Mock-Muñoz de Luna et al., 2020).

In Iceland, an action research study conducted by Gústafsdóttir and Sigurðardóttir (2020) explored assessment practices of learning and well-being of children with diverse cultural backgrounds. The study revealed a significant need for enhanced professional development opportunities for preschool personnel in the domains of culturally responsive assessment (Gústafsdóttir & Sigurðardóttir, 2020). Daníelsdóttir and Skogland (2018) reported that the results of PISA tests indicated that the reading comprehension skills of children with Icelandic as the second language are far from satisfactory and are deteriorating, which is a serious concern since these children also face difficulties in their overall academic progress in other subjects. However, Daníelsdóttir and Skogland (2018) recognise that it is inaccurate to solely attribute the lower results in PISA tests to children’s linguistic competencies, and there is a demand for the development of improved assessment practices that can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing these children’s performance. A literature review analysis conducted by Nortvedt et al. (2020) argued that lower PISA test results could be attributed to either variation in the preparedness of schools and teachers to address cultural diversity or systemic issues in the quality of educational services offered to children with diverse cultural backgrounds.

By delving into the reflections and experiences of Danish and Icelandic student teachers, the study presented in this paper contributes to the existing literature on culturally responsive assessment. It provides valuable insights for teacher education programmes and educational policymakers seeking to enhance school personnel’s theoretical and practical knowledge of successful assessment practices, applied with children’s cultural diversity in mind. The following section will introduce a conceptual exploration of the tenets of culturally responsive assessment, which form the foundation of the study’s theoretical framework.

Culturally responsive assessment

The theoretical framework of this study draws on the tenets of culturally responsive assessment, which derives from the scholarship on multicultural education and culturally responsive teaching (Gay, 2000; Ladson-Billings, 2021; Nieto, 2010). Culturally responsive teaching is a learner-centred approach that acknowledges and values various cultural experiences and perspectives through integrating culturally diverse content, utilising teaching practices that reflect students’ cultural backgrounds, and fostering positive relationships between teachers and students based on mutual respect and trust (Gay, 2000).

When it comes to assessing learners from diverse cultural backgrounds, various challenges have been identified, including issues of achievement standards, biased assessment practices, and the overall unpreparedness of schools and teachers to address cultural diversity (Nortvedt et al., 2020). Since these issues are interconnected, holistic and learner-centred classrooms that recognise and value diversity must be established, enabling appropriate assessment of learners with diverse cultural backgrounds (Nortvedt et al., 2020). Utilising a holistic view of assessment is necessary to avoid deficit-based judgments and gain a comprehensive understanding of every learner’s unique needs. Kirova and Hennig (2013) argue that it is also crucial to reflect on whose expectations are considered in assessment, challenge dominant discourses which categorise children based on standardised criteria and emphasise the relational nature of power in assessment practices. Culturally responsive assessment accommodates and validates different cultural perspectives, diverse ways of knowing, and forms of participation within multicultural classrooms (Kirova & Hennig, 2013; Nortvedt et al., 2020). Furthermore, culturally responsive assessment focuses intently on evaluating learners’ well-being, requiring a comprehensive understanding of how it intersects with academic achievement (Borsato & Padilla, 2008; Kirova & Hennig, 2013; Padilla & Borsato, 2008). Well-being and its assessment are recognised as a multifaceted process that encompasses the evaluation of physical health, mental and emotional wellness, social connectedness, and a sense of belonging within a cultural context (Berry & Hou, 2017; Hargreaves, 2003; Gústafsdóttir & Sigurðardóttir, 2020; Padilla & Borsato, 2008).

Given these complexities in culturally responsive assessment practices, the pursuit of validity emerges as a crucial aspect of assessment quality (Padilla & Borsato, 2008). Validity in assessment refers to the soundness of the interpretations, ensuring that the assessment is aligned with the intended learning objectives and provides meaningful and relevant information about the knowledge, skills, or abilities being assessed (Brookhart & Nitko, 2019). Therefore, teachers are responsible for being mindful of potential biases in assessing children from diverse cultural backgrounds (Padilla & Borsato, 2008). Specifically, they should critically examine whether assessment tasks and materials reinforce cultural, racial, or gender-based stereotypes (Brookhart & Nitko, 2019). This applies to all types of assessment, including pre-instructional, formative, and summative assessments. The purpose of pre-instructional assessment is to collect information regarding pupils’ prior knowledge, enabling the planning of customised teaching that addresses the specific needs of each learner (Brookhart & Nitko, 2019). Formative assessment is a continuous process that involves gathering information and providing constructive feedback to pupils, aiming at advancing their learning by identifying strengths and areas requiring improvement (Brookhart & Nitko, 2019). On the other hand, summative assessment is typically conducted at the end of a course to evaluate learning outcomes and assign grades or judgments of achievement (Brookhart & Nitko, 2019).

To ensure fair and culturally responsive assessment, teachers must strive for increased cultural competence, which implies a reflection on equity issues by developing awareness of social, economic, structural, or other inequalities between the pupils in their classrooms (Gay, 2000; Nortvedt et al., 2020; Padilla & Borsato, 2008). However, it is important to note that adjusting assessment practices for learners from diverse cultural backgrounds should not be equated with lowering standards and expectations, as it may negatively impact their self-image and perpetuate their marginalisation within educational settings (Brookhart & Nitko, 2019; Gay, 2000). Instead, teachers should reflect on equity issues, especially in norm-referenced tests, which are commonly used to compare an individual’s test score to that of a norming group. Padilla and Borsato (2008) argue that the validity of such tests becomes uncertain when administered to individuals whose cultural or linguistic backgrounds were not adequately represented in the norming group.

There is a common misconception that minority learners’ high levels of proficiency in the language of instruction automatically lead to their higher academic achievement (Borsato & Padilla, 2008; Herzog-Punzenberger et al., 2020). According to findings from a comparative study conducted in four European countries by Herzog-Punzenberger et al. (2020), teachers’ perception of diversity in classrooms was primarily based on proficiency in the language of instruction, with less emphasis on the cultural dimension. The teachers made efforts to adapt assessment and grading practices to support students from diverse cultural backgrounds, but these initiatives were often unstructured and derived from their own assumptions and observations (Herzog-Punzenberger et al., 2020). Padilla and Borsato (2008) shed light on the practice of translating assessment tasks and materials as a measure to enhance equity by facilitating pupils’ understanding and engagement with the assessment content. Translating assessment materials requires more than being fluent in both languages. A translator must possess comprehensive knowledge of the cultures involved, the content being assessed, and the intended purposes of the assessment. Furthermore, pilot testing of the materials is necessary, followed by standardisation of grades and validation research (Padilla & Borsato, 2008). Appropriate translation can be challenging, time-consuming, and costly, and therefore not widely considered to be a sufficient solution to address the issue of equity in assessment (Padilla & Borsato, 2008).

Instead of aiming at conducting a complex task of translating assessment materials, teachers may explore other ways to enhance their clarity and accessibility. These may include modifying unfamiliar terms to ones that are well-known and frequently used, changing passive verb forms to active, shortening lengthy word groups and sentences, simplifying complex question phrases, and rewording descriptions using more definitive language (Frisby, 2008). Furthermore, teachers may explore other ways of assessing children from diverse cultural backgrounds, such as through interviews or visual narratives (Kirova & Hennig, 2013). An example of visual narratives can be language portraits, which are created by children by using a visual representation, such as a body silhouette that is painted with different colours and decorated with symbols or labels to identify each language (Busch, 2012; Dressler, 2014). Language portraits can be valuable in educational settings to recognise and validate children’s languages and identities, as well as they can be used as a way to assess children’s language repertoires (Busch, 2012; Dressler, 2014).

In summary, culturally responsive assessment refers to a holistic learner-centred approach to evaluating learners from diverse cultural backgrounds, sensitive to their cultural backgrounds, experiences, and educational contexts (Kirova & Hennig, 2013; Nortvedt et al., 2020). To apply culturally responsive assessment, school personnel need to obtain appropriate knowledge and receive training with a focus on developing cultural competence (Frisby, 2008; Gústafsdóttir & Sigurðardóttir, 2020; Padilla & Borsato, 2008). Hence, research within higher education institutions plays a significant role in examining the position of culturally responsive assessment in teacher education programmes, as well as gaining insights into student teachers’ theoretical and practical knowledge thereof.

Given the comparative nature of the current study, it is crucial to consider its contextual background (Bray et al., 2007; Fairbrother, 2007). Hence, the following section provides concise contextual information about teacher education in Denmark and Iceland, offering a foundation for understanding the subsequent methodology and study findings.

Teacher education in Denmark and Iceland

Teacher education in Denmark is offered by six university colleges, which have campuses across the country. In the current Danish education system, attaining professional teacher status requires candidates to engage in a comprehensive four-year programme comprising coursework and on-site training, amounting to 240 ECTS credits (Danske professionshøjskoler, 2022). Candidates with previous educational and professional experience are given the opportunity to expedite their path to becoming professional teachers through the Merit-Teacher Training Programme. Successful completion of teacher education leads to acquiring a Bachelor’s Degree in Education, recognised at level six on the European Qualifications Framework (Ministry of Higher Education and Science (Denmark), n.d.). The teacher education programme in Denmark follows a highly structured curriculum that is largely predetermined by the Ministry of Higher Education and Science. The programme consists of compulsory and elective modules, with students required to select three school subjects as their specialisations. Multicultural perspectives are currently included in a module on teaching Danish as a second language (5 ECTS credits), which is a part of teacher’s fundamental expertise and, therefore, mandatory for all students. The purpose of the module is to equip students with the necessary skills to work with children with diverse linguistic backgrounds, which includes planning, implementing, and evaluating Danish as a second language instruction based on the children’s overall linguistic repertoires (Ministry of Higher Education and Science (Denmark), 2023). Additionally, students have the option to choose Danish as a second language (35 ECTS credits) as one of their specialisations, enabling a more in-depth exploration of this topic. Multicultural perspectives are also integrated into modules on teaching foreign languages, such as English or German, assuming that students choose these as specialisations. The on-site schoolteacher training is mandatory, and at the time of the study, it accounted for 30 ECTS credits. However, recent regulatory changes have increased the required training hours within the programme, which now account for 40 ECTS credits (Ministry of Higher Education and Science (Denmark), 2022). These amendments reflect a recognition of the significance and value of practical training experiences in shaping the professional development of future teachers.

Teacher education in Iceland is offered by the University of Iceland and the University of Akureyri, which have a variety of programmes to prepare teachers to work at all school levels – preschool, compulsory and upper secondary. Additionally, Reykjavík University offers a sports teacher education programme, and the Iceland University of the Arts offers arts teacher education. In the current Icelandic education system, attaining professional teacher status requires the completion of a Master’s Degree in Education or its equivalent officially approved by the Icelandic Directorate of Education. An integrated five-year teacher education programme consists of a three-year Bachelor’s Degree (180 ECTS credits) and a two-year Master’s Degree (120 ECTS credits), placing Icelandic teacher education at level seven on the European Qualifications Framework (Ministry of Education, Science and Culture (Iceland), 2014). Icelandic universities have considerable flexibility in designing and organising teacher education, as the legislation provides broad goals and expectations without specifying the curriculum in detail (Teacher Education Act (Iceland), 2019). Consequently, teacher education programmes exhibit substantial variation across universities and even within the same university, as, for instance, the University of Iceland offers dozens of teacher education programmes with various specialisations, such as teaching young children, inclusive special education, language teaching (Icelandic, English, Danish), sports education, home economics, and others. Multicultural perspectives are included as either mandatory or elective subjects depending on the chosen specialisation, typically encompassing no more than 15 ECTS credits. Similar to the Danish educational context, multicultural perspectives are also integrated into courses on teaching foreign languages, assuming that students choose these as specialisations. On-site schoolteacher training is a mandatory component across all specialisations, albeit with variations in its extent. The scope of training ranges from approximately 30 to 40 ECTS fieldwork credits within the integrated five-year programmes.

Methodology

The current study adopts a qualitative research design, employing individual interviews as the primary method for data collection. The selection of a qualitative methodology stems from the main objective of gaining a comprehensive understanding of participants’ opinions and experiences. Furthermore, qualitative research design provides flexibility and adaptability in the exploration of emergent themes and unexpected findings (Braun & Clarke, 2013). The study is a comparative project which aims at comparing teacher education in Denmark and Iceland, with a special focus on investigating the extent to which the topic of culturally responsive assessment is incorporated into the respective programmes. The study also compares Danish and Icelandic student teachers’ theoretical and practical knowledge of assessment practices suitable for children from diverse cultural backgrounds.

In Denmark, data were collected at three university colleges located in different regions of the country. In Iceland, data collection took place at two universities located in different regions of the country. The participants were fourteen Danish and ten Icelandic student teachers. At the time of the study, they were nearing completion of their educational journey through teacher education. According to the selection criteria, all participants had to be in the final year of their studies and have completed on-site schoolteacher training and most courses included in their programme. In addition to receiving on-site training, all participants had work experience lasting from several months to over a decade in compulsory education institutions in their respective countries. The average age of the participants was 26 years old in Denmark and 39 years old in Iceland. There is an age difference between the participants in the study, as the selection criteria did not specify age; therefore, students of all ages were welcome to participate. In Denmark, the age variation ranged from 24 to 32 years old. In Iceland, the age variation was notably larger, ranging from 26 to 56 years old. This diversity in age is considered a strength of the study, not aiming for generalisation but rather seeking to elicit a breadth of opinions from the participants who represent various experiences and social backgrounds. The participants had different specialisations within their programmes, such as teaching mathematics, inclusive special education, foreign language teaching, and others. All these programmes were specifically tailored to prepare the students for future careers in compulsory education in their respective countries. In both Denmark and Iceland, compulsory education refers to a unified system encompassing primary and lower secondary education [da. folkeskole, ís. grunnskóli]. Over a period of 10 years, this educational system is designed to educate children, generally within the age range of 6 to 16 years old. The participants’ specialisations and work experience are revealed, where relevant, in the findings section.

In both countries, the participants were recruited with the help of teacher educators at participating universities and university colleges. The researcher initiated contact with the teacher educators, providing them with comprehensive information about the study. Subsequently, a series of online meetings were organised with several teacher educators, throughout which the researcher elucidated the study’s background and objectives. During the meetings, the teacher educators offered valuable insights into the structures of teacher education programmes at their institutions, facilitating the researcher’s contextual understanding. Following this, the teacher educators sent letters of invitation to potential participants. The students who showed interest in participating received a participant information sheet, including a comprehensive project description. Privacy considerations adhered to national and European data protection regulations, emphasising the voluntary nature of participation in the project and granting participants the freedom to withdraw at any time without providing any explanation. Informed consent was collected from all participants, who, by signing the form, agreed to be audio recorded during the interviews. The interviews were conducted in Danish and Icelandic, respectively.

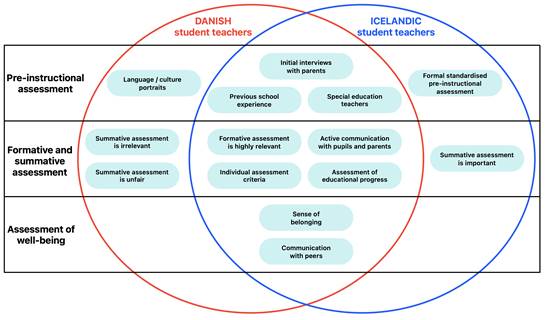

The analytical process of this study consisted of two distinct phases: thematic analysis and comparative analysis. Atlas.ti analytical software was used throughout the project. Initially, the interview transcriptions were subjected to close reading to gain a comprehensive understanding of the content. Thematic analysis followed the framework outlined by Braun and Clarke (2013), involving a full coding approach with both researcher-derived and data-derived codes. Researcher-derived codes were determined based on the literature review, while data-derived codes emerged naturally during the coding process and captured unforeseen topics. Upon completion of coding, a thorough examination of the codebook was conducted, consisting of interconnecting, merging, and omitting codes when needed. The codes were then organised into distinct categories based on their meanings, which evolved into themes. The comparative analysis phase included a visualisation of thematic patterns by constructing code networks for each participant group, specifically student teachers from Denmark and Iceland. These code networks were later compared and overlaid to identify similarities and differences in the findings between the two groups. The outcomes of the analytical process are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Perspectives and experiences of student teachers regarding the implementation of assessment practices suitable for children from diverse cultural backgrounds.

The researcher took responsibility for translating the interview quotations featured in the findings section, aiming to maintain their fidelity to the original language. An assistant familiar with both languages and cultures was involved to ensure a balance between grammatical accuracy and meaning. Attention was paid to avoid potential biases or misinterpretations, guided by the awareness that translation is an interpretative act. The original Danish and Icelandic quotations can be provided upon request.

Findings

This section explores the findings obtained from the interviews with student teachers in Denmark and Iceland. The findings are organised into three subsections, each focusing on the participants’ perspectives regarding pre-instructional assessment, formative and summative assessment, and the assessment of children’s well-being. Pseudonyms are used throughout to refer to the participants.

Pre-instructional assessment

During the interviews, the participants were asked to reflect on different forms of assessment of children from diverse cultural backgrounds. Their reflections were based upon their acquired theoretical knowledge from teacher education programmes, as well as their practical experiences gained through on-site training and work in public schools. In both Denmark and Iceland, none of the participants possessed a comprehensive understanding of assessment practices for children from diverse cultural backgrounds, indicating that this topic received limited attention in their respective teacher education programmes. Participants expressed a desire for greater knowledge and preparedness in this area to successfully work with culturally diverse pupils in their future teaching careers. Despite the limited emphasis on the topic within universities and university colleges, many participants were able to acquire some knowledge and general ideas about assessing this group of pupils. Through on-site training and previous experience in public schools, the participants gained practical insights into working with children from diverse cultural backgrounds. This suggested that practical experiences played a significant role in shaping their understanding of various assessment practices.

Pre-instructional assessment was a prominent subject in the interviews conducted in both countries. The participants shared diverse perspectives and experiences regarding the reception of newly arrived children and their subsequent assessment. The analysis of the interviews revealed variations in reception strategies between the countries and within them, encompassing differences across individual municipalities and schools. To elucidate these variations, it is important to consider the existing legislation about the reception of newly arrived immigrant children in compulsory education. In Denmark, an executive order on teaching Danish as a second language published by the Ministry of Children and Education (2016) provides a somewhat ambiguous description of the reception strategies for newly arrived children. This description allows for different interpretations and applications, stating that newly arrived children who require language support are entitled to receive basic instruction in Danish through various methods, including reception classes, special groups, or individual teaching. Similarly, in Iceland, the Education Act (2008) mandates schools to follow either their own reception plan or the municipality’s reception plan. It also emphasises the importance of establishing positive collaboration with parents during the reception period. In both countries, individual schools are responsible for evaluating the circumstances and providing children with the necessary language instruction tailored to their specific needs as identified through the assessment.

Hence, the participants in both Denmark and Iceland emphasised the significance of conducting initial interviews with parents. These interviews were described as a part of the pre-instructional assessment and had two main purposes: first, to gather information about the life and educational experiences of newly arrived children, and second, to establish a connection with the families. The participants expressed a preference for conducting these interviews themselves without the need for an interpreter. Based on their previous work experience, most parents from diverse cultural backgrounds were able to communicate in English. Additionally, some participants also reported utilising other languages available in their language repertoires. Only when a common language could not be found would they seek assistance from colleagues, with hiring an interpreter being considered a last resort, not least due to the associated high costs. The participants in both countries also highlighted the importance of direct communication with children to understand their previous experiences. For instance, Dorit, a participant from Denmark who specialises in teaching mathematics, shared her experience of conducting an initial interview with a newly arrived pupil.

It was more about getting to know, well, what kind of person this child was. What did [they] do at school before? What kind of schooling [were they] used to? Because we were pretty sure that going to school in [their country] is not the same as going to school in Denmark. We spent the most time on that. There was nothing professional about it, but more like an exploration of what kind of person we had here. (Dorit)

The provided quotation from Dorit’s interview highlights a common trend among the participants, wherein they expressed a lack of theoretical knowledge concerning pre-instructional assessment practices. The participants shared that they were advised to seek assistance from special education teachers within schools or municipal educational offices when assessing newly arrived pupils. This indicates a potential gap in the teacher education programmes, which fostered a reliance on external support services instead of equipping student teachers with the necessary knowledge and skills to conduct pre-instructional assessments independently.

The participants in Iceland mentioned a formal standardised pre-assessment framework that they called the ‘Swedish’ assessment [ís. sænska matið]. They revealed that this framework was presented in their teacher education programme. Furthermore, it is well known and widely used in public schools. Ísbjörg, who specialises in primary education and has years of experience in public schools in Iceland, provided insights into the assessment procedures of newly arrived pupils at her school.

There is often a reception interview. We may have an interpreter with us. And we go through... how our school system works and what our school is like. And then, we inquire about the pupil’s knowledge, and sometimes we apply the so-called ‘Swedish’ assessment. I know it was done in our school. There was a person from the municipality who came to assess the children. And then we just have to evaluate – ok, they did well in mathematics – then I can give them the same learning materials as the other kids. (Ísbjörg)

In Icelandic schools, the term ‘Swedish’ assessment is used to describe a framework that draws upon a range of documents and assessment practices developed by the Swedish National Agency for Education. These documents have been adapted and contextualised by the Icelandic Directorate of Education to meet the needs of the Icelandic educational system, resulting in a comprehensive framework for conducting pre-instructional assessments of newly arrived children (Directorate of Education (Iceland), 2016). The ‘Swedish’ assessment encompasses a structured process comprised of three distinct phases: 1. Language assessment and evaluation of prior experiences; 2. Assessment of literacy and numeracy skills; and 3. Subject-specific assessment. The assessment requires a team of professionals involving a schoolteacher, a specialist from municipal support services, an interpreter, and, in certain instances, a special education teacher. In most cases, the assessment is administered in the child’s strongest language (Directorate of Education (Iceland), 2016). Ísabella’s specialisation is inclusive special education. While reflecting on her experiences of conducting the ‘Swedish’ assessment, she expressed a sense of amazement at the level of mastery demonstrated by the child when the assessment tasks were administered in their strongest language.

I observed a pupil who was taking mathematics. It was amazing to see [them] with [their] own language. I did not understand anything – it was Arabic. I thought it was really great that this was possible. And I think this is something I know far too little about. (Ísabella)

Several participants in Denmark mentioned the use of language portraits as a method for conducting pre-instructional assessments of newly arrived children. They perceived language portraits as a dynamic and engaging approach that facilitates the exploration of children’s linguistic backgrounds and establishes meaningful connections with them. One participant, Dicte, who specialises in teaching English, expressed a desire to extend this practice by encouraging children to create culture portraits, which would provide valuable insights into their cultural backgrounds.

I definitely want to work with narratives – how you portray others and how you portray yourself. And maybe something like language portraits. And I think you can also make culture portraits, so you can talk about what it means to you and such... And then show them to everyone. I also think it gives you a lot and you can understand yourself a little better. (Dicte)

In summary, the Danish and Icelandic participants could come up with some interesting examples of assessment practices that can be considered, to some extent, as culturally responsive. However, they had limited theoretical knowledge of culturally responsive pre-instructional assessment practices. The following subsection focuses on their experiences and reflections regarding formative and summative assessment practices applied with cultural diversity in mind.

Formative and summative assessment

When it comes to formative and summative assessment suitable for children from diverse cultural backgrounds, most participants acknowledged again that they had very limited knowledge on this topic, primarily due to the lack of attention to it within their respective teacher education programmes. For instance, a quotation from the interview with Íris, who specialises in primary education in Iceland, exemplifies the typical response among participants in both countries.

Wow! I don't know. I don't know how you do it. I haven't heard this before, but I still think I might try to assess their development first and foremost. So maybe to take into consideration their experience and knowledge, but I don't know. I would really need help with the assessment. I am not an expert, and I have not done it before. (Íris)

Although the participants possessed limited theoretical knowledge of the topic, they were able to present various examples of assessment practices derived from their field experiences. Formative assessment practices included ongoing quizzes, in-class group assignments, and portfolios, while summative practices mainly consisted of tests and essays. The alignment of these examples with the principles of culturally responsive assessment varied, yet participants articulated an awareness of the need to take children’s linguistic competencies into account and, to a lesser extent, consider children’s cultural backgrounds. This awareness was demonstrated, for example, by simplifying the language of assignments, providing translations, permitting children to work in pairs, or in some instances, allowing the use of translation software.

Most participants in both countries considered formative assessment highly relevant, emphasising its ability to facilitate timely adjustments in teaching practices and offer valuable feedback to students and parents. However, the participants primarily focused on identifying areas of weakness, particularly concerning language proficiency in Danish and Icelandic, respectively. The improvement of language skills emerged as a predominant objective of formative assessment, as described by the participants. While many participants expressed their attempts to develop individual assessment criteria for formative assessment tailored to each pupil’s diverse needs and prior knowledge, they were unable to provide concrete examples of a systematic approach for determining such criteria. Instead, they mentioned relying on the expertise of special education teachers and seeking guidance from more experienced colleagues.

In both countries, the participants emphasised the role of parental cooperation in fostering a successful learning process for children from diverse cultural backgrounds. Based on their previous work experiences, they acknowledged that active communication and regular meetings with both children and parents, where feedback on children’s educational progress was discussed, were essential components of formative assessment. However, many participants criticised their respective teacher education programmes for not adequately addressing this topic and only providing them with superficial knowledge about family-school cooperation. Furthermore, the participants in Denmark expressed concerns about the lack of opportunities for family-school cooperation during their on-site training organised by the university colleges. In some cases, they were allowed to observe meetings with parents, but active participation was discouraged by the supervisory teachers. They believed that formal training in this area would be beneficial in equipping them with the necessary skills and strategies to establish meaningful partnerships with families.

Regarding summative assessment, the participants held varying opinions. In Iceland, several participants regarded summative assessment based on norm-referenced tests as necessary due to its role in identifying knowledge gaps between culturally diverse children and their Icelandic peers. They emphasised the significance of summative assessment in the Icelandic context, where admission to highly sought-after upper secondary schools is competitive and largely depends on the grades achieved at the end of compulsory schooling. In Denmark, the majority of participants expressed the view that summative assessment is irrelevant and unfair for evaluating children from diverse cultural backgrounds. This sentiment is exemplified by a quotation from Dea, a participant specialising in teaching mathematics, which resonates with the perspectives shared by other Danish participants.

I don’t think the summative assessment is fair [...] It is a bit like if I were given assignments in German. Although I can speak German well, I understand German, but if I were given assignments, I would not understand them in the same way because they would be written in academic German. And I think it would be the same for plurilingual pupils when they get questions in Danish [...] I think I would ask my superior if these pupils could be given more time because it could help them like it helps pupils with dyslexia. (Dea)

In summary, the participants in both countries needed a greater understanding of how to integrate cultural considerations into formative and summative assessment practices. Their reflections primarily revolved around assessing language development and offering parents and pupils feedback and support on enhancing their language proficiency. However, there appeared to be an absence of comprehensive awareness and well-defined strategies to address the broader cultural dimensions of assessment.

Assessment of children’s well-being

Although the participants were not specifically prompted to reflect on the assessment of the well-being of children from diverse cultural backgrounds, most of them raised this topic in both countries. They underlined that the assessment of well-being, particularly for newly arrived children, holds greater relevance in certain instances than assessing their academic knowledge in school subjects. This emphasis on well-being assessment underscores the recognition of the multifaceted needs and challenges faced by culturally diverse children, bringing to the forefront the importance of considering their holistic development beyond academic performance. An Icelandic participant, Ína, who specialises in teaching young children (grades 1 to 4), provided a concise summary of why the assessment of well-being is critically important.

Not much happens if you feel bad at school. You don’t learn much. You are just waiting to get away. And, of course, it is hard if you don’t understand anyone. What if maybe no one wants to be around you? Feeling bad at school from the age of 6 to the age of 16 – that’s quite a lot. (Ína)

The participants in both countries recognised the significance of cultivating positive learning environments and facilitating communication among pupils, such as through group work. They placed a high priority on promoting children’s sense of belonging and fostering well-being. However, they revealed that they received limited training in promoting well-being and a sense of belonging, except three participants in Iceland who specialised in inclusive special education. These participants had mandatory courses on diversity and multicultural education within their programme, providing them with a more comprehensive understanding of the topic compared to other participants.

The following discussion section further explores the implications of the findings. It puts forth recommendations to enhance teacher education programmes to provide student teachers with the theoretical knowledge and practical skills needed to work successfully in culturally diverse classrooms.

Discussion

The findings shed light on the perspectives and experiences of student teachers in Denmark and Iceland regarding the assessment practices suitable for children from diverse cultural backgrounds. Although the participants revealed having limited theoretical knowledge of such assessment practices, many of them showcased approaches, examples, and reflections that resembled, to some extent, various principles of culturally responsive assessment. Their reflections were mainly based on their field experiences, indicating a clear gap in their respective teacher education programmes.

Among the various assessment practices discussed in the interviews, the so-called ‘Swedish’ assessment stood out in Iceland as the most systematic and standardised. By involving a multidisciplinary team of experts, the ‘Swedish’ assessment framework offers a structured and consistent approach to evaluating children’s previous knowledge, aiming at a more tailored educational experience (Directorate of Education (Iceland), 2016). While the participants have acknowledged the ‘Swedish’ assessment framework for its positive aspects, it is important to point out its potential flaws. The documents published by the Directorate of Education (2016) emphasise the need for the translation of assessment tasks into children’s strongest languages. However, there is limited attention given to the consideration of cultural bias in assessment, which is, according to Nortvedt et al. (2020), recognised as a crucial dimension of culturally responsive assessment. Another notable gap in the ‘Swedish’ assessment framework is the lack of explicit guidance on quality control for translated assignments. Although ethical considerations are provided for interpreters, minimal attention is given to the training or qualifications required for interpreting the assessment interview and the tasks. As highlighted by Padilla and Borsato (2008), appropriate translation can be a complex task that demands specialised training and comprehensive knowledge of the cultures involved, the content being assessed, and the intended purposes of the assessment.

Turning to the unstructured approaches to assessment discussed by the participants in both countries, it is evident that while there was an expressed intention to develop individual assessment criteria for formative assessment, there was a lack of concrete examples demonstrating a systematic approach. These findings align with previous research conducted by Herzog-Punzenberger et al. (2020), which similarly revealed that teachers’ endeavours to adapt assessment and grading practices to support students often relied on unstructured methods rooted in their own assumptions and observations. In the current study, it was evident that both Danish and Icelandic participants possessed a genuine desire to tailor assessments to meet children’s diverse needs. However, the absence of proper training hindered their ability to do so in a consistent manner. In the context of both pre-instructional and formative assessment, the participants often relied on the expertise of special education teachers and experienced colleagues. This suggests a potential gap in their respective teacher education programmes. Although seeking support and guidance from colleagues is indeed beneficial, teacher education must equip future educators with the necessary tools and strategies to apply assessment independently. Relying on the practices of experienced colleagues may lead to a homogenisation of teaching approaches and potentially perpetuating outdated methods (Hargreaves, 2003). It is important to clarify that teacher education should not aim at providing teachers with a universal approach to assessment, as such an approach does not exist in a multicultural context (Brookhart & Nitko, 2019; Kirova & Hennig, 2013). Instead, the aim of teacher education should be to foster an understanding and awareness of pupils’ diverse cultural perspectives, experiences, and needs.

While reflecting on pre-instructional and formative assessment, the participants in both countries were primarily centred on assessing children’s language proficiency. While mastering the school language is undeniably crucial for academic success, emphasising language alone might not encompass the complexities of culturally responsive assessment (Borsato & Padilla, 2008). Utilising proficiency in the school language as the sole determinant of success overlooks the significant impact of cultural and social dimensions within the educational process (Herzog-Punzenberger et al., 2020; Padilla & Borsato, 2008). Culturally responsive assessment emphasises the need to consider the context in which assessment tasks are employed, as well as how they are intertwined with cultural practices. These factors must not only be integral to the assessment process but also taken into account during the design of assessment tasks (Borsato & Padilla, 2008; Kirova & Hennig, 2013; Padilla & Borsato, 2008). Language portraits, as described by Dressler (2014) and Busch (2012), were mentioned by several participants as a potential approach to assess children’s language repertoires. One participant in Denmark demonstrated creative thinking by going beyond the conventional approach, having proposed the idea of introducing culture portraits as an additional tool to gain a deeper understanding of her pupils’ cultural backgrounds. By encouraging children to create culture portraits, the participant recognised the potential to uncover more than just linguistic aspects. The culture portraits would visually represent the children’s cultural backgrounds, allowing for a richer exploration of their values and experiences.

Most participants put emphasis on assessing children’s well-being in schools. These findings align with a growing body of evidence that highlights the complexity of children’s well-being, particularly for those from diverse cultural backgrounds (Einarsdóttir & Rúnarsdóttir, 2022; Gunnþórsdóttir & Aradóttir, 2021). The participants in both countries acknowledged the importance of building positive and welcoming learning environments and promoting communication among pupils, with activities like group work being described as good strategies. The emphasis on well-being reflects a nuanced understanding of education that extends beyond academic achievement. It acknowledges the holistic nature of children’s development, wherein emotional, social, and cultural dimensions are intertwined with academic achievement (Borsato & Padilla, 2008; Kirova & Hennig, 2013; Padilla & Borsato, 2008). However, the emphasis on well-being also presents a challenge. Creating truly empowering environments in multicultural schools requires significant reflection, skill, and ongoing professional development (Gay, 2000; Ladson-Billings, 2021; Nieto, 2010). Teachers must be appropriately trained to recognise and respond to the subtle cues and complex dynamics that can impact children’s sense of belonging and well-being, especially when cultural diversity is considered (Einarsdóttir & Rúnarsdóttir, 2022; Gunnþórsdóttir & Aradóttir, 2021; Nieto, 2010). It calls for a more comprehensive and multifaceted approach to teacher education, one that balances content knowledge with cultural competence. Moreover, the study’s findings hint at a broader shift in educational paradigms, where well-being is not just a desirable outcome but one of the central components of the learning process.

In summary, Danish and Icelandic student teachers felt they needed more support and training to successfully implement culturally responsive assessment practices. While their teacher education programmes included the topic of multicultural education, the extent and quality of the training varied significantly across the programmes. This study raises awareness of the importance of paying special attention to cultural perspectives throughout teacher education, regardless of specialisations, as teachers across all fields must be prepared to work with and support cultural and linguistic diversity in their classrooms. A comprehensive integration of cultural perspectives into teacher education would reflect a commitment to social justice and contemporary educational imperatives.

Conclusion

Is culturally responsive assessment an illusion or a reality? Based on the analysis of interviews collected during this research project, it presently remains more of an illusion. This is evidenced by the observed lack of a holistic understanding among the student teachers regarding assessment methods that account for children’s cultural diversity. These findings underscore the crucial role and responsibility of teacher education, which, as shown in the study, has not adequately equipped the students with knowledge and skills of culturally responsive assessment. Moving from the illusion of culturally responsive assessment to a tangible reality requires a paradigm shift in teacher education. Rather than simply emphasising the inclusion of silenced minorities, teacher education must recognise cultural diversity as an essential prerequisite for learning and teaching. This means embedding cultural perspectives into the core curriculum, fostering a learning environment that actively encourages cultural awareness, and offering on-site training that requires the use of culturally responsive teaching and assessment methods. Teacher educators are responsible for empowering student teachers to challenge discriminatory discourses and their manifestations in teaching and assessment practices in educational institutions. Practical tools and methods must be provided to facilitate this empowerment, including but not limited to comprehensive guidelines that provide instructions on designing, implementing, and evaluating assessments that consider children’s diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Moreover, higher educational institutions must facilitate ongoing professional development to keep teacher educators abreast of the evolving trends and practices in multicultural education, enabling them to pass the new insights on to their students. Only through a concerted and comprehensive effort can future teachers cultivate cultural competence essential for tailoring their teaching and assessment practices to the diverse needs of children in multicultural schools.

References

Berry, J. W., & Hou, F. (2017). Acculturation, discrimination and wellbeing among second generation of immigrants in Canada. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 61, 29-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.08.003

Borsato, G. N., & Padilla, A. M. (2008). Educational assessment of English-language learners. In L. A. Suzuki & J. G. Ponterotto (Eds.), Handbook of Multicultural Assessment: Clinical, Psychological, and Educational Applications (3 ed., pp. 471-489). Jossey-Bass.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful Qualitative Research. Sage.

Bray, M., Adamson, B., & Mason, M. (2007). Different models, different emphases, different insights. In M. Bray, B. Adamson, & M. Mason (Eds.), Comparative Education Research: Approaches and Methods (pp. 363-380). Springer.

Brookhart, S. M., & Nitko, A. J. (2019). Educational Assessment of Students. Pearson.

Busch, B. (2012). The linguistic repertoire revisited. Applied Linguistics, 33(5), 503-523. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/ams056

Daníelsdóttir, H. K., & Skogland, H. (2018). Staða grunnskólanemenda með íslensku sem annað tungumál. Menntamálastofnun. https://mms.is/sites/mms.is/files/isat-nemendur-greining_feb_2018_1.pdf

Danske professionshøjskoler. (2022). Fakta om læreruddannelsen. https://danskeprofessionshojskoler.dk/fakta-om-laereruddannelsen/

Directorate of Education (Iceland). (2016). Upplýsingar fyrir skólastjóra og kennara um stöðumat og mat á þekkingu nemenda af erlendum uppruna. https://mms.is/almennar-upplysingar

Dressler, R. (2014). In the classroom. Exploring linguistic identity in young multilingual learners. TESL Canada Journal, 32(1), 42–52. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1057309.pdf

Education Act (Iceland). (2008). Lög um grunnskóla nr. 91/2008. https://www.althingi.is/lagas/153a/2008091.html

Einarsdóttir, J., & Rúnarsdóttir, E. M. (2022). Fullgildi leikskólabarna í fjölbreyttum barnahópi: Sýn og reynsla foreldra. Tímarit um uppeldi og menntun, 31(1), 43-67. https://doi.org/10.24270/tuuom.2022.31.3

Fairbrother, G. P. (2007). Quantitative and qualitative approaches to comparative education. In M. Bray, B. Adamson, & M. Mason (Eds.), Comparative Education Research. Approaches and Methods (pp. 39-62). Springer.

Frederiksen, P. S., Løkkegaard, L., & Rasmussen, A. Ø. (2022). Etniske minoritetsdrenges læring i folkeskolen. CEPRA-Striben, 30, 42–53. https://doi.org/10.17896/UCN.cepra.n30.482

Frisby, C. L. (2008). Academic achievement testing for culturally diverse groups. In L. A. Suzuki & J. G. Ponterotto (Eds.), Handbook of Multicultural Assessment: Clinical, Psychological, and Educational Applications (3 ed., pp. 520-541). Jossey-Bass.

Gay, G. (2000). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research and practice. Teachers College Press.

Grapin, S. L., Griffin, C. B., Naser, S. C., Brown, J. M., & Proctor, S. L. (2019). School-based interventions for reducing youths’ racial and ethnic prejudice. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 6(2), 154-161. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732219863820

Gunnþórsdóttir, H., & Aradóttir, L. R. (2021). Þegar enginn er á móti er erfitt að vega salt: Reynsla nemenda af erlendum uppruna af íslenskum grunnskóla. Tímarit um uppeldi og menntun, 30(1), 51-70. https://doi.org/10.24270/tuuom.2021.30.3

Gústafsdóttir, A., & Sigurðardóttir, I. Ó. (2020). „Gagnlegast að sjá þessa hluti sem maður sér ekki venjulega“: Starfendarannsókn um mat á námi og vellíðan leikskólabarna af erlendum uppruna. Netla - Veftímarit um uppeldi og menntun. https://doi.org/10.24270/serritnetla.2020.6

Hargreaves, A. (2003). Teaching in the Knowledge Society: Education in the Age of Insecurity. Teachers College Press.

Herzog-Punzenberger, B., Altrichter, H., Brown, M., Burns, D., Nortvedt, G. A., Skedsmo, G., Wiese, E., Nayir, F., Fellner, M., McNamara, G., & O’Hara, J. (2020). Teachers responding to cultural diversity: Case studies on assessment practices, challenges and experiences in secondary schools in Austria, Ireland, Norway and Turkey. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 32(3), 395-424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-020-09330-y

Kirova, A., & Hennig, K. (2013). Culturally responsive assessment practices: Examples from an intercultural multilingual early learning program for newcomer children. Power and Education, 5(2), 106-119. https://doi.org/10.2304/power.2013.5.2.106

Ladson-Billings, G. (2021). Three decades of culturally relevant, responsive, & sustaining pedagogy: What lies ahead? The Educational Forum, 85(4), 351-354. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2021.1957632

Ministry of Children and Education (Denmark). (2016). Bekendtgørelse om folkeskolens undervisning i dansk som andetsprog (BEK nr 1053 af 29/06/2016). https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2016/1053

Ministry of Education, Science and Culture (Iceland). (2014). Reference report of the Icelandic qualifications framework ISQF to the European qualifications framework for life long learning EQF. https://europa.eu/europass/system/files/2022-05/Icelandic_Referencing_Report%5B1%5D.pdf

Ministry of Higher Education and Science (Denmark). (2022). Aftale på plads om ny og bedre læreruddannelse: Flere timer, mere praktik og større økonomi. https://ufm.dk/aktuelt/pressemeddelelser/2022/aftale-pa-plads-om-ny-og-bedre-laereruddannelse-flere-timer-mere-praktik-og-storre-okonomi

Ministry of Higher Education and Science (Denmark). (2023). Bekendtgørelse om uddannelsen til professionsbachelor som lærer i folkeskolen (BEK nr 374 af 29/03/2023). https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2023/374

Ministry of Higher Education and Science (Denmark). (n.d.). Om kvalifikationsrammen. https://ufm.dk/uddannelse/anerkendelse-og-dokumentation/dokumentation/kvalifikationsrammer/om-kvalifikationsrammen

Mock-Muñoz de Luna, C., Granberg, A., Krasnik, A., & Vitus, K. (2020). Towards more equitable education: Meeting health and wellbeing needs of newly arrived migrant and refugee children—perspectives from educators in Denmark and Sweden. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 15(2), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2020.1773207

Nieto, S. (2010). The light in their eyes: Creating multicultural learning communities. Teachers College Press.

Nortvedt, G. A., Wiese, E., Brown, M., Burns, D., McNamara, G., O’Hara, J., Altrichter, H., Fellner, M., Herzog-Punzenberger, B., Nayir, F., & Taneri, P. O. (2020). Aiding culturally responsive assessment in schools in a globalising world. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 32(1), 5-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-020-09316-w

Padilla, A. M., & Borsato, G. N. (2008). Issues in culturally appropriate psychoeducational assessment. In L. A. Suzuki & J. G. Ponterotto (Eds.), Handbook of Multicultural Assessment: Clinical, Psychological, and Educational Applications (3 ed., pp. 5-21). Jossey-Bass.

Teacher Education Act (Iceland). (2019). Lög um menntun, hæfni og ráðningu kennara og skólastjórnenda við leikskóla, grunnskóla og framhaldsskóla nr. 95/2019. https://www.althingi.is/lagas/153b/2019095.html

Vervaet, R., Van Houtte, M., & Stevens, P. A. J. (2018). Multicultural teaching in Flemish secondary schools: The role of ethnic school composition, track, and teachers’ ethnic prejudice. Education and Urban Society, 50(3), 274-299. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124517704290