Vol 8, No 1 (2024)

https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.5514

Article

A Cross-cultural Comparison of ELT Curricula of Senior Secondary Schools in Mainland China and Hong Kong: A Governmentality Perspective

Xiaoli Su

Sichuan International Studies University/Chinese University of Hong Kong

Email: xiaolisu@link.cuhk.edu.hk

Dorottya Ruisz

Oskar-von-Miller-Gymnasium München

Email: ruisz@gmx.de

Xiao Zhang

Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München

Email: zhangxiao201310@gmail.com

Abstract

English holds significant importance as a foreign language in Mainland China and Hong Kong, where ongoing curriculum revisions are shaped by economic and sociocultural advancements. Previous research on English Language Teaching (ELT) curriculum comparisons in Asia has frequently overlooked the exploration of underlying sociocultural and socio-political factors that contribute to the observed similarities and differences. Adopting a governmentality perspective informed by Dean's analytics of government theory, this cross-cultural comparative study investigates the ELT curricula in senior secondary schools in Mainland China and Hong Kong. Through this analysis, the study explores how sociocultural and socio-political factors interact to influence the educational landscapes. By examining the dimensions of problematizations, rationalities, techne, and teleology within the curricula, the research uncovers common challenges, rationales, approaches, and objectives, as well as distinctions arising from the unique sociocultural, political, and economic contexts of Mainland China and Hong Kong. This examination underscores the profound impact of these contextual factors on ELT curriculum design, contributing valuable insights to the cross-cultural discourse. Furthermore, the findings lay the groundwork for future research and policy development in the realm of ELT curricula, emphasizing the need for additional studies employing diverse methods and focusing on the implemented and experienced curriculum in senior secondary schools to provide a comprehensive understanding of English language education in both Mainland China and Hong Kong.

Keywords: ELT curriculum, Mainland China, Hong Kong, sociocultural theory, governmentality

Introduction

English language curricula in various settings have consistently been shaped by the prevailing sociocultural agenda. Recent years have witnessed significant transformations in the English language curriculum reforms of Hong Kong and Mainland China (Li, 2018; Liu, 2016). Historically and culturally, both Hong Kong and Mainland China bear the influence of Confucianism and Daoism, and they employ a similar written Chinese language. Confucianism emphasizes moral self-cultivation and a predefined socio-political order. Daoism promotes balance with nature and harmony. In the intrapersonal domain, Chinese culture fosters modesty, collectivism, and structured learning from authority figures. In the interpersonal domain, it values relationship maintenance and social harmony (Chan & Leung, 2014). However, due to its unique history, Hong Kong developed as a dynamic fusion of traditional Chinese culture, Western influences, and capitalist values (Kan, 2010). This unique blend, enriched especially by Confucian moral principles, has left a lasting impact on the region's identity and sociocultural dynamics. Following the handover of Hong Kong to the People's Republic of China in 1997, it has functioned as the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR), with notable differences persisting in political, economic, legal, and educational systems. These disparities extend to language policies as well. According to Article 9 in the Basic Law of 1997,[1] English continues to hold official language status in Hong Kong alongside Chinese. Consequently, students in Hong Kong encounter a unique language environment. The Education Bureau of Hong Kong has set the objective of developing biliterate (proficient in written Chinese and English) and trilingual (fluent in Cantonese, Mandarin, and English) students (Li & Leung, 2020). Contrastingly, the significance of English in Mainland China during this post-colonial era is no less pronounced than in Hong Kong. Since 2001, English has been integrated as one of the three core subjects at all school levels starting from Grade 3 (Pan, 2015). This growing interest in English education reflects China's expanding need to engage with the world and compete on a global scale economically, socially, culturally, academically, and politically (Khan et al., 2019). Regardless of their chosen majors, the English language is a requisite for all individuals taking college entrance examinations in Mainland China, similar to the situation in Hong Kong (Tong, 2021). Despite the cooling down of “English fever” in societies at large in recent years, English still maintains its status as a global language and international lingua franca, occupying a prominent position as the most crucial foreign language in Mainland China (Fan, 2023).

Despite the shared emphasis on the importance of English, there exist distinctions in English language teaching between Hong Kong and Mainland China. This paper focuses specifically on the ELT curricula for senior secondary schools. The decision to concentrate on senior secondary schools, as opposed to primary or junior secondary schools, is rooted in several key considerations. Specifically, senior secondary schools offer an ideal vantage point for comprehending the depth and complexity of English language curricula from the sociocultural perspective. They typically feature more content-focused and advanced English programs, providing a context in which students' language abilities are further honed. These schools serve students aged 15 to 19, a pivotal stage for language development and a crucial period for assessing language proficiency. Additionally, this focus is pertinent because senior secondary education often represents a transitional phase preceding higher education, where English proficiency is paramount, particularly in international academic contexts. It's a key phase for preparing students not only for the most important college entrance exam but also for their future careers.

While numerous studies have conducted comparisons of English curricula, they often stop short of delving into the deeper socio-political and sociocultural factors that influence the design and content of these curricula. This study aims to address this gap by specifically focusing on the English curricula for senior secondary schools in Hong Kong and Mainland China. It examines the curriculum documents issued by the Curriculum Development Council (CDC) in 2015 for Hong Kong and the Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China (MOE) in 2017. By concentrating on the intended curriculum, we seek to gain insights into the educational objectives and strategies underpinning these curricula, thereby shedding light on the broader social, political, and cultural factors at play within the educational systems of these two regions (Nichols & Cormack, 2001). Incorporating the political dimension into our sociocultural perspective is essential, as it enables us to discern how government policies, national ideologies, and geopolitical considerations intersect with the design of English curricula. However, it's crucial to clarify that our primary emphasis is on the intended curriculum, and we do not delve into the exploration of the implemented and experienced curriculum, which falls beyond the scope of this paper (Schubert, 1986).

In the subsequent sections, the existing literature will be reviewed, and the conceptual framework, research questions, and methodology will be presented. The findings will then be reported, highlighting the similarities and differences and the underlying sociocultural and socio-political factors.

Literature review

Status of English in Hong Kong and Mainland China

English holds significant importance in both Hong Kong and Mainland China, contributing to personal, economic, social, and cultural development. It is a compulsory core subject from primary school to tertiary level and plays a substantial role in high-stakes examinations. In Mainland China, English has been established as one of the three core subjects, alongside Chinese and Mathematics, since the resumption of the National College Matriculation Examination in 1978 (Tong, 2021). Similarly, in Hong Kong, English language tests are mandatory alongside three other core subjects (Chinese Language, Mathematics, and Citizenship and Social Development, formerly Liberal Studies) in the Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education Examination (HKDSE) since 2012 (Tsang & Isaacs, 2021). English also plays a pivotal role in driving economic and social development in both regions. Influenced by Confucianism, Hong Kong and Mainland China prioritize aligning schools with societal needs, cultivating good citizenship, and acquiring economically productive skills (Hu & Adamson, 2012). This Confucian perspective influences the alignment of schooling and societal needs in ways that prioritize collective welfare, social order, and hierarchical relationships within the community. Proficiency in English is considered an indispensable skill for students to contribute to economic and social development, aligning with the global trend towards globalization.

In the context of Hong Kong, English was initially introduced as a colonial language and gradually gained significance due to its close association with economic development (Adamson & Lai, 1997). Before the handover of sovereignty in 1997, over 90% of secondary schools in Hong Kong adopted English as the medium of instruction (EMI) (Li, 1999). Subsequently, the mother-tongue education policy issued by the HKSAR required a transition to Chinese-medium instruction (CMI) in over 70% of secondary schools (Li, 1999). However, the competition for English-medium instruction (EMI) schools remained fierce due to the enthusiasm of students and parents towards English education. The inclusion of the Chinese language in the official language system did not alter the pro-English linguistic hierarchy, as English continued to be perceived as economically more beneficial than Chinese (Fung, 2021). Consequently, the implementation of the medium of instruction (MOI) policy fine-tuning in 2010 provided schools with greater flexibility in choosing between CMI or EMI for various subjects throughout the curriculum (Hu & Gao, 2018).

In Mainland China, English education policies have evolved over the past three decades (Gao, 2018). Initially, English had a lower status compared to Russian due to the Soviet influence (Adamson, 2004). The 1960s marked a shift toward more curriculum diversity, while the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) made English vulnerable in the education system. However, it regained significance with the Reform and Opening-up Policy in the late 1970s, notably after being included in the national college entrance examination (Gaokao) in 1977. The importance of English in Mainland China grew with the 1978 opening-up policy, strengthened by its entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001, and events like the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games (Adamson, 2004; Tong, 2021; Zhao, 2016). Debates over English education policy reforms from 2013 to 2014 tempered enthusiasm for learning English, partly due to concerns about its impact on Chinese cultural identity and proficiency in the Chinese language (Gao, 2018). More recently, China has aimed to enhance its global influence by increasing the demand for high-quality foreign language professionals (Yong, 2019). However, concerns have arisen due to two new 2021 policies—the 'double reduction' and Gaokao regulation—which significantly impacted English learning (Fan, 2023; Wang, 2022). This has led to ongoing debates about the influence of "English fever" on Chinese identity and culture, with some advocating for a stronger emphasis on the Chinese language. The status of English remains a subject of debate in China, yet it retains its position as the most vital foreign language subject in pre-tertiary education, viewed as the optimal medium for the Chinese government to convey the story and voice of China to other countries (National Foreign Studies Universities Collaboration Committee for Student Affairs, 2021).

English curriculum development for Senior Secondary Education in Mainland China and Hong Kong

The development of senior secondary school English curriculum in Mainland China can be traced through five phases since the adoption of the opening-up policy in 1978, as discussed by Wang and Chen (2012). The initial phase (1978-1986) implemented the 1978 English syllabus, followed by the introduction of the 1986 syllabus in the second phase (1986-1993) to enhance teaching quality. The third phase (1993-2000) focused on communication as a teaching objective. In the fourth phase (2003), coinciding with the senior high school curriculum reform, the English curriculum underwent significant changes in aims, objectives, structure, content, teaching approach, and assessment. The fifth phase began with the issuance of the 2017 English curriculum standards for senior high schools by the Ministry of Education, representing a significant transformation of curriculum aims and structure (Wang, 2018).

Numerous studies analyse the historical evolution of the English curriculum in Mainland China and its influence on the school curriculum. They examine shifting ideologies and the changing international political and economic climate (Adamson & Morris, 1997; Cheng, 2011; Wang, 2007; Wang & Lam, 2009). Some studies compare the latest reforms with previous versions, highlighting the recognition of the humanistic value of English in fostering cognitive and personal growth (Wang & Lam, 2009). Curriculum development in Mainland China follows a top-down model, with the Ministry of Education providing guidelines and involving national surveys during the development stage (Wang & Chen, 2012).

In Hong Kong, three secondary English curricula have been issued over the past four decades. The 1975 and 1983 curricula reflect a social reconstructionist agenda, while the 1999 syllabus emphasizes progressivist values (Tong & Adamson, 2013). In 2000, an educational reform proposal called "Learning for Life, Learning Through Life" aimed to shift the focus to experiential learning, whole-person development, and integrated learning (Education Commission, 2000). The CDC presented the aims of the school curriculum in 2000, including fostering active and confident engagement in discussions in English and Chinese (including Mandarin). Since 2001, Hong Kong has been continuously developing its school curriculum, consisting of Knowledge in Key Learning Areas, Generic Skills, and Values and Attitudes. English Language Education is one of the eight Key Learning Areas. The English Language Education Key Learning Area Curriculum Guide was issued in 2002 for primary to secondary three and extended to secondary four to six in 2007, with updates in November 2015. In 2017, the English Language Education Key Learning Area Curriculum Guide (Primary 1 to Secondary 6) superseded the 2002 version following the CDC's final recommendation in December 2016 (CDC, 2017).

Studies on the Hong Kong English language curriculum primarily focus on analysing curriculum reform and changes, particularly since 1997. Carless and Harfitt (2013) examine the innovation and modification of the senior secondary school curriculum from technological, political, and cultural perspectives. Benson and Patkin (2014) discuss the role of the module "Learning English through Popular Culture" in senior secondary English language teaching. Koh (2015) criticizes the teaching of popular culture texts and suggests curriculum innovation. Hu and Gao (2018) discuss changes in involving teachers in pedagogy development, using the first language as a means of multilingual multimodal mediation, and promoting Language Across the Curriculum (LAC) in content subjects and English teaching.

Comparative studies on English curricula in Asia

Numerous studies have conducted comparisons of English curricula in different countries and regions in Asia, but they often fail to delve into the underlying sociocultural and socio-political reasons for these similarities and differences. Kim and Jeon (2005) compare the English curricula implemented in Korea, China, and Japan at the end of the last century, focusing on goals, learning levels, methods of describing objectives, and content of language skills teaching, and providing suggestions. Yang et al. (2013) compare the English curricula for senior secondary schools in Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, suggesting that Mainland China's curriculum should combine personal growth with societal development and become more "human-centred." Zhang (2016) focuses on the English curricula for primary and junior high schools in Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Singapore, emphasizing the need for greater flexibility for teachers in Mainland China to adjust teaching objectives and content.

However, few studies have explored the underlying reasons behind the similarities and differences between these curricula, and there is currently no framework that connects these differences to social and cultural factors. For example, Yang (2012) reveals that senior secondary school English curricula in Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan share common values but differ in their pursuit of those values. While she highlights potential reasons such as shared cultural psychology, common societal progress requirements, and historical, cultural, and economic factors, there is a lack of in-depth curriculum analysis employing a comprehensive framework.

Since Hong Kong's return to China in 1997, both Hong Kong and Mainland China have experienced exponential changes in political, economic, social, and cultural aspects. Both regions have embarked on a new wave of curriculum reform in English education, as mentioned in the literature review. However, the relationship between these changing sociocultural factors and the reforms in English curricula remains unclear. Therefore, it is crucial to address this issue by comparing the updated English curricula using Dean’s analytics of government theory as the conceptual framework.

Conceptual framework

In this study, we employ a conceptual framework that integrates Dean's analytics of government theory (Dean, 2010) to provide a comprehensive understanding of the ELT curricula in senior secondary schools in Mainland China and Hong Kong. This framework enables us to analyse the power dynamics, governance, and rationalities that shape these curricula and influence curriculum design and objectives.

First, Dean's analytics of government theory is deeply rooted in the work of Michel Foucault and offers a systematic approach to deconstruct and understand the underlying mechanisms and intentions behind governance practices (Dean, 2010). This framework consists of four key components (Dean, 2010; Hamilton et al., 2019): (1) Problematizations: These involve identifying the issues and concerns that authorities perceive as requiring intervention or attention. In our curriculum analysis, problematizations will help us recognize the educational challenges and goals policymakers and stakeholders believe necessitate a curriculum response and update. This includes concerns related to language proficiency, cultural identity, international competitiveness, and educational aims. (2) Rationalities: Rationalities encompass the underlying logic, reasoning, and ideologies that inform how authorities address identified problems. In the context of curriculum development, analysing rationalities entails exploring the values, beliefs, and educational philosophies that shape the curriculum's goals, content, and methods. This aspect helps uncover the "why" behind curriculum choices. (3) Techne: Techne pertains to the techniques, practices, methods, and tools employed to address identified problems based on the rationalities in place. In curriculum analysis, techne relates to the instructional methods, assessment strategies, teacher training, and pedagogical tools used to implement the curriculum. It focuses on the practical means by which governance is enacted and addresses the "how" of curriculum delivery. (4) Teleology (Telos): Teleology explores the ultimate goals or purposes of governance and examines the desired outcomes or transformations that authorities aim to achieve through their governance practices. In the context of curriculum analysis, teleology involves examining what education authorities aim to accomplish with a specific curriculum, including goals related to student achievement, cultural preservation, international communication, or societal change. By applying Dean's analytics of government theory, we aim to uncover the governance mechanisms that shape the ELT curricula in Mainland China and Hong Kong. This theoretical lens will help us understand how power, knowledge, and governance intersect in the realm of curriculum development, providing insights into the socio-cultural dimensions and implications of educational policies and practices.

By using Dean's (2010) analytics of government theory, this study examines the similarities and differences in ELT curricula between Hong Kong and Mainland China. It is important to emphasize that the authors of this study share the perspective that knowledge is influenced by the broader cultural, political, and historical context. Therefore, our epistemological standpoint is in harmony with the fundamental principles of social constructivism, which underscore the importance of 'social contexts, interaction, the exchange of viewpoints, and interpretive understandings' (Charmaz, 2014, p. 14).

In light of this, the current study aims to explore the following research questions:

1. From a governmentality perspective, what are the similarities and differences in the ELT curricula of senior secondary schools in Mainland China and Hong Kong?

2. What sociocultural and socio-political factors explain the similarities and differences?

Method

The present study employs a qualitative content analysis approach (Flick et al., 2004), specifically utilizing thematic analysis to examine the two target documents (see Table 1). The bottom-up thematic analysis enables us to consider the top-down governmentality perspectives to provide a holistic view of curriculum development and its implications. Thematic analysis involves a process of pattern recognition within the data of the documents (Bowen, 2009). The researcher conducts careful reading and rereading of the data, performing coding and constructing categories to identify and explore the themes present. To facilitate the organization and summary of codes and categories, Microsoft Excel was utilized as a tool in the analysis process. This approach allows for a systematic exploration of the data, enabling the identification of key themes and patterns within the English curricula of senior secondary schools in Mainland China and Hong Kong.

Table 1. Data for Analysis

|

Regions |

Data |

Year |

Compiling Language |

|

Mainland China |

English Curriculum Standards of Senior Secondary School (MOE) |

2017 |

Chinese |

|

Hong Kong |

English Language Curriculum and Assessment Guide (Secondary 4-6/ Age 15-19) (CDC) |

2007 [with updates in November 2015] |

English |

As the primary instrument of data selection and analysis, the researcher's skills, intuition, and interpretive lens play a crucial role in the process (Bowen, 2009). To enhance the interpretation of the data, the study draws upon Dean's (2010) analytics of government theory, adding a top-down dimension to the bottom-up thematic analysis. This approach makes the analysis more interactive and allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the data (see the Appendix). In combining the thematic analysis with the theoretical framework, the study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the English curricula of senior secondary schools in Mainland China and Hong Kong, considering both the data-driven themes and the broader context of curriculum development.

Findings

Using Dean's analytics of government theory, we analyse the differences and similarities between Hong Kong and Mainland China's curricula from four aspects: problematizations, rationalities, techne, and teleology.

Problematizations

In the context of analysing the ELT curricula in both Hong Kong and Mainland China, problematizations encompass specific issues and concerns recognized by educational authorities, policymakers, and stakeholders, highlighting areas in need of attention and improvement. These problematizations serve as common challenges that both regions face when designing their English curricula for senior secondary education.

One shared challenge revolves around preparing students for global interaction and enhancing competitiveness on the international stage. In a rapidly globalizing world, English is universally acknowledged as the language of global communication, essential for accessing knowledge worldwide, facilitating international business and trade, and fostering intercultural competence (CDC, 2015; MOE, 2017). Both Hong Kong and Mainland China prioritize English proficiency to ensure their students are well-equipped for effective global interaction. Additionally, a second common concern is empowering learners with the skills and capabilities needed to thrive in a dynamic global environment. Both curricula underscore English proficiency as a cornerstone for social and economic progress, aligning educational objectives with the evolving demands of society (CDC, 2015; MOE, 2017). Moreover, overarching educational challenges remain unified. Both regions aspire to equip their students with critical thinking, problem-solving skills, creativity, and adaptability, recognizing the pivotal role of these competencies in navigating the evolving demands of the modern world (CDC, 2015; MOE, 2017). While Hong Kong and Mainland China address their respective problematizations within the framework of their unique educational contexts, they share a common commitment to advancing their educational systems and preparing students for holistic development.

Within the context of shared problematizations, notable differences arise, primarily influenced by the unique sociocultural, political, and economic contexts of Hong Kong and Mainland China. Hong Kong's educational priorities are intrinsically linked to its status as a global financial hub and international trade center. Consequently, its curriculum places a strong emphasis on maintaining and enhancing English proficiency for professional communication, addressing the practical needs of the local workforce. The CDC underscores its need to "maintain and enhance students' proficiency in the Chinese language and English language, and to nurture students' biliteracy and trilingualism" (CDC, 2015, p. 3). In contrast, Mainland China's curriculum reflects a broader commitment to cultural and political identity within a global context. While the primary focus remains on the English language, it has also expanded its offerings to include other foreign languages, such as German, French, and Spanish. This expansion is part of an effort to "develop a sense of community with a shared future for mankind and multicultural awareness," as articulated in the Mainland China curriculum. The MOE document additionally emphasizes the importance of students "deepening their understanding of the motherland culture, enhancing patriotism, and fostering cultural confidence" to "adapt to the global multipolarization, economic globalization, and social informatization" (MOE, 2017, p. 2).

These regional distinctions extend to the need to improve cross-cultural understanding. In Hong Kong, the primary challenge revolves around fostering intercultural awareness "through interaction with a wide range of texts and people from diverse cultural backgrounds, an appreciation of the relationship of Hong Kong to other countries and cultures, and an understanding of the interdependent nature of the modern world" (CDC, 2015, p. 147). Notably, the Hong Kong curriculum does not emphasize the need to strengthen national identity and patriotism, which is a priority in Mainland China. As the MOE document clearly states in the Foreword, the curriculum was “designed to reflect Xi Jinping's Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” by organically integrating “core socialist values, fine traditional Chinese culture, revolutionary culture, and advanced socialist culture” (MOE, 2017, p. 4). Mainland China's focus is on deepening students' understanding of the multifaceted Chinese culture and its role in global mutual understanding, with the MOE placing significant emphasis on nurturing cultural confidence and instilling socialist values, patriotism, and party loyalty.

Rationalities

In comparing Hong Kong and Mainland China's curricula, understanding their rationalities is crucial. It reveals commonalities and differences in core beliefs and the underlying philosophical and ideological foundations that inform the "why" behind curriculum choices.

Within the context of curriculum development, both Mainland China and Hong Kong exhibit similarities in the underlying philosophies and beliefs that drive their educational choices. Foremost among these commonalities is the emphasis on fostering global competence and the pivotal role of the English language in enabling it. Educational authorities in both regions share the conviction that English serves as the gateway to global communication and understanding. In the Hong Kong document, “proficiency in English is essential for helping Hong Kong maintain its current status and further strengthen its competitiveness as a leading finance, banking and business centre in the world” (CDC, 2015, p. 2). Similarly, English is regarded as “an indispensable communication tool for international exchanges and cooperation, and an important instrument for recording thoughts and cultures” in the Mainland China curriculum (MOE, 2017, p. 1). This shared philosophy underpins the rationale for placing English proficiency at the core of their curricula, with the overarching goal of equipping students with the language skills necessary for effective international engagement. These rationalities converge in their commitment to preparing students to excel in an increasingly globalized world. Another significant commonality is the commitment to empowering learners. Curriculum choices in both Mainland China and Hong Kong reflect the belief that education should extend beyond the mere transmission of subject-specific knowledge. Rather, it should focus on nurturing well-rounded individuals equipped with essential skills such as critical thinking, problem-solving, creativity, and adaptability (CDC, 2015; MOE, 2017). These rationalities are rooted in the understanding that education should not merely convey factual knowledge but should also foster the development of individuals’ essential twenty-first century skills capable of addressing the multifaceted challenges of the modern era (Liu et al., 2017). The emphasis on curriculum integration, evident in both regions through the promotion of cross-curricular links (CDC, 2015; MOE, 2017), further underscores their shared philosophy. This philosophy advocates a multidisciplinary approach to learning, wherein knowledge is interconnected and comprehensive. These rationalities inform curriculum choices that prioritize a deep and meaningful understanding of subjects and competencies.

While there are notable similarities in the rationalities guiding curriculum development in Mainland China and Hong Kong, there are also distinctive differences. One significant contrast lies in their orientation toward cultural identity and global citizenship. In Mainland China, the underlying philosophy is deeply rooted in the broader ideological and political context, aligning with the goals and educational plans of the Communist Party (MOE, 2017). Mainland China's curriculum places a strong emphasis on preserving Chinese culture, nurturing socialist values, and fostering moral education and character development, as stated in the preface of the curriculum that the revision was “guided by Marxism-Leninism, Mao Zedong Thought, Deng Xiaoping Theory, the Theory of Three Represents, the Scientific Outlook on Development, and Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era.” (MOE, 2017, p. ii). It is also committed to the integration of modern information technologies into teaching and learning (MOE, 2017). Conversely, Hong Kong's curriculum follows a more pragmatic approach. It prioritizes “educational attainment, career advancement, personal fulfilment” (CDC, 2015, p. 2). Importantly, it does not contain explicit references to Chinese culture or political factors. The curriculum leans toward the utilitarian purpose of English for learners, focusing on preparing students for international competitiveness and academic achievement without delving into political ideology or national identity.

These significant differences in rationalities are indicative of the distinct sociocultural, political, and historical contexts of Mainland China and Hong Kong. While both regions share common educational objectives, their underlying philosophies and ideologies drive distinct curriculum choices. The contrast between the preservation of cultural identity and socialist values in Mainland China and the pragmatic focus on language proficiency in Hong Kong exemplifies how these rationalities significantly shape curriculum development.

Techne

Techne deals with the practical means for addressing identified problems, focusing on "how" curriculum design occurs. It involves the practical methods, techniques, tools, and practices applied in response to identified issues, guided by the rationalities at play. In comparing Hong Kong and Mainland China's curricula, it refers to understanding their respective techne that provide insight into how they put their educational ideologies into practice. The techne helps identify both shared and distinct dimensions including the structure of the curricula, recommended teaching content, instructional approaches, assessment methods, and the role of school-based curricular. This, in turn, sheds light on the practical aspects of their curriculum delivery methods.

Understanding the structure of the curricula is fundamental to comprehending how each region organizes its educational plans (see Figure 1). In Hong Kong, the curriculum is divided into two primary parts: Compulsory and Elective (CDC, 2015). To participate in assessments, students are required to complete both sections. The Compulsory part spans three years of senior secondary education, while the Elective part allows flexibility, enabling teachers and students to choose at least two modules from eight available options. In contrast, Mainland China's curriculum structure is notably distinct. It includes an additional component known as "Optional Compulsory."(MOE, 2017, p. 9) Here, students only need to complete the Compulsory part to meet graduation requirements. However, they have the option to take additional courses, particularly for college entrance exams. The Compulsory part in Mainland China is comparatively shorter, lasting for three-fourths of the first year (MOE, 2017). Moreover, the Elective part in Mainland China offers even greater diversity by categorizing courses into five different types, which include Advanced, Basic, Practical, Continuation, and Second Foreign Language (MOE, 2017). This diverse categorization caters to students with varying interests and needs. These structural differences in curriculum design reflect distinct approaches to both compulsory and elective components, along with the autonomy and flexibility granted to schools, teachers, and students. Additionally, the variability within Mainland China's curriculum structure can be attributed to regional disparities, where different regions may have varying requirements and needs, especially the development gaps between urban and rural areas and “imbalanced English education resources” that lead to greatly various students’ English level. (MOE, 2017, pp. 7, 11). In contrast, Hong Kong, being a more homogeneous region, does not face the same need for such extensive diversification in its curriculum structure.

Figure 1. Structure of Senior Secondary School English Curriculum of Hong Kong

and Mainland China

Curriculum content is a pivotal element in the Techne of curriculum development. To facilitate a comprehensive comparison of the Mainland China and Hong Kong ELT curricula, we have categorized the specific content recommendations into two primary areas: Themes and Modules, Knowledge and Skills.

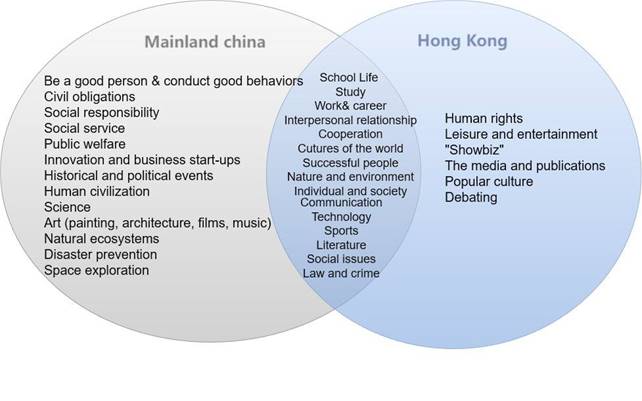

In the Mainland China curriculum, the recommended themes and modules are structured within three overarching thematic contexts: "Human and Self," "Human and Society," and "Human and Nature." These thematic contexts form the basis for ten theme groups and 32 specific themes, spanning both the elective and compulsory segments of the curriculum (MOE, 2017). These thematic contexts bear a resemblance to ancient Chinese philosophy, particularly the concept of "Tian Ren He Yi天人合一" (Heaven-and-Human Oneness) attributed to Zhuangzi, an ancient Chinese Taoism philosopher. This philosophy underscores the interconnectedness of self, society, and nature (Wang, 2007). In contrast, the Hong Kong curriculum adopts a slightly different approach by providing different content recommendations for the mandatory and elective components. The mandatory part includes suggestions for 9 modules and 19 units, while the elective part comprises 8 modules without subcategories of units. These modules are further divided into two overarching categories: "Language Arts" and "Non-Language Arts" (CDC, 2015). Figure 2 illustrates that both curricula share commonly recommended modules such as "school life," "study," "work and career," "world cultures," "social issues," "technology," "sports," and "environmental protection." However, the Mainland China curriculum distinguishes itself by encompassing a broader spectrum of modules, covering subjects like "science," "space exploration," "innovation and business start-ups," "history," and "politics." The inclusion of science and technology-related modules in the Mainland China curriculum aligns with China's "Revitalizing the Nation through Science and Education" initiative, first introduced in the "Decision on Accelerating Scientific and Technological Progress" issued by the Central Committee and the State Council of the Chinese Communist Party in 1995 (Liu et al., 2021). Furthermore, it reflects China's tradition of emphasizing history and politics due to its extensive cultural heritage and political traditions (Lu & Yan, 2022). Additionally, the Mainland China curriculum underscores "civil obligations" and "social responsibility," indicating a strong emphasis on nurturing a national identity (MOE, 2017). The emphasis on personal social responsibility may be shaped by the emphasis on collective responsibility over individual pursuits, with government initiatives playing a crucial role (Bandura, 2002). This more introspective approach portrays English learners as extensions of the nation with corresponding duties. In contrast, the Hong Kong curriculum leans toward a more Western perspective concerning themes like "human rights," "media," "publications," "popular culture," "entertainment," and "leisure activities”, which reflects a more cosmopolitan and globally connected outlook, stressing more on “personal rights, civic rights”, “personal fulfilment”, and seeking pleasure in the English medium (CDC, 2015, pp. 2, 29-30).

In terms of knowledge, Mainland China and Hong Kong emphasize the significance of meaningful contexts for learning and using English in purposeful communication in terms of linguistic knowledge. Both curricula provide detailed lists and explanations of grammatical items, vocabulary building, and learning strategies (CDC, 2015; MOE, 2017). They also recommend a variety of multi-modal text types for students to engage with. An important distinction between the two curricula lies in the emphasis on cultural knowledge. Although both curricula address the importance of an open-minded and tolerant attitude toward different cultures, a serious and positive attitude toward language learning, and a critical attitude toward ideas and values, the Mainland China curriculum provides a detailed account of the cultural knowledge that students should acquire. In addition to appreciating a variety of cultures and broadening their international perspective, the curriculum encourages students to compare different cultures with their own, with a particular focus on developing a stronger identification with traditional Chinese culture, revolutionary culture, and socialist culture to enhance their confidence in Chinese culture (MOE, 2017). Furthermore, the curriculum promotes the introduction of traditional Chinese holidays and the ability to spread Chinese culture (MOE, 2017). It also advocates for the common development of all people across the world and the idea of a shared community of destiny for humankind (MOE, 2017). In contrast, the English curriculum of Hong Kong does not include specific knowledge of Chinese culture or a comparative view between Chinese culture and other cultures.

Both curricula emphasize the core language learning skills and the integration of them in English learning: listening, reading, speaking, and writing. However, they differ in their presentation. While the Hong Kong curriculum encourages integrated skills, it presents the four skills separately (CDC, 2015). In contrast, the Mainland China curriculum integrates the five language skills into two categories in presenting content requirements: receptive and productive (MOE, 2017). The use of these two classical terms from second language acquisition theory outside of China (e.g., Krashen, 1982) echoed the claim that the revised curriculum was intended to “both suit China’s actual situation and have an international perspective” (MOE, 2017, p. i). Mainland China's curriculum, in response to the new media age, introduces "viewing" as an additional skill (CDC, 2015, p. 77). This skill requires students to understand “meaning by making use of graphics, tables, animations, symbols, and videos in multimodal texts” (MOE, 2017, p. 35). The inclusion of "viewing" aligns with the global emphasis on multimodal literacy in English language education (21st-century literacies, NCTE)[2]. Teachers are advised to emphasize the integrated use of these skills, combining activities like discussions, analyzing visual materials, and taking notes during listening exercises. This integrative approach, coupled with the inclusion of multimodal literacy in the Mainland China curriculum, supports its claim to draw on the “outstanding achievements of international curriculum reforms" (MOE, 2017, p. 2).

Figure 2. Themes and Modules of Senior Secondary School English Curriculum of Mainland China and Hong Kong

In the realm of instructional approaches, the curriculum in Mainland China introduces an activity-based learning approach as a foundational method for English language education. Teachers are encouraged to craft activities across three distinct levels: those fostering understanding and comprehension, those promoting application and practice, and those spanning transversal and innovative realms (MOE, 2017). On the contrary, the Hong Kong curriculum, while recognizing the availability of diverse teaching and learning methods to cater to varying needs and capacities, explicitly endorses task-based learning and teaching, especially for the mandatory component (CDC, 2015). While there are similarities between activity-based and task-based approaches, the main difference between activity-based and task-based language teaching lies in the broader scope of integrated, theme-based activities encompassing cultural and cognitive development in the activity-based approach (MOE, 2017), whereas task-based language teaching primarily focuses on language tasks and communication. It is noteworthy that the term "task-based" is more widely accepted within the international language teaching community (Ellis et al., 2019), whereas the Mainland China curriculum emphasizes the use of innovative instructional approaches, at least semantically, to mirror one of the underlying rationales of the curriculum design, which is to "construct a senior high school curriculum system with Chinese characteristics" (MOE, 2017, p. vi).

In terms of assessment approaches, both curricula emphasize the significance of formative assessment as the primary approach, with summative assessment playing a supplementary role throughout the three years of senior secondary studies (CDC, 2017; MOE, 2017). Formative assessment, also referred to as assessment for learning in the Hong Kong curriculum (CDC, 2017), is considered an integral part of daily teaching and learning practices. Both curricula promote self and peer assessment, the use of portfolios to track student progress over time, and the adoption of diverse assessment modes tailored to students' varying abilities, proficiency levels, and cognitive and psychological conditions (CDC, 2015; MOE, 2017). Timely and encouraging feedback is emphasized. The assessment objectives in both curricula are closely aligned with the broader learning outcomes and objectives. However, Mainland China's curriculum places more emphasis on the integrative performance and development of students in the four core competencies (MOE, 2017), which appears to be broader than the focus on the four language learning skills in the Hong Kong curriculum.

Both curricula suggest public assessment strategies at the end of senior secondary studies. Although there are some similarities in terms of alignment with the curriculum, fairness, objectivity, and reliability, there are also differences in their composition. Within the context of the Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education (HKDSE), both the public examination and moderated School-based Assessment (SBA) are administered (CDC, 2015). The specific components, weightings, and durations are suggested. The public examination (75%) spans nearly six hours, while the SBA (15%) is designed for school candidates and consists of Part A (7.5%) and Part B (7.5%), which assesses students' oral performance (CDC, 2015). In contrast, Mainland China does not include school-based assessment but relies on two examinations: The Examination of Academic Levels to check if students have met graduation requirements, and the College Entrance Examination for selecting students for further studies (MOE, 2017). Furthermore, Mainland China does not strictly regulate the components and weightings of the examinations.

The contrast in the role of school-based curricula between Mainland China and Hong Kong reflects different approaches to curriculum flexibility and customization, in line with the practical aspects associated with the Techne dimension. Mainland China encourages schools to develop school-based curricula within the elective section of the central curriculum, allowing schools to tailor the curriculum to their students' specific needs (MOE, 2017). This approach encompasses curriculum customization and teacher training, addressing specific educational demands. Conversely, Hong Kong's curriculum provides teachers with more autonomy, as “schools are strongly encouraged to capitalise on this central framework to develop their own school-based curriculum, taking into consideration factors such as learners’ needs, interests and abilities, teachers’ readiness, and the school context.” (CDC, 2015, p. 52). Collaboration with teachers from other Key Learning Areas enriches students' exposure to diverse content, study skills, and grammatical structures (CDC, 2015). These practical strategies emphasize the importance of personalized curricula to meet individual learner needs and contexts. A notable feature of the Hong Kong curriculum is its emphasis on learner-centered instruction within task-based learning and teaching, giving students more power to negotiate learning objectives, materials, and activities with teachers, as students “are relatively more mature at the senior secondary level, they should be encouraged to take an even greater degree of responsibility in choosing what and how to learn” (CDC, 2015, p. 68). In Mainland China's curriculum, although negotiation between students and teachers regarding activity requirements and assessment criteria is possible, teachers play a more prominent role in setting learning objectives (MOE, 2017). Moreover, teachers are expected to deeply analyze texts for meaning, structure, language features, and viewpoints, a crucial step in designing effective learning activities. In contrast to their counterparts in Hong Kong, English teachers in Mainland China appeared to shoulder a higher degree of responsibility in facilitating students' English learning, a perspective aligned with Confucian values.

Teleology

Teleology, within the context of curriculum analysis, delves into the overarching, long-term objectives of the curriculum, providing answers to the fundamental question of "what is to be achieved." Both Mainland China's curriculum and the Hong Kong curriculum share common goals related to language proficiency and cultural awareness. These shared objectives underscore the universal significance of these competencies in the realm of English language education, yet they manifest in distinct ways in each curriculum, unveiling significant differences in political orientations and cultural emphases.

Both curricula place a strong emphasis on the development of language proficiency as one of the most important goals. This emphasis is evident in Mainland China's curriculum where the core competency of "Language ability" is positioned as “foundation for developing the English subject core competencies” (MOE, 2017, p. 4). It is seen as the gateway to cross-cultural communication and the broader application of English skills. In the Hong Kong curriculum, language proficiency aligns with the "Interpersonal Skills" Strand, focusing on effective communication for various purposes, such as “study, work, leisure and persona enrichment” (CDC, 2015, p. 7). Cultural awareness is another shared objective. Both curricula recognize the importance of understanding and appreciating different cultures. Mainland China's curriculum explicitly mentions "cultural awareness" as a core competency, reflecting the significance of recognizing excellent cultures and fostering cross-cultural cognition (MOE, 2017, p. 4-5). The Hong Kong curriculum places cultural understanding as one of the five major aims, namely, to “further broaden their knowledge, understanding and experience of various cultures in which English is used”, highlighting the need for learners to gain a deeper appreciation of cultural diversity (CDC, 2015, p. 9).

While the shared objectives underscore common ground, significant differences emerge in how these goals are oriented and emphasized, revealing the unique societal and political contexts of Mainland China and Hong Kong. Mainland China's curriculum intertwines language proficiency and cultural awareness with an explicit national and political perspective. It underlines the development of "core socialist values," emphasizing the cultivation of students as "socialist builders and successors." (MOE, 2017, p. 5). The curriculum positions the English language as a tool for promoting values that align with the national ideology, emphasizing cross-cultural communication abilities in the context of globalization. In contrast, the Hong Kong curriculum focuses on practical language skills with orientations geared towards personal, academic, and vocational purposes with little relevance to the political dimension or national identity. It directly aligns with the socio-economic demands of the region. The "Strands" within the curriculum, particularly the "Interpersonal Skills" and "Experience" Strands, reflect an emphasis on applying language skills in real-life contexts to prepare learners for their future, whether it be in academic pursuits or the workforce (CDC, 2015, p. 7). These differences in orientation and emphasis are rooted in the distinct educational, political, and societal contexts of Mainland China and Hong Kong. Mainland China's curriculum is influenced by its overarching socialist ideology, while the Hong Kong curriculum is shaped by its unique socio-economic landscape, resulting in varying teleological perspectives within English language education.

Discussion

Analysing the ELT curricula in senior secondary schools in Mainland China and Hong Kong through the lens of critical governmentality reveals both similarities and differences. Commonalities between these regions include the central role of government authorities in shaping education policies and the rationalities that drive curriculum development. However, these shared elements are juxtaposed with variations in curricular priorities and levels of local autonomy, which can be attributed to a complex interplay of sociocultural, historical, economic, and socio-political factors.

Foucault's notion of governmentality refers to how governments, or in a broader sense, authorities, exercise control and power over the behaviours and practices of individuals and institutions (Dean, 2010). In this context, the curriculum can be regarded as a form of government because it reflects the values, ideologies, and priorities of the ruling authority, whether it is the Chinese Communist Party in Mainland China or the government in Hong Kong. The curriculum serves as a medium of "political socialization" (Almond & Verba, 1963) to develop the ideal citizen from the perspective of the government. Government authority and control are fundamental similarities in both Mainland China and Hong Kong. In Mainland China, the authority of the Communist Party significantly influences educational policies, while in Hong Kong, the government plays a pivotal role in curriculum development. This shared characteristic underscores the influence of governmentality (Dean, 2010), where the state's control remains a cornerstone in dictating curriculum design and implementation. It reflects how governments assert their power to govern and regulate educational institutions, processes, and outcomes in both regions. Parallel to this, a commonality arises in the rationalities that underpin curricula in Mainland China and Hong Kong. These guiding principles reflect government ideologies and values. In Mainland China, the curriculum reflects the government's emphasis on promoting socialist values, moral education, and patriotism, aligning with the broader ideological objectives of the Communist Party (MOE, 2017). Similarly, in Hong Kong, there is a focus on the development of language proficiency and global competitiveness, reflecting the region's economic and political priorities (CDC, 2015).

The curricula of Mainland China and Hong Kong exhibit commonalities, particularly in their emphasis on intercultural communication. These shared attributes can be predominantly traced back to the global nature of the English language in the post-colonial era (Adamson & Lai, 1997). English, as a global lingua franca, plays a pivotal role in international communication, transcending the confines of being merely a first or second language and extending its influence on countries where it is studied as a foreign language, such as China. Consequently, in both these regions, there is a growing societal expectation that English teaching and learning should not only prioritize linguistic proficiency but also encompass the development of intercultural competence for competition on a global level (Khan et al., 2019). The ongoing revisions in the curricula of Mainland China and Hong Kong are profoundly influenced by the global political and economic dynamics (Adamson & Morris, 1997; Cheng, 2011; Wang, 2007; Wang & Lam, 2009). The pedagogical shift toward communicative language teaching, which places communication at the core of language learning, is emblematic of the emphasis on intercultural communication skills. Furthermore, the curricula in both regions are informed by a competency-oriented approach, corresponding to the competency frameworks raised by global organizations like the European Commission (2019) and UNESCO (2016), where learning outcomes dictate the choice of teaching strategies and activities. This approach, when coupled with the global need for intercultural competence, directs education toward preparing individuals for success in an interconnected and culturally diverse world.

Nonetheless, the distinct differences in curricular priorities and autonomy between Mainland China and Hong Kong can be attributed to a combination of historical, economic, and socio-political factors, which aligns with Yang's (2012) findings about the impact of social, cultural and historical factors. Mainland China's history, characterized by events such as the cultural revolution and significant political shifts mentioned in previous literature review (e.g., Adamson, 2004), has continued to inform the recent curricula that place a strong emphasis on party loyalty, socialist values, and patriotism. Conversely, Hong Kong's historical path, from its colonial legacy as a British territory to its handover to Chinese sovereignty in 1997, has moulded a pragmatic approach. This emphasis is geared toward economic prosperity and global competitiveness. The processes of industrialization, urbanization, and modernization, coupled with an awareness of political sensitivities (Kwong, 2015), have contributed to the curriculum's focus on practical language skills while avoiding overtly political content in Hong Kong. In summary, from the governmentality perspective, it becomes evident that while centralized government control and shared rationalities exist, differences in curricular priorities and autonomy emerge due to the intricate interplay of historical, economic, and socio-political distinctions between these two regions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study's comprehensive analysis provides a nuanced understanding of how the ELT curricula in Mainland China and Hong Kong are shaped by the interplay of sociocultural, political, and historical factors. The study's application of Dean's analytics of government theory and a social constructivist perspective contributes to the broader discourse on educational policy and curriculum development, highlighting the intricate relationship between curriculum design, governance, and cultural context. By considering the problematizations, rationalities, techne, and teleology of these curricula, this study adds valuable insights into the complex dynamics of English language education in these two regions, serving as a foundation for further research and policy development. This research contributes to our understanding of how educational policies and practices in language education are deeply embedded in the unique contexts of each region, ultimately impacting students' learning experiences and outcomes. As Dean notes, “for all its pretensions to neutrality or to technical or scientific status, and for all its liberal heritage, behind ‘policy’ stands a shadow of an omnipotent state, administration, or bureaucracy issuing detailed regulations of individual and collective life” (Dean, 2005, p. 260).

In conclusion, this study's comprehensive analysis of the ELT curricula in Mainland China and Hong Kong has shed light on the commonalities and distinctions influenced by sociocultural, political, and historical factors. The insights gained from this research contribute significantly to our understanding of how educational policies and practices are deeply embedded in the unique contexts of each region, ultimately impacting students' learning experiences and outcomes. Looking ahead, it is imperative to recognize that Hong Kong's curriculum may retain its uniqueness compared to other cities in China, but it may also face increasing influence from the central government of China. During the revision of this article, a recent document titled "Resource Materials on Implementing National Security Education in the Secondary English Language Curriculum" was released by the Education Bureau of Hong Kong in 2023. This document encourages English Language teachers in Hong Kong to incorporate aspects of national security education into their teaching, spanning both subject-specific and cross-curricular approaches. This approach aims to enhance students' understanding of national security while developing their language skills and fostering positive values and attitudes related to national identity and responsibility. Given the rapidly changing educational landscape, future research should continue to explore the evolving dynamics between central authority and local autonomy in curriculum design and implementation, as well as the implications of these changes on students' language proficiency, cultural awareness, and overall learning experiences. It is essential to adopt a multifaceted research approach, including interviews, observations, and longitudinal studies, to capture the dynamic nature of curriculum development and its real-world impact.

References

Adamson, B. (2004). China’s English: A History of English in Chinese Education. Hong Kong University Press.

Adamson, B., & Lai, W. A. (1997). Language and the Curriculum in Hong Kong: Dilemmas of triglossia. Comparative Education, 33(2), 233-246.

Adamson, B., & Morris, P. (1997). The English curriculum in the People’s Republic of China. Comparative Education Review, 41(1), 3-26.

Almond, G. A., & Verba, S. (1963). The civic culture: Political attitudes and democracy in five nations. Sage Publications.

Bandura, A. (2002). Social Cognitive Theory in Cultural context. Applied Psychology, 51(2), 269–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00092

Benson, P., & Patkin, J. (2014). Innovation in Hong Kong’s new senior secondary English language curriculum: Learning English through popular culture. In D. Coniam (Ed.), English Language Education and Assessment: Recent developments in Hong Kong and the Chinese mainland (pp. 3-15). Springer Singapore.

Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27-40. https://doi.org/10.3316/qrj0902027

Carless, D., & Harfitt, G. (2013). Innovation in secondary education: A case of curriculum reform in Hong Kong. In K. Hyland & L. L. C. Wong (Eds.), Innovation and change in English language education (pp. 172-185). Routledge.

Chan, C. L. W., & Leung, P. (2014). Chinese culture. In Springer eBooks (pp. 833–839). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_3416

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. SAGE Publications Limited.

Cheng, X. (2011). The ‘English curriculum standards’ in China: Rationales and issues. In A. Feng (Ed.), English Language Education Across Greater China (pp. 133-150). Multilingual Matters.

Curriculum Development Council (CDC) (2015). English Language Education Key Learning Area: English Language Curriculum and Assessment Guide (Secondary 4 - 6). https://www.edb.gov.hk/attachment/en/curriculum-development/kla/eng-edu/Curriculum%20Document/EngLangCAGuide_Nov15.pdf

Curriculum Development Council (2017). English language education key learning area curriculum guide (Primary 1 - Secondary 6). https://www.edb.gov.hk/attachment/en/curriculum-development/kla/eng-edu/Curriculum%20Document/ELE%20KLACG_2017.pdf

Dean, M. (2005). Policy. In T. Bennett, L. Grossberg, & M. Morris (Eds.), New keywords: A revised vocabulary of culture and society (pp. 258–260). Blackwell.

Dean, M. (2010). Governmentality: Power and rule in modern society (2nd ed). Sage.

Education Commission (2000). Learning for Life, Learning Through Life: Reform Proposals for the Education System in Hong Kong. https://www.e-c.edu.hk/doc/en/publications_and_related_documents/education_reform/Edu-reform-eng.pdf

Ellis, R., Skehan, P., Li, S., Shintani, N., & Lambert, C. (2019). Task-based language teaching: Theory and practice. Cambridge University Press.

European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, (2019). Key competences for lifelong learning, Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/569540

Fan, H. (2023). Winter is coming? University teachers’ and students’ views on the value of learning English in China. Review of Education, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3410

Flick, U., Von Kardoff, E., & Steinke, I. (2004). A companion to qualitative research. SAGE.

Fung, C. K. C. (2021). Colonial governance and state incorporation of Chinese language: the case of the first Chinese language movement in Hong Kong. Social Transformations in Chinese Societies, 18(1), 59-74.

Gao, Y. (2018). China’s Fluctuating English Education Policy Discourses and Continuing Ambivalences in Identity Construction. In A. Curtis & R. Sussex (Eds.), Intercultural Communication in Asia: Education, Language and Values. Multilingual Education, vol 24 (pp.241-261). Springer.

Hamilton, A., Jin, Y., & Krieg, S. (2019). Early childhood arts curriculum: a cross-cultural study. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 51(5), 698–714. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2019.1575984

Hu, J., & Gao, X. (2018). Hong Kong English Curriculum in the New Millennium. The TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching (pp. 1-7). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118784235.eelt0937

Hu, R., & Adamson, B. (2012). Social ideologies and the English curriculum in China: A historical overview. In J. Ruan & C. Leung (Eds), Perspectives on teaching and learning English literacy in China (pp.1-17). Springer Dordrecht.

Kan, F. L. F. (2010). The functions of Hong Kong’s Chinese history, from colonialism to decolonization. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 42(2), 263–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220271003599165

Khan, M., Waheed, M., Chengwen, H., Butt, T. M., & Ahmad, J. (2019). Development and Perspectives of English, as a Language of Instruction and Learning in Chinese Educational System. Asian Journal of Contemporary Education, 3(1), 28-35. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.137.2019.31.28.35

Kim, E., & Jeon, J. (2005). A comparative study of the national English curricula of Korea, China and Japan: Educational policies and practices in the teaching of English. English Teaching (영어교육), 60(3), 27-48.

Koh, A. (2015). Popular Culture goes to school in Hong Kong: A Language Arts curriculum on revolutionary road? Oxford Review of Education, 41(6), 691-710. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2015.1110130

Krashen. (1982). Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. E-Learning, 46(2).

Kwong, Y. (2015). The Dynamics of Mainstream and Internet Alternative Media in Hong Kong: A Case Study of the Umbrella Movement. International Journal of China Studies, 6(3), 273-295. https://ics.um.edu.my/img/files/kwong(1).pdf

Li, C. S. D., & Leung, W. M. (2020). 香港“两文三语”格局:挑战与对策建议. 语言战略研究 [Chinese Journal of Language Policy and Planning], 5(1), 46.

Li, D. C. (1999). The functions and status of English in Hong Kong: A post-1997 update. English World-Wide, 20(1), 67-110.

Li, D. C. S. (2018). Two decades of decolonization and renationalization: the evolutionary dynamics of Hong Kong English and an update of its functions and status. Asian Englishes, 20(1), 2-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13488678.2017.1415517

Liu, W. (2016). The changing pedagogical discourses in China: The case of the foreign language curriculum change and its controversies. English Teaching-practice and Critique, 15(1), 74-90.

Liu, W. C., Koh, C., & Chua, B. L. (2017). Developing thinking teachers through learning portfolios. In O.-S. Tan, W.-C. Liu, & E.-L. Low (Eds.), Teacher Education in the 21st Century: Singapore’s Evolution and Innovation (pp. 173–192). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3386-5_10

Liu, H., Yu, Z., Zhang, J., & Yao, P. (2021). The Transmutation Logic of China University Science and Technology Innovation System since the Founding of the Communist Party of China One Hundred Years Ago: Three-Chain Perspectives Led by Party-Building. Education Research International, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/3459401

Lu, C., & Yan, T. (2022). Revisiting Chinese Political Culture: The Historical Politics Approach. Chinese Political Science Review, 7(1), 160–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-021-00208-y

Miao, J. (2021). Understanding the soft power of China’s Belt and Road Initiative through a discourse analysis in Europe. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 8(1), 162-177. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2021.1921612

Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China (MOE) (2017). 普通高中英语课程标准 (2017年版) [English Curriculum Standards of Senior Secondary School (2017 Version)]. People’s Education Press.

National Foreign Studies Universities Collaboration Committee for Student Affairs. (2021, December 15). Telling China’s Stories Well: Training Foreign Language Storytellers for the New Era. https://elt.i21st.cn/article/17084_1.html

Nichols, S., & Cormack, P. (2001). Literacy for the future? Mapping literacy requirements of the senior secondary curriculum. Paper presented at the Australian Curriculum Studies Association, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory.

Pan, L. (2015). Language education in China: The Cult of English. In L. Pan (Ed.), English as a Global Language in China (pp. 1-15). Springer.

Schubert, W. (1986). Curriculum: Perspective, paradigm, and possibility. Macmillan.

Tong, Y. (2021). Understanding English Mania in China: Reflection and Inspiration. Humanities and social sciences, 9(2), 51-56. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.hss.20210902.13

Tong, A., & Adamson, B. (2013). Educational Values and the English Language Curriculum in Hong Kong Secondary Schools Since 1975. Iranian Journal of Society, Culture and Language. http://www.ijscl.net/article_1831_ba3bbb0bd5503b3e635d727d44996923.pdf

Tsang, C. L., & Isaacs, T. (2021). Hong Kong secondary students’ perspectives on selecting test difficulty level and learner washback: Effects of a graded approach to assessment. Language Testing, 39(2), 212-238. https://doi.org/10.1177/02655322211050600

UNESCO (2016). A Conceptual Framework for Competencies Assessment. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245195

Wang, Q. (2007). The National Curriculum Changes and Their Effects on English Language Teaching in the People’s Republic of China. In J. Cummins & C. Davison (Eds.), International Handbook of English Language Teaching, vol. 15. Springer.

Wang, Q. (2018). 《 普通高中英语课程标准 (2017 年版)》 六大变化之解析[An interpretation of the six major changes in English Curriculum Standards of Senior Secondary School (2017 Version)].China Foreign Language Teaching, 11(2), 11-19, 84.

Wang, Q., & Chen, Z. (2012). Twenty-first century senior high school English curriculum reform in China. In J. Ruan & C. Leung (Eds.), Perspectives on teaching and learning English literacy in China (pp. 85-103). Springer Dordrecht.

Wang, W., & Lam, A. S. (2009). The English language curriculum for senior secondary school in China: Its evolution from 1949. RELC Journal, 40(1), 65-82.

Wang, Y. (2022). English education and Double reduction policy in the post-pandemic China. In Proceedings of the 2022 5th International Conference on Humanities Education and Social Sciences (ICHESS 2022) (pp. 1392–1402). https://doi.org/10.2991/978-2-494069-89-3_160

Yang, L., Yang, Y., & Xue, M. (2013). 中国大陆, 香港, 台湾高中英语课程标准比较研究 [A comparative study of senior secondary school English curricula: Mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan]. Yunnan Socialism College Journal, (4), 206-208.

Yang, Y. (2012). 中国大陆, 香港, 台湾高中英语课程标准比较研究 [A Comparative Study of Senior Secondary School English Curricula: Mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan]. [Master’s thesis, Xi’an Foreign Studies University] China National Knowledge Infrastructure Dissertation Repository. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CMFD&dbname=CMFD201301&filename=1012051325.nh&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=nHnbnq7SHF2GAiqflqQMYP2_Vk56y22_f9uOwwEDlORyu6b2T1SUc-k3JApmyq6w

Yong, L. (2019). Analysis on the Reform of English + Humanistic Ideological and Political Curriculum Integration from the Perspective of Core Literacy. 1st International Education Technology and Research Conference (IETRC 2019), 318-322. Francis Academic Press.

Zhang, T. (2016). 中国大陆、香港与新加坡小学与初中英语课程标准对比研究[A Comparative Study of Primary School and Junior High School English Curricula: Mainland China, Hong Kong and Singapore]. (Master’s thesis, Shandong Normal University). Wanfang Data Dissertation Repository. https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/thesis/ChJUaGVzaXNOZXdTMjAyMDEwMjgSCUQwMTExOTAxMBoIcmdtYmhrdHM%3D

Zhao, J. (2016). The reform of the National Matriculation English Test and its impact on the future of English in China. English Today, 32(2), 38-44.

![]() ©2024 Xiaoli Su, Dorottya Ruisz and Xiao

Zhang. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy

and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform,

and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the

original work is properly cited and states its license.

©2024 Xiaoli Su, Dorottya Ruisz and Xiao

Zhang. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy

and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform,

and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the

original work is properly cited and states its license.