Vol 8, No 3 (2024)

https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.5665

Article

Future Teachers Conceptualizing Democracy in Pre-war Ukraine, in Palestine, and Norway: Five Dimensions and the wikied Democracy Conceptions

Ingrid Christensen

Norwegian Police University College/University of South-Eastern Norway

Email: ingrid.christensen@phs.no

Larysa Dahl Kolesnyk

University of South-Eastern Norway

Email: larysa.kolesnyk@usn.no

Sami Adwan

Arab American University

Email: adwan.sami@gmail.com

Tetiana Matusevych

Dragomanov Ukrainian State University

Email: t.v.matusevych@udu.edu.ua

Abstract

This article presents a qualitative study of future teachers' conceptions of democracy in Ukraine, Palestine, and Norway during a pre-war and pre-pandemic period. In recent years, there has been a noticeable decline in the understanding of the democratic concept and reduced engagement, particularly among youth, coinciding with an assumed global recession of democratic recession. However, democracy also evolves with societal developments, whereas education holds the mandate to renew democratic values in society. This study therefore aims to explore student teachers' own definitions of the democracy concept. Employing a grounded theory approach, we compare the written responses of 619 student teachers from Ukraine, Palestine, and Norway. The analysis reveals that despite different emphases, democracy is articulated along five dimensions: 1) political systems, 2) political culture, 3) values, 4) actions, and 5) actors. However, the study also indicates a striking finding: To our surprise, there were many identical responses across the data material, interpreted as wikied copy-paste responses, which indicate a distance and irony towards standardized democracy concepts. Consequently, democracy education is in a limbo between standardization and fostering new dimensions, whereas the teachers' tasks will be challenging in providing democracy concepts born anew for the next generation.

Keywords: Democracy and citizenship education, democracy conception, comparative education, Ukraine, Palestine, Norway

Introduction: The challenges of conceptualizing democracy and the role of education

This article presents an international comparison of the conceptions of democracy among future teachers in a pre-war context in Ukraine, in Palestine, and Norway. At this present moment, two of the participating countries are at war. Global ideals have faced threats due to war and conflict all over the globe and even within so-called stable democracies (Sant, 2019). Democracy represents a global hope and is considered a premise for peaceful coexistence, sustainable development, and societal diversity (United Nations, 2022). In the past decade, however, there has been a worldwide diversification of democracy and a so-called “democratic recession” (Schulz et al., 2018, p. 199; Diamond, 2021; Economist Intelligence, 2023).

Education is considered to play a crucial role in securing the ideals of democracy at local, national, and international levels (Council of Europe, 2022; Schulz et al., 2018). School authorities are not only supposed to provide subject knowledge about democracy but carry a broader mandate to ensure that students possess the attitudes, and skills necessary to become active democratic citizens. Higher education and teacher education programs are expected to play a significant role in shaping democratic citizens, requiring a high level of professional development and up-to-date conceptual knowledge (Biseth & Lyden, 2018; Eriksen, 2018; Tierny, 2021).

Yet, the world-wide and largest study on democracy in education, the International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS), displays a generally weak understanding of democracy and decreasing civic engagement among young people (IEA, 2023; Storstad et al., 2023). These findings make a contrast to the high standards of democracy as a central value for political stability and economic development. The results raise questions about the usefulness of the standards and concepts of democracy communicated in education today.

This study is a comparative case study exploring the future teachers' own conception of democracy in Ukraine, Palestine, and Norway, representing widely different contexts for democracy. Norway is one of few countries in the world counted as a 'stable democracy' (Stokke et al., 2019)[1] or a 'full democracy' (Economist Intelligence, 2023). Ukraine is categorized as a 'hybrid regime', having oriented itself towards Europe during the last decade. Yet now, during the present war, everything is put on hold and is under martial law. Democracy in Palestine falls now under the category of 'hard autocracy'. Palestinian territories have been split under different regimes of Fatah and Hamas, yet also the political system and elections become paralyzed by Israeli interference with core infrastructure and occupation (Oppenheim, 2021; Tveit, 2023).

The three countries in this study make up a contrasting case between three countries of widely different conditions for democracy development. They have one issue in common, though: they all have had a long-standing commitment to a vision of democracy that puts steadfast hope in education and its potential for developing democratic citizens (Ministry of Education [Palestine], 2017; Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, 2017; The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2017). In times of decreasing understanding of the democracy concept, studying future teachers' expressions of democracy can be critical. Their voices might reflect their own democratic experiences in school and society, their present understanding, as well as mediating future hopes – or despairs about democracy.

On this background, the study aims to explore and compare the conceptualizations of democracy among student teachers across three vastly different countries Ukraine, Palestine, and Norway. We seek to establish a discussion about the possible shared challenges in promoting democracy in education. The research question addressed in this article is therefore: How do future teachers in Ukraine, Palestine, and Norway conceptualize democracy?

Theoretical underpinnings of democracy conceptions in education

This study adheres to the field of Democracy and Citizenship Education (DCE). In education, democracy can be described as a topic of teaching social science, comprising forms and developments of political systems, laws, and regulations. However, a foundational thought in DCE establishes democracy as a more foundational value and carries a broad societal mandate, whereas education contributes to the formation of democratic citizens in and through education (Apple, 2004; Biesta, 2014; Dewey, 1916/1997; Westheimer, 2015). By 'formation', DCE directs the focus on the school's promotion of democratic citizens. Rather than seeing democracy as a typical subject knowledge in e.g., social science, democracy can be viewed as a value and a general competence across school subjects, involving critical thinking, solidarity, problem-solving, freedom of speech, diversity, tolerance, dialogue, etc. (Dewey, 1916/1997; 1980; Freire, 1996; Westheimer, 2015). Teaching about democracy as knowledge content alone will not fulfill the democratic mandate in education. Instead, many representatives of DCE see democracy as a process, whereas democracy is mediated in and through education (Biseth & Lyden, 2018).

However, the next question is how the normative ideals of democracy concepts should be implemented in education. One significant measure is to establish democracy as a standardized and internationally recognized knowledge content in education. Such standardization has been influential in the Reference Framework of Competencies for a Democratic Culture in education (Council of Europe, 2022), as well as in teacher education (Council of Europe, 2023). This framework offers a coherent and instrumental approach and comprises teaching, learning, and assessment of four key competencies: knowledge and critical understanding, values, attitudes, and skills.

However, other voices within DCE, such as those from the field of critical pedagogy, also argue that democracy concepts cannot be implemented top-down (Dewey, 1980; Giroux & Giroux, 2008; Mollenhauer, 1996). Values are not just delivered, they come into being through co-creation and lived experience. Dewey (1980, p. 139) states that “In the hands of the students, democracy has to be born anew every generation, and education is its midwife”. Democracy must be conceived of as an open-ended concept, with education playing a transformative role (Freire, 1996; Gandin & Apple, 2002). By open-ended, conceptualizations of democracy must be understood within the context of historical trends and can evolve (Davies & Lundholm, 2011). According to such an approach, democracy cannot be acquired through the 'right' teaching methods or as pre-defined content but must take the students' voices and critical perspectives into account. Democracy concepts are understood as social practices within a community, and they do not have fixed, definitive meanings. The conceptualization of democracy, then, has a particular interest, as the very content of democracy evolves through an examination of how it is articulated over time and in different contexts (Biesta, 2014; Sant, 2019; Tønder & Thomassen, 2005). Thus, critical pedagogy maintains that the concepts of democracy draw upon historical, political, and material conditions as well as discursive contexts. In this way, democracy is understood as a dynamic concept, and the students' own perceptions of democracy are of particular interest.

Within the DCE field, various empirical, qualitative studies explore how the democracy concept is defined from typical everyday descriptions. Several studies categorize the conceptualizations as either 'thin' or 'thick' democracy concepts in education (e.g., Biseth & Lyden, 2018; Lambert, 2022; Mathé, 2016; Zyngier, 2016). A major finding in these empirical studies indicates a prevalent 'thin' understanding of democracy, focusing on the knowledge content related to elections, governmental systems, and aspects of a liberal democracy. Many of these studies argue that there is a need for a 'thick' approach to democracy in education that can promote the values and the transformative potential of democracy (Gandin & Apple, 2002). This present study seeks to move beyond the somewhat rough distinction between thin and thick, for more elaborate empirical dimensions of the democracy concept. Exploring and comparing this democracy concept among student teachers across three vastly different countries, Ukraine, Palestine, and Norway, we seek to discuss contextual and shared challenges in promoting democracy in education.

Empirical contexts and research in pre-war Ukraine, Palestine, and Norway

Over the past two decades, Ukraine has undergone significant societal changes as a post-Soviet country, redirecting its focus toward the European community (Shyyan & Shyyan, 2023). Recent empirical research in pre-war Ukraine has primarily pivoted around the challenges of implementing civic education within a strong system of public education (e.g., Fediy et al., 2021). Several initiatives have developed national programs for democratic schools, aiming to raise awareness of democracy (The European Wergeland Center, 2021). However, until 2015, there was limited emphasis on aspects like active citizenship, personal responsibility, civic participation, or tolerance towards other viewpoints, nations, ethnicities, and cultures (Kovalchuk, 2015), leaving democracy education a relatively new field of research.

In 2017, the national curriculum in Ukraine introduced the promotion of civic competencies across all subjects through the interdisciplinary theme of Civil Responsibility (Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, 2017). Additionally, in 2019, an interdisciplinary subject titled “I explore the world” was introduced based on dialogical learning methods (Andrusenko, 2019). Programs for implementing democracy education in schools have gained significant international attention, drawing inspiration from models proposed by the Council of Europe and the OECD's 21st-century skills framework (Kolesnyk & Biseth, 2024; The European Wergeland Center, 2021).

Empirical research on democracy conceptions in Ukrainian education and teacher education is relatively limited. However, a study by Matusevych and Kolesnyk (2019) indicates that while visions of democracy in teacher education are strong, student teachers predominantly exhibit a focus on thin democracy concepts related to teaching about government systems rather than value-based and thick democracy teaching. Other recent studies in Ukrainian teacher education explore the use of dialogue and collaborative change as a means of promoting democracy (Helskog, 2019; Matusevych & Kolesnyk, 2019).

In Palestine, education is significantly influenced by the ongoing conflict and the Israeli occupation. The Ministry of Education in Palestine manages public schools, with international funding playing a crucial role in shaping education policy and teacher development projects (Itmazi & Khlaif, 2022). Democratic citizenship is explicitly emphasized in the recent national curriculum for primary schools, aligning with international standards (Ministry of Education [Palestine], 2017). Laws and regulations governing education in Palestine, including teacher education, also emphasize democracy and democratization processes (Ministry of Education [Palestine], 2017). However, the presentation of political participation and equality principles and related explanatory concepts varies across subjects and lacks systematic integration. Civic, Islamic, and Arabic subjects prioritize these principles to differing degrees, with Civic subjects having the highest priority (Jalamna, 2016). Empirical studies are scarce on democracy in education and teacher education, including studies on conceptualizations of democracy in Palestine. Nevertheless, as a country under siege, issues of citizenship and human rights remain constant sources of attention (Hashweh, 2021).

Norway is widely recognized as one of the most stable democracies in the world (Freedom House, 2022) with a robust public welfare society and educational system. Democracy and citizenship have played central roles in Norwegian education throughout the last century, and recently, they have been introduced as interdisciplinary topics to be integrated into all school subjects (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2017). Empirical studies on DCE have been conducted in Norwegian schools (e.g., Eriksen, 2018; Huang et al., 2016; Stray & Sætra, 2017), as well as in teacher education programs (e.g., Biseth & Lyden, 2018; Mathé, 2016; 2019).

There are a few international comparative empirical studies on democracy in education. One example is the International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS), which conducts a comprehensive worldwide survey every 7-8 years among 16-year-old students from 22 European countries and selected countries in Asia and Latin America. The tendency from the ICCS 2016 and 2022 proves a significant decrease in the understanding of concepts of democracy on a global basis (Schulz et al., 2018; 2022). Another smaller comparative study is the Global Doing of Democracy Research Project (GDDRP), exploring the concept of democracy among student teachers and educators in over 25 countries. The project examines perspectives and perceptions of democracy in teacher education in various countries in Europe, Asia, Latin America and Oceania (Zyngier et al., 2015). The project consists of nationally adjusted surveys and contains only a few international comparative studies. Both ICCS and GDDRP studies have limited representation of East European contexts (only one country), and Middle Eastern countries were not included in either of the international comparisons. The present study aims to explore and compare democracy concepts among future teachers across three vastly different countries of Ukraine, Palestine, and Norway, displaying contextual and possible shared challenges in promoting democracy in education.

Methods: A grounded theory approach to democracy conceptualization

Given the varied practices of democracy and the apparent decline of democracy understandings, we seek not top-down 'checks' about the correct understanding of democracy. Instead, assuming that democracy also is lived practice (Dewey, 1916/1997), we take a grounded theory methodological approach (Charmaz 2006; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). We aim to develop conceptual categories through grounded theory analytical methods, then by comparing these categories' emphasis across the contexts of Ukraine, Palestine, and Norway. A grounded theory approach is inherently inductive and forwards the idea that society, reality, and self are constructed through interaction and rely on language and communication (Charmaz, 2006, p. 7). Grounded theory is not a theory in the sense that it offers predefined categories of what democracy is or should be. Neither is it theory-free, as it also rests on basic assumptions of epistemology and how to acquire knowledge. Grounded theory is a methodological approach for a research design facilitating the analysis of how democracy is formulated by the student teachers themselves and analyzing the responses inductively. Thus, we seek to avoid predefined and fixed categories of democracy conception and instead seek to explore its varied emphasis and interpretation across the contexts of Ukraine, Palestine, and Norway.

This study has a comparative case design with the starting point in exploring the theoretical construct of democracy (Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017). A comparative case study seeks to “disrupt dichotomies, static categories, and taken-for-granted notions of what is going on” (Bartlett & Vavrus 2017, p. 10). Data were collected from Ukraine, Palestine, and Norway. Using a purposeful, qualitative sampling strategy of maximum variation (Patton, 1990, p. 172), we expected a rich variation of democracy definitions between the countries and across teacher education programs in different regions in each country. Instead of establishing comparisons as national or regional profiles, we sought democracy as a rich phenomenon across sites (Bartlett & Vavrus 2017, p. 6), pursuing conceptual saturation rather than statistical representativeness or generalization (Flyvbjerg, 2011).

In Ukraine, we obtained a sample of n=274 student teachers from 110 teacher education programs in vocational teacher education colleges and universities. In Palestine, a sample of n=205 student teachers were collected from six pedagogical universities that offered bachelor's degrees, master's degrees, or diplomas in teaching. In Norway, a sample of n=140 student teachers were obtained from 18 teacher education institutions. The students participated voluntarily and by invitation via email, distributed by the administration of each teacher education program. The links in the email lead to survey forms where name/email/other identity marks were anonymized; in Norway through the standard university Nettskjema, and in Palestine and Ukraine through Google Forms.

The study explores the written responses to one open-ended and qualitative question: “How do you define democracy?” We intended to be clear and concise while leaving space for the student teachers to include contextual differences. Using a structured content analysis (Silverman, 2016), we employed partly the software NVivo and then Excel for qualitative coding. Thematic codes emerged when finding frequent terms. For instance, terms like “decide”/“choose,” and “participate” could denote a general category of “action.” These codes were then counted and presented in a table. The percentages were categorized into four frequency groups. In Table 1, the first column shows a relative percentage adjusted to the number of respondents in each country. The second column shows the qualitative description of emphasis and distribution of the thematic codes, such as “little” or “notable” emphasis, marked with color markers.

Table 1. Relative emphasis of democracy concepts of analytical, relative percentage in each country.

|

Relative percentage adjusted to the number of respondents in each country |

Qualitative description of the emphasis and distribution of the thematic codes applied to each country |

|

0-5 % |

Little |

|

6-14 % |

Delimited |

|

15-29 % |

Notable |

|

30 % and above |

High |

None of the terms in the data material exceeded a 61 % frequency. We approach the responses cautiously, seeing them as potential comprehensive and meaningful signifiers (Walton & Boon, 2014) of democracy as a social practice. Even modest occurrences, such as 10 % of responses, may carry meaningful information. Our approach to interpreting the data focuses on frequency but prefers a qualitative method rather than a statistical one. In the results section, we show how student teachers emphasize democracy, categorized as “little,” “delimited,” “notable,” and “high” emphasis.

During the analytical process, surprising findings emerged. The responses from Ukraine and Norway displayed a significant number of more or less identical responses. This led us to recognize the need for a second qualitative analysis of the extent and degree of these identical responses, delving into reflections about the landscape surrounding it among future teachers.

Regarding concept validity, we emphasized formulating one single, concise, and straightforward question, “How do you define democracy”? and thus minimize potential uncertainty for the informants and address possible linguistic misunderstandings. The collected data in each country was translated into English by native-speaking authors and professional English translation services. The interpretation of the data underwent extensive collaborative discussions among all the authors in the light of possible Ukrainian, Palestinian, and Norwegian contexts, seeking valid interpretations and implications.

In the work for the replicability of the analysis, we employed an anonymized and collaborative coding approach using shared Excel tables, whereas excerpts of the data material were collected, discussed, and then assigned to an analytical code. All authors reviewed the coding process, ensuring transparency and space for discussions and refinements. By utilizing a collaborative coding analysis, we aimed to enhance the replicability of our study, enabling others to follow the same coding procedure and potentially achieve comparable results across the data sets.

The study might be limited by the absence of regulated distribution across regions or teacher education programs or a specification of the subject-specific backgrounds or ages of the respondents. While it is unlikely that these factors resulted in a nonresponse error in a quantitative sense, they may be relevant for a more comprehensive understanding of the findings (Mhajne et al., 2014). The study could have benefited from additional qualitative questions or a contextual group interview to explore more elaborate definitions and conceptualizations of democracy, along with examples from local or national contexts. Variations in data collection periods may challenge the study's external and temporal validity, raising concerns about dataset relevance based on timing (Munger, 2019). Responses and findings could differ in contemporary democratic contexts from the ongoing conflicts in Ukraine and Palestine. However, it's crucial to note that this qualitative study aims to capture democracy conceptions within a specific timeframe, primarily representing pre-war contexts, that might embrace long-term cultural development for concepts such as democracy.

The study obtained approval from the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (SIKT) as an anonymous questionnaire, not requiring the inclusion of identity, affiliation, or other sensitive data. In the case of Ukraine and Palestine, where there is no specific quality assurance instance for research, the same ethical guidelines for data management and privacy as the Norwegian study have been applied. This ensures that data handling and privacy protection are approached consistently across all countries involved in the study.

Results: Five dimensions of democracy concept and a wikied response

In the following sections, we will outline the conceptualizations of democracy as defined by student teachers in Ukraine, Palestine, and Norway. The findings do not mirror any pre-defined categories but show a model of actual dimensions that the student teachers emphasized. First, we will present the various dimensions of the content within the democracy concepts and highlight the emphasis placed on these dimensions by student teachers in each country. In each section, we will briefly discuss the implications of the findings from Ukraine, Palestine, and Norway, offering insights into the understanding of democracy within these contexts. Additionally, we will analyze the response mode, examining how the students formulate their democracy concepts.

Exploring the dimensions of democracy conceptions of future teachers

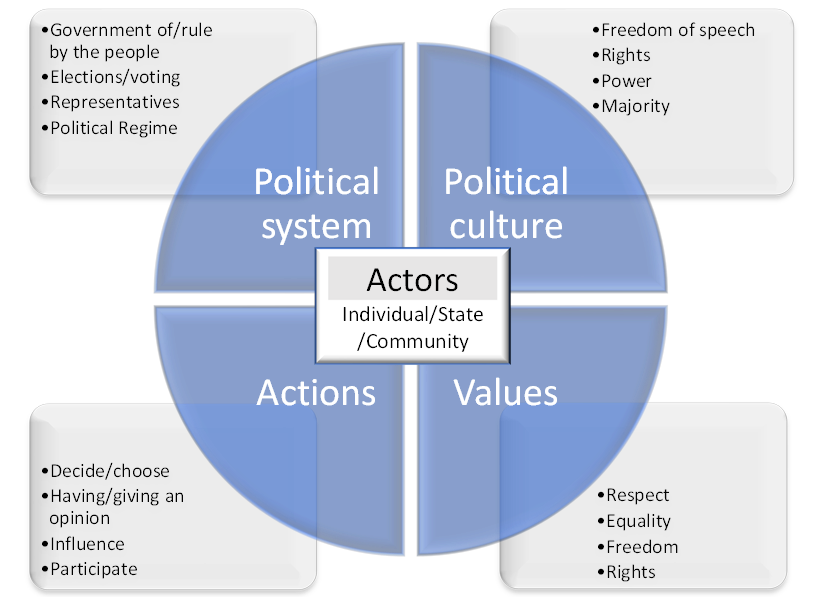

The content analysis of the responses revealed five overarching dimensions of democracy. These dimensions include student teachers' own phrases describing democracy as a political system, democracy as political culture, democracy as values, and democracy as actions. Actors were part of all the descriptions and, therefore, made up a fifth dimension. In Figure 1, these dimensions are shown along with examples of typical terms used by the student teachers:

Figure 1. A model of five dimensions of the democracy concept with frequent terms from the data material

We will present and provide brief commentary on each dimension of the democracy concept, highlighting how the respondents in each country emphasize different terms within these dimensions. We will also discuss some of the variations observed between the countries. The degree of emphasis will be indicated by relative frequency, categorized by color codes.

Dimension 1: Democracy as a political system

The dimension of democracy as a political system appears in terms like 'government of the people'/'rule by the people', 'elections', 'voting', 'representatives', and 'political regime'.

Table 2. Central terms of democracy as a political system and their emphasis in Ukraine, Palestine, and Norway

|

Emphasis among students

|

|||||||

|

|

Ukraine |

Palestine |

Norway |

||||

|

Government by the people, rule by the people |

|

|

|

||||

|

Government |

|

|

|

||||

|

Elections, voting |

|

|

|

||||

|

Representatives |

|

|

|

||||

|

Political regime |

|

|

|

||||

Democracy as a political system is a prominent dimension in the definition of democracy among student teachers in all three countries. The most used term in Norway and Ukraine is 'government/rule by the people', which is mentioned by only a few Palestinian respondents. The term 'government' has a high response rate across all countries. Ukrainian respondents specifically utilize the term 'political regime', while its usage is comparatively lower in Norway and Palestine. Norwegian student teachers generally employ a more varied and elaborate vocabulary for democracy as a political system than in Ukraine and Palestine.

The differences observed in the emphasis on democracy as a political system among Norwegian, Ukrainian, and Palestinian student teachers can be explained by historical and contextual factors to a certain degree. As a long-standing independent country, Norway has a well-established governmental order that dates to the Constitution of 1814. The Constitution has played a pivotal role for narrative of the creation of an independent nation-state. Through the Constitution, important democratic laws and systems were also initiated and gradually developed into what is now counted a stable and strong democracy. Norway now displays a general high level of trust in its government and electoral processes (Freedom House, 2022). These factors likely contribute to a strong emphasis of democracy as a political system among the Norwegian student teachers.

On the other hand, Ukraine has experienced a more complex political landscape, characterized by hybrid and fragile democracy systems. Nevertheless, democratic ideals are highly valued in Ukraine (President of Ukraine, 2021). Despite the absence of parliamentary elections in Palestine since 2007, Palestinian education laws and regulations acknowledge the need for systematic efforts in developing democracy (Ministry of Education [Palestine], 2017; Oppenheim, 2021). These contextual factors may contribute to the emphasis placed by Ukrainian and Palestinian student teachers on democracy as a political system, even in the face of challenges and limitations. While the historical, political, and contextual factors may explain the variations in emphasis, it is important to note that democracy as a political system remains a significant dimension in the conceptualization of democracy by student teachers in all three countries.

Dimension 2: Democracy as a political culture

Democracy as political culture encompasses key elements in the data material such as “freedom of speech,” “rights,” “power,” and “majority.” These terms exemplify the cultural aspects of democracy and are the product of historical and cultural developments within society (Balkin, 2016).

Table 3. Central terms labelled democracy as culture and their emphasis in Ukraine, Palestine, and Norway

|

Emphasis among students

|

|||||||

|

|

Ukraine |

Palestine |

Norway |

||||

|

Rights |

|

|

|

||||

|

Power |

|

|

|

||||

|

Majority |

|

|

|

||||

|

Freedom of speech/expression |

|

|

|

||||

The three countries emphasize terms related to political culture in significantly different ways. In Palestine, the most used terms in the entire Palestinian dataset are freedom of speech and freedom of expression, along with mentions of rights. In the Norwegian dataset, there is a notable emphasis on rights, while a notable part of Norwegian respondents stresses the term majority. Surprisingly, power and freedom of speech/expression receive comparatively little attention. In Ukraine, the concept of democracy as a cultural aspect is given little conceptual emphasis, except for the term power.

The Palestinians put strong emphasis on the cultural dimension and the term freedom of speech can be attributed to their status under siege, strict surveillance, and the desire to be heard in the international community. Additionally, Palestine demonstrates a generally high level of engagement in political organizations (Oppenheim, 2021). The term rights also receives attention in the data material. In Norway, the focus on majority may reflect a belief in the influence of citizens within a well-functioning political system. As for Ukraine, the limited emphasis on rights or freedom of speech could be connected to its history as a post-Soviet country with a history of authoritarian rule. However, the issue of power appears to be important to a small number of students.

Dimension 3: Democracy as a value

Democracy is also described as values by the informants and can be exemplified in terms like respect, equality, freedom, and rights that, according to Franck (2020), are connected to democratic values.

Table 4: Central terms labeled democracy as values and their emphasis in Ukraine, Palestine, and Norway

|

Central terms labelling democracy as values |

Emphasis among students

|

||||||

|

|

Ukraine |

Palestine |

Norway |

||||

|

Freedom |

|

|

|

||||

|

Respect |

|

|

|

||||

|

Rights |

|

|

|

||||

|

Equality |

|

|

|

||||

Among Palestinian student teachers, the dimension of values stands out as the most prevalent and elaborated aspect when defining democracy. More than half of Palestinian respondents mentioned the term respect, highlighting its importance. The term freedom was also prominent, while rights and equality remained notable themes. In Norway, there is a specific emphasis on the value dimension, particularly the term rights. In comparison, the value dimension of democracy in Ukraine is relatively low compared to the other two countries.

In Palestine, democracy appears to be less of a concept for a system and more of a deeply ingrained value, representing assumptions, hopes, and formal values within the country's education strategies (Ministry of Education and Higher Education [Palestine], 2017). The values of freedom, respect, and rights are crucial issues in Palestine's occupation and conflict with Israel, and they serve as cornerstones for Palestine's legitimacy as a state and its international support from organizations such as the United Nations and major global society organizations (e.g., the United Nations, 2022). The very existence of democracy then seems to rest precisely on the ideas and values of freedom and human rights.

The emphasis on freedom and rights in the Norwegian results may reflect its position as one of the leading countries in terms of freedom worldwide, often advocating for and taking pride in its role in promoting human rights (Freedom House, 2022). However, concepts such as respect or equality are surprisingly not established as integral components of democracy. Although the Ministry of Education in Ukraine also highlights these values (Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, 2017), Ukrainian student teachers do not appear to be particularly preoccupied with them. One possible explanation is that Ukrainian student teachers may place more emphasis on individual opportunities rather than collective values and virtues (Borysenko, 2017).

Dimension 4: Democracy as actions

Respondents had several descriptions of actions and activities in their descriptions of democracy, labeled 'democracy as action', which can be connected to Dewey's elaborations of action in democracy education (Dewey, 1916[1997], p. 88).

Table 5. Central terms labeled democracy as action, and their emphasis in Ukraine, Palestine, and Norway

|

Central terms labeling democracy as actions |

Emphasis among students

|

||||||

|

|

Ukraine |

Palestine |

Norway |

||||

|

Influence* (influenced, influencing) |

|

|

|

||||

|

Opinion |

|

|

|

||||

|

Decide/choose (decision, decision-making) |

|

|

|

||||

Among Norwegian student teachers, democracy as an active process has received significant attention. Most students in Norway describe democracy as a means of making decisions or participating in decision-making processes. Having influence and expressing one's opinion are also notable aspects within the Norwegian dataset. In Palestine, about a third of the student teachers emphasize the expression of their own opinion, while being involved in decision-making holds some importance. Democracy receives minimal attention in terms of actions among Ukrainian student teachers.

In Norway, there is a high emphasis on engagement in decision-making, influencing outcomes, and sharing and expressing opinions are considered crucial actions within a democracy. While Norway has a representative electoral system at the national level, local democracies provide children and young people with numerous rights and opportunities through student councils and various political youth organizations, and a focus on active citizen and student-centered learning in the Norwegian school curricula throughout the last century (Løvlie, 2022). Among Palestinian student teachers, there is a notable emphasis on expressing opinions, which aligns with their active participation in political grassroots movements (Mhjane, 2017). In Ukraine, the repertoire for democratic action receives minimal emphasis. This could be attributed to the prevalence of corruption, which appears to engender passivity and hopelessness among young people (Vollmer & Malynovska, 2016). The passivity of Ukrainian youth has been a longstanding issue for the Ukrainian state, characterized by low civic and political activity and limited access. Post-Soviet values and a lack of trust in state institutions remain significant challenges for youth participation and civic engagement in Ukraine (Council of Europe, 2019).

Dimension 5: Democracy actors

The descriptions of democracy also encompass the identification of responsible and active participants. This aspect forms the dimension of 'democracy actors', which includes descriptions of the individual, the state, and the community. This dimension provides insights into the diverse forms and conditions of democracy while also serving as an indicator of student agency (Biesta, 2011).

Table 6. Central terms labeled 'democracy actors' and their emphasis in Ukraine, Norway, and Palestine

|

Central terms labelling democracy actors |

Emphasis among students (in %)

|

||||||

|

Ukraine |

Palestine |

Norway |

|||||

|

Individual/self |

|

|

|

||||

|

State |

|

|

|

||||

|

Community |

|

|

|

||||

In the Ukrainian data material, the most prevalent actor mentioned is the state, which is a huge contrast to the almost absent mentions in Palestine and Norway. In Palestine, the individual or self was mentioned in 19% of responses, indicating a stronger focus on individual agency. In contrast, there is little emphasis on actors as such in the Norwegian data.

The dominance of the state as an actor in the Ukrainian sample can be explained by its historical context as a former Soviet state and its association with a subdued, collectivist, and communist culture. Additionally, the state plays a significant role in recent civic and patriotic movements (Shore, 2018). However, it is important to note that Ukrainian culture has historically been considered individualistic and independent (Borysenko, 2017, p. 60), although this aspect does not appear prominently in the current data material.

The emphasis on the individual among Palestinian student teachers is indeed surprising, considering that Arab culture is generally regarded as more collectivist than individualistic (Weishut, 2020, p. 93). However, one could interpret the results as an expression of individual responsibility or individual agency. This may be influenced by the perceived inefficiency of governmental parties and the increasing grassroots activism within Palestine (Weishut, 2020).

On the other hand, Norwegian student teachers do not place particular emphasis on any specific actor. One could possibly infer that Norwegian students do not strongly advocate for any predefined role in terms of either the community or the individual. Alternatively, they may present more objectified notions of democracy.

A discouraging finding: The wikied turn of the democracy concept

When exploring the democracy conceptualization among student teachers, a discouraging finding was revealed in the process, that might raise doubts about the former findings: It was observed that many of the students tend to give identical, or maybe duplicated responses, particularly evident in the Ukrainian dataset. Many of the Ukrainian responses are identical, with some variations. The question “How do you define democracy?” seems to generate two types of identical answers among the 274 Ukrainian informants:

1. “The political regime in which the people are recognized as the only source of power in the state”, is a response from a total of 30 Ukrainian student teachers.

2. Democracy is also defined as “the form of the political organization of society, characterized by the participation of the people in the management of the state” by a total of 31 Ukrainian respondents.

Only a few answered more individually, making up exceptions to the general tendency: Democracy is “... your own thoughts […] expression, feeling comfortable in the environment we are in, respect, and mutual understanding”.

However, it should be noted that the tendency to provide standardized responses may also be present among Norwegian students. They often offer brief and automated descriptions of democracy, with the phrase “Government by the people” appearing 35 times and accounting for one-fourth of the responses. Many of these responses lack further explanation or elaboration. In contrast, Palestinian student teachers do not provide standardized responses and tend to offer more diverse and freely defined descriptions of democracy.

This observation suggests a tendency towards a 'copy-paste' practice in conceptualizing democracy, resulting in what can be referred to as wikied responses. In the following section, we will reflect upon these discouraging responses along with the dimensions of democracy and discuss some conditions for the democracy concept in the field of DCE.

Challenging democracy education in times of democratic recession

In this article, we have explored how future teachers in Ukraine, Palestine, and Norway conceptualize democracy. The present study aims to explore and compare democracy concepts among future teachers across three vastly different countries, displaying contextual and possible shared challenges in promoting democracy in education. The recent development of the war in Ukraine and Palestine creates difficulties in even speaking about democracy. Yet, the decline of democracy and increasing political tensions and wars place additional pressure on institutions like education as a space for developing democracy in safeguarding peace and stability.

The analysis shows the emergence of five distinct dimensions of the democracy concept, namely 1) political system, 2) political culture, 3) values, 4) actions, and 5) involved and responsible actors. An overall, and less surprising finding across the three countries is a general emphasis on democracy as a governmental system. The study shows also national variations, whereas Ukrainian student teachers predominantly describe democracy as a political system and emphasize power and highlight the state as the major actor of democracy. Palestinian student teachers place a strong emphasis on democracy as sets of values and a political cultural concept, highlighting values such as freedom, respect, equality, and freedom of speech. They consider the individual, not the state or the society, as a major actor. Many Norwegian student teachers express varied conceptions of democracy, with a particular focus on democracy as a political system and underline the concept of democracy in terms of actions and participation.

Despite the emergence of new dimensions in the democracy concept, the study also uncovers a highly problematic and ironic finding in Ukraine and Norway: a significant number of future teachers provide identical, copy-paste formulations. We refer to these findings as wikied responses. On the one hand, one could conclude that the findings would undermine the trustworthiness of the data. The very findings in this present study both confirm and challenge former studies. The respondents in this present study emphasize democracy as knowledge about governmental systems, showing a similar thin understanding of democracy in education (Biesta, 2014; Biseth & Lyden, 2018; Mathé, 2016; Matusevych & Kolesnyk, 2019; Zyngier et al., 2015). Many former studies in DCE describe the core challenge of a weak and so-called thin understanding of democracy in school. The repeated and identical wikied responses in this study can reinforce the impression that democracy is understood as a thin democracy concept. A thin understanding of democracy can have problematic consequences, such as reinforcing reproductive learning patterns (Montuori, 2012), detaching democracy from its context (Gandin & Apple, 2002), and hindering the development of student agency (Biesta, 2014).

However, there are reasons to problematize the possible discouragements of this present study. The grounded theory analysis displays democracy as a multidimensional concept. It indicates the existence of alternative versions of the concept of democracy. The findings are not only evaluated as thin and a lack of fulfilling standards (Tønder & Thomassen, 2005) but might work to establish nuanced additions to the concept. For example, Palestinian student teachers place a strong emphasis on values in education, representing an explicit thick approach to the democracy concept. Terms like freedom of expression do not only describe the ideal of democracy but also reflect the daily challenges and tensions they face, whereas the lack of freedom of expression is prevalent. The Norwegian student teachers emphasize democracy as actions, providing a nuanced perspective that challenges previous notions of a thin democracy conceptualization among Norwegian student teachers.

The seemingly disappointing wikied and copy-paste responses in Ukraine and Norway also offer an intriguing insight: What if these responses communicate more than passive repetitions? Perhaps these students perceive democracy as what Laclau and Mouffe (1985/2014) would describe as an empty signifier—a symbol that has lost its meaning but remains impossible to define, defend, or develop. The repetition and copy-pasting can be interpreted as discursive nodal points (Jacobs & Tschötschel, 2019) of a democracy that does not work. The wikied responses could be seen as a subversion, where student teachers mock, invert, and highlight the irony of established and non-working standardized democracy ideals.

Bartlett and Vavrus (2017) describe comparative case studies as a means of producing a “sense of shared place, purpose or identity with regard to the central phenomenon” (p. 10). Handling the concept of democracy in education has turned out to represent a dual and shared challenge: balancing democracy as a standardized definition, while also stirring the critical voices of students. In times of a democratic recession, it may seem like settled definitions and even standardized international frameworks fail. Therefore, this paper might represent a call for studies that explore bottom-up and open-ended definitions of democracy further (Tønder & Thomassen, 2005). Open-ended conceptions, however, do not mean that anything goes. This study represents a case for diversified conceptions of democracy, taking in its failures, weaknesses, and otherings. There is a need for more elaborate studies to support future teachers in exploring new concepts of democracy, as their tasks as midwives for future democracy are anything but simple.

References

Andrusenko, I. V. (2019). Integrated course "I explore the world" in a new Ukrainian school. In Pedagogical Comparative Studies and International Education—2019: Internationalization and Integration in Education in the Context of Globalization (pp. 89-91). Proceedings of the 3rd International Scientific and Practical Conference, May 30, 2019, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Apple, M. W. (2004). Ideology and curriculum (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203487563

Balkin, J. M. (2016). Cultural Democracy and the First Amendment. Northwestern University Law Review, 110(5), 1053-1096.

Bartlett, L. & Vavrus, F. (2017). Comparative Case Studies: An Innovative Approach. Nordic Journal of International and Comparative Education, 1(1),5-17. http://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.1929

Biesta, G. (2011). The Ignorant Citizen: Mouffe, Rancière, and the Subject of Democratic Education. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 30(2), 141-153.

Biesta, G. (2014). Utdanningens vidunderlige risiko. Fagbokforlaget.

Biseth, H., & Lyden, S. (2018). Norwegian Teacher Educators' Attentiveness to Democracy and their Practices. International Journal of Learning. Teaching and Educational Research, 17(7), 26-42. https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.17.7.2

Borysenko, L. H. (2017). Ukrainian culture: individualism or collectivism? Frontier problems of modern psychology [Conference proceedings]. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/a5j2c

(2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. Sage.

Council of Europe (2019). Youth sector strategy 2030. https://rm.coe.int/a5-brochure-youth-sector-strategy-2030-ukrainian/1680a0d1f3

Council of Europe (2022). Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture. https://www.coe.int/en/web/reference-framework-of-competences-for-democratic-culture

Council of Europe (2023). The conceptual foundations of the Framework. https://rm.coe.int/the-conceptual-foundations-of-the-framework-reference-framework-of-com/16809940c1

Davies, P., & Lundholm, C. (2011). Students' understanding of socio-economic phenomena: Conceptions about the free provision of goods and services. Journal of Economic Psychology: Research in Economic Psychology and Behavioral Economics, 33(1), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2011.08.003

Dewey, J. (1916/1997). Democracy and education. Dover Publications Inc.

Dewey, J. (1980). The Middle Works, 1899-1924. SIU Press.

Diamond, L. (2021). Democratic regression in comparative perspective: scope, methods, and causes. Democratization, 28(1), 22-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2020.1807517

Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Economist Intelligence (2023). Democracy Index 2023: Age of conflict. Economist Intelligence/EIU

Ermarth, E. D. (2001). Agency in the Discursive Condition. History and Theory, 40(4), 34–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/0018-2656.00181

Eriksen, K. G. (2018). Bringing Democratic Theory into Didactical Practice. Concepts of Education for Democracy Among Norwegian Pre-service Teachers. Interchange, 49(3), 393-409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10780-018-9332-7

The European Wergeland Centre (2021). Schools for Democracy. Supporting Educational Reforms in Ukraine Progress Report. https://theewc.org/resources/schools-for-democracy-progress-report/

Fediy, O., Protsai, L., & Gibalova, N. (2021). Pedagogical Conditions for Digital Citizenship Formation among Primary School Pupils. Revista Romaneasca Pentru Educatie Multidimensionala, 13(3), 95-115. https://doi.org/10.18662/rrem/13.3/442

Flyvbjerg, B. (2011). Making Social Science Matter: Why social inquiry fails and how it can succeed again. Cambridge University Press.

Franck, O. (2020). Ethics Education in Democratic Pluralist Contexts. Educational Theory, 70(1), 73-88. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12410

Freedom House (2022). Freedom in the world 2022, Norway. Freedom House.

Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Penguin.

Gandin, L., & Apple, M. (2002). Thin versus thick democracy in education: Porto Alegre and the creation of alternatives to neo-liberalism. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 12(2), 99-116. https://doi.org/10.1080/09620210200200085

Giroux, H. A., & Giroux, S. (2006). Challenging neoliberalism's New World Order: the promise of critical pedagogy. Cultural Studies, Critical Methodologies, 6(1), 21-32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708605282810

Glaser, G. B., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Sociology Press

Hashweh, M. Z. (2021). Conflict and Democracy Education in Palestine. Mediterranean Journal of Educational Studies, 7(1), 65-86.

Helskog, G. (2019). Democracy education the Dialogos Way: The case of the Ukrainian teacher education. Професіоналізм педагога: теоретичні й методичні аспекти, (11), 5-28. https://doi.org/10.31865/2414-9292.11.2019.197207

Huang, L., Ødegård, G., Hegna, K., Svagård, V., Helland, T., & Seland, I. (2016). Unge medborgere. Demokratiforståelse, kunnskap og engasjement blant 9.- klassinger i Norge, The International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS) 2016. NOVA-rapport 15/17.

IEA (Nov 28, 2023). IEA Releases Latest Results of the International Civic and Citizenship Education Study, ICCS 2022. IEA ICCS 2022 International Press Release.pdf

Itmazi, J., & Khlaif, Z. N. (2022). Science Education in Palestine. In R. Huang, B. Xin, & A. Tlili (Eds.), Science Education in Countries Along the Belt & Road: Future Insights and New Requirements (pp. 129-149). Springer.

Jacobs, T., & Tschötschel, R. (2019). Topic models meet discourse analysis: A quantitative tool for a qualitative approach. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 22(5), 469-485. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2019.1576317

Jalamna, S. H. (2016). Evaluating the Content of Civic Education, Arabic and Islamic Education Curricula in Palestine in the Higher Elementary Stage in light of Citizenship Principles [Master's thesis]. Birzeit University.

Kolesnyk, L. & Biseth, H. (2024). Professional development in teacher education through international collaboration: when education reform hits Ukraine. Professional Development in Education, 50(2), 347–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2023.2193197

Laborin, M. B. (2011). Mock democracies: Authoritarian cover-ups [Review essay]. Journal of International Affairs, 1(65), 254-256.

Lambert, J. M. (2022). Defining citizenship and democracy: A Delphi study. Journal of Social Studies and History Education, 6(1), 1-23.

, & (1985/2014). Hegemony and socialist strategy: Towards a radical democratic politics (3rd ed.). Verso

Løvlie, L. (2022). Akademisk dygd og politikkens fravær. Nordisk tidsskrift for pedagogikk og kritikk, 8, 29–33. http://dx.doi.org/10.23865/ntpk.v8.3755

Mathé, N. E. H. (2016). Students´ Understanding of the Concept of Democracy and Implications for Teacher Education Social Studies. Acta in Didactica, 10(2), 271-289. https://doi.org/10.5617/adno.2437

Mathé, N. E. H. (2019). Democracy and politics in upper secondary social studies: Students' perceptions of democracy, politics, and citizenship preparation [PhD Dissertation]. University of Oslo.

Matusevych, T. & Kolesnyk, L. (2019). Democracy in education: an ideal being or a pedagogical reality? Філософія Освіти, 24(1),115-127. https://doi.org/10.31874/2309-1606-2019-24-1-115-127

Mhajne, A. (2017, September 12). Political Space for Israel's Palestinians? Sada/Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Ministry of Education [Palestine] (2017). Palestinian Law for Education and Higher Education. https://www.wattan.net/data/uploads/bafce6842e81cbbeac9fd6a7f5a5dfdd.pdf

Ministry of Education and Higher Education [Palestine] (2017). Education sector and strategic plan 2017-2022. https://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/sites/default/files/ressources/palestine_education_sector_strategic_plan_2017-2022.pdf

Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine. (2017). New Ukrainian school. https://mon.gov.ua/eng/tag/nova-ukrainska-shkola (Accessed 16 May 2020).

Mollenhauer, K. (1996). Glemte sammenhenger. Om kultur og oppdragelse. Ad Notam Gyldendal.

Montuori, A. (2012). Reproductive Learning. In N. M. Seel (Ed,), Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning (pp. 2838-2840). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_811

Munger, K. (2019). The Limited Value of Non-Replicable Field Experiments in Contexts With Low Temporal Validity. Social Media + Society, 5(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119859294

The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training (2017). Core curriculum – values and principles for primary and secondary education. https://www.udir.no/lk20/overordnet-del/?lang=eng

Oppenheim, B. (2021, April 23). Halting Palestine's Democratic Decline. Carnegie Europe. https://carnegieeurope.eu/2021/04/23/halting-palestine-s-democratic-decline-pub-84383

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research. Sage Publications.

President of Ukraine (2021, December 10). One of Ukraine's priorities is to uphold the values of freedom and democracy - President at the Summit for Democracy. https://www.president.gov.ua/en/news/odnim-iz-prioritetiv-ukrayini-ye-vidstoyuvannya-cinnostej-sv-71965

Sant, E. (2019). Democratic Education: A Theoretical Review (2006–2017). Review of Educational Research, 89(5), 655-696. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319862493

Schulz, W., Ainley, J., Fraillon, J., Losito, B., Agrusti, G., & Friedman, T. (2018). Main findings and implications for policy and practice. In W. Schulz, J. Ainley, J. Fraillon, B. Losito, G. Agrusti, & T. Friedman (Eds.), Becoming Citizens in a Changing World: IEA International Civic and Citizenship Education Study 2016 International Report (pp. 199-210). Springer International Publishing.

Schulz, W., Ainley, J., Fraillon, J., Losito, B., Agrusti, G., Damiani, G., & Friedman, T. (2023). Education for Citizenship in Times of Global Challenge: IEA International Civic and Citizenship Study 2022 International Report. IEA.

Shore, M. (2018). The Ukrainian Night. An intimate history of revolution. Yale University Press.

Shyyan, O., & Shyyan, R. (2023). Teacher Education in Ukraine: Surfing the Third Wave of Change. In M. Kowalczuk-Walędziak, R. A. Valeeva, M. Sablić & I. Menter (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Teacher Education in Central and Eastern Europe (pp. 527-551). Springer International Publishing.

Silverman, D. (2016). Qualitative Research. Sage.

Stokke, K., & Aung, S. M. (2019). Transition to Democracy or Hybrid Regime? The Dynamics and Outcomes of Democratization in Myanmar. European Journal of Development Research, 32, 274-293. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-019-00247-x

Storstad, O., Caspersen, J., Wendelborg, C. (2023). The International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS) 2022: Ett steg fram og to tilbake. Demokratiforståelse, holdninger og deltakelse blant norske ungdomsskoleelever. NTNU.

Stray, J., & Sætra, E. (2017). Teaching for democracy: Transformative learning theory mediating policy and practice. Nordisk tidsskrift for pedagogikk og kritikk, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.23865/ntpk.v3.555

Tierny, W. G. (2021). Higher education for democracy. State University of New York Press

Tveit, O. K. (2023). Palestina: Israels ran, vårt svik. Kagge Forlag AS.

Tønder, L., & Thomassen, L. (2005). Introduction: Rethinking radical democracy between abundance and lack. In L. Tønder & L. Thomassen (Eds.), Radical democracy between abundance and lack (pp. 1-13). Manchester University Press.

United Nations (2022, January 4). The questions on Palestine. https://www.un.org/unispal/committee/

Vollmer, B., & Malynovska, O. (2016). Research on Ukrainian Migration Before and Since 1991. In O. Fedyuk & M. Kindler (Eds.), Ukrainian Migration to the European Union (pp. 17-23). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41776-9_2

Walton, S., & Boon, B. (2014). Engaging with a Laclau & Mouffe-informed discourse analysis: A proposed framework. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 9(4), 351-370. https://doi.org/10.1108/QROM-10-2012-1106

Weishut, D. J. N. (2020). Intercultural Friendship: The Case of a Palestinian Bedouin and a Dutch Israeli Jew. Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004444003

Westheimer, J. (2015). What kind of citizen? Educating our children for the common good. Teachers College Press.

Zyngier, D., Traverso, M. D., & Murriello, A. (2015). “Democracy Will Not Fall from the Sky.” A Comparative Study of Teacher Education Students' Perceptions of Democracy in Two Neo-Liberal Societies: Argentina and Australia. Research in Comparative and International Education, 10(2), 275-299. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745499915571709

Zyngier, D. (2016). What future teachers believe about democracy and why it is important. Teachers and Teaching, 22(7), 782-804. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1185817