International Master’s Degree Students’ Experiences of Support at a Finnish University

Anduena Ballo

University of Jyväskylä

Email: anballo@jyu.fi

Sotiria Varis

University of Jyväskylä

Email: sotiria.s.varis@jyu.fi

Charles Mathies

Old Dominion University/ University of Jyväskylä

Email: cmathies@odu.edu

Kalypso Filippou

Umeå University/University of Turku

Email: kalypso.filippou@umu.se

Abstract

This phenomenographic study explores international master’s degree students’ ways of experiencing support in Finnish higher education. The study draws on Schlossberg’s Transition Model and the Culturally Engaging Campus Environments Model as a conceptual framework. The phenomenographic analysis of 17 interviews with international master’s degree students identified four ways of experiencing support as: (a) study system adjustment, (b) learning enhancement, (c) personal growth, and (d) autonomy development. The findings identified participants’ experiencing support in relationships, use of information, communication, services, the flexibility of studies, learning and study environments. The presence of two indicators, Humanizing Educational Environments and Availability of Holistic Support suggested that the campus environment was culturally responsive to academic and personal support of international degree students. The findings contribute to the understanding of support for international degree students in higher education and may be used to develop services to support international degree students’ social, cultural, and career integration into host communities.

Keywords: international degree students, support, experiences, phenomenography, Student Development Theory

Introduction

The rapid increase in competitiveness for global talent acquisition raises questions about whether Finnish higher education institutions are still attractive to international master’s degree students (IMDS)[1], and whether they stay in Finland after graduation. In Finland, IMDS in higher education institutions (HEIs) accounts for 8% of students, which is higher than the average 6% of OECD countries (OECD, 2019). Since 2001, the Finnish government has employed several internationalization strategies to recruit and integrate IMDS in Finland but the “country continues to face the same challenges of recruitment, employment and integration” (Jokila et al., 2019, p. 406). The number of annually enrolled international students, including master students and doctoral researchers, is lower in Finland than in other European countries (e.g., Denmark, Norway, and the Netherlands), but the stay rate of international students after graduation is higher (Mathies & Karhunen, 2021). The current internationalization strategy of Finland aims to attract and recruit three times as many IMDS and increase the stay rate up to 75% by 2030 (Finnish Government, 2021). It is seen as essential for Finland’s economic development and its fast-aging population that IMDS who graduate from HEIs remain in Finland and integrate into society (Centre for International Mobility, 2016). Hence, support to help IMDS integrate into Finland and the Finnish labor market is considered a priority (Finnish Government, 2021).

The notion of student support varies in understanding and interpretation among students, service providers, and HEIs. Contrary to a humanistic view emphasizing support towards students' academic learning and personal development, international student support is mainly perceived as therapeutical, whereby students are considered “a counseling case” and always in need of help (Bartram, 2009, p. 5). Although many scholars acknowledge the high experiential impact of studying abroad, they question whether support for international students’ academic success and personal development is considered a goal for HEIs (Glass & Holton, 2021; McKeown et al., 2021). Students’ success in higher education (HE) is often measured with quantifiable indicators like grades and completion rates, while other aspects (e.g., satisfaction with the study experience, integration, or appreciation of human differences) are difficult to measure but very important indicators of success (Kuh et al., 2005). Understanding student development in HE is central to providing effective support to students while facing changes, transitions, and making their journey meaningful (Anderson et al., 2022; Schlossberg et al., 1995). A considerable body of theories acknowledge the influence of campus environments on students’ success and integration into academic and social communities (Museus, 2014).

Research on experiences of support to IMDS is limited and mainly focused only on the understanding of their needs and challenges (Bartram, 2009; Tran et al., 2022). Moreover, most studies on support for IMDS are conducted within native English-speaking contexts (e.g., Bartram, 2009; Chai et al., 2020; Wang, 2023). Using a phenomenographic approach, this study explores how IMDS’ experience support at a Finnish university. The study aims to describe the qualitative variation in IMDS’ in ways of experiencing support, resources of support, types of support, and campus environmental factors that might affect student development in HE. This study contributes to the conceptualization of support for IMDS from a humanistic perspective.

International Students’ Support in Higher Education

Student support can be conceived as academic, pastoral, personal, social, emotional, or practical (Bartram, 2009). It mainly involves information, communication, assistance, help, provision of care, empathy, love, trust, guidance, and services (Bartram, 2009; Jacklin & le Riche, 2009; Roberts & Dunworth, 2012). The need for support varies across the stages of the study experience, HEIs, and countries, but it commonly includes assistance with visa immigration, travel logistics, information, orientation, integration activities with host communities, career, and internship guidance (Kelo et al., 2010; Yakaboski & Perozzi, 2018). Support provided especially in the initial stages is crucial to international students’ adjustment into the host country (Khanal & Gaulee, 2019; Rienties et al., 2014).

Many studies on international students’ support identify university staff, peers, and the international community as resources of support for their academic and social integration. Blanchard and Haccoun (2020) and Hallet (2010) found a significant positive link between academic staff support and students’ learning process; supervisors helped to develop students’ learning potential and become part of the academic community. Likewise, Filippou et al.’s (2017) study indicated that IMDS’ interpersonal relationship with supervisors shaped by frequent communication, emotional support, and guidance helped them during the thesis process, but culture-related study expectations were not visible. Additionally, Ling and Tran (2015) identified teachers and study coordinators as resources of support for academic issues, and peers from similar cultural backgrounds as a resource of socialization and comfort. Finally, Chai et al. (2020) found a significant positive relationship between international community support and international students’ academic success and social integration.

Another resource of support is university services. Huang and Turner (2018) found the support provided to develop international students’ employability skills was through different curriculum activities, but their engagement with career services was limited due to cultural differences in their perception of support from career services. Similarly, Nilsson and Ripmeester (2016) noted that IMDS in Europe were less satisfied with career services and expected more advice and guidance for the transition from studies to the labor market. Furthermore, Roberts and Dunworth (2012) concluded that IMDS believed in the usefulness of the support services in general, but often these services failed to address students’ needs, especially regarding cultural and career integration. International students’ experiences of support indicate support provided by university staff, the international community, and services are essential to their adjustment, learning process, social, cultural, and career integration into host communities.

In Finland, IMDS appreciate the study environment, informal social atmosphere, and communication with the academic community that often deviate from the more hierarchical atmosphere experienced in the country of origin (Korhonen, 2016; Niemelä, 2008). The Finnish education system is based on the principles of equal access, social, and educational democracy (Rinne, 2010; Välimaa, 2021), thus promoting students’ personal growth and developing autonomy and independent thinking (Finnish National Agency for Education, 2018). Moreover, the flexibility of the study degree structure allows international students to apply for several English-medium study programs, enroll in courses from different study programs and institutions, create personal study plans, and learn in a variety of learning modes (Moitus et al., 2020). Despite the appreciation for these principles, IMDS encounter academic, social, financial, and psychological challenges (Calikoglu, 2018). Some of the challenges that have persisted for over two decades include language barriers, lack of interaction with Finnish students and local people, lack of social networks, and lack of organizational support and guidance during different stages of studies (Kinnunen, 2003; Lairio et al., 2013; Niemelä, 2008). Improving areas of support for academic, social, cultural, and career integration during their study experience in HE and beyond is important not only for transitioning and integrating into host communities but also for increasing international degree students’ possibilities to find work and stay in Finland (Korhonen, 2016).

Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework of this study draws on two models derived from Student Development Theories (SDTs): Schlossberg et al.’s (1995) Transition Model, and Museus’s (2014) Culturally Engaging Campus Environment (CECE) Model. Schlossberg et al.'s (1995) Transition Model provides a framework for understanding factors that facilitate students’ transitions in HE. Schlossberg et al. (1995) define transition as “any event, or nonevent, that results in changed relationships, routines, assumptions, and roles” (p. 27), and “a transition is not so much a matter of change as of the individuals’ own perception of change” (p. 28). The Transition Model’s “4S System” of Situation, Self, Support, and Strategies, provides a way to identify the potential resources that student students have in their possession to cope with change. Several external factors or personal characteristics can influence how students cope with change in various situations, but support is the key to handling these transitions. Hence, Support is used in this study to identify IMDS’ types and resources of support that are used to cope with change. Types of Support are classified according to students’ resources, like intimate relationships, family units, networks of friends, and institutions and/or communities of which they are members. These resources are considered important during students’ transitions from secondary to tertiary education, from one country to another, or from studies to work. Regardless of where the student is in the transition process and what the transition is, each student responds differently depending on the available resources and types of support.

Museus’s (2014) CECE Model provides a framework to assess the elements of the campus environment that affect the experiences and outcomes of racially diverse student populations in HE. The model acknowledges that external influences (e.g., financial factors, employment, family influences); pre-university inputs (e.g., academic preparation and disposition); and racial and cultural realities in the campus environment shape students’ experiences and outcomes in HE (Museus, 2014). The model proposes nine indicators of cultural relevance and cultural responsiveness: (1) Cultural Familiarity, (2) Culturally Relevant Knowledge, (3) Cultural Community Service, (4) Opportunities for Meaningful Cross-Cultural Engagement, (5) Collectivist Cultural Orientations, (6) Culturally Validating Environments, (7) Humanized Educational Environments, (8) Proactive Philosophies, and (9) Availability of Holistic Support. CECE Model indicators characterize campuses that reflect cultural backgrounds, communities, and support systems responding to the needs of a diverse student population. CECE Model indicators are used in this study to identify aspects of the campus environment that resource support, thus affecting IMDS’ experiences and outcomes in HE (e.g., learning, development, satisfaction, persistence, degree completion).

We chose Schlossberg et al.’s (1995) Transition Model because it provides a framework to explore types and resources of support that might help IMDS cope with transitions. We incorporated the nine indicators of the CECE Model (Museus, 2014) to identify aspects of cultural relevance and cultural responsiveness in the campus environment that present potential resources for support at an HE institution. These models complement each other and together provide a comprehensive exploration of resources and types of support from individual and institutional perspectives. These models have been previously used in research on international students (e.g., Ballo et al., 2019; Belle et al., 2022; Montgomery, 2017; Wang, 2023), and are particular to the characteristics of an international student population, such as the IMDS in this study.

Methods

Phenomenography

Our study uses phenomenography to explore participants’ ways of experiencing support in HE. Phenomenography investigates, on a collective level, “the different ways in which people experience, conceptualize, perceive or understand various aspects of, and phenomena in, the world around them” (Marton, 1986, p. 31). The main characteristic is a non-dualist ontological perspective where the person and the world are considered inseparable, and where experience and thought are not distinguished (Marton, 1986). People experience the same phenomenon in a limited number of qualitatively different and interrelated ways, and participants’ experience is seen as a relation between the person and the phenomenon (Marton, 2000). The outcome of phenomenographic analysis is known as “outcome space,” which is a structured set of logically related categories describing qualitative variations in participants’ ways of experiencing or understanding a phenomenon (Marton, 2000, p. 105). Phenomenography is very useful because it captures the diversity of constructed realities, telling “what people think about their practice, which can then trigger them to change practice” (Kettunen & Tynjälä, 2018, p. 1). We chose phenomenography as a qualitative research methodology for this study to understand what IMDS have experienced and perceived as support in all stages (from pre-arrival to graduation) experience in HE, since phenomenography investigates a phenomenon on the collective level and the various ways of experiencing that phenomenon.

Participants

Participants’ diversity is important to capture the variation in ways of experiencing support and maximize the range of perspectives on the phenomenon (Bowden, 2005; Marton, 2000). We used purposeful sampling for the selection of informant-rich cases to reveal important group patterns (Patton, 2015). Because many studies tend to examine international students’ experiences alongside bachelor or doctoral degree students (Calikoglu, 2018), only master students were interviewed in this study to give greater attention to IMDS. In Finnish HE, IMDS typically study for 2 years (120 ECTS credits), yet fewer studies are done on this particular student population (Korhonen, 2016). For this, we interviewed 17 IMDS enrolled in 10 international master’s programs in different study stages at a Finnish university (2 on pre-arrival, 4 on arrival, 5 in their first year, 4 in pre-graduation, and 2 recently graduated). The participants (10 female, 7 male) represented 12 different nationalities from European (N=8), Asian (N=7), and African (N=2) countries. In qualitative phenomenographic studies, a small number of participants between 10 to 15 is sufficient to capture the variation (Kettunen & Tynjälä, 2018). Quantitative phenomenographic studies using a large number of participants (e.g., N=1622; Töytäri et al., 2016) did not provide any significant difference in terms of research outcomes compared to qualitative studies with at least 11 participants (Täks et al., 2014). Hence, 17 participants were deemed sufficient.

Data collection

The primary data collection method in phenomenography is interviews (Åkerlind, 2012; Marton, 1986). This study used semi-structured interviews focused on exploring how participants thought about support and eliciting underlying meanings (Åkerlind, 2012), which would then be jointly analyzed on a collective level. The open-ended questions were based on both the conceptual framework and the phenomenographic approach, allowing participants to discuss their understanding and experiences of support as openly as possible (Marton, 1986). For example:

· What does support mean to you? How do you understand support?

· Can you give an example of support provided to you before and after your arrival in Finland?

· What were the resources of support on pre-arrival, on arrival, and during your study and living experience in Finland?

Follow-up questions were asked to clarify what participants had said (Bowden, 2005), and make them reflect on their experiences of support. The participants were invited to an online interview through the coordinators of their respective study programs. Participation was voluntary, anonymous, and based on informed consent. The interviews were conducted in English by the first author, who was a former IMDS, in a relaxed atmosphere and in an environment chosen by participants, which facilitated the sharing of thoughts and experiences as students. Although no new information on experiencing or perceiving support emerged after the fourteenth interview, suggesting data saturation, we conducted additional interviews to ensure an adequate sample size (Täks et al., 2014). During the basic level transcription of the audio-recorded interviews, any identifiable personal or study-related information was anonymized. The interviews were conducted in May-August 2022 and lasted between 60 and 90 minutes.

Data analysis

In phenomenographic analysis, the significance of the research outcomes depends on the processes by which they have been obtained (Bowden, 2005). Practices of phenomenographic analysis vary from considering the whole transcript (Bowden, 2005), large chunks of each transcript (Prosser, 2000), or smaller excerpts extracted from the transcripts (Marton, 1986). Our analysis began with reading the transcripts as a whole and sought the meaning of the utterances in the context by moving backward and forward in the transcripts (Bowden, 2005). Some sections of the transcripts were considered more relevant to the research questions than others, but the whole transcript retains its significance during the analysis. All the transcripts were combined into one data set, considering the collective experiences of support, rather than individual ones, “despite the fact that the same phenomena may be perceived differently by different people and under different circumstances” (Åkerlind, 2012, p. 116). Phenomenography posits that no single transcript can be seen in isolation from the rest; transcripts are read as a whole, and neither the participants nor their characteristics are taken into consideration as independent entities in the data analysis (Täks et al., 2014). Readings were characterized by a high degree of openness with a focus on how support as a phenomenon appeared to the participants. Personal understandings or presuppositions about the phenomenon were “bracketed" to avoid personal judgments about the data and to ensure that the researchers’ previous knowledge did not influence the creation of the categories of description (Ashworth & Lucas, 2000, p. 296).

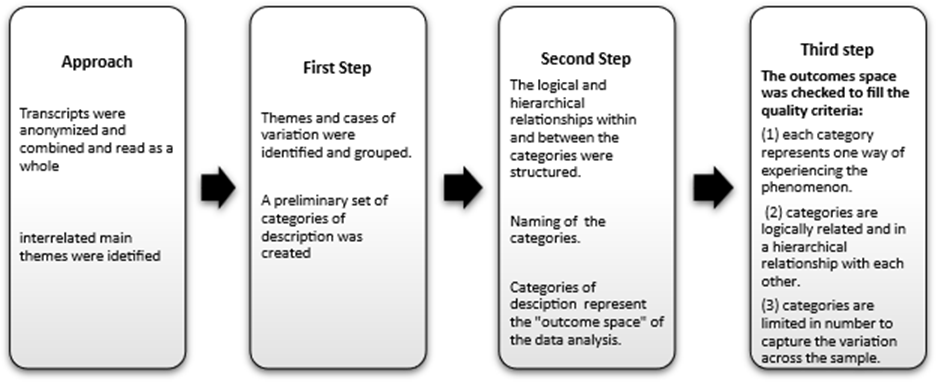

The three main steps of our analysis are presented in Figure 1. In the first step, by comparing and contrasting utterances, we identified themes of support experiences and cases of variation which constituted the data for the next steps of analysis. Subsequently, themes were sorted into preliminary categories (Marton, 1986). In the second step, we used the identified themes to delineate the logical and hierarchical relationships of the categories (Kettunen & Tynjälä, 2018), expanding from the least to the most complex way of experiencing support. These themes are called dimensions of variation or themes of expanded awareness since they reveal the aspects that differentiate the categories from each other (Marton, 2000). This process continued until no significant changes emerged and the stabilization of the categories of description was achieved. Then, excerpts were selected to illustrate each aspect of the categories. We named the categories later in this step to prevent them from fitting into pre-determined categories (Bowden, 2005).

A tabular approach was used to display the research outcome space of the analysis to unfold participants’ ways of experiencing support (Åkerlind, 2012). Phenomenographic research stresses the importance of team collaboration during the constitution of the outcome space (Bowden, 2005), and the first author conducted the first round of analysis and drafted the initial set of categories, and then all co-authors met several times to discuss, and revise the categories of description until their confirmation. In the third and final step, we checked the categories of description met the three quality criteria proposed by Marton and Booth (1997) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Steps Taken in Phenomenographic Data Analysis

Findings

This section elaborates on the four ways participants experienced support in higher education, namely (1) study system adjustment, (2) learning enhancement, (3) personal growth, and (4) autonomy development. Table 1 presents the various ways participants experienced support, capturing participants’ collective understanding of the phenomenon. The categories of description present how participants experienced support and aspects that differentiate each category are presented as dimensions of variation. Moving from top to bottom, the categories of description show how participants experienced support, and aspects that differentiate each category are presented as dimensions of variation. Moving from left to right, each dimension expands from the least to the most complex way of experiencing support showing the hierarchical relationship between the categories. The following subsections present the categories of description with selected excerpts illustrating the key aspects of each category and the relationship between the categories.

Table 1. Participants’ Ways of Experiencing Support at a Finnish University

|

Dimensions of variation |

Categories of description |

|||

|

Study system adjustment |

Learning enhancement |

Personal growth |

Autonomy development |

|

|

Relationships |

contacts (tutors) |

connections (teachers and supervisors) |

comfort (international coordinators) |

care (international community) |

|

Communication |

frequent |

facilitated |

open |

responsive |

|

Use of information |

getting instructions |

getting advice |

finding solutions |

making decisions |

|

Role of services |

informing |

counseling |

guiding |

integrating |

|

Study flexibility |

study options |

study opportunities |

study interests |

study pathways |

|

Learning environment |

space to obtain new knowledge |

space to expand knowledge |

space to grow |

space to develop |

|

Focus of the study system |

student participation |

student interaction |

student initiative |

student independence |

|

Study environment |

supportive |

sustainable |

safe |

free |

Categories of description

Category 1: In this category, support was experienced as study system adjustment. Participants experienced support being in close contact with tutors for their initial adjustment in pre-arrival and on-arrival stages in Finland. Frequent communication with tutors helped to develop close relationships and to become familiar with studying and living in Finland. Participants identified the role of services as informing, particularly getting instructions in English that supported their initial adjustment to the new study system (e.g., information about different adjustment courses). In this category, participants experienced the flexibility of the study system in many options they were offered to study in English. The learning environment was perceived as a space to obtain new knowledge supported by a study system that encourages students’ active participation in the classroom. Even though participants considered the adjustment phase as a challenging period demanding time, participants perceived the study environment as supportive of their adjustment, which counterbalanced the study workload.

My tutor was very helpful, he was excellent, he was sending me all sorts of information about living and studying, and I enjoyed all that frequent communication. We spent months chatting every day before and after my arrival in Finland. Thanks to that communication, I felt supported. (Communication)

I was very impressed with some courses that are there at the beginning to support students for their adjustment to the system. I was very happy with the kind of support that I got from university. (Use of information)

Finland has like a great variety of English-speaking programs. And my program in my opinion was one of the best programs that was provided, one of the best like variety of courses. (Study flexibility)

I really appreciate the study system. I think it’s much, much better than in my country, because I really liked the homework presentations, because it makes students really participate in the class. And it’s like learning by doing. (Focus of the study system)

So, I think in general, just like supportive environment that was very helpful, despite the fact that I had quite a lot of work, high level of workload, but I think this kind of supportive environment helped to work this out. (Study environment)

Category 2: In this category, support was experienced as learning enhancement. Participants perceived developing connections with university staff as supportive of their learning process. These connections were facilitated by an informal horizontal hierarchy that supported communication on different university levels, from administration to management and leadership. Participants used the information to get advice on different applications, course selections, and studies. The role of services was identified as an important resource for consultation on issues concerning their studies and to enhance their learning. Participants experienced the flexibility of the study system as the opportunity to study in different fields regardless of former educational background. The learning environment was perceived as a space to increase their knowledge in their study field. A study system focused on interaction with teachers and peers helped them to improve many skills and enhance their learning which was supported by a sustainable study environment.

They’re the persons you meet every single day. So, if you’re not connecting, they can’t help you, and you will never realize what you are missing in your learning process. (Relationships)

I can approach basically anyone in my department, and even talk with the management if I needed, and receive sufficient advice, and help if required. (Communication)

So, the university was flexible enough to accept me with a degree in psychology. Actually, the idea of the program that I got was that they would like to encourage students from different educational backgrounds to attend the Business School. [...]. And I think that was like one of the best points for the program that they stated that people of various qualifications have equal opportunities to study in the university. (Study flexibility)

So yeah, I think support was mainly in growing my knowledge or increasing my knowledge in education and educational policies. (Learning environment)

But in general, I can see that I learned a lot, I improved many skills, especially intercultural skills, because I told you, this is the first time I was studying in an international environment. (Learning environment)

I want to relate it with my study, in my study, there is a term called sustainability and this is a sustainable study environment. (Study environment)

Category 3: In this category, support was experienced as personal growth. Participants developed a comfortable relationship and open communication with the international coordinators of the study program which allowed free discussions about personal matters and shared opinions. This comfort relationship had value for the participants, representing a change in participants’ social relationships which is key to their personal growth. Participants used the information to find solutions themselves, particularly with time management to balance study and free time. The guidance role of services was perceived as supportive not only for academic matters but also for personal accomplishments. Participants used the information to find solutions themselves, particularly with time management to balance study and free time. The guidance role of services was perceived as supportive not only for academic matters but also for personal accomplishments. Participants used the information to find solutions themselves, particularly with time management to balance study and free time. The guidance role of services was perceived as supportive not only for academic matters but also for personal accomplishments. Participants experienced the flexibility of the study system, in teachers’ letting students choose topics for their course assignments that aligned with their study areas of interest. The capacity to acquire knowledge and broaden their areas of interest more than the courses’ topics represents a change in participants’ judgment of their capacity for their personal growth. Moreover, personal growth was further supported by learning that happened in a safe space and focused on the student initiative.

I was frequently contacting my international coordinator. Somehow, I feel connected with her, and she was my comfort lady. She was the person who was holding me up, encouraging me and the only person that I can talk freely… Somehow, she understands me. (Relationships)

Especially the international coordinators offered a lot of support. Yeah, they always said, if you need something you can freely ask. So, you will be not afraid to ask if it’s something you need. (Communication)

And it was helpful for me, because there was a lot of good information on the website, very good. [...]and using the info on the website, I found out some solution, yes. (Use of Information)

University services, because I believe that they were the ones guiding us with what to study and how to have the best experience in the university and like in Finland in general. (Role of services)

I was given guidance when it was necessary in the earlier stages. So, I think right now, it's just my own responsibility to accomplish my plans. (Role of services)

So, if you ask me about support, that was the room to grow for me as a person and as a student. (Learning environment)

I can understand the importance of safe space now because I have experienced it, I knew it only in theory, but now I really feel it as a student. (Study environment)

I think that the Finnish education system is very focused on [...] initiative of the student. (Focus of the study system)

Category 4: In this category, support is experienced as autonomy development. Participants experienced support when feeling cared for as a family member by the international community inside or outside the academic environment. This support stemmed from close relationships with a community formed by international peers, small study groups, and people with similar cultural backgrounds. Support was further experienced in international coordinators’ responsive communication to their needs and positive attitude towards students freely voicing their concerns. Participants used information from different sources to make their own decisions. The role of services was perceived as supportive of participant’s academic and social integration but also of their transition from studies to the labor market. Participants used information from different sources to make their own decisions. The role of services was perceived as supportive of participant’s academic and social integration but also of their transition from studies to the labor market. The flexibility of the study system is experienced in participants’ academic freedom and autonomy to build their own study pathways. The learning environment was perceived by participants as a space to develop their maturity in a free study environment inside and outside university settings which was connected to the study system that is focused on student independence and autonomy.

I told you that I used that information to decide on many courses offered from other departments [...] So, I’m happy that the university somehow respects my decision, I have this independence now. Yeah, that’s also very important for you as an international student. (Use of information)

And here in Finland, of course, there are some basic courses that are mandatory for everyone, but the level of academic freedom, I was really amazed for the first time in my life, I could create my own study plan, I could learn at my own pace, I could enroll or drop out courses as my preferences are. So, that amount of freedom and amount of offered courses that I’m not sure I even explored all of them. I was really amazed, I still am. (Study flexibility)

It’s not the personality that I used to carry since childhood. It is the maturity that I developed after coming here. So, university support in a sense, of course, has everything to do with this being that I developed. (Learning environment)

So yeah, I think everything was just excellent in terms of how free you are, to do different things and express yourself in ways that you are mostly comfortable with. I think, [...] in a way that you are free to be doing things, [...], I had a chance to do this because university was providing that free space for me and for other students. (Study environment)

Why Finland is where it is of that freedom that offers to students, you are responsible for your own education, you can follow your own interests, you’re not led by anyone. (Focus of the study system)

Relationship between the categories

To fulfill the second condition for quality in phenomenographic data analysis (see Åkerlind, 2012), the categories of description emerging from the data were differentiated from each other and arranged hierarchically in eight dimensions of variation (see Table 1). These dimensions of variation show how the IMDS’ experiencing support expands from one category of description to the next. This section presents this progression in complexity by highlighting the turning points or shifts whenever a change occurred in participants’ expressions or articulation, showing the direction or expansion of their understanding across each category of description.

Participants’ nature of relationships changed across the categories from interactions to feelings. Being in contact with tutors for exchanging information relevant to their study adjustment (Category 1) shifted in connections with teachers and supervisors for their learning enhancement (Category 2). A change was perceived and experienced in the nature of relationships, the feeling of a comfortable relationship with international coordinators (Category 3), and the feeling of being taken care of as family members within the international community (Category 4).

Other key dimensions were communication, the use of information, and the role of services. Communication diversified across the dimensions from frequent to responsive. Participants experienced frequent and facilitated communication with tutors and university staff as support for adjusting to the study system (Category 1) and enhancing their learning (Category 2). An increased complexity was noted when participants experienced communication as open to freely discuss issues and express opinions (Category 3), and as responsive to their needs (Category 4). Concerning the use of information, participants used it to get instructions to facilitate their study system adjustment (Category 1) and advice on the learning process (Category 2). A shift could be observed in participants’ more complex perception of using information to find solutions on their own to support their personal growth (Category 3) and to make their own decisions towards increasing their autonomy (Category 4). Moreover, participants experienced the role of services as informative (Category 1), especially concerning information in English for their study adjustment, and consultative in a way that participants felt it enhanced their learning (Category 2). A shift was discerned when participants experienced the role of services as guidance concerning study-related and personal matters (Category 3), and as integrating (category 4) as support for them to integrate in host communities.

Two key dimensions in which IMDS experienced support centered on the academic environments at their university. Participants’ perception of support within learning environments gradually transitioned from obtaining new knowledge (Category 1) and expanding their knowledge (Category 2) to a more complex understanding, where learning environments became spaces for personal growth (Category 3) and autonomous development (Category 4). Moreover, the study environment was experienced as supportive of adjustment (Category 1) and conducive to sustained learning (Category 2), but participants’ experiences became more meaningful, including a sense of safety (Category 3) and freedom (Category 4).

Such environments were connected to their learning at the university. Study flexibility varied across the categories from study options to study pathways. Participants perceived study flexibility as having several options to study through which to better adjust to the study system (Category 1), and equal opportunities to enhance their studies (Category 2). A more complex perception of study flexibility denoted a shift in participants’ perception of support as experiences that enabled acquiring more knowledge in areas of interest (Category 3) and building their own study pathways (Category 4). This may have been facilitated by the focus of the study system, which was understood as supportive towards classroom participation (Category 1) and interaction with peers (Category 2) but shifted into an understanding of it as supportive of student initiative (Category 3) and the independent development of studies (Category 4).

Discussion

This study phenomenographically explored how IMDS experience and perceive support at a Finnish university. The findings suggest this student population experiences support in four qualitatively distinct ways; perceived support as study system adjustment, learning enhancement, personal growth, and autonomy development. Moreover, the findings suggested that IMDS’ experiencing support was marked by variation along eight dimensions indicating resources of support. These dimensions were relationships, communication, use of information, the role of services, the learning environment, the study environment, study flexibility, and the focus of the study system. The study argues support for academic and personal transitions, resources of support, and a culturally engaging campus environment affect IMDS’ experiences and outcomes in HE.

One of the four ways participants perceived support was as a study adjustment. Earlier contacts with the host institution and tutors have been found to help IMDS in getting the necessary information at pre- and on-arrival stages but also making informed decisions (Khanal & Gaulee, 2019). For the participants in this study, this concerned choosing the right study program for them, selecting orientation courses, and creating their personal study plans. This is important because supporting IMDS in the adjustment stage has been found to predict their academic success and integration into host communities (Rienties et al., 2014). Moreover, it highlights the role of peer support in improving IMDS’ early adjustment to the new study system and academic environment (Ling & Tran, 2015). In that regard, highly relevant resources of support were information and communication in English, especially since IMDS lacked Finnish language skills. This highlights IMDS’ dependence on accessible and understandable information in the adjustment phase (see also Calikoglu, 2018; Korhonen, 2016).

The second way participants perceived support was as learning enhancement. This was particularly facilitated by a positive connection between IMDS and teaching and research staff at the university. Similar findings were reported by Blanchard and Haccoun (2020) and Filippou et al. (2017), where IMDS saw a significant expansion of knowledge and improvement in skills because of the supportive academic environment. Building a support system based on the relationships with the teachers, supervisors, and international coordinators of the programs was key to IMDS’ academic experience. However, both within and beyond this academic environment, the main source of support was the international community comprising peers and friends with similar cultural backgrounds. This has also been reported by Renties et al. (2014) and might explain why the domestic students and local community do not often engage with the international community in the Finnish context (Korhonen, 2016; Lairio et al., 2013; Niemelä 2008), suggesting the disconnection between the international and host communities persist. Positioning IMDS as an integral part of the host communities and creating a multicultural environment to engage domestic and international communities is academically, socially, and interculturally beneficial for both communities (Tran et al., 2022).

Support was additionally perceived as personal growth and autonomy development. This was strongly connected to participants’ perceived benefits of studying in Finland, particularly the overall flexibility, freedom, and equal opportunities in their studies. These elements are characteristic of Finnish higher education (Moitus et al., 2020; Rinne, 2010; Välimä, 2021), and may contrast with the more rigid study systems IMDS are traditionally associated with; if the latter constrains their freedom to decide over their studies, IMDS may experience the flexibility to decide about their study pathways and enhance their autonomy as supportive. The finding of support being perceived as personal growth highlights the humanistic perspective of support, which mediates academic learning and personal development (Bartram, 2009; Glass & Holton, 2021; McKeown et al., 2021). This stresses the importance of providing support to every student, including IMDS.

This study was conceptually founded on Schlossberg’s (1995) Transition Model and Museus’s (2014) CECE Model. Similar to Montgomery (2017), who used the same models, participants’ perception of support was connected to academic and personal transitions. The phenomenographic analysis suggested four qualitatively different ways in which IMDSs experienced and perceived support marked by variation along eight dimensions. In the light of Schlossberg’s Transition Model (Schlossberg et al., 1995), participants’ qualitative distinct ways of experiencing and perception of support indicate two types of support: support for academic transitions, seen in IMDS’ adjusting to the study system (Category 1) and learning enhancement (Category 2); and support for personal transitions, seen in IMDS’ personal growth (Category 3) and autonomy development (Category 4). The dimensions of variation and themes that emerged from the data analysis indicated the resources of support for these transitions (see Table 1) which resulted for example in changed relationships with communities in which they engage. According to Schlossberg (1995), transitions provide opportunities for individual growth and development but the environment where these transitions occur determines the degree of the impact at a particular time.

Considering the CECE Model indicators (Museus, 2014), two indicators could be identified in these dimensions. Relationships indicate the presence of Humanizing Educational Environments. This could be seen in tutors, teachers, supervisors, and international coordinators taking time to develop meaningful relationships through close contact, connections, and comfort, thus becoming trusted sources of guidance for the IMDS. The communication and use of information indicate the presence of Availability of Holistic Support, seen in participants’ opportunity to have access to faculty members at different academic, administrative, and leadership levels, primarily for information and communication.

Applying this model to qualitative data may help to draw tentative conclusions on the presence and the absence of certain indicators. In this study, for example, the other seven indicators that predict students’ academic success were absent (see Conceptual Framework). Thus, the campus environment may not have been culturally relevant to the needs of the diverse student population examined, despite participants’ overall positive experiences at the examined institution. Arguably, the presence of additional CECE Model indicators would keep them connected to their own culture but also increase their awareness of other cultures, sense of belonging, and identity sharing (Museus, 2014).

The findings of this study suggest that IMDS were academically supported to succeed in their studies, but this support was mainly experienced within university settings. Learning and study environments were supportive of participants’ academic integration, where participants experienced safety and freedom as students. However, beyond university settings, the absence of support for social, cultural, and career integration in the data suggested that participants may have encountered integration challenges similar to those reported in other studies on international students in Finland (e.g., Calikoglu, 2018; Korhonen, 2016). Participants of this study did not mention any source of support from governmental or municipal structures, which indicates a view of support only university-based. This view promotes an overreliance on communities and structures within the university and undermines the potential of non-university support systems. Institutional support has a strong influence on the decision to stay or leave the host country (Belle et al., 2022), and for this university-based and non-university support systems need to be explicitly involved to obtain a more complete picture of institutional support for IMDS.

Limitations and future research

Our study was theoretically informed by Schlossberg et al.’s (1995) Transition Model and Museus’s (2014) CECE Model, which have been used in studies on other student populations such as Chinese, African American (e.g., Montgomery, 2017; Museus, 2014), and mainly used with IMDS in English-speaking countries (Belle at al., 2022; Montgomery, 2017; Wang, 2023). We believe our study demonstrates that these models may also be applied to studies on international student populations in non-English speaking contexts. Moreover, the combined use of these models in this phenomenographic study provided a more comprehensive theoretical lens for the analysis and interpretation of the data. However, in exploring experiences and perceptions of support, other aspects of IMDS’ study experience, like feelings of isolation, challenges in interaction with the Finnish community, and language barriers, were shared but not sufficiently included in the analysis. Given the richness of interview data with IMDS, other methodological approaches, like reconstructive social research, may be able to capture and interpret such subjective experiences from a different perspective. The number of participants was considered acceptable for capturing variation in phenomenographic studies, and participants’ backgrounds reflected the diversity of the international student population in Finnish HE. However, the participants were interviewed at different stages of their study experience. Because each stage of the study experience may affect individual perceptions of support differently, future research may quantitatively explore the association between stages, length of stay in Finland, and experiences of support. The present research may help to inform quantitative studies assessing the actual impact of the provided support on IMDS’ academic success and integration into the host country.

This study contributes to the work of practitioners working with IMDS to support their integration into host communities. The findings suggested that more support should be offered for IMDS’ social integration by increasing the interaction with Finnish students and the local community. Designing courses, programs, and activities to study and meaningfully interact with Finnish students might increase the diversity of perspectives in the learning process and be beneficial to both domestic and international students. In addition, the findings could help practitioners in the field of student services to understand what IMDS experience as supportive in the adjustment phase and during their studies, but also what IMDS need in other stages, especially career planning and integration into the labor market. More tailored services and courses designed for partaking in the workforce in Finland should be offered (e.g., internships that support career integration during and after graduation). Additionally, activities designed to increase the interaction with Finnish students and the local community could facilitate IMDS’ to build networks for their career integration. Because the findings identified the role of services in counseling and guiding IMDS, we recommend practitioners use Schlossberg’s Transition Model as a practical guide to mentor or coach IMDS towards identifying their resources and support strategies to successfully cope with their transition experiences in HE. The CECE model is designed to ensure applicability across different types of campuses, and it is the responsibility of institutional leaders to deeply engage the cultural backgrounds and identities of diverse student populations to improve holistic development and student success outcomes in HE.

Conclusion

Our study contributes to the understanding of what IMDS experience and perceive as support in Finland, but also clarifies that the purpose of support offered to IMDS should aim not only for academic success but also personal development. The humanistic perspective of support, which has student personal development at its core (Bartram, 2009), is often not considered when designing support services for IMDS. We argue that before being international students, they are simply students and, as such, it is HEIs’ responsibility to not differentiate them when providing support to all students. Although this is a small-scale study, it is in line with earlier research in the Finnish context (Calikoglu, 2018; Korhonen, 2016; Niemelä, 2008). Over the last two decades, Finland has been increasing its interest in attracting more international students, largely for economic reasons (Jokila et al., 2019; Mathies & Karhunen, 2021). Hence, HEIs, governmental agencies, and local communities should provide support to IMDS because, while academic support will help them graduate, but social, cultural and career support may increase their integration into Finnish society and economy.

References

Anderson, M. L., Goodman, J., & Schlossberg, N. K. (2022). Counseling adults in transition: Linking Schlossberg's theory with practice in a diverse world (5th ed.). Springer Publishing Company.

Ashworth, P., & Lucas, U. (2000). Achieving empathy and engagement: A practical approach to the design, conduct and reporting of phenomenographic research. Studies in Higher Education, 25(3), 295-308. https://doi.org/10.1080/713696153

Ballo, A., Mathies, C., & Weimer, L. (2019). Applying Student Development Theories: Enhancing International Student Academic Success and Integration. Journal of Comparative & International Higher Education, 11(Winter), 18-24. https://doi.org/10.32674/jcihe.v11iWinter.1092

Bartram, B. (2009). Student support in higher education: Understandings, implications and challenges. Higher Education Quarterly, 63(3), 308-314. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2008.00420.x

Belle, T., Barclay, S., Bruick, T., & Bailey, P. (2022). Understanding post-graduation decision of Caribbean international students to remain in the United States. Journal of International Students, 12(4), 955-972. https://doi.org/10.32674/JIS.V12I4.3829

Blanchard, C., & Haccoun, R. R. (2020). Investigating the impact of advisor support on the perceptions of graduate students. Teaching in Higher Education, 25(8), 1010-1027. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2019.1632825

Bowden, J. (2005). Reflections on the phenomenographic team research process. In J. A. Bowden & P. Green (Eds.), Doing Developmental Phenomenography (pp. 63-73). RMIT University Press.

Calikoglu, A. (2018). International student experiences in non-native-English-speaking countries: Postgraduate motivations and realities from Finland. Research in Comparative and International Education, 13(3), 439-456. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745499918791362

Centre for International Mobility (2016). Suomessa, töissä, muualla? [In Finland, at work, elsewhere?]. Faktaa Express 1A/2016. http://www.cimo.fi/faktaa_express_1a_2016

Chai, D. S., Van, H. T. M., Wang, C. W., Lee, J., & Wang, J. (2020). What do international students need? The role of family and community supports for adjustment, engagement, and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of International Students, 10(3), 571-589. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v10i3.1235

Filippou, K., Kallo, J., & Mikkilä-Erdmann, M. (2017). Students’ views on thesis supervision in international master’s degree programmes in Finnish universities. Intercultural Education, 28(3), 334–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2017.1333713

Finnish Government (2021). Education Policy Report of the Finnish Government. https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/handle/10024/163273

Finnish National Agency for Education (2018). Finnish Education in Nutshell: Education in Finland. Ministry of Education and Culture, 1-28. https://www.oph.fi/en/statistics-and-publications/publications/finnish-education-nutshell

Glass, C., & Holton, M. (2021). Student development: Reflecting on sense of place and multi-locality in education abroad programmes. In A. C. Ogden, B. Streitwieser, & C. Van Mol (Eds.), Education Abroad: Bridging Scholarship and Practice (pp. 106-118). Routledge.

Hallett, F. (2010). The postgraduate student experience of study support: A phenomenographic analysis. Studies in Higher Education, 35(2), 225-238. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903134234

Huang, R., & Turner, R. (2018). International experience, universities support and graduate employability–perceptions of Chinese international students studying in UK universities. Journal of Education and Work, 31(2), 175-189. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2018.1436751

Jacklin, A., & le Riche, P. (2009). Reconceptualising student support: From “support” to “supportive.” Studies in Higher Education, 34(7), 735-749. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802666807

Jokila, S., J. Kallo., & M. Mikkilä-Erdmann. (2019). From crisis to opportunities: Justifying and persuading national policy for international student recruitment. European Journal of Higher Education, 9(4), 393-411.

Kelo, M., Rogers, T., & Rumbley, L. (2010). International student support in European higher education. International Review of Education, 58(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-012-9280-x

Kettunen, J., & Tynjälä, P. (2018). Applying phenomenography in guidance and counselling research. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 46, 1-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2017.1285006

Khanal, J., & Gaulee, U. (2019). Challenges of international students from pre-departure to post-study: A literature review. Journal of International Students, 9(2), 560-581. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v9i2.673

Kinnunen, T. (2003). If I Can Find a Good Job After Graduation, I May Stay. Ulkomaalaisten tutkinto-opiskelijoiden integroituminen Suomeen [Integration of international degree students to Finland]. Occasional Paper 2b/2003: Kansainvälisen henkilövaihdon keskus CIMO.

Korhonen, V. (2016). 'In-between' different cultures: The integration experiences and future career expectations of international degree students studying in Finland. In A. Harju, & A. Heikkinen (Eds.), Adult Education and the Planetary Condition (pp. 158-174). http://issuu.com/svvohjelma/docs/adult_educ_planetary_cond_2016e=15627691/36835887

Kuh, G. D., Kinzie, J., Schuh, J. H., Whitt, E. J., & Associates (2005). Student Success in College: Creating Conditions that Matter. Jossey-Bass.

Lairio, M., Puukari, S., & Taajamo, M. (2013). Kansainvälisten opiskelijoiden ohjaus korkea-Asteella [International students’ guidance in higher education]. In V. Korhonen, & S. Puukari (Eds.), Monikulttuurinen Ohjaus ja Neuvontatyö (pp. 258-278). PS-kustannus.

Ling, C., & Tran, L. T. (2015). Chinese international students in Australia: An insight into their help and information seeking manners. International Education Journal, 14(1), 42-56.

Marton, F. (1986). Phenomenography. A research approach investigating different understandings of reality. Journal of Thought, 21, 28-49.

Marton, F. (2000). The structure of awareness. In J. Bowden, & E. Walsh (Eds.), Phenomenography (pp. 102-116). RMIT University Press.

Marton, F., & Booth, S. (1997). Learning and Awareness. Routledge.

Mathies, C., & Karhunen, H. (2021). International Student Migration in Finland: The Role of Graduation on Staying. Journal of International Students, 11(4), 874–894. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v11i4.2427

McKeown, J. S., Celaya, L. M., & Ward, H. H. (2021). Academic development: The impact of education abroad on students as learners. In A. C. Ogden., B. Streitwieser., & C. Van Mol (Eds.), Education Abroad: Bridging Scholarship and Practice. Routledge.

Moitus, S., Weimer, L., & Välimaa, J. (2020). Flexible learning pathways in higher education: Finland’s country case study for the IIEP-UNESCO SDG4 project in 2018–2021. Kansallinen koulutuksen arviointikeskus. Julkaisut/Kansallinen koulutuksen arviointikeskus, 12:2020. https://jyx.jyu.fi/handle/123456789/72035

Montgomery, K. A. (2017). Supporting Chinese undergraduate students in transition at U.S. colleges and universities. Journal of International Students, 7(4), 963-989. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1029727

Museus, S. D. (2014). The culturally engaging campus environments (CECE) model: A new theory of college success among racially diverse student populations. In M. B. Paulsen (Ed.), Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research (pp. 189-227). Springer.

Niemelä, A. (2008). Kansainväliset tutkinto-opiskelijat Suomen yliopistoissa [International degree students in Finnish universities]. Opiskelijajärjestöjen Tutkimussäätiö OTUS.

Nilsson, P. A., & Ripmeester, N. (2016). International student expectations: Career opportunities and employability. Journal of International Students, 6(2), 614-631. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v6i2.373

OECD, (2019). Education at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/f8d7880d-en

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice (4th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

Prosser, M. (2000). Using phenomenographic research methodology in the context of research in teaching and learning. In J. A. Bowden & E. Walsh (Eds.), Phenomenography (pp. 36-46). RMIT University Press.

Rienties, B., Luchoomun, D., & Tempelaar, D. (2014). Academic and social integration of Master students: A cross-institutional comparison between Dutch and international students. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 51(2), 130-141. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2013.771973

Rinne, R. (2010). The Nordic University Model from a Comparative and Historical Perspective. In J. Kauko, R. Rinne, & H. Kynkäänniemi (Eds.), Restructuring the Truth of Schooling. Essays on Discursive Practices in the Sociology and Politics of Education: A Festschrift for Hannu Simola (pp. 85-112). Jyväskylä University Press.

Roberts, P., & Dunworth, K. (2012). Staff and student perceptions of support services for international students in higher education: A case study. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 34(5), 517-528. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2012.716000

Schlossberg, N. K., Waters, E. B., & Goodman, J. (1995). Counseling Adults in Transition (2nd ed.). Springer.

Täks, M., Tynjälä, P., Toding, M., Kukemelk, H., & Venesaar, U. (2014). Engineering students’ experiences in studying entrepreneurship. Journal of Engineering Education, 103(4), 573-598. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20056

Tran, L., Blackmore, J., Forbes-Mewett, H., Nguyen, D., Hartridge, D., & Aldana, R. (2022). Critical Considerations for Optimizing the Support for International Student Engagement. Journal of International Students, 12(3), i-vi. Retrieved from https://www.ojed.org/index.php/jis/article/view/5117

Töytäri, A., Piirainen, A., Tynjälä, P., Vanhanen-Nuutinen, L., Mäki, K., & Ilves, V. (2016). Higher education teachers’ descriptions of their own learning: A large-scale study of Finnish Universities of Applied Sciences. Higher Education Research and Development, 35(6), 1284-1297. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1152574

Välimaa, J. (2021). Trust in Finnish Education: A Historical Perspective. European Education, 53(3-4), 168-180. https://doi.org/10.1080/10564934.2022.2080563

Wang, L. (2023). Starting university during the pandemic: First-year international students’ complex transitions under online and hybrid-learning conditions. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1111332

Yakaboski, T., & Perozzi, B. (2018). Internationalizing U.S. Student Affairs Practice: An Intercultural and Inclusive Framework. Routledge.

Åkerlind, G. S. (2012). Variation and commonality in phenomenographic research methods. Higher Education Research and Development, 31(1), 115-127. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2011.642845