Vol 8, No 3 (2024)

https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.5713

Article

Exploring Child Standpoint Theory in Early Childhood Education: A Pathway for Cross-Cultural Comparisons

Annica Källebo

Stockholm University

Email: annica.kallebo@edu.su.se

Abstract

This empirical study in Bangladesh explores the potential of Child Standpoint Theory in constructing and reconstructing the child in early childhood education (ECE) and its role in facilitating cross-cultural comparisons in and of ECE systems. The comparative gaze is considered for ways of scholarly investigation in the context of ECE system messiness. The paper suggests viewing children as relational ethnographic units of comparisons for comparing the conditionality, contextual elements, and temporality of each child's education across cultures through a three-fold approach. Spanning method and theory, the approach combines the notion of the entangled researcher and the comparative case study tool of tracing with Child standpoint theory. Findings are presented through a comprehensive visualization of a ‘child’ going through the ECE system during a day as a pathway to deeper analysis of facets underpinning ECE from a bottom-up rather than top-down approach.

Keywords: Early childhood education, Comparison, System messiness, Child standpoint theory, Bangladesh

Introduction

Comparing the pedagogy that shapes early childhood education (ECE) practices in different systems is not easy, and ECE is often viewed as a supplementary 'add-on' or is disregarded when comparing education systems worldwide. With regards to pedagogy alone, differences abound in terms of theories, principles, integration of play, and specific pedagogic practices on different groups (i.e. gender, special needs). The alignment of ECE with primary education is also poorly researched. Yet, research suggests most contend that ECE is the most important consideration when educating the child as well as when comparing all levels of schooling. With this placement of ECE in the greater context of educational research, the perception has been that it is not a stand-alone system, with scholars highlighting it as a sector (Tobin, 2022). Furthermore, while there is recognition of the wide birth of pedagogical practices across cultures (Urban, 2022), there is a vast neglect of its messiness (Guevara, 2022). Scanning of the so-called sector of ECE justifies the means to consider researching such a rich educational area of study but to do so in a systematic way to draw from and develop units of comparison. This research aims to give credence to the importance of ECE and to explore how to compare messy systems on a global scale.

A recent global ECE policy document (UNESCO, 2022), recognized that research concerning the child in education, and the educational systems surrounding them, is for the most part divisive. The Tashkent Framework (UNESCO, 2022) persuasively argues not to lose oversight of the child in education—a relevant reminder for identifying what is considered as the core and that it is the child that should be considered forefront with curricula, pedagogy, and practice as secondary to meeting the needs of the child. Parenthetically and upon deeper investigation, there are extraneous, conditional aspects of the child that require further investigation when approaching the intrinsic benefits of ECE, as these aspects have direct and indirect impacts on the education of the child and the child's educational attainment. This research argues that the child as core is necessary as a unit of comparison before any research can be undertaken to explore different ECE policies, pedagogical approaches, or practices. By placing greater emphasis on the child, which includes every facet of the conditions underpinning ECE education regardless of level or age, one can re-construct contextual and temporal elements that allow for more robust units of comparison across cultures, SES divides, and ECE educational programming and interventions.

Ethnographic research was undertaken in Dhaka, Bangladesh in 2023 to explore and document aspects of the child within different ECE settings, to approach the question of how and if units of comparison could be drawn from very different education systems. By positioning the child as the main actor in this ethnographic case study analysis, the child could be treated as both subject and object, which helps to position actions for and within education (viewed as the verb whether passive or active as in a sentence). My role as researcher and practitioner posits the gaze of applying theory to practice, but also as an active participant in the research, defining, recasting, and re-constructing for comparative purposes.

This article employs the Child Standpoint Theory (Medina, Minton, 2019) to research the child as the central core of ECE. Through tracing (Barlett & Vavrus, 2017) and, in combination with the positionality of the entangled and detangling researcher (Sobe & Kowalczyk, 2018) this ethnographic case study analysis aims to construct and re-construct the child (regardless of systems) to map and piece together ECE messiness (Guevara, 2022) from the perspective of the child. The empirical data gathered through observations and entanglement, builds on interactions with the context of Bangladesh started in 2019. It will be qualitatively analyzed to showcase a child's 'lifeworld' of the day-to-day conditionality of its ECE educational pursuits. For anonymity purposes, a composite character representing a Bangladeshi child (referred to as Kadali) is developed to explore the following research questions:

1. Does Child Standpoint Theory (CST) offer direction in constructing and re-constructing the child in ECE?

2. If the child could be viewed as a relational ethnographic unit of comparison, how might this research aid the development of ECE comparisons across nation-states and cultures?

Positionality of the comparative gaze: approaching ECE systems and the child

The comparative gaze (Kim, 2014) is used as a source of comparative knowledge creation for this article. For comparative knowledge creation, Kim (2014) draws on mobility as academics move between contexts, cases, and concepts in which iterative comparisons continuously occur. In this paper, the academic movement between Sweden and Bangladesh serves as the context that enabled the creation of comparative knowledge, a process that began in 2019. The positionality of the comparative gaze is important to acknowledge between ECE contexts as both observer and participant, as each context struggles with its own type of complexity and system messiness and the perceived role I play in the research.

ECE system messiness a concept contributed by Jenifer Guevara (2022, p. 340) is used to describe and capture actual conditions of ECE systems on a subnational level. Rather than a national level, the sub-national level is understood to be where policy intentions and enactments, issues of governance, curricula, and access to education interact. The concept of system messiness suggests that national research approaches act as a veil that conceals subnational disparities in ECE systems. To approach this, Guevara (2022) suggests a shift, moving from top-down to bottom-up research approaches. This is a shift well needed, as national (systemic and policy) research approaches are argued to only harbor the ability to study and portray smoothed-out versions of subnational messiness. This results in research conceptualizing obscured versions of ECE systems. As suggested by Guevara (2022), the national level consists of several subnational messinesses that, consequently, require approaches that consider multiple adjacent (regional) contexts as sediments layered across and on top of each other that, when put together, make up a national ECE system, or sector. The comparative gaze between contexts observing this messiness amounted to the underlying understanding of ECE systems as complex phenomena.

Furthermore, Sweden and Bangladesh emerge as vastly different, perhaps, an example of most different systems (Anckar, 2008), as there are fundamental differences across multiple dimensions (e.g., histo-socioeconomic). Differences also prevail in ECE (beyond the overt differences between unitary and split-phase ECE systems (e.g., Bertham & Pascal, 2016; Eurydice, 2019) as observed while moving horizontally (practice-oriented) and vertically (policy-oriented) across the systems as an ECE teacher and teacher trainer in Sweden and a pedagogical developer and an ECE lecturer in Bangladesh.

While the labelling of positions may appear similar, they connote two defining characteristics. First, is the author’s prior knowledge in the ECE space as a practitioner, and second as a researcher who may be perceived as both an expert and/or biased in conforming to conventional views. In Bangladesh’s messiness, there are inequalities in ECE provisions, paradigmatic policy developments, e.g. The Child Daycare Act (see Rahman & Kamra, 2024), rapidly increasing enrolment rates, and rampant teacher shortages. In Sweden, a schoolification with ECE organizational structures that tends to mimic those of compulsory schools, and an apparent rush to match intended educational quality while, at the same time, experiencing decreases in public funding. To gain a nuanced understanding of similarities and differences in and between systems, it would be logical to approach the gap between policy and practice (Vandenbroeck, 2020) to understand realities, consequences, and contradictions in practice. However, as understood by policy studies in education, policy intentions do not always match policy outcomes in practice.

The comparative gaze is not only an effective tool for understanding the messiness of ECE systems but also serves as a lens through which to view the role of the child within these systems. By considering children as navigators (both as subject and object) in the messiness, we can shift our perspective and gain unique insights for comparative purposes. This approach prompts asking what theoretical and methodological tools are needed for cross-cultural investigations and how we can identify what remains constant within diverse systems. By investigating children as subjects and objects themselves using the Child Standpoint Theory (Medina-Minton, 2019), one can explore and compare the conditionality of each respective child, the contextual elements that enable or detract from the education of the child, the temporality of each situation, and to draw comparative inferences across cultures as units of measurement.

Through the comparative gaze, previous studies centering around children as core have sought to seek the limitations and pitfalls of such endeavours. One such example is Kousholt’s study on children’s transitions between home and daycare in Denmark (Kousholt, 2019). In the study, using the concept of conduct of everyday life as the “personal task of making life hang together across varied activities and contexts is a conflictual process that is deeply embedded in social coordination and influences social self-understanding” (Kousholt, 2019, p. 149). Kousholt posits the need:

…to conceptualize children’s development as anchored in an everyday life across different contexts and different social practices. Furthermore, this situation must influence approaches to care and developmental support, since taking care of children involves gathering information about and relating to the child’s everyday life in other contexts and cooperating with other adults to support the child’s well-being and development. (Kousholt, 2019, p. 145)

Further, material drawn from ethnographically inspired participant observations across children’s different lifeworld contexts and from interviews with children and their parents is represented through vignettes of the everyday conduct of children and their families.

Seemingly, with a gaze upon children as core in ECE, the theoretical concept of conduct of everyday life would enable a researcher to accompany children through the course of a day by mapping out each ECE service children attend which allows for conclusions to be drawn about learning opportunities. However, there are limitations and pitfalls when approaching it with the intention of comparability that maintains oversight of the child and system. The ethnographic smallness of mapping out one child’s ECE attendance might cause a loss of oversight of the system in which the attended practices were enclosed. Additionally, the messiness of systems would perhaps require a researcher well familiar with local ECE practices, as well as a relationship with the child in question that would allow for this kind of insistent ethnographic closeness. Put together, it could make cross-cultural ECE studies difficult to combine in a way that does not obstruct the visibility of the system as a whole.

Through the comparative gaze tracing between ECE systems, one can, as this study suggests, consider the specific subjectiveness of children, using the Child Standpoint Theory (Medina-Minton, 2019). Although the theory still is unfolding, there is great potential offered for drawing upon the epistemic advantage in placing children as core to understanding every facet of the conditions underpinning education, and for viewing them as a relational ethnographic unit of comparison. Approaching this task through an ethnographic lens serves an important purpose as system messiness poses a difficult-to-navigate reality of ECE systems. In which, gaps, dynamics, and conditions have been rendered invisible by policy and other dominant narratives as they only conceptualize obscured versions of these realities. Parents and guardians may be the ones to initiate children’s participation in education in a way that accommodates family dynamics and needs, however, the child’s participation itself is developed, shaped, and conditioned by the system that forms practices in which they are enrolled. Consequently, the child has little agency in the “personal task of making life hang together” (Kousholt, 2019, p. 149) as other actors and structures prescribe how ‘life hangs together’ for the child.

Background on ECE in Bangladesh

The empirical study was conducted in Dhaka, Bangladesh and a brief background of the ECE context is introduced before moving into the next sections.

The early non-formal education setting for children under the age of eight, the Qawmi Madrasa, stems from pre-independence (Khondoker, 2019). Following the 1971 Liberation War, most governmental efforts in education were focused on building mass and popular education and expanding primary and secondary schools. The earliest (semi) formalized education for the youngest children began in the 1980s, when the then newly established primary schools assigned small sections of space to sporadic Baby Classes to be held inside their facilities (Sikder, 2018). Being the first semi-formal ECE setting, the Baby Classes became an essential case for Bangladeshi ECE advocacy throughout the 80s. During the later parts of the 1980s, research institutions, NGOs, and advocacy initiatives, e.g., the Bangladesh Shishu Academy, focused campaigns on bringing ECE to the attention of the broader society to formalize ECE settings. However, the development of curricula for the Baby-Classes was left without action from the government. In the early 1990s, NGOs led the efforts to bring about the Integrated Non-Formal-Education Programme, in which preschool-like activities such as pre-writing and numeracy skills were promoted and employed by organizations such as Save The Children, BRAC (Building Resources Across Communities), and Bangladesh Early Childhood Development Network (BEN).

In light of the Bangladeshi Education for All efforts in the 1990s, ECE was again left outside the governmental efforts to ensure education for all, similar to many other nations at this time. It was not until 2008 that the first national policy, The Operational Framework (MoPME, 2008) on ECE, was formalized (Akhter & Chaudhuri, 2013). To launch this policy, major collaborative efforts by the Ministry of Primary and Mass Education (MoPME), Ministry of Women and Children (MoWCA), Dhaka University, Dhaka Ahsania Mission (DAM), and UNICEF (Sikder, 2018) took place and marked a significant step in the national mainstreaming process of ECE. The launch of The Operational Framework was followed by more rapid policy advancements through the National Education Policy (2010), Early Learning and Development Standards, ELDS (2013), and Comprehensive Early Childhood Care and Development (MoWCa, 2009).

Today, the provision of ECE services from private providers is prevalent worldwide, and a widespread phenomenon in Bangladesh. Private providers have been a growing trend (UNESCO, 2021), and since 2014, the majority of children have been attending these settings (World Bank, 2020). The broad trend can be further understood in relation to two recent policy developments that significantly impacted the ECE landscape. These are the Bangladeshi Labor Act (2006) (IFC, 2019) and the Child Daycare Center Act of 2021. The Labor Act instated that ECE was to be regarded as an employment benefit, where companies, factories, and offices employing over 40 women should provide employees with an ECE service. This was to be provided (similar to how the early Baby-Classes were provided within the primary schools) inside the companies’ facilities. As demand for ECE services- and professionals skyrocketed in the major cities of Dhaka, Khula, and Chittagong, private ECE providers began to expand rapidly (World Bank, 2020), offering tailored solutions to companies. Companies abiding by the Labor Act were obliged to provide the facilities and salaries for the ECE teachers. The teachers and the curriculum are delivered by a third-party ECE provider to the company through a bidding process. In light of these developments, mainly in major cities such as Dhaka, the parliament acted with support from the World Bank to pass the Child Daycare Center Act bill (2021). Being the first comprehensive regulatory policy for the whole ECE sector, it aimed, on the one hand, to accelerate re-enrollment, enrollment, and expansion of public ECE provision but also to regulate the private ECE sector, which had been left unregulated. Regulatory limits were set regarding enrollment and monthly fees, instating the obligation to register ECE services, penalties for misconduct in management, and fines for neglect or mis-care of children.

Today, out of the approximately seventeen million children under the age of 5 years in Bangladesh, approx. 3,6 million were enrolled in an ECE service in 2018 (World Bank, 2020). Statistics are notoriously difficult to attain in Bangladesh regarding children since it was not obligatory nor entirely possible to register newborn children until 2022. Most of the 3,6 million children are enrolled in private or NGO-funded ECE centers (48,1%) or governmental pre-primary classes (47%). The rest are enrolled in experimental-, community- or religious ECE settings. However, an important distinction is the difference between ECE and pre-primary (PPE) classes, as enrollment in the latter has been promoted under Bangladeshi efforts to offer one year of school preparation before primary school enrollment to 5-year-olds.

Theory

This paper assumes system messiness to be complex and thus a factor for consideration in scholarly investigation and comparison. Consequently, suggesting a three-fold approach that combines three aspects spanning method and theory. Initially, the relationship between researcher and context afforded by Sobe and Kowalczyk’s (2018) notion of the entangled researcher, secondly, the function for outlining a case study provided by Barlett and Vavrus’s (2017) tool of tracing, which, through Child Standpoint Theory (Medina-Minton, 2018) becomes theoretically informed. To discuss the role of Sobe and Kowalczyk (2018) and Barlett and Vavrus (2017), the Child Standpoint Theory (Medina-Minton, 2018) will first be introduced.

Departing from the basic claims of standpoint theories, e.g., as Friesen and Goldstein (2022) describe:

a standpoint is arrived at as a result of two necessary components, a marginalized social location and a process of critical reflection, and once arrived at, a standpoint offers an epistemic advantage over other positions with regard to relevant scientific pursuits. (p. 661)

However, traditional standpoint theories mainly consider adult subjects, and returning to the comparative gaze, recognizing the need for theories that take into consideration the particularities of children as subjects, requires adaptations. Therefore, considering the more recent developments in standpoint theories, the Child Standpoint Theory (Minton-Medina, 2019) is more suited for the study. While bringing it forward, Medina-Minton (2019) builds on a history of childhood and argues that children are an oppressed group, therefore the child’s position is a marginalized social location. A location that, similar to what other standpoint theories claim, affords epistemic advantage when included in scientific pursuits.

Currently, the Child Standpoint Theory is still developing and unfolding its potential, applicability, and utility. Few studies have explored it so far. McFadden et al.’s (2023) ethnographic study on child-led tours in daycare “(…) coupled with an adult researcher’s commitment to anti-oppressive practice through methodological accountability“ (…) “in mitigating asymmetrical power relations” (…) for meaningful (active) participation for children” (McFadden et al., 2023, p. 1-7). In their study, Child Standpoint Theory is used for preventing “tokenistic methodology” (McFadden et al., 2023, p. 12) but is also used through the analytic process and researcher reflective practice. However, further exploration of the theory and its limitations is needed.

As the purpose of the current study is to center children as the core of ECE certain power relations found in the relationship between child and researcher need to be addressed in regards to its role in comparative research. Specifically, as brought by the one-to-one dynamic of one individual child leading one individual adult researcher on the above-mentioned tours, prompted questions about whether it actually mitigates asymmetrical power relations in the meeting between actors. Most noteworthy, regarding the analysis process, “an adult-led analysis on a child-led tour may bias the interpretation of the tour and the findings, rendering a child standpoint praxis moot” (McFadden et al., 2023, p. 13). Furthermore, as previously noted in the study by Kousholt (2019), there is a limitation to the smallness and closeness of this ethnographic experience which can prevent comparability on a larger scale. As previously noted in the relationship between child and adult in the study of Kousholt (2019) Child standpoint theory (Medina-Minton, 2019) so far, struggles with its applicability in small-scale ethnographic studies. However, as Medina-Minton (2019) argues, a standpoint theory not only aims to scrutinize power relations on a small scale but also “aims to inform social science practice, positively change society, and provide another view than that of the dominant power” (Medina-Minton, 2019, p. 440).

Therefore, adopting the Child Standpoint Theory (Medina-Minton, 2019) in the current study, also implies emphasizing the epistemic advantage of considering children as the core for understanding facets of the conditions underpinning ECE education. With this understanding, the broad consideration of children’s standpoints and views is approached through a further nuanced understanding of children’s perspectives. Children’s perspectives are a multifaceted scholarly arena ranging from simply letting children speak on issues relevant to their lifeworlds to allowing researchers to intake perspectives of children, or a child perspective for guiding scholarly investigation. Therefore, the notion of children’s perspectives stretches across a spectrum of approaches, thus incorporating a child’s perspective, perspectives of the child, or a child's perspective involving vastly different methodological approaches. A child’s perspective (e.g., Qvarsell, 2001) could involve individual children as research participants in which the perspective and voice of the child itself is the source of knowledge, similar to the above-mentioned study by McFadden et al. (2023). The perspective of the child (e.g., Perselli & Haglund, 2022) could involve multiple children as the sources of knowledge, forming a collective voice and perspective of children as a group. Both perspectives position children as active subjects and agents in knowledge creation. However, the current paper stretches further to involve a child perspective, that stems from notions from The Convention on the Rights of the Child (see e.g., Aronsson, 2012; Bergnehr, 2019).

A child's perspective differs from the other perspectives, those of a child’s perspective and perspectives of the child, as there is more emphasis on the adult interpretation of how an individual child, or group of children as a collective, from their position, would interpret issues relevant to their lifeworld. However, a critical aspect needs to be addressed. As traditional standpoint theories connote “critical reflection” as described by Friesen and Goldstein (2022, p. 661) this comes into another light with the Child Standpoint Theory (Medina-Minton, 2019) as it poses the different ways adults are involved in representing the positions, locations, and perspectives of children, as highlighted as a limitation in the study of McFadden (2023). To mitigate this fragility, this paper involves a child perspective that traces the physical location of the child as the “phenomena of interest” (Barlett & Vavrus, 2017, p. 6). Doing so, positions the child as further passive, as a non-participant in the current study, and in which the role of the adult is to exercise the responsibility of mindful (rather than authentic; see James, 2007, p. 265) representation of the position, intention, meaning, and implication of the perspective of the child in issues relevant to the lifeworlds of children. Thus, there is an additional layer of responsibility for interpreting and representing the outside world on the adult’s behalf. This layer poses other types of questions about how a child's perspective could be mindfully transformed, incorporated, or included, on a practical level, within the spheres that have possibilities of actualizing changes within children’s lifeworlds. Therefore, when considering the relationship between researcher and context it is important to argue for a mindful representation of children's lifeworlds while positioning them as the core for understanding facets of the conditions underpinning ECE education as afforded by the nuanced understanding of the Child Standpoint Theory (Medina-Minton, 2019).

Methodology

Considering that an ethnographic study depicting an individual child’s educational trajectory (as pointed out in the case of Kousholt (2019) relies on the ethnographic closeness i.e., the relationship between the child-researcher, to produce insights of a particular ethnographic smallness (case). Instead, in this study, the relationship between researcher and context is understood as further important for shifting the emphasis of the relationships from researcher-child to that between researcher-context (in which where the child is located). Sobe and Kowalczyk (2018) connote this relationship and employ the notion of the researcher as entangled with context and, the one who detangles the context. In their suggested approach, context is understood as:

a process of interweaving, where the social embeddedness of education is understood as interwoven through the relationality of objects, actors, and environments, with the researcher playing an important "entangling" role in the construction of educational research contexts (Sobe & Kowalczyk, 2018, p. 197).

Similarly, suggesting that this relationship demands a constant adjustment in tracing the “messy ways in which people, objects, and ideas intercross (…) inclusive of the researcher’s perspective (s) and intervention(s)” (Sobe & Kowalczyk, 2018, p. 202). The relationship therefore demands movement on behalf of the researcher in the pursuit of tracing movements in context that depend upon the observed phenomena. These ambiguous and unpredictable movements connect Barlett and Vavrus’s (2017) argument of rejecting a priori bounding of a case, in their comparative case study approach (CCS) with Sobe and Kowalczyk's (2018) understanding of the relationship between context and researcher. Rather than apriori bounding of a case, Barlett and Vavrus (2017) suggest tracing relevant actors as a tool for outlining the boundaries of a case. When outlining a case, it implies tracing observed phenomena horizontally, vertically, and transversally, requiring similar movements of the researcher as suggested by Sobe and Kowalczyk (2018). In light of system messiness (Guevara, 2022), tracing therefore becomes a way to outline, from the position of the child, the boundaries of the system, from the vantage point relevant to children when enrolled in education. Tracing the position of the child inside the system could provide insight into aspects of the messiness that permeates the local context.

The Ethnographic Case Study Analysis

Ethnographic fieldwork in Dhaka was conducted in Jan-Feb 2023, where prolonged observations at daycares, preschools, and ECE centers were accompanied by interviews with teachers. Sampling was enabled through the network in Dhaka established since 2019.

Table 1. Overview data collections

|

District: |

Dhanmondi |

Tejgaon |

Jahangir |

Mirpur 11 |

|

ECE service offers: |

Play-group, Nursery, Kindergarten |

Daycare |

Daycare |

Tutoring |

|

Serves nr of children |

45 |

15 |

55 |

Per class 20 |

|

ECE type |

NGO for-profit owned |

Corp. funded-Private for-profit owned |

Private for-profit owned |

International for-profit owned corp. |

|

Teachers interviewed: |

6 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

Through observations in daycares, learning about children's in-setting routines of song-gatherings, rhymes, and emerging friendships, in preschools, of tidy desks, turn-taking, sequencing of lessons and play-brakes, and in tutoring classes, of route-learning, heavy homework, and large backpacks, a series of questions arose as the relationship between researcher and contexts grew more entangled (Sobe & Kowalczyk, 2018). All settings shared a troubled rhythm connected through a fragile fabric. Strict timelines and schedules of practices for keeping dedicated time slots before children were rushed to other ECE settings. From daycare to preschool, to tutoring, and back to daycare again. Following the movements by tracing “the phenomena of interest” (Barlett & Vavrus, 2017, p. 6) at a later stage, rushing through traffic with adults (gatekeepers) bustling between pick-up and drop-offs, the observations continued. How is educational attainment conditioned by it, and what relationships can form when children constantly move between ECE settings which, seemingly are structured around premises other than those benefitting the child?

These observations, enabled through the researcher's entanglement shaped the interviews with preschool teachers. Initially focused on pedagogical practices interviews evolved to encompass questions on the structural information of the centers, the history of their establishment, and the strategies employed for children's enrollments. The in-situ observations served as catalysts for further questioning during interviews, on the teachers' daily routines, which naturally shifted towards the daily routines of the children. Preschool teachers shared about the delicate balance between their roles as educators and parents, highlighting the important role of grandparents in sustaining family routines, particularly in facilitating their own children's attendance at multiple ECE settings.

In-situ familiarization of the interview data prompted deeper exploration into the everyday routines of children within and between ECE settings. Engaging with the teachers and key gatekeepers, accompany them during the pickups of their own children. These firsthand experiences provided valuable insights into the complexities that arise when children navigate multiple ECE settings and the ripple effects on family dynamics. Data collected from daycare centers, preschools, and tutoring facilities provided rich narratives of teachers' experiences in accommodating children attending multiple ECE settings. They recounted the pragmatic and pedagogical adjustments required to accommodate children's late arrivals, often necessitated by shifting routines in the settings they arrived from. For ex-situ analysis of interviews, qualitative content analysis (Bryman, 2016) was conducted to systematically identify and extract all sayings where interviewees mentioned information on structural characteristics, processual aspects, routines, schedules, and opening hours to visualize the multiple adjacent ECE settings children attend during a day. Further, the observations afforded by the entangled researcher on the physical position of children in between ECE settings function to place the child within the structural frame derived through interview data.

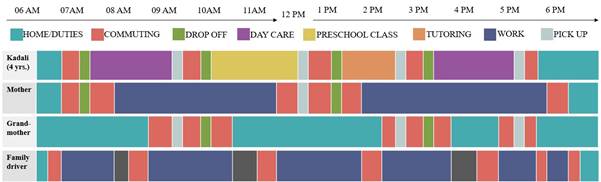

These various characteristics identified in the interviews have been visually represented and color-coded (see Table 2). The composite case allows us to present a comprehensive visualization of several children’s days going through the ECE system in Dhaka in combination with ethnographic and contextual data. Hence, as highlighted, to mindfully transform, incorporate, and include the knowledge production afforded by tracing (Barlett & Vavrus, 2017) children’s physical positions for allowing the knowledge production on a practical level to be mindfully represented to the outside world, within the spheres that have possibilities of actualizing changes within children’s lifeworlds. Some children enrolled in the daycare that is displayed (purple) also attended the displayed preschool (yellow) and, the tutoring (orange). While other children enrolled in the same displayed daycare commuted to other types of preschool settings and tutoring services. This study focuses on one such educational path. Although observations in the field account for multiple different examples, this study accounts for three of the settings, functioning as exemplary cases of the multiple settings children belonging to the Bangladeshi middle-class, attend during the course of one day. The choice of representing multiple children through a composite case presents the children as a collective, which is a way to pinpoint the initial argument made in the paper. This allows for the researcher to not lose oversight of the child enrolled in education, while simultaneously not losing oversight of the systemic dimensions.

Findings

Initially, structural information of ECE in Dhaka is provided before the comprehensive overview of the composite case of Kadali is introduced. Daycares in Dhaka is an ECE setting providing services that share characteristics of ISCED level 01 (UIS-UNESCO, 2011) and offers services to children between six months and six years’ operating from 06 AM to 7 PM six days a week. Daycares are separated from preschool settings both in terms of physical distance and pedagogical aims. Preschools are ECE settings providing services that share characteristics of ISCED level 02 (UNESCO, 2011) and offer preschool classes to children aged three to five years. Three-year-olds attend the class labeled Play Group (PG), four-year-olds, in the class labeled Nursery (N), and five-year-olds, in the class labeled Kindergarten (KG). Kindergarten classes are divided into Kindergarten 1 (KG1) and 2 (KG2). KG2 functions as an additional preparation before pre-primary enrollment. Each preschool class is offered twice a day in which children are enrolled in one of the widely adopted timeslots. The early timeslot, the 'morning batch' from 10 AM to 12 PM, or the 'afternoon batch' from 1 PM to 3 PM where children attend a two-hour class five days a week. Enrollment fees are a maximum of 15000TK (125 euros) and monthly fees of 8000TK (65 euros). The Bangladeshi median wage is 200 euros/month. Sometimes, preschool services (PG, N, KG1) are offered within the same physical facility, or individual preschools offer only one type of preschool class, for example, only catering to 4-year-olds. However, there are multiple gaps while these structures are adopted in each upazila (administrative subunit of a district), creating varieties of system structures on local levels.

Findings also reveal that educational services that are attended by children go beyond daycares, preschools, and pre-primaries. Children below primary school are also attending tutoring services. This finding is important to note since tutoring is not officially part of the educational system. However, by tracing (Barlett & Vavrus, 2017) these services emerge as an integral part of the multiple services children of ECE age attend.

Kadali’s day in Dhaka's ECE system

The comprehensive overview of a composite character representing a day in the life of a child enrolled in education is represented in the form of Kadali emerging through the totality of data and iterative analysis. Table 2 conveys all events involved during one day in the life of Kadali and her close network surrounding ECE attendance. All events carried out are color-coded in the categories: Home/duties (Teal), Commuting (Red), Daycare (Purple), Preschool class (Yellow), Work (Blue), Drop-off (Green), Pick-up (Gray) and Tutoring (Orange) (see Table 2).

Home/duties represent being in the home or carrying out household duties, such as grocery shopping, hobbies, etc. Commuting represents transport in the family driver's car. Daycare represents the time Kadali is attending daycare. The preschool class represents the time Kadali is attending preschool class. Work represents the time the mother or family driver is performing professional work. Drop-off and Pick-up represent the time when Kadali is being dropped off/picked up vis-a-vis when a stakeholder is dropping off / picking her up. Tutoring represents the time when the Kadali is attending tutoring.

Table 2. A day in the ECE system

Kadali's day centers around ECE attendance (purple, yellow, and orange). In the morning, Kadali and her mother exit the apartment building and the family driver picks them up on the busy street. They drive the 20-minute route arriving at the site of the daycare at 07.30. Kadali and her mother pass through the metal gate at the daycare, pass the derwaan (security guard) and sign in the visitor's book. Up the stairs, they are received by the daycare staff. The staff exchanges a few words with the mother and lifts Kadali in her arms. While Kadali is being dropped off by her mother at daycare, the grandmother is cleaning up at home. The family driver has been circulating outside the daycare and again picks up the mother to rush through traffic for the mother to arrive at her workplace at 08 AM. The family driver then circles back to Kadali's home to collect the grandmother. Little before 09 AM, they leave the apartment again to pick up Kadali from daycare to take her to the preschool class starting at 10 AM. The grandmother enters the daycare, where the hallway is filled with children of different ages, 3, 4, and 5-year-olds, all putting on their backpacks to go to their preschool classes. She spots Kadali sharing a staff member's lap and having her tiffin snack as she is prepared to go to the preschool class.

Moving through traffic, the building of her preschool rises at a distance. The drop-off is smooth as her preschool teacher grabs Kadali's hand, leading her into circle time, where 20 other children await. The children in Nursery, Kadali's preschool class for 4-year-olds, are busy singing while the Kindergarteners, the 5-year-olds, pass in a straight line following their teacher to their designated classroom. Kadali joins in singing the famous rhyme Haat-tim-a-tim-tim (They Lay Eggs) while the teacher gesticulates energetically in the middle of the circle of children. The grandmother heads out on the busy street towards the market to buy groceries while the family driver goes for an early lunch before commuting to pick up the mother from her work. Shortly before noon, the mother leaves her work and commutes with the family driver to pick up Kadali, whose preschool class finishes at noon.

Kadali's preschool class has ended, and she joins her best friend from Kindergarten class in climbing the plastic slide as all the children are let out from their separated classrooms into the joint space awaiting their parents. The line of mothers and grandmothers awaiting children makes the hallway crowded. One by one, preschool teachers bring Playgroup, Nursery, and Kindergarten attendees to their family members to be picked up. Kadali is tired but happy, showcasing her art craft, a hungry caterpillar, while her mother tries to feed her some bhorta. They commute and arrive at the tutoring service, which is part of an international franchise, as they do three times a week. In Kadali's tutoring, they focus on mathematical and reading skills in preparation for the primary school enrollment interview in a few months. Tutoring is more formal and stricter than preschool class, with lots of homework. Kadali sits by a desk that is not occupied while the tutor asks them to collect 'worksheet number 16'.

While Kadali grabs 'worksheet number 16' her mother commutes back to her work in the family driver's car, who drops her off and directly heads to pick up the grandmother, who is still at the market, to go pick up Kadali again, as tutoring class only lasts for an hour. The grandmother leaves the groceries in the car, exits it, and rushes up the stairs of the tutoring setting. Kadali still sits by her desk with a packed folder of worksheets to bring home. They return to the car, and Kadali receives some Amitti sweets from her grandmother's grocery bags. They commute back to the daycare where Kadali is united with the two-year-olds who have been at daycare throughout the day, as no preschool class is available for children under the age of three. They sit around a round wooden table and the caregiver brings colored pencils from the hidden spot on top of the large cabinet. In the meantime, the grandmother returns home to clean vegetables and prepare meat from the market and returns to pick up Kadali shortly before 5 PM. Together they commute home through the smog-filled rush-hour air and arrive home at 5.30 PM. The family driver drives to pick up the mother from her work and brings her home, where the family members are gathered for dinner preparations.

Discussion

By viewing the child as a relational ethnographic unit ‘going through the system’ using Child Standpoint Theory (Medina-Minton, 2019) several facets underpinning ECE are made visible by showcasing a child 'lifeworld' inclusive of contextual elements that form the conditionality of a child's ECE educational pursuits. It is noteworthy that while the routines, schedules, and opening hours of individual ECE settings may not inherently embody systemic features, an analysis of how multiple adjacent ECE settings intersect from the position of the child, the systemic features emerge together creating the structural conditions in which the child is situated. Through analysis, a deeper understanding of how these systemic features collectively contribute to shaping the environment in which the child is situated during the day becomes apparent. The facets made visible are the multiple transitions the child undergoes during the day, and, an over-reliance on the family to enable transportation between ECE daycare, preschool, and tutoring. In the intersection between facets that condition ECE education in the broader context, viewing the child as core in ECE also makes visible facets related to broader questions of educational attainments. As ECE settings are separated, viewing the child as core allows the entangled researcher (Sobe & Kowalczyk, 2018) to posit the child’s exposure to educational curricula that they encounter during a day using (Barlett & Vavrus, 2017) across in-situ and ex-situ analysis. Following the approach suggested in this paper, further investigation coupled with policy studies can allow for an in-depth analysis of contextual elements and local facets underpinning ECE. Together the three-folded approach allows us to capture inside perspectives while at the same time going beyond an individual child's experience of it, it can provide researchers and policymakers a tangible way to gain valid insights into different ECE systems for comparative purposes. Insights that neither are visible through the perspectives afforded by small ethnographic studies (e.g., Kousholt, 2019) nor policy approaches due to system messiness (Guevara, 2022). Through the suggested approach, ethnographic insights could be ‘upscaled’ shifting ethnographic smallness towards a scale beyond, with the possibility of pursuing comparability between contexts. For future studies with the child positioned as the core in ECE, each contextual element (as partly visualized in the color-coded blocks) can be compared across diverse ECE systems for a deeper understanding of the conditionality underpinning ECE. Moreover, there are several limitations to discuss including further exploration of Child standpoint theory (Medina-Minton, 2019). In the current study, there are limitations upon the limited contextual details in the case of Bangladeshi ECE and ethical considerations in depicting the child in the middle-class bracket while vast inequalities prevail at all levels of Bangladeshi society. Limitations also arise in the risk of biases, both during phases of entangling and detangling, of interpolating what is happening in practices as an ethnographer.

Detangling messiness

Furthermore, ECE systems are complex phenomena, and as argued in this study, system messiness conditions scholarly investigations. The complexity of educational systems has been described by several educational researchers and Schuelka and Engsig (2022), in their novel contribution to the complex educational systems analysis (CESA3) builds on Amaral and Ottino's (2004) depiction:

A complex system is a system with a large number of elements, building blocks or agents, capable of interacting with each other and with their environment. The interaction between elements may occur only with immediate neighbors or with distant ones; the agents can be all identical or different; they may move in space or occupy fixed positions, and can be in one of two states or of multiple states. (p. 148)

To which, Schuelka and Engsig (2022) adds:

Complex systems are open and nested, meaning that there is little to no boundary between elements and surroundings, between inputs and outputs, and elements within the system are complex systems within complex systems ever unfolding like a fractal. (p. 452)

However, the concept of messiness appears to contradict Schuelka and Engsig’s (2022) innovative proposal of the unfolding fractal. A fractal, often observed in the structures of snowflakes, is a figure where similar patterns reoccur at different scales, thus suggesting a logic in the reproduction of these patterns. In contrast, the notion of messiness in ECE systems would suggest the lack of logic or similarity between that which is unfolding within the system. This messiness in ECE sectors poses challenges for scholarly inquiry and comparisons, as shown in the current study. Furthermore, in the pursuit of analyzing complex systems, Schuelka and Engsig (2022) also draw on Barlett and Vavrus’s (2017) comparative case study approach that traces the linkages and examines phenomena across multi-sited, multi-level, socio-cultural, and historical dynamics with various methodological options. However, ECE messiness presents a Wicked Problem for comparative ECE methodology, and more studies are needed to understand how the complex systems of ECE create and condition educational experiences. Through the use of combined methodological tools, ethnography, and Child standpoint theory, this study presents an approach to unraveling messiness that places the child as the core of ECE, and allows for the fractals’ around them to become the object of study. This perspective allows for the child to become a relational ethnographic unit through which comparisons across diverse ECE settings can be made from the position of the child enrolled in education.

References

Alanen, L. (2011). Editorial: Critical Childhood Studies? Childhood, 18(2), 147-150. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568211404511

Amaral, L. A. N., and J. M. Ottino. (2004). Complex Networks: Augmenting the Framework for the Study of Complex Systems. The European Physical Journal B 38: 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjb/e2004-00110-5

Anckar, C. (2008). On the Applicability of the Most Similar Systems Design and the Most Different Systems Design in Comparative Research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11(5), 389-401. https://doi.org10.1080/13645570701401552

Akhter, M., & Chaudhuri, J. (2013). Real Time Monitoring for the Most Vulnerable: Pre-Primary Education in Bangladesh. IDS BULLETIN, 44(2), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-5436.12020

Aktar, M. (2013). Universal Pre-Primary Education in Bangladesh Background. Child Research Net. https://www.childresearch.net/projects/ecec/2013_07.html

Aronsson, K. (2012). Barnperspektiv: att avläsa barns utsatthet. LOCUS, 24(1–2), 95–111.

Barlett, L., & Vavrus, F. (2017). Comparative Case Studies: An Innovative Approach. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.1929

Bergnehr, D. (2019). Barnperspektiv, barns perspektiv och barns aktörskap – en begreppsdiskussion. Nordisk tidsskrift for pedagogikk og kritikk,5, 49-61. https://doi.org.10.23865/ntpk.v5.1373

Bertram, T., & Pascal, C. (2016). Early Childhood Policies and Systems in Eight Countries: Findings from IEA’s Early Childhood Education Study. Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39847-1

Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Eurydice (2019). Key data on early childhood education and care in Europe, 2019. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2797/958988

Friesen, P., & Goldstein, J. (2022). Standpoint Theory and the Psy Sciences: Can Marginalization and Critical Engagement Lead to an Epistemic Advantage? Hypatia, 37(4), 659–687. https://doi.org/10.1017/hyp.2022.58

Guevara, J. (2022). Comparative studies of early childhood education and care: beyond methodological nationalism. Comparative Education, 58(3), 328–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2022.2044603

IFC International Finance Corporation (2019). Tackling Childcare in Bangladesh: The business benefits and Challenges of Employer-Supported Childcare. https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/mgrt/ifc-tackling-childcare-in-bangladesh-final-report.pdf https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/c2d78774-aaea-4795-82e6-13e47bac3aff/Final+IFC+Tackling+Childcare+Bangladesh+110619.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=mVJydK3

James, A. (2007). Giving Voice to Children’s Voices: Practices and Problems, Pitfalls and Potentials. American Anthropologist, 109(2), 261–272. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4496640

Kim, T. (2014). The intellect, mobility and epistemic positioning in doing comparisons and comparative education, Comparative Education, 50(1), 58-72. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2013.874237

Khondoker, R. (2019). Role of Religious Actors in Educational Provision: A Case Study in Bangladesh Context. Journal of ELT and Education, 2(3), 15-24. https://jeebd.com/wpcontent/uploads/2019/12/JEE-23-2.pdf

Kousholt, D., (2019). Children’s Everyday Transitions: Children’s Engagements across Life Contexts. In M. Hedegaard & M. Fleer (Eds.), Children’s Transitions in Everyday Life and Institutions (pp. 145–166). Bloomsbury Academic. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350021488.ch-007

McFadden, A., Varcoe, C., & Brown, H. (2023). Examining Child-Led Tours and Child Standpoint Theory as a Methodological Approach to Mitigate Asymmetrical Adult-Child Power Dynamics in Ethnographic Research: A Child-Led Tour of Elfish Antics and Sensorial Knowledge. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 22. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069231182878

Medina-Minton, N. (2019). Are Children an Oppressed Group? Posting a Child Standpoint Theory. Child Adolescent and Social Work Journal, 36, 439–447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-018-0579-8

MoPME, NA. (2008) Operational Framework for Pre-Primary Education: Ministry of Primary and Mass Education: Government of The People’s Republic of Bangladesh. http://ecd-bangladesh.net/document/documents/Operational_Framework_for_PPE.pdf

MoWCA, NA, (2009). Comprehensive Early Childhood Care and Development (ECCD) policy framework. Ministry of Women and Children Affairs. Dhaka BG Press: http://itacec.org/itadc/document/learning_resources/project_cd/ELDS%20South%20Asia/Bangladesh.pdf

Perselli, A. K., & Haglund, B. (2022). Barns perspektiv och barnperspektiv: en analys av utgångspunkter för fritidshemmets undervisning. Pedagogisk forskning i Sverige, 27(2), 75-95. https://doi.org/10.15626/pfs27.02.04

Qvarsell, B. (2001). Det problematiska och nödvändiga barnperspektivet. In H. Montgomery & B. Qvarsell (red.), Perspektiv och förståelse: Att kunna se från olika håll (s. 90-105). Carlsson.

Rahman, F., & Kamra, A. (2024, March 16). Why is quality and affordable childcare vital for inclusive growth in Bangladesh? Worldbank Blogs. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/endpovertyinsouthasia/why-quality-and-affordable-childcare-vital-inclusive-growth-bangladesh

Sikder, S., & Banu, L. F. A. (2018). Early Childhood Care and Education in Bangladesh: A Review of Policies, Practices and Research. In M. Fleer & B. van Oers (Eds.), International Handbook of Early Childhood Education (pp. 569-587). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-0927-7_26

Sobe, N. W., & Kowalczyk, J. (2018). Context, Entanglement and Assemblage as Matters of Concern in Comparative Education Research. In J. McLeod, N. W. Sobe, & T. Seedon (2018). World Yearbook of Education 2018: Uneven Space-Times of Education: Historical Sociologies of Concepts, Methods and Practices (pp. 197-203). Routledge.

Schuelka, M. J., & Engsig, T. T. (2022). On the Question of Educational Purpose: Complex Educational Systems Analysis for Inclusion. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 26(5), 448–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2019.1698062

Tobin, J. (2022). Learning from comparative ethnographic studies of early childhood education and care, Comparative Education, 58(3), 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2021.2004357

UIS-UNESCO (2011). International Standard Classification of Education ISCED 2011. UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

UNESCO (2021). Global Education Monitoring Report 2021/2: Non-state actors in education: Who chooses? Who loses? UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379875

UNESCO (2022). Tashkent Declaration and Commitments to Action for Transforming Early Childhood Care and Education. https://www.unesco.org/sites/default/files/medias/fichiers/2022/11/tashkent-declaration-ecce-2022.pdf

Urban, M. (2022). Scholarship in times of crises: towards a trans-discipline of early childhood, Comparative Education, 58(3), 383-401. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2022.2046376

Vandenbroeck, M. (2020). Early Childhood Care and Education Policies that Make a Difference. In R. Nieuwenhuis, & W. Van Lancker (Eds), The Palgrave Handbook of Family Policy (pp. 169-191). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54618-2_8

World Bank (2020). The Landscape of Early Childhood Education in Bangladesh. Washington. DC eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1596/33465