Vol 4, No 3 (2024)

https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.5937

Article

Global asymmetries in international doctoral education: Dissertations on education development in Africa at Finnish universities

Elizabeth Agbor Eta

University of Helsinki/AMCHES, University of Johannesburg

Email: elizabeth.eta@helsinki.fi

Nico Stockmann

University of Helsinki

Email: nico.stockmann@helsinki.fi/n.stockmann@zeppelin-university.net

Hanna Kontio

University of Helsinki

Email: hanna.kontio@helsinki.fi

Elina Lehtomäki

University of Oulu

Email: elina.lehtomaki@oulu.fi

Abstract

Critical discourses of internationalisation of higher education and decoloniality have motivated this study unfolding global asymmetries present in Finnish doctoral education in the field of educational sciences. The data are doctoral dissertations related to education development in Africa completed at Finnish universities between 2000–2021 (N=100). We first describe the regional distribution and educational contexts where the research is located through a content analysis. Second, we conduct a network analysis of the institutional affiliations of co-authors of article-based dissertations, supervisors, and examiners of the doctoral dissertations and map the institutional connections in doctoral education. Then we present and discuss the findings from the content analysis, the dissertation mapping, and the institutional network analysis against the discourses of internationalisation and decoloniality that influence doctoral education in Finland and beyond. Finally, we reflect on implications for internationalisation of doctoral education in internationalised contexts, especially in North-South collaborations.

Keywords: doctoral education, internationalisation of higher education, decoloniality, network analysis, North-South collaboration

Introduction

This article applies a critical social studies approach to analyse the internationalisation of higher education (HE) focusing on doctoral education in Finland. The number of international students enrolled is a key indicator of the level of internationalisation in HEIs (Shen et al., 2016). Moreover, ‘international outlook’ and impact are factors measured in global rankings (see e.g. Times Higher Education World University Rankings, 2023) which influence potential funders, applicants and mobility trends. HEIs worldwide have embraced the mission of internationalisation, with doctoral education as part of this process. Following this trend, attracting international doctoral students and aiming for global impact are both key components of Finland’s HE internationalisation vision (MEC, 2022).

Critics draw attention to the Western-centric nature of internationalisation, which produces global asymmetries and coloniality (Gumbo et al., 2024; Haapakoski, 2020; Stein & De Andreotti, 2016; Woldegiorgis & Scherer, 2019) in knowledge production, participation, and dissemination. Decolonial critiques highlight how HE internationalisation reproduces unethical practices, including colonialism, racism, and social injustices (Haapakoski, 2020; deWit & Altbach, 2021). Maringe (2022, p. 251) argues that internationalisation can reinforce the colonial goal of Western knowledge domination, while decolonisation seeks to break these chains. Addressing these ethical challenges requires examining global power asymmetries and colonial legacies (Haapakoski, 2020; Maringe, 2022; Woldegiorgis & Scherer, 2019).

In this study we explore the asymmetries in the context of doctoral education, which is a central space of the internationalisation of HE in Finland and beyond. As internationalisation is recognised central to developing and delivering quality doctoral education, HEIs are recommended to consider their international profile in developing international doctoral education in a way that allows international engagements of supervisors, and students through institutionalised collaborations (European University Association, 2015). Internationally, the duration of doctoral studies and the format of dissertations are transforming. The globally influential Bologna Process defines doctoral degrees as three years long (Nerad, 2020), but in practice, the duration varies widely due to doctoral students’ funding and employment conditions and publication structures. Traditionally, dissertations were monographs by the doctoral researcher under a supervisor’s guidance, but now they may also be article-based, consisting of published articles or book chapters with multiple authors (Grant et al., 2022). Changes are also observed in supervision practices from a one supervisor to co-supervision models (Grant et al., 2022; Kálmán et al., 2022; Nerad, 2020). These transformations have invited new international contributors to doctoral dissertations in roles of co-authors and supervisors.

Studies on international doctoral education have explored various aspects, such as factors influencing the enrolment of international doctoral students (Taylor & Cantwell, 2015), international student recruitment policies (Jokila, 2020), reasons for international doctorate recipients to remain in the host country (Kim et al., 2011), identity trajectories of doctoral students abroad (Peura, 2022), and comparison of international doctoral students among a country’s doctorate recipients (Shen et al., 2016). Despite the interest in international doctoral studies, there appears to be a lack of attention to the networks of relevant contributors involved in the process. Therefore, our paper focuses on networks of key contributors to the progression and completion of doctoral dissertations that have been produced in internationalised settings. These include supervisors, co-authors of article-based dissertations, and examiners (pre-examiners, and opponents) of dissertations. Examining the connections, as well as the representation of these diverse contributors operating in an internationalised context is crucial for deepening our understanding of the dynamics of HE internationalisation, particularly in the context of international doctoral education.

Drawing from the decolonial critique of internationalisation of HE and international doctoral education, we contextualise our analysis on doctoral research on education development in Africa completed within Finnish HEIs. Moreover, Finland’s development policy has defined Africa and education as priorities in development cooperation which is further confirmed in the country’s Africa Strategy (Finnish Government, 2021). Also, major international education development actors emphasize Africa (European Commission, 2023; UNESCO & African Union, 2023; World Bank, 2022). It could be assumed that these policy objectives are present and influence the internationalisation of HE, including doctoral education in Finland.

With the aim to unfold the global asymmetries present in Finnish doctoral education in the field of educational sciences, we have defined two specific research questions:

1. How can the research contexts in doctoral dissertations related to education development in Africa, completed at Finnish universities, be mapped and characterised?

2. What are the geographical and institutional connections in the processes of supervising and examining doctoral dissertations on education development in Africa?

Finnish higher education internationalisation strategy: Africa a region of interest

In the Finnish context, internationalisation of HE is a major policy goal seen both as a source of revenue and a means to enhance global competitiveness (Välimaa & Weimer, 2014). The Ministry of Education and Culture’s (MEC) 2022 vision aims to position Finland as ‘a competitive economy that attracts [international] talent’, ‘creates new knowledge and competence to respond to global challenges and boost Finland’s competitiveness’ and ‘broaden their cooperation with advanced research organisations and with actors in developing countries’ (MEC, 2022, pp. 1–2). Recently, more attention has been given to creating more equitable partnerships between HEIs in Finland and in the global South (Brito Salas & Avento, 2023).

Doctoral education presents an internationalised space in Finnish HE. In 2021, 24% out of 19,000 doctoral students enrolled in Finnish universities were other than Finnish nationals. Doctoral students with employment are placed on stage one in a four-stage career path of academic staff. In 2022, 41% of the first stage employees was non-Finnish nationals, as opposed to only 11% in the highest stage (stage 4) (Kannisto et al., 2023). Engaging with countries of the Global South is an integral part of Finnish HE institutions’ internationalisation strategies. Regarding the reception of international students, a 2013 study (Välimaa et al., 2013) indicates that among the top 20 nationalities in international degree programmes at universities and universities of applied sciences, five were from African countries. In 2021, nationals of African countries accounted for 9% of international doctoral students in Finnish universities (Kannisto et al., 2023).

Besides student mobility, the increasing policy emphasis on Africa, as indicated in Finland’s Africa Strategy (Finnish Government, 2021) followed by institutional strategies (e.g., University of Helsinki, 2021) has strengthened the institutional internationalisation focus on Africa. In the case of the African continent, government funding has played a major role in Finnish HE internationalisation. Important resources for internationalisation include the ‘HEI ICI’ and ‘HEP’ programmes for HE capacity development, funded by the Finnish Ministry for Foreign Affairs through its development cooperation funds and administered by the Finnish National Agency for Education (EDUFI), and the innovation-focused ‘Team Finland Knowledge’ programme (EDUFI, 2021). In addition, the ‘Global Networks’, funded by the MEC, have provided new resources for partnerships and collaboration with universities in African countries (MEC, n.d.).

The described policy context seems generally supportive of internationalisation and Finland-Africa development cooperation in HE. Doctoral education, as an intersectional space of international student mobility, internationalisation policies, institutional partnerships, public research funding and publishing, is a key context for internationalisation in HE. In this study, by examining completed doctoral dissertations in Finnish HE in the field of educational sciences, we depict the scope of research on education development and the connections between Finnish and African institutions.

Internationalisation and decolonisation of doctoral education

The global knowledge economy is organised hierarchically in its production, participation (Haapakoski, 2020; Woldegiorgis, 2023) and dissemination processes with dualistic divide between the North and the South. This division highlights inequalities and power dynamics within global education politics, academic partnerships, and internationalisation activities with core countries in the North dominant in producing, prescribing, and disseminating knowledge (Altbach, 1998). Core countries in the North dominate knowledge production and dissemination, while periphery countries in the South are seen as consumers, producing little original knowledge (Altbach, 1998). Efforts to promote knowledge transfer from the North to the South, aimed at narrowing the development gap (UNESCO, 2009), perpetuate a passive dependency on the North.

In global HE context, there is a push to decolonise internationalisation (Haapakoski, 2020; Maringe, 2022), including doctoral studies (Grant et al., 2022). Maringe (2022) argues that coloniality cannot be ignored in the study of internationalisation of HE, as its roots, drivers, and priorities are defined by HE in the Global North. Further, while internationalisation discourse is based on established, main-stream theoretical frameworks, decolonisation is less securely supported by fringe theories of critical thought (Maringe, 2022). Maringe’s approach to decolonisation interrogates ‘the coloniality of being, of knowledge and power in academy in order to create a new terrine of reason which prioritises the growth of local knowledge in the global South through a purposeful new engagement with the global north’ (Maringe, 2022, p. 254). Adopting a decolonial approach to internationalisation (Maringe, 2022), we focus on issues of knowledge asymmetries, epistemic hegemony, and reciprocity in international doctoral education (Asare et al., 2022; Teferra, 2016; Unterhalter & Howell, 2021).

Reciprocity in internationalisation refers to equitable benefit distribution among all partners (Woldegiorgis & Scherer, 2019). A decolonial perspective challenges the idea that internationalisation is neutral and equally beneficial (Haapakoski, 2020; Teferra, 2008). The global knowledge economy’s hierarchical structure leads to unequal benefit distribution (Bray, 2014; de Wit & Altbach, 2021), evident in global academic mobility and publishing patterns. While international mobility drives internationalisation, it has historically been unidirectional, flowing mainly from the South to the North (Jones & de Wit, 2021; Maringe, 2022; Teferra, 2008; UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2022). Despite evolving dynamics (Jones & de Wit, 2021), inequalities persist.

Publishing within international academic partnerships, including doctoral dissertations between the North and South exhibits inequality and perpetuates asymmetries. While research is key to publishing, it is a means to formally organise, disseminate, and establish knowledge (Teferra, 2008, p. 59). Authorship is central to legitimising academic expertise and the scientific reward system. However, agreements on authorship often undervalue scholars in the South (Teferra, 2016), with persistent imbalances favouring certain countries over others (Asare et al., 2022). Researchers from Southern institutions are often limited to data collection roles, without rights to data analysis and publishing (Asare et al., 2022; Ishtiaq & Haque, 2016; Trahar et al., 2019).

African HE is part of a larger global HE system, but with limited participation and noticeable consequences. Woldegiorgis (2023) notes that African HE needs to establish partnerships with foreign HE systems to enhance the production, dissemination, and utilisation of knowledge, thereby maximising the benefits of internationalisation. However, even within these partnerships, African HE assumes the contradictory position of the most internationalised system but the least internationally engaged, rendering it vulnerable to global influences and lacking agency (Teferra, 2008). Thus, internationalisation processes must be grounded in principles of mutuality, reciprocity, and shared responsibility; otherwise, the relationship between the Global North and South risks perpetuating neo-colonial dynamics (Woldegiorgis, 2023). Acknowledging the critique of internationalisation as an aim taken for granted (Haapakoski, 2020; Teferra, 2008) and being driven by economic benefits and competitive advantage (Maringe, 2022; Woldegiorgis, 2023), decolonial discourses that question post-colonial thinking should be encouraged. For the discourses of internationalisation and decolonisation to co-exist, Maringe (2022) points to the importance of divergent thinking/approaches. In this study, we examine how doctoral education in Finnish HE enables this.

Integrating decolonisation and internationalisation can focus on knowledge production, university strategies, recognition of (implicit) knowledges and values, local identity, global positioning, and power dynamics (Maringe, 2022). Our study explores the integration of decolonisation and internationalisation of Finnish HE through a critical lens provided by data on doctoral education related to education development in Africa. Following Löfström and Pyhältö (2021), the quality and ethics of collaboration in doctoral supervision as well as in the co-authorship and examination practices require critical examination.

Methods

Data for the study is based on secondary archival data, which provides readily available and rich data that can be analysed from a perspective that was not considered during data gathering (Smith, 2008) and allows us to analyse trends and insights into research topic. The data for this study consisted of already defended and published doctoral dissertations on education development in Africa completed at Finnish universities between 2000 and 2021. As the published doctoral dissertations include mentions of the various contributors that have been involved in the process, including supervisors, pre-examiners, co-authors, and opponents, the information provided in the dissertations offers an overview of the doctoral education landscape, particularly concerning the situatedness and connections of the contributors.

To select the doctoral dissertations for inclusion in this study, three criteria were considered:

1. All dissertations from faculties of educational sciences focusing on Africa from the eight universities recognised by the Finnish Multidisciplinary Doctoral Training Network on Educational Sciences.[1]

2. Dissertations completed in other faculties and universities in Finland that focus on education development in Africa. We considered the broad fields of education in ISCED 2013.[2]

3. Dissertations that included education-related keywords[3] in the titles, keywords, abstracts, and objectives as outlined in criterion two.

A total of 100 doctoral dissertations completed in nine Finnish universities met the established criteria. The analysis was done in two parts. First, a content analysis was conducted to systematically describe the data (Schreier, 2012). We focused on the African national and regional research contexts of the dissertations, the researched education sub-sectors—following the Continental Education Strategy for Africa 2016–2025 (African Union, 2015)—and the key actors involved in the doctoral process, such as supervisors, pre-examiners, opponents, and co-authors of article-based dissertations. The necessary information was extracted from the first pages of the dissertations where details about the supervisors, pre-examiners, and opponents were provided. Additionally, the acknowledgment sections of the dissertations offered valuable data on these contributors as well as others instrumental in the process. For dissertations where such information was missing, we gathered them from the coordinators of doctoral programmes within the faculties and some directly from the graduates.

Nonetheless, there were still instances of missing data. Not all the graduates provided the requested information, and coordinators were unable to find all the required information, particularly for dissertations completed in the early 2000s. The explanation was that ‘in previous years, the opponent was not mentioned in the actual book, and some of these are so “old” that I wasn’t able to locate the paperwork’ (Doctoral programme coordinator’s email to first author, December 18, 2023). Notwithstanding, this analysis provides valuable insights into the contributors involved in doctoral dissertations process. Authorship data for article-based dissertations were retrieved from the list of original publications included in the dissertation and further investigation involved identifying the affiliations of the authors by searching the articles in the respective journals.

Second, we employed a network analysis to map and understand the global connections of institutional affiliations among the various contributors in the doctoral process—i.e., article co-authors, supervisors, pre-examiners, and opponents. The approach aimed to shed light on the overall landscape of doctoral dissertations at Finnish universities, highlighting the connections, directions, and links, particularly with regards to the representation of African institutional affiliations within the key roles of the doctoral process vis-à-vis other regional institutional affiliations. To analyse the global dynamics in institutional networks, we coded the institutional affiliations of persons involved in each of the above-mentioned roles in the dissertation process. Different from, for example, a typical individual-based affiliation network, our focus was on the aggregation of institutional affiliations with additional node characteristics (Pfeffer, 2017). The resulting network places individual institutions as nodes and the respective doctoral dissertation process relationships of their affiliated individuals as edges. It is important to highlight that in this one-mode network, each individual’s affiliation is tracked separately, which means that the number of individuals in the dataset is smaller than the number of mapped affiliations. The typology used to further cluster the institutional nodes has been based on the continent of the respective institution[4] and by the function as an institution that awarded one of the collected doctoral degrees (degree awarding Finnish HEIs, DA-HEIs).

We then used Gephi (Bastian et al., 2009) to analyse and visualise four role-specific networks: an undirected network of co-authorship affiliations (for article-based dissertations; n=44) as well as three directed networks for the supervisor, and examiner (pre-examiner, and opponent) affiliations. The differentiation between an undirected and the directed networks reflects our understanding of co-authorship relations as being bi-directional, in contrast to the directed nature of the other three roles (e.g., from supervisor to supervisee). In the latter cases, the networks’ directedness allowed for a differentiation between the reception and provision of supervision and examination roles through the institutional nodes’ in-and out-degree.[5] To distinguish collaboration patterns beyond the regional typology of institutional nodes in the undirected co-authorship network, we conducted a community detection (Newman, 2006) using Gephi, highlighting clusters of dense collaboration.

To analyse and describe the global distribution and importance of the regionalised nodes, we relied on the following centrality measures (Knoke & Yang, 2020). Degree refers to the number of direct connections a node has with other nodes in the network, while the weighted degree refers to the sum of the weights of all edges connected to a node, representing the total strength of its connections—in the case of this analysis between different institutions. Lastly, we used betweenness centrality, which measures the extent to which a node lies on the shortest paths between other nodes, to identify important nodes/institutions that have a role as a connector within the network.

Findings

Dissertation overview: Research context, regional distribution and education levels researched

Findings from the content analysis of the 100 dissertations in terms of country context and education sub-sectors are presented in Table 1.

The analysed dissertations focused on 17 African countries. Individual dissertations covered 1–4 case countries. Tanzania was the most researched country context with 33 dissertations, followed by Malawi with 13 dissertations, both countries located in Eastern Africa. The significant regional focus on Eastern Africa, comprising 50% of the dissertations research context, can be attributed to Finland’s development policy which prioritises countries from this region and enables more funded cooperation and research projects focusing on that region. In contrast, six countries are represented by individual cases that do not indicate a connection to broader partnerships. Anglophone countries in Africa are emphasised in the dissertations. Some multiple case study dissertations focused solely on African countries while others included African countries along with Finland or other European countries.

The dissertations covered various levels of education including primary education, secondary education, higher education, technical and vocational education, and non-formal education (CESA 15-16). The most researched education sub-sectors were informal and non-formal education and training (34), tertiary education (33) and primary education (26). Secondary education was a focus of 11 dissertations while TVET and pre-primary education were the context of very few studies.

Table 1. Dissertation country contexts (n=17) and education sub-sectors

|

Country context |

Education sub-sector |

||||||

|

|

Country context (total) |

Pre-primary education |

Primary education |

Secondary education |

Technical and vocational education and training |

Tertiary education |

Informal and non-formal education and

training |

|

Education sub-sector (total) |

1 |

26 |

11 |

2 |

33 |

34 |

|

|

Tanzania |

33 |

9 |

4 |

1 |

12 |

7 |

|

|

Malawi |

13 |

13 |

|||||

|

Ghana |

9 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

|||

|

Ethiopia |

8 |

5 |

1 |

2 |

|||

|

Nigeria |

7 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

|||

|

Zambia |

7 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

|||

|

Kenya |

6 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|||

|

Cameroon |

5 |

2 |

3 |

||||

|

Uganda |

5 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

|||

|

Namibia |

5 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

||

|

South Africa |

4 |

1 |

3 |

||||

|

Gambia |

1 |

1 |

|||||

|

Liberia |

1 |

1 |

|||||

|

Senegal |

1 |

1 |

|||||

|

Egypt |

1 |

1 |

|||||

|

Mozambique |

1 |

1 |

|||||

|

Somalia |

1 |

1 |

|||||

The fields of research within each education sub-sector were broad, spanning education, teaching and learning, business, agriculture, health, information and communication technology, architecture, and management. These broad fields can be attributed to the fact that the doctoral dissertations on education development in Africa have been completed across different faculties.[6] The research areas covered by these dissertations were grouped into four broad categories:

· Teachers (teacher training, professional development, professional qualifications)

· Pedagogical practices (teaching methods, inclusion practices, multilingual practices, aggression and punishment, wellbeing, technology design, healthcare practices and nutrition programme development, HIV/AIDS)

· Learning (literacy, academic performance)

· Policy and programmes (education policy, educational programmes, programme evaluation, enrolment and graduation, institutional management, curriculum, education relevance, development cooperation and academic partnerships, sustainable development)

The dissertations present a broad spectrum of research topics and contexts—reflecting national and international policy priorities and contextual challenges. This may imply that doctoral students have been able to pursue research topics of interest and that are relevant to the country contexts rather than strictly aligning with the focus areas of educational research conducted in the Finnish institutions. The high proportion of dissertations located in the informal and non-formal education sector points to the importance of understanding education beyond formal institutions.

Author affiliation networks of article-based dissertations

This section provides an overview of the co-authorship network, followed by an analysis of the different regions and categories within the network. Finally, we examine the identified communities across the co-authorship relations.

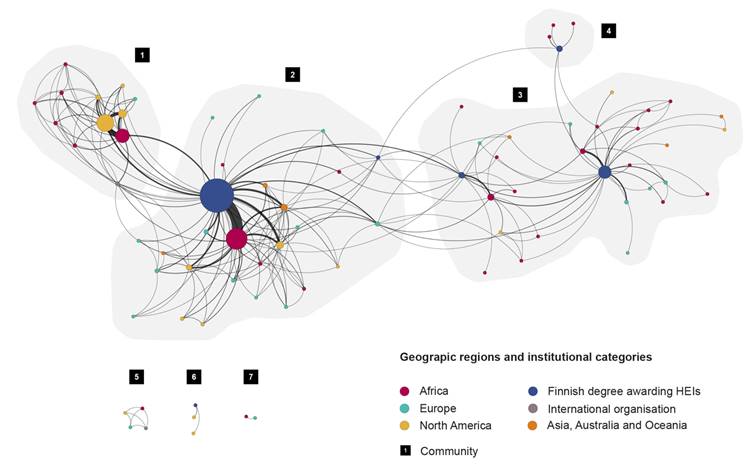

Figure 1. Network graph of co-authorship relations of article-based dissertations

In our analysis, we categorised dissertations based on their type, distinguishing between article-based and monographs. Out of the total 100 dissertations completed during the study period, 56 were monographs while the remaining 44 were article-based, including 193 articles with three to seven articles per dissertation. Our focus here is on the network of co-authorship of article-based dissertations.

Out of the 193 articles, 174 were co-authored while 19 were sole authored. The 193 articles were written by 230 authors from 83 institutions. There were cases of multiple affiliations per author, ranging between one and three affiliations. A network plot of the authors’ institutional affiliations is shown in Figure 1.

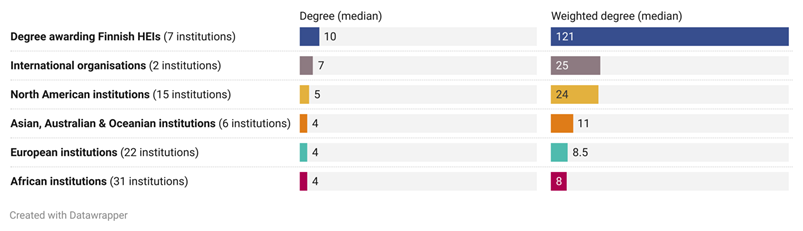

Comparing the degree distributions across the mapped regions and institutional categories confirms a considerable discrepancy in the network. Figure 2 provides a region/category-specific comparison of median degrees and median weighted degrees. As might be anticipated from their pivotal position in the dissertation process, the group of seven DA-HEIs, representing only 8.4% of the network’s nodes/institutions, holds the highest median degree (10) and median weighted degree (122).[7] It is, however, particularly noteworthy that there are significant differences between the remaining groups. International organisations (2.4% of nodes) and North American institutions (18.1% of nodes), exhibit comparably high median degrees (7 and 5, respectively) as well as strong inter-institutional ties, as reflected in their median weighted degrees (25 and 24, respectively). In contrast, the largest groups in the network, namely African (37.4% of nodes) and European (26.5% of nodes) HEIs, show median degrees of 4, but exhibit considerably lower strengths of these ties (weighted degrees of 8 and 8.5, respectively). As will be shown in the following paragraphs on community detection, we attribute this difference in part to the strong involvement of North American institutions and the international organisation in community one.

Figure 2. Co-authorship network median degree and median weighted degree by region/category

In terms of community structure, we detected seven communities within the co-authorship network (see Figure 1), out of which three (communities five to seven) are minor detached networks with two to four nodes. These are nonetheless mapped here as they depict the relations of these institutions—or the lack thereof—to the rest of the network. The main network is thus structured through four communities, most of which are centred around one of the DA-HEIs. These institutions can be furthermore identified through their prominent betweenness centrality values (Tampere University[8] BC=0.33 in community two; University of Eastern Finland[9] BC=0.288 in community three; University of Jyväskylä BC=0.068 in the small community four). Community one marks an exception as it contains mainly African and North American institutions (but no Finnish HEI) and is primarily connected to the rest of the network through the key Finnish institution in community two. Lastly, analysing the betweenness centrality, two of the DA-HEIs as well as one British HEI function as key connecting nodes between communities two and three, while one African HEI marks a particularly central node in community two. Other nodes remain marginal in terms of betweenness centrality.

The visual inspection and centrality measures within the respective communities furthermore show that particularly communities one and two are highly interconnected in contrast to communities three and four. The latter two exhibit a pattern that is concentrated on their respective central DA-HEIs and show few connections between international co-authors’ institutions. Comparing the effect of these co-authorship collaboration patterns on the role of African institutions within each community, we found a divide in the prominence of African institutions, depending on the community structure. The less Finnish HEI-centric communities one and two exhibit a considerably higher median degree and median weighted degree[10] for their respective African institutions (community one: med. deg.=8.5, med. weighted deg.=30; community two: med. deg.=6, med. weighted deg.=22) in contrast to the two communities with a structure that is centred on the DA-HEI (community three: med. deg.=3, med. weighted deg.=5.5; community four: med. deg.=2, med. weighted deg.=6.5).

Networks of supervisors and examiners

We next focus on the formal roles in the processes of supervising and examining the doctoral dissertations. As a result of the doctoral candidates’ affiliations with their DA-HEI, the respective networks centre around the DA-HEI nodes. Therefore, the focus here is on the regional share within the three categories of appointments (supervisor, pre-examiner, opponent) with a particular emphasis on the representation of African institutional affiliations.

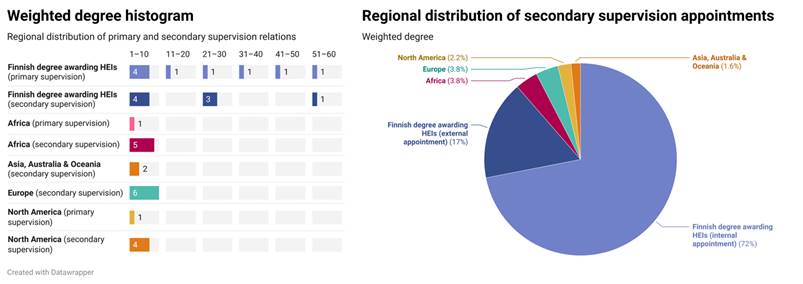

Supervision relationships

We analysed the international network around the supervision of 100 doctoral dissertations. We identified the institutional affiliations of 125 primary and secondary supervisors, who engaged in 193 supervision relationships (of those, 100 as primary, and 93 as secondary supervisors) with affiliations in 28 institutions. The latter comprised Finnish and international HE institutions as well as other international organisations. The number of supervisors for each dissertation ranged between one (25 dissertations) and three (16 dissertations), with exception of one dissertation supervised by four supervisors. 58 dissertations were supervised by two supervisors.

We define co-supervision as ‘a form of collaborative supervision where two [or more] supervisors guide and support one supervisee’s research work in a doctoral study’ (Kálmán et al., 2022, p. 452). Given the central role of supervision in the doctoral process, there is a constant call for reinforcement of co-supervision practices to enhance the quality of supervision (Kálmán et al., 2022) and in the context of this study, to enhance the contextual relevance of the resulting doctoral dissertations to serve education development purposes. We contribute to this discussion on co-supervision by asking: where are the co-supervisors institutionally situated/affiliated, and how does the global distribution look like?

As expected in terms of institutional procedures, the primary supervision is almost exclusively located within the DA-HEI: 98% of primary supervisors are affiliated with the respective DA-HEI.[11] While the primary supervisor generally represents the awarding institution, the choices made in secondary supervision constellations can better inform our analysis of global asymmetries in international doctoral education.

Given this focus, also the secondary supervisor affiliations paint a similarly Finland-centric picture with 89% of secondary supervisors being affiliated with one of the DA-HEIs. The remaining share is distributed between affiliations with African (4%), European (4%), North American (2%) as well as Asian, Australian, and Oceanian institutions (1%). Figure 3 illustrates the regional distribution of affiliations in both primary and secondary supervision and by region/type of institution as well as the regional share of secondary supervision relations. We furthermore analysed the composition of the secondary supervision relationships in affiliation with the DA-HEIs to check for the share of internal and external secondary supervisor appointments. Here, we found that an overwhelming 72% of the secondary supervisors are affiliated with the dissertation author’s ‘home institution,’ while 17% of secondary supervisors at the DA-HEIs are affiliated with another Finnish one of the nine DA-HEIs in the sample. This highlights a pattern of predominantly internal appointments of secondary supervisors within the DA-HEIs.

Figure 3. Regional distribution of secondary supervisor affiliations

The analysis of institutional affiliations in supervision relationships highlights the central role of DA-HEIs. Secondary supervisor appointments are predominantly internal (72%), with only 11% affiliated outside DA-HEIs, and a mere 4% linked to African universities.

Examiners network of doctoral dissertations

Examiners play a core function in evaluating doctoral dissertations. This process typically involves two phases and is carried out by academics with expertise in the dissertation’s research area. In Finland, it begins with a pre-examination followed by a public defence with an opponent.

During the pre-examination, two examiners assess the manuscript’s quality, whether it meets the minimum requirements or if it requires revision (University of Helsinki, n.d.). They provide an objective and independent evaluation written statement, highlighting areas of strength and of concern, and recommend whether the dissertation is ready for the public defence. The public defence marks the final stage, where an opponent, appointed by the faculty, examines the thesis in the dissertation defence. Opponents are always chosen from outside the candidate’s home faculty and university. They conduct a thorough academic examination of the dissertation through a public debate and participate in evaluating and grading the dissertation together with the home faculty.

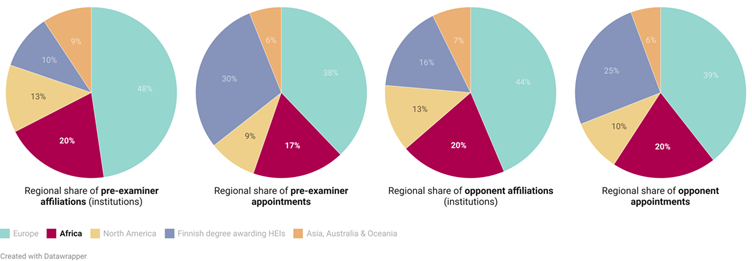

Here, we analyse the network of the pre-examiners and opponents based on their institutional affiliations to highlight the examiners connections and global representation. Among the dissertations in our sample, we identified the institutional affiliations of 171 pre-examiners, who are affiliated with 85 institutions, and 85 opponents, affiliated with 52 institutions.[12] Considering the (sometimes multiple) affiliations and appointments of these persons, the respective networks consist of 193 pre-examiner appointments and 91 appointments of opponents.

The analysis of the regional distributions is based on two directed networks. Figure 4 shows the regional distribution of affiliated institutions (share of nodes) and the share of appointments (regional share of weighted out-degree from pre-examiner/opponent to dissertation author node) for both the pre-examiner and the opponent roles.

Figure 4. Share of reviewer and opponent institutions and appointments

The analysis shows that by far the largest share of pre-examiner as well as opponent roles for these dissertations consists of appointments from European institutions, though without a particular emphasis on certain institutions. Most European institutions see one-time appointments of pre-examiners and opponents. Only 12% of all pre-examiners and 11% of opponents have more than one appointment—however, those institutions with more than one appointment are almost exclusively Nordic HEIs.[13]

In both the pre-examiner and opponent roles, the group of nine DA-HEIs follows the same patterns with a disproportionately large rate of appointments in contrast to a small group of institutions. This effect is particularly visible in the case of pre-examiners in which DA-HEIs make up 10% of the institutions/nodes but hold a share of 30% of the overall pre-examiner appointments. Compared to the other 41 European institutions, which register on average only 1.2 pre-examiner and 1.2 opponent appointments within a large group of institutions, the DA-HEIs register an average of 4.33 pre-examiner, and two opponent appointments in the small group of nine institutions.

The share of African affiliations and appointments marks the third largest group for both the pre-examiner and opponent roles, ranking consistently with 17–20% of the sample. Four out of 17 African institutions saw more than one pre-examiner appointment, making an average of 1.35 appointments per institutions with a maximum number of four appointments. Focusing on opponents from African institutions, three out of 11 saw two opponent appointments per institution, averaging at 1.27 opponent appointments per African institution.

In summary, the analysis of the global representation within the pre-examiner and opponent appointments made by Finnish HEIs highlights a dominance of European institutions. 68% of pre-examiners and 64% of opponents are affiliated with European or Finnish institutions, with the group of four DA-HEIs having a disproportionate presence for both roles. In contest, African institutions receive less than a third of the share of the appointments of European and Finnish institutions, which also manifests in marginal impacts on the institutional level. These findings point towards the question of better utilising the existing connections.

Discussion

The mapping of research contexts of doctoral dissertations on education development in Africa completed at Finnish universities between 2000-2021 indicates a significant regional focus on Eastern Africa, reflecting a connection to the Finnish development cooperation policy and priority countries. Educational sub-sectors of tertiary education, informal and non-formal education and training, and primary education are emphasised. These correspond with the long-standing priorities in international education development. We found dissertations on education development completed in different disciplines and faculties which suggests that education cuts across different sectors of societies.

Our co-authorship network analysis of article-based dissertations show two distinctive collaboration patterns. First, collaborations solely focusing on the central Finnish degree awarding institutions (DA-HEI). Second, communities in which the DA-HEI is collaborating within a wider international network. Furthermore, we highlight the positive impact that the de-centralised structure has on the prominence of African institutions within their respective community. The global distribution of supervision and examiner affiliations highlights a strongly Finland-centric appointment pattern. This discrepancy is particularly present for the appointment of secondary supervisors, which stem overwhelmingly from inside their respective DA-HEI, or from another Finnish HEI while secondary supervisors from African HEIs are the exception rather than the rule. In terms of examiner appointments, we noted a similar trend of underrepresentation of African HEI affiliations, in contrast to a dominance of appointments from European institutions. The findings from the network analysis show the different patterns of global asymmetries in research communities formed by co-authorship, supervision, and examination of the doctoral dissertations. The pattern reflects the common Eurocentric/Western model of doctoral education (Gumbo et al., 2024; Maringe, 2022).

There is increasing critique on the current approaches and models of doctoral education reproducing colonial patterns by ignoring local epistemologies and knowledges, thus failing to create context-relevant knowledge which is necessary for social impact contributing to sustainable development, inclusion and social justice (e.g., Gumbo et al., 2024; Unterhalter & Howell, 2021). Research collaboration, including doctoral education are a key part of Finland-Africa partnerships in HE, aiming to respond to global challenges (MEC, 2022). In our data, the acknowledgement sections of the analysed doctoral dissertations repeatedly emphasised the importance of local experts from the national contexts of their research in understanding the local contexts, facilitating data collection, and providing insights and critique from the reading of manuscripts. It is thus evident that experts within the local research contexts make significant contributions to the doctoral dissertation process. However, this is in stark contrast with formal supervision practices, especially of secondary supervisors’ appointment, that to a great extend exclude academics from African universities. Our research raises critical questions about the doctoral supervision assignment process. Which guidelines and institutional policies exists in selecting supervisors? Can the doctoral researchers propose local experts from their research contexts as official second or third supervisors? How to create enabling/supporting structures to formally recognise the contributions of local experts?

Our findings point to the importance of recognising the knowledge asymmetries present in Finnish and doctoral education. The network analysis on examiners (pre-examiners and opponents) and co-authorship also brings to light issues of knowledge asymmetries, epistemic hegemony, and lack of reciprocity which have been important issues in the recent international research (Asare et al., 2022; Teferra, 2016; Unterhalter & Howell, 2021). The underrepresentation of African HEI-affiliated examiners and co-authors of article-based dissertations in our study is in line with previous research highlighting the dominance of the West in knowledge production and participation (Altbach, 1998; Gumbo et al., 2024; Haapakoski, 2020; Teferra, 2008). Reciprocity, especially as seen in article-based dissertations on education-related topics on Africa but with a limited number of African affiliated co-authors points to the persisting imbalances in HE internationalisation and North-South partnerships (Asare et al., 2022).

The trends revealed in this paper highlight how international doctoral education practices also reinforce ‘the colonial global goal of knowledge domination including its knowledge system’, thus emphasising the need to rethink inclusive ways of ‘breaking the chains of western knowledge domination over post-colonial nations’ through a process of decolonisation that foregrounds local knowledge and allows new kinds of engagements with the global North (Maringe, 2022, p. 254). This kind of inclusive practice may bring in the much-needed reciprocity dimensions into internationalisation practices both in the global North and in the global South (Teferra, 2008). By highlighting the asymmetries in supervision, examination and publication patterns in doctoral education, we invite stakeholders in the doctoral education process to reflect on the persistent colonial patterns of internationalisation and seek to decolonise it with the aim to ‘decentre knowledge that continues to masquerade unquestioned as hegemonic imperialism’ (Kumalo, 2018, p. 13).

Interpreting the findings in the light of Maringe’s (2022) research on decolonising HE, the difficulty to change the global imbalances seems evident due to various systemic factors, encompassing, for example, North-driven funding schemes and publication structures. Therefore, initiating transformation already from the beginning of the doctoral research projects by more equity conscious partnership building and representative international networks to support doctoral research can be an important step towards decolonising doctoral education. Further research is necessary on the important connection of internationalising doctoral education and decolonisation and its influence on global scholarship development. As Maringe (2022, p. 62) notes, ‘Realistically, the benefits of decolonisation tend to be largely intangible, for example, an increased sense of equality, integrity, and identity, attributes which are very difficult to measure but nevertheless crucial and significant’.

Finnish HE institutions are internationally connected through research, providing them with good possibilities to enhance the relevance of knowledge co-created through doctoral research projects. This research based on information in the published doctoral dissertations provides insights into networks and institutional connections of contributors to doctoral dissertations in an internationalised context. These data can be used in future research for a comparative analysis of the Finnish case in relation to other contexts. Further research based on interviews with doctoral dissertation contributors, including the doctorate recipients, and utilising other analytical approaches will provide more explanatory insights into these processes.

We conclude that a critical review and re-design of Finnish doctoral education is necessary to address the perpetuation of coloniality and the widening of global asymmetries in the internationalisation of HE. Reciprocal international collaboration through inclusion of scholars and research communities from African universities in authorship, supervision, and examination are important practical steps in decolonising doctoral education.

Acknowledgements

This study has been funded by the University of Helsinki through the Global Innovation Network for Teaching and Learning (GINTL).

References

African Union. (2015). Continental education strategy for Africa 2016–2025. African Union. https://ecosocc.au.int/sites/default/files/files/2021-09/continental-strategy-education-africa-english.pdf

Altbach, P. G. (1998). Comparative higher education: Knowledge, the university and development. Ablex.

Asare, S., Mitchell, R., & Rose, P. (2022). How equitable are South-North partnerships in education research? Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 52(4), 654–673. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2020.1811638

Bastian, M., Heymann, S., & Jacomy, M. (2009). Gephi: An open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media. https://gephi.org/publications/gephi-bastian-feb09.pdf

Bray, M. (2014). Actors and purposes in comparative education. In M. Bray, B. Adamson, & M. Mason (Eds.), Comparative Education Research (2nd ed., pp. 19–46). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05594-7_1

Brito Salas, K., & Avento, R. (2023). Ethical guidelines for responsible academic partnerships with the Global South. Finnish University Partnership for International Development, UniPID.

de Wit, H., & Altbach, P. G. (2021). Internationalization in higher education: Global trends and recommendations for its future. Policy Reviews in Higher Education, 5(1), 28–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322969.2020.1820898

EDUFI. (2021). Team Finland Knowledge programme. https://www.oph.fi/en/news/2021/new-team-finland-knowledge-programme-opens-possibilities-cooperation-and-mutual-learning

European Commission. (2023, January 26). Quality education in Africa: EU launches €100 million Regional Teachers’ Initiative. Press release. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_288

European University Association. (2015). Principles and practices for international doctoral education. European University Association. https://www.eua.eu/publications/reports/principles-and-practices-for-international-doctoral-education-the-frindoc-project-partnership.html

Finnish Government. (2021). Finland’s Africa strategy: Towards a stronger political and economic partnership (No. 2021:21; Publications of the Finnish Government). http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-383-580-1

Grant, B., Nerad, M., Balaban, C., Deem, R., Grund, M., Herman, C., Aleksandra Kanjuo, M., Porter, S., Rutledge, J., & Strugnell, R. (2022). The doctoral-education context in the 21st century: Change at every level. In M. Nerad, D. Bogle, U. Kohl, C. O’Carroll, C. Peters, & B. Scholz (Eds.), Towards a global core value system in doctoral education (pp. 18–42). UCL Press. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781800080188

Gumbo, M. T., Knaus, C. B., & Gasa, V. G. (2024). Decolonising the African doctorate: Transforming the foundations of knowledge. Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-024-01185-2

Haapakoski, J. (2020). Market exclusions and false exclusions: Mapping obstacles for more ethical approaches in the internationalisation of higher education [Doctoral dissertation, University of Oulu]. OuluREPO. https://oulurepo.oulu.fi/handle/10024/36535

Ishtiaq, J., & Haque, Sk T. M. (2016). Knowledge generation through joint research: What can North and South learn from each other? In T. Halvorsen & J. Nossum (Eds.), North–South knowledge networks: Towards equitable collaboration between academics, donors and universities (pp. 239–254). African Minds, UIB Global. http://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/28917

Jokila, S. (2020). Re/configuring national interest in the global field of higher education: International students recruitment policies and practices in Finland and China [Doctoral dissertation, University of Turku]. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-29-8294-3

Jones, E., & de Wit, H. (2021). The globalization of internationalization? In D. N. Cohn & H. E. Kahn (Eds.), International education at the crossroads (pp. 35–48). Well House Books. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1ghv48c.10

Kálmán, O., Horváth, L., Kardos, D., Kozma, B., Feyisa, M. B., & Rónay, Z. (2022). Review of benefits and challenges of co‐supervision in doctoral education. European Journal of Education, 57(3), 452–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12518

Kannisto, E., Parhiala, J., & Pullinen, H. (2023). Suomen korkeakoulut 2023 raportti. Finnish Institute for Educational Research.

Kim, D., Bankart, C. A. S., & Isdell, L. (2011). International doctorates: Trends analysis on their decision to stay in US. Higher Education, 62(2), 141–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-010-9371-1

Knoke, D., & Yang, S. (2020). Social network analysis (3rd ed.). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781506389332

Kumalo, S. H. (2018). Epistemic justice through ontological reclamation in pedagogy: Detailing mutual (in)fallibility using inseparable categories. Journal of Education, 72. https://doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i72a01

Löfström, E., & Pyhältö, K. (2021). How research on ethics in doctoral supervision can inform doctoral education policy. In A. Lee & R. Bongaardt (Eds.), The future of doctoral research: Challenges and opportunities (pp. 295–306). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003015383

Maringe, F. (2022). Internationalisation in increasingly decolonising Global South university sectors: A prospective view of opportunities and challenges. In L. Cremonini, J. Taylor, & K. M. Joshi (Eds.), Reconfiguring national, institutional and human strategies for the 21st century (Vol. 9, pp. 249–267). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-05106-7_12

Ministry of Education and Culture of Finland. (n.d.). Internationalisation programme and global networks. Ministry of Education and Culture of Finland. Retrieved June 27, 2024, from https://okm.fi/en/internationalisation-programme-and-global-networks

Ministry of Education and Culture of Finland. (2022). Vision for strengthening the international dimension of Finnish higher education and research by 2035. Ministry of Education and Culture of Finland. https://okm.fi/en/vision-for-the-international-dimension-2035

Nerad, M. (2020). Governmental innovation policies, globalisation, and change in doctoral education worldwide: Are doctoral programmes converging? Trends and tensions. In S. Cardoso, O. Tavares, C. Sin, & T. Carvalho (Eds.), Structural and institutional transformations in doctoral education (pp. 43–84). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-38046-5_3

Newman, M. E. J. (2006). Modularity and community structure in networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(23), 8577–8582. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0601602103

Peura, M. (2022). A journey towards and past doctoral studies abroad: Identity-trajectories of Finnish doctoral students in Britain [Doctoral dissertation, University of Turku]. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-29-8840-2

Pfeffer, J. (2017). Visualization of Political Networks. In J. N. Victor, A. H. Montgomery, & M. Lubell (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Networks (Vol. 1, pp. 277-300). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190228217.013.13

Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. SAGE.

Shen, W., Wang, C., & Jin, W. (2016). International mobility of PhD students since the 1990s and its effect on China: A cross-national analysis. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 38(3), 333–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2016.1174420

Smith, E. (2008). Pitfalls and promises: The use of secondary data analysis in educational research. British Journal of Educational Studies, 56(3), 323–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8527.2008.00405.x

Stein, S., & De Andreotti, V. O. (2016). Cash, competition, or charity: International students and the global imaginary. Higher Education, 72(2), 225–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9949-8

Taylor, B. J., & Cantwell, B. (2015). Global Competition, US research universities, and international doctoral education: Growth and consolidation of an organizational field. Research in Higher Education, 56(5), 411–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-014-9355-6

Teferra, D. (2008). The international dimension of higher education in Africa: Status, challenges, and prospects. In D. Teferra & J. Knight (Eds.), Higher education in Africa: The international dimension (pp. 44–79). The Boston Center for International Higher Education and the Association of African Universities.

Teferra, D. (2016). African flagship universities: Their neglected contributions. Higher Education, 72(1), 79–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9939-x

Times higher education world university rankings. (2023). Times Higher Education (THE). https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings

Trahar, S., Juntrasook, A., Burford, J., Von Kotze, A., & Wildemeersch, D. (2019). Hovering on the periphery? ‘Decolonising’ writing for academic journals. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 49(1), 149–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2018.1545817

UNESCO. (2009). 2009 world conference on higher education: The new dynamics of higher education and research for societal change and development (Programme and Meeting Document No. ED.2009/CONF.402/2). UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000183277

UNESCO & African Union. (2023). Education in Africa: Placing equity at the heart of policy; continental report [Continental report]. UNESCO Multisectoral Regional Office for West Africa, African Union Commission Department of Education Science Technology and Innovation. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000384479

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2022). Higher education figures at a glance. https://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/f_unesco1015_brochure_web_en.pdf

University of Helsinki. (n.d.). Instructions for the examiners of doctoral dissertations. Retrieved June 27, 2024, from https://www.helsinki.fi/en/faculty-arts/research/doctoral-education/instructions-examiners-doctoral-dissertations

University of Helsinki. (2021). Focus Africa. https://www.helsinki.fi/en/innovations-and-cooperation/international-cooperation/global-impact/focus-africa

Unterhalter, E., & Howell, C. (2021). Unaligned connections or enlarging engagements? Tertiary education in developing countries and the implementation of the SDGs. Higher Education, 81(1), 9–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00651-x

Välimaa, J., Fonteyn, K. A., Garam, I., van den Heuvel, E., Linza, C., Söderqvist, M., Wolff, J. U., Kolhinen, J., & Finnish Higher Education Evaluation Council. (2013). An evaluation of international degree programmes in Finland. Finnish Higher Education Evaluation Council.

Välimaa, J., & Weimer, L. (2014). The trends of internationalization in Finnish higher education. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 60(5), 696-709. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:14678

Woldegiorgis, E. T. (2023). Changes and continuity in the roles and functions of higher education in Sub-Saharan Africa. In E. T. Woldegiorgis, S. Motala, & P. Nyoni, Creating the New African University (Vol. 16, pp. 40–66). BRILL. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004677432

Woldegiorgis, E. T., & Scherer, C. (2019). Challenges and prospects for higher education partnership in Africa: Concluding remarks. In E. T. Woldegiorgis & C. Scherer (Eds.), Partnership in higher education (Vol. 4, pp. 203–211). BRILL. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004411876_011

World Bank. (2022, June 23). 70% of 10-year-olds now in learning poverty, unable to read and understand a simple text [Text/HTML]. World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/06/23/70-of-10-year-olds-now-in-learning-poverty-unable-to-read-and-understand-a-simple-text