Vol 9, No 1 (2025)

https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.6002

Article

Immigrant parents’ experiences and perspectives on the early childhood education stages in Nordic contexts: A qualitative review and meta-synthesis

Samah M. Migdad

University of Bergen

Email: samah.migdad@uib.no

Kjersti Lea

University of Bergen

Email: kjersti.lea@uib.no

Martin M. Sjøen

University of Bergen

Email: martin.sjoen@uib.no

Abstract

To explore the state of research on immigrant parents’ experiences in early childhood education (ECE) stages, we conducted a literature review through a qualitative meta-synthesis of 22 studies. Guided by sociocultural theory, which emphasizes the co-construction of meaning and the interplay between individual agency and social context, the synthesis highlights both the barriers immigrant parents face and opportunities for enhancing inclusion and support within Nordic ECE contexts. While the articles acknowledge these challenges, they also found that some parents increasingly appreciate Nordic ECE values and practices over time. Communication emerges as a central theme in the reviewed literature; it deeply impacts the integration process of immigrant parents in Nordic ECE systems. Synthesized findings across the studies highlight communication as a key factor shaping parents’ experiences within the categories of “initial experiences and adaptation,” “parental concerns,” and “cultural and social integration.” The review reveals a predominance of host-country researchers, the majority being female, with minority groups underrepresented, which could potentially lead to biases. Despite methodological limitations that impact the understanding of immigrant parents' experiences, the studies offer valuable insights into the parents’ reported experiences and provide a foundation for improving inclusivity and understanding in Nordic ECE.

Keywords: Immigrant parents, early childhood education (ECE), Nordic countries, qualitative meta-synthesis analysis

Introduction

Understanding immigrant parents' perspectives on their children’s education is vital for advancing research, policy, and practice in the field of early childhood education (ECE). In recent years, this area has gained increased attention internationally (Fleer, 2006; Olson & Hyson, 2005) and within the Nordic countries (Lastikka & Lipponen, 2016; Lunneblad & Johansson, 2012). In line with advancements in research, scholars have constructed comprehensive knowledge that may enhance our understanding of multicultural education (Lunneblad & Johansson, 2012; Rissanen, 2020), guide the development of inclusive policies (Bendixsen & Danielsen, 2020; Bønnhoff, 2020), and provide a base for improving educational practices and parent engagement in culturally diverse settings (Garvis, 2020; Sadownik & Ndijuye, 2023). This knowledge may promote the creation of more inclusive pedagogical environments (Gunnþórsdóttir et al., 2019; Nergaard, 2009) and thus ultimately benefit children in ECE.

Research consistently highlights the importance of incorporating parents' views into ECE practices. However, for immigrant families, the transition into a new community and ECE system can be challenging due to cultural and language differences, which often impact their understanding of and engagement with the educational process (Johannessen et al., 2013; Singh & Zhang, 2018). The child-centered approach of Nordic ECE systems focus on children’s desires and curiosity for learning, and is committed to multicultural inclusion, intended to create a supportive framework for all children (Lastikka & Lipponen, 2016; Ślusarczyk & Pustułka, 2016). Still, as research suggests, the success of this pedagogical approach largely depends on how well the ECE systems integrate and respond to parents’ diverse cultural perspectives (Fleer, 2006; Sønsthagen, 2021). Moreover, a contributing factor to minority parents' perspectives on parental involvement is their experiences with and expectations of teacher-parent communication (Lund, 2024; Sadownik & Ndijuye, 2023; Tvinnereim & Bergset, 2023).

This qualitative meta-synthesis represents an interpretative analysis (Chenail, 2009) that combines findings from multiple qualitative studies to explore how immigrant parents in Nordic countries perceive and engage with early childhood education. As Chenail (2009) notes, meta-synthesis involves generating new interpretations and insights by synthesizing qualitative research, with the goal of deepening understanding through an interpretative lens. To achieve these aims we asked: What does research report on how immigrant parents in the Nordic countries perceive and engage with early childhood education?

The review comprises 22 empirical studies with participants from diverse countries, including Russia, Estonia, Iraq, Somalia, Thailand, Spain, and Poland. While providing new insights into research on immigrant parents’ experiences, the review is limited by the scarcity of available literature.

All the reviewed articles examine conditions in the Nordic countries and, since they are qualitative small-scale studies, do not claim generalizability. Our review also recognizes that the findings are specific to the Nordic region and shaped by this region’s unique features. However, by synthesizing the studies, we identify recurring patterns and shared themes that provide broader insights into immigrant parents’ experiences with ECE across the Nordic countries. The geographical focus offers an opportunity to study the intersection of multiculturalism, integration policies, and social equality in a region known for its progressive welfare systems and educational frameworks (Bubikova-Moan, 2017; Bendixsen & Danielsen, 2020; Chajed, 2022). Thus, concentrating on the Nordic context not only enriches the broader discourse on ECE but also informs practices and policies that promote social inclusion and educational success for diverse populations (Nergaard, 2009).

To frame the review, we utilize a sociocultural perspective on communication, which emphasizes the construction of shared meanings through social interaction (Yamamoto et al., 2022). This perspective serves as the lens through which we examine the experiences of immigrant parents within Nordic ECE systems, highlighting the strategies and motivations they report that they use to balance their cultural dispositions when they encounter new social and educational practices. Parents are considered intentional actors who develop goals and strategies to help their children (Major, 2023). While researchers have interpreted their experiences, sociocultural perspectives guide us in reinterpreting these findings. This perspective allows us to consider how parents' cultural model, which may not match their new context, is likely to be challenged and negotiated over time (Yamamoto et al., 2022, p. 268).

In the following section we elucidate key concepts in the research. Following this, we describe our research methodology and theoretical perspective before we present and discuss the findings from the analysis. Lastly, key findings are summarized and concluded.

Key concepts

Early childhood education (ECE)

In this paper, the term early childhood education (ECE) is used to refer to the stages for ages 1-3, 4-5, and 6-8. ECEC denotes an educational progression spanning from preschool class to compulsory school. This aligns with Moss’s perspectives (2013) who emphasizes the interconnectedness of these educational stages and presents them as a continuum that spans from pre-school through compulsory schooling. Early childhood education could be viewed as a seamless progression, highlighting the importance of maintaining developmental continuity as children transit from kindergarten to primary school (Moss, 2013).

In the Nordic countries, a continuum approach is often formalized through national curricula that emphasize the importance of pedagogical coherence between kindergarten and the early years of primary school. The Nordic region is characterized by a strong welfare system in which the state takes extensive responsibility regarding children and families (Handulle & Vassenden, 2021). The formalized role of ECE includes statutory right to parental involvement and to impact what happens in kindergartens and school (Lund, 2024). This approach aims to minimize disruptions in learning and provide children with a supportive, holistic educational environment.

Immigrant

In this

paper, immigrant refers to an individual who has relocated from one

country to another and is making a life for him- or herself in a new cultural

and educational context. Scholars apply this term differently based on their

specific focus, and some prefer alternative terms. For instance, Bønnhoff

(2020) refers to mothers from less digitalized societies; Lastikka and Lipponen

(2016) write about diversity within foreign-born populations, and Nergaard

(2009) specifically identifies first-generation from non-Western countries.

Others, like Matthiesen (2015), use the more conventional terms immigrant

and refugee. We use the word immigrant parents as a collective term for

parents who bring up their children in a country different from their place of

origin. When called for, we use more precise descriptions of the parent's

origins.

While we recognize that immigrant is a broad term with epistemological and axiological implications, and thus acknowledge the term’s limitations and the existence of alternative terms in the literature, we also see that immigrant nevertheless remains the most common term used in research and therefore find it useful for encompassing a wide range of migration backgrounds and experiences.

Methodology and theoretical perspective

Meta-synthesis analysis

Meta-synthesis is a methodological approach that combines findings from multiple qualitative studies to generate new interpretations and insights, beyond those offered by the individual studies (Chenail, 2009). The method was termed qualitative meta-synthesis by Chenail (2009). Unlike meta-analysis, which focuses on numbers and statistics to summarize the results of independent studies, meta-synthesis focuses on interpretative analysis, aiming to create a deeper understanding of complex phenomena (Chenail, 2009). According to Lachal et al. (2017), meta-synthesis provides a systematic and flexible approach to data analysis, balancing methodological rigor with the researcher’s active interpretative role in shaping the final work.

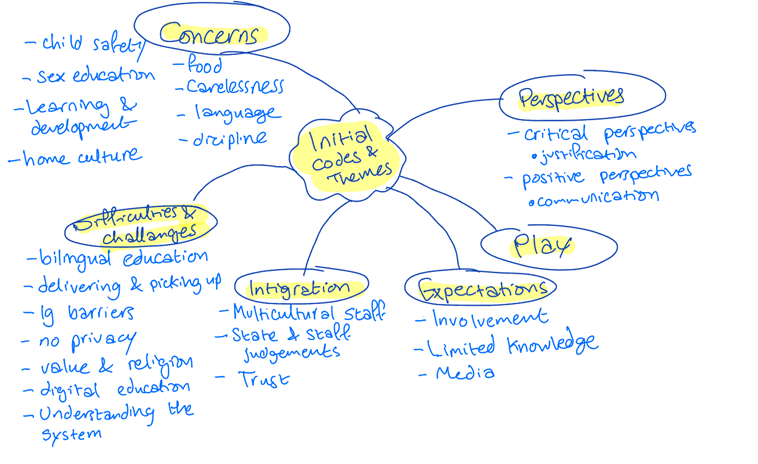

In this meta-synthesis, findings from 22 qualitative studies were analyzed inductively to explore immigrant parents' experiences with early childhood education (ECE) in Nordic contexts. Using NVivo software, initial coding identified recurring patterns, which were grouped into themes such as 'initial experiences and adaptation', 'parental concerns', and 'cultural and social integration'. The analysis involved repeated reading, coding, and refinement of themes. Both explicit experiences (semantic features) and underlying meanings (latent features) were examined to capture the nuanced and multifaceted nature of parents’ perspectives.

Figure 1. Initial codes and themes

Theoretical perspectives

Meta-synthesis aligns with sociocultural theory, which emphasizes the critical co-construction of meaning and the interdependence between individual agency and social context. Theory is always created for someone and for a particular purpose, and reflexive research acknowledges that knowledge is intimately connected to power. Hence, all attempts to explain the social world relate to the motivation and background of the creator of that knowledge. Sociocultural perspectives offer a valuable framework for understanding communication processes within early childhood education (ECE) and the ways in which these processes influence inclusion and exclusion between majority and minority groups in society (Yamamoto et al., 2022). Thus, sociocultural theory can serve as a tool for critically analyzing the naturalized worldview and helping to transform it.

More specifically, in the context of immigrant parents' experiences in Nordic ECE settings, sociocultural theory illuminates how parents navigate and negotiate their roles in response to their sociocultural environment. For instance, themes such as “initial experiences and adaptation” and “cultural and social integration” reflect how immigrant parents reshape their expectations and strategies in alignment with or in contrast to hegemonic Nordic educational practices. Furthermore, sociocultural theory can shed light on how Nordic ECE practices interact with the agency and capital of immigrant parents. While research on the influence of sociocultural contexts on parental involvement remains limited (Yamamoto et al., 2022), previous literature demonstrates that differences between immigrant parents' sociocultural expectations, shaped by differing educational traditions, and the pedagogical approaches of Nordic ECE can lead to misunderstandings and reduced participation (Lenes et al., 2020).

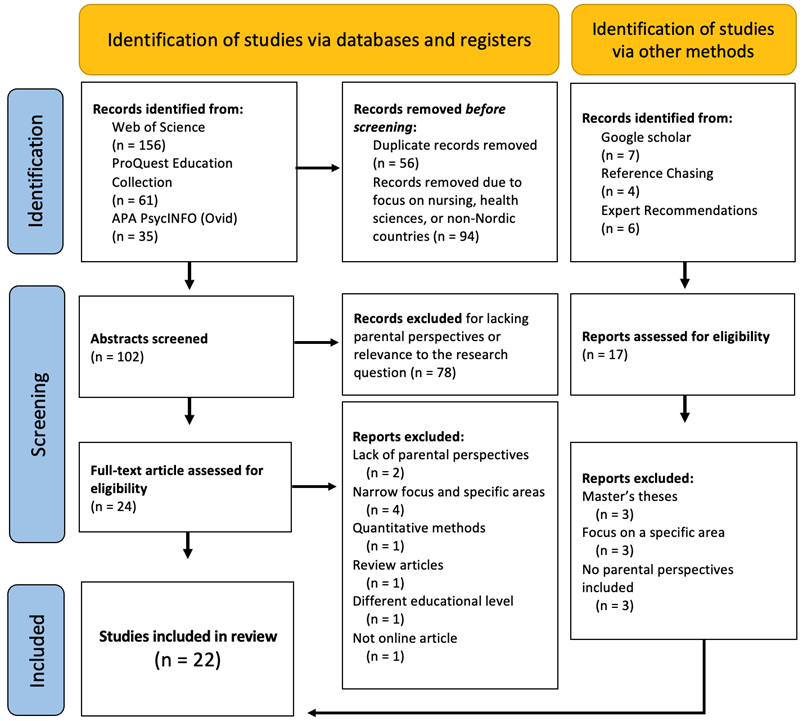

Search strategy and thematic focus

To identify relevant studies for the synthesized review, we conducted a systematic search across several databases. The search was performed by the first author and was conducted from September 6, 2023, to April 5, 2024. The search was guided by predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, focusing on qualitative research related to immigrant parents in Nordic early childhood education settings. We accessed the following databases: Web of Science: 156 records; ProQuest Education Collection: 61 records; and APA PsycINFO (Ovid): 35 records. Additionally, we conducted supplementary searches using Google Scholar and reference chasing, identifying 11 additional records. After the initial search period, and following the cutoff date of April 5, 2024, we received 6 more articles through expert recommendations. It should be noted that search engines and databases may not capture all relevant literature, as some studies are not indexed or published through these platforms, potentially leading to the exclusion of relevant studies. Additionally, relevant studies may have different keywords from those we chose for our search and consequently not been included in our selection.

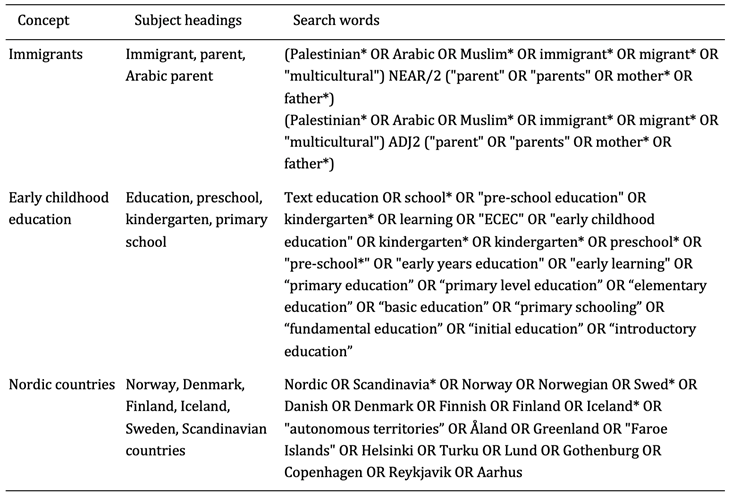

The selection process was documented using the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 2) to ensure transparency and rigor. Table 1 outlines the specific search terms used across the databases.

Table 1. Search items

The original intent of the literature review was to focus specifically on Arabic-speaking parents in Nordic ECE. However, due to scarcity in empirical research, the search strategy and thematic focus was expanded to include immigrant parents in a wider sense.

During the review, communication emerged as a central theme in the literature, impacting the integration process of immigrant parents in Nordic ECE systems. This theme was identified by each author individually through the synthesis of findings across the included studies and is treated as a primary concept in our theoretical framework.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To identify eligible studies, we focused on:

· Publication type: Online and accessible peer-reviewed articles, research reports and doctoral dissertations

· Language: Publications in English or any Nordic national language (Norwegian, Danish, Swedish, Finnish, Icelandic)

· Method: Studies must report empirical data from qualitative methods, such as interviews, focus groups, open-ended surveys, and fieldwork as shown in Figure 3. These methods should include direct quotations or transcripts reflecting immigrant parents’ experiences and perceptions regarding their children's early education. Studies without such direct input were excluded

· Publication year: No restrictions are applied to the publication year, allowing for a thorough examination of literature over time

· Geographical delimitation: Studies must focus on the Nordic countries (Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Iceland)[1]

Studies not meeting these criteria, for example research focusing on child welfare services, health care and social work, were excluded to maintain focus on immigrant parents' experiences from and perspectives on Nordic early childhood education.

Figure 2. PRISMA flow diagram

Data extraction and analysis

To facilitate a comprehensive analysis and synthesis of the studies included, we systematically extracted data using a detailed form to ensure consistency and accuracy. Table 2, located in the appendix, presents a review matrix with key characteristics of each study, including the topic, author(s) and year of publication, study location, research purpose, research perspective, stated key words, and key findings. In some studies, no main themes were explicitly outlined. As a result, themes had to be derived from the findings.

Quality assessment

To ensure the quality of the meta-synthesis, we prioritized transparency and implemented several quality assessment measures. Following PRISMA guidelines, we systematically documented the review process, including search strategies and study selection. With the help of an academic librarian, we refined search terms across databases. The NVivo software facilitated coding and thematic analysis. We collaborated closely, integrating feedback and expertise, while regular meetings and thorough documentation ensured accuracy. Each study was independently reviewed by the three authors, and findings were cross-checked to minimize bias and enhance the reliability of our conclusions.

A reflexive approach to a literature review requires thoughtful engagement with the synthesis, inclusion, exclusion and analysis of relevant literature (Jamieson et al., 2023). In our review, we have provided a transparent research design, outlining the criteria for inclusion and exclusion, and producing a clear chain of synthesized evidence with a clear audit trail for readers to follow. Moreover, unlike naturally occurring data, synthesized evidence exists independently of our review and is publicly available for anyone to scrutinize.

Findings and analysis

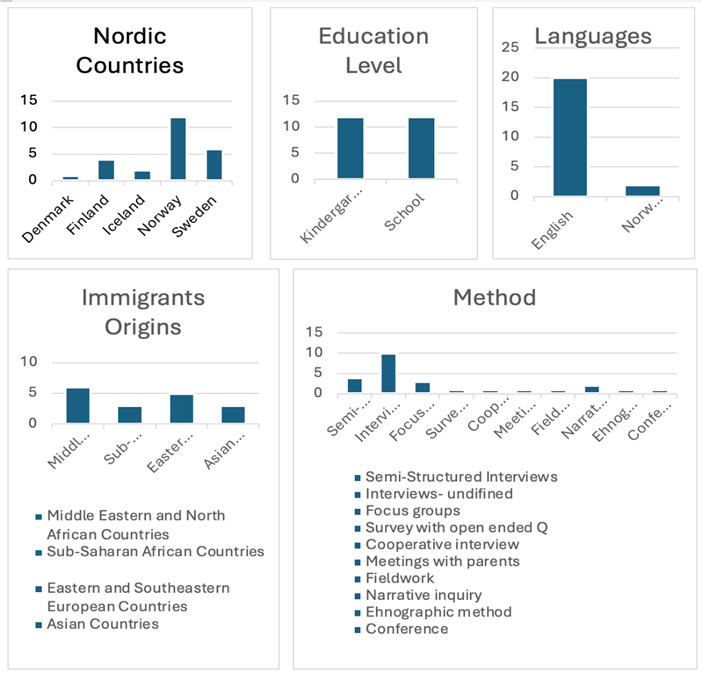

Detailed analysis of study components

To understand the reviewed articles comprehensively, we analyzed key components such as language, research country, method, theoretical frameworks, and overall research context. Our analysis aims to uncover factors influencing research outcomes. The following diagrams summarize essential elements including language, study location, method, education level, and immigrants' origin.

|

Figure 3. Essential elements from the reviewed literature |

|

Theoretical perspectives and contextual variations

The reviewed studies are focused on immigrant parents' engagement with early childhood education and their cultural and social interactions within these settings. The studies employ diverse theoretical frameworks, often situated within critical theoretical paradigms, reflecting the varied approaches authors take in researching immigrant experiences and perspectives on ECE. The theoretical perspective influences the findings and interpretations of the studies. Sociocultural theories are applied in works by Nergaard (2009), Matthiesen (2015), Lastikka and Lipponen (2016), Sadownik and Ndijuye (2023) and Tvinnereim and Bergset (2023). Sociological perspectives are evident in Osman and Månsson (2015) and Matthiesen (2015). Postcolonial theory is found in Lunneblad and Johansson (2012). Many studies overlap in theoretical categorizations, with some referencing theories implicitly or blending multiple frameworks. Studies that explicitly state their theoretical perspectives, such as developmental-ecological theory (Garvis, 2020) and critical theory (Herrero-Arias et al., 2020), offer a structured approach to examining immigrant experiences.

Researcher and participant dynamics

The analysis reveals a dominance of female researchers, many of whom belong to the majority population in Nordic countries. This may have influenced the research process and outcomes, as researchers from the majority population might have different perspectives on immigrant experiences than those of immigrant researchers. Additionally, the asymmetry in the researcher-participant relationship (Ågotnes et al., 2019) may be amplified when the already stronger party in the relationship also belongs to a dominating group (the majority population) while the weaker party belongs to a minority group. Moreover, data generated from interviews in most of the studies is primarily provided by female participants, often mothers, which may lead to underrepresentation of fathers’ perspectives. Nevertheless, the findings are generally referred to as parents’ experiences and perspectives without discussing possible differences between mothers’ and fathers’ views.

Pedagogical themes

In our qualitative meta-synthesis, we analyzed and synthesized qualitative findings, coding and organizing themes according to our research question: What does research report on how immigrant parents in the Nordic countries perceive and engage with early childhood education? The three main themes that emerged from the analysis are 1) initial experiences and adaptation, 2) parental concerns, and 3) cultural and social integration. Additionally, communication appeared as a fundamental element that influences all three themes. This highlights the practical ways in which communication shapes the experiences of immigrant parents in Nordic ECE contexts.

Given the diverse contexts and methodologies of the reviewed studies, we have exercised caution in interpreting these themes, carefully considering the potential biases in the existing literature. While the themes are presented as key areas of focus, we recognize that immigrant parents' experiences vary across different Nordic countries, which may affect how these themes are experienced or understood in each context.

Theme one: Initial experiences and adaptation

Navigating the

unknown

According to

the reviewed research, navigating new experiences and aligning expectations

within early childhood education (ECE) settings can present significant

challenges for immigrant parents, primarily due to unfamiliarity with the

system’s practices, expectations, and cultural norms (Garvis, 2020; Van Wees et

al., 2021). Research by Gunnþórsdóttir et al. (2019) and Sadownik and Ndijuye

(2023) reveals that many immigrant parents report that they struggle to adapt

to new cultural norms and practices, which differ significantly from those in

their home countries. Lund (2022; 2024), in her research on ECE partnership in

Norway, writes about parents from the Middle East and East Africa who face

difficulties because of their unfamiliarity with the Norwegian language, norms,

and the kindergarten norms. The initial engagement can be particularly

stressful, as highlighted by Tvinnereim and Bergset, who illustrate this point

by citing a mother from Latin America, "Why should children sleep outside? It's so

cold! They must be freezing. Norwegians are crazy!” (2023, p. 10 [authors’

translation]). Similar concerns about subzero outdoor sleeping practices are

noted by Herrero-Arias et al. (2020) and Sadownik and Ndijuye (2023) who link

such shocks to cultural adaptation difficulties. Such anxiety is reportedly

often increased by what parents perceive as insufficient pre-kindergarten

information (Tvinnereim & Bergset, 2023).

Expectations of parental involvement in education represent a similar culturally conditioned challenge. Studies by Bønnhoff (2020) and Bendixsen and Danielsen (2020) reveal that many parents struggle with understanding and meeting ECE expectations due to language barriers and differing educational and cultural backgrounds. Bendixsen and Danielsen (2020) refer to a parent from Rwanda who described, “The parents here, especially migrants, have to follow a child to school [...] But where I come from, if we are neighbors, I can collect your children from school, tomorrow you collect him”, suggesting that migrant parents are navigating an uncharted terrain in Nordic ECE and face many difficulties on their way. In line with this, Herrero-Arias et al. (2020) highlight that parents often express a need for more information and support to better navigate the educational landscape.

Expectations of involvement

Researchers

identify a gap between the expectations of ECE institutions and those of

migrant families. Bendixsen and Danielsen (2020) claim that Nordic schools tend

to emphasize individual responsibility and self-discipline, which may not align

with parents’ understanding or capabilities due to language barriers and

unfamiliarity with the system. Similarly, based on an interview with a Kurdish

father, Lund (2024) writes about how immigrant parents feel they must perform

“Norwegianness” when they encounter ECE staff, and Lunneblad and Johansson

(2012, p. 712) quote a father who reveals that “Honestly, it feels like my

power as a parent disappeared when I came to Sweden. The way we educate our

children in my country doesn’t work here”. These sentiments highlight how

differing cultural values and educational practices

can contribute to challenges in communication and involvement.

Lund (2022) refers comments from Bashar, a Syrian father, who compares his stricter approach to Norwegian parents, whom he views as lenient and indulgent. Mustafa adds that immigrant parents focus more on discipline, while Norwegian parents are less strict (p. 204). Lund (2022) argues that these views reflect a cultural clash, with immigrant parents emphasizing authority and structure, while Norwegian parents prioritize autonomy. This cultural clash makes the communication gap between parents and ECE staff bigger, contributing to feelings of isolation and confusion for immigrant families, as emphasized by Lunneblad and Johansson (2012) and Lastikka and Lipponen (2016). Lund (2022) suggests that such differences can lead to misunderstandings in early childhood education settings, highlighting the need for more dialogue and cultural sensitivity to foster inclusivity.

Osman and Månsson (2015) and Sadownik (2022) stress the importance of clear, culturally responsive explanations of pedagogical practices, noting that misunderstandings about practices like outdoor sleeping can lead to frustration. The lack of understanding is not solely due to parents' insufficient knowledge but also reflects a broader issue of communication problems in some Nordic ECE, where staff may not always have the resources, training, or time to communicate with immigrant families (Lund, 2024).

Despite the challenges many parents face, Lastikka and Lipponen (2016) and Sadownik and Ndijuye (2023) note that there also are many parents who report satisfaction with the communication and interaction between daycare personnel and families. For example, Sadownik and Ndijuye (2023) found that parents valued daily updates on their children’s activities and described the staff as attentive and responsive to their concerns. Lastikka and Lipponen (2016) report that while parents appreciated the clarity of communication, some desired more detailed information about their children's learning and development.

Theme two: Parental concern

Language development

The reviewed

research shows that immigrant parents often struggle to support their child’s

development in both their mother tongue and the host country’s language.

Maintaining the mother tongue is a key concern for many parents. They fear that

an emphasis on learning the host language might lead to a loss of their native

language, which is crucial for preserving cultural identity and family

connections. As one mother stated, "For now, I am happy that I can give

her the gift of her mother tongue language, so she is able to communicate in

our family and with relatives" (Garvis, 2020, p. 395). Lastikka and

Lipponen (2016) underscore that while immigrant parents support bilingual

education, they are concerned about their children's ability to maintain their

native language amidst learning the new language.

At the same time, the research reports that parents recognize the importance of proficiency in the host country's language for social integration and academic success. Bendixsen and Danielsen (2020) highlight parents' fears that their children might struggle with the host language and their concerns that a multilingual school environment may hinder their children's ability to learn the host country’s language. On this topic, Sadownik and Ndijuye (2023, p. 8) mentioned one parent stating, “What I really don’t want is for my child to struggle with the Norwegian language like I do”. Similarly, Nergaard (2009) discusses the challenges parents find that children face when language models speak with a heavy accent, complicating language acquisition.

Some of the studies we reviewed observe that language barriers also impact parents’ involvement in their children's education. Bendixsen and Danielsen (2020) note that some parents felt excluded from participating in their children's schooling due to their own limited language competence, and Osman and Månsson (2015) describe a parent who felt her Swedish language skills were too weak to assist her children with homework. Lastikka and Lipponen (2016) emphasize that such language difficulties can significantly hinder family involvement, which is critical for children's educational success.

Childcare quality

Parents often

express concerns about safety and supervision in ECE settings. For instance,

Garvis (2020) discusses how what she terms “skilled immigrant mothers” worry

about potential physical risks in kindergartens, such as unsafe play equipment

and insufficient supervision, which she believes could lead to injuries. The

mothers in this study also highlight issues such as the presence of unqualified

staff and high turnover rates, which exacerbate their fears about their

children's safety. For example, one mother in the study says, “I have concerns

about the safety of my children when the person does not have qualifications. I

would not trust an unqualified doctor, so why should I trust an unqualified

teacher?" (Garvis, 2020, p. 393).

Herrero-Arias et al. (2020), Sadownik and Ndijuye (2023) and Lund (2024) document similar concerns about ECE practices that vary from those in the interviewees’ home countries. Sadownik and Ndijuye (2023) mention anxieties over Norwegian practices, such as practitioners encouraging children who fall to ‘get up again’, whereas in some cultures, it is more common to show empathy for the child's injury. The study quotes a parent who says, "I already gave up the hope that he would learn something here, but please at least take care of him here!" (p. 7). Herrero-Arias et al. (2020) describe parental unease with practices perceived as unsafe, such as one-year-old children playing outdoors in all weathers, playing on hills with stones or mud and handling sharp tools like axes and knives. Yet, according to this study, over time many parents come to appreciate the Nordic ECE practices as they observe their children's increasing independence. A quote from one of the parents illustrates this point:

[X]: I remember how shocked I got when I started my job in the kindergarten and saw 4-year-old children going on an excursion far away, and they took foldable knives. [Y]: They give small axes to 5-year-old children [X]: I thought, “I’m going to get a heart attack”, the knives were so sharpened. [Y]: There’s always somebody supervising but nobody approaches the children, “Don’t take this! Be careful!” [X]: Yes, because for them what matters is that the child learns and has fun, it doesn’t matter if the child gets dirty, a bit injured (Herrero-Arias et al., 2020, p. 413).

Parents also express concerns about the quality of food in ECE institutions. Sadownik (2022) notes parental shock over the “almost daily serving of hot dogs” (p. 10), which they view as compromising children's health. However, parents appreciate efforts to accommodate religious dietary restrictions and create pleasant, stress-free meal experiences. Thus, concerns about food quality are balanced with appreciation for inclusive and accommodating practices (Sadownik & Ndijuye, 2023).

Beyond safety, different studies underscore that clear communication between parents and ECE personnel is crucial for building trust, which is regarded essential for childcare quality. Lastikka and Lipponen (2016) emphasize that positive interaction with ECE staff helps ease parental concerns., and Lund (2022) highlights the importance of communication and trust in the relationship between refugee parents and kindergarten staff. High staff turnover and unqualified personnel in kindergartens can erode this trust (Garvis, 2020).

Learning and development

Some research

reports that parents express concern about the

educational approach in Nordic ECE, particularly the balance between play and

structured learning. For example, Gunnþórsdóttir et al. (2019) find that

foreign-born parents often view the limited homework and the focus on play in

Icelandic primary schools as inconsistent with their expectations for academic

rigor. One parent who took part in this study explains:

She doesn’t learn anything if she doesn’t have to try. I only want to let her try, but they [the teachers] don’t want to because they don’t want to make it hard for her. I think if there would be a little bit more pressure, she would learn more (Gunnþórsdóttir et al., 2019, p. 609-610).

According to this study, some parents supplement their children’s education at home to meet the academic standards in their home countries. For instance, one of the mothers who took part in this study taught her child for an hour or two each day about Poland. Additionally, at least four European parents in the study perceive Iceland’s educational standards as roughly “two years behind” those of their home country (Gunnþórsdóttir et al., 2019, p. 613).

Although parents recognize the life skills gained through Nordic approaches, they often find it challenging to align these benefits with their own expectations for academic learning. Sadownik and Ndijuye (2023) highlight that some parents, unfamiliar with play as a pedagogical approach in ECE, are skeptical. One father asks, "How is this good?” referring to his belief that he “send[s] them to school to ensure that they learn the necessary skills that they cannot otherwise learn at home" (p. 7). Without clear explanations of the value of play, parents may perceive it as "a limitation of the children’s learning opportunities" (Sadownik & Ndijuye, 2023, p. 7). On the other hand, Ślusarczyk and Pustułka (2016) find that after gaining some insight into Nordic pedagogical practices and the importance of play, some parents begin to appreciate this approach. Parents offered statements like "I realised that here they allow children to grow up" (p. 58), and "I like that here they […] have breaks for playing, […] It is not stressful at all" (p. 59). Similarly, Bubikova-Moan (2017) describes one parent who initially criticized the lack of academic focus but later recognized the joy and growth her child experienced, ultimately acknowledging, "Why at all – worry that it’s supposed to be like this or like that. Basically, he is happy and that’s it" (p. 33). Lastikka and Lipponen (2016) highlight how multicultural environments in Finnish kindergartens support both learning and social development, and Herrero-Arias et al. (2020) find that parents’ initial worries about practices like using knives and axes evolve into an appreciation for the self-sufficiency and independence their children develop.

Theme three: Cultural and social integration

ECE as a gateway to integration

Examining

how the host country’s ECE influences integration, several studies reveal

multifaceted impact on both parents and children. Garvis (2020) and Rissanen

(2020) both address the complexities of cultural integration. Garvis (2020)

highlights that migrant parents often engage with the host culture only after

their children start formal schooling, reflecting challenges in aligning family

and educational practices across cultures. Rissanen (2020) discusses how

Swedish schools often limit negotiation on cultural differences, with parents

being told they could "always choose to send their children to an Islamic

school" (p. 141)[2], which restricts integrating diverse

cultural practices within public education.

In alignment with these findings, Tvinnereim and Bergset argue that trust built through "mutual insight and understanding” (2023, p. 14 [authors’ translation]) is crucial for integration in nursery settings. Sønsthagen (2018) similarly notes that when mothers, who often had limited social networks, expressed trust, this often suggests the start of belonging. Both of these studies highlight trust as essential for fostering belonging and successful integration. Lund (2022) supports this, noting that as refugee parents become familiar with the kindergarten system and its norms, their initial insecurities evolve into confidence, fostering trust in both staff and the organization. Sønsthagen (2018) also highlights the importance of positive, consistent staff-parent interactions, which gradually build personal trust and contribute to parents’ confidence in the kindergarten’s ability to provide a safe and nurturing environment.

Building on the alleged importance of trust, Garvis (2020) and Tvinnereim and Bergset (2023) elaborate on how fear also significantly affects parents. For instance, Garvis (2020, p. 393) describes a mother who lost confidence in the institution. She regarded it as unsafe and untrustworthy because of an “unqualified teacher”, after her friend's child was bitten and the incident allegedly was inadequately addressed. Similarly, Bendixsen and Danielsen (2020) and Tvinnereim and Bergset (2023) highlight parental anxiety over potential child welfare interventions.

Tvinnereim and Bergset (2023) present an African mother who expressed fears about child welfare services, stating, "I was so worried about those who could take our children away. We have to be afraid and on guard!" (p. 12 [authors’ translation]). Bendixsen and Danielsen (2020) reveal similar concerns about state intervention, with some parents perceiving that "the people [working in Child Welfare Service] are manipulating the system and they steal children from migrants and they give them to Norwegian families" (p. 358). As the examples indicate, fear often arises from concerns that interactions in ECE, such as cultural misunderstandings, differing expectations, or perceived "wrong" behavior, could lead to reports to child welfare services, ultimately threatening the security of their family.

Given the complexities of integration, understanding how various factors influence this process in Nordic ECE is crucial. Van Wees et al. (2021) highlight the importance of including language use when communicating with parents of different native languages. In this study, Arabic-speaking staff in Swedish ECE institutions help bridge communication gaps for Arabic-speaking migrant families, thus enhancing their engagement. In a broader context, Matthiesen (2015) and Lastikka and Lipponen (2016) illustrate the role of ECE institutions in fostering cultural understanding. They find that multicultural personnel and inclusive practices contribute significantly to a sense of belonging and safety, allowing parents to preserve their cultural identity while adapting to new norms. Similarly, Matthiesen (2015) explores how migrant parents navigate cultural and systemic challenges, for example when balancing their child's well-being with the demands of the educational system.

Several studies, including those by Gunnþórsdóttir et al. (2019), Bønnhoff (2020), Tvinnereim and Bergset (2023), and Lund (2024), explore the complexities migrant parents encounter in adapting to new educational practices. Bønnhoff (2020) shows that migrant mothers in Norway sometimes adapt their practices to align with local values, reflecting broader efforts to integrate into Norwegian societal norms. As one mother noted, she "changed her practices after migrating, choosing to talk about topics she previously considered taboo" (Bønnhoff, 2020, p. 387). Gunnþórsdóttir et al. (2019) demonstrate that the introduction of new practices, such as swimming lessons, can lead to discomfort and resistance among migrant families, and Tvinnereim and Bergset (2023) call attention to the pressure migrants may feel to conform to local norms. One parent explained his feeling that "We have to respect all Norwegians because we decided to come here, so we have to do as all Norwegians say—otherwise, we can be thrown out" (p. 12 [authors’ translation]).

Balancing cultures: home vs. host country

According to

researchers, navigating cultural differences between home and host countries

presents a complex challenge for migrant families (Bønnhoff, 2020; Garvis, 2020;

Ślusarczyk & Pustułka, 2016). Many parents strive to maintain their

children's cultural identity, rooted in the parents’ country of origin, while

adapting to the norms of their new environment. For instance, Garvis (2020) finds

that some migrant mothers prioritize their child's understanding of their home

culture before introducing new cultural elements from their host country. As

one of the mothers this study stated, "I want my child to understand and

respect this before an additional culture is added" (p. 395). This

sentiment reflects the belief of many migrant parents that their children

should be grounded in their heritage before diving into a new cultural

environment (Garvis, 2020).

Several studies point out that adaptation to the host country’s educational norms can be challenging and stressful, especially when these norms differ significantly from those in the home country, leading to tension and discomfort. For instance, both Bønnhoff (2020) and Van Wees et al. (2021) highlight the difficulties parents encounter when local educational practices in Sweden and Norway, especially on sensitive topics like sex education, conflict with their own beliefs. The authors explain that parents had concerns about the impact these practices have on their children. This created challenges in balancing cultural preservation with the integration of local values. According to Van Wees et al. (2021), "Parents felt that teachers were undermining their beliefs and values" (p. 3).

Sadownik and Ndijuye (2023) note that parents frequently assess the educational standards in their new country against those of their home country, often perceiving inadequacies in the host country's system. This comprises religious education as well. Lastikka and Lipponen (2016) find that while cultural support is appreciated, specific religious practices often go unacknowledged. Ślusarczyk and Pustułka (2016) underscore this issue, noting that while students learn about various religions, parents feel that their children’s specific religious beliefs are not adequately represented. The study quotes a Polish mother who declared, "Students learn about many religions and not one religion that happens to be the one we believe in" (p. 60). Similarly, Rissanen (2020) presents participants’ claim that the emphasis on Protestant Christianity in Finnish and Swedish schools can marginalize other religions, particularly Islam. Furthermore, Matthiesen (2015) demonstrates how religious symbols, such as headscarves, may provoke skepticism, and declares that a more inclusive approach to religious diversity in schools is required.

Discussion and conclusion

The aim of this study was to map out what research reports on how immigrant parents in the Nordic countries perceive and engage with early childhood education (ECE). The findings of the review highlight several key aspects of immigrant parents' experiences, with communication emerging as a central factor in their inclusion, adaptation, and collaboration within Nordic ECE. We analyzed the findings from a sociocultural perspective, which helps understanding of how communication, cultural adaptation and social capital, influence interaction between immigrant parents and ECE providers.

The findings suggest that immigrant parents often encounter cultural differences that challenge their expectations of parental involvement, leading to confusion, anxiety, and a need for culturally sensitive communication from ECE providers to help parents adapt to their new environment. The Nordic emphasis on child independence and informal parental engagement contrasts with the structured or formal approaches that many immigrant parents are used to. Such misalignments can lead to confusion, hesitation, and feelings of isolation among parents (Lenes et al., 2020). From a sociocultural perspective, this tension reflects how immigrant parents actively adjust, negotiate and redefine their roles in their new cultural context (Yamamoto et al., 2022). For instance, some parents assert that they have come to understand and value Nordic ECE ideals, suggesting that cultural adaptation is a gradual process supported by communication and social interaction. However, based on the literature, these adaptive processes do not appear to be conducive between host communities and immigrants, seeing how it is often immigrant parents who adapt to the hegemonic cultural values that make up Nordic ECE practices, rather than the educational context adapting to the changing cultural landscape.

While language barriers and cultural differences present significant challenges for immigrant parents, it should be noted that these issues are not exclusive to this group. Some parents from majority populations may also experience difficulties with trust, communication, and understanding certain ECE practices. For example, they might be uncomfortable with ECE teaching sensitive topics, serving unfamiliar or low-quality food, or providing unusual activities like young children playing with axes. These concerns can arise for any parent unfamiliar with or new to the system, but they also reflect differing values and expectations in general about what is appropriate or beneficial for children. However, as noted by Major (2023), because of variations in social and cultural capital between immigrant parents and parents who belong to the majority population. This makes it harder for immigrant parents to engage fully or express their concerns, highlighting the role of social and cultural capital in shaping their involvement in ECE.

The review suggests that trust-based communication between parents and ECE staff plays a crucial role in bridging gaps in understanding. Sociocultural theory emphasizes the co-construction of meaning through shared interactions (Yamamoto et al., 2022), suggesting that open, empathetic communication can help align expectations and practices between parents and staff. Miscommunication, often arising from cultural differences or lack of shared understanding, can hinder this process.

When ECE providers recognize and value parents' cultural strengths, they create a supportive environment that encourages mutual understanding and collaboration (Yamamoto et al., 2022). Recognizing the strengths of cultural diversity may deepen the discussion of immigrant parents' roles and involvement in ECE by emphasizing the potential benefits of inclusivity, which is considered important for promoting immigrant parents' contributions in ECE. However, while it is often suggested that ECE providers should shape parents' beliefs and involvement practices, we argue that this approach may not align with parents' needs and could unintentionally marginalize their cultural perspectives. A high degree of reflexivity is required to reveal unconscious sociocultural biases and ensure transparency in research design and positionality, which can influence both data collection and inclusivity in ECE practices (Jamieson et al., 2023).

As Tvinnerheim and Bergset (2023) note, building trust through mutual understanding is crucial for creating a supportive environment. Trust-based communication can bridge cultural gaps and enhance parental engagement, promoting a more inclusive ECE experience. However, less attention is given to how the ECE system might adapt to immigrant parents' cultural perspectives, raising questions about the balance between parents adapting to the system and ECE providers adjusting their practices to include immigrant parents (Yamamoto et al., 2022).

The studies we reviewed reveal immigrant parents’ diverse experiences of their interactions with ECE professionals, highlighting both exclusionary and assimilative challenges, as well as opportunities for enhancing inclusivity and support. However, this field of research is characterized by a lack of clear definitions and consistent theoretical frameworks. This absence can lead to unfounded assumptions about a universal understanding of immigrant experiences, which may result in inaccurate or overly generalized conclusions. Researchers may thereby overlook the complexity and diversity of immigrant parents’ challenges. To ensure fair representation and well-grounded interpretations, researchers should explicitly outline their theoretical perspectives.

Our findings moreover indicate an imbalance in the representation of participants in ECE research. While fathers are included in most of the studies, mothers constitute the majority of the participants. Although some studies tend to emphasize mothers' perspectives, they typically use general terms like "parents" or "participants" without distinguishing between the experiences of mothers and fathers. This raises questions about how findings might differ if fathers' perspectives were more prominent or if the differences between male and female parents' viewpoints were directly addressed. Fathers may have distinct views on involvement in ECE, cultural adaptation, or parenting roles that could deepen our understanding of immigrant parents’ experiences.

Additionally, the dominance of female researchers, many of whom belong to the majority population in Nordic countries, can influence research outcomes. Researchers’ cultural and social positions may influence how they interpret and understand participants' accounts. Majority-group researchers may unconsciously study immigrant experiences through their own cultural lens, which could lead to unintended biases and affect the depth of understanding. Reflexivity in research is crucial to ensure that these biases are recognized and carefully considered. Studies (e.g., Jamieson et al., 2023) emphasize the need for a more diverse range of researchers to bridge gaps, address power imbalances, and enrich research.

Overall, the findings highlight that immigrant parents face challenges arising from their position as cultural outsiders within systems designed around majority norms. These challenges are deeply rooted in societal and institutional contexts, rather than in personal or familial factors. A sociocultural perspective provides a critical lens to examine how these dynamics develop, showing how interactions with ECE staff are influenced by and can reshape the broader sociocultural environment. Sociocultural theory underscores the importance of recognizing cultural and social dynamics in parental engagement, paving the way for more inclusive and responsive educational practices and policies. Moreover, this study contributes to sociocultural theory by illustrating how Nordic ECE practices, which often focus on immigrant parents' adaptation, can either reinforce or challenge existing cultural norms, calling for a more flexible approach to parental engagement that supports institutional transformation.

References

Bendixsen, S., & Danielsen, H. (2020). Great expectations: Migrant parents and parent-school cooperation in Norway. Comparative Education, 56(3), 349–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2020.1724486

Bubikova-Moan, J. (2017). Negotiating learning in early childhood: Narratives from migrant homes. Linguistics and Education, 39, 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2017.04.003

Bønnhoff, H. E. D. (2020). Fostering 'digital citizens' in Norway: Experiences of migrant mothers. Families Relationships and Societies, 10(3), 377–393. https://doi.org/10.1332/204674320x16047231238221

Chajed, A. (2022). Trying to make it “feel like home”: The familial curriculum of (re)constructing identities and belonging of immigrant parents living in Finland [Doctoral dissertation]. Teachers College, Columbia University.

Chenail, R. J. (2009). Bringing Method to the Madness: Sandelowski and Barroso’s Handbook for Synthesizing Qualitative Research. The Qualitative Report, 13(4), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2009.2820

Fleer, M. (2006). Troubling Cultural Fault Lines: Some Indigenous Australian Families’ Perspectives on the Landscape of Early Childhood Education. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 13(3), 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327884mca1303_3

Garvis, S. (2020). An Explorative Study of Skilled Immigrant Mothers' Perspectives Toward Swedish Preschools. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 35(3), 389–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2020.1731635

Gunnþórsdóttir, H., Barillé, S., & Meckl, M. (2019). The Education of Students with Immigrant Background in Iceland: Parents' and Teachers' Voices. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 63(4), 605–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2017.1415966

Handulle, A., & Vassenden, A. (2021). ‘'The art of kindergarten drop off’: How young Norwegian-Somali parents perform ethniticy to avoid reports to Child Welfare. European Journal of Social Work, 24(3), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2020.1713053

Herrero-Arias, R., Lee, E., & Hollekim, R. (2020). 'The more you go to the mountains, the better parent you are'. Migrant parents in Norway navigating risk discourses in professional advice on family leisure and outdoor play. Health Risk & Society, 22(7-8), 403–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2020.1856348

Jamieson, M. K., Gisela, G. H., Pownall, M. (2023). Reflexivity in quantitative research: A rationale and beginner's guide. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 17(4), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12735

Johannessen, Ø. L., Odden, G., Ryndyk, O., & Steinnes, A. (2013). Afghans and early childhood education in Norway. A pilot report (SIK-rapport 2013:2). Senter for Interkulturell Kommunikasjon.

Lachal, J., Revah-Levy, A., Orri, M., & Moro, M. R. (2017). Metasynthesis: An original method to synthesize qualitative literature in psychiatry. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00269

Lastikka, A.-L., & Lipponen, L. (2016). Immigrant Parents’ Perspectives on Early Childhood Education and Care Practices in the Finnish Multicultural Context. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 18(3), 75–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18251/ijme.v18i3.1221

Lenes, R., Gonzales, C., Størksen, I., & McClelland, M. (2020). Children’s Self-Regulation in Norway and the United States: The Role of Mother’s Education and Child Gender Across Cultural Contexts. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.566208

Lund, H. H. (2022). «Vi må gjøre som nordmenn, gå på tur og sånn, integrere oss»: Flyktningforeldres erfaringer med barnehagen. Nordic Early Childhood Education Research, 19(3). https://doi.org/10.23865/nbf.v19.385

Lund, H. H. (2024). "We try to give a good life to the children” -- Refugee parents and ECE professionals experiences of the early childhood education partnership in Norway. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1331771

Lunneblad, J., & Johansson, T. (2012). Learning from each other? Multicultural pedagogy, parental education and governance. Race Ethnicity and Education, 15(5), 705–723. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2011.624508

Major, E. (2023). Parent-Teacher Communication from the Perspective of the Educator. Central European Journal of Educational Research, 5(2), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.37441/cejer/2023/5/2/13281

Matthiesen, N. C. L. (2015). Understanding silence: An investigation of the processes of silencing in parent–teacher conferences with Somali diaspora parents in Danish public schools. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 29(3), 320–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2015.1023236

Moss, P. (2013). Early childhood and compulsory education: Reconceptualising the relationship. Routledge.

Nergaard, T. B. (2009). The Day Care Experience of Minority Families in Norway. Child Care in Practice, 15(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575270802504347

Olson, M. & Hyson, M. (2005). NAEYC Explores Parental Perspectives on Early Childhood Education. Young Children, 60(3), 66–68.

Osman, A., & Månsson, N. (2015). "I Go to Teacher Conferences, But I Do Not Understand What the Teacher Is Saying": Somali Parents’ Perception of the Swedish School. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 17(2), 36. https://doi.org/10.18251/ijme.v17i2.1036

Rissanen, I. (2020). Negotiations on Inclusive Citizenship in a Post-secular School: Perspectives of "Cultural Broker" Muslim Parents and Teachers in Finland and Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 64(1), 135–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2018.1514323

Sadownik, A. R. (2022). Narrative Inquiry as an Arena for (Polish) Caregivers’ Retelling and Re-experiencing of Norwegian Kindergarten: A Question of Redefining the Role of Research. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education, 6(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.4503

Sadownik, A. R., & Ndijuye, L. G. (2023). Im/migrant parents' voices as enabling professional learning communities in early childhood education and care. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 13. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293x.2023.2259643

Singh, P., & Zhang, K. C. (2018). Parents’ Perspective on Early Childhood Education in New Zealand: Voices from Pacifika Families. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 43(01), 52–58. https://doi.org/10.23965/AJEC.43.1.06 Ślusarczyk, M., & Pustułka, P. (2016). Norwegian schooling in the eyes of Polish parents: From contestations to embracing the system. Central and Eastern European Migration Review, 5(1), 49–69. https://doi.org/10.17467/ceemr.2016.06

Sønsthagen, A. G. (2018). «Jeg savner barnet mitt». Møter mellom somaliske mødre og barnehagen. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education, 2(1), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.2289

Sønsthagen, A. G. (2021). Leadership and responsibility: A study of early childcare institutions as inclusion arenas for parents with refugee backgrounds [Doctoral dissertation]. University of South-Eastern Norway.

The Swedish National Commission for UNESCO (2021, December 14). Pressmeddelande: Unesco-rapport visar att privata skolor bidrar till klyftor i världens länder. UNESCO. https://unesco.se/pressmeddelande-unesco-rapport-visar-att-privata-skolor-bidrar-till-klyftor-i-varldens-lander/

Tvinnereim, K. R., & Bergset, G. (2023). "Det er veldig forskjellig fra hjemlandet mitt". Migrantforeldres erfaringer med kommunikasjon og samhandling med barnehagepersonalet. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education, 7(3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.5457

van Wees, S. H., Fried, S., & Larsson, E. C. (2021). Arabic speaking migrant parents' perceptions of sex education in Sweden: A qualitative study. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, 28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2021.100596

Yamamoto, Y., Li, J., & Bempechat, J. (2022). Reconceptualizing parental involvement: A sociocultural model explaining Chinese immigrant parents’ school-based and home-based involvement. Educational Psychologist, 57(4), 267–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2022.2094383

Ågotnes, G., Lea, K., & Petersen, K. A. (2019). Reflections on interviews: Official accounts and social asymmetry. Praktiske Grunde: Nordisk tidsskrift for kultur- og samfundsvidenskap, 1-2, 207-219.