Vol 9, No 3 (2025)

https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.6058

Article

TALIS 2018 data indicates that teachers need support for developing skills in Pedagogical Decision Making

Susan Wiksten

AGORA for the study of social justice and equality in education (AGORA), University of Helsinki

Email: susanwiksten@gmail.com

Abstract

From a sociology of education perspective, a concern in teacher education is that teaching practices and expectations to the professional role of teachers often build on assumptions that derive from the social context of instruction. Whereas international comparisons regularly focus on characteristics of individuals or selected segments of the population, such as pre-service teachers or individual teacher education programmes, this article contextualizes socially derived expectations using secondary analysis of survey data for fourteen countries across four continents. A review of publicly available data from the World Bank and the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) was carried out. The secondary analysis consists of a juxtaposition and visualization of descriptive data. Analysis of survey data highlights shared assumptions and expectations across fourteen countries. The data indicates that some teacher attitudes are not a result of characteristics specific to individual teachers or the teacher profession in general but are associated with variation between countries. The article draws theoretically and methodologically on prior Comparative and International Education (CIE) research and proposes that teachers across subject matter specializations and across contexts benefit from the development of Pedagogical Decision-Making skills (PDM). More attention to the development of specific PDM skills is proposed as a means for strengthening teacher resilience.

Keywords: TALIS survey, teacher education, Pedagogical Decision-Making skills, resilience

Introduction

The teaching profession is one of the large professions in terms of numbers of persons employed (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022; OECD, 2022)[1], which in part reflects the important public service that teachers as a professional group contribute to. Teaching is a demanding profession in which the constant interaction with students, when successful, can be a source of professional affirmation, discovery and development. This is unfortunately not the case for all who enter the profession. Instead of finding joy in the challenges to develop as a teacher, many become burnt out from multiple sources of unreasonable expectations and political pressures (García-Arroyo et al., 2019; Pyhältö et al., 2021). Common problems relate to excessive workloads and expectations that teachers manage challenges alone (García-Arroyo et al., 2019; Pyhältö et al., 2012; 2021), as well as expectations that teachers manage student behaviour (Lanas & Brunila, 2019; Lanas et al., 2022). In terms of socio-cultural normative expectations, managing student-, parental- and organizational-expectations comes to some extent naturally from a shared familiar cultural context. However, managing shifting expectations can involve demanding challenges ranging from parental requests to prioritize individual students to political developments in the local community. Shifts in societal power relations impact the expectations that teachers navigate in everyday instruction, just to mention one type of social-context related expectations (Abu El-Haj, 2023; Morrow, 2021).

Teacher education plays a role in supporting teacher resilience. Comparative research on teacher attrition in Europe shows that 70% of teachers who decide to leave the profession do so immediately after the first teaching experience, and those with less education are more likely to leave the profession (Federičová, 2021, pp. 108–109). Teacher turnover is a recognized sign of dysfunctionality in education settings. In some cases, frequent turnover is due to dysfunctional organizational practices such as assigning the least experienced teachers to students who most need support (Placklé et al., 2022). An anecdote which per se does not represent teacher education programmes in general, but nevertheless starkly illustrates challenges with insufficient teacher preparation is provided by the short preparation provided to university graduates in the Teach for America programme. Teach for America is a scheme that has placed university graduates in teaching positions with only a few weeks of teacher education. Teach for America graduates have been observed to engage in teaching on average for less than three years, using the teaching experience primarily as a steppingstone for a career in another field (Darling-Hammond et al., 2005). The development of specific Pedagogical Decision-Making (PDM) skills, as a means for strengthening teacher resilience, is discussed in this article in light of descriptive data from the TALIS teacher survey (OECD, 2019).

From a sociology of education perspective, a concern in teacher education is that teaching practices and expectations to the professional role of teachers often build on assumptions. Education as a field of practice is riddled with something that metaphorically can be referred to as a kind of amnesia, in that practitioners lack familiarity with prior research in education and awareness of the reasons for why certain practices are used. ‘We teach like this because we were taught like this’ is perhaps the weakest argument for a choice of teaching method, and yet it is surprisingly often the response that teacher education students at UCLA proposed in the course on Global Citizenship Education that I taught in 2019 - 2022. This illustrates a disassociation of teachers from decisions on how to teach and how to evaluate student skills. A disassociation that in part has been fueled by standardization in education (Wiksten, 2020). The use of shared references, national examinations and international surveys has diverted attention from the valid professional role of teachers in making day-to-day decisions about teaching in classrooms.

A manifestation of this tendency is reflected in research that articulates teaching practice as an artform, or a question of style or artistry (Anderson-Levitt et al., 2017; Woods & Jeffrey, 2021). Research on the art of teaching recognizes in a symbolic interactionist perspective the complex cultural and context specific circumstances of instruction. This ethnographic branch of teacher education research is helpful for reflecting on e.g. teacher positionality (Cedillo & Bratta, 2019; Tien, 2019). It sheds light on how the cultural context exercises socio-cultural constraints to teacher autonomy (Giddens, 1986), and why teacher students have a strong tendency to mimic teaching practices they have experienced firsthand — rather than make informed decisions on their own.

How teaching practice is affected by macro-societal external pressures

However, when the teacher is presented as an artist, the macro-societal context risks being omitted in analysis. A particular advantage of international comparisons and surveys such as the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) is the perspective that can be gained regarding factors beyond individual teachers, and beyond local sets of socio-culturally derived assumptions (OECD, 2019). Notably, to shed light on macro-societal constraints to teacher autonomy (Giddens, 1986) that pertain to the different circumstances, possibilities and constraints of instruction in terms of how (1) schools are organized (Köhler, 2022; Schanzenbach, 2020); (2) what resources are available; (3) how many lessons teachers are expected to teach per week; (4) the extent to which curriculum implementation is provided as general guidelines or as scripted lessons (Ahmed, 2019; Eisenbach, 2012); (5) how curricula are developed; and (6) how dependent an education system is of private supplementary education (Liu & Bray, 2020; Zhang, 2020). These are examples of some of the enabling and constraining circumstances that are heavily influenced by macro-societal variation and thereby importantly contribute to expectations and external pressures under which teachers work.

The following section contributes context for a further discussion by presenting descriptive data from (1) a survey of teachers and principals in fourteen countries across four continents, and (2) data from the World Bank. A review of publicly available World Bank data and data from the TALIS survey was carried out. Results from the secondary analysis, which consists of a juxtaposition and visualization of descriptive data, are used for highlighting shared assumptions and expectations across fourteen countries. The data analyzed includes self-reported responses from approximately 47985 teachers. The data indicates that some teacher attitudes are not only a result of characteristics specific to individual teachers or the teacher profession in general but are associated with variation between countries, i.e. variation that draws on the societal context rather than differences between individual teachers.

In the second part of the article, data regarding some of the challenges and possibilities for teacher education to address expectations to the role of teachers in mitigating inequity in different macro-societal contexts is discussed. Using a Comparative and International Education (CIE) perspective (Torres et al., 2022) I propose that pedagogical decision-making skills (PDM) represent a constructive means for supporting abilities that teachers need to develop. Specifically, skills needed to withstand what is here identified as expectations that are external to the substantive legitimate expectations to the teaching profession proper — when teachers e.g. are expected to privilege individual students or there is pressure to accommodate for societal changes without support. While managing expectations is a normal part of the day-to-day of instruction, nevertheless, the category identified here as “unreasonable expectations” deriving from the social context including, but not limited to, excessive workload, represent expectations where teachers necessarily negotiate and communicate boundaries in relation to expectations to avoid burnout (Pyhältö et al., 2021).

While recognizing context specific challenges that vary by factors that include geographical location, type of institution, subject matter specialization and socio-cultural context, a specific stance is taken in this article that focuses on the agentic role of teachers (Giddens, 1986) amidst the possibilities, challenges and limitations for the development of the teaching profession. Data-analysis presented in the first part of this article is used for an international comparison that juxtaposes circumstances between fourteen countries on one hand and micro-level understandings of the role of teachers on the other, for mitigating inequity (Kranich, 2005). The circumstances and teacher stances demonstrated by World Bank and OECD data are in the second part of this article used for developing a discussion on the connection between macro-societal context and expectations to the role of teachers in mitigating inequities. Using a Comparative and International Education perspective (Torres et al., 2022), the discussion identifies challenges in education that are relevant across subject matter curricula, to highlight why supporting the development of PDM skills among teachers is central for improving teacher retention, teachers’ ability to discern between reasonable and unreasonable expectations and supporting teacher professional development to meet the challenges of societal changes.

Comparative international data on societal inequity and teacher motivation

International TALIS survey data (OECD, 2019) on teacher self-reported motivations for joining the teaching force were reviewed together with World Bank indicators on average life opportunities and inequality. Specifically, the Human Capital Index (HCI) and Gini estimates for income distribution (World Bank, 2021; 2022). As noted by Kranich, equity as a term in education contexts stands for stances that seek to mitigate social disadvantage (Kranich, 2005). Data on such stances, among other, were collected in the TALIS 2018 survey.

TALIS data was downloaded from the OECD website and was transferred to Excel sheets using the SPSS software package. A total of 48 countries participated in TALIS 2018; data from fourteen of the 48 countries is used for illustrating teacher stances. This convenience sample consists of country data extracted from one data-file download from the OECD website. Descriptive data for the fourteen countries available in one data download was processed systematically, it however does not represent the full data set of 48 countries and is used here to illustrate a discussion. The sample was not extracted, nor was it analysed for testing statistical significance nor causal relationships. The secondary use of the data presented is done here for purely descriptive purposes, with the primary purpose of raising questions about expectations to the role of teachers in mitigating societal inequity and to illustrate recurrent characteristics in the data by juxtaposing teacher responses and macro-societal circumstances in fourteen countries. Whereas some of the premises here are induced from the data, such as a universal agreement among teachers that they in their professional role are expected to mitigate societal inequities, may intuitively make sense to many, I have nevertheless chosen for the sake of rigor to show the data that in a recent TALIS study supports such an idea. Rather than taking for granted that there is a broad agreement that teachers are expected to mitigate societal inequities, I have found it valuable to see what and how 47985 teachers have in 2018 responded on this thematic.

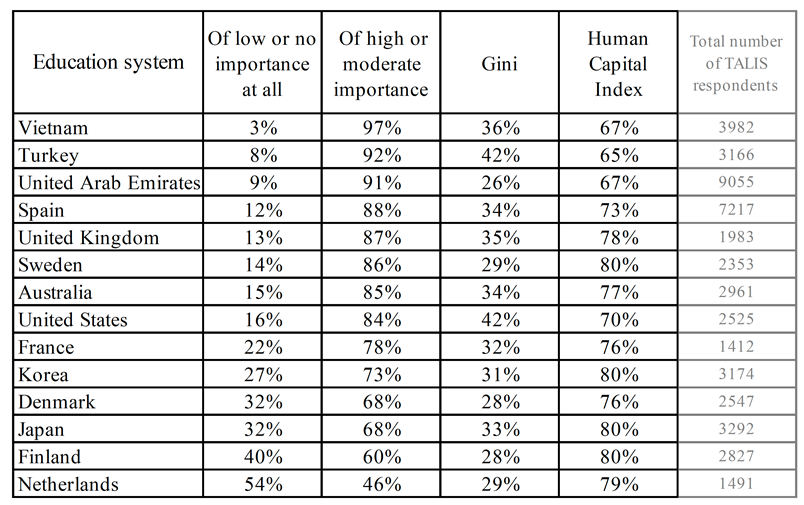

Table 1. Motivation to benefit the socially disadvantaged, for decision to become a teacher, by country

Source: Table constructed by Wiksten May 2022, using data retrieved August 2019 from the OECD’s TALIS survey at http://www.oecd.org/education/talis/. The table shows teachers’ self-reported answers to question 7 on reasons teachers perceived as important for their decision to become a teacher, specifically for the proposal Teaching allowed me to benefit the socially disadvantaged (TT3G07F). The four answer options consisted of (1) no importance at all, (2) of low importance, (3) of moderate importance and (4) of high importance. The second column lists percentages of respondents who responded either option 1 or 2 (of no importance at all, or of low importance). The third column of this table gives the percentage of respondents who responded either option 3 or 4 (of moderate importance, or of high importance). Gini values retrieved May 2022 from the World Bank at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI. HCI values are from the World Bank, 2021, The Human Capital Index 2020 Update, p. 41. It is good to note that the World Bank aggregates recent data for its various publications, not all of the data is from the same year (or only one year).

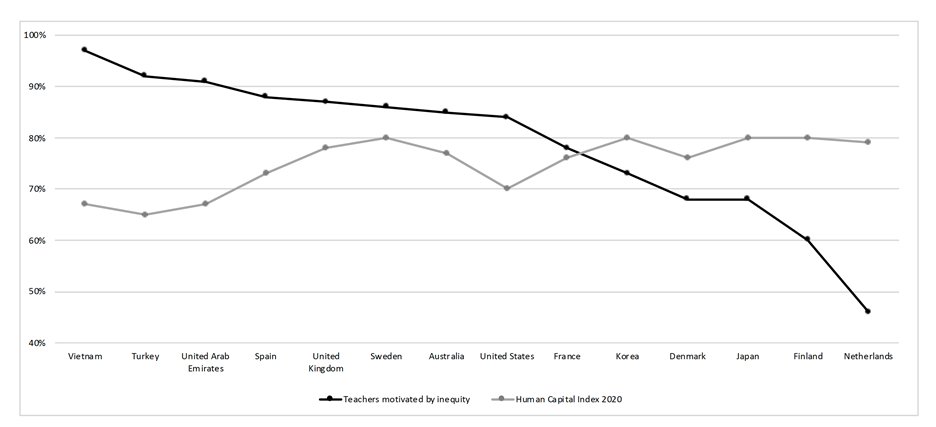

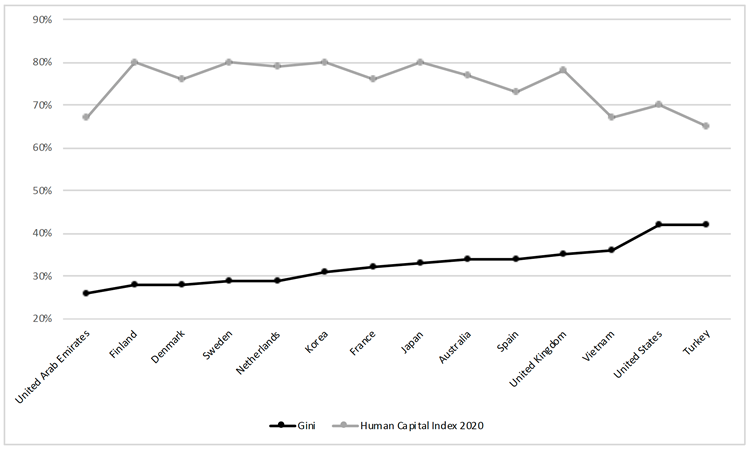

Secondary analysis consisted of organizing the data in Excel, calculating percentages and juxtaposing the data with Gini and Human Capital Index (HCI) values from the World Bank. Graphs presented in Figures 1 and 2 were constructed using Excel to illustrate teacher motivation in relationship to HCI values and to illustrate HCI values in relationship to Gini values. The HCI is an aggregate indicator constructed by the World Bank for comparing life opportunities across countries. HCI combines data on health, life expectancy and education (World Bank, 2022b). Gini values are used for comparing disparities in income distribution across countries. Figure 1 demonstrates that comparatively higher teacher motivation to join the profession to benefit the socially disadvantaged coincide with a lower HCI ranking by country, in this comparison of fourteen countries.

Figure 1. Teacher motivation to benefit the socially disadvantaged and average life opportunities in terms of education and health

Source: Figure constructed by Wiksten, May 2022, using data retrieved August 2019 from the OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) at http://www.oecd.org/education/talis/. The table shows teachers’ self-reported answers to question 7 on reasons teachers perceived as important for their decision to become a teacher, the table shows answers specifically for the proposal Teaching allowed me to benefit the socially disadvantaged (TT3G07F). HCI values are from the World Bank, 2021, The Human Capital Index 2020 Update, p. 41.

Figure 2 illustrates that a larger number of countries with comparatively higher inequality, as measured by Gini values, tend to rank comparatively lower in the HCI. Even though this may intuitively make sense, I nevertheless value demonstrating with recent data, rather than build my argument on an assumption. A point underscored in this article is that expectations to the role of teachers and their performance as professionals are impacted by the macro-societal context, which is different between countries. The data indicates a relationship between teacher motivation and average life opportunities in individual countries, as measured by the HCI. The point of showing this is that while we recognize that there are differences among teachers, this data indicates that some teacher attitudes are not only a result of characteristics specific to individual teachers or the teacher profession in general but are associated with variation between countries. This point, which is not often taken into consideration in discussions about teacher education development and the assessment of teacher competence — notably when these features are perceived primarily as national concerns framed by national policy — nevertheless is illustrated saliently in international and comparative education research (Torres et al., 2022; Wiksten & Green, 2021). The fact that transnational variation is not consistently recognized adds unreasonable expectations on teachers by exerting an external pressure on the teacher profession. It is important to recognize and problematize societal pressures that derive from a context that is external to the teacher profession because decisions required for changing the societal context are fundamentally political and belong to the domain of societal governance, thereby representing political efforts beyond the scope of the teacher profession. Circumstances that teachers can do very little about represent an unreasonable and demotivating pressure on teachers. In the following, and as further elaborated in the second part of this article, I propose investment in teachers’ PDM skills as one way for addressing this problematic dynamic in teacher education.

Figure 2. Human Capital Index and inequality

Source: Figure constructed by Wiksten in May 2022. Gini values retrieved May 2022 from the World Bank at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI. HCI values are from the World Bank, 2021, The Human Capital Index 2020 Update, p. 41.

Two assertions are supported with the data in Table 1 and Figures 1–2; namely that: (1) teachers in comparatively higher inequity countries are under greater pressure to take on a politically motivated role in their professional role as teachers; (2) an uneven but consistent tendency can be seen in the data in which comparatively greater life opportunities on average (by HCI), and comparatively lower inequity (by Gini) are associated with fewer teachers joining the profession for mitigating societal inequities. It is as if teachers knew whether inequity was high in their country, and if so, they perceived it as their duty to mitigate it. This pattern in the data holds across the fourteen countries compared. It is not surprising to note that teachers are likely to know the societal context in which they work. However, the data also indicates an almost universal agreement among teachers from different world regions, that a key professional role of teachers is to contribute to the mitigation of societal inequities. Teachers are in their professional role expected to mitigate societal inequities by contributing to the life opportunities of all students. This normative stance was reaffirmed by respondents in the TALIS 2018 study. As will be discussed in the discussion section, such a belief, aspiration, and expectation, faces several challenges.

Factors that contribute to constraints for teacher agency for mitigating inequity include policy driven dynamics for excessive focus on competition; and control on micro-level in classrooms, on the meso-level in terms of local policies for education and on the macro level in terms of national and transnational education policies. Another constraining factor is that teacher education and the teaching profession are not in a position to change macro-societal contexts and political decisions in individual countries. Shifting focus in education policies, contexts and practices towards humanizing and deliberative practices is proposed in the following section of this article as a viable and concrete option that would better allow for room to develop an active and meaningful role for teachers as professionals, to contribute to the mitigation of inequity. In this vein, teacher education programs are recommended—to better respond to the expectation that teachers mitigate societal inequities—to invest in strengthening the development of teacher’s pedagogical decision-making (PDM) skills as a reflective practice among teachers, for teachers to better withstand external and political pressures. In particular, for supporting teacher agency and motivation (Giddens, 1986) which in line with self-determination theory (Deci et al., 1991) are key for supporting teacher professionalism, autonomy and resilience. The PDM skills necessary for responding constructively to external and political pressures focus on skills relevant for (1) reasoning about the choice of teaching-learning practices used, (2) adjusting curricula to respond to the needs of diverse and different groups of students in order to improve relevancy, (3) continued self-evaluation and reflection on teaching practices in order to improve and continue adjusting practices, (4) connecting pedagogical approaches, pedagogical theories and knowledge from research and inquiry to everyday decisions concerning teaching and learning practices used.

Discussion

Comparative and International perspectives on the development of education, teachers and competence

Comparative International Education (CIE) as a field of study has evolved to support the development of education internationally (Wiksten, 2020). Building on the idea that education in every country can be improved (Arnove et al., 1992) and that comparing stances, understandings and experiences from different countries can contribute important insights to the development of education and education policies internationally draws in this field of research on multiple perspectives (Maurič & Scherling, 2021; Torres et al., 2022). The approach engaged in the analysis in this article draws notably on critical stances that draw on research in the political sociology of education, teacher education research as well as literature on education development and the development of competences (Lewin, 2010; Lokhoff et al., 2010; Maurič & Scherling, 2021; Morrow & Torres, 1995; Torres, 2016; Wiksten, 2020; Wiksten, 2019; 2020; 2021)

This perspective aligns with critical comparative global education approaches (Wiksten, 2021), according to which students have a need to understand how current challenges for sustainable development in terms of social phenomena such as poverty and in terms of environmental issues such as the conditions of life on land and in the seas, are connected and relevant at the local, regional and the global levels.

CIE research is particularly helpful for shedding light on topics that pertain to the social context of education, as comparisons of e.g. the expectations of teachers in relation to societal change (Wiksten & Green, 2021) are so thoroughly engrained in societies that we tend to take them for granted. This habit to assume norms without questioning is a feature that renders most unaware of societal power relations in the everyday and can make the articulation of boundaries for expectations difficult for teachers. This is in the long run detrimental as it dissuades teachers from addressing uncomfortable topics such as power dynamics. Critical CIE stances have pointed out as one of the challenges to UN agenda various inefficiencies that derive from lacking representation and voice from local communities and historical minorities (Andreotti & de Souza, 2012; Freire, 1970; Morrow, 2021). Instead, structured coordination for supporting grassroots engagement is needed, and approaches to support teachers to engage with students to support motivated student participation.

Critical comparative perspectives underscore dialogical and humanizing features of education (Freire, 1970). In this perspective, competing views and ideologies need to be recognized and negotiated in education to support students to achieve and reflect on different perspectives (Desjardins et al., 2020). The development of shared references in education, such as promoted by the Bologna Process (Donà dalle Rose & Serbati, 2019; EU legislation, 2015) and other efforts to promote standards, is in many ways a positive development. However, the coinciding broader shift from classroom-based evaluation of students to summative testing for other purposes than classroom instruction has contributed to a devaluation of the recognition of the evaluative expertise of teachers. Teacher education should in line with critical and humanizing approaches revalorize the role of teachers as experts and analysts of the cognitive advances of students. In this view, the use of formative evaluation for strengthening purposive instruction is underscored.

Pedagogical Decision Making

Modeling and mimicking are basic teaching and learning mechanisms. Already young children learn by observing parents and siblings and by mimicking their actions. These are teaching and learning practices that are intuitive and are typically not reflected on. Learning by doing and by following the model of older people is a key dynamic in traditional societies— a traditional way of transferring knowledge from one generation to another e.g. in agricultural contexts. Lave and Wenger have in this vein studied learning through participation in communities of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991). Modeling, mimicking and storytelling have played a central role in the transfer of knowledge from one generation to another across human societies.

The learning of complex advanced forms of knowledge, skills and practices requires the mobilization of knowledge, skills, attitudes and values which all contribute to what is referred to as competence (Lokhoff et al., 2010). In practice, competence is about the ability to use knowledge in meaningful and practical ways. Drawing on research on human cognitive development, the United Nations education agenda recognizes that education has cognitive, behavioral, and socio-emotional objectives (UNESCO, 2017).

Using the term pedagogical decision-making (PDM) skills for the first time in this article, I draw on my prior research on teacher education (Wiksten, 2018; 2019; 2020; 2021; Wiksten & Green, 2021) and practices I have developed in teaching students in teacher education in my previous work at UCLA. A key tenet of how I understand PDM, and why I propose it is important that particular attention is given to the development of a set of complex metacognitive skills, is that learning the skills, knowledge and practices required to function competently as a teacher is demanding. To succeed, it does not suffice to be well-versed in a specific subject matter content area. It is important that teachers gain competence in three domains in addition to subject matter content. Key features of teachers PDM skills include the ability to address: (1) social assumptions, (2) unreasonable expectations, (3) skills in articulating how the decision to use specific teaching and learning practices are informed by experience, inquiry and bodies of scholarship. In the following, I provide examples and references from the literature on knowledge and skills that teachers need to develop for addressing these three points that are central for my definition of PDM skills. The examples in the following are used for illustrating why it is important that teachers in all subject matter areas are supported to develop PDM skills.

Social assumptions

To support teachers to develop the necessary knowledge and skills for addressing social assumptions, it is crucial that teacher education programs support teachers to develop a sociological imagination or sociological consciousness (Berger, 1963; Delamont, 2012; Mills, 1959). Because human existence and our everyday lives are squarely rooted in social circumstances, explicit effort and reflection out of the ordinary is required, to understand—let alone to attempt to guide—social interaction such as it occurs in classrooms. The development of social imagination enables efforts to understand the complex role that social norms, social categories and social context play for supporting and constraining communication and interactions in educational settings.

Many expectations guide the behavior of teachers and students, these expectations are associated with social categories such as age, gender, race, ethnicity, disability and other socially constructed categories. For education to interrupt the reproduction of bias such as racism, xenophobia or misogyny in education, it is first necessary to recognize the pervasive role of hegemonic common-sense assumptions associated with social categories in the context of education (Chan & Jafralie, 2021; Dei, 2014; Gramsci, 1971; Shah, 2015). For understanding many of the different expectations under which both teachers and students work, it is necessary to reflect in explicit analytical and conscious ways also on the norms that guide behaviors and expectations in the context of education. These are not simply rules for behavior but reflect power dynamics in societies (Freire, 1970; Lanas et al., 2022), dynamics that can contribute to what Rothstein (2005) refers to as social traps. Social traps, in a nutshell, are circumstances that form when distrust feeds distrust in a negative cycle that ends up working against shared interests in education. Education is here understood, as proposed in critical approaches (Freire, 1970; Morrow, 2021), a common good resource in that it benefits from a degree of negotiation and coordination of shared decisions and references—such as value frameworks—by those who provide it, participate in it and benefit from it (Desjardins et al., 2020; Ostrom, 1990).

To support teachers to become better at pedagogical decision making, to build trust, and to make well-reasoned decisions about the instruction practices that teachers choose to use, it is necessary that teachers develop their sociological consciousness. This will help them to better identify their own positionality, the social context in which they instruct, and the challenges individuals face due to social norms associated with social categories. As noted by Stromquist (2015) and Shah (2015), it is not enough for increasing equity, that girls and women gain access to education, if gender-based expectations and norms are not addressed in explicit ways in instruction.

This first dimension of meaningful pedagogical decision making is about learning how to identify, recognize and address norm-based assumptions that are often learned without reflection through modelling. It is particularly important for this reason that explicit efforts in teacher education are made to support teachers to develop critical and analytical skills for reflecting on norms and social categories, to interrupt the reproduction of existing biases. Interrupting biases is not only an important ethical issue. It also contributes to the efficiency of education, because alienating experiences undermines intrinsic motivation important for students to develop higher order cognitive skills (Deci et al., 1991).

Questioning expectations is important

As societies continue to change due to global developments such as pandemics and wars, as well as technological, economic and environmental changes, instruction practices require continuous updating. Societal structural changes impact teacher education in several different ways that include the need to update (1) subject matter specific knowledge; (2) knowledge about teaching and learning practices; (3) adaptation to technological change; (4) address challenges presented by environmental change and natural disasters, pandemics, political violence; and (5) socio-cultural and political expectations.

Patterns demonstrated in responses from teachers and principals (TALIS 2018) were reviewed in the previous section on data. In a CIE perspective and using the Occam’s razor principle as an analytical tool (Myung & Pitt, 1997), the data patterns illustrate that teachers are, in all the observed fourteen countries, expected to mitigate societal inequity. More specifically, this was documented as an important factor that motivated respondents’ decisions to pursue a teaching career. The Occam’s razor principle in analysis means that the simplest explanation is favored between alternative possible explanations, other explanations remain possible.

How teachers are expected to mitigate societal inequities varies across countries, as illustrated in a comparison of beliefs regarding the role of teachers in the US, Japan and Finland (Wiksten & Green, 2021). The role of teachers as agents of societal change was underscored in the US, whereas the teachers’ role in Japan underscored the sustenance of stable societal relations between different groups in society. In Finland, teachers were understood to play an important role in continuously updating instruction practices to better meet the changing needs of diverse societal groups (Wiksten & Green, 2021).

The motivation to join the teaching force to mitigate societal inequities is greater in countries experiencing comparatively higher levels of inequity (Table 1, Figures 1-2). This juxtaposition of TALIS and World Bank Data comparing fourteen countries across four different continents demonstrates that, on average, lower life opportunities in a country—as measured by the HCI—coincide with a higher self-reported motivation among teachers to join the profession to support those who are disadvantaged in society (Table 1, Figure 1). Gini rates, which is a measure for inequality in income distribution, coincide in this comparison with a comparatively lower HCI ranking (Figure 2). The interpretation proposed here as the plausible explanation for the patterns observed in the data in Table 1 and Figures 1 and 2 is that (1) greater societal inequity (by Gini) tends to coincide with on average fewer life opportunities in terms of health and education (by HCI). This in turn leads to a situation in which (2) teachers working in contexts of greater inequity experience greater pressure to address societal inequity. The latter manifests in the data as a higher percentage of teachers joining the teaching force to mitigate societal inequities (Table, 1, Figure 1)—in brief, the internalized motivation for joining the teaching force reflects external pressures.

Achieving greater societal equity is a political goal for societies that require negotiation between societal actors. In liberal democratic societies the negotiation of societal resources has been assigned to political representatives and the government. Negotiations are demanding, require the coordination of several actors in liberal democratic regimes, are imperfect and never fully achieved. As such, societal negotiation of resources is largely beyond the purview and day-to-day work of individual teachers (Apple, 2009; 2013). While critical consciousness raising is relevant in education and can feasibly be part of the curriculum (Berkovich, 2014; Desjardins et al., 2020; Freire, 1970; Grundtvig, 1832/1984; Harva, 1983; Morrow, 2021), political activism as such does not belong in the professional profile of the teacher—if teachers are required to achieve more than political indoctrination and are to be responsible for providing quality instruction to diverse groups of learners (Wiksten, 2021). Indeed, the role of teachers can in varying degrees be defined as a professional role or a political role—either as serving the development of advanced cognitive competence (Noddings, 2014; Vygotsky, 1978) or serving the role of representatives of the nation state, political interest groups or factions. In fact, even in what has traditionally been perceived as somewhat value-neutral basic education for all in the context of the nation state, the two roles overlap (Collins, 2008; Foucault, 1995; Green, 1990; Meinander, 2005). What tends to be perceived as value neutrality in mainstream education, usually reflects the fact that certain values have become broadly accepted—to the extent that established norms are accepted in everyday practices and are not questioned or problematized (Abdi, 2017; Gramsci, 1971; Stromquist, 2015).

Connecting to bodies of knowledge in education

The development of PDM skills among teachers is necessary for responding in balanced and constructive ways to external pressures and to support teacher resilience through professional development. The proposition that the development of PDM skills among teachers is an important driver of quality, teacher resilience and a sustained development of education builds in this article on two premises: (1) there is broad support among teachers and principals for the idea that teachers need to contribute to the mitigation of societal inequities in their professional role (Table 1; Figure 1; OECD, 2019)—to the extent that is feasible; and (2) that teachers can better mitigate societal inequities in education when exercising autonomy in pedagogical decision making—so that teachers can withstand the crossfire of socio-cultural expectations and political pressures under which they work.

I define PDM skills in this article as skills in (1) reasoning about the choice of teaching-learning practices used, (2) adjusting curricula to respond to the needs of diverse and different groups of students in order to improve relevancy, (3) continued self-evaluation and reflection on teaching practices in order to improve and continue adjusting practices, (4) skills in connecting pedagogical approaches, pedagogical theories and knowledge from research and inquiry to practice (see also Wiksten, 2020). Key goals for the development of these four components that contribute to PDM skills are for teachers to gradually (1) abandon prior models of dysfunctional, obsolete, and inappropriate practices in education (such as unintentionally or intentionally single-minded perspectives, dehumanizing and alienating practices); (2) to advance the use of intrinsically motivating, in-depth and holistic learning practices (Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Deci et al., 1991; hooks, 2009; Järvelä et al., 2000; Noddings, 2014; Vygotsky, 1978); (3) supporting teachers to become critically conscious and autonomous professionals able to engage in authentic dialogue with students (Morrow, 2021). The latter point is central for advancing quality and equity in education and a sustained development of education that is necessary for responding to the continuously changing societal contexts in which teachers work.

Modern practices that seek to enforce education accountability for bureaucratic purposes are sought after in contexts of increasing competition. This and practices promoting competition in classrooms can lead to the frequent use of summative evaluations and may leave less time and attention to formative evaluation practices in education. Both above tendencies are counterproductive for both metacognitive and intrinsically motivated forms of learning that are more efficient for the development of higher order thinking skills (Deci et al., 1991)—albeit more difficult to evaluate. However, as these challenges fundamentally derive from education policy decisions, it is also possible to address and counter these challenges with education policies. Notably, as proposed in this article, through policies that underscore the importance of supporting the development of PDM skills among teachers.

The need for coordinated efforts to advance PDM in education

Coordination of efforts to advance PDM are needed, because uncoordinated reliance on civil society, private providers and philanthropy (Avelar, 2019; Schervish, 2003; Zero & Zero Soares, 2021) are not sustainable alternatives. Ongoing societal changes, including global structural changes since 2020 are increasing societal inequities globally and are adding to the load of societal and political pressures that manifest in the everyday of teachers and students. In particular, teachers and students need support to discuss, reason about and consider, in explicit and nuanced ways, the topics of (1) diverse worldviews including religious and non-religious groups, (2) social categories including but not limited to gender, race, sexual orientation and first language, (3) environmental concerns, (4) media literacy, (5) power and resource issues.

The influence of the role of entertainment in the form of computer games, software applications used on smartphones, and social media has increased as the primary source of knowledge, news and information for students (Share et al., 2023/2019). Without investment in humanizing teaching practices, the prominence of such media in forming the worldview of students, as the primary drivers of intrinsic motivation in learning, will disproportionately increase, to the detriment of instruction that is relevant for the development of higher order thinking skills. Uncritically received social media messages that appeal to student emotions, together with increasing societal pressures for competition and testing focused alienating practices in education, are conducive to aggravating negative and divisive socio-emotional developments among students (Harmon, 2022).

Building trust in the context of a classroom is a time consuming but necessary first step enabling to proceed with any form of nuanced dialogue with students (Wiksten, 2018). Students need to experience generosity from the teacher in terms of possibilities to express tentative articulations of stances on varieties of issues in the classroom (except for hate-speech); if students perceive no such generosity, they will very effectively disengage from education. Student-centred and humanizing teaching and learning practices recognize that students need to develop skills in articulating their stances on the above five themes ranging from diverse worldviews to power and resource issues. These themes are not relevant only for a specific subject matter but are relevant across subject matter curricula. The reason for this is that students need to develop their ability to express informed stances on cross-cutting societal issues to experience education as relevant to their own life experiences. This is a fundamental necessity for meaning-making, for meaningful learning, and for intrinsically motivated education that supports the development of higher order thinking skills (Deci et al., 1991; Vygotsky, 1978; Wiksten, 2019).

Efforts to meet challenges in education, such as mitigating inequity, call for contributions from a broad range of government and non-governmental actors. However, the alternatives of simply continuing as before or hoping for market forces to take care of the coordination of a complex common good resource such as education (Torres & Bosio, 2020) are counterproductive, insufficient and unsustainable as approaches. Instead, I have discussed using TALIS and HCI data, that the development of what I conceptualize and term PDM skills is a constructive way to enable and empower teachers to effectively respond to challenges such as the need to mitigate inequity. Key PDM skills identified in this article, are skills in (1) reasoning about the choice of teaching-learning practices used, (2) adjusting curricula to respond to the needs of diverse and different groups of students in order to improve relevancy, (3) continued self-evaluation and reflection on teaching practices in order to improve and continue adjusting practices, and finally (4) skills in connecting pedagogical approaches, pedagogical theories and knowledge from research and inquiry to practices.

Limitations

Publicly available descriptive data used in this article for contextualizing the point that teacher education can respond to macro-societal pressures by supporting the development of teachers’ skills can be viewed, interpreted and discussed from a variety of perspectives. I have used a comparative international education approach (CIE) to analyse the active role of teachers’ pedagogical decision making in instruction. In a CIE perspective, there are several possible lenses that can be used for analysing cross-national comparative data. In this article, data was used for a descriptive comparison of contexts, for highlighting variation in teacher attitudes and expectations to the role of teachers in serving socially disadvantaged students. My hope is that the reasoning that I provide for arguing that teachers need support for developing pedagogical decision-making skills (PDM) will feed further discussions on cross-cutting themes that are relevant in teacher education, notably for supporting teacher resilience, to address challenging topics in instruction, and encourage a broader use of descriptive data for posing questions and problematizing assumptions about teacher education.

References

Abu El-Haj, T. R. (2023). Against Implications: Ethnographic Witnessing as Research Stance in the Lebanese Conflict Zone. Comparative Education Review, 67(2), 231–250. https://doi.org/10.1086/724175

Ahmed, K. S. (2019). Against the Script With edTPA: Preservice Teachers Utilize Performance Assessment to Teach Outside Scripted Curriculum. Urban Education, 58(4), 614-644. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085919873689

Anderson-Levitt, K., van Draanen, J., & Davis, H. M. (2017). Coherence, dissonance, and personal style in learning to teach. Teaching Education, 28(4), 377–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2017.1306505

Andreotti, V.D.O., & de Souza, L. M. T. M. (Eds.). (2012). Postcolonial Perspectives on Global Citizenship Education. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203156155

Apple, M. W. (2009). Can critical education interrupt the right? Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 30(3), 239–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596300903036814

Apple, M. (2013). Can education change society? Routledge.

Arnove, R., Altbach, P., & Kelly, G. (1992). Emergent Issues in Education: Comparative Perspectives. SUNY Press.

Avelar, M. (2019). O público, o Privado e a Despolitização nas Políticas Educacionais. In F. Cássio (Ed.), Educação contra a Barbárie (pp. 73–79). Boitempo.

Berger, P. L. (1963). Invitation to Sociology: A Humanistic Perspective. Anchor.

Berkovich, I. (2014). A socio-ecological framework of social justice leadership in education. Journal of Educational Administration, 52(3), 282–309. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-12-2012-0131

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

Cedillo, C., & Bratta, P. (2019). Relating Our Experiences: The Practice of Positionality Stories in Student-Centered Pedagogy. College Composition and Communication, 71(2), 215–240. https://doi.org/10.58680/ccc201930421

Chan, W. Y., & Jafralie, S. (2021). Civic religious literacy as a form of Global Citizenship Education: Three examples from practitioner training in Canada. In S. Wiksten (Ed.), Centering Global Citizenship Education in the Public Sphere: International Enactments of GCED for Social Justice and Common Good (pp. 114–129). Routledge.

Collins, M. (2008). Rabindranath Tagore and Nationalism: An Interpretation. Heidelberg Papers in South Asian and Comparative Politics, 42. https://doi.org/10.11588/hpsap.2008.42.2210

Darling-Hammond, L., Holtzman, D.J., Gatlin, S. J. & Heilig, J.V. (2005). Does Teacher Preparation Matter? Evidence about Teacher Certification, Teach for America, and Teacher Effectiveness. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 13(42), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v13n42.2005

Deci, E. L., Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). Motivation and education: The self-determination perspective. Educational Psychologist, 26(3–4), 325–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.1991.9653137

Dei, G. (2014). Personal reflections on anti-racism education for a global context. Encounters/Encuentros/Rencontres on Education, 15, 239–249. https://doi.org/10.24908/eoe-ese-rse.v15i0.5153

Delamont, S. (2012). Handbook of Qualitative Research in Education. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Desjardins, R., Torres, C. A., & Wiksten, S. (2020). Social Contract Pedagogy: A Dialogical and Deliberative model for Global Citizenship Education. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374879

Donà dalle Rose, L. F., & Serbati, A. (2019). 20th Anniversary of the Bologna Declaration: From overview of processes to ongoing activities and experiences. Tuning Journal for Higher Education, 6(2), 13–19. https://doi.org/10.18543/tjhe-6(2)-2019pp13-19

Eisenbach, B. B. (2012). Teacher Belief and Practice in a Scripted Curriculum. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 85(4), 153–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2012.663816

EU legislation (2015). The Bologna process: Setting up the European higher education area. European Union Publications Office. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=LEGISSUM:c11088

Federičová, M. (2021). Teacher turnover: What can we learn from Europe? European Journal of Education, 56(1), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12429

Foucault, M. (1995). Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Vintage Books.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Continuum.

García-Arroyo, J. A., Osca Segovia, A., & Peiró, J. M. (2019). Meta-analytical review of teacher burnout across 36 societies: The role of national learning assessments and gender egalitarianism. Psychology & Health, 34(6), 733–753. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2019.1568013

Giddens, A. (1986). The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. University of California Press.

Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks. International Publishers Co.

Green, A. (1990). Education and State Formation: Europe, East Asia and the USA (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

Grundtvig, N. F. S. (1984). A Grundtvig Anthology: Selections from the Writings of N.F.S. Grundtvig, 1783-1872. J. Clarke., (Original work published 1832).

Harmon, J. (2022, April 26). Facebook whistleblower and director of ‘The Social Dilemma’ talk about social media’s impact. UCLA Newsroom. https://newsroom.ucla.edu/stories/frances-haugen-jeff-orlowski-yang-ramesh-srinivasan-common-experience

Harva, U. (1983). Inhimillinen ihminen: Humanistisia tarkasteluja [Education in humanist perspectives]. WSOY.

hooks, b. (2009). Teaching Critical Thinking: Practical Wisdom. Routledge.

Järvelä, S., Lehtinen, E., & Salonen, P. (2000). Socio-emotional Orientation as a Mediating Variable in the Teaching‐Learning Interaction: Implications for instructional design. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 44(3), 293–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/713696677

Köhler, T. (2022). Class size and learner outcomes in South African schools: The role of school socioeconomic status. Development Southern Africa, 39(2), 126–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2020.1845614

Kranich, N. (2005). Equality and Equity of Access: What’s the Difference? American Library Association.

Lanas, M., & Brunila, K. (2019). Bad behaviour in school: A discursive approach. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 40(5), 682–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2019.1581052

Lanas, M., Petersen, E. B., & Brunila, K. (2022). The discursive production of misbehaviour in professional literature. Critical Studies in Education, 63(3), 355–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2020.1771604

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511815355

Lewin, R. (Ed.). (2010). The Handbook of Practice and Research in Study Abroad: Higher Education and the Quest for Global Citizenship. Routledge.

Liu, J., & Bray, M. (2020). Accountability and (mis)trust in education systems: Private supplementary tutoring and the ineffectiveness of regulation in Myanmar. European Journal of Education, 55(3), 361–375. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12409

Lokhoff, J., Wegewijs, B., Durkin, K., Wagenaar, R., González, J., Isaaks, A. K., Donà dalle Rose, L. F., & Gobbi, M. (Eds.) (2010). A Tuning Guide to Formulating Degree Programme Profiles: Including Programme Competences and Programme Learning Outcomes. Universidad de Deusto.

Meinander, H. (2005). Discipline, Character, Health: Ideals and Icons of Nordic Masculinity 1860-1930. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 22(4), 600–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523360500122905

Mills, C. W. (1959). The Sociological Imagination (40th anniversary edition). Oxford University Press.

Morrow, R. A. (2021). From deliberative to contestatory dialogue: Reconstructing Paulo Freire’s approach to critical citizenship literacy. In S. Wiksten (Ed.), Centering Global Citizenship Education in the Public Sphere: International Enactments of GCED for Social Justice and Common Good (pp. 42-55). Routledge.

Morrow, R. A., & Torres, C. A. (1995). Social Theory and Education: A Critique of Theories of Social and Cultural Reproduction. SUNY Press.

Myung, I. J., & Pitt, M. A. (1997). Applying Occam’s razor in modeling cognition: A Bayesian approach. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 4(1), 79–95. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03210778

Noddings, N. (2014). Cosmopolitanism, Patriotism, and Ecology. In R. Bruno-Jofré & J. S. Johnston (Eds.), Teacher Education in a Transnational World (pp. 96–108). University of Toronto Press.

OECD. (2019). TALIS 2018 Data. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. http://www.oecd.org/education/talis/talis-2018-data.htm

OECD. (2022). Population and employment by main activity. OECD.Stat. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SNA_TABLE3#

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press.

Placklé, I., Könings, K. D., Jacquet, W., Libotton, A., van Merriënboer, J. J. G., & Engels, N. (2022). Improving student achievement through professional cultures of teaching in Flanders. European Journal of Education, 57(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12504

Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., Haverinen, K., Tikkanen, L., & Soini, T. (2021). Teacher burnout profiles and proactive strategies. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 36(1), 219–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-020-00465-6

Rothstein, B. (2005). Social traps and the problem of trust. Cambridge University Press.

Schanzenbach, D. W. (2020). The economics of class size. In S. Bradley & C. Green (Eds.), The Economics of Education (2nd ed.) (pp. 321–331). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815391-8.00023-9

Schervish, P. G. (2003). Hyperagency and high-tech donors: A new theory of the new philanthropists. Social Welfare Research Institute, Boston College. https://ur.bc.edu/islandora/hyperagency-and-high-tech-donors

Shah, P. (2015). Spaces to Speak: Photovoice and the Reimagination of Girls’ Education in India. Comparative Education Review, 59(1), 50–74. https://doi.org/10.1086/678699

Share, J., Mamikonyan, T., & Lopez, E. (2023). Critical Media Literacy in Teacher Education, Theory, and Practice Jeff Share, University of California Los Angeles, Tatevik Mamikonyan, University of California Los Angeles, and Eduardo Lopez, University. Oxford Research Encyclopeadia. (Original article published 2019). https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1404

Stromquist, N. P. (2015). Women’s Empowerment and Education: Linking knowledge to transformative action. European Journal of Education, 50(3), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12137

Tien, J. (2019). Teaching identity vs. positionality: Dilemmas in social justice education. Curriculum Inquiry, 49(5), 526–550. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2019.1696150

Torres, C.A. (2016). The Making of a Political Sociologist of Education. In A. R. Sadovnik & R. W. Coughlan (Eds.), Leaders in the Sociology of Education: Intellectual Self-Portraits (pp. 231-252). Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-717-7_16

Torres, C. A., Arnove, R., & Misiaszek, L. I. (Eds.) (2022). Comparative Education: The Dialectic of the Global and the Local (5th ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

Torres, C. A., & Bosio, E. (2020). Global citizenship education at the crossroads: Globalization, global commons, common good, and critical consciousness. PROSPECTS: Comparative Journal of Curriculum, Learning, and Assessment, 48, 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-019-09458-w

UNESCO. (2017). Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning objectives. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022). Employment by major industry sector. https://www.bls.gov/emp/tables/employment-by-major-industry-sector.htm

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds.; New edition). Harvard University Press.

Wiksten, S. (2018). Teacher Training in Finland: A Case Study [Doctoral dissertation]. University of California, Los Angeles. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1kk7c3bz

Wiksten, S. (2019). Talking About Sustainability in Teacher Preparation in Finland and the United States. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education (NJCIE), 3(1), 69–87. https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.3302

Wiksten, S. (2020). A critically informed teacher education curriculum in Global Citizenship Education: Training teachers as field experts and contributors to assessment and monitoring of goals. Journal of International Cooperation in Education, 23(2), 107–130. https://cice.hiroshima-u.ac.jp/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/8.Susan_.pdf

Wiksten, S. (Ed.). (2021a). Centering Global Citizenship Education in the Public Sphere: International Enactments of GCED for Social Justice and Common Good. Routledge.

Wiksten, S. (2021b). Introduction: Critical Global Citizenship Education as a Form of Global Learning. In S. Wiksten (Ed.), Centering Global Citizenship Education in the Public Sphere: International Enactments of GCED for Social Justice and Common Good (pp. 1-13). Routledge.

Wiksten, S., & Green, C. (2021). Expectations to teachers’ role in advancing society and equity in Finland, Japan and the United States: Findings from TALIS 2018. In S. Wiksten (Ed.), Centering Global Citizenship Education in the Public Sphere: International Enactments of GCED for Social Justice and Common Good (pp. 99–113). Routledge.

Woods, P., & Jeffrey, B. (2021). Teachable Moments: The Art of Teaching in Primary Schools. Routledge.

World Bank. (2021). The Human Capital Index 2020 Update. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/34432/9781464815522.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y

World Bank. (2022). GINI index (World Bank estimate). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI

Zero, M. A., & Zero Soares, A. (2021). Advancements and Limitations in Brazil’s Democratic Management of Education framework. In S. Wiksten (Ed.), Centering Global Citizenship Education in the Public Sphere: International Enactments of GCED for Social Justice and Common Good (70-84). Routledge.

Zhang, W. (2020). Shadow education in the service of tiger parenting: Strategies used by middle‐class families in China. European Journal of Education, 55(3), 388–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12414