Vol 9, No 4 (2025)

https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.6174

Article

Teacher perceptions of digital life skills in upper secondary school: Digital detox, footprints and responsibility

Anja Ramfjord Isaksen

Institution: Department of Teacher Education and School Research, University of Oslo

Email: a.r.isaksen@ils.uio.no

Greta Björk Gudmundsdottir

Institution: Department of Teacher Education and School Research, University of Oslo

Email: g.b.gudmundsdottir@ils.uio.no

Abstract

The introduction of a new curricular reform in 2020 led to life skills becoming a widely discussed topic in Norway. Other commonly debated topics are young people’s technology use and time spent online. Their lives seem intricately dependent on technology and social media, which highlights a need to address societal pressures, including mental health, exclusion and online risks in their education. Given these developments, it has become important to further examine digital life skills to address the juxtaposition between digital technologies and life skills in young people’s lives to capture these challenges and understand how they are addressed in school. This study aims to enrich existing research by examining the concept of digital life skills and contributing to the conceptualisation of this concept through teachers’ perspectives in Norway. We interviewed 13 upper secondary school teachers from general and vocational study programmes to capture their views on the concept of digital life skills in two school subjects. Our findings indicate that the teachers relate to digital life skills and consider them important. The teachers connect digital life skills to three themes we have labelled digital detox, digital footprints and digital responsibility. This study presents pedagogical and didactical implications of teachers’ perceptions and integration of digital life skills into their instructional practices. Furthermore, the findings provide valuable insights for policymakers and school leaders, enhancing their understanding of how upper secondary teachers in English and social science in Norway conceptualise digital life skills.

Keywords: digital life skills, digital detox, digital footprints, digital responsibility, teacher perceptions

Introduction

Concern for young people’s life skills and digital competence is a part of the public debate regarding the potential links between social media, increased screentime and mental health issues (NOU 2024: 20). This concern underscores the important role schools play in providing young people with the digital life skills necessary to successfully navigate in an increasingly complex digital landscape within and beyond the classroom. Digital life skills pertain to young people’s physical and mental health in interaction with digital technology, encompassing the relational aspects of their digital lives and how they navigate digital platforms (Gudmundsdottir, Brevik et al., 2024). Furthermore, digitalisation significantly influences students’ learning experiences, providing new opportunities while presenting several challenges (Gudmundsdottir, Holmarsdottir et al., 2024; Haleem et al., 2022; Timotheou et al., 2023).

Tackling such challenges necessitates an educational approach that prepares young people for both present life circumstances and future career opportunities (Ottestad & Gudmundsdottir, 2018). The significance of digital life skills impacts learning environments and well-being in school. Acquiring relevant skills and competences to manage their digital lives is vital for young people’s readiness for future challenges. Moreover, digital competence opens opportunities for social engagement and professional growth (Vissenberg et al., 2022), thereby making the mastery of digital competence an essential aim in the teaching of life skills. It is crucial to explore teachers’ perspectives on digital life skills in their teaching and the relationship between digital competence and life skills.

While studies have explored the relationship between social media and technology as it impacts life skills such as wellbeing and resilience as well as the ability to evaluate online risks (Ito et al., 2020; Livingstone et al., 2023), research exploring digital life skills from teachers’ perspectives is limited. Some studies have highlighted the need to address challenges and dynamics of the digital era when integrating technological skills into education (Hafina et al., 2024; Ilomäki et al., 2023; Ranta et al., 2022), and others have explored teachers’ perspectives on digital competence (Lindberg & Olofsson, 2018; Löfving, 2024), digital responsibility (Gudmundsdottir, Holmarsdottir et al., 2024) and life skills education (Ekornes & Øye, 2021; Rönnlund et al., 2019). Still, teachers’ voices must be heard more broadly surrounding life skills education (Isaksen et al., 2025). A recent report from Norway underscored this necessity for research on young people’s digital life skills (Gudmundsdottir, Brevik et al., 2024), making it critical to explore how teachers perceive and reflect on digital life skills within classroom settings across subjects and contexts. This exploration is important considering the recent curricular reform (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training [NDET], 2017a), which necessitates a deeper understanding of teachers’ insights and practices.

This study contributes to the conceptualisation of digital life skills. We compared the perceptions of teachers from both general and vocational study programmes to capture possible distinctions. Research on digitalisation in upper secondary education (Cattaneo et al., 2025) and vocational education contexts (Asplund & Kontio, 2020; Carlsson & Willermark, 2023; 2025) is scarce. Given the increasing number of applicants to vocational education (Kunnskapsdepartementet, 2025), research comparing study programmes is of particular interest. We selected the subjects English and social science for comparison due to their pivotal roles in the curriculum covering central areas of life skills education, along with their characteristics of preparing students to go out into society and the digital world. Although English and social science curricula share similarities and overlapping themes, they address life skills and digital competence differently (NDET, 2019a; 2019b). Comparing these subjects offers insights into preparing young people for their future academic, professional and personal lives. The following research question guided this study:

In the following sections, we unfold digital life skills as an evolving concept, drawing on existing research. We further unpack the concept of digital life skills as a synthesis of life skills education, digital competence and digital responsibility. Next, we outline the Norwegian educational context and digital life skills within the curriculum before presenting the methodology employed in this study. Finally, we present and discuss our findings.

Digital life skills: An evolving concept

We underscored digital life skills as a critical area of enquiry, particularly in relation to the challenges young people face when using digital technologies. To contribute to the conceptualisation of the concept, we conducted a targeted search of relevant literature according to the search criteria outlined below.

Through a wide search of literature, we present a selection of relevant studies on the teaching of digital life skills. We included the studies presented in the previous sections because their study concepts related to the context of “school”, “education*”, “teacher*”, “teach*”, “student*” and/or “pupil*”. Our initial criteria centred on the keywords “digital life skill*”, “digital life-skill*”, “digital well-being*” and/or “digital wellbeing*”. We also included previous literature that emphasised “life skills*” and/or “wellbeing*” (e.g. resilience, coping behaviours, wellness, mental health) interconnected with the “digital*” context (e.g. online, social media, technology).

One of the earliest studies mentioning digital life skills within an educational context originated in South Africa. This study examined mobile phone use to support students’ active participation within society (Botha & Ford, 2008). Botha and Ford (2008) highlighted developing life skills in the curriculum as necessary in a digital world. The importance of being an active participant in society and possessing critical awareness of information can thus be connected to teaching digital life skills. Dolanbay (2022) reinforced this connection and identified critical approaches to technologies as life skills, as technology influences how young people interact with the world and one another. Viewing how young people engage actively in the political, economic and socio-cultural dimensions of society, Boonlab and Pasitpakakul (2023) underscored the need to enhance young people’s abilities and strategies to protect themselves from online threats, develop crucial ethical values and understand rights and responsibilities. Other studies highlighted how young people’s digital lives can be viewed as an ecosystem of school, leisure time, family life and civic participation (Holmarsdottir et al., 2024), where online interactions may positively affect wellbeing, identity formation and sense of belonging (Gudmundsdottir, Holmarsdottir et al., 2024).

Researchers have raised concerns regarding the potential impacts and consequences of technology use within education. Livingstone et al. (2023) revealed that two-thirds of the studies included in their review were associated with online opportunities or benefits, while one-third explored online risks or harm. Livingstone et al. (2023) called for education “to build children’s resilience to mitigate online or offline vulnerability to risks of harm, as well as to encourage their coping behaviours” (p. 1188). Conversely, a review study by Ilomäki et al. (2023) identified key elements relevant for school and found a strong emphasis on internet safety in the included articles, which explored issues such as cyberbullying, sexual harassment and internet addiction. A less frequent dimension was digital wellbeing, which was previously explored in studies on e-safety, cyber wellness and cyberbullying. The study findings highlighted managing one’s own and others’ digital identities as important social skills that are rarely addressed in school (Ilomäki et al., 2023).

Schools, especially teachers, play a crucial role in developing young people’s digital life skills, both in general and subject-specific contexts (Gudmundsdottir, Brevik et al., 2024; Munthe et al., 2022). In their research on children’s well-being in a digital world, Smahel et al. (2020) called for a comparative approach. A recent report recommended shifting focus towards educating young people about technology rather than imposing bans, as young people’s wellbeing is affected by digital technology (Smahel et al., 2025). In the Norwegian context, a report evaluating the recent curriculum reform introduced the concept of digital life skills; however, this topic has yet to receive significant emphasis in research (Brevik et al., 2023).

Unpacking digital life skills

In this section, we examine digital life skills as the synthesis of three concepts: life skills education, digital competence and digital responsibility. Prior international research on life skills has emphasised the importance of addressing the challenges and dynamics of the digital era due to globalisation and societal shifts (Hafina et al., 2024; World Health Organization [WHO], 2020). Assisting children and young people to overcome challenges and develop into robust individuals are key goals of including life skills in education (WHO, 2020). Internationally, life skills are associated with concepts such as wellbeing, resilience, socio-emotional learning and 21st century skills (Brevik et al., 2023; Dey et al., 2022; Murphy-Graham & Cohen, 2022). The WHO (2020) recommended implementing life skills education as a pedagogical intervention, and it is implemented through intervention programmes (Cassidy et al., 2018), as separate school subjects (Jónasson et al., 2021) or embedded into existing school subjects (Brevik et al., 2023; Isaksen et al., 2025). A recent Norwegian study highlighted the importance of examining the digital lives young people encounter when facing challenges and mastering their lives (Isaksen et al., 2025). Hafina et al. (2024) stated that “supporting the future readiness of teachers to teach life skills with an emphasis on digitalisation is essential, covering skills related to work, entrepreneurship, and financial literacy” (p. 487). Thus, the digital context exerts a significant influence on many areas with relevance to life skills.

Next, digital competence is both a broad and a complex construct (Nagel et al., 2023; Pettersson, 2017) combining knowledge, skills and attitudes (Gudmundsdottir, Brevik et al., 2024). Various concepts may describe digital competence, such as competence and literacy (Godhe, 2019), using different prefixes (digital, information, media, etc.) or subdimensions (data, online, etc.) to reveal variation in approach (Ilomäki et al., 2023). In the following, we use digital competence to refer to students’ skills or actions (what they do), knowledge (what they understand) and interactions (their attitudes).

The third concept focuses on the connection between legal, ethical and attitudinal aspects of digital competence, which are imperative to strengthen digital responsibility (Gudmundsdottir, Holmarsdottir et al., 2024). In Norway, digital responsibility concerns acquiring knowledge and developing good strategies online (NDET, 2017b). This includes themes such as respecting copyright (Livingstone et al., 2015), interacting online, developing an online identity related to bullying and harassment (Flanagin & Metzger, 2008) and respecting the privacy of oneself and others online (Chang, 2021). In addition, strengthening the theoretical construct of digital responsibility in practice in school settings equips students with skills and attitudes to be responsible users on digital platforms (Gudmundsdottir, Holmarsdottir et al., 2024). When comparing digital responsibility across countries, Gudmundsdottir, Holmarsdottir et al. (2024) recognised the importance of raising digitally responsible students and supporting teachers in an increasingly globalised and networked society. Our aim is to investigate digital life skills in the Norwegian educational context, where teachers are expected to introduce life skills, digital competence and digital responsibility into their teaching, as outlined in the recent curriculum reform (NDET, 2017a).

Digital life skills in the Norwegian context

Norway’s national curriculum (LK20) requires that all three concepts be incorporated into all subjects (NDET, 2017a). Additionally, teachers can decide how to address these topics in their teaching practices. Consequently, it is the teacher who determines how and the extent to which life skills, digital competence and digital responsibility are integrated into teaching. This gives teachers a didactical choice in how to work with digital life skills in their classrooms.

In Norway, all children undergo 10 years of compulsory education, covering primary school (Years 1–7, ages 6–13) and lower secondary school (Years 8–10, ages 13–16). Students may then complete three or four years of upper secondary education (Years 11–14) in either general- or vocational-oriented study programmes. In vocational programmes, teachers in common core subjects like social science and English must apply a vocational orientation in addition to learning outcomes and competence aims required of both general and vocational programmes (Skarpaas, 2023).

English is taught in Year 11 for both programmes, while social science is taught in Year 11 or 12, depending on the study programme and school. English as a language subject is linked to life skills as foundational for communication, critical thinking and intercultural competence (NDET, 2019a). Conversely, social science provides essential insights into societal participation, including socialisation, digital citizenship and the necessary skills to participate in society (NDET, 2019b). By comparing perceptions from teachers in these subjects and across study programmes, we aim to explore how they reflect on digital life skills in their teaching and, consequently, prepare their students to develop digital life skills.

Methodology

This study was part of the longitudinal research project, EDUCATE (Evaluation of the new curriculum reform), which was conducted to evaluate the implementation of Norway’s LK20 curricular reform (Brevik et al., 2023). We used a qualitative design based on semi-structured teacher interviews. The interviews were conducted during the 2021–23 school years, following video observations of four consecutive lessons of naturally occurring classroom teaching, which was part of the EDUCATE project’s research design. The interviews concerned the teaching observed and recorded the teachers’ perceptions and reflections regarding life skills, digital competence and digital responsibility, as well as their teaching practices related to these topics.

Sample

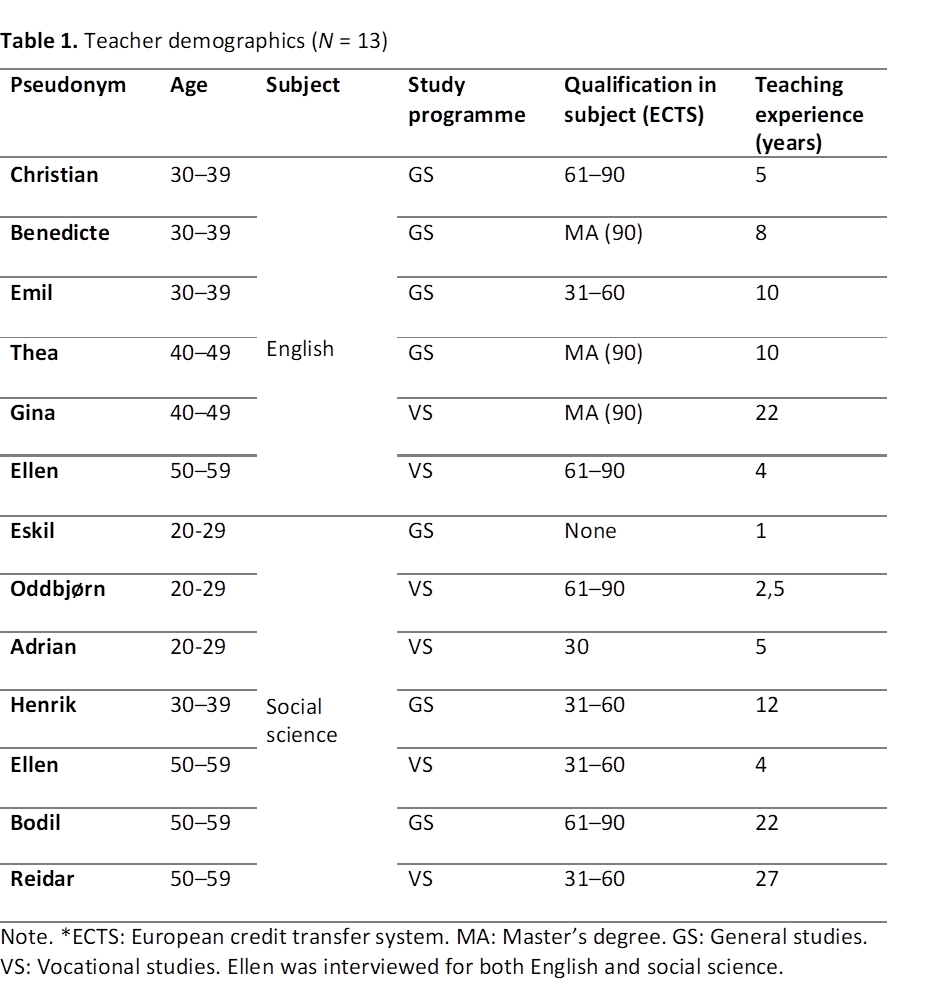

The study sample comprised teacher interviews that were conducted after video observations were collected in the EDUCATE project. Teachers participating in the EDUCATE project were strategically sampled from three upper secondary schools in urban and rural areas of Norway. Two schools contributed to both English and social science classes, whereas one school only participated in social science classes. This study included all interviewed teachers (N = 13) of English (n = 6) and social science (n = 7) in upper secondary study general (n = 7) and vocational (n = 6) programmes. The project’s overarching sampling strategy ensured a diverse representation regarding gender, age, formal education and teaching experience. Table 1 presents an overview.

Data collection: Teacher interviews

The interviews followed a semi-structured interview guide with possible follow-up questions. We focused on the parts of the interview guide that concerned teachers’ reflections on the concepts ‘life skills’, ‘digital competence’ and ‘digital responsibility’. The interview questions addressed what the teachers planned to teach, what they taught and their reflections on the topics. The interview guide was not designed to capture digital life skills but focused on life skills in general, digital competence and digital responsibility. All interviews were conducted in Norwegian and lasted approximately one hour. The interviews were audio-recorded with two recorders and manually transcribed using f4transcript. Finally, we listened to the audio-recorded interviews while reading the transcripts to ensure the quality and precision of the transcriptions.

Data analysis

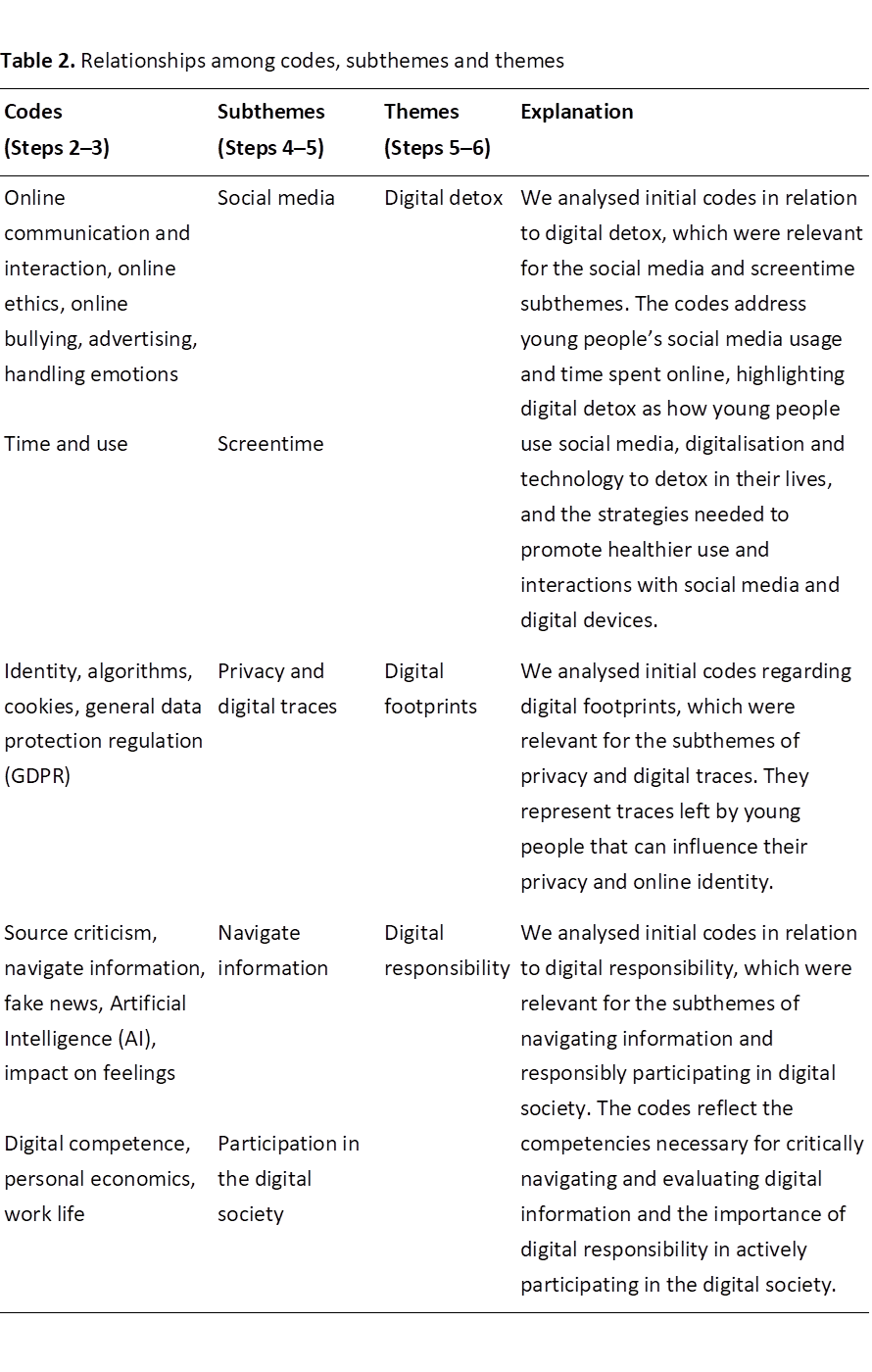

To analyse the 13 teacher interviews, we conducted six steps of reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2022) using deductive and inductive approaches to reveal teacher perceptions on digital life skills. First, Isaksen established familiarisation with the interviews by transcribing and noting first impressions of patterns while reading through the interviews (Step 1). Then, Isaksen analysed the interviews inductively through a manual coding procedure to establish initial codes (Step 2). Consequently, we used NVivo14 to systematically analyse and capture the nuances of the teacher interviews (Step 3). When passages showed relevance to the research question, they were summarised with a code based on previous steps. Segments in teacher reflections identified across interviews and connected to digital life skills revealed multiple codes. During this process, both authors discussed the codes in relation to the research question and the data material. In cases of uncertainty, Gudmundsdottir reviewed the data material to reach agreement with Isaksen in the coding. We sorted the codes into overarching themes and related subthemes by refining and reviewing each theme and adding descriptions to each subtheme (Steps 4–5). Finally, we interpreted themes and subthemes and identified relevant excerpts representing the emerging themes to illustrate the findings. The excerpts cited in this article were translated into English during the writing of the findings (Step 6). Table 2 provides a detailed coding scheme that presents the relationship between codes, subthemes and themes derived through the six steps of reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2022).

Research credibility, ethics and limitations

This study is covered by ethical approval through the EDUCATE project, from the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (Sikt). The participants provided written informed consent, which was stored on a secure server for sensitive data. To preserve teachers’ privacy and ensure their continued consent, participants were asked at the beginning of each interview to consent to the interviews being audio-recorded. The schools and classes were anonymised, and we used pseudonyms for the teachers.

For validity purposes, Isaksen and Gudmundsdottir discussed and validated themes and subthemes in several phases through peer debriefing (Tashakkori et al., 2020). Additionally, coding was conducted manually to become familiar with the data and recoded systematically through NVivo14 to validate and adjust prior codes and themes. The sample size was relatively small, limiting generalisability. However, as this study explores teachers’ perceptions of digital life skills across two subjects and study programmes, we argue that the design provides valuable insights that can be transferable to other samples and contexts. Readers can apply the research conclusions to similar situations by comparing their own educational contexts with those of the study (Johnson & Christensen, 2020) to make naturalistic generalisations. This process allows them to reflect upon the applicability of the study’s findings and to decide upon inference transferability (Tashakkori et al., 2020). Furthermore, analytic generalisations can be made by linking the findings to existing literature to identify overlaps and gaps (Yin, 2013).

Results

In the following section, we present findings related to teachers’ perspectives on digital life skills in English and social science teaching across study programmes. In doing so, we aim to highlight the practical applications and challenges educators encounter when working with digital life skills in their teaching. We identified three main themes through our reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2022): digital detox, digital footprints and digital responsibility (see Table 2). We present and discuss each in subsequent sections.

Digital detox

The first theme that is highly related to students’ digital life skills is what we call digital detox. This topic typically emerged when the teachers emphasised students’ social media use and screentime. All the teachers connected digital life skills to students’ social media use. In both subjects and study programmes, several teachers reflected on students’ communication and interactions on social media. Teachers mentioned TikTok, Snapchat and Instagram as information sources, and Eskil highlighted that social media is about “how different actors express themselves and how they use freedom of expression, especially on digital and social media”. He emphasised the importance of classroom conversations for students to reflect on social media’s significance in their lives.

We observed that when reflecting on students’ online communication, teachers often included topics related to subject-specific curricula. They emphasised the impact of social media and influencers when reflecting on students’ digital life skills. Socialising (NDET, 2019b) and interaction (NDET, 2019a) are part of the competency aims connected to life skills education in both subject curricula. Reidar connected socialising through social media with digital development. He explained:

how certain individuals suddenly become part of young people’s everyday lives though the digital…. We have talked a bit about influencers and those kinds of things as part of socialisation. But also, when I was preparing to start as a social science teacher in the autumn and had a department meeting and I did not know who Andrew Tate was, I was clearly told that I needed to know if I was going to be here. […] This is where digital responsibility comes in, I would say, how a person can gain such a position (Reidar, social science, vocational studies).

Interestingly, although all teachers mentioned social media during their interviews, the vocational study programme teachers placed notably greater emphasis on social media than teachers in general studies. In fact, Ellen and Gina, who taught English in vocational studies, paid the greatest attention to online ethics, with a focus on developing healthy digital manners. Gina referred to the potential challenges that:

arise when students produce videos without thinking critically. When they do not consider the consequences, what it can lead to later in life, what they are creating now. They need to take it seriously; they must think about internet safety (Gina, English, vocational studies).

Several teachers across subjects and study programmes also discussed online ethics and sharing pictures without consent as an important part of digital life skills. As teachers address these digital interactions, the concept of digital detox becomes relevant, highlighting the need to occasionally disengage from digital environments to foster mental well-being and physical interactions. The teachers discussed the need for students to understand internet safety in relation to legal matters and the consequences of spreading pictures online, necessitating digital detox to accept responsibility for their online practices. Furthermore, five teachers mentioned cyberbullying. Adrian said, “There is a lot of bullying that can happen digitally, or harassment, or sensitive images that should not be leaked. There is a lot to address there [in the classroom]”. Ellen further noted the importance of thematising and focusing on bullying and exclusion in relation to life skills implementation in the curricula:

As a teacher, you don’t stand a chance of salvaging situations that happen, and the hurtful incidents, the terrible things that some people experience when they are at home and see that everyone else in the group is out doing something together, and you weren’t invited (Ellen, social science, vocational studies).

Ellen’s connection between online bullying and life skills enhances the importance of integrating digital life skills as part of teaching young people to detox from harmful situations and fostering healthier relationships with technology and social media.

Furthermore, the handling of emotions was linked to mental health and stress-related topics. Thea mentioned “Adventures with Anxiety”, an interactive computer game that she included in general studies English that brought up topics such as anxiety “but also how society deals with it, what is a taboo and what is not”. She noticed that many students made their responses to game tasks very personal and wrote about their own struggles or friends who had issues. Thea connected the game directly to life skills and said that she tried “to make the teaching and the experience personal, because [she] got an impression that it sticks better, goes in more easily, and stays much longer” when thematising life skills through a digital game.

Furthermore, all the teachers had clear opinions on the students’ usage of screens inside and outside the classroom. They expressed the need for student awareness regarding screentime, which was explicitly connected to life skills. Henrik explained how important it is “that the students reflect upon and are aware of it. I think that awareness benefits public health and life skills”. The teachers showed a mutual understanding of screen use as a “source of distraction” (Adrian and Thea). Thea explained that the students “let themselves be distracted, they do not get started with the [school] work […], so it is not very surprising that they sometimes drift a bit and wonder where they are headed”.

Although the teachers taught in technology-savvy classrooms, several emphasised that not all lessons should include digital technology use and noted the importance of variation in teaching methods and student motivation. Benedicte stated:

I am kind of analogue in a way, so I try to balance it [the use of digital tools] a bit. Digital tools are not alpha and omega. I think it also relates a bit to life skills, using them where it is appropriate and employing other methods when they are more suitable (Benedicte, English, general studies).

Benedicte described the need for teachers to evaluate and make a conscious choice of when to use digital technology and for what purpose, relating to our conceptualisation of digital detox.

Although the teachers experienced challenges with the students’ use of digital technology, Henrik also expressed appreciation for the opportunities technology gave him as a teacher and worried about these being lost if he did not have the ability to utilise technology.

Digital detox is thus a central theme in digital life skills, as teachers reflected upon students’ use of digital devices and social media as a detox from and in life, with the need for strategies to advocate healthier use and interactions with social media and digital devices.

Digital footprints

The second theme linked to students’ digital life skills was digital footprints, mentioned by 10 teachers who frequently talked about digital traces and privacy. Identity was linked to digital footprints in all subjects across the study programme during the teacher interviews. Teachers connected identity to how the internet and social media impact privacy, online identity and students’ feelings, which relates to digital life skills. Gina said that she often talked to students about considering privacy issues and their digital footprints whenever they used the internet. She stated the need for students to understand “that everything that is published, everything that you have online is the digital footprint and ‘dust’ that you leave behind. It is used against you” (Gina, English, vocational studies).

Benedicte also connected students’ digital footprints to the need for them to understand their online identities. When discussing the impacts of influencers, she discussed the relevance of the study programme by connecting identity to English teaching in her vocational class. She expressed:

General studies do not have vocational orientation in the same way as health [the vocational programme: Healthcare, childhood and youth development], and in health when you teach vocational orientation [in English], it is very much health-related topics that by coincidence fit nicely with life skills. Topics like identity and some of these themes about finding oneself, being secure in who you are and such things. While in academic specialisation [general studies], we don’t necessarily get that type of balance (Benedicte, English, vocational studies).

By connecting online identity in English teaching in vocational studies to life skills, Benedicte emphasised digital life skills in her responses. Additionally, teachers in social science in vocational study programmes (Oddbjørn and Reidar) highlighted the importance of identity as a subject-specific topic. Oddbjørn said, “We had a period that we called ‘identity and life skills’ earlier this year when we worked with socialising […] how one becomes who they are, a bit more specifically”.

Moreover, several teachers discussed algorithms and general data protection regulation (GDPR) in connection to digital footprints. They addressed these issues in relation to developing student awareness and developing critical thinkers, thus linked to digital life skills. Ellen created connections between algorithms and life skills, as described below:

We work quite a bit with this in English, that algorithms control the information you receive, and what you are interested in determines what you get. On the one hand, they know this, but then they forget it. Adults forget it, too. So, I think it is becoming more important part of life skills, and ensures that they know what is true and what is not and how to distinguish between the two (Ellen, English, vocational studies).

Several teachers also talked about GDPR in relation to privacy and digital technology use inside the classroom. They emphasised the need to protect students’ privacy due to the storage of personal information. For example, English teacher Emil said that not all students want to publish their student work publicly on YouTube.

Therefore, digital footprints are an important theme for digital life skills, as they underscore the impact digital traces may have on privacy and students’ identity.

Digital responsibility

The final theme identified in teachers’ perceptions related to digital life skills was digital responsibility, which covers the ability to navigate information and participate in the digital society. All the teachers reflected on the importance of navigating information. The teachers directly connected source criticism to life skills by highlighting the connections between the concepts. Benedicte said, “I think source criticism is an important part of life skills, navigating the tangle of information they constantly have access to”. Oddbjørn also noted that “being able to navigate the big, bad world, especially the digital world, is quite essential to be able to manage well in the future”. Further reflections about conspiracy theories in relation to life skills and the importance of students’ ability to think critically were prominent in Oddbjørn’s interview.

Teachers unanimously emphasised the key role of students’ ability to evaluate the credibility of online information and thus the need to foster students’ digital responsibility. They connected the use of sources and the application of critical thinking to collective development and growth, which are important for being part of society (Gina). In addition, teachers discussed life skills as the individual impact on how students overcome fear in relation to Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine and deal with other challenging situations such as “crises, war, state of emergency, poverty, natural disasters, the list is endless, and they are in it twenty-four-seven” (Thea). Adrian also addressed digital life skills when he stated that understanding other people’s situations is part of life skills.

When asked to reflect on their students’ digital competence, several teachers connected it directly to the students’ life skills. All the teachers shared views on how students’ digital competence relates to being able to navigate in digital society and everyday life. Oddbjørn said that developing this competence meant “mastering life, that you are able to navigate the new world we are in now”. Henrik mused, “I think about digital competence as everyday digital competence. What helps me solve tasks?” Some teachers connected their students’ digital competence directly to their subject teaching, as language is an important factor in being able to navigate digitally. Thea said:

English is about becoming a strong and competent language user. Clearly, you cannot achieve that in today’s society and world if you do not also master the digital landscape and the range of digital tools and opportunities in English (Thea, English, general studies).

Another link to digital responsibility was how teachers taught personal economics, a topic directly related to life skills that was frequently mentioned by the social science teachers and taught in both study programmes. However, the general studies teachers included it more frequently. The social science teachers focused on personal economics by working with topics such as making a budget, saving money, understanding taxes and completing tax returns. These tasks rely on navigating various digital technologies and websites, such as calculators and Excel. The ability to navigate is thus relevant for digital responsibility to participate in society. Adrian pointed out that he “sees life skills in almost everything here at the school”. He continued:

I remember that in the past, there was not much focus on this in social science [prior to the curriculum reform]. But now we […] let the students create budgets and learn how to get a mortgage. Many were surprised to find that student loans are subtracted [when applying for a mortgage], and if you have children and things like that, it becomes quite challenging to enter the housing market (Adrian, social science, general studies).

Adrian’s reflections focused on students’ practical work and how personal economy was relevant to students’ digital life skills.

The teachers also connected students’ participation in digital society to work life in relation to digital life skills. Gina, an English teacher in vocational programmes, said it was important for the teacher to “look [at] what is new [in technology] and how to participate in working life, and bring it into the classroom”. She further connected digital technology to life skills:

I want them to create different media products, either podcasts, videos or posters […] because this is part of what they are going to do in their work life [students in technology class], and that is kind of life skills (Gina, English, vocational studies).

Ellen, another teacher in vocational programmes, highlighted the connection between digital competence, language use in English and working life. She explained, “They need to access YouTube to see work-related tasks. There is a lot to watch from carpenters setting up things, how to build things, what kind of tools you should bring, and everything is in English”. Ellen’s observation of internet usage to help with students’ work-related tasks is related to the importance of being able to navigate the digital world by using English. Therefore, the teachers highlighted students’ digital competence as important for digital life skills and conducting future professional tasks.

The teachers perceived digital responsibility as an important theme for digital life skills. Based on the teaching subject and study path, we found that teachers connected students’ ability to navigate information to digital life skills. They also emphasised participation in society across subjects and study paths. Furthermore, the teachers in vocational programmes used concrete examples more often directed towards the students’ future professions and working life, often connected to being able to navigate on digital platforms, which often are in English.

Linking teacher insights to the teaching of digital life skills provides an opportunity to evaluate teachers’ perceptions of digital life skills within the context of the LK20 curricular reform. We found that the teachers addressed digital detox, digital footprints and digital responsibility through various approaches when they discussed aspects related to digital life skills in the interviews. In the subsequent section, we discuss these findings and examine how they answered our research question.

Discussion

We examined how teachers perceived digital life skills in teaching in upper secondary schools as a response to a new educational reform (NDET, 2017a). In general, the teachers in English and social science classes in general and vocational study programmes perceived digital life skills as a variety of themes that assist students in coping online with various aspects of their lives, which aligns with previous research (Holmarsdottir et al., 2024; Livingstone et al., 2023). The concept of digital life skills, as analysed from teacher interviews, encompasses the following themes: digital detox, digital footprints and digital responsibility. Considering teacher perceptions, digital life skills are increasingly important for students to navigate, communicate and act responsibly in their (digital) lives. Incorporating such themes into teaching better prepares students for academic, personal and future professional challenges, consistent with existing studies (Hafina et al., 2024; Ranta et al., 2022; Vissenberg et al., 2022). Some overlap and intersection between themes are unavoidable because of their interconnected nature. For example, digital responsibility inherently involves understanding digital footprints, as responsible online behaviour requires awareness of the traces one leaves behind online. This natural intersection reinforces the importance of a comprehensive approach to teaching digital life skills, as well as the need for further research.

The teachers highlighted digital responsibility as fundamental in students’ understanding of the credibility of online information, including fake news, conspiracy theories and their participation in society. Prior studies have similarly found a critical approach to technology and online information connected to digital life skills (Dolanbay, 2022; Gudmundsdottir, Holmarsdottir et al., 2024; WHO, 2020). The importance attributed to digital competence and the practical implications suggest that teachers recognise the growing influence of social media on their students’ lives. In addition, teachers’ responses reveal that they see themselves as responsible for equipping students with the tools necessary to handle digital content critically and responsibly while preserving students’ online identity and privacy, linking digital life skills to the theme of digital footprints. Previous literature related to digital life skills has featured young people’s development of online identity (Flanagin & Metzger, 2008; Gudmundsdottir, Holmarsdottir, et al., 2024) and internet safety (Boonlab & Pasitpakakul, 2023; Chang, 2021; Ilomäki et al., 2023). This conceptualisation aligns with the broader educational goal of fostering informed, reflective and responsible citizens who can contribute positively to society (Boonlab & Pasitpakakul, 2023; Botha & Ford, 2008; Holmarsdottir et al., 2024; Livingstone et al., 2023), as emphasised in the Norwegian national curriculum (NDET, 2017a).

We identified notable differences in how English and social science teachers perceived and applied digital life skills in their teaching. We acknowledge that these differences are connected to different aspects of the curriculum (NDET, 2017a). English teachers tended to integrate digital competence by emphasising the need for students to become competent language users according to the English subject curriculum (NDET, 2019a). They highlighted activities like participating in digital conversations and understanding the impact of digital footprints and digital detox. Related research has underscored online interactions as imperative for digital life skills (Flanagin & Metzger, 2008). However, prior research has connected online communication to the enhancement of relationships and improving mental health and well-being (Gudmundsdottir, Holmarsdottir et al., 2024; Ito et al., 2020; Livingstone et al., 2023; Vissenberg et al., 2022) rather than educating competent language users, which our findings suggest.

Taking a different approach, social science teachers unsurprisingly focused more on the societal implications of digital life skills through students’ digital responsibilities. This focus is connected to topics such as understanding personal economics, navigating information and critically engaging with social media, which aligns with the subject curriculum (NDET, 2019b). Social science teachers underscored the importance of students being able to use digital technology to stay informed (Boonlab & Pasitpakakul, 2023; Botha & Ford, 2008; Ito et al., 2020), as well as the impact of influencers and media, which previous research has indicated impacts relationships and wellbeing (Ito et al., 2020).

Although teachers across general and vocational study programmes emphasised similar patterns in digital life skills, our findings revealed a difference in how they perceived digital life skills. General studies teachers placed more emphasis on broader digital competence applicable across various contexts, such as critical thinking, source evaluation and personal economy, identified as life skills in the curricula (NDET, 2017a; 2019b). They aim to prepare students for a wide range of future academic and professional paths. Conversely, vocational studies teachers were likelier to provide specific examples related to students’ future professions. They focused on practical applications of digital technology that were directly relevant to work assignments, such as the need to use English to navigate and conduct work-related tasks. This focus is supported by the literature indicating the importance of the necessary competences related to work and future life (Hafina et al., 2024; Ottestad & Gudmundsdottir, 2018).

Teachers also emphasised digital detox, particularly regarding social media and online interactions, as relevant to advocating healthier technology use. Teachers perceive digital devices as a “source of distraction” and highlight a need for young people to detox from harmful situations, such as cyberbullying, in line with the debate around increased screentime and mental health issues (NOU 2024: 20). Digital detox focuses primarily on young people’s awareness of and need for strategies in knowing when and how to use digital technology and social media. Implications for teachers may be in line with Smahel et al.’s (2025) recommendation of shifting focus towards educating young people instead of banning technology. Similarly, studies have highlighted the importance of developing online resilience (Livingstone et al., 2023; Vissenberg et al., 2022) and building strategies to protect themselves from online threats (Boonlab & Pasitpakakul, 2023). To the best of our knowledge, previous studies have not discussed these issues in relation to professional and academic life, which indicates a clear contribution of this study. The practical orientation of the vocational programmes is evident in how teachers connected digital life skills to industry-specific tasks and ethical considerations. This finding highlights the need for comparison across subjects and study programmes, as indicated in the literature (Asplund & Kontio, 2020; Carlsson & Willermark, 2023, 2025; Cattaneo et al., 2025). Such a comparison nuances the conceptualisation of teachers’ perceptions of digital life skills.

In conclusion, our findings suggest several implications for educational practice and future research. First, our findings may transfer to other subjects within language and social sciences and provide new perspectives on upper secondary education across general and vocational study programmes (Carlsson & Willermark, 2025; Cattaneo et al., 2025). Second, it is important to continue exploring how digital life skills are understood and implemented as a comparative approach across different subjects and educational contexts (Smahel et al., 2020). Such approaches can identify unique subject- and programme-related ways to integrate digital life skills into teaching. By exploring the distinctions, we gain a greater understanding of the definition and conceptualisation of digital life skills and the importance of teachers’ roles in developing young people’s digital life skills. It also enhances our understanding of the specific needs and challenges faced by teachers and students when approaching digital life skills across subject curricula.

By ensuring that digital life skills are adequately addressed across subjects and study programmes, we can better prepare students for their complex digital lives and future challenges (Holmarsdottir et al., 2024; Ottestad & Gudmundsdottir, 2018). The teacher perspectives presented in this study are important for understanding how they view real-world challenges in young people’s lives, as well as curricular implications of digital life skills in students’ education across subject and study orientations.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the schools and teachers who participated in this study. A special thanks goes to Professor Lisbeth M. Brevik and Associate Professor Nora E. H. Mathé for their valuable feedback in peer-reviewing our paper. Additionally, we would like to express our gratitude to all members of the EDUCATE research group for invaluable contributions throughout the research process.

Funding details

Isaksen was supported by the Research Council of Norway (Project Number 331135) and by Strømmen Upper secondary school. The EDUCATE project received support by the Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training.

References

Asplund, S.-B., & Kontio, J. (2020). Becoming a construction worker in the connected classroom: Opposing school work with smartphones as happy objects. Nordic Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 10(1), 65–94. https://doi.org/10.3384/njvet.2242-458X.2010165

Boonlab, S., & Pasitpakakul, P. (2023). Developing a teaching and learning model to foster digital citizenship in general education undergraduate courses. Journal of Social Studies Education Research, 14(3), 287–304. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/222943/

Botha, A., & Ford, M. (2008). “Digital life skills” for the young and mobile “digital citizens”. MLearn08 Conference. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4862.9846

, & (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage.

Brevik, L. M., Gudmundsdottir, G. B., Barreng, R. L. S., Dodou, K., Doetjes, G., Evertsen, I., Goldschmidt-Gjerløw, B., Hatlevik, O. E., Hartvigsen, K. M., Isaksen, A. R., Magnusson, C., Mathé, N. E. H., Siljan, H., Stovner, R. B., & Suhr, M. (2023). Å mestre livet i 8. klasse. Perspektiver på livsmestring i klasserommet i sju fag [To master life in Year 8. Perspectives on life skills in the classroom across seven subjects] (Rapport 2 fra forsknings- og evalueringsprosjektet EDUCATE ved Institutt for lærerutdanning og skoleforskning). Universitetet i Oslo. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.8012569

Carlsson, S., & Willermark, S. (2023). Teaching here and now but for the future: Vocational teachers’ perspective on teaching in flux. Vocations and Learning, 16(3), 443–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-023-09324-z

Carlsson, S., & Willermark, S. (2025). Who’s account(able)? Making sense of Instagram in vocational teaching practices. Nordic Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 15(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3384/njvet.2242-458X.251521

Cassidy, K., Franco, Y., & Meo, E. (2018). Preparation for adulthood: A teacher inquiry study for facilitating life skills in secondary education in the United States. Journal of Educational Issues, 4(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.5296/jei.v4i1.12471

Cattaneo, A., Schmitz, M. L., Gonon, P., Antonietti, C., Consoli, T., & Petko, D. (2025). The role of personal and contextual factors when investigating technology integration in general and vocational education. Computers in Human Behavior, 163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2024.108475

Chang, B. (2021). Student privacy issues in online learning environments. Distance Education, 42(1), 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2020.1869527

Dey, S., Patra, A., Giri, D., Varghese, L., & Idiculla, D. (2022). The status of life skill education in secondary schools. An evaluative study. Online International Interdisciplinary Research Journal, 12(1), 76–88.

Dolanbay, H. (2022). The experience of media literacy education of university students and the awareness they have gained: An action research. International Online Journal of Education and Teaching (IOJET), 9(4), 1614–1631. https://iojet.org/index.php/IOJET/article/view/1727

Ekornes, S., & Øye, R. (2021). Inter-professional collaboration for the promotion of public health and life skills in upper secondary school – A Norwegian case study. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 10(4), 527–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2021.1915216

Flanagin, A. J., & Metzger, M. (2008). Digital media and youth: Unparalleled opportunity and unprecedented responsibility. In M. J. Metzger & A. J. Flanagin (Eds.), Digital media, youth, and credibility (pp. 5–28). MIT Press.

Godhe, A. (2019). Digital literacies or digital competence: Conceptualizations in Nordic curricula. Media and Communication, 7(2), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v7i2.1888

Gudmundsdottir, G. B., Brevik, L. M., Aashamar, P. N., Barreng, R. L. S., Dodou, K., Doetjes, G., Hatlevik, O. E., Hartvigsen, K. M., Isaksen, A. R., Magnusson, C. G., Mathé, N. E. H., Roe, A., Skarpaas, K. G., Stovner, R. B., & Suhr, M. L. (2024). Å gi rom for variasjon og valgfrihet, mens vi venter på digital dømmekraft. Digital kompetanse i fagene i det heldigitale klasserommet på 10. trinn og Vg3 [Variation and freedom of choice, while we are waiting for digital responsibility. Digital competence in the subjects in the digital classroom in grade 10 and 13] (Rapport 4 fra forsknings- og evalueringsprosjektet EDUCATE ved Institutt for lærerutdanning og skoleforskning). Universitetet i Oslo.

Gudmundsdottir, G. B., Holmarsdottir, H., Mifsud, L., Teidla-Kunitsõn, G., Barbovschi, M., & Sisask, M. (2024). Talking about digital responsibility: Children’s and young people’s voices. In H. Holmarsdottir, I. Seland, C. Hyggen, & M. Roth (Eds.), Understanding the everyday digital lives of children and young people (pp. 379–431). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-46929-9_13

Hafina, A., Rusmana, N., Hamzah, R. M., Irawan, T. M. I. A., & Mulyati, S. (2024). Developing a model for life skills training through the enhancement of academic, personal, social, and career competencies for middle school students. Journal of Education and E-Learning Research, 11(3), 481–489. https://doi.org/10.20448/jeelr.v11i3.5847

Haleem, A., Javaid, M., Qadri, M. A., & Suman, R. (2022). Understanding the role of digital technologies in education: A review. Sustainable Operations and Computers, 3, 275–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susoc.2022.05.004

Holmarsdottir, H., Seland, I., Hyggen, C., & Roth, M. (Eds.) (2024). Understanding the everyday digital lives of children and young people. Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-46929-9

, , , , , , & (2023). Critical digital literacies at school level: A systematic review. Review of Education, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3425

Isaksen, A. R., Mathé, N. E. H., Brevik, L. M., & Gudmundsdottir, G. B. (2025). Life skills as a balancing act: Preparing students to handle life challenges in upper secondary English and social science classrooms. Teaching and Teacher Education, 159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2025.104992

Ito, M., Odgers, C., Schueller, S., Cabrera, J., Conaway, E., Cross, R., & Hernandez, M. (2020). Social media and youth wellbeing. What we know and where we could go. Connected Learning Alliance. https://clalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Social-Media-and-Youth-Wellbeing-Report.pdf

Johnson, R. B., & Christensen, L. B. (2020). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches (7th ed.). Sage.

Jónasson, J., Ragnarsdottir, G., & Bjarnadottir, V. (2021). The intricacies of educational development in Iceland: Stability or disruption? In J. Krejsler, & L. Moos (Eds.), What works in Nordic school policies? Mapping approaches to evidence, social technologies and transnational influences (pp. 67–86). Springer.

Kunnskapsdepartementet. (2025, March 20). Aldri før har flere søkt yrkesfag [Never before have more people applied for vocational education]. Regjeringen.no Pressemeldinger. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/aktuelt/aldri-for-har-flere-sokt-yrkesfag/id3092842/

Lindberg, J. O., & Olofsson, A. D. (2018). Recent trends in the digitalization of the Nordic K-12 schools. Seminar.net, 14(2), 103–108. https://doi.org/10.7577/seminar.2974

Livingstone, S., Mascheroni, G., & Staksrud, E. (2015). Developing a framework for researching children’s online risks and opportunities in Europe. EU Kids Online. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/64470/

Livingstone, S., Mascheroni, G., & Stoilova, M. (2023). The outcomes of gaining digital skills for young people’s lives and wellbeing: A systematic evidence review. New Media & Society, 25(5), 1176–1202. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211043189

Löfving, C. (2024). Teachers’ negotiation of the cross-curricular concept of student digital competence. Education and Information Technologies, 29(2), 1519–1538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11800-x

Munthe, E., Erstad, O., Njå, M. B., Forsström, S., Gilje, Ø., Amdam, S., Moltudal, S., & Hagen, S. B. (2022). Digitalisering i grunnopplæring; kunnskap, trender og framtidig forskningsbehov [Digitalisation in basic education: Knowledge, trends, and future research needs]. Kunnskapssenter for utdanning, Universitetet i Stavanger.

Murphy-Graham, E., & Cohen, A. (2022). Life skills education for youth in developing countries: What are they and why do they matter? In J. DeJaeghere & E. Murphy-Graham (Eds.), Life skills education for youth. Critical perspectives (pp. 13–41). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85214-6

Nagel, I., Gudmundsdottir, G. B., & Afdal, H. W. (2023). Teacher educators’ professional agency in facilitating professional digital competence. Teaching and Teacher Education, 132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104238

Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training (NDET). (2017a). Core curriculum – Values and principles for primary and secondary education. https://www.udir.no/lk20/overordnet-del/opplaringens-verdigrunnlag/?lang=eng

Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training (NDET). (2017b). Rammeverk for grunnleggende ferdigheter [Framework for basic skills]. https://www.udir.no/laring-og-trivsel/rammeverk/rammeverk-for-grunnleggende-ferdigheter/

Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training (NDET). (2019a). Curriculum in English (ENG01-04). The National Curriculum for the Knowledge Promotion 2020. https://www.udir.no/lk20/eng01-04?lang=eng

Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training (NDET). (2019b). Curriculum in social science (SAK01-01). The National Curriculum for the Knowledge Promotion 2020. https://www.udir.no/lk20/sak01-01?lang=eng

NOU 2024: 20. (2024). Det digitale (i) livet. Balansert oppvekst i skjermenes tid [The digital (in) life. A balanced upbringing in the era of screens]. Kunnskapsdepartementet. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/c252947398de4fb0aea9349f011eb410/no/pdfs/nou202420240020000dddpdfs.pdf

Ottestad, G., & Gudmundsdottir, G. B. (2018). Information and communication technology policy in primary and secondary education in Europe. In J. Voogt, G. Knezek, R. Christensen, & K.-W. Lai (Eds.), Second handbook of information technology in primary and secondary education (pp. 1343–1362). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71054-9_92

Pettersson, F. (2017). On the issues of digital competence in educational contexts – A review of literature. Education and Information Technologies, 23, 1005–1021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-017-9649-3

Ranta, M., Kruskopf, M., Kortesalmi, M., Kalmi, P., & Lonka, K. (2022). Entrepreneurship as a neglected pitfall in future Finnish teachers’ readiness to teach 21st century competencies and financial literacy: Expectancies, values, and capability. Education Sciences, 12(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12070463

Rönnlund, M., Ledman, K., Nylund, M., & Rosvall, P. (2019). Life skills for “real life”: How critical thinking is contextualised across vocational programmes. Educational Research, 61(3), 302–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2019.1633942

Skarpaas, K. G. (2023). The importance of relevance: Factors influencing upper secondary vocational students’ engagement in L2 English language teaching. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 68(7), 1395–1409. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2023.2250360

Smahel, D., Machackova, H., Mascheroni, G., Dedkova, L., Staksrud, E., Ólafsson, K., Livingstone, S., & Hasebrink, U. (2020). EU Kids Online 2020: Survey results from 19 countries. EU Kids Online. https://doi.org/10.21953/lse.47fdeqj01ofo

Smahel, D., Šaradín Lebedíková, M., Lacko, D., Kvardová, N., Mýlek, V., Tkaczyk, M., Svestkova, A., Gulec, H., Hrdina, M., Machackova, H., & Dedkova, L. (2025). Tech & teens: Insights from 15 studies on the impact of digital technology on well-being. EU Kids Online. https://doi.org/10.21953/lse.g4asyqkcrum7

Tashakkori, A., Johnson, R. B., & Teddlie, C. (2020). Foundations of mixed methods research. Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Sage.

Timotheou, S., Miliou, O., Dimitriadis, Y., Sobrino, S. V., Giannoutsou, N., Cachia, R., Monés, A. M., & Ioannou, A. (2023). Impacts of digital technologies on education and factors influencing schools’ digital capacity and transformation: A literature review. Education and Information Technologies, 28(6), 6695–6726. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11431-8

Vissenberg, J., d’Haenens, L., & Livingstone, S. (2022). Digital literacy and online resilience as facilitators of young people’s wellbeing? A systematic review. European Psychologist, 27(2), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000478

World Health Organization. (2020). Life skills education school handbook: Prevention of noncommunicable diseases. World Health Organization.

Yin, R. K. (2013). Validity and generalization in future case study evaluations. Evaluation, 19(3), 321–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389013497081