Vol 9, No 4 (2025)

https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.6182

Article

Comparing Teacher Attitudes Toward Early Grade Reading Reform in Northern and Central Uganda

Jonathan Marino

University of Wisconsin-Madison

Email: jmarino4@wisc.edu

Medadi E. Ssentanda

Makerere University/Stellenbosch University

Email: medadies@gmail.com

Abstract

Donors and policymakers across many countries are currently focused on improving early grade literacy outcomes through structured pedagogy reforms. This paper asks how teachers in three primary schools in two different linguistic settings of Uganda (Luganda and Acholi[1]) perceive and enact early grade reading reforms. Through interviews and classroom observations conducted from October 2022 to March 2023, the paper finds that teachers value and see the benefit of new reading instruction pedagogies and materials, but also identify key misalignments between curricular designs and their classroom and community realities, particularly in the areas of language standardization and examinations. To sustain new reading pedagogies, interventions must account for the cultural politics of pedagogy that shape teachers’ working conditions and decision-making.

Keywords: early literacy, curriculum reform, reading, teachers, Uganda

Introduction

While multiple competencies drive sustainable development, literacy (reading and writing) remains the indispensable foundation for all lifelong learning (Wagner, 2018). Given its critical role, literacy initiatives consistently attract significant attention from policymakers and bilateral and multilateral donor organizations. For example, in 2011 the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) announced an ambitious goal to “improve reading skills for 100 million children in primary grades” in more than 50 countries worldwide (Graham & Kelly, 2018). Donors and policymakers are focused on improving children’s reading outcomes through structured pedagogy initiatives that center the provision of books and materials to schools, scripted lessons and guides for teachers, and pre- and in-service teacher training aligned to new curricular materials that emphasize phonics-based approaches to reading instruction (Piper & Dubeck, 2024).

Given that teachers sit at the center of these donor-funded reforms, both as objects of reform and as subjects who shape their meaning and scope through implementation, “it is important that research tracks teachers’ responses to new demands” (Johnson et al., 2005, p. 64). This study, therefore, focuses on the case of Uganda, a country in which early grade reading reforms are taking place within a context of linguistic complexity, low-learner achievements in schools, teacher-centered challenges (e.g. high pupil-teacher ratios and un-even teacher training quality), and significant ongoing efforts to revitalize the use of children’s mother tongues in instruction.

Starting in 2011, a series of large-scale USAID-funded donor-funded early grade reading interventions began shifting how reading is taught and measured in Ugandan government primary schools. This paper builds on a limited research base that has investigated the impact of these early grade reading reforms in Uganda. Brunette et al. (2019) compared students’ Early Grade Reading Assessment (EGRA) scores across the twelve languages in which a new early grade reading curriculum, I Can Read and Write, was translated and found significant increases in reading scores in nine of the twelve languages. They also found language characteristics to be most predictive of reading gains, followed by socioeconomic factors and implementation fidelity. These findings track with the literature on structured reading pedagogy reforms globally, which suggests an overall positive impact on student outcomes (Stern & Piper, 2019; Evans & Mendez Acosta, 2020), but a leveling of gains over time (Piper & Dubeck, 2024).

In this paper, we build on Wenske and Ssentanda (2021) who conducted teacher interviews in two linguistic settings in Uganda – Ateso and Luganda – and found that teachers view the aforementioned I Can Read and Write reading curriculum and pedagogies as being ill-suited for Ugandan classroom realities. We replicate their work in a Luganda-dominant setting, and extend to a new linguistic setting, Acholi. By combining teacher interviews with classroom observations, we also triangulate teacher perceptions with enactments of reading instruction. Using a qualitative comparative case study method, therefore, this study asks:

1. How do Ugandan early primary teachers perceive and experience changes to the early grade reading curricula brought about by recent donor-funded programs?

2. How do teachers’ perceptions and experiences vary across two linguistic and regional settings in northern and central Uganda, respectively?

Context

Uganda became a site of early grade reading reform in 2011 when the Ugandan Ministry of Education and Sports (MoES), United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and non-governmental organizations, including Research Triangle Institute (RTI) and SIL, launched the School Health and Reading Program (SHRP) to improve reading outcomes for young children in primary grades 1-3. SHRP entailed several activities, including the introduction of a new reading curriculum, I Can Read and Write[2], distribution of textbooks to schools, and trainings for early primary school teachers. In 2015, USAID funded a second large-scale early grade reading initiative, the Literacy Achievement and Retention Activity (LARA), that expanded the reach of I Can Read and Write textbooks and curriculum materials into additional districts. The Uganda Teacher and School Effectiveness Project (UTSEP), funded by the Global Partnership for Education and the World Bank, also utilized materials developed under SHRP and expanded their reach further from 2015-2020. A fourth major early grade reading initiative, the Integrated Community and Youth Development Activity (IYCD), funded by USAID and launched in 2019, is now replenishing I Can Read and Write books in some districts and expanding teacher training methodologies into Uganda’s pre-service teacher training institutions. In total, these four initiatives have reached 9,000 primary schools in Uganda since 2012, covering over 80% of the country (Brunette et al., 2019).

Early grade reading reform took root in Uganda just after another major primary level curriculum overhaul, the Thematic Curriculum, was adopted in 2006 (Altinyelken, 2010). That reform emphasized the use of Ugandan languages for instruction in early primary grades, with a transition to English-based instruction starting at primary level 4. Uganda is a highly multilingual country, with more than forty languages spoken in Uganda (Simons & Fennig, 2019). The 2006 Thematic Curriculum also re-organized subject-matter competencies into twelve thematic areas, such as “our school,” “our community,” and “health and the human body”, designed to make learning more relevant and engaging for students (NCDC, 2016).

While the I Can Read and Write curriculum is aligned to the twelve themes specified in the Thematic Curriculum, it also introduced a new highly structured reading pedagogy that features a phonics-based approach to reading instruction. Prior to I Can Read and Write, a whole language rather than phonics-based approach to reading instruction was the norm in Ugandan primary school classrooms, and teachers designed their own lessons aligned to the Thematic Curriculum (Ssentanda & Wenske, 2023).

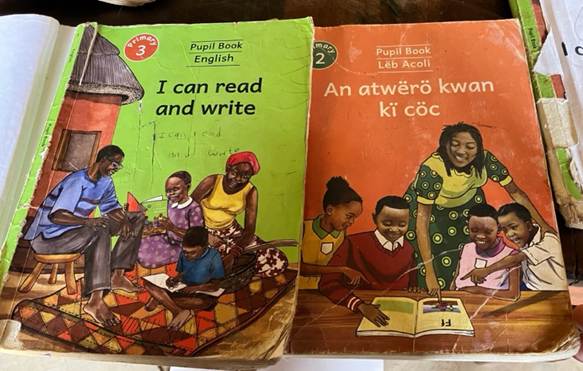

Figure 1. English and Acholi versions of I Can Read and Write/ An Atwëro Kwan kï Cöc pupil books in use in sample schools

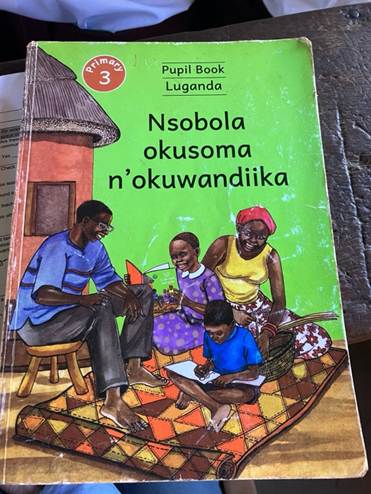

Figure 2. Luganda version of I Can Read and Write pupil book, Nsobola okusoma n’okuwandiika

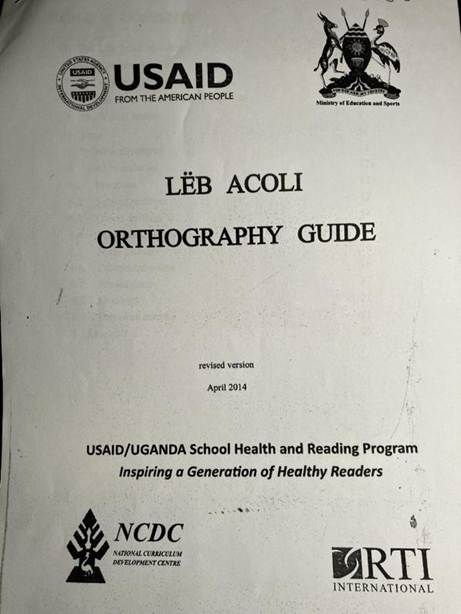

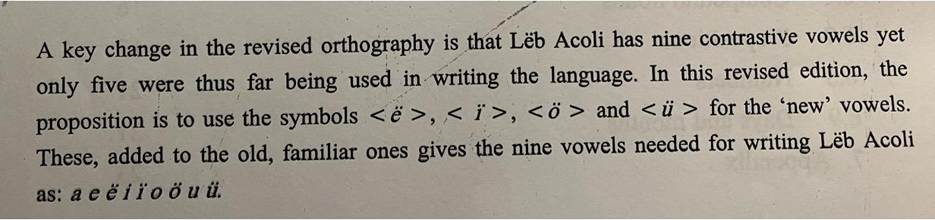

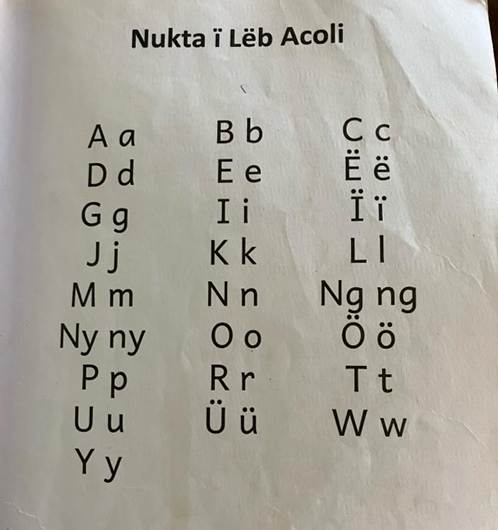

The language policy introduced as part of the 2006 Thematic Curriculum reform meant that the new I Can Read and Write curriculum had to be made available in a variety of Ugandan languages. This required curriculum designers to decide which languages would be utilized in the program, and which versions of these languages would be used, since in many Ugandan languages standardized orthographies had not been agreed to or established in print. To date, the I Can Read and Write curriculum has been translated into twelve Ugandan languages, with more translations planned. This process of establishing singular and standardized orthographies had different impacts on different languages. For example, in Luganda, the Ugandan language with the largest speaking population primarily located in southern Uganda around the capital Kampala, the new reading curriculum utilized existing orthography already in circulation in schools. In other languages, Language Boards were formed under the auspices of the Uganda National Curriculum Development Center (NCDC) to establish new alphabets not previously in use. This was the case in Ateso, a language spoken mainly in the eastern part of Uganda. There, four new vowels were added to the written Ateso alphabet as part of the process of translating I Can Read and Write into Ateso (Wenske & Ssentanda, 2021). This created difficulty for teachers and created gaps between language use in school and the outside: “There is a complete separation between the SHRP program – which is introducing the new orthography in schools – and the broader public sphere” (Wenske & Ssentanda, 2021, p. 10). Such extensive orthographic change was also seen in Acholi, a Luo variant primarily spoken in northern Uganda. An Acholi Language Board was also convened to define a writing system to guide the translation of I Can Read and Write from English into Acholi. This Language Board introduced a new orthography that included four new vowel symbols not previously in use. The purpose of these new vowels was to help readers differentiate between heavy and light vowel sounds.[3] The new Acholi orthography introduced the use of superscripts (two dots above a vowel, similar to an umlaut) to indicate a light pronunciation of the vowel. Figure 4 shows the cover page of this new orthography. Figure 5 is the description of these new written letters provided in the Acholi orthography produced under the SHRP program. Figure 6 shows the alphabet as printed within An Atwëro Kwan kï Cöc, the Acholi translation of the I Can Read and Write curriculum.

Figure 3. Acholi Orthography cover page

Figure 4. Acholi Orthography excerpt

Figure 5. Acholi Orthography alphabet

These orthography changes in Ateso, Acholi and other Ugandan languages show how early grade reading reform in Uganda did not just introduce new reading curricula but also shaped the structure of languages.

Theoretical Framework

To undertake our inquiry, we draw on policy enactment theory to focus on the ways teachers interpret and shape policy reforms as they “make sense of, mediate, struggle over, and sometimes ignore” new policy expectations and practices (Ball et al., 2012, p. 3). Policy enactment theory construes ‘policies’ not through their formal language in laws or statutes expressed in official channels, such as a legislative body or administrative agency, but through “the interaction and inter-connection between diverse actors, texts, talk, technology and objects (artifacts)” (Ball et al., 2012, p. 3). In this way, “Policy is not ‘done’ at one point in time; it is always a process of ‘becoming,’ changing from the outside in and the inside out. It is reviewed and revised as well as sometimes dispensed with or simply just forgotten” (Ball et al., 2012, p. 3). Teachers’ enactment of policy is shaped by the processes through which they come to learn about a policy’s purpose, expectations, and limits (Spillane et al., 2015). Cognitive and constructivist learning theories indicate that teachers do much more than merely ‘adopt’ and ‘implement’ fixed policy packages (Ertmer & Newby, 1993). Instead, they draw on their prior knowledge, peer networks, and their everyday experiences to make sense of a policy reform’s intent and implications.

Further, teachers’ sensemaking is shaped by the cultural politics of pedagogy, which Vavrus (2009) defines as the “broader economic and political dimensions of pedagogical theory and practice” (p. 305). In the Ugandan context, for example, a critical dimension shaping teacher instruction pertains to the linguistic environments within which instruction occurs. As previously mentioned, Uganda has experienced fluctuating language of instruction policies, with the most recent one adopted in 2006 (Altinyelken, 2010). At classroom level, however, teachers must go beyond the official formation and codification of policy to negotiate the linguistic realities present in their classrooms. These realities include the impact of migration on languages spoken by students, multilingual students’ blending and mixing of multiple languages in their speaking and writing, and parents, politicians and other local stakeholders who exert their own ideologies about which languages should be used for instruction. In recognition of this critical language context, our study centers teachers as language policymakers (McCarty & Warhol, 2011; Menken & Garcia, 2010). Drawing on these theoretical frames, therefore, we trace how teachers shape policy through practice, and how teachers’ policymaking power is situated within the social, cultural and political worlds they inhabit.

Methods

We use a comparative case study design to answer our questions regarding (1) teachers’ perceptions of an early grade reading reform and (2) variations in teacher perceptions across two regional and linguistic settings. The comparative case study (CCS) expands upon the traditional case study—where a single bounded place, community, or organization is studied – to compare enactments across sites, social scales, and over time (Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017). Our data for this research draws from a larger mixed methods and multi-sited research project that compares how different stakeholders, including international donors, non-governmental organization workers, national and regional-level policymakers, and teachers implement early grade reading reforms in Uganda. Here we focus just on teacher experiences using our qualitative data from three primary schools — one, Hillside Primary, located in Wakiso District and two, Garden Primary and Forest Primary, located in Gulu District. Adopting a comparative case approach makes it possible to contrast how a common curricular reform is perceived and implemented by teachers across different sites and settings (Yin, 2014). In our case, our comparative strategy focused on comparing teachers in schools in multiple linguistic and regional settings, based on our theoretical framing of the role of language and regional diversity in shaping teachers’ sensemaking about instruction.

Data Collection

After receiving research approval through the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST) and permission to contact schools from the Permanent Secretary of the Uganda Ministry of Education and Sports (MoES), we selected two districts for data collection due to their significant regional and linguistic contrasts. Wakiso District is in central Uganda adjacent to the capital city of Kampala and is densely populated. The dominant languages spoken in Wakiso are Luganda and English. Gulu District, by contrast is in Northern Uganda, 332 kilometers from the capital. While Gulu is home to a growing urban center, Gulu City, it is more rural than Wakiso with comparatively lower socio-economic status (SES) rates due to decades of war between the Lord’s Resistance Army and the Government of Uganda that has now ended. The predominant language spoken in Gulu is Leb Acholi, a variant of Luo. Acholi has a short average word length, 3.8 letters. Luganda, on the other hand, has a long average word length, 6.4 letters (Trudell et al., 2012).

We then selected three schools within which to conduct teacher interviews and class observations using the following criteria: First, we focused on schools where teachers indicated some familiarity with the new early grade reading curriculum, I Can Read and Write, our primary phenomenon of interest. Second, we purposefully selected at least one school from each district (Gulu and Wakiso) to enable linguistic and regional comparison. And third, the school’s Head Teacher and School Management Committee had to be willing to host researchers for an ethnographic research study.

This sampling strategy led to the selection of three primary schools: two in Gulu District (Garden Primary and Forest Primary) and one in Wakiso (Hillside Primary). The selection of these three schools also gave us the opportunity to center another axis of comparison we had not initially envisioned, between schools located in urbanized settings and those in a rural setting. Hillside Primary and Garden Primary are located in highly urban settings, while Forest Primary is situated in a rural part of Gulu District.[4] As is demonstrated in the Findings section, urbanicity emerged as a significant factor shaping teachers’ enactment of early grade reading programs, particularly around assessment.

With permission from each school’s Head Teacher, the first author and a second research team member fluent in Acholi or Luganda interviewed all Primary P1-P3 teachers in the three schools (n=12). Fieldwork was conducted at these three schools between October 2022 and March 2023. Incidentally, all participating teachers were female. While in Uganda the majority of teachers in kindergarten and the lower primary levels are usually female (cf. Ssentanda, 2014a), we recognize this lack of male teacher voices as a limit in our study that may influence findings. Teacher interviews lasted between 30-90 minutes and were guided by a semi-structured protocol that focused on teachers’ perceptions about reading pedagogies and the factors the influenced their thinking and their work as educators. Interviews were conducted in English, although participants occasionally switched to Luganda or Acholi to further explain a topic. All interviews were recorded with participants’ consent, transcribed using Sonix.ai software (see Table 1), and where necessary, translated into English for analysis. We also conducted three classroom observations of each teacher interviewed, 36 in total. Classroom observations ranged from 30 minutes to 2 hours and were conducted by at least two team members to enhance trustworthiness. Researchers sat at the back of classrooms during observations and used an Observation Guide to ensure a common set of information was gathered from each lesson in six areas: (1) demographic information about teachers and learnings present, (2) learning objectives of the lesson, (3) instructional materials available in the classroom, (4) learning activities conducted, (5) teaching methods used, and (6) languages used both by teacher and students throughout the lesson.

Table 1. Details on the teacher sample

|

Details on Teacher Sample (n=12) |

||||

|

Teacher (Pseudonym) |

School (Pseudonym) |

Grade Level |

Gender |

Number of Years Teaching |

|

Judith |

Garden |

P2 |

F |

19 |

|

Clara |

Garden |

P1 |

F |

28 |

|

Irene |

Garden |

P3 |

F |

12 |

|

Edith |

Forest |

P2 |

F |

18 |

|

Apio |

Forest |

P1 |

F |

20 |

|

Rachel |

Forest |

P1 |

F |

11 |

|

Jackie |

Forest |

P3 |

F |

12 |

|

Naomi |

Hillside |

P1 |

F |

6 |

|

Beatrice |

Hillside |

P2 |

F |

20 |

|

Fatima |

Hillside |

P2 |

F |

23 |

|

Rebecca |

Hillside |

P3 |

F |

18 |

|

Carol |

Hillside |

P3 |

F |

24 |

* Note: Pseudonyms are used in place of real school and participant names to preserve participant confidentiality and anonymity.

Data Analysis

To analyze data across the three school sites, we employed a cross-case synthesis approach (Yin 2014). In this approach, cases are compared to either confirm, disconfirm or rethink the researchers’ original expectations about how a phenomenon might replicate or vary across different sites. As a first step, we developed a codebook with a primary code rooted in our first research question – teachers’ perceptions of early grade reading reforms – and sub-codes specifying whether teachers’ perceptions were positive or negative, and any challenges teachers reported experiencing with the reforms. Using MaxQDA software, the first author coded the entire interview data corpus using these codes. Both authors then engaged in discussions to form consensus around dominant categories of teacher perceptions about the early grade reading reforms. This collaborative effort resulted in three key themes emerging: Teachers perceived the reforms as (1) representing a significant change (2) striving towards positive goals (3) and misaligned to their teaching context.

We then created Index Codes for each sample school (Saldaña, 2013), and for the two sampled regions, to answer our second research question comparing how teachers’ perceptions of the reading reforms varied across the three school sites and in different regional and linguistic settings. Doing so indicated that teachers’ perceptions of the new reading curriculum as both significant and striving toward a positive goal were commonly expressed across the three sites (Finding 1). However, perceptions of misalignment varied across three sites in two critical ways. One apparent contrast emerged between the two case schools located in Gulu District (Garden Primary and Forest Primary) and the one located in Wakiso (Hillside Primary). In Garden Primary and Forest Primary, teachers perceived the new reading reforms as bringing about extensive changes in the Acholi written orthography that presented new challenges to their instruction, while teachers in Hillside Primary did not perceive new reading curricula as impacting fundamental issues of language orthography (Finding 2). This influence of linguistic context on teachers’ perception of the new curriculum was expected and consistent with the study’s theoretical framework and research design. A second perceived misalignment was not originally anticipated and represented a point of contrast between the two school sites located in urban settings, Hillside Primary and Garden Primary, and the one located in a rural setting, Forest Primary. At Hillside and Garden Primary, teachers perceived a key misalignment between the assessment approaches used by new reading curricula and the need to prepare students for commercial high-stakes examinations offered primarily in English. However, at Forest Primary, the school located in a rural setting, teachers did not raise concerns over the curriculum’s impact on student’s preparation for high stakes exams (Finding 3).

To further understand why teachers might perceive these misalignments, we analyzed our observations of reading instruction to find moments in which teachers wrestled with language standardization and assessment issues as part of their enacted pedagogy. While this study is centered on teacher perceptions, incorporating observational data of instruction into the analysis helped us triangulate the issues teachers discussed during interviews with concrete examples of practice, increasing the validity and reliability of our findings about teacher perceptions (Lincoln & Guba, 1986).

Findings

Finding 1: Teachers perceived the emphasis on phonics to be a major change in the way they teach reading, and they generally viewed this shift to have a positive influence on student learning.

Teachers across the three schools saw new phonics-based reading pedagogies embodied in the I Can Read and Write curricular materials as a clear break from how they had taught reading before. The four veteran teachers at Hillside Primary in Wakiso District, who had all been teachers for more than eighteen years, emphasized how their reading pedagogy shifted after the arrival of the I Can Read and Write/Nsobola okusoma n’okuwandiika textbooks and teacher guides. The main shift they described was from reliance on a “whole-word” method to a phonics-based approach. For example, Fatima, a P2 teacher at Hillside Primary with 23 years of experience, described: “Many things changed. In ‘I Can Read’ many things changed. The way we used to teach is not the way we teach now.” She described that, before, she would begin by teaching students to recognize words and their meaning, and then help students write sentences with correct grammar and punctuation. But now she focuses first on letter names and sounds and then on blending words. She said, “They want these children to repeatedly get the sounds…after that, to make sure they can make those words they have blended to make sentences.” Beatrice, another P2 teacher at Hillside Primary with 20 years of experience, also emphasized the shift to a focus on teaching children phonemic awareness and phonics skills: “SHRP basically deals with the reading of sounds and training of teachers.” Rebecca, a P3 teacher at Hillside Primary with 18 years of teaching experience, agreed: “When SHRP came, some of us, we didn't know very well the sounds, but SHRP helped us so much to learn those sounds.” A fifth teacher interviewed at Hillside Primary, Naomi, a P1 teacher with only six years of experience, was not yet a teacher when the new I Can Read and Write/Nsobola okusoma n’okuwandiika curriculum was first introduced at Hillside. But she described how the emphasis on phonics in the reading curriculum differs from the way she had been trained to teach reading at her Primary Teacher College (PTC). She stated: “When I started from the college, there’s a lot we didn’t learn… I can’t tell you that we were taught those sounds, no. But as we teach…we learn them.”

Teachers at both Garden Primary and Forest Primary in Gulu also emphasized how early grade reading programs changed the model they used to teach reading. Clara, a P1 teacher at Garden Primary in Gulu with 28 years teaching experience, the most years of experience in the sample, described the switch from whole word to phonics-based instruction from her perspective:

We begin with the nukta [the alphabet]. We make them to know that first. Then afterwards we make them know the words. But the words we cannot bring in as a whole. Okay? This time we are not bringing the word as a whole for the child to know. We first break it into syllables. We know the syllables. Then after knowing the syllables, they need to know how to blend those syllables to create words.

For many teachers, like Jackie, a P3 teacher at Forest Primary in Gulu, adopting a phonics-based approach was both a significant and difficult change to make. She recounted, “It was not easy…at the beginning it was confusing. But now we are getting used to it, even the children. We keep on telling them every day so that they get the differences. And saying the sound.”

Teachers in all three schools also expressed the view that incorporating phonics into their instruction improved students’ ability to read with fluency. When asked what she thought of the phonics-based methods, Beatrice, P2 teacher at Hillside Primary, said: “These learners must have sounds very well. They can read each and every word without any difficulty. So, reading using the sound? It is good.” Naomi, a P1 teacher at Hillside Primary agreed: “It helps a lot. It helps a lot because now through those sounds, it helps the child to read.” For Clara, a P1 teacher at Garden Primary, focusing on phonics instruction “makes it easier to learn to read the words…rather than bringing whole words and making them remember.” Rebecca, a P3 teacher at Hillside Primary also agreed: “At first you could teach them the letters, but the reading was a problem. But when you are using the sound, after teaching them the sound you tell them that you read the sound, you don't read the letters, you read the sounds. At least even if you write a hard word, even if they don't know the meaning, at least they can read.” Rebecca’s comments here reflect the recognition that reading with fluency is different than reading with comprehension, or deriving meaning from text, and that reading with comprehension still often posed a challenge for her learners.

Finding 2: At Garden Primary and Forest Primary in Gulu District, where Acholi is predominant, teachers perceived the combination of the new Acholi orthography used exclusively in I Can Read and Write/An Atwëro Kwan kï Cöc and an insufficient supply of books to cover large class sizes as exacerbating gaps between school and community literacies.

While teachers valued the phonics-based methods and materials that accompanied them, they also identified misalignments between the highly structured I Can Read and Write pedagogical approach and particular contexts of their teaching environment. One key issue emerged in the two sample schools based in Gulu District: Garden Primary and Forest Primary. At these two schools, the arrival of the new Acholi-version of the I Can Read and Write curriculum, An Atwëro Kwan kï Cöc, also marked the arrival of a new orthography, or writing system, for the Acholi language that had not previously been used in schools or the broader community, as elaborated on in the Context section.

The introduction of the new orthography represented a significant shift for teachers at Garden Primary and Forest Primary. While these teachers demonstrated a nuanced understanding of the purpose behind the changes in the new writing system and generally agreed that the addition of vowels and tonal markings could make it easier for early readers to differentiate between words with the same spelling but different pronunciations and meanings, they also felt stress at being asked to learn a new method of writing and alter language habits built over a lifetime. As a result, their use of the new writing system during class instruction was mixed.

One day, in her P3 class at Garden Primary, for example, Irene taught a lesson using An Atwëro Kwan kï Cöc that focused on a story about a woman who worked hard in her garden. In her writing on the chalkboard during the lesson, Irene did not include tonal markings for multiple words that included them in the An Atwëro Kwan kï Cöc book that had been passed out to the students. Later, in an interview, Irene discussed the challenge of remembering to use the new writing system that was different than the one she’d used for so many years. She said “It’s challenging if that’s not the way you were taught. Now you as the teacher have to learn something new.” She said that she feels frustrated when she forgets to use the new letters, and her students often point it out to her. “They can remind you that, ‘Madam you did not put the dots,’” she said. For Irene, one of the most senior teachers at Garden Primary who was highly regarded by her peers and head teacher, the orthography shift also represented a reconfiguration of her authority and sense of expertise as an educator. This challenge was compounded by the fact that Acholi was not Irene’s first language. She grew up speaking Lango, another Luo variant with significant lexical similarity to Acholi but differences in pronunciation as well as some vocabulary. “So now a teacher might say ‘well if I’m not an Acholi, I cannot teach with that [textbook].’…When you are not well versed it becomes a problem,” she explained. Irene’s experience echoes Wenske and Ssentanda (2021), who found similar frustration amongst Ateso speaking teachers who were asked to adopt a new Ateso orthography as part of early grade reading reforms: “One of the reasons the SHRP program is met with reluctance among teachers,” they write, “is that they have been required to learn a new way of writing” (p. 10).

Another reason teachers at Garden Primary and Forest Primary gave for not using the writing system consistently was the fact that An Atwëro Kwan kï Cöc was the only book or educational material that used it. This meant that children were exposed to different writing systems as they moved from one grade level to another within their school. Irene described this challenge in an interview: “So in P1 they have learned this one, and they also find it in P2. But if they don’t also find it in P3, they will get confused.” This gap also extends outside of school into the community where the new orthography is not in use, such as in religious services, medical offices, and the market. Clara, the P1 teacher at Garden Primary, reflected on the consequences for children who navigate multiple writing systems as they begin to learn to read: “It is difficult for children to understand if they are reading another text in Luo. So, when the child just goes to the library and takes a Luo textbook you will not get those new things that you are telling them about in school...That’s when they come to school with the wrong pronunciation for a particular word.” This statement indicates how early grade reading reforms may increase the gap between school and community-based literacy and present dilemmas for students as they develop nascent reading and writing skills. Edith, a P2 teacher at Forest Primary, also pointed out that different Acholi-speaking regions use different pronunciations, further complicating the adjustment to a new alphabet with new tonal markings. “Though they may all be Acholi, this side we may have different pronunciation,” Edith explained. “So, you find that from here we may be putting the dots, and yet from there they don’t put the dots...So, you find that people do understand differently. And that’s why putting that dot sometimes disturbs us,” she said.

The challenge of switching to a new Acholi writing system was made more difficult by the fact that An Atwëro Kwan kï Cöc books at Forest Primary and Garden Primary were in limited supply and deteriorating condition. Teachers at both Garden Primary and Forest Primary also expressed a lack of confidence that An Atwëro Kwan kï Cöc books would be replaced, limiting their commitment to shifting to the new writing system and reading pedagogies. At Garden Primary, Clara, the P1 teacher, described how her fluctuating class size led to book shortages. “When they did the training, they gave us the book according to the number of children we have in the class. By that time, we were having only forty children in the class,” she recalled. But in the eight years since the books arrived, her class size has more than doubled to over 90 students in Term 1 of 2023. Clara recognized how the lack of books influenced her implementation of the curriculum. She said:

In this book here, you are not supposed to share that. Now, you have seen them sharing. One book, two children…Now, when it comes to finger pointing [tracing the words as they read aloud], they have to use their finger to follow the words they are reading. But if they're sharing, somebody is also pointing that way. Even if you tell them, ‘First wait and let the first person read then you will exchange,’ you can see somebody pulling to be the first to begin finger pointing.

Irene, the P3 class teacher at Garden Primary, had 78 copies of An Atwëro Kwan kï Cöc for her class of 110 students, and the copies she did have were in poor condition after many years of use. Irene used her status as a senior teacher to ask her head teacher for funds to print copies of the book, despite the fact that the books are not supposed to be reproduced without permission. Irene described how she “cried to her head teacher” for help to make copies. She said she told her head teacher that she would refuse to teach with An Atwëro Kwan kï Cöc if she wasn’t able to provide each student a book. Her head teacher ended up giving her funds to make 30 copies, which she made herself at a local copy shop. Irene recognized her situation was unique. Her stature as a teacher leader in her school, and her school’s proximity to town, made it possible for her to take matters into her own hands. According to her, however, “Some teachers are saying ‘for us we have left it.’ Because the books are not even there.”

Teachers at Forest Primary also experienced book shortages and deterioration. For example, in one lesson taught by Edith, the P2 teacher at Forest Primary, a pupil raised his hand during the lesson to tell Edith that his book did not have the page she was referring to in the lesson. It had been ripped out. After the lesson, Edith reflected: “The book has now taken long…They have not yet replaced or added since it was brought.” Teachers at Forest Primary did not have photocopies of the book to use, as the teachers at Garden Primary did, and they felt uncertain the books would be replenished. Moreover, Apio, the P1 teacher at Forest Primary, explained that the books “are now torn…I don't know if there is a plan for replacing.” When asked what she would do if An Atwëro Kwan kï Cöc books weren’t replenished soon, she replied: “The teacher should be creative. We use the ones which we already have.”

Finding 3: At Hillside Primary and Garden Primary, the two schools in urban settings, teachers perceived a key misalignment between the assessment approaches used by new reading curricula and the need to prepare students for commercial and high-stakes examinations offered primarily in English.

A second misalignment between the design of the I Can Read and Write curriculum model and teachers’ social and political environments emerged from the two sample schools based in highly urban contexts, Hillside Primary and Garden Primary. At these schools, teachers emphasized that the assessment approach utilized in I Can Read and Write put them at a disadvantage compared to private schools concentrated in urban areas that use examinations developed by commercial companies. These exams are perceived by parents and many teachers to afford high social standing to students who perform well and to indicate whether students are on-track to succeed on their Primary Leaving Examinations (PLEs), a key determinant of access to secondary school (Ssentanda et al., 2016).

The I Can Read and Write curriculum does include an assessment model, but it is designed very differently than these commercial examinations. First, rather than offer preset exam questions that teachers can administer to students, the curriculum provides a continuous assessment and monitoring form (CAM) with identified competencies. Teachers are expected to develop questions aligned to these competencies, assess a few students each day, and track student progress on the CAM form throughout the term. The I Can Read and Write teacher’s guide does provide some example exam questions that teachers can use to develop their own exams for students at the end of a term. These summative exam questions require students to use the I Can Read and Write textbook and instructs teachers to note whether students are exceeding, meeting or not meeting expectations, but not to give an overall score.

Teachers at Hillside Primary and Garden Primary felt that this assessment approach in I Can Read and Write was insufficient to the expectations they faced from parents, students and their supervisors, and they often took it upon themselves to offer the commercial examinations to their learners. Rebecca, the P3 teacher at Hillside Primary, explained: “According to these private schools, the competition for them, they could give the test…At first, they told us that we have to assess only with I Can Read and Write. But for us now, we are doing both. We assess and again, we give the exams. Yes, because of the pressure from the private schools.”

Teachers’ decision to incorporate commercial exams into their reading instruction also led them to include lesson content aligned to these exams, beyond what was provided in I Can Read and Write. Naomi, a P1 teacher at Hillside Primary, explained how the misalignment between I Can Read and Write and the examinations created a gap for teachers to fill: “There are many, many things that are not in that book [I Can Read and Write]. But you find them in exams. So, the way exams are set, this book is not on that line. You can’t use that book to answer these questions that are set.” However, the highly structured nature of the I Can Read and Write curriculum made it difficult for teachers like Naomi to integrate other curricular material into their literacy instruction. Naomi further explained:

That book, for those who are using it, it is limiting us. We can't integrate it with other resources, with other tests. It's not very easy because it gives you work for day one, day two, day three, up to Friday. It gives you what to teach on those specific days, and you find that when you follow it only there are very many things that the child is not going to learn.

A particular concern expressed by Fatima, a P2 teacher at Hillside Primary, was the lack of science and SST (Social Studies) content included in I Can Read and Write. She said, referring to the I Can Read and Write curriculum produced by the SHRP and LARA programs, “This literacy of SHRP and LARA, it is all about reading. It has no science. It has no SST (social studies).” Fatima’s concern about a lack of science and SST content is partly an issue with the Thematic Curriculum that predated the I Can Read and Write curriculum. Enacted in 2006, the Thematic Curriculum specifies learning outcomes for early primary grades organized into 12 broad themes. A recommended daily timetable details how teachers should address the themes across different subject areas, including: literacy, mathematics, physical education, religious education, arts, music, news, storytime or unstructured free periods. According to the P1 version of the Thematic Curriculum, “The content, concepts and skills such as Science and SST (Social Studies) have been rearranged into themes that are familiar to the learners’ experiences,” (NCDC, 2016, p. 5).

But the introduction of I Can Read and Write, a highly structured curriculum, created a new level of constraint over what content Fatima could incorporate into her literacy instruction. She explained: “We are supposed to use that book throughout. As the government policy. But we find that if we want to be among the best we have to intermarry.” By ‘intermarry’, Fatima meant incorporating additional content not included in I Can Read and Write into her teaching. Therefore, Fatima still took it upon herself to supplement I Can Read and Write with science and SST content, even though it added to her already extensive workload: “We double it. We handle this part, and we handle the other part. It is too tiresome,” she said.

The pressure to use external exams not tied to the I Can Read and Write curriculum was also experienced at Garden Primary in Gulu District. During fieldwork, the school spent two days administering commercial exams to students. The exams took place early in the term and were designed to give teachers and parents a picture of students’ baseline learning levels. During an interview, Irene, the P3 teacher at Garden Primary, described how the school balances the use of externally purchased preset exams with the exams they develop themselves based on their own curriculum:

We buy beginning of term and then midterm we buy from the people who normally make and then they sell. But third term is made by the teachers... So they pick teachers for P1, P2 and P3. They sit together and they write the exam.

Irene recognized the misalignment between these exams and the I Can Read and Write curriculum. She said, “We have raised this issue, that is why it they are not setting [An Atwëro Kwan kï Cöc]?”, referring to the aforementioned beginning of term and midterm exams. She said that there are some companies who are starting to develop new exams aligned with An Atwëro Kwan kï Cöc in response to this challenge, but they are not yet widely available or widely used.

Discussion

Uganda is just one of more than fifty countries where large-scale donor-funded programs have been implemented to boost outcomes in early reading achievement (Graham & Kelly, 2018; Piper & Dubeck, 2024). While these initiatives in Uganda have varied in some structural aspects (e.g. SHRP and LARA were implemented through partnerships between government and non-governmental actors, while UTSEP is primarily government-run) they have all relied on a common core curriculum, I Can Read and Write, that utilizes a phonics-based and highly structured reading pedagogy. In this research we sought to answer two questions about this new early grade reading curriculum:

1. How do Ugandan early primary teachers perceive and experience changes to the early grade reading curricula brought about by recent donor-funded programs?

2. How do teachers’ perceptions and experiences vary across two linguistic and regional settings in northern and central Uganda, respectively?

In reference to our first question, we found that teachers in all three schools interpreted I Can Read and Write as marking a fundamental shift in the way reading is taught in Uganda. Teachers who entered teaching before 2012 described changing their reading instruction from a method focused on helping students recognize whole words to a phonics-based approach that prioritizes map the sounds of a language onto letters and groups of letters (phonics). Teachers also saw this focus on phonics as improving their students’ ability to read with fluency, although they still cited comprehension as a challenge. This replicates similar studies that found positive teacher views of the new reading curriculum (Wenske & Ssentanda, 2021) and positive impacts of the curriculum on student reading outcomes (Brunette et al., 2019; Uwezo Uganda, 2019).

When answering our second research question, we observed how reforms created new expectations sometimes misaligned with various cultural, economic, and political expectations placed upon teachers in Uganda across different linguistic and regional contexts. First, the reforms positioned teachers in the two schools where Acholi is dominant, Garden Primary and Forest Primary, as the arbiters of a shift to a new system of writing Acholi not previously in use. The arrival of a new Acholi orthography reconfigured teachers’ authority. They became novices rather than experts in a new writing system at odds with what children encountered at religious services, in the market, and other spaces where they encounter written Acholi. Comparing these teachers’ experiences of orthography reform to teachers in Luganda dominant schools where such orthography changes were not evident demonstrates how the introduction of a standardized curriculum across diverse contexts does not ask all teachers to make the same magnitude of change to their practice. This suggests that in cases where curricular reform instigates significant orthography changes, additional time and resources should be provided to help teachers adapt to these shifts (Trudell, 2007; Trudell & Schroeder, 2007). It is also critical to ensure that new textbooks and curricular materials are in sufficient supply, since they may be the only ones that utilize the new writing system. More broadly, given that “orthographies are consequential social artifacts” and are “bound up in people’s social experiences” (Limerick, 2017, p. 107), efforts to improve early literacy instruction that raise questions about orthography necessitate deep and long-term engagement with community stakeholders beyond schools with ties to a language’s history and influence over its future use.

Second, the reforms situated teachers in the two schools in highly urban settings, Garden Primary and Hillside Primary, in the middle of competing viewpoints regarding the purpose of student assessment and of schooling itself. The designers of the new I Can Read and Write curriculum believed that student learning is best advanced by using frequent low-stakes assessments of learning conducted in a child’s first language, or mother-tongue. This led to the adoption of a continuous assessment model (CAM) that asks teachers already burdened by large classes to assess students daily and keep detailed records in a CAM form provided in their teaching guidebook. But, at Hillside Primary and Garden Primary, teachers felt pressure from parents and administrators to provide additional information about student progress conferred by commercial examinations, primarily administered in English, and used in private schools that yield high status. This impact of the examination context on teachers’ views of curriculum reforms has also been identified by researchers during previous reform initiatives and thus is an ongoing challenge (e.g. Altinyelken et al., 2014; Ssentanda, 2014b; Tembe & Norton, 2008;). Consequently, teachers at Garden Primary and Hillside Primary integrated these commercial exams into the I Can Read and Write curriculum that was not designed with them in mind.

Conclusion

These findings show the limits of interventions, currently ascendent in international development and policy circles, that seek to improve educational quality primarily through the introduction of highly structured pedagogies and curricular materials (Piper & Dubeck, 2024). Teachers in this study showed a strong understanding of the purpose behind the new I Can Read and Write curriculum as well as the specific reading pedagogies the new curriculum asked them to adopt. While they valued the new pedagogies and curricular materials, their ability and willingness to adopt them was shaped by contextual factors, including the insufficient supply and unreliable replenishment of materials provided, the magnitude of language orthography change they were asked to undertake, and the ongoing pressures they face to prepare students for certain examinations. To sustain improvements in literacy instruction and learning outcomes, policymakers and program funders need to engage these factors that manifest outside the classroom but nonetheless shape teachers’ perceptions and enactments of reform efforts.

This paper also points to the methodological contribution of comparative qualitative studies that shed light on the ways education reforms often play out differently, and in unexpected ways, as they travel across diverse contexts (Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017). Like prisms that refract light into different colors, education policies take on different forms across sites that may deviate from intended designs. Comparative research reveals opportunities for policymakers to design more tailored interventions that can be sustained over time. For example, in cases where curricular reforms raise questions about orthographies, such as at Garden Primary and Forest Primary, extra effort should be made to afford time for community stakeholders to consider such changes and for teachers to participate in continuous in-service training. In these cases, it is also paramount that books be adequately supplied, since they may be the only materials available using the new orthography.

Future research can address several limitations in this study and pursue additional lines of comparative analysis. Our data collection was limited to a six-month period; future studies could adopt stronger longitudinal ethnographic methods to enable a deeper analysis of the interaction between teachers’ cultural and political environments and enacted classroom instruction. Second, different axes of comparison could shed further light on teacher experiences that are common and/or particular to context. For example, this study lacks data on a school in a rural context that is primarily Luganda speaking, limiting its ability to consider teacher experiences with early grade reading reform common across rural settings in different linguistic contexts. Third, future studies could incorporate a more diverse teacher sample. This study was limited in its inclusion of only female primary school teachers.

Finally, future studies can account for the impacts of the recent shuttering of USAID by the Trump Administration, and its effects on ongoing early grade reading interventions in Uganda, such as the USAID-funded Integrated Youth and Community Development (ICYD) Activity. ICYD’s mandate focused on reforming pre-service teacher training to align with the I Can Read and Write literacy model, as well as providing new materials and pre-service teacher training opportunities. It will be important to document whether and how sudden changes in USAID programming impact teachers, and how teachers make sense of such fluctuations as they adapt their instruction, once again, to a new set of realities.

References

Altinyelken, H. K. (2010). Curriculum change in Uganda: Teacher perspectives on the new thematic curriculum. International Journal of Educational Development, 30(2), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2009.03.004

Altinyelken, H. K., Moorcroft, S., & van der Draai, H. (2014). The dilemmas and complexities of implementing language-in-education policies: perspectives from urban and rural contexts in Uganda. International Journal of Educational Development, 36, 90-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2013.11.001

Atkinson, R. (1994). The Roots of Ethnicity: The Origins of the Acholi of Uganda before 1800. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Ball, S. J., Maguire, M., & Braun, A. (2012). How Schools Do Policy. Routledge.

Bartlett, L., & Vavrus, F. (2017). Rethinking Case Study Research. Routledge.

Brunette, T., Piper, B., Jordan, R., King, S., & Nabacwa, R. (2019). The Impact of Mother Tongue Reading Instruction in Twelve Ugandan Languages. Comparative Education Review, 63(4), 591-612.

Ertmer, P. & Newby, T. J. (2013). Behaviorism, Cognitivism, Constructivism: Comparing Critical Features from an Instructional Design Perspective. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 26(2), 43-71. https://doi.org/10.1002/piq.21143

Evans, D. K., & Mendez Acosta, A. (2020). Education in Africa: What are We Learning? Working Paper No. 542. Center for Global Development.

Graham, J., & Kelly, S. (2018). How effective are early grade reading interventions? A review of evidence. Educational Research Review, 27, 155-175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.03.006

Johnson, S. M., Berg, J. H., & Donaldson, M. L. (2005). Who stays in teaching and why: a review of the literature on teacher retention. The Project on the Next Generation of Teachers, Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Johnson, D. C. (2009). Ethnography of language policy. Language Policy, 8(2), 139–159. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10993-009-9136-9

Limerick, N. (2017). Kichwa or Quichua? Competing Alphabets, Political Histories and Complicated Reading in Indigenous Languages. Comparative Education Review, 62(1). https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/695487

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1986). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. Naturalistic evaluation, 1986(30), 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.1427

McCarty, T. L. & Warhol, L. (2011). The anthropology of language planning and policy. In B. Levinson & M. Pollock (Eds.), A Companion to the Anthropology of Education (pp. 177-196). Wiley-Blackwell.

Menken, K., & García, O. (2010). Negotiating language policies in schools: Educators as Policymakers. Routledge.

NCDC. (2016). Primary school curriculum primary 1. National Curriculum Development Centre.

Piper, B., & Dubeck, M. (2024). Responding to the learning crisis: Structured pedagogy in sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Educational Development, 109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2024.103095

Otim, P. W. (2024). Acholi Intellectuals: Knowledge, power and the making of colonial northern Uganda, 1850-1960. Ohio University Press.

Saldaña, J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage.

Simons, G. F., & Fennig, C. D. (2019). Ethnologue: Languages of the World (20th ed.). Ethnologue.

Spillane, J. P., Hopkins, M., & Sweet, T. (2015). Intra- and interschool instructional networks: Information flow and knowledge production in education systems. American Journal of Education, 122(1). https://doi.org/10.1086/683292

Ssentanda, M. E. (2014a). Mother tongue education and transition to English medium education in Uganda: Teachers’ perspectives and practices versus language policy and curriculum [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Stellenbosch.

Ssentanda, M. (2014b). The Challenges of teaching reading in Uganda: Curriculum guidelines and language policy viewed from the classroom. Apples – Journal of Applied Language Studies, 8(2), 1–22.

Ssentanda, M., Huddlestone, K., & Southwood, F. (2016). The politics of mother tongue education: The case of Uganda. Per Linguam, 32(3), 60–78. https://doi.org/10.5785/32-3-689

Ssentanda, M., & Wenske, R. (2023). Either/or literacies: teachers’ views on the implementation of the Thematic Curriculum in Uganda. Compare, 53(6), 1098-1116. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2021.1995700

Stern, J., & Piper, B. (2019). Resetting Targets: Why Large Effect Sizes in Education Development Programs Are Not Resulting in More Students Reading at Benchmark. RTI Press.

Tembe, J., & Norton, B. (2008). Promoting Local Languages in Ugandan Primary Schools: The Community as Stakeholder. Canadian Modern Language Review, 65(1). https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.65.1.33

Trudell, B. (2007). Local community perspectives and language of education in sub-Saharan African communities. International Journal of Educational Development, 27(5), 552-563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2007.02.002

Trudell, B., & Schroeder, L. (2007). Reading Methodologies for African Languages: Avoiding linguistic and pedagogical imperialism. Language Culture and Curriculum, 20(3), 165-180. https://doi.org/10.2167/lcc333.0

Trudell, B., Ngozi, R., Nannyombi, P., Dokotum, O., van Ginkel, A., & Trudell, J. (2012). Local Language-Medium Instruction in Ugandan Languages: An Assessment of Language Readiness. Unpublished paper. Prepared for USAID under the Uganda School Health and Reading Program, cooperative agreement no. AID-617- 12-00002. SIL LEAD International.

Uwezo Uganda. (2019). Are Our Children Learning? Uwezo Uganda Eighth Learning Assessment Report. Twaweza East Africa.

Vavrus, F. (2009). The cultural politics of constructivist pedagogies: Teacher education reform in the United Republic of Tanzania. International Journal of Educational Development, 29(3), 303-311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2008.05.002

Wagner, D. (2018). Learning as Development: Rethinking International Education in a Changing World. Routledge.

Wenske, R., & Ssentanda, M. (2021). "I think it was a trick to fail Eastern": A multi-level analysis of teachers' views on the implementation of the SHRP Program in Uganda. International Journal of Educational Development, 80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2020.102309

World Bank. (2018). World Development Report. https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2018

Yin, R. K. (2014). Case Study Research: Design and Methods (5th Ed.). Sage.