Vol 9, No 1 (2025)

https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.6232

Forum

Demodernizing Schooling: Educating for future worlds without colonial empires’ resources

Jeremy Jiménez

The State University of New York at Cortland

Email: jeremy.jimenez@cortland.edu

Keywords: decoloniality, education for sustainability, modernity, demodernization, relocalization

The authors of “Beyond Exceptionalism” (Conolly et al., 2025 - in this issue) challenge the assumption of Scandinavian countries’ ’exceptional’ commitment to educational egalitarianism with ample evidence about the need to decolonize their respective national curricula, stating:

coloniality in education promotes European modernity, justifies de facto white supremacy, and positions the knowledges and ways of life of others as inferior or irrelevant. But how do we dismantle such an entrenched system? (Conolly et al., 2025, p. 5).

My own experience within a Nordic educational system was during my time as a Fulbright Roving scholar[1] (2009-2010), where I traveled to several dozen school districts across Norway to give presentations about the history, culture and policies of the United States. At first glance, a U.S. resident can easily be enamored of Norway’s equitable, centralized funding for its schools; regardless of a town’s or city’s population, region or wealth. I was consistently impressed with the various schools’ facilities as well as the resources that their classroom teachers had at their disposal in all of the many schools that I visited. Although I admittedly didn’t spend long enough at any particular school to perceive any social dynamics that weren’t readily apparent, the prevailing sentiment I experienced from nearly all of the teachers and students in schools from Stavanger in the South to Vardø in the North was positive enthusiasm and a professed willingness to consider new perspectives.

Nevertheless, at times I would see evidence of students’ discriminatory attitudes towards the “other”, such as on some occasions where students came up to me after my immigration presentation to show me inflammatory YouTube videos warning that, due to European countries’ supposedly lax immigration policies and higher birth rates among Muslim immigrants, most of Europe will be Muslim within twenty years. Occasionally teachers would also have to intervene when their students would make racist comments about US President Barack Obama. What I aim to address in this Forum essay, however, is not to focus on how my experiences might validate nor challenge these authors’ thesis but rather to respond to the key question they posed, namely, when they inquired if education is a “problem or solution” towards creating “a decolonial, socially equitable, and sustainable future” (Conolly et al., 2025, p. 10). The authors recognize that they “are both products of, and actors within, the hegemonic educational systems that we seek to critique” (p. 4), thus acknowledging their own complicity (of which I share). They also effectively argue how a deep-rooted Nordic ideology conflating egalitarianism with ’sameness’ pervades across Nordic school settings and discuss some ways to incorporate Indigenous perspectives into these educational settings to help decolonize them. However, one neglected albeit crucial component to add to the authors’ goal of dismantl(ing) such an “entrenched system” (p. 5) is to interrogate whether such institutions of ‘European modernity’ can ever actually be sustainable, which I would describe as when the lifestyle choices of one generation do not inhibit the capacity of future generations to enjoy a similar standard of living, and when other species’ long-term livelihoods are not negatively impacted by such lifestyles.

During my time in Norway, I viewed the many creatively designed schools equipped with the latest technological affordances with awe and admiration as exemplars of how state revenue can be beneficially utilized to improve societal well-being. However, I am now acutely aware of the unseen harms wrought by continually building such new facilities and acquiring the latest digital learning tools, namely, the trail of ecocide that these products of global trade leave in their wake, whether through mining, deforestation, or simply the fossil fuels necessary for nearly all their material extraction, manufacturing and global transport (Jensen et al., 2021; Jiménez, 2021). The capacity to provide such infrastructure and gadgetry comes from a high tax rate coupled with the largesse of Norway’s oil reserves; exported alongside this oil, however, is also an increasingly dire rate of planetary warming (Hansen et al., 2025).

Further, global warming is only one among nine ways in which continued industrialization harms our life support systems (Liboroin, 2021; Steffen, Richardson et al., 2015). Yet, it is only threatened ’planetary boundary’ that gets nearly all of the attention, given that its supposed solutions enable us to carry on our industrial assault on planetary life under the greenwashing illusion that substituting coal mines for solar panels and hydroelectric dams is a viable path to a more sustainable future (Jiménez & Kabachnik, 2023). Many other scholars have demonstrated that so-called ’renewable’ forms of energy are just a newer manifestation of ecocidal colonial cultures (Jensen et al., 2021; Seibert & Rees, 2021), that is, trying to solve the problems of modernity with more modernity.

As such, dismantling ’modernity’ cannot be limited to recognizing harm in thoughts, words, and social organization; it requires that we also acknowledge our own complicity in the comforts of industrial modernity. A decolonial education that doesn’t address environmental devastation brought by modernity may achieve some beneficial outcomes such as changing hearts and minds and making schools more inclusive at the local level, but it comes at the expense of continued colonial exploitations beyond Scandinavia’s borders (Liboroin, 2022; Machado de Oliveira, 2021). Thus, schooling systems with decolonized curriculums and pedagogies that still rely on an unrelenting supply of digital devices and contemporary infrastructure upgrades (using unsustainable material inputs) can never be sustainable, because the required resources are limited in supply and their extraction is environmentally deleterious (Jiménez, 2022; Yunkaporta, 2020).

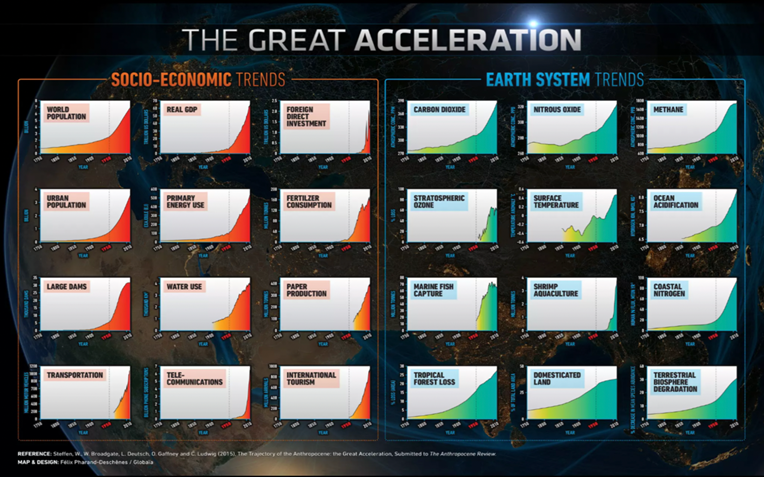

Even the authors themselves note that “despite legislation strengthening reindeer-herder rights, the exploitation of natural resources within Sápmi has significantly increased since the mid-1990s” (Conelly et al., 2025, p. 8). This is the essence of the colonial project – trying to solve the problems of modernity (states’ wanton facilitation of environmental devastation through global trade, economic growth, and its concomitant habitat destruction) with more modernity (states putting in laws in place to mitigate this environmental devastation). The history of the past few centuries (see Chart 1) has made clear that modern industrial societies’ environmental protection legislation has not, nor will it ever, reverse or even prevent our ever-worsening environmental degradation; when some improvements in environmental conditions are observed in settler colonial states, this usually occurs because they are outsourcing their manufactured pollution elsewhere (Liboroin, 2022; Machado de Oliveira, 2021). In short, there is no way to protect Earths’ remaining communities of life without abandoning our investment in an industrial system detrimental to all life.

Chart 1. The relationship between modernity’s economic expansion and its corollary environmental costs

Source: “The trajectory of the Anthropocene” (Steffen, Broadgate et al., 2015)

As one of their recommended responses, the authors discuss researchers who use the Indigenous scholar Andreotti’s (2012) HEADSUP tool for helping students learn about the relationship between education and colonialism. Interestingly, though, her more recent work discusses the pitfalls on inviting Indigenous voices into the house of modernity, arguing that inclusion often ends up being “conditional upon assent to a horizon of hope oriented by shared goals and coherence around continued support for existing social, political, and economic norms” and is limited only to “expanding access to existing institutions” (Machado de Oliveira, 2021, p. 89), which also thus limits our Overton window on re-imagined futures. At best, she sees this project of inclusion having value for only a limited time, stating:

While equity, diversity, and inclusion within modernity can be important in the short term, neither inclusion nor representation is a viable response in the long run: modern institutions or capitalism led by Black, Indigenous, or people of color cannot be the endgame because this would still reproduce the harms necessary for sustaining modernity (Machado de Oliveira, 2021, p. 184).

While she acknowledges that “divestment (from modernity) is practically impossible” (Machado de Oliveira, 2021, p. 238), she instead argues for disinvestment. Disinvestment means accepting that because the access to state-of-the art equipment and facilities has always depended on exploiting human and other natural resources of the Global South and that we are nearing the end of nation-states’ capacity to continually provide such benefits for their citizenry, we should “hospice” our commitment to the unrealizable futures promised by such institutions and infrastructures of modern development. What might this look like in practice?

To be clear, there is no easy path forward; paying the price for our ecological overshoot will continue to bring hardships for humans and our non-human kin for many decades to come, regardless of the speed of our letting go of modernity’s trappings (Bendell, 2023; Catton, 1982). And what makes this particularly complex is not just that most of us are currently dependent on modernity to varying degrees for our livelihoods, but that modernity’s affordances have in some ways opened up possibilities for more fulfilling lives. One particularly inspirational example can be found in the recent documentary about Mats “Ibelin” Steen[2], a Norwegian with Duchennes muscular distrophy who was able to improve the lives of so many people (including himself) because of his ability to leverage the affordances of modern digital technology.[3] But disinvestment doesn’t mean immediately dismantling our dependence on modernity; this would have particularly deleterious consequences, as evidenced by the consequences of U.S. President Trump’s sudden dismantling of its global aid programs and other medical support services.

Rather, disinvestment means first recognizing our looming predicament, that is, that modern industrial life is unsustainable and will eventually become untenable. This will happen either because continued industrialization will further shrink the habitable zones for other species (along with many Indigenous communities that are stewards of these richly biodiverse ecosystems) or because the rare Earth and other necessary mineral resources to sustain modernity can no longer be affordably accessed (Yunkaporta, 2020). By thus committing to no longer creating buildings that are unsustainably constructed[4] and continually upgrading schools’ technological capacities (and perhaps restricting technology’s affordances to those people most in need, such as Ibelin), the existing and future resources of modernity can be used more scarcely and allocated towards survival needs that are general (food production) and specific (insulin production for people with Diabetes).

At the same time, people in their respective bio-regions can begin to discuss the long eventual process of re-localization (Rees, 2019) in which school administrations and faculty work together with other community members to learn how they can best prepare their students for necessarily simpler lives ahead, in which resources needed for survival are increasingly, and eventually entirely, produced locally. Everyone has much to learn from the Indigenous elders of their respective bio-regions (which the authors appropriately point out), especially about how to live more sustainably. But part and parcel alongside this level of decolonizing comes a commitment to withering away a centralized education system, as each community begins to focus on the education needed to make their own communities viable without state resources obtained through ecocide.

In recalling my own Fulbright travels, I remember quite fondly the time I had spent with Indigenous (Sami) teachers who lived in places such as Kautokeino and Alta who sometimes went even beyond the gracious hospitality of my other Norwegian teacher hosts by inviting me to stay at their homes. Receiving free Fulbright-funded hotel accommodations, I turned down these invites because I didn’t want to be an unnecessary burden. But what I didn’t appreciate then as I do now is that these home invites reflected these Indigenous teachers’ commitment to building relationships with others, which is a vitally more important component for long-term sustainable living than any of the outputs of industrial modernity; as Aboriginal scholar Tyson Yunkaporta says, “relationships are the only way to safely store data in the long-term” (Yunkaporta, 2024, p. 13). In conclusion, Conolly et al. (2025) effectively relayed the importance of recognizing and resisting the colonial mindset, both to reduce harms towards ‘the other’ as well as positively challenging settler-colonial attitudes and practices. My own intellectual contribution this decolonizing movement is advocating for is that environmental and ecological issues remain forefront to all of our advocacy; by doing so, we’ll be better positioned to sustain communities of life after the eventual collapse of the house of modernity (Machado de Oliveira, 2021; Yunkaporta, 2020).

References

Andreotti, V. (2012). Editor’s Preface: HEADS UP. Critical Literacy: Theories and Practices, 6(1), 1-3.

Bendell, J. (2023). Breaking together: A freedom-loving response to collapse. Good Works: Schumacher Institute.

Catton, W. R. (1982). Overshoot: The ecological basis of revolutionary change. University of Illinois Press.

Conolly, J., Abraham, G. Y., Bergersen, A., Bratland, K., Jæger, K., Jensen, A. A., & Lassen, I. (2025). Beyond exceptionalism: Decolonising the Nordic educational mindset. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education (NJCIE), 9(1). https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.5989

Garrett, T. J., Grasselli, M., & Keen, S. (2020). Past world economic production constrains current energy demands: Persistent scaling with implications for economic growth and climate change. PLoS ONE, 15(8), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237672

Hansen, J. E., Kharecha, P., Sato, M., Tselioudis, G., Kelly, J., Bauer, S. E., Ruedy, R., Jeong, E., Jin, Q., Rignot, E., Velicogna, I., Schoeberl, M. R., Schuckmann, K. von, Amponsem, J., Cao, J., Keskinen, A., Li, J., & Pokela, A. (2025). Global Warming Has Accelerated: Are the United Nations and the Public Well-Informed? Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 67(1), 6–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2025.2434494

Jensen, D., Lierre, K., & Wilbert, M. (2021). Bright green lies: How the environmental movement lost its way and what we can do about it. Monkfish Book Publishing.

Jiménez, J. (2021) The Hidden Cost of Zooming: Exploring Non-Digital Pedagogies for a more sustainable future. Films for the Feminist Classroom, 11(1). http://ffc.twu.edu/issue_11-1/feat_Jimenez_11-1.html

Jiménez, J. (2022, May 23). Why the UN must rely more on indigenous wisdom and less on fossil fuels. Resilience. https://www.resilience.org/resilience-author/jeremy-jimenez/

Jiménez, J., & Kabachnik, P. (2023). Indigenizing environmental sustainability curriculum and pedagogy: confronting our global ecological crisis via Indigenous sustainabilities. Teaching in Higher Education, 28(5), 1095-1107. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2023.2193666

Liboiron, M. (2021). Pollution is Colonialism. Duke University Press.

Machado de Oliveira (Andreotti), V. (2021). Hospicing modernity: Facing humanity’s wrongs and implications for social activism. North Atlantic Books.

Rees, W. (2019). Why Place-Based Food Systems? Food Security in a Chaotic World. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 9(A), 5-13. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2019.091.014

Siebert, M. K., & Rees, W. E. (2021). Through the Eye of a Needle: An Eco-Heterodox Perspective on the Renewable Energy Transition. Energies, 14. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0401356

Steffen, W., Broadgate, W., Deutsch, L., Gaffney, O., & Ludwig, C. (2015). The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration. The Anthropocene Review, 2(1), 81-98. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053019614564785

Steffen, W., Richardson, K., Rockström, J., Cornell S. E., Fetzer, I., Bennett, E. M., Biggs, R., Carpenter, S. R., de Vries, W., de Wit, C. A., Folke, C., Gerten, D., Heinke, J., Mace, G. M., Persson, L. M., Ramanathan, V., Reyers, B., & Sörlin, S. (2015). Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science, 347(6223). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1259855

Yunkaporta, T. (2020). Sand talk: How indigenous thinking can save the world. Harper One.

Yunkaporta, T. (2024). Right Story, Wrong Story: Adventure sin Indigenous Thinking. Text Publishing.