Vol 9, No 3 (2025)

https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.6326

Non-compulsory Instrumental Music Education in Poland and Norway: Perspectives on Accessibility, Curriculum Framework and Learning Goals in Two Different Music Education Systems

Katarzyna Julia Leikvoll

University of Bergen

Email: julia.leikvoll@uib.no

Abstract

This article compares non-compulsory instrumental music education systems in Norway and Poland, by describing their organisation, accessibility, educational goals, curriculum framework, and the target group, and discussing consequences the chosen form of organisation and vision might have for the users. The analysis of government documents and statistics shows that while Polish Music Centres and Norwegian Schools of Music and Performing Arts offer similar instrumental education for their users, in Poland there is also a highly specialised system of music schools providing goal-oriented professional tuition for young people at all educational levels. Analysis of the target groups and curriculum frameworks reveals that the concept of music school is understood differently in the two countries. Polish music schools prepare students to become musicians and do not serve as a leisure activity, in contrast to Norwegian Schools of Music and Performing Arts, which do not make strict demands of commitment and goal-oriented participation. Poland’s system is more structured and standardised, potentially leading to high levels of technical and musical proficiency, while Norway’s system is more flexible and inclusive, promoting broader educational and personal development goals.

Keywords: instrumental music education, comparative music education, music schools, instrumental students

Introduction

In many European countries, specialised instrumental[1] education takes place outside schools (De Vugt, 2017). There are public or privately funded music schools that provide instrumental tuition at different levels, besides classes in music theory, harmony, aural training, and other subjects. The accessibility of this type of music education varies to a relatively great extent across Europe. In some countries, instrumental education is free for all who apply, while in others there are entrance exams to assess the musical ability of prospective pupils. Tuition can be free of charge in some systems, while in others it might be quite expensive, and less accessible for that reason (De Vugt, 2017).

The focus on regional differences has significantly influenced the development of comparative education during the last decades (Mitter, 2009). As a result, the attention is often on the geographical, institutional, and thematic landscape of Europe, with its unique working environments. Traditionally, comparative studies and projects have focused heavily on comparing national education systems and issues (Mitter, 2009). However, the scope is expanding to include the recognition of cultural configurations as significant subjects in comparative education (Crossley, 2009). Recent methodological approaches are increasingly geared towards predicting outcomes and being practically useful for policymaking, rather than merely describing and explaining phenomena (Phillips, 2006). This article aims to describe two different approaches to educational provision within non-compulsory music education. It combines an analysis of government documents with a broader examination of the organization and availability of such education as part of the cultural investment on the national level. This kind of comparison provides both policymakers and practitioners with a valuable source through which they can be informed about practice elsewhere (Phillips, 2006). Comparative research contributes to understanding one’s own education system by looking at those of others. It has the potential to uncover the hidden assumptions that underpin the systemic provisions. Additionally, it offers alternatives to the ways in which one has always done things (Burnard et al., 2008).

Comparison of music education can give music teachers a deeper understanding of the teaching approaches and of pedagogy in general (García & Dogani, 2011). There are many differences in how educational and cultural policies are put into practice in various countries. Music education has a significant impact on the development of young students, and especially one-to-one tuition, which seems to be a common way of organising instrumental lessons in many European countries (García & Dogani, 2011). Kertz-Welzel (2004) highlights that a major issue with most comparative music education research is its tendency to cover entire systems, often neglecting specific details. The aim of this article is to shed light on some aspects of two different public systems offering professional instrumental education to children: the Norwegian system, focusing on Schools of Music and Performing Arts, and the Polish system, focusing on first-degree Music Schools, with comparison of target groups, organisation and competence aims.

Music education across Europe

An extensive comparison of music education in 20 European countries was conducted by Music education Network (meNet): A European Communication and Knowledge Management Network for Music Education, funded by the European Commission as part of the SOCRATES-COMENIUS programme run in 2006-2009 (De Vugt, 2017). Available results of the meNet research project seem to focus on music subjects in compulsory education, as well as music teacher education, and provide extensive comparative information in this field (Rodríguez-Quiles, 2017). The researchers involved in mapping music education systems across Europe stress that, although the report describes music education in the different European countries based on official documents, the knowledge and experience of individual teachers, and each country’s situation, more research in this field is needed, especially using in-depth methods (De Vugt, 2017; García & Dogani, 2011). Moreover, the survey data reveals that the study of music in schools, demonstrated through education policies and expressed in national curricula, may in some cases differ from the actual content of the music or instrumental lessons. It is not always the case that “curriculum in practice” closely reflects the written curriculum (García & Dogani, 2011). Dogani (2004) suggests that the reason for this may be the use of the curriculum guidelines, the teachers’ individual areas of expertise, and their personal educational philosophy while teaching. The authors request research that addresses issues at the level of content, aims, concepts and approaches (De Vugt, 2017).

The area of interest is instrumental music education outside compulsory schooling. Norway and Poland were chosen as examples. Their systems seem to follow different visions, and they have different target groups, organisation structures and learning goals, which was the main reason for this choice. Another reason was to enable a broader view and a deeper understanding of general aspects of what is often called the East European music school system, as opposed to the Scandinavian system. An extensive research overview indicates that this kind of comparison of two diverse music education systems in Europe has not been conducted before. Additionally, the choice was based on personal in-depth experience with these two relatively different systems, both as a student, teacher and researcher, and being native/nearly native in both Polish and Norwegian, giving me the opportunity to analyse the documents solely available in these languages.

The research question explored in this article is: How is the instrumental education system organised in Norway and in Poland, what is the content of the curriculum framework and what consequences might the chosen organisation form and vision have for users?

Method

This article is based mainly on analysis of available legal documents, both governmental (education acts, national curriculum frameworks) and those published by relevant national, municipal and local arts councils and centres in each country, as well as statistical analysis of the accessibility of non-compulsory instrumental music education. The focus is on primary and, to some extent, secondary music education. The relatively exhaustive description of the curriculum frameworks aims to show the detailed level of regulations for the different school types. This reflects the degree of freedom to choose the organisation of instrumental education, the teaching approach, the content of lessons and the target group. A general comparison of the main aims and availability of instrumental education alone would give a narrow and less informative picture of the opportunities for musical development when enrolled in the respective systems.

The preliminary analysis of legal documents, primarily the Framework Teaching Plans for Artistic Public Schools and Institutions (Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, 2023) in Poland, and the Framework Plan for Schools of Music and Performing Arts (Norsk Kulturskoleråd, 2025) in Norway, shaped the conceptual framework utilized in this study. Both documents systematically describe the curriculum framework, competence aims, (recommended) organization forms, and the target group. Selected elements of the comparative case study approach (Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017) were used in the analysis. This approach focuses on tracing the phenomenon of interest across different sites and scales. In the current study, the emphasis was placed on examining policy formation and appropriation across micro-, meso-, and macro-levels, referred to as “vertical analysis” by Bartlett and Vavrus (2017). This study examined two non-compulsory music education systems, comparing three levels: policymaking (macro-level), organization of the systems (meso-level), and the possible consequences for the users (micro-level).

The analysis generated side notes to interpret various statements and identify overarching themes. They were then organized around key concepts and grouped into four categories:

· Educational goals

· Target group

· Organisation and accessibility

· Curriculum framework and competence aims

The comparison of the categories across these two cases highlighted several interesting aspects and revealed some similarities, as well as major differences between the systems. It placed the descriptions into a broader social context, which is elaborated on in the discussion section.

The analysis of the legal documents was supplemented with the latest accessibility statistics. However, crucial statistical information about an important segment of the Polish system, specifically data on music centres, was unavailable. Statistics Poland (GUS) was contacted via email. GUS confirmed that their databases on the Central Statistical Office Information Portal do not contain information on music centres and that they have no data on the number of entities or participants enrolled in these educational institutions. The information about music centres and other cultural institutions in Poland was gathered through the analysis of (limited) scientific publications on this topic and the websites of several music centres, established both in big cities and rural areas.

The music education system in Poland

The music education system in Poland was established after World War II. Instrumental or vocal music education is provided mainly by the public system of music schools and music centres. The public music schools in Poland are free of charge, while the private alternatives, which are obliged to follow the same state school laws and curriculum framework and offer the same content in an education cycle, can be relatively expensive (Nogaj, 2023).

Educational goals and the target group

The primary goal of Polish public music schools is to educate students to a professional standard and give them the opportunity to become musicians. In a general sense, the network of music schools provides an opportunity to detect, develop and support musical talent and the interests of children and young people, besides ensuring intensive instrumental education and the most favourable conditions, under the supervision of highly qualified musicians, free of charge (Jankowski, 2012; Nogaj, 2023).

Public music schools play an important role in local society, cooperating with the immediate social environment in creating educationally valuable cultural programmes. The schools are responsible for organising concerts and other events, as a motivating model of how to perform (western classical) music. Music schools are an area of artistic experience for the entire school environment and for local society (Jankowski, 2012).

Organisation and accessibility

Instrumental specialised music education in Poland has a three-stage structure. It covers education at the level of a primary music school, a secondary music school, and at the level of music colleges. Both first- (primary) and second (secondary)-degree music schools are supervised by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage with the help of the Artistic Education Centre. The Ministry provides a detailed description of the organisation of the schools, who can apply, what specialties are available to the students and the content of the curriculum (Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, n.d.).

Music education at the primary level is provided by:

· First-degree music schools – schools with a six- or four-year education cycle, depending on the student’s age while applying (6-16), providing only artistic education. The lessons take place during afternoons and/or weekends, several days/hours every week.

· First-degree general music schools – schools with an eight-year education cycle[2], which provide integrated education in the field of both the compulsory primary school curriculum and artistic education. Only children aged 6 or 7 are admitted to this type of school.

Children applying for admission to the first-degree music school undergo an aptitude test. The test mainly involves checking general musical abilities (sing a melody, distinguish between high and low pitches, repeat rhythm patterns, etc.), psychophysical conditions and predisposition to learn to play a specific instrument. Instrumental lessons are held individually (one student – one teacher). The student also attends compulsory weekly group activities, including eurhythmics, ear training, music theory, instrumental ensembles, orchestra and choir.

Music education at the secondary level is vocational, provided by:

· Second-degree music schools – schools with a six- or four-year education cycle, depending on the educational specialisation, providing only artistic education. They enable students to obtain the professional title of musician after passing the diploma examination. Students between 10 and 23 years of age may apply.

· Second-degree general music schools – schools with a six-year education cycle, providing integrated general and artistic education at the secondary level. The students obtain the professional title of musician after passing the diploma examination, and a secondary education certificate after passing the secondary school leaving examination. Candidates who are under 14 years of age and have completed first-degree music school may apply.

Candidates applying for admission to a second-degree music school take an entrance examination, including the performance of several pieces on their main instrument, and an examination in ear training and general musical knowledge, at the level required at the end of the first-degree music school curriculum.

In the 2023/24 school year, music education was provided by 465 (including 55 general) first-degree music schools, educating 65,000 students. Many of these institutions (83.2%) were public schools, while 15.1% were non-public schools with public school rights, and 1.7% were non-public schools (GUS, 2024a) Vocational music education was offered by 224 second-degree music schools (including 107 general), providing music education to 24,000 students (1.4% of all students taking upper secondary education). Many of the institutions were public schools (80.8%), attended by 88.5% of the students (GUS, 2024a). Given that around 3 million students were registered in the Polish education system, it appears that around 3% of them attended music school in the 2023/24 school year.

Curriculum framework

Poland has a national curriculum framework for artistic education, approved by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, which music schools are obliged to follow. It regulates both the number of hours spent on each subject during the education cycle and the content that must be covered and assessed. This means that each music school student receives relatively the same instrumental and theoretical education, regardless of where the student lives in Poland. Private schools are expected to meet the same basic requirements.

Table 1. Compulsory educational activities in first-degree music school, six-year education cycle (Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, 2023).

|

|

Compulsory educational activities |

Weekly number of minutes in the classroom |

|||||

|

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

VI |

||

|

1 |

Main instrument* |

60 |

60 |

60 |

90 |

90 |

90 |

|

2 |

Piano – second instrument |

- |

- |

- |

- |

30 |

30 |

|

3 |

Eurythmics |

90 |

90 |

90 |

- |

- |

- |

|

4 |

Ear training |

45 |

45 |

45 |

90 |

90 |

90 |

|

5 |

Accompaniment |

** |

** |

** |

** |

** |

** |

|

6 |

Musical knowledge |

- |

- |

- |

45 |

45 |

45 |

|

7 |

Choir, orchestra, chamber music |

6*** |

|||||

* Main instrument and second instrument piano lessons are conducted individually.

** Work with an accompanist lasts an average of 15 minutes a week per student.

*** Choir, orchestra or instrumental group classes are conducted accordingly to the students’ level of advancement. The number of groups is determined by the school principal.

Table 1 is an example of this regulation, showing the teaching hours in first-degree music schools, in a six-year education cycle (Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, 2023). Similar detailed regulations are provided for all types of music schools.

Competence aims

The Ministry provides a detailed description of the content of all subjects for each grade, as the main instrument, piano as a second instrument and the theory classes. The curriculum framework describes learning goals for each instrument. Each of the learning goals is then defined extensively. Below is an example of general learning goals for main instrument piano after six years of music education (Table 2), and a more detailed description of one of them: basic instrumental skills (Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, 2023). All the other learning goals are described in a similar way.

Table 2. The general learning goals for the subject main instrument piano after completing first-degree music school in Poland (Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, 2023).

|

Learning goal |

Description |

|

Basic musical knowledge |

The student knows the basic history of the instrument, the structure of the instrument and its parts, the basic theory of tonal music, rhythm, musical notation, formal structure of the pieces, knowledge about the periods and composers. |

|

Basic instrumental skills |

The student acquires the ability to properly use the playing apparatus by presenting the correct posture, hand position, appropriate way of producing sound, various articulations and use of the pedal; develops skills in using basic piano playing techniques; shapes the ability to properly implement homophonic and polyphonic texture, plays scales and arpeggios, transposes simple musical structures. |

|

Shaping aesthetic sensitivity and sense of beauty |

The student develops skills in musical interpretation consistent with the style and character of the formal structure of works; masters piano literature in its basic musical forms and styles; and acquires the necessary skills to perform correctly during the recital at the end of the educational stage. |

|

Independent learning of music pieces |

The student knows the rules of notation of piano music; reads the musical text independently; acquires the ability to correctly sight-read easy pieces; independently learns simple musical works using suitable technical skills and musical knowledge. |

|

Independent practice |

The student improves performance correctness and shows the ability to correct his/her own mistakes during unsupervised practice. |

|

Playing together with others |

The student develops musicality through playing with others; applies knowledge and musical skills correctly while playing for four hands, two pianos, or with another instrumentalist. |

|

Performance abilities |

The student develops the ability to play prepared pieces on the piano in front of an audience; demonstrates the ability to concentrate on a musical task and overcome stage fright; gets to know and learns how to use various ways of mastering pieces by heart; acquires knowledge and practice in stage performance; develops proper self-assessment of the works performed. |

The learning goal of basic instrumental skills is extensively defined in the following way. The student:

· Extracts and shapes the sound according to the character, dynamics and register of the piece

· Uses the playing apparatus while maintaining correct posture (height, seat distance, leg position), freedom and flexibility of the motor system, joint flexibility, proper positioning of hands and fingers, even finger movement, fingertip grip activity, hand coordination and independent work of hands and fingers

· Uses basic playing techniques in practice at moderate tempos: finger, arpeggio, two-note, chord and cantilena

· Plays with various ways of articulation: portato, legato and staccato

· When playing the piano, correctly produces homophonic and polyphonic texture while maintaining a sound relation of the main melody and accompaniment, linear hearing in two-voice polyphony and the beginnings of three-voice polyphony

· Uses the right pedal properly: rhythmic and syncopated

· Correctly plays major and minor harmonic and melodic scales and arpeggios up to five key signs, tonic arpeggios with inversions, arpeggios based on four-note dominant seventh chords and diminished seventh chords without inversions, cadences and chromatic scales

· Transposes simple melodies and other musical structures (e.g. cadences) to various keys

The group/theory classes (ear training, eurythmics and others) must follow a yearly plan of topics and learning goals. The progress of the students is formally assessed once or twice a year, in the form of graded exams, recitals and tests, ensuring that all the necessary knowledge and skills have been acquired at each level of education.

Music centres and other cultural institutions

The music centres (ogniska muzyczne in Polish) are easily accessible institutions providing instrumental tuition. They are run by either the state, municipalities, musical and artistic non-profit societies, communities or local private cultural entities. They are intended for students who want to start their adventure with music, or continue it, but do not plan a greater commitment. Music centres enable musical education at the basic level and offer individual instrumental lessons, usually twice a week for 30 minutes (Osrodek Edukacji Muzycznej, 2025), and group lessons in music theory, ear training and eurythmics once a week. Unlike music schools, there is no age limit for applying and attendance. Recruitment of students is based on the principle of maximum availability (Pliszka, 2024). The music centres offer both classical and popular music classes. At many of the centres participants can choose to be enrolled in either the system with formal assessments, exams, theory classes and a completion certificate at the end of the six-year course, or the system without formal assessment. The programme is then adapted to the student’s individual capabilities and music theory classes are not compulsory. After completing the course with no exams, participants receive a certificate of attendance at a music centre (Warszawskie Towarzystwo Muzyczne, 2025).

Music centres aim to make learning music available to everyone in society. They were originally a new way of providing music education to workers and peasants in rural areas and small communities in Poland under communist rule (Pliszka, 2024). In 1958, the People’s Music Institute (LIM) was assigned the task of unifying their structures and programmes (Bojus, 1972). Since then, they have usually adhered to the main structure of the curriculum framework of the music schools, but take a broader approach (Warszawskie Towarzystwo Muzyczne, 2025). Many of the activities take place in the primary schools’ buildings, serving as a leisure activity for children living nearby. Tuition at the public music centres is free of charge, while tuition at the music centres run by non-public institutions (often receiving some public funding) or private institutions (with no external funding) is usually not free of charge.

Music centres often organise musical life in the community. Another function is planning concerts, lectures, performances, and meetings with composers and musicians. They cooperate with each other and with cultural-educational organisations on arranging numerous non-profit music activities (Bojus, 1972; Jankowski, 2012; Warszawskie Towarzystwo Muzyczne, 2025).

There appears to be no statistical data providing information about the number of music centres or their attendees. Statistics Poland provides information about 3678 public cultural centres, with 452,638 registered participants taking part in educational artistic activities in 2023 (GUS, 2024b). Apart from music centres, this number assumingly includes other local institutions, e.g. so called “houses of culture”, providing music and arts education as a leisure activity (Kuciapiński, 2012). The most frequently mentioned forms of music activities include vocal, instrumental and vocal-instrumental groups, choirs, children’s brass bands, folk bands. Some institutions run jazz groups or big bands (Dymon, 2015). Most institutions offer lessons in playing instruments. 81% of the instructors are teachers with higher music education. The rest are teachers with higher education who graduated from music schools and often have qualifications considered to be similar (Dymon, 2015). The participants often take part in festivals, annual festivities, or competitions and form an important part of local music education and culture. It is reasonable to believe that more children (apparently several hundred thousand) are enrolled in instrumental courses run by music centres and houses of culture, than by music schools.

The music education system in Norway

Instrumental or vocal music education in Norway is provided mainly by the non-compulsory Schools of Music and Performing Arts, run by the municipalities. Other important providers of instrumental music education across the country are school wind bands. The alternative at secondary level is the Music, Dance and Drama general study programme at upper secondary school. Below is a description of these three types of institutions providing instrumental tuition at different levels, focusing on music schools.

Educational goals and the target group

Norwegian non-compulsory Schools of Music and Performing Arts (SMPAs, kulturskole in Norwegian) aim to give all children and young people access to relevant and differentiated art and cultural education of high quality in a safe and good school environment (Norsk Kulturskoleråd, 2025). Additionally, they seek to ensure that children and young people have access to specialisation in the arts, which can qualify then for upper secondary and higher artistic education. The mission of SMPAs is to provide activities that make it possible to learn, experience, create and convey cultural and artistic expression. The introduction to the curriculum framework (Norsk Kulturskoleråd, 2025) states that the schools contribute to education, to promoting respect for one’s own and others’ cultural belonging, to awareness of one’s own identity and to developing an ability for critical reflection. It stresses the goal of providing music and art education for everyone.

Organisation and accessibility

SMPAs are integral to Norway’s public education system and local cultural life (Norsk Kulturskoleråd, 2016). Admission is open to all applicants, although some may face long waiting periods. There are no entrance auditions or aptitude tests (Vinge & Westby, 2021). Funding for SMPAs comes primarily from the municipalities (over 70%), with additional contributions from users (22.3%) and external sources (4.6%). Families on low incomes can apply for reduced rates or free places (Berge, et al., 2019). The main target group is children from 6 years of age. The majority of SMPAs set the upper age limit at 20 years, or the year the pupil ends secondary education.

The first public music schools appeared in the 1960s. Since 1997, these schools have been governed by Section 26-1 of the Norwegian Education Act, which mandates all municipalities to offer courses in music and other cultural activities for children and young people, integrated with the school system and local cultural life (Opplæringslova, 2023). In the 2024/2025 school year, 74,848 students (approx. 8% of the students registered in the Norwegian education system) were enrolled in music courses at 252 SMPA (Utdanningsdirektoratet, 2024b).

Curriculum framework

SMPAs aim to provide a broad range of professional and pedagogical courses. The curriculum framework, entitled Diversity and Deeper Understanding (Norsk Kulturskoleråd, 2016), includes specific curricula for various arts disciplines and categorises courses into three training programmes with distinct profiles and objectives. The document is written by the Norwegian Culture School Council, and it is not mandatory to follow it. The curriculum framework for SPMAs is a recommendation to be used as a guide for local politicians, school principals and teachers, but it does not oblige the school owner to apply the content in any way. The recently published general part of a new curriculum framework, with the title Culture School for Everyone (Norsk Kulturskoleråd, 2025), stresses the importance of reflecting the diversity of cultural expressions and cultural identities in the multi-cultural society, and it facilitates an inclusive school.

The authors of the curriculum framework state that for the vision of a culture school for everyone to have real content, the school’s practice is recommended to be organised within three areas, with different profiles and objectives (Norsk Kulturskoleråd, 2025).

The Breadth programme: open admission programme with focus on developing creative skills, artistic and cultural competence, and interpersonal skills as a foundation for personal expression. It includes group and ensemble instruction, such as play-based rhythm beginner groups in music, classes for special needs students, or groups combining different art disciplines.

The Core programme: open admission programme for students motivated to make systematic individual efforts, offering one-to-one instrumental tuition or group lessons in other artistic disciplines. It includes both beginner and advanced levels, aiming to qualify students for upper secondary education. The programme is long-term.

The Depth programme: this programme requires auditions and targets highly skilled students with qualifications for specialisation in an arts discipline. It is more extensive than the Core programme, demanding a high level of determination and individual effort. The Depth programme can qualify students for upper secondary and higher education in music.

SMPAs are recommended to organise their courses using the general curriculum framework, adapted to their local resources, including the number of pupils, teacher qualifications, finances and potential cooperation with other institutions. Consequently, there are significant differences between schools across the country. Most schools offer the Breadth programme in music for the youngest students, where they learn basic musical knowledge, experiment with different instruments, or experience music and art in weekly group lessons. The Core programme includes individual lessons on a chosen instrument (20-30 minutes once per week), and some schools also offer band and orchestra lessons as part of this programme (Berge, et al., 2019). There are no formal assessments or requirements; teachers and students collaboratively decide on the repertoire and learning progression, using both classical and popular music. The focus is on the pleasure of making music as much as on musical and technical development, allowing students to learn at their own pace and play music that motivates them. There are no music theory or ear training lessons.

About half of the SMPAs offer a Depth programme. Students in this programme attend theory and chamber music lessons, concerts and master classes regularly, in addition to weekly 40-minute to one-hour individual instrumental lessons. These courses may be organised in cooperation with other regional or national arts institutions (Berge et al., 2019).

Competence aims

The curriculum framework (Norsk Kulturskoleråd, 2016) provides recommended competence goals. The schools should ensure that all students utilise their potential as far as possible. The music learning approach used in Norway suggests that all young people have inherent potential for singing and playing an instrument.

The curriculum framework does not provide learning goals for each instrument. It lists five general key competences for music students. The authors stress that the key competences represent a long-term view of learning, and that they are the key to success, no matter what level the student is at. Table 3 gives an overview of key competences in music (Norsk Kulturskoleråd, 2016).

Table 3. The five key competences for instrumental education at Norwegian Schools of Music and Performing Arts (Norsk Kulturskoleråd, 2016).

|

Key competence |

Description |

|

Practice |

Practicing teaches students to be their own teachers by planning, rehearsing, listening critically, and giving constructive feedback. The goal is to perform music with full dedication, requiring significant time commitment |

|

Perform |

Performing involves deep expression, communication, concentration, presentation, stress management, recording, and concert production. This applies to solo and group performances with various ensembles and musicians. |

|

Hear |

Hearing involves listening, analysing, interacting, imitating, and improvising with voice, instruments, dance, and movement. It also includes transcribing music, critically listening to one’s own playing, and appreciating music. |

|

Read |

Reading music involves perceiving, interpreting, and understanding basic elements like signs, motives, themes, and form progressions from notation, then recreating them. This helps develop an understanding of how structures shape musical expression. |

|

Create |

Creating involves intuitive improvisation, composition, songwriting, sharing musical ideas, and developing skills in sound design, music technology, and concert production. Mastering notation and managing self-composed music is essential. |

The core programme is divided into four levels: elementary, intermediate, late intermediate and advanced. The levels are only a suggested progression for teachers. The education programme is “linear” in practice, as there is no assessment of any kind along the way. Nevertheless, the authors of the curriculum framework suggest which learning goals can be utilised at each level. I have chosen the early intermediate level as an example:

The student at the early intermediate level:

· Imitates musical form and expression

· Improvises based on different scales and chord progressions

· Listens actively to his/her own play and learns in interaction

· Uses triads, scales and intervals as notation tools

· Sight-reads simple pieces

· Reads, interprets and applies music theory and background history in the rehearsal process

· Composes his/her own melodies for his/her instrument

· Composes music using simple music technology

· Has basic technical knowledge of the instrument

· Practices in various ways and is solution-oriented

· Plays at concerts in various audience arenas

The teachers who choose to follow the recommendations listed above must cover all the topics during the weekly instrumental lessons, as there are no theory classes in the Core programme (Berge, et al., 2019). Since the schools do not require any form for assessment and the curriculum framework is not a legal act, the teachers can freely choose the content of the lessons together with each of their students. Some recent research results suggest that relatively few teachers try to cover more than the basic reading and playing skills during the lessons (Leikvoll, 2024). At the same time, the majority of the SMPAs adhere to the recommended organisational system and the vision stated in the curriculum framework.

Upper secondary music education

Upper secondary education in Norway is intended to qualify students for either working life or higher education. It is split into two main routes: vocational study programmes and general study programmes (Utdanning.no, 2025).

General study programmes provide a basis for studying at college or university and usually include three years of education. Students can choose between five different programmes, one of them being Music, Dance and Drama (MDD). All public education in Norway is open to all young people. Public upper secondary schools offering specialisation in music are obliged to give open access to all young people applying, whatever their musical skills and knowledge. The entrance auditions are voluntary, but they make it possible for highly skilled young musicians to receive additional points. Together with the points earned through grades from lower secondary school they constitute the ranking of the applicants. There are no requirements regarding musical knowledge and instrumental skills. At some schools, the emphasis is mainly on grades, while at others the instrument skills are highlighted.

As a consequence, students with no musical skills or knowledge may be offered a place on this programme, solely based on their (high) grades from lower secondary school. Hence, the level of musical competence of the students enrolled in the MDD programme may vary between the schools and between individual students. Inadequate grades in general subjects at lower secondary school level might prevent specialisation in music at upper secondary level.

A student who enrols in a music programme must take courses in common core subjects, common programme subjects, and elective programme subjects. The common programme subjects in year 1 include introductory courses in music, dance, and drama. while in years 2 and 3 they include direction and management, ergonomics and movement, music in perspective, and courses in instrument, choir or ensemble. Courses in elective programme subjects depend on the school offerings (Kunnskapsdepartementet, 2021).

The MDD programme is the only specialised music education programme in Norway that is obliged to follow the compulsory curriculum framework approved by the Norwegian Department of Education (Kunnskapsdepartementet). The curriculum framework regulates both the number of hours spent on each subject during the education cycle and the content that must be covered and assessed. Due to the students’ varying level of musical competence (from beginner to advanced), the description of expected learning outcomes is relatively general. Some examples of competence goals in the music specialisation subject (Kunnskapsdepartementet, 2021) are listed below.

Upon completion of Music specialisation 2 the student is able to:

· Recognise and explore elements and instruments in varied musical examples from oral and noted sources using music theoretical knowledge and listening

· Express musical intentions by using various musical instruments in improvisation, alone and with others

· Read notated music and notate music by listening

· Arrange and compose music for different ensembles by using knowledge of musical instruments and idiomatic features of various instruments

· Practice, perform and document one’s own arrangements and compositions

· Use various hardware and software in arranging, composing, sound recording, editing and mixing

In the 2024/25 school year, around 3,500 students were enrolled in MDD programmes with music as their specialisation, at 46 schools offering this programme in Norway, representing around 1.8% of all upper secondary school students (Utdanningsdirektoratet, 2024a).

School bands

In Norway there is a long and vibrant tradition for wind bands. In 2020, the Norwegian Band Association (NMF) had over 60,000 members of all ages playing in over 1,600 bands (Norges Musikkorps Forbund, n.d.). Playing in a wind band is one of the most popular recreational activities in Norway, and NMF is the country’s largest voluntary cultural organisation (Norges Musikkorps Forbund, n.d.). In most cases, music bands are based on the efforts of volunteers, and for school bands it is parents who organise and manage day-to-day operations, hiring conductors and teachers to run musical activities. A school band is attached to a school and a local environment, providing opportunities for children and young people who want to learn how to play an instrument in interaction with others. In 2024, there were over 1,000 school bands registered in the database of the Norwegian Band Association, with nearly 37,000 children attending weekly rehearsals, group lessons, festivals and competitions (Norges Musikkorps Forbund, n.d.). It seems that more than 37% of public schools have a school band (Utdanningsdirektoratet, 2024b), and 7% of school-age children play in such a band. Many children have been introduced to music by playing in school wind bands.

The work on inclusion of children from different cultures living in Norway is rooted in the organisation’s current strategy plan (Norges Musikkorps Forbund, 2022), which states that a wind band which is a member of the Norwegian Band Association must be an inclusive community with room for anyone who wants to participate. The band should be an arena for development of social competence across age, gender, religion, ethnic origin, and social background. This definition of inclusion underlines that every band member receives differentiated training together with others, participates actively in concerts and competitions, and experiences mastering and belonging. There is no audition, entrance test or any form of assessment of the candidates. School bands are open to every child who wants to learn to play an instrument. The band provides the instrument, the music and other necessary equipment free of charge for the participants. The music to be used is arranged by the conductor in a way that makes it possible for everybody to participate actively, regardless of their level of musical skill. The school bands are financed by the voluntary work of the members and of their parents, and by government support programmes, as well as the support of private and public foundations and agreements. The bands’ boards (consisting mostly of the parents of the participants) often collaborate with the local SMPAs, to ensure well-qualified conductors and instrumental teachers for the band members. The school bands rehearse once or twice a week for about two hours, in the afternoons. The participants may be offered additional instrumental lessons, either individually or in small groups.

The school bands have no curriculum framework or other formal or informal documents describing the content, progression, or expectations. The majority of the school bands participate actively in numerous local, regional, national, and international competitions each year, for both entire bands, smaller ensembles and soloist members (Norges Musikkorps Forbund, n.d.).

Discussion

Both Polish and Norwegian public music education systems present an affordable opportunity to learn to play an instrument and develop musically for several hundred thousand children every year. They offer tuition at both basic and advanced levels, giving the participants a wide range of opportunities: from a meaningful leisure activity to mastering an instrument at a professional level. Nevertheless, there are several major differences, which challenge the general aim of equal opportunities for musical development for all children across society.

Analysis of the target groups, as stated in available public documents, shows that the concept of music school is understood differently in the two countries. Children enrolling at a music school in Poland are required to demonstrate commitment, and mental and physical effort, from the very beginning. The school prepares the students to become musicians.[3] Polish music schools do not serve as a leisure activity, in contrast to Norwegian schools, which do not make the same demands of commitment and goal-oriented participation. Several Polish music centres address this issue. Osrodek Edukacji Muzycznej explains on their website (my translation):

In Western European countries, this form of education is called a music school, because according to logic, learning takes place at school, and music learning takes place at a music school. In Poland, however, learning to play an instrument without separate additional and autonomous subjects in the field of music theory functions under a name of music centre (Osrodek Edukacji Muzycznej, 2025).

In terms of target group and organisation, music centres in Poland have a similar position to Norwegian SMPAs. It is therefore misleading to compare music school systems in these countries – but we can compare (instrumental) non-compulsory music education systems.

Accessibility and the target group

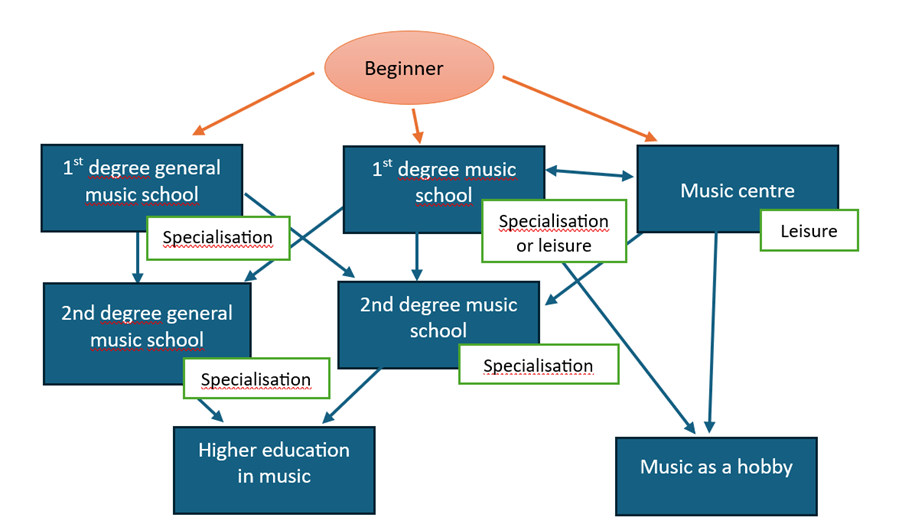

In Poland, students receive focused music education from a young age, potentially leading to a high level of proficiency. The system focuses on early specialisation, as shown in Figure 1. Entrance exams may create barriers for some children, limiting access to those who pass the tests. However, music centres are a relatively easily accessible alternative to the goal-oriented music education programmes in a public music school system. For those who choose to enrol in specialised music education, there seem to be clear pathways leading from primary, through secondary, to higher education in music.

Figure 1. The instrumental music education system in Poland.

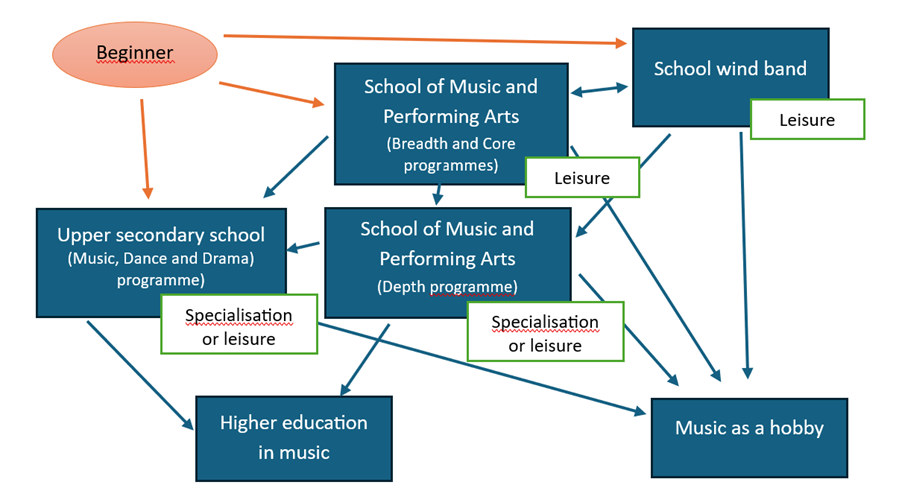

Norway’s system seems to be more inclusive and integrated with general education and local culture, promoting broader educational and personal development goals (Figure 2). Children can attend music education programmes without the pressure of entrance tests or formal assessments during the education cycle. There is emphasis on cultural education and personal development, and not just musical proficiency. The great popularity of music schools, especially in cities, may result in some children facing long waiting times for admission.

It is important to mention that the graduation from a music school is not necessary to be accepted to higher education in music, neither in Poland, nor in Norway. In both countries there are entrance examinations, containing performance audition and music theory tests, allowing students with satisfactory level of knowledge and skills to enrol in music education at the university level.

Figure 2. The instrumental music education system in Norway.

The challenge of having fewer places than candidates in the music education system is resolved in different ways: while in Poland there is selection of children who can potentially achieve a higher learning outcome (the musical aptitude test), there are waiting lists in Norway, with the date of application as the only ranking criterion. Polish music centres in highly populated areas also operate with waiting lists, while Norwegian school bands usually take in all applicants.

Both Norwegian SMPAs and Polish music centres offer tuition at beginner and advanced level. However, music centres seem to offer at least twice as intensive individual instrument tuition as SMPAs, and, unlike Norwegian schools, music theory and ear training lessons are available from beginner level. Polish music schools focus on professional music education. Attendance is time-consuming, demanding a high level of motivation and effort. At SMPAs, only the Depth programme, directed at students who already show a high skill level, offers longer instrumental lessons, and music theory classes. In Norway, there seems to be limited opportunity to enrol in specialised music education, with a final goal of becoming a musician, before the age of upper secondary education (from 15 years).

It is reasonable to believe that children enrolled in the Polish system, with early specialisation, can potentially achieve greater proficiency in music than children schooled in the Norwegian music education system. It is important to mention that some of the Norwegian students combine music school lessons with participation in a school wind band, which can give them significantly greater opportunities for musical development and experience. Table 4 summarises the opportunities for different types of music education in Poland and Norway.

Table 4. Access to specialised music education and music as a leisure activity in Poland and Norway.

|

Education cycle |

Professional specialised music education |

Music as a leisure activity |

||

|

|

Poland |

Norway |

Poland |

Norway |

|

Primary |

yes |

no |

yes |

yes |

|

Lower secondary |

yes |

limited |

yes |

yes |

|

Upper secondary |

yes |

yes |

yes |

yes |

Curriculum framework

The general level of the students and the level of difficulty of the vocational subjects in Polish music schools is high. It is not possible to enrol in specialised music education at secondary level without several years of instrumental and theoretical training. Students receive the same education, regardless of location, ensuring a standardised level of music education across the country. Learning is structured, with clear and detailed learning goals, which provides a mandatory list of the content of lessons for students and teachers. High expectations, including rigorous assessments, may create pressure, but also ensure high standards.

The Norwegian music education system is flexible and inclusive, with adaptable learning goals highlighting individual needs and promoting personal growth. The curriculum framework focuses on overall musical and personal development, rather than technical skills. The absence of formal assessments and specific learning goals has several consequences. It may reduce stress, but on the other hand, it leads to variation in the level of musical and technical development of the students, as proficiency in an instrument is not a priority of the system. At the same time, teachers have the freedom to tailor lessons to individual students, facilitating diverse educational experiences.

Learning goals

The learning goals in Polish music schools focus strongly on technical and musical proficiency, precision and broad knowledge. Key aspects of music education include the knowledge necessary to develop and play the instrument consciously, ear training, and music theory and history, as well as participation in musical life, presenting achievements in public (Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, 2023). The learning goals both in SMPAs and MDD secondary school programmes in Norway are more holistic and focused on creativity. Key aspects include musical expression, improvisation, active listening and performance (Norsk Kulturskoleråd, 2025). Students in Poland are likely to develop strong technical skills and precision in their playing, while the Norwegian curriculum framework encourages students to explore creativity by working with different genres, and by cooperating with the teacher in choosing repertoire and educational pathway.

Governmental supervision

Polish music schools are heavily regulated by governmental documents. Annual statistical information is exhaustive and accessible. There are reports and research articles describing different aspects of music schools. Music centres, on the other hand, do not seem to be supervised by any entities. Neither a national policy for this type of educational institution nor statistical information is available. Music centres do not have a national curriculum framework. However, many of them seem to utilise the main outlines from the documents available for the music schools (Osrodek Edukacji Muzycznej, 2025; Warszawskie Towarzystwo Muzyczne, 2025). Absence of national data of any kind may suggest that instrumental education which does not lead to professional level is not of political interest in Poland. Norwegian SMPAs on the other hand, seem to be an important aspect of cultural education, approved by the government in the Education Act. The Culture School Council (Norsk Kulturskoleråd) is a national advisory board, working on unifying, researching, and constantly developing the schools’ offering and curriculum framework.

There appears to be no data stating how the written curriculum is used in practice. Standardised mandatory formal assessment at Polish music schools might indicate the expected consistency between the written guidelines and the actual content of the lessons. The absence of this type of national mandatory standards in Norway may give scope for free use of the curriculum framework. This assumption is confirmed in some recent research results (Leikvoll, 2024). This is why it is not possible to compare the actual level of proficiency, musical development, and learning outcomes of the students in each system.

Conclusion

While Polish music centres and Norwegian Schools of Music and Performing Arts offer similar instrumental education for their users, in Poland there is also a highly specialised music school system, providing goal-oriented professional tuition for talented young people at all educational levels. Poland’s system is more structured and standardised, potentially leading to high levels of technical and musical proficiency, while Norway’s system is more flexible and inclusive, promoting broader educational and personal development goals.

The choice of not including any form for more hermeneutic or interpretive approaches is undoubtedly a limitation of the present study. The nature of teaching and learning is culturally embedded (Burnard et al., 2008). The practitioners’ perspective might shed light on how the music education system in each of the countries influences expectations, goals, educational choices and learning outcomes. A follow-up of this study, using interviews and observations, can give a more in-depth view of the systems. Nevertheless, I hope that the analysis provided in the article may be a valuable source of information for policy debates concerning the pros and cons of early specialization versus broad access, talent development versus universal participation, and the role of arts education in society.

References

Bartlett, L., & Vavrus, F. (2017). Comparative Case Studies: An Innovative Approach. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education (NJCIE), 1(1). https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.1929

Berge, O. K., Angelo, E., Heian, M. T., & Emstand, A. B. (2019). Kultur + skole = sant: Kunnskapsgrunnlag om kulturskolen i Norge (TF-rapport nr.. 489). Telemarksforskning. https://www.telemarksforsking.no/publikasjoner/kultur-skole-sant/3487/

Bojus, J. E. (1972). Music Education in Poland [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Miami. Burnard, P., Dillon, S., Rusinek, G., & Sæther, E. (2008). Inclusive pedagogies in music education: a comparative study of music teachers’ perspectives from four countries. International Journal of Music Education, 26(2), 109-126. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761407088489

Crossley, M. (2009). Rethinking context in comparative education. In R. Cowen & A. M. Kazamias (Eds.), International handbook of comparative education (pp. 1173-1187). Springer.

De Vugt, A. (2017). European perspectives on music education. In J. Rodríguez-Quiles (Ed.), Internationale Perspektiven zur Musik (lehrer) ausbildung in Europa (pp. 39-58). Universitätsverlag Potsdam.

Dogani, K. (2004). Teachers’ understanding of composing in the primary classroom. Music Education Research, 6(3), 263-279. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461380042000281721

Dymon, M. (2015). Muzyczna edukacja poza szkolnym systemem nauczania [Conference presentation]. EAS Visegard Doctoral Conference, Prague. https://czechcoordinatoreas.eu/DOCS/Teorie-a-praxe_HV_IV_2015.pdf#page=22

García, J. A., & Dogani, K. (2011). Music in schools across Europe: analysis, interpretation and guidelines for music education in the framework of the European Union. In A. Liimets & M. Mäesalu (Eds.), Music Inside and Outside the School (pp. 95-122). Peter Lang.

GUS. (2024a). Edukacja w roku szkolnym 2023/2024. https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/edukacja/edukacja/edukacja-w-roku-szkolnym-20232024-wyniki-wstepne,21,2.html

GUS. (2024b). Kultura i dziedzictwo narodowe w 2023 r. https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/kultura-turystyka-sport/kultura/kultura-i-dziedzictwo-narodowe-w-2023-roku,2,21.html

Jankowski, W. (2012). Raport o stanie szkolnictwa muzycznego I stopnia. M. a. D. Institute. https://nimit.pl/wp-content/uploads/files/Raport%20o%20stanie%20szkolnictwa%20muzycznego%20I%20stopnia.pdf

Kertz-Welzel, A. (2004). Didaktik of music: a German concept and its comparison to American music pedagogy. International Journal of Music Education, 22(3), 277-286. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761404049806

Kuciapiński, M. J. (2012). Pozaszkolne instytucje kulturalne wsparciem dla rodziny w sferze rozwijania aktywności muzycznej dzieci i młodzieży szkolnej. Pedagogika Rodziny, 2(3), 39-52.

Kunnskapsdepartementet. (2021). Musikk fordypning (MUS08‑02): Kompetansemål og vurdering. Utdanningsdirektoratet. https://www.udir.no/lk20/mus08-02/kompetansemaal-og-vurdering/kv559

Leikvoll, K. J. (2024). Bruk av komponering og improvisasjon i instrumentalundervisning på kulturskolen: tidstyv eller inngangsport til musikk-og notasjonsforståelse? Nordic Research in Music Education, 5, 67–89. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.23865/nrme.v5.6055

Ministry of Culture and National Heritage (2023). Framework teaching plans for artistic public schools and institutions. https://www.infor.pl/akt-prawny/DZU.2023.145.0001012,rozporzadzenie-ministra-kultury-i-dziedzictwa-narodowego-w-sprawie-ramowych-planow-nauczania-w-publicznych-szkolach-i-placowkach-artystycznych.html

Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. (n.d.). Kształcenie muzyczne. https://www.gov.pl/web/kultura/ksztalcenie-muzyczne2

Mitter, W. (2009). Comparative education in Europe. In R. Cowen & A. M. Kazamias (Eds.), International handbook of comparative education (pp. 87-99). Springer.

Nogaj, A. A. (2023). Psychological counseling services in music schools in Poland: History and current status. Musicae Scientiae, 27(4), 875-888.

Norges Musikkorps Forbund. (n.d.). Om Norges Musikkorps Forbund. https://www.korps.no/om-nmf

Norges Musikkorps Forbund. (2022). NMF Strategiplan 2022–2026. Norges Musikkorps Forbund.

Norsk Kulturskoleråd. (2016). Rammeplan for kulturskolen: Mangfold og fordypning. Kulturskolerådet.

Norsk Kulturskoleråd. (2025). Rammeplan for kulturskolen: Kulturskole for alle. Kulturskolerådet.

Opplæringslova. (2023). Lov om grunnskoleopplæringa og den vidaregåande opplæringa (LOV-2023-06-09-30). https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2023-06-09-30

Osloskolen. (2024). Musikk på Majorstuen. Osloskolen. Retrieved 28.January from https://majorstuen.osloskolen.no/fagtilbud/musikk-pa-majorstuen-skole/musikk-pa-majorstuen-skole/

Osrodek Edukacji Muzycznej. (2025, January 28.). Ognisko Muzyczne. http://karlowicz.waw.pl/o-szkole/ognisko-muzyczne/

Phillips, D. (2006). Comparative Education: Method. Research in Comparative and International Education, 1(4), 304-319. https://doi.org/10.2304/rcie.2006.1.4.304

Pliszka, R. (2024). Pozalekcyjna edukacja muzyczna w rozwoju ucznia na przykladzie instytucji upowszechniania kultury w Slupsku i Koszalinie. Zeszyty Naukowe Panstwowej Akademii Nauk Stosowanych w Koszalinie, 6(24), 28-49.

Rodríguez-Quiles, J. (2017). Internationale Perspektiven zur Musik (lehrer) ausbildung in Europa (Vol. 4). Universitätsverlag Potsdam.

Utdanning.no. (2025, January 14). Videregående utdanning. https://utdanning.no/tema/utdanning/videregaende

Utdanningsdirektoratet. (2024a, 24 January). Elevtall i videregående skole – utdanningsprogram og trinn. https://www.udir.no/tall-og-forskning/statistikk/statistikk-videregaende-skole/elevtall-i-videregaende-skole/elevtall-vgo-utdanningsprogram/

Utdanningsdirektoratet. (2024b). Grunnskolens Informasjonssystem: Kulturskole https://gsi.udir.no/app/#!/view/units/collectionset/2/collection/110/unit/1/

Vinge, J., & Westby, I. A. (2021). Vurdering for læring i kulturskolens rammeplan. In S. N. Karlsen & S. Graabræk (Eds.), Verden inn i musikkutdanningene. Utfordringer, ansvar og muligheter (pp. 103-120). Norges musikkhøgskole.

Warszawskie Towarzystwo Muzyczne. (2025, January 22). Ogniska Muzyczne. https://warszawskietowarzystwomuzyczne.pl/ogniska-muzyczne/