Sofie Ilsvard and Marie Østergaard Møller

General Practitioners’ Discretion of Preventive Needs

Abstract: This article examines general practitioners’ discretion in preventive contexts. Based on semi-structured interviews with 15 general practitioners, we examine how lifestyle is used in their discretionary practices in contexts of healthcare prevention. Despite common educational background and professional ideology, GPs’ do not share lifestyle and our analyses show that this matters to their discretion of patients’ need for lifestyle intervention. The correspondence between general practitioners’ preventive strategies and their own lifestyle preferences is interpreted as evidence of autonomy in general practice where general practitioners act relatively autonomously and differ in their interpretation of how preventive policies should be exercised in practice towards patients.

Keywords: discretion; lifestyle; health prevention and promotion; street-level bureaucrats; general practitioners

Many policies and interventions do not have clear policy goals or target populations leaving it up to the professional encountering the citizen to decide about the content and scope of public policy delivery. This leaves a large amount of discretion to the professional (Lipsky, 2010).

In this article, we explore how general practitioners (GPs) transform political intentions into concrete practices towards patients (Lipsky, 2010). Even though health prevention has been a salient issue on the political agenda in most Western countries since the 1970s (Lupton, 1995; Larsen, 2011) the area of health prevention and promotion suffer from being vaguely defined and muddled with unambitious (and underfinanced) political ideas (Zalmanovitch & Cohen, 2015). We choose to study the case of health promotion in Denmark, where the same vague idea of doing more health promotion and prevention persist as in other Western countries. The Danish Government has initiated a range of health promoting projects, nevertheless still within a vaguely defined regulative setting. In addition, the health policy at “the ground level” is a highly professionalized area, which gives us the opportunity to study discretion in a context with vague political and strong professional ideas. The general idea behind health promotion and prevention is that it is always better to prevent disease than to treat it, and where disease treatment obviously addresses patients’ diseases, disease prevention addresses lifestyle and risk factors associated with risky forms of behavior (Lupton, 1995, p. 51). Disease prevention is aimed at individuals who are (still) free of symptoms and is carried out by targeting lifestyle, offering ways to modify risky behavior, however, at the same time potentially compromising personal autonomy. Even though Denmark is often classified as a universal welfare state (Esping-Andersen, 1990)—we see examples from the health sector, where the Danish policy is aligned with more residual state behavior. For example, this is seen in the way the Danish Government perceives health as a condition associated with personal responsibility and hence subject to informed choice. Unhealthy behavior is thus perceived as a major cause of disease and related to individuals’ free choice (Vallgårda, 2001). This is especially true within the areas of diet, tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and physical activity (Regeringen, 2014).

Within the sociological professional literature, doctors are described as a dominant profession among the providers of health services. They hold a legitimate, monopolistic and social closured expert status as diagnosticians and decision makers on behalf of patients (Freidson, 1970/2007, p. 78). A defining feature of professionals is their particular skills, values and statues, which give them control and power to regulate the content of their work (Freidson 1994). However, as put forward in the literature on street-level bureaucracy, discretion—understood as the assessment of particular cases within a rule-bound context—is at the heart of street-level bureaucrats’ (SLB’s) work, meaning that they have choices to make about how policies are delivered and implemented in practice (Lipsky, 1980/2010; Hupe, 2013; Evans, 2010, Dworkin, 1977). In other words, doctors fulfil a double role as expert of knowledge and as authority.

Years of research has demonstrated how different social mechanisms affect policy outcomes, when policy goals are ambiguous (Brodkin 2011, Maynard-Moody & Portillo, 2010). Other studies point to the fact that SLBs’ discretion is influenced by much more than a regulative and a professional framework such as social stereotypes, social distance, personal values and moral concerns (Møller, 2011; Maynard-Moody & Musheno, 2003; Harrits & Møller, 2014; Watkins-Hayes, 2011) and how doctors’ discretionary practices in medical encounters are also shaped by social background, ethnicity and gender (Bertakis, 2009; Sandhu, Adams, Singleton, Clark-Carter, & Kidd, 2009; van Ryn & Burke, 2000; Willems, De Maesschalck, Deveugele, Derese & De Maeseneer, 2005). However, despite the potential influence of these patient-factors on doctors’ discretion it remains unclear how discretion is influenced by their own background and lifestyle as we prefer to address it here.

The article adds to this knowledge about what sources of influence inform the discretion at the frontline level by examining how lifestyle varies among GPs, and how their own lifestyles are used in their discretionary practices. Based on the concept of lifestyle as something guided by taste and practice (Bourdieu, 1984, p. 173-175), we argue that GPs compare patients to their own lifestyle when they are asked to identify potential risky behaviors prior to any symptoms. To study the structuring factors of GPs’ discretionary practices, we examine how a specific government-funded preventive healthcare program Check Your Health Preventive Program (CHPP) is carried out and affect the real lives of citizens. More specifically, we identify GPs’ discretion in preventive contexts, and analyze whether—and if so how—they are associated with aspects of their “general” lifestyle.

Theoretical framework – the influence of lifestyle on GPs’ discretionary practices

The essence of frontline work is that it requires individuals to make decisions about other individuals. Lipsky (2010) notes that street-level bureaucrats “have discretion because the nature of service provision calls for human judgment that cannot be programmed and for which machines cannot substitute” (p. 161). Consequently, discretion is a fundamentally necessary and inevitable part of their daily practice. Furthermore, GPs may also direct attention inward so as to meet the professional standards for good service delivery, which they internalize as part of their medical education (Freidson, 1970/2007; Mik-Meyer, 2012). Freidson (1970/2007) treats professionalism as an ideal type that is composed of different interdependent characteristics, of which factors of education and professional ideology are of particular interest. Medical school is a structural cornerstone in implementing and sustaining professional ideology and for socializing GPs into being loyal and committed to the profession (Freidson, 2001, p. 96–101). This explicitly emphasizes that GPs’ discretionary training originate from an institutionalized professional understanding of how to understand health and respond to patients. Furthermore, as GPs, they have to take the Hippocratic Oath to uphold specific institutionalized ideals of the medical profession, which primarily emphasize the ethical ideals of patient equality and autonomy (Mik-Meyer, 2012).

This suggests that work tasks, and professional ideology and knowledge inform GPs’ discretion practices, meaning that GPs expectedly perceive and address patients’ risky lifestyle behavior in relatively similar ways. However, discretion might also make way for the GPs’ personal assessments of risky lifestyle behavior, which create a basis for their discretionary practices to be informed by the GPs’ own lifestyles. This expectation is also supported by the fact that preventive efforts towards patients are never based on observable symptoms, but on experience and intuition with whether a particular patient appears to be one with a future health issue. In other words, the logic of prevention goes beyond their medical training.

Since GPs’ discretion of patients’ need for lifestyle intervention (also) rests on their intuition about the future health status of patients, we expect their discretion in these matters to be less influenced by professional norms compared to their discretion about treatments. Because preventive healthcare is an area with no clear-cut guidelines for GPs to follow, we expect GPs’ discretion to be relatively extensive in such contexts, thereby, paving the way for variation in their reactions to risky lifestyle, and their approaches to healthcare prevention. In other words, central to GPs’ work tasks is their use of personal intuition in their discretion of non–symptom-driven concerns about patients’ way of living, which we think allows room for variation between how GPs practice their discretion of patients’ need for lifestyle intervention in GP–patient encounters.

To elaborate on why this might be at stake, we draw on Bourdieu’s (1984) explanation of how lifestyle preferences and habitual dispositions function as a classificatory scheme in the judgment of others (p. 466-468), which we argue is at stake in preventive healthcare contexts in the GP-patient encounter.

Central to Bourdieu’s understanding of society, is that it is composed of various fields, each with its own internal logics and dynamics, in which agents struggle to improve or maintain their position with regard to the particular types of capital at stake (Bourdieu, 1984, p. 114; Mik-Meyer & Villadsen, 2007; Sulkunen, 2009). Based on this dimension of social structure, we view the health field as a rather broad field that includes all social groups in the social space. However, we exclude a general analysis of class here. We instead focus on the GP profession as a social group that understands and approaches preventive healthcare in a certain way, that is, by struggling to make their definition of the term risky lifestyle become dominant in their meetings with patients. To understand how GPs exercise discretion of need for future healthcare in the health field, we suggest focusing on the concept of habitus as the social practice in which lifestyle and social status are transformed into identity and behavior (Bourdieu, 1984, p. 170-175). We follow Bourdieu’s argument that habitus becomes the center of judgment of others. Habitus structures and produces a person’s own lifestyle practices such as personal taste of food, accessories, aesthetics, norms, values, and moral perceptions of right and wrong, and thereby causing that what comes naturally to oneself is perceived as the standard of which others are measured. Moreover, it functions as a classificatory scheme and represents an important factor in expressing the symbolic boundaries between one’s own lifestyle and those of others (p. 246). In that connection, we expect that aspects of the GPs’ lifestyle, such as diet, tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and physical activity—which also represent the key areas in public health—to be of particular importance to their discretion of patients’ need for lifestyle intervention, and hence their health preventive approach. According to this line of reasoning, GPs’ potential distinctness in terms of lifestyle might direct how they perceive and address risky lifestyle in preventive contexts. Thus, GPs’ problematization of citizens’ lifestyles might differ based on their own lifestyle.

Empirical data and methods

The empirical data were generated through semi-structured interviews with 15 GPs. Employing this method made it possible to access their narratives concerning lifestyle preferences, their reasoning about risky lifestyle and preventive approaches. Even though interview data cannot validate actual practice it can reveal reasons and motivations behind actions. We therefore explore the GPs’ experiences of themselves, their lifestyle, and descriptions of how they act in GP-patient encounters

The interviewees were all part of the government-funded preventive healthcare program CHPP. CHPP is a five-year randomized controlled trial investigating the impact of preventive general health checks performed in a municipality setting and subsequent conversations between GPs and citizens regarding health issues. As part of CHPP, every citizen between 30 and 49 years (approximately 26,000 people) in the municipality is invited to a general health check.

In Denmark, the Regional Public Authorities (RPAs) plan and finance general practice (Pedersen, Andersen, & Søndergaard, 2012). The RPA thus wields a great deal of power over GPs—in terms of not only reimbursements but also “forced” engagement in non-core task-related activities. The RPA, which initiated and financed CHPP, asked all 60 GPs in the municipality to partake in the program. The GPs had to engage in conversations with citizens following their participation in CHPP. A health check includes the measurement of height, weight, waist, lung function, physical fitness, and blood pressure, and the collection of blood samples for cholesterol and diabetes testing. Furthermore, the citizens were asked to answer a questionnaire concerning their mental health, physical activity, tobacco use, and alcohol consumption. The GPs’ role was to inform citizens about the results of the health check and to provide guidance to those citizens with a so-called risky lifestyle. The preventive program defines risky lifestyle in accordance with the recommendations of the Danish Health and Medicines Authority (DHMA), on diet, tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and physical activity.

Semi-structured interviews were carried out based on an interview guide containing diverse themes, including health perceptions, approach to health prevention, GPs’ own health-seeking behavior, and everyday life practices in terms of preferences for food, spare time activities, residential area, TV and media. Only a selection of themes—primarily GPs’ health related lifestyle preferences, and their approaches to health prevention,—is covered in the analysis.

The selection of interviewees was based on the criteria for recruiting a diverse group of interviewees (different ages and gender), aiming at capturing as much variance on lifestyle as possible. However, in practice the study was based on a convenience sample of five female GPs and ten male, ranging in age from their thirties to their sixties. The interviews (with the exception of one conducted in the private home of a GP) took place in the general practice clinics of the GPs and ranged in duration from 50 minutes to more than 120 minutes.

The interview data underwent qualitative content analysis, which made it possible to describe the GPs’ lifestyles and approaches to prevention by interpreting the content of the GPs’ narratives through a systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes and patterns. The interviews were transcribed verbatim and systematically coded with QSR software through various phases. The coding initially consisted of open coding, followed by (mainly) theoretically deductive coding, in which we focused on capturing the GPs lifestyle preferences, and the content of their discretion.

The GPs are referred to by a combination of “GP” and a number (01–15) in this paper.

Analyses

Distinct lifestyle variation among the GPs

From a Bourdieusian perspective, GPs comprise a relatively homogeneous social group in some aspects—owing to similarities in their educational background, professional ideology, work tasks, terms of employment, income, and the like. Therefore, theoretically we would assume them to share very similar lifestyle and habitus (Bourdieu, 1984, p. 169-208). Following this perspective, our analyses reveal an unexpected and distinct variation between the GPs’ lifestyles. Despite the fact that they were asked the same questions about diet, tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and physical activity they used very different reasoning and categories to address the content. Based on with-in cases analyses of each interview concerning these subjects, we identify different types of lifestyles among the interviewed GPs. In the following, we present the dominant differences in GPs’ reasoning and use of categories for living a certain type of lifestyle.

Lifestyle preferences constrained of time

Six GPs (GP01, GP03, GP04, GP08, GP13, and GP14) preferred a lifestyle where health per se should not become the all-important factor of everyday life. When they were asked questions about their preferences for physical activity and food, these GPs advocated for a lifestyle that allowed both enjoyment and fairly healthy living. Some of the GPs felt guilty about not “exercising” as intensively as they should in accordance with physical activity recommendations, even though they did not prefer to engage in physical activity on such terms. They instead incorporated “exercise” into social aspects of everyday life (e.g., spending a day on the golf course, playing badminton, horseback riding, walking, running, and sailing with friends) and into activities carried out in everyday life (e.g., bicycling to work). Despite having a guilty conscience, their reasoning for exercising in moderate amounts and intensity primarily concerned what was possible timewise.

These GPs also shared several similarities with regard to their food preferences. For example, they favored eating so-called ordinary food, preferably consisting of vegetables and whole-grain products. They also emphasized that they were not “renouncers”. They neither renounced sweets nor systematically preferred organic food. They characterized their preferred food as “fairly healthy” and as not time-consuming to prepare. In their opinion, the focus should be on enjoying the meal as a social event and pleasure rather than on preparing and cooking the meal. Hence, cooking from scratch is not necessarily a criterion because eating preferences, according to this perspective, are concerned with much more than obtaining proper nutrition. One GP (GP04) commented, “I don’t bake, you see, I like fast and easy solutions, I don’t spend a lot of time on cooking… we often cook stews with lots of vegetables, that one can quickly mix together.” In terms of Bourdieu’s (1984) emphasis on lifestyle as an exercise people do by marking good versus bad taste (p. 56-57), we interpret these GPs as someone that does not use health as a dominant marker of lifestyle. They consume food, drinks and exercise as pragmatic users rather than as dedicated to a certain position. This makes them different from another group of GP’s as we describe below.

Lifestyle preferences concerning self-optimization

Five other GPs (GP02, GP05, GP06, GP10 and GP12) expressed that their physical activity preferences are not only a means to good health, but also a positive consequence. These GPs described themselves as preferring intense physical activity and practicing high-intensity individual sports, such as marathons, triathlons, running, and cycling. One GP (GP06) remarked, “Doing sport is less about the physical and more about the psychological effect: It helps you become completely relaxed. I try to run three times a week, and I also do marathons.”

They emphasized the importance of physical activity to mental well-being, pointing to a lifestyle in which physical activity is an indisputable basic condition of a good life. These GPs simply cannot do without physical activity; otherwise, signs of restlessness and feeling ill occur. Some were motivated to include sport as an essential part of everyday life because doing so provide them with the opportunities to engage in competition, self-improvement and self-optimization. These GPs viewed physical activity as “sport,” whereas the GPs described above used the word exercise. We interpret their word choices as an indication of the differences between these two groups’ lifestyle preferences in terms of the role physical activity plays in marking themselves as persons.

These five GPs also talked about eating proper food, 1 which they associated with consuming natural and nutritious food that is eaten in accordance with specific regularities. These GPs substantiated their food preferences by referring to recommendations of the DHMA, which they incorporated as lifestyle-guiding principles. They also expressed distaste for individuals who do not take “evidence-based advice” into account and admitted a lack of understanding of those who just “feel one’s way.” Instead, their preferred foods are made from scratch with “good ingredients,” which to them primarily means “pure” organic ingredients. Take-away food, processed food, white bread, and fatty foods are not considered “real” food; rather, these types of food are of “improper quality.” 2 Thus, their food preferences suggest a lifestyle in which cooking and food connoisseurship go hand in hand (requiring investments in time and money), as well as a self-image and a classification practice to mark a distance between those who eat improper food and those—including themselves—who eat proper food. Thus, their reasoning of their preferred lifestyle clearly reveals an inherent perspective of self-optimization and taking advantage of one’s potential, as well as benefitting from the surplus values of leading a lifestyle on such terms.

This suggests that lifestyle, in terms of food and exercise, is used in accordance with Bourdieu’s understanding of positioning. That is, as a way to create identity through marking a distance to distaste—in this case distinguishing a certain way of eating and being with your body. We do however; find another position in our material of GP’s that are neither being pragmatic nor dedicated, but rather existential about their food choices and ways of living as exhibited in the following.

Lifestyle preferences concerning”feeling one’s way”

We identified two GPs (GP09, GP15), whose lifestyle practices are driven by their determination to live healthfully owing to bodily transformations. They themselves have experienced chronic disease regimens and planned weight loss, which have worked as catalysts for new health-related lifestyle preferences, transforming their bodies from one condition to another. However, these GPs’ new lifestyle practices are not about complying with recommendations. Quite the contrary, they are about “feeling one’s way.” These GPs prefer to expose their bodies to various influences, such as eating vegetarian and switching from caffeinated coffee to decaffeinated, out of curiosity to see how the body reacts. Furthermore, this experimental lifestyle recurs and manifests itself in the GP’s interest in and practice of self-knowledge and therapy (and even sexual preferences, as one GP mentioned) as a part of the GP’s lifestyle preferences.

To GP15, her lifestyle preferences are deliberate attempts to increase longevity, with the consumption of health food, for now, as an example. This GP described herself as a person who is “not afraid of feeling my way,” and explained that she would incorporate any kind of alternative diet advices into her own lifestyle, if it seems meaningful to her. She has already incorporated a specific health food that she had accidentally learned about from a patient into her “latest scheme to get old” (GP15). This example interestingly shows how the expected asymmetrical power relationship between the GP and the patient can be turned upside down, meaning that the GP, who is expected to be the medical expert, received advice from the patient, instead of the other way around.

These GPs’ preferences of acting out an experimental and alternative lifestyle distinguish them from the abovementioned GPs, and exemplifies that they base their food choices on quite different sources of knowledge. We interpret the GPs’ relatively more experimental lifestyle preferences as a way for them to creating self-identity, and manifesting open-mindedness as an important marker of lifestyle, positioning themselves in opposition to others who strictly adhere to evidence-based knowledge.

Lifestyle preferences resisting health authorities

Another two GPs (GP07, GP11) were different from the rest, because they insisted on maintaining their preferred lifestyle, regardless of whether or not it adheres to actual norms. Similar to the GPs who preferred practicing “sport”, GP11 also practices “sport” and uses to some extent the recommendations of the DHMA as guiding principles in his everyday life. Although GP11 is aware of the DHMA’s recommendations, he does not consider his weekly alcohol consumption of 35 units to be unhealthy. He believes that the recommendations are not applicable in his case because he has tested the effects of alcohol on his body and found these effects to be non-damaging. The GP (GP11) described his situation as follows:

I don’t believe that it’s unhealthy for me…. Once in a while I check—well, can it be measured anyhow? Nah. But then I try not to drink, being teetotal for a month a time. Does it make any difference in how I feel and to my physical condition? Do I feel it? Nah. I draw blood for testing and check my blood pressure, and I can feel what I’m capable of conditioning-wise and there’s absolutely no difference. Not in the slightest!

His description suggests that he is living a relatively more autonomous lifestyle, in which exceeding the alcohol consumption recommendations issued by DHMA is legitimized by arguments with a more biological basis.

In a similar way, GP07 explained that he has been smoking all his life. Even though he experiences an increased societal pressure to quit smoking, GP07 has resisted quitting. He commented, “I’m not stupid or unintelligent. I know smoking damages health, but smoking helps me feel well balanced”. These two GPs’ reasoning for living a certain lifestyle, thus suggests an emphasis on one’s individual right to live a certain lifestyle, even if it conflicts with public health recommendations.

According to Bourdieu’s’ analysis of upper class behavior and preferences well-resourced people mark their turf against others by turning what other people experience as collective (health) norms they cannot escape into a desire, or at least into something they actively choose to prioritize to do, or not to do. These GP’s way of experimenting with health are also a way of proving that they do not need to adhere to the same food, alcohol and exercise norms as others do, thereby marking themselves as different and superior to “ordinary people.”

Lifestyle preferences—constraints of structure and agency

Our analyses show that even though “healthy living” was highly valued among the GPs, and health-related practices occupied great parts of their everyday lives, their lifestyle preferences distinguished them from one another. Especially, the GPs’ reasoning for living a certain lifestyle distinguished them in terms of whether they tend to stress individual or structural constraints for acting, or not acting out their (risky) lifestyle preferences. References to time as an inadequate resource, which can be prioritized and economized dominated GP01, GP03, GP04, GP08, GP13, GP14’s reasoning about their lifestyle. We find that their emphasis on structural constraints, such as resources of time and energy, are perceived as conditioning for one’s opportunity to lead a certain lifestyle. Even though the remaining GPs’ (GP02, GP05, GP06, GP07, GP09, GP10, GP11, GP12, GP15) lifestyles vary in terms of contents, to a greater or lesser extent, their reasoning about their lifestyle preferences is discursively constructed based on agency perspectives. This suggests that these GPs, contrarily to the first group of GPs, stress individual agency in terms of leading a lifestyle by choice and one’s own responsibility, regardless whether it facilitates self-optimization, “feeling one’s way,” or legitimizes so-called vices. Moreover, the GPs’ preferences for lifestyle also varied, as manifested in different symbolic boundaries and classification practices of other people, practicing lifestyle different from them (Bourdieu, 1984, p. 466-467). Therefore, the question remains, whether and if so how the GPs’ distinctness in terms of lifestyle and their reasoning hereof has implications for their preventive approaches in patient-encounters.

Preventive approaches

The 15 GPs shared the view that interfering in matters related to patients’ lifestyle is detrimental to the GP–patient relationship. They also shared an understanding of themselves as “coordinators,” whom “patients can address whenever they have health concerns.” Relationships between GPs and patients rely on mutual trust and continuity; hence, to achieve success, the GPs stressed the importance of “not being judgmental.” However, the GPs expressed differing opinions on when this line should be drawn and whose lifestyles require intervention. Overall, we identify two main preventive approaches among the GPs, in which the distinction between viewing (patients’) lifestyle as contingent on agency or structures recurs.

Preventive approaches based on agency perspectives

Five GPs primarily described their preventive approaches based on individual agency. However, they varied in describing how individual agency was supposed to be put in play by themselves and their patients to facilitate non-risky lifestyles. Therefore, even though these GPs’ preventive approaches were characterized by individual agency the contents interestingly contained great diversity, and the GPs’ thus differently emphasized their own and their patients’ agency in terms of improving patients’ risky lifestyle, or improving patients’ ability to choose and adhere to their own definition of a reasonable lifestyle. As we demonstrate later, the agency perspective stands in contrast to another group of GPs’, who use structural constraints in their preventive approach.

Three GPs (GP02, GP05 and GP10) practice health prevention closely to the DHMA’s definitions of risky lifestyle, and associate lifestyle as deriving from the individuals’ free choice. These GPs state that they take a relatively more paternalistic approach to preventive healthcare and emphasize the importance of always trying to improve patients’ lifestyle. Furthermore, their attitude toward patient care is described as in opposition to that of “less dedicated GPs” who hold an “I can’t change anything anyhow attitude” (GP05). Thereby, emphasizing that a good GP keeps encouraging patients to live life the so-called right way even when patients are not always receptive to encouragement.

Quite the contrary, GP07 comment that he does not perceive health prevention to be a core output in general practice and that he does not promote preventive healthcare, unless patients actively seek it. He argues as follows:

You see, I’m educated to diagnose and treat. When people consult me, my job is to find out whether they’re sick or not…. I don’t want to fob off sickness on a man who feels he has a damn good life. I don’t want to act as the extended arm of the state and be involving in standardizing people…. That’s not my job…. I’m not good at telling people that they can’t drink, eat too much, or should keep a regular bedtime…. Because if these things don’t fit [in with] the patient [’s lifestyle], then they’ll never be healthy. And that’s a shame; it could be that they feel healthy on another way. (GP07)

As evident from GP07’s explanation, he is critical of the state’s dominant preventive healthcare agenda, which does not allow for subjective standards for “quality of life.” This GPs preventive approach thus stand in contrast to the DHMAs’ definition of risky lifestyle. Instead, he emphasizes the individuals’ right to resist societal pressure to lead a certain lifestyle.

Similar to GP07, GP09 primarily adopt his own layperson’s perspective, when discussing his preventive healthcare approach. He frequently mentions “anxiety” as a societal tendency to account for patients’ health-seeking behavior. Therefore, to deal with the core problem of anxiety, he applies a relatively more therapeutic discourse on health prevention, and deliberately focuses on patients’ self-development.

Preventive approach based on structural perspectives

The majority of the GPs (10 GPs) primarily talked about their preventive healthcare approach in a relatively more reluctant way. They also stress the importance of not viewing non-risky lifestyle as life’s only asset. These GPs apply a resource-based approach to preventive healthcare and underline how a non-risky lifestyle is not something that everyone can access and how individuals should not be held responsible for failing to achieve it. They also talked about patients’ health resources in terms of accumulated capital (Bourdieu, 1984, p. 291) such as energy, time, money, occupation, and educational level. Because they viewed living a healthy lifestyle as being contingent on resources, they did not problematize patients’ (different) lifestyles as an end in itself. One GP made the following comment:

Well, you can say I’ve got sympathy for those who’re in a bad position. Everything isn’t one’s own making. No, a lot of those who are in a bad position are so because their living conditions have been such from the start. (GP13)

Thus, the adoption of a resource-based preventive approach by GPs does not entail enforcing patients’ strict adherence to particular ways of living.

Above, we have shown the two main preventive approaches, in which the dominant distinction manifests itself in whether the GPs emphasize individual agency—and see themselves or their patients as able to influence their risky lifestyle—or whether they tend to stress structural constraints—such as resources and living conditions, impacting both GPs’ and patients’ ability to influence (risky) lifestyle. We found a similar distinction between the GPs’ reasoning for leading a certain lifestyle themselves. In the following we further examine the GPs ‘preventive approaches and study whether their discretionary practices are informed by their own lifestyle preferences and reasoning about risky lifestyle. If GPs’ habitual dispositions are reflected in their discretionary practices, this might cause quite different outcomes of GP-patient encounters.

Linking lifestyle and preventive approach

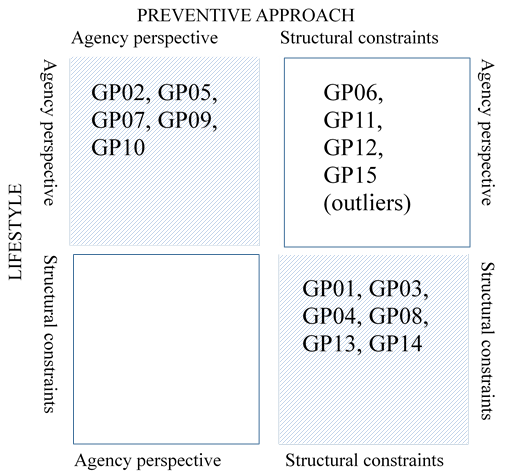

Figure 1 illustrates the identified patterns of correspondence between the GPs’ lifestyle preferences and their preventive approaches, in terms of whether their

reasoning is primarily based on agency perspectives or structural constraints.

As theoretically expected, in most cases (11) the GPs’ reasoning about their own lifestyle is reflected in their preventive approach. As seen in Figure 1, five GPs (GP02, GP05, GP07, GP09 and GP10) primarily explain their lifestyle preferences and preventive approaches based on agency perspectives, while six GPs (GP01, GP03, GP04, GP08, GP13 and GP14) stress structural constraints. Four GPs (GP06, GP11, GP12 and GP15) are placed as outliers because their reasoning about their own lifestyle does not converge with their preventive approaches. Interestingly, their preventive approaches are based on concerns about structural constraints, even though their own lifestyle preferences are explained through agency perspectives. We now delve into these patterns.

Agency perspectives explaining lifestyle and preventive approach

Three GPs (GP02, GP05 and GP10) explained their own preferred lifestyle and their preventive approach based on agency perspectives. These GPs often referred to their patients’ lack of knowledge of better health (contrary to themselves). One GP commented that patients could attain better health by simply letting go of “the perception that one is just unlucky in life and isn’t responsible for one’s own well-being” (GP02). These patients are considered passive partakers in their own lives and without the ability to master proper health management. That is, habitual dispositions differing from health recommendations are interpreted as misunderstood health behavior rather than as deliberate preferences. GP02 continues and compares these patients’ preferred lifestyles with his own, saying: “Some people think they are doing something good for themselves when eating chips in front of the TV. I like to say that I do something good to myself when I a go out for a run!” Inactive behavior (which is the opposite of his own) calls for paternalistic intervention, in which GP02 knowingly jeopardizes the patient–trust relationship in an effort to improve patients’ health behavior. He admits intervening in patients’ lifestyles, stating:

It can be a little transgressive to patients if I, strictly speaking, start talking about them being too fat, and they originally came because their big toe hurts…. They might feel offended, and I might not achieve what I wanted, but anyhow, I think I plant a seed. (GP02)

The GPs’ emphasis on pursuing both healthy living and a good life is thus imposed on patients. When describing their patients’ ability to master proper health management, these GPs used binary oppositions (e.g., active versus passive behavior, right versus wrong behavior, responsible versus irresponsible behavior) to distinguish patients. Their responses also suggest that a higher level of education and healthy living go hand in hand. Consequently, “highly educated” (as opposed to less educated) patients rarely need lifestyle intervention. These rough and stereotypical categorizations are understood as expressions of social distance and as distaste for citizens whose lifestyles are quite different from the definitions of appropriate (and healthy) lifestyle put forward by the GPs.

GP07 also kept emphasizing an agency perspective, in terms of his own and his patients’ right to live a so-called “risky” lifestyle without being stigmatized. He thus stresses the importance of resisting the standardization of health knowledge because its transferability to individual patients’ lives is not meaningful. He also emphasizes his own role as a “protector” of patients’ right to live health resistant, regardless of their health status, in terms of quality of life. In his own case, he says smoking gives him a sense of well-being and quality of life. According to GP07, constant reminders from the “patriarchal society” about how to live life the so-called right way and the lacking acceptance of so-called deviating lifestyles in a patriarchal society only create a sense of inferiority, doing more harm than good.

In a similar way GP09 advocates that one should disregard recommendations and instead “feel one’s way”—exactly how he reasoned about his own lifestyle. When describing his own lifestyle, GP09 clarified that his work in general practice “almost falls into the category of hobbies,” meaning that he is aware that his own lifestyle shapes his approach in general practice. GP09 notes that he never actively interferes in lifestyle matters, because he believes interfering in matters concerning patients’ lifestyle is equivalent to “exposing patients’ weaknesses”, which can destroy relationships built on mutual trust. Thus, this GP emphasizes that maintaining a good continuous GP-patient relationship is important and only possible if the GP does not appoint oneself the arbiter of right and wrong lifestyle behavior.

Structural constraints on lifestyle and preventive approach

The majority (6) of the GPs emphasize structural constraints for their own and their patients’ lifestyles, which does not entail enforcing patients’ strict adherence to particular ways of living. When bringing up issues related to patients’ lifestyle, GPs must strike a balance between addressing lifestyle issues and maintaining trust in the GP–patient relationship. Some GPs have developed a particular way of approaching lifestyle issues with their patients and maintain the trust relationship. GP14 describes how she deliberately chooses her words when assessing patients’ lifestyles as problematic:

I try not to be too finger-wagging. I kind of try to take their weight away from them and say: “Your body has grown bigger than what’s good for you.” Make it something external—something they cannot really help something that is seen as different from their personality.

The framing of lifestyle as something external emphasizes the fact that they understand the individuals’ agency as contingent on resources rather than morality or free choice. This view converge with the GPs’ own lifestyle preferences, in which resources are also experienced as constraining for one’s choices. In addition, some of them treat resource-disadvantaged patients differently from resource-advantaged patients so as to ensure that they are properly taken care of. One GP explains how she uses her discretion to ensure that all patients in need of a psychologist are provided access to one even if it means using rules “in a somewhat creative way” (GP14). This comment indicates that in certain situations, GPs are torn between a professional role as a doctor and an administrative role as a gatekeeper.

“Outliers”

As seen in Figure 1 four GPs are described as outliers. Contrary to the GPs described above, either primarily emphasizing individual agency or structural constraints when reasoning both about their own lifestyle preferences and their preventive approaches—these GPs’ own lifestyles do not seem to inform their discretionary practices. Therefore, these GPs are placed as outliers, because their reasoning about their lifestyle and preventive approaches, contrarily to our theoretically expectations, do not converge.

An interesting case is GP11, whose preventive approach is based on a structural perspective, emphasizing patients’ resources, even though his own lifestyle preferences involve an excessive consumption of alcohol.

Furthermore, both GP06 and GP12 are themselves very competitive in their approach to sport, and stress their lifestyle preferences concerning self-optimizing, and benefitting of the surplus values of such a lifestyle. However, their focus on individual agency is not reflected in their preventive approaches. Quite the contrary, describing their preventive approaches they stress inequalities in resources in terms of, time, money and education, and only touch upon prevention if the patient broaches it. Thus, these GPs are surprisingly tolerant towards so-called risky lifestyle and lifestyles differing from their own, supporting the need for further analyses of those GPs who resist being influenced by their personal understanding and values in their discretionary practices.

Concluding discussion

We have argued that GPs’ discretionary practices in healthcare preventive contexts are influenced by much more than a regulative and a professional context. As the analyses have shown, the lifestyles and preventive healthcare approaches of GPs vary. We identified different approaches to preventive healthcare, and different lifestyles among the interviewed GPs, with patterns of correspondence being present in most cases. The dominant distinction between both the GPs’ lifestyles and their preventive approaches manifests itself in whether they emphasize individual agency or structural perspectives as facilitating or constraining factors for leading a certain lifestyle, and intervening in patients’ (risky) lifestyles. Overall, this might, as also expected, explain some of the variation in the GPs’ discretionary practices, because the GPs use the same classificatory scheme in both their spare time and work life. Instead of exercising professional discretion in the same manner, the GPs’ tend to exercise professional discretion informed by their own lifestyle preferences, including personal judgment, commonsense perceptions, and subjective and diverse standards of knowledge. That is, GPs discursively construct their discretion of patients in need of lifestyle intervention by means of the very same distinctive preferences and values that form the basis of their own lifestyle (Bourdieu, 1984 p.173-175,466-468). We interpret this as evidence of autonomy in general practice where GPs act relatively autonomously, and differ in their reaction to preventive policies and in their discretionary practices.

However, the patterns of correspondence do not reflect a one-to-one ratio (see Figure 1), demonstrating that in certain cases (outliers) the GPs’ own lifestyles are not used in their discretionary practices. Thus there are indications as to other factors being important, supporting the need for further studies, in particular, of the mechanism causing resistance to let personal understanding and values influence discretion. These GPs were similar in their determination to prevent their own lifestyle from guiding their discretion, which speaks to the arguments put forward in both professional sociology (Freidson, 1970/2007) and street-level bureaucracy that the structural dimensions of education and task organization have a converging impact on discretion. However, this might also be a token of cross-pressure, in which GPs yield to patients demands, or simply let their lay-knowledge on structural constraints guide their preventive approach.

In addition, the presence of social distance was interestingly touched upon by some of the GPs who primarily based their discretionary practices on an agency perspective, which was reflected in their paternalistic preventive approach. These GPs’ characterizations of less educated patients as unsuccessful health managers and of highly educated patients as successful health managers support the need for further studies on the impact of social distance on patient assessments. If GPs assess patients differently based on stereotypes because of the social distance between them, they may also problematize socially positioned individuals (whom they may also categorize as patients) differently and their need for lifestyle intervention. Further research is thus warranted in which the focus is shifted from individuals who are defined as problematic to the social mechanisms surrounding the GP–patient encounter so as to understand the process of how GPs make the discretion that patients’ health behavior is problematic. Furthermore, our study does not say anything about GPs’ actual discretionary practices, pointing towards the relevance of further exploration on GP-patient encounters, including patients’ experiences so as to shed light on patients’ demands and their expectations to GPs’ handling of preventive consultations. Even though no empirical generalizations can be made, our analysis support findings from earlier studies on SLBs’ discretionary practices, suggesting that other sources than formal rules inform the discretion at the frontline (Dubois, 2010; Møller, 2011; Maynard-Moody & Musheno, 2003; Harrits & Møller, 2014; Watkins-Hayes, 2011). Furthermore, GPs comprise a case of a professional social group (Freidson, 1970/2007)—the medical profession—meaning that if their discretionary practices are influenced by their own lifestyle, we think it is reasonable to assume that this might also be the case of other in other professional social groups, such as among pedagogues and teachers, who are also in close contact with citizens and with the task of implementing preventive policies.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers as well as Vibeke Lehmann Nielsen, Gitte Sommer Harrits, Lars Thorup Larsen, Evelyn Brodkin and Søren Peter Olesen for their comments in the article’s early stages. Furthermore, we would like to thank the 15 general practitioners for participating as informants. Thanks for funding to Aarhus University, Folkesundhed i Midten, and Danish Society of General Practice.

Notes

References

- Bertakis, K. D. (2009). The influence of gender on the doctor–patient interaction. Patient education and counseling, 76(3), 356-360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.022

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste.

- Brodkin, E. Z. (2011). Putting street-level organizations first: New directions for research. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 21(2), i199-i201. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muq094

- Dworkin, R. M., & , . (1977). Is law a system of rules? In R. M. Dworkin (Ed.), The philosophy of law (pp. 38-65). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Oxford: Polity Press.

- Evans, T. (2010). Professional discretion in welfare service. Beyond street-level bureaucracy. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Freidson, E. (1994). Professionalism reborn: Theory, prophecy and policy. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Freidson, E. (2001). Professionalism, the third logic: On the practice of knowledge. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Freidson, E. (2007). Professional dominance: The social structure of medical care.

- Dubois, V. (2010). The bureaucrat and the poor: Encounters in french welfare offices. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Hupe, P. (2013). Dimensions of discretion: Specifying the object of street-level bureaucracy research. der moderne staat–Zeitschrift für Public Policy, Recht und Management, 6(2), 425-440.

- Harrits, G. S., & Møller, M. Ø. (2014). Prevention at the front line: How home nurses, pedagogues, and teachers transform public worry into decisions on special efforts. Public Management Review, 16(4), 447-480. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.841980

- Lipsky, M. (2010). Street-level democracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services.

- Lupton, D. (1995). The imperative of health: Public health and the regulated body. London: Sage Publications.

- Maynard-Moody, S., & Musheno, M. C. (2003). Cops, teachers, counselors: Stories from the front lines of public service. Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Maynard-Moody, S., & Portillo, S. (2010). Street-level bureaucracy theory. In R. Durant (Ed.), Oxford Handbook of American Bureaucracy (pp. 252-277). Oxford: University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199238958.003.0011

- Mik-Meyer, N. (2012). Den forstående læge og den evidenssøgende socialrådgiver: Rollebytte i hverdagens velfærdsstat. [The understanding doctor and the evidence seeking social worker: Changing roles in today’s welfare state]. In M. Järvinen & N. Mik-Meyer (Eds.), At skabe en professionel. Ansvar og autonomi i velfærdsstaten (pp. 52-75). Copenhagen, Denmark: Hans Reitzels Forlag. Creating a professional. Responsibility and autonomy in the welfare state.

- Mik-Meyer, N., & Villadsen, K. (2007). Bourdieu: Felt, symbolsk vold og underkastelse. [Bourdieu: Field, symbolic violence and submission]. In N. Mik-Meyer & K. Villadsen (Eds.), Magtens former. Sociologiske perspektiver på statens møde med borgeren (pp. 68-91). Denmark: Hans Reitzels Forlag Publisher. Shapes of power. Sociological perspectives on the encounter of the state with its citizen.

- Møller, M. Ø. (2011). Stereotyped perceptions of chronic pain. Tidsskrift for Forskning i Sygdom og Samfund, 7(13), 33-68.

- Pedersen, K. M., Andersen, J. S., & Søndergaard, J. (2012). General practice and primary health care in Denmark. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 25(Suppl. 1), S34-S38. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2012.02.110216

- Regeringen. (2014). Sundere liv for alle: nationale mål for danskernes sundhed de næste 10 år [A healthier life for everyone: national goals on danish health for the next 10 years]. Copenhagen, Denmark: Sundheds- og ældreministeriet.

- Sandhu, H., Adams, A., Singleton, L., Clark-Carter, D., & Kidd, J. (2009). The impact of gender dyads on doctor–patient communication: a systematic review. Patient education and counseling, 76(3), 348-355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.010

- Sulkunen, P. (2009). Disturbing concepts: from action theory to a generative concept of agency. In M. Leone (Ed.), Actants, actors, agents. The meaning of action and the action of meaning—from theories to territories (pp. 95-117). Roma: Aracne.

- Larsen, L. T. (2011). The leap of faith from disease treatment to lifestyle prevention: The genealogy of a policy idea. Journal of health politics, policy and law, 37(2), 227-252. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-1538611

- Vallgårda, S. (2001). Governing people's lives: Strategies for improving the health of the nations in England, Denmark, Norway and Sweden. European Journal of Public Health, 11(4), 386-392. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/11.4.386

- Van Ryn, M., & Burke, J. (2000). The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians' perceptions of patients. Social Science & Medicine, 50(6), 813-828. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00338-X

- Watkins-Hayes, C. (2011). Race, respect, and red tape: Inside the black box of racially representative bureaucracies. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 21(suppl 2), i233-i251. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muq096

- Willems, S., De Maesschalck, S., Deveugele, M., Derese, A., & De Maeseneer, J. (2005). Socio-economic status of the patient and doctor–patient communication: does it make a difference? Patient education and counseling, 56(2), 139-146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2004.02.011

- Zalmanovitch, Y., & Cohen, N. (2015). The pursuit of political will: Politicians' motivation and health promotion. The International Journal of Health Planning amd Management, 30(1), 31-44. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2203