Devin Rexvid and Lars Evertsson

Non-problematic Situations in Social Workers’ and GPs’ Practice

Abstract: This study aims to describe and analyze written accounts of non-problematic situations by 28 social workers and 24 general practitioners (GPs). The results show that non-problematic situations were connected to professionals’ control of the intervention process. Non-problematic situations were described by social workers as situations where they had control of the relationship with the client either by the use of coercive means or by the client’s active cooperation. GPs referred to non-problematic situations as situations where they had control of the intervention process mainly by the use of professional knowledge. One main conclusion is that the ability to control the intervention process through control of the relationship with the client may be of significance to those professions where a central part of the professional jurisdiction involves changing clients’ behaviors. This conclusion means that professional knowledge is not the only way to control the professional intervention process.

Keywords: Non-problematic situations; social workers; general practitioners; professional knowledge; intervention process; jurisdiction; tasks; technologies

In research on professions, non-problematic situation has received little attention. By non-problematic situations we mean situations where professionals perceive that their professional practice runs smoothly and without any rupture or breakdown. In this article, we will take a closer look at social workers’ and general practitioners’ (GPs) perception of non-problematic situations.

The literature on professionals in human service organizations tends to emphasize that a central aspect of professional work is to deal with uncertainty (Hasenfeld, 1983; Molander & Terum, 2010). This uncertainty is to a considerable extent related to the fact that clients, as thinking, feeling, and acting subjects, are unpredictable (Hasenfeld, 1983). Clients can neutralize and undermine the professional intervention process by acting in a non-compliant way (Aaker, Knudsen, Wynn, & Lund, 2001). By showing resistance or reluctance towards interventions suggested by professionals (Bremberg, Nilstun, Kovaca, & Zwittera, 2003; Calder, 2008) clients can rupture professional practice. Therefore, in human service organizations, client compliance is closely related to professionals’ ability to carry out their everyday professional practice (Hasenfeld, 1983; Lipsky, 2010).

In a previous article on social workers and general practitioners, we showed that the perceptions of problematic situations were connected to the disruption, lack of continuity, and loss of control of the intervention process (Rexvid, Evertsson, Forssén, & Nygren, 2014). These disruptions occurred in situations where clients were perceived to be reluctant, distrustful towards the professionals and unable to articulate their problems or comply with the proposed treatment (Rexvid et al., 2014). However, in the same study, we also collected data from social workers and general practitioners on their perceptions of non-problematic situations which we present and analyze in this article.

In this article, we study how social workers and GPs perceive non-problematic situations and how these situations relate to control of the intervention process comprised of the recruitment of clients, diagnosis, treatment, and termination of the case (Abbott, 1988; Hasenfeld, 1983). The aim is to describe and analyze social workers and GPs’ perceptions of situations in their practice that they have experienced as non-problematic. The specific research questions are:

-

What situations are experienced by social workers and GPs as non-problematic?

-

How can the differences between social workers and GPs’ perceptions of non-problematic situations be analyzed theoretically?

Literature review

The question of what constitutes non-problematic situations has received scarce attention. Previous research does not give a clear picture of what makes a situation non-problematic. In the literature that touches the area of “non-problematic situations,” the emphasis is on “easy cases” (Dunér & Nordström, 2005; Socialstyrelsen, 2004) or “simple problems” (Blom, Morén, & Perlinski, 2011; Glouberman & Zimmerman, 2002). Easy cases are contrasted with complex and “revolving-door cases” that is, cases that due to frequent occurrence cannot be closed (Dunér & Nordström, 2005). More specifically easy cases refer to cases where the client, his/her relatives, and professionals are generally in agreement about what support the clients need and how it should be worked out (Dunér & Nordström, 2005). Characteristic of easy cases also, according to Dunér and Nordström, is that professionals can handle them quickly and the execution of the intervention can be carried out quickly. Easy cases also refer to cases where the client’s need is clear-cut, the rules are clear, and the required support can be offered (Socialstyrelsen, 2004). The focus in the literature on easy cases tends to be on the relationship between clients and professionals.

Unlike easy cases, simple problems are contrasted to complicated and complex problems (see Blom, Morén, & Perlinski, 2011; Glouberman & Zimmerman, 2002). Simple problems are described as problems where “recipes,” that is, detailed instructions on how to solve a problem, are of central importance. Recipes are tested to ensure replication and produce standardized results. The characteristic of simple problems is that the best recipe gives good results every time (Blom et al., 2011; Glouberman & Zimmerman, 2002). In the discussion on simple problems, the main focus is on technical skills and less on how the relationship between the professionals and clients affects the experience of simple problems.

As we show in this section, the literature on non-problematic situations is not very rich. However, it provides some guidance on how to theoretically approach the phenomenon. The importance of technical skills and knowledge and a cooperative relationship makes it reasonable to assume that non-problematic situations mirror problematic situations in that it concerns the stability and continuity of the intervention process.

Theoretical framework

Based on the literature review we argue that social workers’ and GPs’ descriptions of non-problematic situations reflect situations where the professionals experience that they have control of the intervention process, that is, situations where the professional work does not break down but continues without serious disruptions. For professionals in human service organizations, this control may have both a knowledge dimension (Brante, 2014) and a relational dimension (Rexvid et al., 2014). The knowledge dimension, in a narrow sense, concerns the professionals’ knowledge of the client’s problems, or how to gain knowledge of the client’s problems and how to solve it (Brante, 2014). The relational dimension can include trust, distrust, truce, cooperation, and compliance (Rexvid et al., 2014). Both dimensions can be seen as indistinguishable parts of social workers and GPs’ practice. Our basic assumption is that knowledge is of fundamental importance for all professional work. However, depending on the two professions’ specific jurisdiction, the knowledge and relational dimensions of their practice can imply different impact on how they perceive the control of the intervention process in non-problematic situations.

Jurisdiction in this article refers to social workers and GPs’ publicly acknowledged right to through the use of professional knowledge perform certain tasks and monopolize certain domains of work (e.g., Abbott, 1988; Molander & Terum, 2010). Professional knowledge of social workers and GPs stands for both codified knowledge, obtained from education, scientific research, practice guidelines, legislation, and textbooks, and for personal knowledge comprised of codified knowledge in its personalized form as well as knowledge about procedures, processes, and knowledge based on experience (Eraut, 1994). Our basic assumption is that both professions use different types of knowledge to perform their tasks. However, in a Swedish study (Brante, Johnsson, Olofsson, & Svensson, 2015) of a number of professions, doctors highlighted scientific knowledge as the most important source of knowledge, then new research findings followed by everyday knowledge and knowledge of laws and legislation. In comparison, social workers emphasized knowledge of laws and legislation as the main knowledge source, followed by everyday knowledge, scientific knowledge, and finally new research findings (Brante et al., 2015). One way to understand this difference is that social workers as a profession with an extended right to exercise public authority in order to integrate and regulate clients is in need of knowledge of laws and legislation (see Brante et al., 2015; Levin, 2013). In comparison, the doctors’ highlighting of scientific knowledge as the main source of knowledge can be understood as an expression of the status of scientific knowledge as an ideal for doctors as a classic profession (Brante et al., 2015).

The jurisdictional tasks that social workers and GPs perform through the use of professional knowledge are human problems (see Abbott, 1988). The specific jurisdiction of these professions has a significant impact on the tasks that they are expected to perform and which clients they should serve (Hasenfeld, 1983). The jurisdiction of both professions has a moral character and includes tasks that involve the exercise of public authority because they are expected to be guardians of normality that is, normalize clients’ behavior or condition (Brante, 2014; Hasenfeld, 1983; Levin, 2013; SOU 2003:30, 2003; Svensson, 2015). Nevertheless, a considerable difference between the two professions is that many of the tasks that social workers carry out imply the exercise of public authority (Levin, 2013; Svensson, 2015). The social workers’ jurisdiction includes tasks that entail helping clients to change their behavior, either by active cooperation or by coercive measures (Levin, 2013). In comparison, the question of what tasks involve the exercise of public authority by GPs is not as clear as in the case of social work (see SOU 2003:30, 2003). GPs’ jurisdiction only in exceptional cases allows them to carry out tasks involving coercive intervention in the client’s life (SOU 2003:30, 2003; Svensson, 2015). To these exceptions belong the Communicable Diseases Act and Care under Compulsory Psychiatric Care Act (SOU 2003:30, 2003).

Social workers and GPs encounter a considerable degree of complexity in the enactment of their practice as the tasks they perform are to manage human problems (Hasenfeld, 1983). Although GPs’ jurisdiction means that they deal with medical problems as well as psychological problems, their work is often composed of management of physical problems, while the jurisdiction of social workers covers tasks involving management of social, economic, psychological, and behavioral problems. Social workers’ jurisdiction implies that they through the exercise of public authority in many cases change the clients’ behavior while GPs only in exceptional cases are allowed to take measures to change the clients’ behavior. Predicting and modifying human behavior, is according to Shanteau (1992) representing another kind of difficulty than predicting and resolving physical problems. This means that social workers in many situations can deal with another kind of complexity since their tasks more often than those of GPs involve not only an individual client but also several tentative clients from a whole family (see Mosesson, 2000) and modification of clients’ behaviour (Hasenfeld, 1983; Levin, 2013).

Moreover, both professions use different types of technologies in performing their tasks and to gain control of the intervention process (see Hasenfeld, 1983). Technologies stand for approaches and methods used by social workers and GPs to solve clients’ problems (see Hasenfled, 1983; Perrow, 2014). Generally, welfare professions employ different types of technologies, including Client attribute technologies, knowledge technologies, interaction technologies, client control technologies, and operation technologies (Hasenfeld, 1983). Which technology in which situation is used by social workers and GPs’ can be decided of the character of the tasks they perform that is, the stability versus instability and predictability versus unpredictability of the tasks (Shanteau, 1992). The task characteristics are according to Shanteau also essential for professionals’ control of the intervention process, even in cases where the professionals possess relevant knowledge. Social workers and GPs’ use of certain technologies does not only touch the knowledge dimension of the practice but also the relational dimension as the professionals’ relationship with the clients in many situations implies a decisive impact on which technologies should be employed.

Methodology

In this study, we conducted a qualitative content analysis of 52 written accounts of situations perceived as non-problematic by social workers within personal social services, and by GPs within primary health care clinics in Sweden (see Table 1). All of the social workers and GPs were employed by Swedish local government: the GPs by the county councils and the social workers by the municipalities. As shown in Table 1, the social workers in this study worked with child protection, monetary benefits, and addiction. These areas represent a large segment of social work in Sweden since the majority of social workers in Sweden are employed by municipalities and work within Personal Social Services. The professional practice of social work within these areas typically involves the exercise of public authority. However, it is worth mentioning that publicly employed social workers are present within other areas of the welfare state in Sweden.

Table 1

Sample overview

|

Social workers |

General practitioners |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Sex |

Female = 24, male = 4 |

Female = 12, male =12 |

|

Age |

Median = 37.5, youngest = 27, oldest = 66 |

Median = 50, youngest = 28, oldest = 66 |

|

Work experience |

Median = 6.5 years, max = 40 years, min = 2 years |

Median = 12 years, max = 35 years, min = 2 years |

|

Area of professional work |

Child protection: 16, monetary benefits: 8, addiction: 4 |

Primary health care |

Data collection

The data was collected between May 2011 and February 2012. The recruitment of social workers and GPs was carried out by email. Our aim was to capture a wide variety of experiences of non-problematic situations which was the reason why we only contacted social workers and GPs with at least two years’ work experience. The e-mail message was comprised of a brief presentation of the study, the ethical principles concerning confidentiality, voluntary participation, and informed consent. The email message also contained a questionnaire that covered the respondents’ professional background and instructions on how to report situations that they had perceived as non-problematic. The respondents were given the following instruction:

We ask you to give an example of a situation, or different types of situations, where you feel that your work with the client runs without problems. We want that you clearly address: 1) What makes the work non-problematic in such situations? and 2) If you have several options regarding the way of handling and selection of measures, how do you choose between them?

As the quotation shows, we did not provide the respondents with any definition of a non-problematic situation.

Our aim was to collect a relatively small body of data containing pregnant and credible accounts of non-problematic situations (see Patton, 2002). We sent an email to professionals in several municipalities and counties at different times and received 52 responses.

Analysis

The written accounts were analyzed by using a conventional content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Initially, the codes were derived from the data and defined during data analysis. More specifically, the conventional content analysis was aimed to provide a multifaceted understanding of non-problematic situations.

In the first stage of the analysis, the researchers separately read and coded the data. This first stage resulted in several codes covering different aspects of what made a certain situation to be perceived as “non-problematic.” The codes were the outcomes of a process where sentences and paragraphs in the accounts were condensed. This means that the codes were generated from a reading of the data with an open attitude (Alvesson & Kärreman, 2007). An open attitude does not mean that we avoided theory or postponed theory utilization; rather it included a broadening of our vocabulary and theoretical repertoire in order to consider more and less self-evident aspects of the professionals’ perceptions of non-problematic situations (Alvesson & Kärreman, 2007). The self-evident aspect was that non-problematic situations referred to situations where the professionals experienced that they had the intervention process under control. The codes from the first analytical step were rearranged into three analytical main categories that are used in the article and elaborated further in the next section.

In the discussion section, we analyze our findings within a theoretical framework of the sociology of professions and human service organizations. This will guide our analysis and deepen our understanding of what it is that makes certain situations to be perceived as “non-problematic.”

Results

As mentioned initially, non-problematic situations stood for situations where social workers and GPs were in control of the professional intervention process. In this section, we show that social workers perceived that they gained control of the intervention process through control of the relationship with the client. GPs, however, experienced that non-problematic situations were linked to the control of the intervention process through control of professional knowledge and knowledge utilization.

Social workers’ perceptions of non-problematic situations

Common to social workers’ descriptions of non-problematic situations was, as noted earlier, control of the relationship with the client. More specifically, for social workers non-problematic situations referred to situations where they perceived that they were dealing with clients who exhibited a competent behavior or misbehaved to such an extent that the social workers were left with no other option than to use statutory coercive means. In the following two sections, we begin with a description of non-problematic situations due to competent clients and end with depictions of non-problematic situations due to situations of “left with no choice.”

Non-problematic situations due to competent clients

Working with clients who respected social workers’ professional authority, took a positive stance towards suggested interventions and showed motivation, self-awareness, and a willingness to change, was central to social workers’ descriptions of non-problematic situations. The situations were experienced as non-problematic as these clients were perceived as behaving competently, rationally and did not challenge social workers’ control of the professional intervention process. According to the social workers, these competent clients typically lacked “real” social problems or only had minor social problems, which did not require interventions aiming at changing the clients’ conduct or lifestyle. Unaccompanied refugee children, as in the quotation below, were an example of clients who were described as being without real social problems and at the same time positive towards the work of social workers.

I think it is non-problematic to handle unaccompanied refugee children. Children who lack severe social problems and where my work is more about planning where they should stay and provide for their basic needs. What makes it non-problematic is that they are motivated to get help and support, and they rarely have negative prejudices towards social services. (SW18)

Clients with minor social problems involved those who, due to sudden and unforeseen life events, were in temporary need of help and support by social workers. These clients were often seen by social workers as victims of circumstances beyond their control, for example, in the case of sudden unemployment. Working with these clients was non-problematic since they were regarded as responsible and resourceful clients and made active efforts to become self-sustaining and stay out of trouble in the future.

I had a family that was both mentally and physically healthy; they had no addiction problems. They wanted to have monetary assistance in order to make ends meet during a period of temporary unemployment. They lived below the national norm for social assistance and wished to supplement their low income. They were economically competent and cooperated well with me throughout the whole process of finding work. I believed in what they said. They were trustworthy, and I could help them without any doubts. (SW 1 12)

But even some situations where clients had more complex social problems such as drug abuse or child abuse that called for interventions aiming at changing the clients’ problematic behavior or lifestyle were described as non-problematic if the clients showed a competent behavior by taking a responsible attitude and a willingness to change. In the example below, the situation is described as non-problematic, as the client, suspected of child abuse and deficient parenting skills, exhibited self-awareness and a willingness to change.

What makes it non-problematic is that the mother shows that she is capable of taking charge of her own life and the life of her children. She shows that she is capable of identifying and working with her problems in a promising manner. So the situation has gone from an increased need for control and intervention by the social services to a situation where we can let her decide how she wants to carry on with her life. (SW4)

Social workers also described situations in which they felt that they could rely on the clients’ own responsibility and trust during the intervention process as non-problematic.

Work with families where there is a sincere desire to change usually goes without problems.… The situation becomes non-problematic as the family decides what they want to change and how which often creates a greater commitment and greater probability of success than if the social workers decide what the problem is in the family.… If there is a collaborative alliance, it is also possible for the social worker to raise difficult questions that require trust and confidence in the social workers to manage. (SW15)

In this section, we have shown that central to social workers’ perception of the non-problematic situation was that clients granted social workers’ control of the intervention process, by expressing a cooperative attitude to the intervention process and by displaying competence by staying out of trouble or being motivated to change a problematic life-style.

Situations of “left with no choice” as non-problematic

Social workers’ perception of non-problematic situations was not limited to dealing with competent clients. Situations characterized by dealing with clients with complex social problems and a reluctance to cooperate and change were also perceived as non-problematic when the social workers were left with no other options than conducting coercive actions. Typically, this involved situations where clients’ behaviors posed a danger to themselves or others.

A non-problematic situation is, I think when you do not have any other options. For example, if a client is in such a bad condition that he or she must be admitted to hospital. Or if someone needs to be cared for under LVM [the Care of Substance Abusers Act] in order to survive. (SW6)

Through legal coercive actions, social workers gained control of the intervention process. The use of coercive actions left clients with no or little opportunity to protest or object to the intervention suggested by the social worker, hence leaving them in control of the intervention process.

General practitioners’ perceptions of non-problematic situations

Non-problematic situations due to competent GPs

Social workers’ accounts of non-problematic situations differed from the GPs’ accounts. Where social workers’ accounts of non-problematic situations referred to situations in which they gained control of the intervention process by control of the relationship with the client, GPs’ accounts mainly referred to situations where they gained control of the intervention process by access to and use of professional knowledge and their ability to act competently in accordance with that knowledge when handling the client’s problem. In their accounts, GPs’ referred to different forms of professional knowledge such as experience-based knowledge, evidence-based knowledge, pattern recognition, guidelines, and diagnostic codes.

Individual patients who only have a single medical problem—high blood pressure or a sprained foot. It is quick. It’s just listening to the patient and taking action based on evidence and my long professional experience. (GP 2 2)

The handling of well-defined ailments covered by evidence and diagnostic codes is non-problematic. These include the treatment of respiratory infections, hypertension, bowel investigations, hypothyroidism and many musculoskeletal problems. (GP6)

In the GPs’ accounts, knowledge codified in decision aids such as diagnostic manuals or different kinds of practice guidelines appeared to be an important resource to make an accurate diagnosis as a competent GP. Non-problematic situations were thus, as the following excerpt shows, perceived as situations where GPs experienced that they had access to relevant knowledge which made it possible to interpret the clients’ symptoms, what the symptoms represented, and the severity of the client’s medical condition.

Old man with a sore shoulder. Had received a cortisone injection a month ago, but the symptoms have returned now. Classic impingement. Non-problematic due to clear somatic complaints that were in accord with a clear diagnosis that leads right up to treatment; thus, simply a straightforward decision. (GP13)

Treatment of medical problems for which there are clearly formulated guidelines for medical intervention, for example, heart failure, dementia, hypertension, etc. (GP3)

Knowledge codified in diagnostic decision aids was also described as decisive for GPs’ choice of treatment, and decisions whether the client would be referred to more specialized care.

An obvious referral case—acute or non-acute— for example, referral to the eye clinic for cataract surgery, to the surgeon for an inguinal hernia, to the children’s clinic/pediatric clinic when a child has an RS virus, etc. It is non-problematic when it is easy to diagnose and when there is help available within a reasonable time. (GP7)

Moreover, situations were also experienced as non-problematic when GPs through access to relevant knowledge could easily make a diagnosis. This is because in such situations GPs were enabled to carry out their professional tasks effectively without wasting time or medical resources.

The patient is already diagnosed over the phone, and I just have to meet the patient briefly to confirm the diagnosis. It is time-saving for me and satisfying for both me and the patient. (GP5)

In the non-problematic situations above, access to different sorts of knowledge gave GPs control of the intervention process since access to relevant knowledge codified in decision aids and guidelines and the use of knowledge was linked to core professional activities such as interpreting symptoms, making a diagnosis, and choosing the right treatment for the client.

Summary

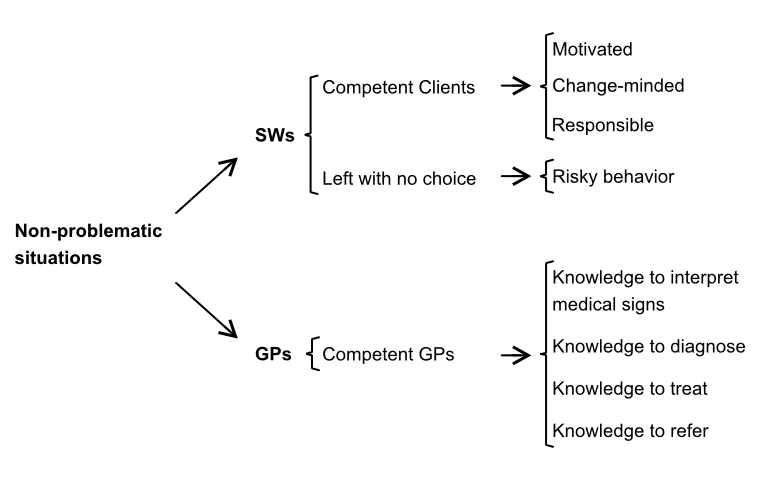

In the previous section, the first research question was addressed. We showed, as Figure 1 below summarizes that non-problematic situations were connected to being in control of the intervention process. The social workers perceived non-problematic situations as situations where they had control of the relationship with the client, either by the use of coercive means or by the client’s active cooperation. Dealing with situations where the clients posed a danger to themselves or others was described as non-problematic since it left social workers with no other choice than the use of coercive means to bring the intervention process under control. Dealing with clients taking a positive attitude towards the social worker’s suggested intervention was referred to as non-problematic since the social workers did not experience that they had to exercise public authority in order to have the intervention process under control. In comparison, GPs perceived that they gained control of the intervention process by the use of their professional knowledge. GPs described the use of professional knowledge as a key factor in bringing the intervention process under control since it was intimately linked to the interpretation of the client’s symptoms, and to the GPs’ ability to make a diagnosis and to choose a treatment.

It is interesting to notice that in their accounts of non-problematic situations the social workers did not refer to use of professional knowledge and the GPs did not make references to the importance of the relationship with clients. Does this mean that knowledge is of no importance to social workers in handling non-problematic situations, or that the relationship with the clients is unimportant to GPs? We do not believe it is, and in the next section, we will argue that this difference between social workers and GPs reflect differences related to the professions’ different jurisdiction, tasks, and relationship with the clients.

Discussion

In this section, the second research question is discussed: How can the differences between social workers’ and GPs’ perceptions of non-problematic situations be analyzed theoretically. The differences are analyzed within a framework that highlights: 1) social workers’ and GPs’ different jurisdiction, 2) how these differences in jurisdiction affect the professional tasks performed by social workers and GPs, and 3) the factors that condition these professions’ encounters with their clients (see Table 2).

Jurisdiction and tasks

As mentioned earlier, the major difference between the two professions, in this study, was that social workers’ perceived that non-problematic situations were intimately linked to the control of the relationship with the client. In comparison, GPs perceived that non-problematic situations were linked to access to and use of professional knowledge.

To understand how two welfare state professions can have such different perceptions of non-problematic situations, we first turn our attention to the jurisdiction that their professional practice rests on. Within welfare states like Sweden, the state is a central actor in shaping the jurisdiction of welfare professions (Evertsson, 2000). As these professions have close ties to the welfare state, it is not surprising to see certain similarities between them. One of these similarities is that the professional practice of social workers and GPs has a moral character (Hasenfeld, 1983). Another similarity is that both professions are exercising public authority in relation to their clients (Hasenfeld, 1983; Levin, 2013; SOU 2003:30, 2003). Despite these similarities, the jurisdiction of social workers and GPs differs in many respects. The two professions exercise public authority in different ways and to various extents in order to perform their professional tasks. One of the focal aspects of social work as a professional practice, especially relevant to social workers exercising public authority in personal social services, is the jurisdictional task to help clients to change or modify their behavior (Akademikerförbundet SSR, 2013; Hasenfeld, 1983; Levin, 2013; Svensson, 2015). The social workers’ jurisdiction ultimately rests on their right to make decisions and take action that in specific cases go against the will of the clients, ultimately by the exercise of coercive means (Levin, 2013). As mentioned earlier, the jurisdiction of GPs is also moral in its character. However, even though preventive medicine can be argued to have a moral character, the professional practice of GPs is generally more focused on changing the medical status of the patients than the patients’ way of life. Central to GPs’ jurisdictional tasks is to cure, relieve, and comfort on a voluntary basis (Akademikerförbundet SSR, 2013; Freidson, 1961). Only in exceptional cases, GPs in Sweden are allowed to perform tasks which involve coercive interventions in a client’s life. To these exceptions belong, for instance, the Communicable Diseases Act and Care under Compulsory Psychiatric Care Act (SOU 2003:30, 2003).

Given these differences in jurisdictional tasks, it could be argued that in non-problematic situations, it is of greater importance for social workers than GPs to control the relationship with the client in order to successfully fulfill their jurisdictional commitments (Biestek, 1957). For social workers exercising public authority to change or modify clients’ behavior or lifestyle is a daunting task that becomes even harder in situations where clients oppose or reject such change. Against this background, it is understandable that social workers in this study perceived situations where clients acted responsibly and cooperated or where they could use coercive means as non-problematic.

Professional technologies

The different character of the social workers and GPs’ jurisdiction and tasks is reflected in the professional technologies that the professions rely on. Following Hasenfeld’s (1983) typological concept of technology in his theory of human service organizations it could be argued that, given that one of the central tasks of professional social work involves changing or modifying clients’ problematic behavior or lifestyle, social workers heavily rely on interaction technologies and client control technologies. Social workers’ jurisdiction and professional tasks are thus based on the use of technologies in which the relationship to the client plays a central role. Once again, it is understandable why social workers in this study perceived situations where clients complied or could be brought under control as non-problematic.

Compared to social workers, the jurisdiction and professional tasks of GPs’ rest to a lesser extent on the exercise of public authority, which reduces the likelihood that the relationship between GPs and their clients becomes tension-filled in non-problematic situations (see Freidson, 1961; SOU 2003:30, 2003). It is reasonable to believe that clients of GPs more often seek help voluntarily than do clients of social workers, which means that in order to control the intervention process GPs in non-problematic situations do not need to make use of interaction and client control technologies as often as social workers (Freidson, 1961). In the forefront of GPs’ jurisdiction and professional tasks is the improvement of clients’ clinical (medical) status, rather than the modification of the clients’ conduct if not changes in clients’ lifestyle are medically motivated. In non-problematic situations, the performance of tasks which involve working with clients’ medical status is, therefore, more likely to be a matter of applying medical knowledge rather than controlling the relationship with the client.

Social workers’ and GPs’ encounters with clients

It is reasonable to believe that social workers and GPs’ different jurisdiction, tasks and use of technologies color their encounter with clients. Previous research shows that clients of social workers experience a lack of control of how and when to exit the relationship with social workers (Hasenfeld, 1983; Hirschman, 1970) and that many are involuntary in the sense that they only reluctantly seek help from social workers and do not wish to identify themselves with the social problems that social workers attribute to them, since many social problems are attached with shame and stigma, especially problems that the client is held accountable for (Hasenfeld, 1983; Levin, 2013; Smith et al., 2012). Claims from social workers to be the expert and holder of professional knowledge on the clients’ social problems are, therefore, often met with objection and distrust, and social workers constantly need to work actively to transform an institutionalized distrust into a trusting relationship with the client (Levin, 2013; Smith et al., 2012). Against this background, it is not surprising that social workers can perceive cooperating and trusting clients or situations in which they can take coercive action as non-problematic.

The difference between the two professions can be understood when we consider that many clients of GPs often come voluntarily to seek help for their health problems (Freidson, 1961). In comparison to many of the clients of social workers, they have greater control of their entry into and exit from the professional encounter (Freidson, 1961). The relationships between GPs and their clients in non-problematic situations tend to be based on trust and “truce” (Nelson & Winter, 1982), which means that the parties involved tend to try to downplay conflicts of interest and the power imbalance (Rexvid et al., 2014). Moreover, in non-problematic situations, it is also common that clients and GPs are often in accord that it is the GP who is the expert, holder of professional knowledge and who should have the privilege of defining the client’s problems (Freidson, 1961; Johnson, 1972). Furthermore, medical diagnoses are, unlike social problems, more often detached from shame and stigma, and clients of GPs are, with the exception of lifestyle problems, not usually held responsible for their medical problems. For GPs, the problem to be managed is often the client’s medical condition rather than the clients’ behavior (Freidson, 1961). Against this background, it is understandable that the GPs in our study perceived non-problematic situations to be a matter of utilization of professional knowledge rather than of controlling the relationship with the client.

To summarize, it is our understanding that the observed difference has something important to say about the conditions that shape the professional practice of social workers and GPs.

First, the emphasis social workers put on the relationship with the client reflects that professional social work practice or social workers’ professional tasks are to a considerable extent conditioned by the client and how the interaction between social workers and clients is played out. Seen from the perspective of professional social work practice, the relationship with the clients represents an element of uncertainty that needs to be managed (Jutel & Nettleton, 2011). The greater the uncertainty about the client’s openness to change, motivation and cooperation, the greater the social workers’ need to control the relationship with the client (Hasenfeld, 1983). Against this background, we argue that the relationship between social workers and their clients is at the heart of professional social work practice (Carla & Grant, 2009; Hasenfeld, 1983; Knei-Paz, 2009) and that control of the relationship with the client may constitute the single most important aspect of professional social work practice in non-problematic situations. It indicates that control of the relationship with the client is prior to and conditions social workers’ choice and use of professional knowledge and knowledge-based interventions. The professional practice of social workers and their tasks rest on different kinds of professional knowledge, but the possibility to use that knowledge is conditioned by having control of the relationship with the client in non-problematic situations. Put differently the professional social work practice rests on both social workers’ ability to control the relationship with the client and the use of professional knowledge. The same might be true of the professional practice of GPs, but we would argue, to a much lesser extent with regard to the relationship with clients. In comparison to the practice of social workers, it is the knowledge dimension of GPs’ professional practice and not the relational dimension that is stressed by GPs, since control of the relationship with the client is less likely to constitute a problem in non-problematic situations. Primarily they are applying professional knowledge to symptoms described by clients (Jutel & Nettleton, 2011). In non-problematic situations, professional knowledge is the key asset to control the intervention process (Jutel & Nettleton, 2011; Michailakis & Schirmer, 2010) as the clients do not tend to disrupt GPs’ professional practice by questioning their expertise (Rexvid et al., 2014). In such situations, GPs become aware that being in control of professional knowledge mean being in control of the intervention process.

Methodological and theoretical reflections

We believe that this study has something important to say about the different conditions that shape the professional practice of social workers and GPs. However, from a methodological perspective, it is important to consider that this study does not cover all areas of social workers’ and GPs’ practice. It is possible that our findings would have been somewhat different if we had studied areas of social work less characterized by the exercise of public authority such as preventive work or social support to the elderly and disabled. Therefore, when studying other areas of social and medical professional practice, our findings should only serve as a starting point for further investigation.

Although our aim has been to describe and analyze social workers’ and GPs’ perception of non-problematic situations, it is, given our findings and analysis, necessary to theoretically reflect on the concept of knowledge. We are aware that knowledge is a complex phenomenon that involves more than cognitive aspects. Furthermore, we recognize that social worker's ability to build and maintain supportive and meaningful relationships with involuntary or unmotivated clients can be considered as a matter of knowledge utilization. Despite this, we argue that it is sometimes important—as in this study—to make an analytical distinction between knowledge and relationship.

Our decision to make an analytical distinction between knowledge and relationship, as two different aspects of professional practice, is twofold. Our first reason is to remain close to our empirical data. In our empirical data GPs link problematic situations to knowledge, while social workers connect non-problematic situations to control of the relationship with the client. This means that the distinction between knowledge and relationship is present in on our empirical findings. We find it difficult to ignore this fact. The second reason is that the analytical distinction contributes to new knowledge by showing that there are different ways for professionals to gain control of the professional intervention process. For GPs professional knowledge seems to be a key tool to gain control of the intervention process while control over the relationship with clients seems to be of substantial importance for the social workers. Based on our findings we suggest that gaining control over the intervention process through establishing control of the relationship with the client represents another and different mode of professional control than the use of knowledge. Without an analytical distinction between knowledge and relationship, this insight would be lost.

Conclusions

In this study, we have shown that non-problematic situations were perceived as situations where the professionals experienced that they had control of the intervention process but in different ways. More specifically the findings indicated that the two professions put different emphasis on the knowledge dimension and relational dimension of their practice.

Our findings are both in accord with, and differ from previous research and theory, on professions. The results are consistent with previous research on professions by showing that professional knowledge is a key resource through which professions build jurisdiction and gain control over the intervention process (see Abbott, 1988; Brante et al., 2015). However, this study has also shown that there are more ways for professions to establish control over the professional intervention process. Following Hasenfeld (1983), we argue that control over the relationship with the client is essential to any profession that is engaged in changing or modifying clients’ moral conducts, problematic behaviors or lifestyles. In the article, we refer to this mode of control as the relational dimension of professional practice, and we understand client compliance to be a key mechanism (Hasenfeld, 1983) to this mode of control.

However, this does not necessarily imply that professional knowledge is of less importance to professions where a core jurisdictional task is changing or modifying clients’ moral conducts, problematic behaviors or lifestyles. A more reasonable interpretation is that, for some professions, such as social workers, the use of professional knowledge is conditioned by the relationship with the client. Professions that are more likely to work with unmotivated, involuntary and non-compliant clients might find that their possibility to work in accordance with established professional methods, standards, guidelines or routine are conditioned by the relationship with the client.

Seen from this perspective, our findings are thought-provoking. They raise the question whether “more” and “better” knowledge, as a key component in the Swedish state’s knowledge governance (Alm, 2015), is always the best way to go in order to improve professional practice. It also raises a question whether the strategy of enhancing professional practice through evidence-based knowledge and practices, guidelines and manuals, needs to be more sensitive towards different professions’ jurisdiction, that is, the character of their tasks, technologies and the character of their relationship with the client. Tension-filled relationships between professionals and clients can hamper the implementation of context-independent knowledge (Brante, 2014) and condition professionals’ ability to use that knowledge.

References

- Aaker, E., Knudsen, A., Wynn, R., & Lund, A. (2001). General practitioners’ reactions to non-compliant patients. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 19(2), 103-106. https://doi.org/10.1080/028134301750235330

- Abbott, A. (1988). The system of professions. An essay on the division of expert labor. London: The University of Chicago Press.

- Akademikerförbundet SSR. (2013). Etik i socialt arbete: etisk kod för socialarbetare [Ethic in social work: ethical codes for social workers]. Stockholm: Akademikerförbundet SSR.

- Alm, M. (2015). När kunskap ska styra.Om organisatoriska och professionella villkor för kunskapsstyrning inom missbruksvården, [When knowledge is the ruling force. On organizational and professional conditions for knowledge governance in substance abuse treatment] (Doctoral dissertation). University of Växjö, Växjö.

- Alvesson, M., & Kärreman, D. (2007). Empirical matters in theory development. Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1265-1281. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2007.26586822

- Biestek, F. P. (1957). The casework relationship. Chicago, Ill.: Loyola U.P.

- Blom, B., Morén, S., & Perlinski, M. (2011). Hur bör socialtjänstens IFO organiseras? [How personal social services ought to be organised?] Socionomen, 4, 12-16. http://umu.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A419713&dswid=9306

- Brante, T. (2014). Den professionella logiken: hur vetenskap och praktik förenas i det moderna kunskapssamhället (The professional logic: how science and practice unite in the modern knowledge society). Stockholm: Liber.

- Brante, T., Johnsson, E., Olofsson, G., & Svensson, L. G. (2015). Professionerna i kunskapssamhället: en jämförande studie av svenska professioner (The professions in knowledge society: a comparative study of Swedish professions). Stockholm: Liber.

- Bremberg, S., Nilstun, N., Kovaca, V., & Zwittera, M. (2003). GPs facing reluctant and demanding patients: analysing ethical justifications. Family Practice, 20(3), 254-61. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmg305

- Calder, M. C. (2008). The Carrot or the stick? Towards effective practice with involuntary clients in safeguarding children work. Lyme Regis: Russell House Publishing.

- Carla, A., & Grant, C. (2009). Caring, mutuality and reciprocity in social worker client relationships: Rethinking principles of practice. Journal of Social Work, 9(1), 5-22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017308098420

- Dunér, A., & Nordström, M. (2005). Biståndshandläggningens villkor och dilemma (The conditions and dilemmas of aid administrators). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Eraut, M. (1994). Developing professional knowledge and competence. London: Falmer Press.

- Evertsson, L. (2000). The Swedish welfare state and the emergence of female welfare state occupations. Gender, Work and Organization, 7(4), 230-241. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0432.00111

- Freidson, E. (1961). Patients’ views of medical practice. York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Glouberman, S., & Zimmerman, B. (2002). Complicated and complex systems: What would successful reform of Medicare look like?. http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.plexusinstitute.org/resource/collection/6528ED29-9907-4BC7-8D00-8DC907679FED/ComplicatedAndComplexSystems-ZimmermanReport_Medicare_reform.pdf

- Hasenfeld, Y. (1983). Human service organizations. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

- Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty: responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univiverstity Press.

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277-1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Johnson, T. J. (1972). Professions and power. London: Macmillan.

- Jutel, A., & Nettleton, S. (2011). Towards a sociology of diagnosis: Reflections and opportunities. Social Science & Medicine, 73(6), 793-800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.07.014

- Knei-Paz, C. (2009). The central role of the therapeutic bond in a social agency setting: Clients’ and social workers’ perceptions. Journal of Social Work, [2], 178-198. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017308101821

- Levin, C. (2013). Socialt arbete som moralisk praktik. [Social work as moral practice]. In S. Linde & K. Svensson (Eds.), Förändringens entreprenörer och tröghetens agenter: människobehandlande organisationer ur ett nyinstitutionellt perspektiv (pp. 25-41). Stockholm: Liber. The entrepreneurs of change and the agents of interia: human service organisations from a new institutional perspective.

- Lipsky, M. (2010). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services(30th anniversary expanded edition). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Michailakis, D., & Schirmer, W. (2010). Agents of their health? How the Swedish welfare state introduces expectations of individual responsibility,. Sociology of Health and Illness, 32(6), 930-47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2010.01262.x

- Molander, A., & Terum, L. I. (2010). Profesjonsstudier – en introduksjon. [Studies in professios – an introduction]. In A. Molander & L. I. Terum (Eds.), Profesjonsstudier (pp. 13-27). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. Studies in professions.

- Mosesson, M. (2000). Intervention. In V. Denvall & T. Jacobson (Eds.), Var- dagsbegrepp i socialt arbete. Ideologi, teori och praktik (pp. 223-240). Stockholm: Norstedts Juridik. Everyday concepts in social work. Ideology, theory and practice.

- Nelson, R. R., & Winter, S. G. (1982). An evolutionary theory of economic change. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. London: Sage.

- Perrow, C. (2014). Complex organizations: a critical essay (3 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Rexvid, D., Evertsson, L., Forssén, A., & Nygren, L. (2014). The precarious character of routine practice in social and primary health care. Journal of Social Work, 15(3), 317-336. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017314548121

- Shanteau, J. (1992). Cometence in experts: The role of task characteristics. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 53(2), 252-266. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(92)90064-E

- Smith, M., Gallagher, M., Wosu, H., Stewart, J., Cree, V. E., Hunter, S., Evans, S., Montgomery, C., Holiday, S., & Wilkinson, H. (2012). Engaging with involuntary service users in social work: Findings from a knowledge exchange project. British Journal of Social Work, 42(8), 1460-1477. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcr162

- SOU 2003:30. (2003). Läkare i allmän tjänst [Doctors in general practice]. Stockholm: Fritzes offentliga publikationer. Retrived from https://data.riksdagen.se/fil/09A427CB-E9AD-4AF4-9E40-0A731DD99071

- Socialstyrelsen. (2004). Socialt arbete med barn och unga i utsatta situationer: förslag till kompetensbeskrivningar [Social work with children and young people in exposed situations: proposals for competence descriptions]. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen.

- Svensson, G. (2015). Rättslig reglering av människobehandlande organisationer. [Legal regulation of human service organisations]. In S. Johansson, P. Dellgran, & S. Höjer (Eds.), Människobehandlande organisationer. Villkor för ledning, styrning och professionellt välfärdsarbete (pp. 166-193). Stockholm: Natur och Kultur. Human service organisations. Conditions for management, control and welfare work.