Olli Rissanen, Petteri Pitkänen, Antti Juvonen, Pekka Räihä, Gustav Kuhn and Kai Hakkarainen

How Has the Emergence of Digital Culture Affected Professional Magic?

Abstract: We examined how the emerging digital culture has affected magicians’ careers, the development of their expertise and the general practices of their professions. We used social network analysis ( n=120) to identify Finland’s most highly regarded magicians (n=16) representing different generations. The participants were theme interviewed and also collected self-report questionnaire data. The results revealed that digital transformations have strongly affected the magical profession in terms of changing their career paths and entry into the profession. Magic used to be a secretive culture, where access to advanced knowledge was controlled by highly regarded gatekeepers who shared their knowledge with a selected group of committed newcomers as a function of their extended efforts. Openly sharing magical knowledge on the Internet has diminished the traditionally strong role of these gatekeepers. Although online tutorials have made magical know-how more accessible to newcomers, professional communities and networks play a crucial role in the cultivation of advanced professional competences.

Keywords: Digital culture; expertise; gatekeeping; internet; professional magician; professionalism

The purpose of this article is to examine how the emergence of digital culture has affected professional pursuit of magic. Magic is a performative form of art and entertainment that relies on sophisticated competences cultivated across years of training (Rissanen, Palonen, Pitkänen, Kuhn, & Hakkarainen, 2013; Rissanen, Pitkänen, Juvonen, Kuhn, & Hakkarainen, 2014). Magic diverges from traditional creative professions in that it lacks formal education, formal credentials, and institutionalized career paths. However, magic shares important professional characteristics, such as earning a living through magical performances, having recognized, yet informal professional competences, belonging to a collegial network of trained experts, and practitioners identifying themselves as belonging to skilled professionals in the field. Magicians are usually self-employed autonomous entrepreneurs and constitute an important part of the creative sector of society (Lindström, 2015; Svensson, 2015). Whilst it is questionable as to whether magicians are a real profession, we consider magic a creative occupational group with a high degree of professional competence and autonomy, which can easily be compared to other performing artists.

Expertise and professionalism in the field of magic

By relying on cultivated professional knowledge and skills, magicians earn a living by performing in front of physical or virtual audiences. Reaching top-level expertise relies on the sustained cultivation of personal competences, which are typically guided by mentors. Top-level magicians reach their expertise in similar ways to other creative professionals (e.g., writers, actors) and sports masters (Ericsson & Pool, 2016; Ericsson & Starkes, 1996; Larsen, 2016). The field of magic is interesting because the process of becoming a professional magician is less structured and occurs without formal organized training and education. Professional magicians invest vast amounts of time and resources into developing their skills. In accordance with other domains, it takes approximately 10 years of cultivating skills and competencies before one can become an expert magician (Rissanen et al., 2013). The field of magic involves developing professional methods and techniques for deliberate human deception. Highly regarded magical performances rely on a sophisticated understanding of human cognition, especially thinking and perception (Kuhn, Almani, & Rensink, 2008). Developing this professional expertise is a multi-faceted process involving interdependent technical (mastering tricks), artistic (developing performative programs) and entrepreneurial (making a living) competencies. These competences are further developed through progressive and target-oriented deliberate training (Rissanen et al., 2013).

The magicians’ working field can be seen as a battleground on which continuous professional claim-making and negotiations takes place. According to Bourdieu (1996), artistic professionals and stakeholders safeguard their specific interests and struggle for influence through subconscious processes of symbolic boundary work. A field is an enclosed social system of positions occupied by specialized agents and institutions, struggling for common field specific resources, assets and acknowledged reputation (Bourdieu, 1986, 1993a; Broady, 1990, p. 270; Gustavsson et al., 2012, p. 13). In fields of creative entrepreneurship, reputation-related symbolic capital is arguably more valuable than economic capital. In the magician’s world, the agents are magicians, performance sellers, show producers, TV producers, arrangers of competitions, and critics writing about their performances and members of magic associations. In the magicians’ autonomous subfield, there is also a division between well-known “old school” magicians and younger performers, who lead target attacks towards the “establishment,” aimed at acquiring the sub-field’s valued assets. This is where the strategic importance of the name, the CV, the personal branding, habitus or other forms of self-commodification become valuable.

Digital transformations in the field of magic

Magic is one of the oldest forms of entertainment, and throughout history, magicians have embraced new forms of technology (During, 2002). Over the last 10 years, major advances have also been made in our scientific understanding of magic (Rensink & Kuhn, 2015), and insights into the cognitive mechanisms behind these principles have recently been combined with developments in artificial intelligence to produce new types of magic tricks (Williams & McOwan, 2014) as well as new technologies that use principles common in magic (L’Yi, Koh, Jo, Kim, & Seo, 2016). These changes do not only concern magical instruments and tricks but also collegial relations between what were previously relatively isolated actors as well as relations between magicians and their audience. Personal social networks play a critical role in fields, such as magic, where there are no formal training and educational resources (Gruber, Lehtinen, Palonen, & Degner, 2008; Nardi, Whittaker, & Schwarz, 2000; Rissanen, Palonen, & Hakkarainen, 2010). Currently, the pursuit of professional magic is embedded in a multifaceted network of expert magicians who engage in a plethora of activities such as conferences, workshops, and online magic forums.

The digital culture has radically transformed the power relations within the professional field of magic. Magic has traditionally been a closed and secretive subculture, where knowledge has only been transferred between individuals who have established a significant level of trust in each other. The necessarily secretive nature of magic implies that magicians were required to closely guard most of their knowledge about their own magic tricks. Although access to this secretive information used to be largely restricted to expert magicians (Rissanen et al., 2014), the digital culture in general and Internet, in particular, have changed the ease with which this information can be accessed. Before TV, videos and the Internet, learning magic relied on a fragile mentor relations and the support of senior experts who held strong gatekeeper positions. These gatekeepers (Bourdieu, 1993a; 1993b) acted as inspectors, evaluating the newcomers’ competence and willingness to enter the magicians’ profession. For newcomers, this trust was established through sustained efforts and socially recognized achievements. In the past, geographical constraints made it difficult for newcomers to find an adequate mentor, and gaining access to advanced knowledge was a slow process; such individuals depended upon a high level of trust that they gradually obtained through informal networking efforts (Rissanen et al., 2013). In this article, we examine how the digital culture has changed the role of the traditional gatekeeper guarding this secret magical knowledge. The Internet has created a so-called ‘amateur pro’ culture, where professional knowledge across all domains, including magic, is available to anyone (Gee & Hayes, 2011); this has radically changed the culture of magic and associated power relations. Although sharing complex professional knowing may still require significant effort and motivation, the digital culture has significantly lowered the cognitive cost of sharing one’s knowledge (Shirky, 2010). Such sharing provides social recognition of one’s accomplishments, and there is a strong motivational incentive for doing so.

In the present article, we examine the effect of the emerging digital culture on professional pursuit of magic. We interviewed highly regarded Finish magicians to explore how the digital culture has changed their professional pursuits. We examined their reflections on the changes that have modified the processes of becoming a professional magician in different areas. The research questions guiding our investigation are as follows:

-

How has the digital culture changed the role of the traditional gatekeeper, whose task it was to guard secret knowledge?

-

How have online magic tutorials changed the way new magic tricks can be learnt, and what are their limitations?

-

How has the digital culture changed the entrepreneurial activity of magicians representing different generations?

Methods

P articipants and the context

We used four bodies of dataset to analyse how the digital culture has transformed the culture of professional magicians. Firstly, the social networking questionnaire was administered to 120/148 well-known Finnish magicians and other influential background people (response rate: 81%; age distribution: 17–86 years) (Rissanen et al., 2010). Secondly, on the basis of the social network data, we identified 16 professional magicians as subjects for semi-structured thematic interviews focused on the effects of digital technological transformations not addressed in our earlier published studies (Rissanen et al., 2013; Rissanen et al., 2014). Thirdly, we carried out supplementary interviews on 10 of the 16 previously interviewed individuals since the first round did not provide sufficiently detailed information. All interviews were analyses as one integrated dataset. Fourthly, 16 magicians were sent a questionnaire about how they currently use digital technologies, but since one respondent who had ended his career as a magician data from this participant was excluded.

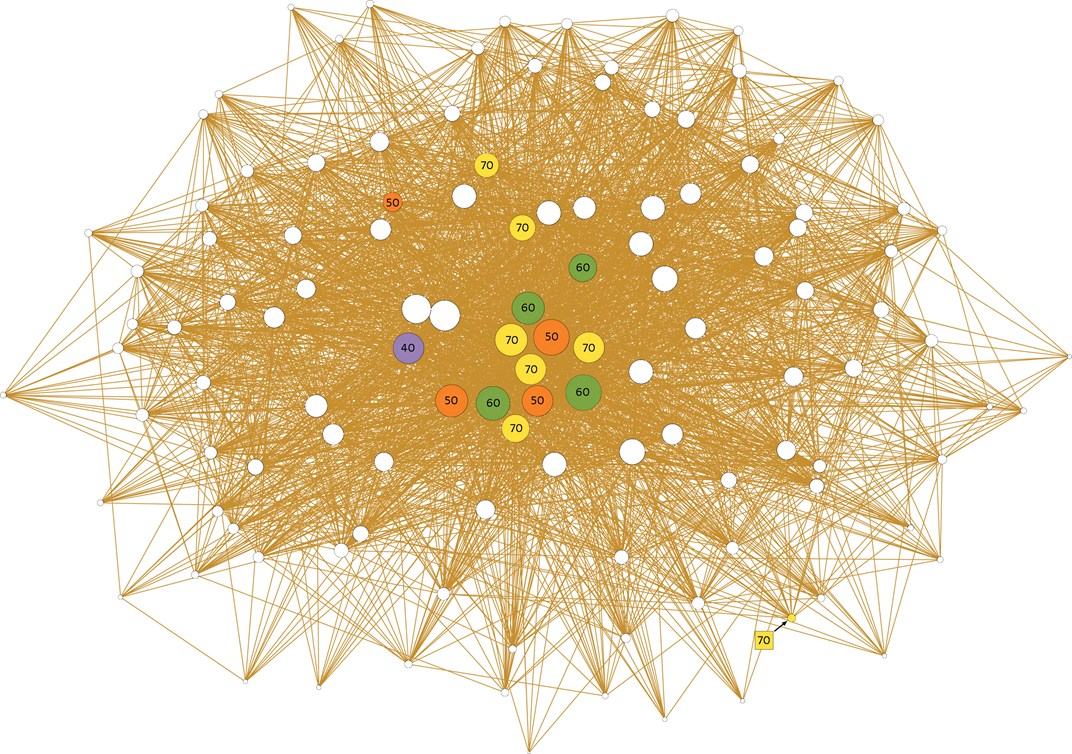

Figure 1 presents a social network graph representing the social recognition of magic expertise; the participants selected for the interviews to represent different generations are marked by coloured nodes. The magicians’ peer evaluations were used to create indicators for nominating prominent magicians (i.e., number of peers recognizing their professional accomplishments). The analyses indicated that social recognition was not correlated with age. Most of the magicians were males. We, therefore, decided to include two female magicians in the interview sample to compensate for the gender imbalance. Although one of the interviewees was some-what peripherally located in Figure 1, the magician was selected because of his or her “rising star” status in the industry. The overall sample of participants was selected for analysis because the interviewees were earning a living as highly regarded professionals in the field. The interviewees represented different generations: one was born in the 1940s, and the others were born in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. In order to protect participants’ anonymity (M1–M16), some of the information (e.g., gender) is not reported in the article. The interviews were carried out in Finnish, and the Finnish authors assumed responsibility for analysing the qualitative data.

The size of the nodes was determined according to the degree of regarded professional recognition. White nodes represent a magician working in the field (n=104), and coloured nodes represent highly regarded participants (n=16) selected for interviews according to the different decades (1940s–1970s) in which they were born (1940s: lilac; 1950s: orange; 1960s: green; 1970s: yellow).

Data acquisition and analysis

Various aspects of the magicians’ professional expertise were examined through the semi-structured interview (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009). The interview was designed to address the participants’ ways of experiencing technological, social and cultural changes in the magical field as well as their use of the Internet. We addressed nine main themes considered to be relevant for assessing the transformation of the culture of the professional pursuit of magic: (1) beginning a career as a magician, (2) the nature of the magical performances, (3) respecting the magician’s profession, (4) facing the professional challenges, (5) magic as a profession, (6) the emergence of magical societies, (7) entrepreneurial issues, (8) the role of digital culture and (9) anticipated future of the field. The length of the interviews ranged from 57 minutes to three hours and 37 minutes. The length of all of the interviews together was 41 hours and 28 minutes.

The transcribed interview data were qualitatively analysed using the ATLAS.ti 6.2 program (see http://atlasti.com/). The program allows transcribed interview text to be presented in one column, which facilitates identifying and marking qualitatively different text segments. The coding of each text segment is presented in another column. Initially, the interviews were read several times to get an overview of the central contents and themes. Subsequently, the data were analysed to find common themes and distinguishing features in accordance with the data-driven approach (Frank, 1995). The analysis was partially data-driven and partially theory-informed in nature.

Categorisation of the data was conducted independently by two coders who repeatedly met, compared observations and resolved disagreements. Next, the text segments relevant to the purposes of the present investigation were categorized into the same hermeneutic category to exclude irrelevant material, such as detailed personal recollections of one’s career. On the basis of the coders’ mutual discussions, the data were categorized according to three main themes: (1) cultural changes, (2) digital culture, and (3) entrepreneurial transformations. Investigating changes in the culture of professional magic (1) emerged themes related to gatekeeping and restricted knowledge closely related to Bourdieu’s field theory. Digitalization was connected with the emergence of knowledge sharing culture. The development of digital culture (2) broke importance of gatekeeping and knowledge control because formerly secret knowledge has become available to everybody.

Each category was analysed in detail to identify sub-themes. Interesting observations occurring during the analysis were documented in the associated to new ATLAS.ti codes. Finally, the data were screened for quotations and compressed descriptions regarding various aspects of the magicians’ activities. The quotations were selected at research meetings to accurately describe the findings by using the participants’ own words. Table 1 provides an example for qualitative analysis of the data regarding gatekeeping and knowledge control.

Table 1.

An example of categorizing gatekeeping related themes.

|

Data except |

Compressed content |

Subordinate categories |

Superordinate category |

Main category |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Theme 1. Cultural changes |

Yes it was quite a difficult situation, when there was no place where you could receive instruction and there was not Internet in those days. When the books were read, it was a difficult stage to get forward. |

Difficulty of getting information about magic. |

The limited availability of professional material. Information restricted to trusted newcomers. Controlling newcomers level of interest and commitment. |

Gatekeeping resulted to restricted access to magical materials and information. |

The connections between Bourdieu's field theory and the digital culture. |

|

Then it was also so, that no magic tricks and gadgets were sold to you until you became somehow known, that everyone knew that you are a magician as a hobby. |

The gadgets and tricks were only sold to known newcomers. |

||||

|

If you started by calling xxx and tried to order Chinese Rings, he didn't sell them to you. You had to be a hobbyist for some time to be able to buy some of these fine, better tricks. |

Newcomers have to indicate serious hobbyism for getting better tricks. |

||||

|

He didn’t send the Joker or the magic trick when you tried to order something. He could even say that this trick is not sold to amateurs. |

Certain tricks were not sold to amateurs. |

||||

|

Theme 2. Digital culture |

After the YouTube became available, you can find anything there if you hit the right search terms. This has created an illusion, that knowing is the same as being able to perform tricks. When you know some secrets, of course does not imply you can perform them. But gaining knowledge and information is much faster than in the old days. |

The easiness of getting information from YouTube. Confusion between knowing and competence. The relation between the books and video. |

Accessing knowledge and instruments became easier. Magical information spreads freely after the emergence of internet. The role of YouTube in finding secrets. |

The digital culture resulted to free distribution of magical knowledge and knowhow. |

|

|

The magician ship somewhat loses its glamour or mysteriousness, when all the information about magic and tricks are so easily available, and it doesn’t require much efforts and trouble. You just check on YouTube, and there are all the magicians in the whole world. In the old days, you had to do a lot of hard work before you could reach at least some unstable, shaking VHS-video, or when a magician performed on TV, we waited weeks before we could see it. |

The magical knowledge is easily available on the Internet. It used to be necessary to do tremendous amount of work for finding relevant information. |

||||

|

In principle, anyone can find any trick on YouTube and maybe even find a hundred versions. He can watch it so many times that it (secret) somehow opens up. Earlier this was impossible, we had no chance of getting information about the tricks at all. |

The easiness of discovering the secrets of any trick. |

All of the targeted participants (n=15/16) responded to the questionnaire aimed at examining the role of digital technology and culture in the professional activities. One professional magician had ended his career as a magician and was therefore excluded from the analysis. The magicians were sent an e-mail asking them to answer the Google Form questionnaire online. The questionnaire included two main themes: First, the respondents were asked to assess the significance that digital technology and associated applications had in their work as professional magicians. The respondents could choose one or more of six possibilities, including (1) finding information about magic, (2) becoming familiar with the work of other magicians, (3) improving their own performance, (4) improved marketing or sharing of performances with the audience, (5) creating novelty or (6) no particular significance. This section included 20 items. Second, they were asked to assess the level of intensity of engaging in different types of digitally mediated activities in their professional lives. This section included 13 items addressing various digital applications, such as e-mail, YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook. Each item required assessment of use on a seven-step scale: (1) never, (2) once or twice per year, (3) monthly, (4) weekly, (5) daily, (6) many times per day and (7) continuously.

Results

The results section is organized as follows: Firstly, we explore how digitalization has affected ways of transmitting magical knowledge and especially examine the changing role of gatekeeping in the professional pursuit of magic. Secondly, we examine how online tutorials have changed the learning of magic competences. Thirdly, we analyse how the transformed environment has affected the magicians’ entrepreneurial activities.

How has digital culture changed the role of the traditional gatekeeper?

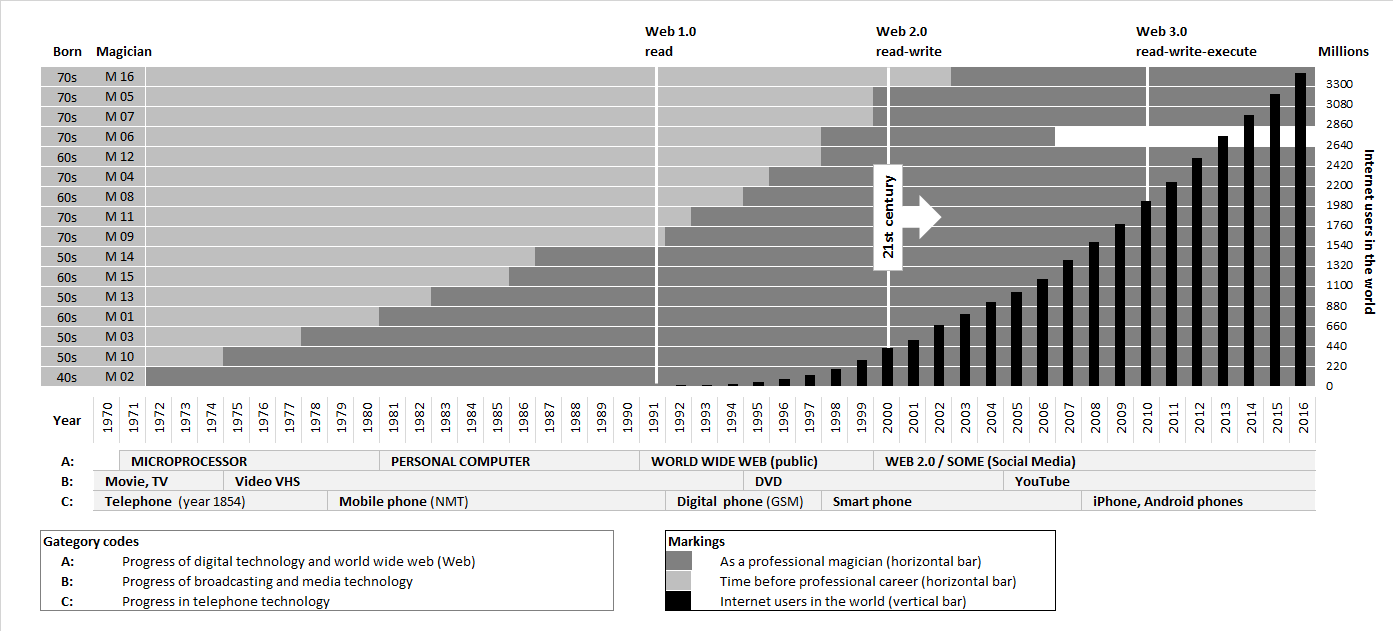

We examined the effect of the digital culture on professional practices by asking the interviewees to reflect on the corresponding themes included in the self-reporting questionnaire (n=15). Our sample represents several generations of magicians. Between 1970 and 2016, the most important sources of professional information were obtained from books, TV, videos, DVDs, PC programs, mobile devices, the Internet and associated digital applications. The technological changes followed each other in 10- to 20-year periods, and the magicians were forced to adjust to the socio-technological infrastructure changes in their professional activity. Figure 2 relates to the interviewees magic careers with digital transformations in the field.

Figure 2.

Relations between professional careers of the interviewed magicians and technological advances from 1970 to 2016 (ICT Lounge, 2016; Internet Live Stats, 2016; Rissanen et al., 2013).

Our analysis revealed that the emergence of books, TV, videos, DVDs, and social media significantly affected ways of transmitting professional knowledge and documenting and sharing magical performances. The emergence of video-based culture, which was followed by DVD technology in the following decade, replaced the role of books as the main pathway for learning about magic tricks and performance culture. Magicians from younger generations have been socialized to work through TV, DVDs and Internet applications, such as YouTube, from the very beginning of their careers. In the past, most magicians solved problems by discussing them personally with other magicians or through engaging in critical self-reflection. Currently, the Internet is considered to be the most important means of finding information (n=15/15), getting to know the work of others (n=14/15), marketing and sharing performances (n=14/15), sharing one’s own performances (n=12/15) and creating new tricks (n=10/15).

The digital transformation entailed radical changes in gatekeeping practices. In the past (up to 1980s), the best-known magicians and magic associations (e.g., the Finnish Magic Circle) acted as gatekeepers in terms of deciding who was allowed to obtain the magicians’ secrets, join the associations and participate in their joint meetings. Gatekeeping enabled the established magicians to protect their secrets and carefully select collaborating partners and those who got to know the secrets of their tricks:

I was trying to subscribe to the Jokeri-magicians’ journal, which could not be done without being a “real” magician. Then, Solmu (famous highly regarded magician) recommended me, and I got the journal. Another time, I tried to become a member of the Performing Artists association, but I was too young, probably the youngest ever selected as a member, but that was not possible before Solmu’s recommendation, which opened up the possibility of membership for me. (M6, 1970s)

A novice magician had to demonstrate to the society, through his or her own actions, including success in a contest and highly regarded public performances, that he or she was sufficiently suitable and skillful to enter the association’s membership. The gatekeepers’ control functioned on two levels: control of the individuals and control of the materials. Before the time of the Internet, information was shared piece by piece on the basis of merit:

The older magician told me about the magicians’ journal Genii, and he told us the address of the journal, and we got in touch with it and were able to order it, noticing that there are hundreds and hundreds of magic stores around the world. It all came in small pieces: one magician told you this, and another showed you that to get one step forward in magic. (M10, 1950s)

In the earlier decades, magic props were sold (or shared) only with those whom the older magicians knew to be real enthusiasts and committed to the practice and cultivation of their competencies. If you wanted to order Chinese Rings, for instance, that was not possible until you had practiced enough and had been a hobby magician for a long time.

No tricks or other gadgets were sold to you until you had been known somehow as a hobby magician. (M7, 1970s)

The digital transformation changed the role of gatekeeping. The power of the former gatekeepers (professional magicians) dwindled because everything was suddenly available via the Internet, and anything could be studied without their approval. In the past, magicians commonly solved problems by discussing them personally with other magicians or through engaging in mere self-reflection. Today, the Internet has become the primary place from which answers about professional problems and inquiries are sought. Although one can easily acquire information from the Internet, it does not replace the expertise of fellow magicians. For knowledge-sharing and protecting professional secrets, magicians have created trusted partnerships with their colleagues.

I don’t ask for advice anymore, but if do I ask, I get the advice—maybe I should ask more. I don’t know. There are some colleagues with whom I discuss, maybe one to three people with whom I discuss the techniques and different methods, etc. (M16, 1970s)

The emergence of the digital culture unlocked all of the secrets of the magic profession; this may potentially undermine the very basis of the magical professions. However, there is a very low level of quality control, because all of the tricks and their secrets are available and can be bought online by virtually anyone. Simply buying magic tricks and knowing their secrets does not, however, turn people into professional magicians. Many of the interviewees were worried that, in many cases, practitioners’ know-how remains superficial because true mastery of magic requires a deeper understanding that is only gained from the inner circles of the magic community. This only becomes possible by entering the magic associations, participating in international conferences and by establishing confidential contacts and relations with real professionals. While the Internet has made much of the material available to the masses, the gatekeeping structures are in some way still present today, although in a more hidden form.

Online magic tutorials change to learn magic

Learning magic increasingly takes place through digital networks that provide tools and applications for easily appropriating magical know-how. The interviewees strongly highlighted the significance of YouTube for learning magic tricks and for sharing magical competence. All of the respondents used YouTube (n=15/15) to learn about other magicians’ work. They also commonly used it to find information and marketing (n=13/15) as well as to share their performances with new audiences (n=12/15). YouTube offers a vast library of magic performances and tutorials that magicians can use to learn new tricks and methods. YouTube provides easy access to vast bodies of information, and many novice magicians use it as an online portal to access magical knowledge. Learning practical aspects of performing magic tricks (i.e., how a trick should be implemented in practice) becomes much easier with YouTube compared to written instructions. Our interviewees were accomplished magicians who had already acquired their expertise before the invention of YouTube. Consequently, they did not talk extensively about personal experiences learning tricks via online tutorials but nevertheless acknowledged the importance of online tutorials for newcomers.

Learning tricks from YouTube has substantially and qualitatively transformed the way magic is learnt. Although the availability of a wide variety of magic tricks on the Internet facilitates learning many aspects of magic activities, the interviewees highlighted that its usage could also lead to more shallow professional competence in terms of recycling ready-made tricks and performances:

And then there is an embarrassing amount of everything available, so you don’t know where to start. It was somehow good that at that time there were not so many opportunities, and one had to focus on only a few things. Now there is this fast food phenomenon: right away, to the next and next, which created new challenges. (M5, 1970s)

The vastness of the online resources does not compensate for their lack of quality, and it is often difficult to use the information provided effectively:

Knowing a trick is not the same as mastering it. When a trick is directly taken from the Internet as a whole, it easily becomes a clone rather than one’s ‘own thing’. A trick should be personal, and self-invented, and it should include your own stamp on it. (M16, 1970s)

The above examination indicates that the digital culture has significantly changed how magic is learnt as well as many other aspects of the professional activity. While heavily inspired by the new possibilities that the digital culture provides, magicians also use traditional media such as books and journals in their professional activity. All of the interviewees still use books to discover information about magic (n=15/15), to get to know the work of others (n=15/15), to find inspiration for their performances (n=12/15) and to create new performances (n=12/15). Other print sources were also considered important in creating new performances (n=12/15). Magic journals were seen as important for finding information (n=14/15) and getting to know about the work of other magicians (n=13/15), and in this sense, digital and traditional media complement one another. Many magicians expressed worry that so few books are currently used for studying magic. They felt that when novices move too quickly to DVDs and YouTube for easy access to magical knowledge, professional competencies may not develop, or their development gets truncated. As stated by M16 (1970s), books are more useful, even when read online, because “when using a book, you have to be more creative.” A book, whether it is a hard copy or digital, assists in the process of developing new tricks and encourages the reader to reflect on an issue from many perspectives. In M7’s view,

If you read something from a book, you have to build a picture in your head yourself, and it may happen that this picture changes from the one which the writer has in mind while writing the text (M7, 1970s).

It is challenging for a novice to manage the huge amount of information that is so easily accessible on the Internet. Where an experienced magician is able to use the Internet to support the continuous development of professional competence, it can be a trap for inexperienced magicians. Just like in any other network store, the ordered item is not, in the field of magic, always as expected or promised:

And of course, if you are a beginner, it will be easier to fool you on the Internet. You see a trick, read the manual, and order it just to see— it wasn’t what you were promised. Now I have learned to see what is worth ordering. (M5, 1970s)

The interviews worried that because the readily available professional resources are often not at all curated, they can lead to wider spreading of shallower professional competences. When there is a large selection of tricks available, it is harder to make decisions about how to begin, advance, and create innovative performance programs. Increased autonomy of magicians may lead to aimless jumping around instead of deepening expertise. Limited availability of professional knowing forced practitioners of the field to put tremendous effort for developing their skills and competences.

How has the digital culture changed the magicians’ entrepreneurial activity?

The present section addresses the changing role of marketing and visibility in pursuit of professional magic in the digital culture. The results revealed that the technologically mediated practices were heterogeneous rather than straightforwardly following generational lines of progression. Almost all of the participants use the Internet on a daily basis (n=12/15), especially for information seeking. All of the interviewees recognized the importance of the Internet and social media, and they all used email and had their own websites. Everybody had a Facebook profile, but only a few of them actively used it to keep up with contacts, update their statuses or to market themselves. Some of the interviewees had their own personal Facebook pages as well as a separate magician profile, which they used for marketing and branding. Five magicians shared their work and updated their statuses on a weekly basis; seven magicians used YouTube monthly, and eight magicians used it weekly.

Variation in Internet skills and uses within each generation was often bigger than the variation between the generations. Yet, the results revealed that the three youngest magicians included in this study (M5, M7, and M16), who were born in the mid-1970s, took the most advantage of technology. Internet and social media use was reportedly more natural and easy for these younger participants than it was for the older generation. One magician born in the 1970s reported using Facebook and Twitter intensively when making performance contracts. Another talked about his versatile use of web applications:

Yes, I use them all the time. I have a mobile phone with Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, a homepage and an official page, and that is quite enough. I am most active on Facebook, but I also go directly to Twitter when I upload something so that I don’t have to put everything in two places. Sometimes I put a funny picture on Instagram, but not very often. (M16, 1970s)

The interviews indicated that using the digital resources was more natural and easy for participants representing the younger generations than it was for the older ones. However, the data indicated that some of the participants representing the older generation were very active on the Internet, whereas some of the younger participants were not. A magician born in the 1940s sees the technology not as a threat, but as an adjunct for the profession:

Digital technology is no threat, from my point of view—rather, I see it as new possibilities. All these technological things have taken things forward and brought new approach to the business. We should still always remember that magicians’ skills are mostly, in principle, manipulation. The ability to perform miracles is at such a high level that it cannot be beaten with any kind of technology or electronic gadgets. The skill of performing cannot be replaced with these devices. We must remember that they are servants, not masters. (M2, 1940s)

Another magician from the older generation sees social media as a necessity for the younger generation. He does not consider this to be important for himself because his customers and the amount of engagements he gets have stabilized over his long performance career:

When talking about social media today, if you are on top of your professional activity, you just have to be present in the media. For the younger generations, it is a must. Of course, they have the abilities, as they have grown up with social media. There is a certain difference between the generations in this matter—if you belong to the young generation, I think they all are inside the media. (M10, 1950s)

Interview analysis revealed that the digital culture has transformed all of their entrepreneurial activities. All of the interviewees had a Facebook profile, but only a few of them used it actively to keep up contacts or to market themselves. Some of the interviewees had both personal Facebook pages and a separate magician profile that they used for marketing and branding. Interviewee M16 reported that advertising has become more challenging, somewhat more aggressive in nature and competition between magicians tighter. One has to continuously keep up people’s interest and ensure continuous visibility of one’s accomplishments:

Now we have to be on social media all the time and advertise, put up links and share them—that’s the way it has changed. It has become more demanding because all the time you have to be thinking and advertising this and that here and there. It has become more complicated—earlier it was simpler and easier. We only had the Internet pages and cards, and that was all. Now you have to do a lot more yourself to keep the interest up and [to keep] people knowing about you. (M16, 1970s)

The magicians reported that they constantly have to be reachable in a way that they did not in the past. If they do not respond to an offer quickly, the customer selects another performer. Because of digital technology, life has gradually become faster and faster. In addition, the magic field is affected by its fragmentation, an increased number of magicians and the fact that there are many other performers, such as stand up comedians and performing musicians, competing for the same performance opportunities:

It has changed a lot. It has become quicker as Internet pages have become even more important. Video has become very important because it shows what kind of things you are able to perform. It has also become more aggressive in the way that the competition uses dubious mediums such as running off at the mouth, for instance, in the media. (M7, 1970s)

YouTube offers the possibility to quickly reach a large audience, and revealing magic tricks online can attract a large number of online visitors. Magicians constantly have to upload new material to remain relevant (e.g., news, pictures or videos of performances), and while Facebook is an important marketing tool, other online forums are equally important, as they increase one’s visibility on Google searches (e.g., blogs, Instagram, YouTube, Twitter). Social media enables effective marketing and branding, as the magicians’ homemade videos may get a large number of views through YouTube and social media. For example, the Finnish magician and mentalist Jose Ahonen (born in 1979) gained a worldwide audience through social media using one single 1 minute and 49 seconds video clip called https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VEQXeLjY9ak. The aim was to reach 10,000 views for the video. It took less than 24 hours to get 320,000 clicks, more than five million clicks in three days and more than 10 million clicks in one week (Sirén, 2014). Furthermore, Internet services provide meta-information about potential customers that can be used for marketing. For the younger generation, this is a commonplace everyday activity. It is a truly novel phenomenon in the world of magic that a viral YouTube video can almost instantaneously lead to international recognition.

Discussion

We examined how the digital culture has transformed the professional practices of prominent Finnish magicians who represent generations born between the 1940s and 1970s. We used semi-structured interviews and self-reporting questionnaire to explore the Internet’s impact on various aspects of professional magic. The emergence of TV, videos, personal computers, DVDs and especially the Internet has considerably changed the professional pursuit of magic. Although all the interviewees were born before the emergence of the digital culture and changes in the associated technologies, these technological advances have significantly affected their professional work. Simultaneously with technological transformations, the nature of magic performances has changed from stage magic performed with background music to close-up magic and mentalism, both of which involve more improvisation and audience interaction. The rise of the digital culture and associated online resources has transformed the traditional methods of learning magic through personal contacts and reading books. The Internet enables immediate access to extensive information and online tutorials, allowing for the quick spread of ideas, tricks, and performances.

The results confirmed our expectations that practitioners in the field openly share a great deal of their knowledge through video-recorded performances and YouTube videos, which may significantly facilitate newcomers’ learning and development. Gatekeepers no longer play as important a role as they used to – a great deal of information and instructions are now easily available on the Internet. Our results revealed that online magic tutorial videos have transformed how magic is learnt, and YouTube videos have drastically transformed the magician’s learning experience. In the past, most sleights had to be learnt from books, and describing these complex motor movements through static pictures and text alone was very challenging. The digital culture now allows newcomers to learn magic tricks by watching online video, as well as copy entire magic routines, which greatly facilitates the learning experience.

The digital culture has affected practices of becoming and maintaining membership in the magician’s professional community. Newcomers may enter the field by gaining a reputation through their public and online performances without necessarily initially earning the trust and respect of the senior magicians and magic associations. The interviewees reflected on the various ways that magical activity is valued, from the initial efforts of the seminal magicians widening the scope of magical performances and shows to the present Internet-mediated global culture. One example of modern magic is the internationally recognized Finnish magician Janne Raudaskoski’s performance of https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r92vGFSN5Fo, which connects techniques from theatre and movies with magic, technology, and clowning.

Professional conditions are related to strategies and negotiations of different interests and therefore are a part of historical change (Brante, 2010). In the digitalized field of professional magicians, there appear to be new types of struggles of recognition and associated symbolic capital. Some of the old-timers felt that the easy access of professional knowledge in the digital culture might lead to shallower professional competencies. Many of the interviewees highlighted risks of openly sharing magical knowledge; it may lead to underdeveloped performances and shows. The complete availability of magic knowledge may harm the excitement of magic shows and lead to excessive copying of tricks and performances. There are, however, no shortcuts to become a respected professional magician. Technical skills and the laws of performance have remained the same, and they form the indispensable basis of becoming a professional magician. Many veteran magicians consider the open mode of knowledge sharing to be at odds with an artistic ethos valuing hard work, individual initiative and originality in the appropriation of tradition. According to such views, the accelerated digital circulation of magicians’ secrets may ultimately imperil the practice of magic itself (Jones, 2011).

Because the Internet involves infinite amounts of potentially relevant information, it is challenging to find material suitable for developing one’s own creative performances. The interviewees’ skepticism regarding the value of digital culture and associated capabilities of junior magicians may at least partially reflect their efforts of demarcating professional boundaries. According to Lamont and Wiseman (1999), the dangers of revealing secrets on the Internet are easily exaggerated, as the methods have also been exposed in books and television.

Although digitalization has radically altered the secretive culture of professional magic, the magic community still intends to protect intellectual property rights of professional magicians (Loshin, 2010). Although it is acceptable to share and adapt a trick developed by a fellow magician, copying another magician performative style (or whole performance programs) is considered inappropriate. Although magicians freely share basic and less advanced tricks, truly innovative and advanced material used by top performers is usually shared through informal channels. This indicates that advanced professional knowledge in the field is still protected. The innovative magicians put systematic effort into improving the new tricks they learn and adapting them to fit their personal style of performance. In many cases, professional magicians keep a novel trick or performance as an exclusive part of their performance repertoire and share the secret with colleagues only after personally capitalizing on it for a while. It follows that many mechanisms of professional cultures, such as proprietary knowledge, are still prevailing in the field of magic.

Furthermore, the interviewees reported tailoring their performances according to the audience and closely interacting with them. The digital culture opened up new channels for marketing their activities and branding themselves as representatives of certain magic styles. They could build their fame through constant publicity on social media. In this more competitive environment, a magician must always be reachable. The technological developments have also affected the professional magicians’ entrepreneurial activities in terms of making their practices visible through social media and the Internet, and by allowing them to keep in contact with their audiences. The gatekeepers, whose position in the field of magic has already has been widely established, were able to limit admission to the magicians’ club earlier on, but today, their influence has changed and become largely redundant mainly because of the Internet.

Conclusions

Reaching professional level requires years of professional training and acquisition of a multifaceted body of cognitive, motoric, social, and performance-related know-how. In this regard, magic shares important characteristics with other fields of creative professional expertise. However, magic diverges from many other fields of creative work in that it entirely relies on informal cultivation of professional competence without formal education or legislated credentials.

The professional community of magic relies on secret knowledge that has been challenged by information made available on the Internet. Magical associations guarded key secret, or at least esoteric knowledge of the field. Traditionally, the knowledge monopoly of established magicians functioned to control access to the field and advanced magical know-how. The digital transformations has made it much more difficult to gatekeeping and secure the “tricks of the trade.” The digitalization and the Internet may have undermined the very basis of professions.

Our results also illustrate that the professional communities and magical networks still play an important role in the development of professional competences. YouTube alone does not offer the beginner answers to the questions of where to start, and what to learn next. It does not provide novices the pedagogical key to cultivate professional competencies in magic and growing up to be members of the magic community. Although YouTube enables access to magic tricks and their secrets, it does not offer a comprehensive picture about what it takes to be a professional magician, which is much more than simply learning the tricks and the secrets. Although the interviewees felt that the digital culture provided many new possibilities, they were also concerned about easy access to this knowledge, the ill-structured nature of information repositories and the opportunities for building virtual reputations too quickly. The availability of a wide variety of magic tricks on the Internet will not necessarily deepen the magical know-how without deliberate training and support from expert colleagues (Rissanen et al., 2013). Although the ways of learning, and the places of performances changed, the peer support among the magicians still remains. This is an important finding that may be interesting for other professional fields as well.

The digital transformation has increased national and international visibility of magic and valuing it as an art form. There has been a radical shift from local experiences to continuous online presence. Many high profile magic shows attract huge audiences that follow performances in real-time and shared their expectations. Finnish magicians reach international audiences in a way that was not possible in the past. Magic phenomena attract a great deal of curiosity at the age on uncertainty and rapid societal changes that are hard for anyone to understand. Branding and high-profile visibility may be seen as efforts of the magical community to increase its symbolic capital and improve societal valuation of professional work in the area. Rather than undermining the magic profession, the digital transformation appears to strengthen and expand the field. After giving up tight gatekeeping the magical community has attracted many new practitioners as well as serious hobbyists and active followers.

Limitations of the study

The limitation of the present article was that we examined the effects of digital transformations within only one creative occupation, in other words, professional magic. The digital transformation are likely to have had similar impact on other creative professionals, such as writers, visual artists, actors, performing musicians, dancers, stand-up comedians, and directors. The present investigation involved interviewing a relatively small number of magicians. Yet the professional positions of the interviewees as the most highly regarded magicians were socially validated by relying on peer recognition of practitioners of the Finnish magical network. Because the field of magic is international, we do not have any reason to assume that interviewing only Finnish practitioners would have affected the results. The effects of digital transformations were analysed by relying on the participants’ retrospective reflections during the interviews. Overall, the interviews were extensive and provided content-rich material about various changes within the field. The interviewees represented different generations of magicians; this allowed accounting socio-historical transformations relevant for the emergence of audio-visual TV and video as well as subsequent digital culture. The older magicians had witnessed and also reflecting on radical transformations of the field across their lifespan whereas the younger ones necessarily had a historically more limited view and appeared to take the digital culture more as a given reality. Although more systematic ethnographic studies of professional practices in the field of magic would be useful, we maintain that the present data provided valuable scientific data regarding the effects of digitalization on the field of magic.

References

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241-258). New York: Greenwood.

- Bourdieu, P. (1993a). The field of culture production: Essays on art and literature. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1993b). Sociology in question. London: Sage.

- Bourdieu, P. (1996). The rules of art: Genesis and structure of the literary field. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Brante, T. (2010). State formations and the historical take-off of continental professional types: The case of Sweden. In L. Svensson & J. Evett (Eds.), Sociology of professions (pp. 75-119). Göteborg: Daidalos.

- Broady, D. (1990). Sociology and epistemology: On Pierre Bourdieu’s work and the historical epistemology. Stockholm: HSL Förlag.

- During, S. (2002). Modern enchantments. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Ericsson, K. A., & Starkes, J. L. (1996). Expert performance in sports. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Ericsson, A., & Pool, R. (2016). Peak. London: The Bodley Head.

- Frank, K. (1995). Identifying cohesive subgroups. Social Networks, 17, 27-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-8733(94)00247-8

- Gee, J. P., & Hayes, E. R. (2011). Language and learning in the digital age. London: Routledge. Hogan.

- Gruber, H., Lehtinen, E., Palonen, T., & Degner, S. (2008). Persons in the shadow. Psychology Science, 50(2), 237-258.

- Gustavsson, M., Börjesson, M., & Edling, M. (2012). Konstens omvända ekonomi: Tillgångar inom utbildningar och fält 1938–2008 (The reversed economy of the arts: Assets in educations and fields 1938–2008). Göteborg: Daidalos.

- ICT Lounge. (2016). History of ICT and technology timeline. Retrieved from http://www.ictlounge.com/html/timeline_of_ict.htm

- Internet Live Stats. (2016). Total number of websites. Retrieved from http://www.internetlivestats.com

- Jones, G. (2011). Trade of the tricks. Berkley, CA: University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520270466.001.0001

- Kuhn, G., Amlani, A. A., & Rensink, R. A. (2008). Toward a science of magic. Trends in Cognitive Science, 12(9), 349-354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2008.05.008

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). InterViews. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Lamont, P., & Wiseman, R. (1999). Magic in theory. Seattle: Hermetic Press.

- Larsen, L. T. (2016). No third parties: The medical profession reclaims authority in doctor-patient relationships. Professions and Professionalism, 6(2). https://doi.org/10.7577/pp.1622

- Lindström, S. (2015). Constructions of professional subjectivity at the fine arts college. Professions & Professionalism, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.7577/pp.869

- Loshin, J. (2010). Secrets revealed: How magicians protect intellectual property without law. In C. A. Corcos (Ed.), Law and magic: A collection of essays (pp. 123-142). Durham, N.C: Carolina Academic Press.

- L’Yi, S., Koh, K., Jo, J., Kim, B., & Seo, J. (2016). CloakingNote: A novel desktop interface for subtle writing using decoy texts. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM Annual Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology Tokyo, Japan – October 16–19, 2016 (pp. 473–481). https://doi.org/10.1145/2984511.2984571

- Nardi, B., Whittaker, S., & Schwarz, H. (2000). It’s not what you know it’s who you know. First Monday, 5(5). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v5i5.741

- Rensink, R. A., & Kuhn, G. (2015). The possibility of a science of magic. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1576. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01576

- Rissanen, O., Palonen, T., & Hakkarainen, K. (2010). Magical expertise: An analysis of Finland’s national magician network. In L. Dirckinck-Holmfeld, V. Hodgson, C. Jones, M. de Laat, D. McConnell, & T. Ryberg (Eds.), Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Net-worked Learning 2010 (pp. 344-352). Aalborg: Aalborg University.

- Rissanen, O., Palonen, T., Pitkänen, P., Kuhn, G., & Hakkarainen, K. (2013). Personal social networks and the cultivation of expertise in magic: An interview study. Vocational Learning, 6, 347-365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-013-9099-z

- Rissanen, O., Pitkänen, P., Juvonen, A., Kuhn, G., & Hakkarainen, K. (2014). Expertise among professional magicians: an interview study. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1484. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01484

- Shirky, C. (2010). Cognitive surplus. New York: Penguin.

- Sirén, M. (2014). Jose Ahonen ja koiravideo – Viraalimarkkinoinnin lyhyt oppimäärä. [Jose Ahonen and the dog video – A brief lesson in viral marketing]. Jokeri, taikuutta taikureille, [Joker, magic for magicians], 78(2), 15-18, Kouvola, Markku Purho Ky.

- Svensson, L. G. (2015). Occupations and professionalism in art and culture. Professions & Professionalism, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.7577/pp.1328

- Williams, H., & McOwan, P. (2014). Magic in the machine: A computational magician’s assistant. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1283. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01283