Olaf Gjerløw Aasland

Healthy Doctors – Sick Medicine 1

Abstract: Doctors are among the healthiest segments of the population in western countries. Nevertheless, they complain strongly of stress and burnout. Their own explanation is deprofessionalisation: The honourable art of doctoring has been replaced by standardised interventions and production lines; professional autonomy has withered. This view is shared by many medical sociologists who have identified a “golden age of medicine,” or “golden age of doctoring,” starting after World War II and declining around 1970.This article looks at some of the central sociological literature on deprofessionalisation, particularly in a perspective of countervailing powers. It also looks into another rise-and-fall model, proposed by the medical profession itself, where the fall in professional power was generated by the notion that there are no more white spots to explore on the map of medicine.Contemporary doctoring is a case of cognitive dissonance, where the traditional doctor role seems incompatible with modern health care.

Keywords: deprofessionalisation; professional autonomy; cognitive dissonance; golden age of doctoring

Global life expectancy is constantly on the rise, and increased from 65.3 years in 1990 to 71.5 years in 2013. Two major contributors are reductions in age standardised death rates for cardiovascular diseases and cancers in high-income regions, and reductions in child deaths from diarrhoea, lower respiratory infections and neonatal causes in low-income countries (Global Burden of Disease [GBD], 2015).

The main causes for this upward trend in global health are improved socioeconomic conditions. The importance of socioeconomic conditions is manifested through the presence of another trend: steadily increasing socioeconomic inequalities in health (Plug et al., 2012). Historically, organised medicine has been instrumental in improving life expectancy, despite for example Illich’s idea of medical imperialism and the iatrogenic effect of doctoring (Illich, 1975) or McKeown’s thesis about the superiority of improved social conditions over public health interventions and medical treatment (Colgrove, 2002). In the political campaigns against increasing socioeconomic inequalities in health, however, organised medicine has been impotent (Plug et al., 2012).

In the quest for better and longer lives the doctors themselves are definitely winners. Over the last 150 years their mortality has decreased from above average (Ogle, 1886) to below (Aasland, Hem, Haldorsen, & Ekeberg, 2011).

From a public health perspective the mortality and morbidity of doctors is of particular interest. Not only do they possess much information about health risks, diseases and available treatments, they also constitute a very homogenous upper socioeconomic group of mostly non-smokers with moderate alcohol habits, little overweight and optimal physical activity, at least in Norway (Rosta & Aasland, 2012). They seldom take sick leave (Rosta, Tellness, & Aasland, 2014), and despite long working hours they are culturally active also outside medicine (Nylenna & Aasland, 2013). As professional group the doctors are among the healthiest. For the purpose of this paper, an interesting question is how the doctors’ health and well-being is associated with the functionality and efficacy of the health care systems in which they work.

There is a strange and unexpected downside to the success story of the healthy doctors. For the last generation or two, doctors in most countries have increasingly been complaining about stress, burnout and other negative aspects of work life. Instead of appreciating and celebrating the constantly improving population health and the growing number of new or improved diagnostic and therapeutic possibilities in medicine, doctors seem to be increasingly discontent. What is going on? Why this paradox with doctors being among the healthiest on the one side and so much suffering from stress and burnout on the other (Aasland et al., 2011; Frank, Biola, & Burnett, 2000; Frank & Segura, 2009; Shanafelt et al., 2012; Statistics Sweden, 2014; Wiskar, 2012)? The doctors themselves almost unanimously explain their discontent with loss of professional autonomy. There is no longer room for “the art of doctoring,” only for standardised interventions and production lines. They are victims of deprofessionalization (Reed & Evans, 1987). The decline in individual autonomy for doctors started already around 1960, with the end of the so-called “golden age of medicine” (Hafferty & Light, 1995). However, during the last two decades there has been a growing interest in the individual doctor’s health and well-being, manifested through a high and increasing prevalence of stress and burnout, often associated with and explained by the perceived loss of professional autonomy (Shanafelt et al., 2012; Wallace, Lemaire, & Ghali, 2009). But the evidence based link between professional autonomy and the doctors’ individual health and well-being remains to be established.

In this article, I will first review some sociological theories on deprofessionalisation, particularly with a view to the medical profession. Then I will present some alternative medical theories, suggested by the doctors themselves, and mention briefly some other trends that may be associated with perceived loss of professional autonomy. Finally, I suggest some possible explanations why today’s doctors are discontent, and to what extent this can be remedied.

Countervailing powers: a useful sociological concept

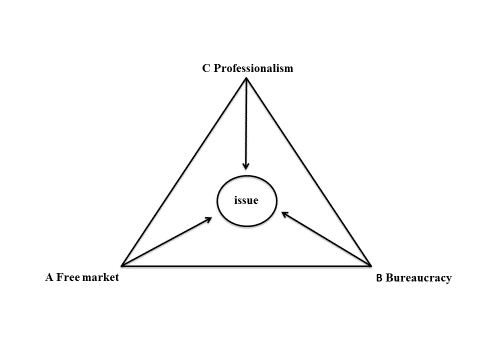

An influential sociological theory of professions is based on the concept of countervailing powers, for instance as described by Hafferty (2003), here illustrated in a vector diagram:

The issue under consideration, the physician-patient relationship for example, would occupy a point somewhere within the confines of this triangle—with three lines or vectors radiating from that point, one to each of the three ideal type nodes.

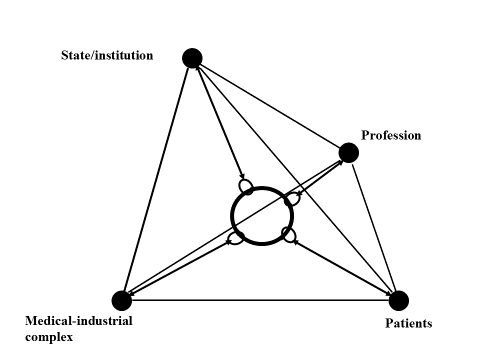

The triangle can be expanded to a tetrahedron (a geometric object with four corners), where the fourth vector is constituted by the patients or their different interests (family, patient-organisations etc.). The four vectors are pulling the ring in the middle, which could represent any of a number of health issues, for example an expensive cure, from their particular corner. In the ideal situation the ring stays in the center of the tetrahedron. In a situation with for example attenuated professional power, the distance between the profession corner and the ring becomes longer, and the other distances respectively shorter.

These models are useful because they identify the main health policy actors and illustrate how their interactions can be seen as a power game.

The sociological literature on professional power in medicine is heavily dominated by the US-tradition, which is probably not incidental. With its absence of universal coverage the US health care system differs from most other western systems with more focus on market and power and patients as individual buyers. Indeed, the growing “patient movement,” as described by Rothman (2001), has by US sociologists also been characterized as “the buyers revolt” (Light, 1997).

The end of the golden age of doctoring?

Eliot Freidson (1923 – 2005) was one of the first US post-war sociologists to discuss the professional dominance of the medical profession, with his two books from 1970 (Freidson 1970a, Freidson 1970b). Ron Miller wrote in a review of Profession of Medicine in Sociological Quarterly:

Given the expanding domain of what is illness (e.g. crime, homosexuality) and the contentions of physicians about their rights as professionals, Freidson wonders aloud whether expertise is becoming a mask for privilege and power. He views the knowledge of medicine as being mostly moral evaluation and custom, only partly scientific (Miller, 1971, p. 129).

In two later articles Freidson identified three major positions in the American sociological discourse on the medical profession (Freidson 1984, Freidson 1985):

-

The corporatization of health care that forces physicians to become salaried employees in large health care organizations (McKinlay & Arches, 1985; McKinlay & Stoeckle, 1987).

-

The loss of the knowledge monopoly. The emerging information society reduces the medical profession’s possibilities for maintaining its knowledge monopoly, which ultimately is its power source (Haug, 1975).

-

Continuing professional dominance, Freidson’s own position. The dominance is still strong, but takes on new forms, particularly through a strategic stratification into an administrative elite, a knowledge elite, and ordinary rank-and-file practitioners (Freidson, 1984).

In his last book Professionalism: the third logic. On the practice of knowledge, Freidson (2001) is no longer so sure whether professions, including the doctors, will survive the increasing pressure from market and bureaucracy. In his concluding chapter, The soul of professionalism, he nearly advocates “unchecked autonomy”: “ … professional ethics must claim an independence from patron, state and public that is analogous to what is claimed by a religious congregation” (p. 221). One of his sharpest critics, Frederic Hafferty (2003), also professor of sociology, characterized this position as an invitation to professional anarchy. Hafferty does not believe in individual professional autonomy: “Organized medicine has not chosen to be committed to meaningful peer- and self-review and reflection, and until it does, the battle for medicine’s ‘soul’ is being left to just two players: the free market and managerialism.”

In 2002, McKinlay and Marceau published “The end of the golden age of doctoring.” They view the future of medicine in the US as rather gloomy and identify six extrinsic and two intrinsic interrelated reasons for the decline of the golden age of doctoring:

Major extrinsic factors (generally outside the control of the profession):

-

the changing nature of the state and loss of its partisan support for doctoring

-

the bureaucratization (corporatization) of doctoring

-

the emerging competitive threat from other health care workers

-

the consequences of globalization and the information revolution

-

the epidemiologic transition and changes in the public conception of the body

-

changes in the doctor-patient relationship and the erosion of patient trust

Major intrinsic factors (can be controlled by the profession):

-

the weakening of physicians’ labour market position through oversupply;

-

the fragmentation or weakening of the physicians’ union (AMA).

They hold that a future sociology of the professions can no longer overlook now pervasive macrostructural influences on provider behaviour (corporate dominance). Until these influences are appropriately recognized and incorporated in social analyses, most policies designed to restore the professional ideal have little chance of success.

In 2003 Light wrote a more optimistic paper. He suggests a shift in focus from professional autonomy to professional accountability, and describes a new professionalism that will provide a healthy future for the medical and other health professions. This new professionalism “restores the social compact with society and refocuses professionals on serving the needs of people in society. It restores trust and assures patients that doctors are working for them and to high standards” (Light, 2003, para. 72).

McKinlay and Light represent two quite different positions: McKinlay lays almost everything on the workplace or the system, the doctor role remains more or less the same, while Light wants a new type of doctor. Despite certain influences from other health care systems, their positions nevertheless spring from the US tradition with a market based health care without universal coverage.

For many US-doctors the advent of the Affordable Care Act (ACA or “Obamacare”) is perceived as just another nail in the coffin for their professional autonomy, and a threat to future quality of health care (Amerling, 2010). However, Emanuel and Pearson (2012) contend that the ACA on the contrary “has provisions that will mitigate the long-standing concern that payers determine what physicians can and cannot do and will instead enhance the role and authority of the medical profession” (p. 367). But this will not happen on its own. In order to keep or enhance their autonomy, doctors must redesign their delivery systems into “models with cost and quality indicators that they are willing to be accountable for” (p. 368).

Comparative perspectives: Eliot Krause and Death of the Guilds

An interesting exception from the US sociologist hegemony was offered by Eliot Krause. In his book Death of the Guilds: Professions, States, and the Advance of Capitalism, 1930 to the Present (Krause, 1996) he takes his detailed and well researched examples from four professions: medicine, law, engineering and the professoriate, and five countries: Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and the United States. He sees the professions as the last remnants of medieval guilds, where four elements, were crucial to guild power: control over who could become and remain a craftsman, control over the workplace (the means and pace of production), control over the market (having a monopoly of the product and being able to set its price), and control over the state, at least insofar as being able to wring from the state its gatekeeping and market powers. Krause finds that the decline in professional autonomy occurs in most of the professions and countries under study. The reason for the decline is that capitalism and the state “have finally caught up with the last guilds” (Krause, 1996, p. 280). The market and the state, each with its own distinct, if overlapping, interests become the two most likely antagonists that members of a profession must hold at bay if they are to control their destinies.

There is an interesting “outlier” in Krause’s matrix, the situation for medical professionals in Italy. He describes how the political parties in Italy exercise such extensive control that no profession can function independent of political party decision making—called partitocrazia. The medical profession developed in close connection with the state, with generalists to the left (PCI - Partito Communista Italiano) and specialists to the right (DC - Democrazia Christiana). Subsequent attempts from the state to rationalize the health system and control costs have unified the profession across party borders, and thereby actually increased its power. In Berlusconi’s Italy and after, doctors still seem to retain their professional power, both through “recolonizing” managerial positions, and through coercive isomorphism, the practice of two parallel logics of action: a formal and visible one to respect “external” ceremonies, and an informal one closer to their traditional mode of action (Vicarelli & Pavolini, 2012).

Krause (1988, p. 149) writes tellingly that: “Italy is the graveyard of political and sociological theories, and those of the professions are no exception.” The Italian case tells us that professional power may vary considerably in both time and space, and since there is no real decline in such power in Italy, and possibly other places, that “the golden age of doctoring” perhaps is more of a local US-phenomenon than an international trend.

Strangers at the bedside and failing medical ethics

A different perspective is offered by another American scientist, historian David Rothman, in his book “Strangers at the bedside: A history of how law and bioethics transformed medical decisionmaking” (Rothman, 1991). Starting with Beecher’s documentation of abuses in human experimentation in contemporary clinical research (Beecher, 1966), Rothman writes:

Outsiders to medicine—that is, lawyers, judges, legislators, and academics— penetrated its every nook and cranny, in the process giving medicine an exceptional prominence on the public agenda and making it the subject of popular discourse. This glare of the spotlight transformed medical decision making, shaping not merely the external conditions under which medicine would be practiced (something that the state, through the regulation of licensure, had always done), but the very substance of medical practice—the decisions that physicians made at the bedside.

The change was first manifested and implemented through a new commitment to collective, as against individual, decision making (Rothman, 1991, p. 3).

Rothman describes three aspects of how this collective decision making has developed:

-

Standing committees to ensure that a researcher who would experiment with human subjects was not making a self-serving calculus of risks and benefits.

-

Written documentation was replacing word-of-mouth orders (or pencil notations to be erased later), as in the case of coding a patient DNR (do not resuscitate).

-

Outsiders now framed the normative principles that were to guide the doctor-patient relationship.

Rothman offers several examples of how the medical establishment, and particularly the doctors, bypassed ethical principles or safety controls, one of the more famous being the Thalidomide disaster, where thousands of babies were born crippled because their mothers had used the recommended but not sufficiently tested drug Thalidomide for morning sickness. Rothman himself does not use the expression “golden age.” On the contrary, he sees much of the post-war development in medicine as an uncritical extension of the military wartime ethics and logic where the end always justifies the means into post war civil society.

The Rise and Fall of Modern Medicine

Apocalyptic descriptions of medicine are not only reserved for sociologists. In 1999, the English doctor and columnist James Le Fanu wrote a “bestseller” with this title. His point of departure is similar to the paradoxes described at the beginning of this article:

Yet despite this exemplary vindication of the power of science, the future of medicine is dark and uncertain, its practitioners no longer sustained by the sense of optimism of earlier decades. Meanwhile the public are encouraged quite wrongly to believe their everyday lives are full of hidden hazards and the escalating costs of medical care undermine the ideal of a universal and equitable treatment for all (The rise and fall of modern medicine, n.d., para. 2).

The driving force in Le Fanu’s account is a popularized but very professional description of medical progress. From his home-grown list of 36 historical events in medicine, he picks “twelve definitive moments of modern medicine,” and devotes one whole chapter to each moment:

-

Penicillin (1949)

-

Cortisone (1949)

-

Smoking identified as the cause of lung cancer (1950)

-

The Copenhagen polio epidemic with the birth of intensive care (1952)

-

Chlorpromazine in the treatment of schizophrenia (1952)

-

Open-heart surgery (1955)

-

Charnley’s hip replacement (1961)

-

Kidney transplantation (1963)

-

Prevention of strokes (1964)

-

Cure for childhood cancer (1971)

-

First test-tube baby (1978)

-

Helicobacter as the cause of peptic ulcer (1984)

He then presents his four-layered paradox: 1) Disillusioned doctors, 2) The worried well, 3) The soaring popularity of alternative medicine and 4) The spiraling costs of health care. Le Fanu contends that, despite the complexity of these paradoxes:

…it is possible to perceive there might also be a single unifying explanation that can readily be seen from the earlier chronology of major events. The crucial factor is the dates, with the massive concentration of important innovations from the 1940s through to the 1970s followed by a marked decline (The rise and fall of modern medicine, n.d., para. 13).

His narrative of “the rise and fall of modern medicine” clearly coincides with “the end of the golden age of doctoring,” as described by several sociologists. Interesting then that the word “deprofessionalisation” or the names of for example Eliot Freidson or John B. McKinlay are not to be found in Le Fanu’s book. His explanation of the decline is purely medical: the incidence of definitive moments in medicine has flattened out—there are no more white spots to explore on the map of human medicine.

Predictably Le Fanu’s book was both praised and criticized, but the market enthusiastically swallowed a fully revised and updated second edition in 2011, where his main position remains unchanged. The editor-in-chief of The Lancet, Richard Horton (2000) reviewed the book. He skilfully dismembers most of Le Fanu’s logic and transforms categorical arguments into ambivalence. Horton does not share Le Fanu’s apocalyptic view on modern medicine, and shows how it still is and always has been on the rise, if you are willing to see medical research as “just as self-serving as any other branch of human inquiry. To claim a special moral purpose for medicine or even a beneficent altruism is simply delusional” (para. 55). Nor does he share his view on how the new medical technology impacted the doctors:

…to make doctors feel that their calling was being transformed into something quite miraculous. And here, according to Le Fanu, was the seed of subsequent decline. For doctors “came to believe their intellectual contribution to be greater than it really was, and that they understood more than they really did” (Horton, 2000, para. 22).

Overwork, undersupport and double medicalization—the doctor as victim

In 2001, the editor in chief of the British Medical Journal (BMJ) Richard Smith wrote an editorial: Why are doctors so unhappy? (Smith, 2001). The ingress was: “There are probably many causes, some of them deep.” Smith’s most obvious cause was the doctors’ experience of being overworked and undersupported, while an example of a deeper cause was the mismatch between what doctors were trained for and what they are required to do. He suggested a “redrafted bogus contract” between doctors and patients, where the main idea is their shared responsibility: “We’re in this together.”

Smith describes a gap between what the doctors as medical professionals should and can do, and what they are expected to do from patients, politicians and society. In this gap, we find some excellent soil for different variants of medicalization where non-medical, often complex problems are re-dressed as medical. Medicalization can go both ways, either that doctors claim jurisdiction over non-medical issues, eloquently described by Illich (1975) as social iatrogenesis, or that non-doctors redefine unusual social behaviour, for instance criminal behaviour, as medical conditions, sometimes even with a promise of cure. There are always some doctors who are flattered by such bogus power and become useful idiots, thereby nurturing the myth of the omnipotent doctor (Aasland, 1992). Another observation is that while Le Fanu (1999) alludes to the doctors as innocent victims of a derailed health care system, Smith (2001) deals with the dysfunctional communication between the doctors and the system.

Sick doctors?

The former BMJ editor Richard Smith’s intervention gave strong momentum to an already nascent trend of doctors’ preoccupation with their own health and work life. Several health programs for “sick doctors,” and groups and networks for those who do research on or help sick doctors have recently been established, and there are regular meetings both internationally and on a European level, characteristically organized through or in collaboration with the medical associations. The focus has gradually shifted from how to help and deal with “impaired” or “disruptive” physicians on an individual level into how modern health care exploits, demotivates and debilitates all the doctors. Burnout is the new plague. A competent group of researchers at the Mayo clinic have documented that almost every other American doctor “show at least one 1 symptom of burnout” (Shanafelt et al., 2012), which in the US media is presented as The Widespread Problem of Doctor Burnout (Chen, 2012):

The study casts a grim light on what it is like to practice medicine in the current health care system. A significant proportion of doctors feel trapped, thwarted by the limited time they are allowed to spend with patients, stymied by the ever-changing rules set by insurers and other payers on what they can prescribe or offer as treatment and frustrated by the fact that any gains in efficiency offered by electronic medical records are so soon offset by numerous, newly devised administrative tasks that must also be completed on the computer (para. 11).

A comprehensive literature review by Wallace et al. (2009) on “Physician wellness: a missing quality indicator” also paints a rather pessimistic picture of the doctors health. Despite its title, the paper does not review positive aspects of doctors’ health, only negative. The main message is that doctors have an exceptionally high risk of stress and burnout, and a very low ability to seek help when necessary, which may affect their patients negatively. The authors’ conclusion is:

Assessment of physician wellness as an indicator of an organisation’s quality of health care is only the first step. Increased awareness of the importance of physician wellness, both individually and organisationally, is needed by physicians, their patients, and their employers…. If these groups do not recognise the crucial importance of physician wellness, there is little reason to expect that physicians and their employers will invest in taking better care of physicians, or that the public will support and appreciate such efforts. Ultimately, individual physicians will personally benefit from taking better care of themselves (Wallace et al., 2009, p. 1719).

Unfortunately, the paper does not indicate what physicians, their patients and their employers (“these groups”) can do, other than recognising the crucial importance of physician wellness. And ultimately it is really up to the doctors themselves to take better care of their own health (which, as already described, is excellent).

Other trends

Some other trends may also have a bearing on the doctors perceived loss of status and autonomy. One is demographic change: the almost explosive increase in doctor density and the growing proportion of female doctors. Since 1970 the number of inhabitants per doctor in Norway has decreased from 743 to 214, and the fraction of female doctors increased from 12 to 47 per cent. Doctors are simply not so special anymore. In 2004, the then president of the Royal College of Physicians in London, Dame Carol Black, said controversially: “We are feminising medicine. It has been a profession dominated by white males. What are we going to have to do to ensure it retains its influence?” (Women docs, 2004, para. 5). These facts could in themselves explain why especially the male doctors who have experienced “the golden age” experience a loss of status and autonomy.

Doctors are by far are the most cost generating professionals in health care, and it follows that economic conjunctures will have a bearing on their professional autonomy (Kälble, 2005). One contributing cause to the perceived end of the golden age of doctoring and loss of professional autonomy could therefore very well be the global economic crisis that hit in the fall of 1973 when a long-standing high post-war conjuncture fell abruptly. In the US, the economic crisis also coincided with the introduction of Medicare and Medicaid, which for many doctors was in itself perceived as a threat to their professional autonomy.

Two other trends that also gained momentum in the 1970’s are the academization of other health professions, for instance nurses who became nurse practitioners and challenged the primary health care doctors’ autonomy (Flanagan, 1998), and the proliferation of new health professions operating partly inside the original doctor jurisdictions, for instance radiographers or psychologists. In modern medicine doctors are no longer unique and indispensable. In Norway there are presently 29 different authorized health professions, all regulated through the same act, The Health Personnel Act, from 2001.

Synthesis

Based on the notion that the doctors themselves tend to ascribe their discontent to a perceived loss of professional autonomy, I have reviewed some of the sociological literature on professional autonomy and deprofessionalisation in a historic, and to a certain extent comparative, perspective. I have also included some viewpoints from representatives of the medical profession itself.

A theme that appears repeatedly in both the sociological and medical accounts is the gap between ideals or expectations and reality. McKinlay and Marceau (2002) show how the end of the golden age of doctoring with its partisan loss of support from the state, increased bureaucratization, competition from other health care professionals and information revolution is not compatible with the traditional autonomous doctor role: “Until these influences are appropriately recognized and incorporated in social analyses, most policies designed to restore the professional ideal have little chance of success” (p. 379). Le Fanu suggests that the reason for the downfall was that the doctors “came to believe their intellectual contribution to be greater than it really was, and that they understood more than they really did.” (Le Fanu, 1990, as cited in Horton, 2000, para. 22). Light (2003) shows us a new quality-value-and-trust doctor, who is very “politically correct”, but will such a doctor ever materialize? According to Emanuel (2012) the doctor must redesign his delivery systems into models with cost and quality indicators that he is willing to be accountable for, which again means more use of electronic health records with decision support. And Richard Smith’s (2001) seven points address directly the gap between what doctors can do and what they are expected to do.

I believe that some of the discontent and burnout can be explained by a conflict between the ideal traditional, trusted, reflexive and Hippocratic doctor role of yesterday and the contemporary doctor who only sees fragments of patients and patient lives. General practitioner and writer William Carlos Williams (1883-1963) needed to listen to all the patient’s words—to him they became poetry (Williams, 1967). For the modern general practitioner it is only a matter of seconds before the patient’s “poem” is interrupted by the doctor’s first question (Schei, 2015).

We can look at this as a case of cognitive dissonance, a phrase coined by the American social psychologist Leon Festinger (1919-1989) in the 1950s. “In the course of our lives we have all accumulated a large number of expectations about what things go together and what things do not. When such an expectation is not fulfilled, dissonance occurs” (Festinger, 1962, p. 94). Cognitive dissonance may also explain why stress and burnout seem more prevalent in the US, where professional ethics and values of medicine are more challenged due to a market based health care system that excludes some of the sickest patients. Further, since Norway is a country with universal, free health care and also shorter working hours for doctors (Rosta & Aasland, 2014), it may explain why Norwegian doctors report high and increasing job- and life satisfaction (Nylenna, Gulbrandsen, Førde, & Aasland, 2005) and much lower burnout rates (Langballe et al., 2011). Another place for possible doctor role conflicts is the work-home interface (Langballe et al., 2011). Different from earlier generations contemporary professionals are also expected to spend time actively in their private social networks.

If we accept the idea of cognitive dissonance between the traditional doctor role and the very limited possibilities for a doctor to live it out, there are really only two alternatives for cure, revision of the traditional doctor role or revision of existing health care systems. None seems very likely, but a combination of Wallace et al.’s (2009) suggestion of using physician wellness as an indicator of an organisation’s quality of health care and Light’s (2003) new superdoctor where autonomy is replaced with accountability should at least be explored.

Epilogue

Doctors are devoted, “hand-picked” individuals, usually in excellent health, but with a superannuated professional heritage, which too readily puts them into the victim’s role as “cognitive dissonants.” Some settings are less malicious than others, but the situation does not appear to be sustainable. A mismatch between the traditional doctor role and the comprehensive and professional requirements and challenges of modern medicine generates increasing discontent and frustration. The creation of a new doctor role, starting with basic training of doctors as leaders and active team members more than altruistic individualists is not only necessary, it is long overdue (Frenk et al., 2010).

References

- Amerling, R. (2010). ObamaCare: The threat to physician autonomy. Retrieved from: http://www.aapsonline.org/newsoftheday/008 61

- Aasland, O. G. (1992). Legen som juridisk nøtteknekker. [The doctor as legal nut-cracker]. In A. Syse & A. Kjønstad (Eds.), Helseprioriteringer og pasientrettigheter (pp. 69-93). Oslo: Ad Notam/Gyldendal.

- Aasland, O. G., Hem, E., Haldorsen, T., & Ekeberg, Ø. (2011). Mortality among Norwegian doctors 1960-2000. BMC Public Health, 11, 173. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-173

- Beecher, H. (1966). Ethics and clinical research. New England Journal of Medicine, 24(274), 1354-1360. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM196606162742405

- Chen, P. (2012, August 23). The widespread problem of doctor burnout. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/08/23/the-widespread-problem-of-doctor-burnout/?_r=1

- Colgrove, J. (2002). The McKeown thesis: a historical controversy and its enduring influence. American Journal of Public Health, 92(5), 725-729.

- Emanuel, E. J., & Pearson, S. D. (2012). Physician autonomy and health care reform. Journal of the American Medical Association, 307(4), 367-368. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.19

- Festinger, L. (1962). Cognitive dissonance. Scientific American, 207, 93-102.

- Flanagan, L. (1998). Nurse practitioners: growing competition for family physicians? Family Practice Management, 5(9), 34-43. http://www.aafp.org/fpm/1998/1000/p34.html

- Frank, E., Biola, H., & Burnett, C. A. (2000). Mortality rates and causes among U.S. physicians. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 19(3), 155-159. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797%2800%2900201-4

- Frank, E., & Segura, C. (2009). Health practices of Canadian physicians. Canadian Family Physician, 55, 810-811.

- Freidson, E. (1970a). Profession of medicine: a study of the sociology of applied knowledge. New York: Harper & Row.

- Freidson, E. (1970b). Professional dominance: the social structure of medical care. New York: Atherton Press.

- Freidson, E. (1984). The changing nature of professional control. Annual Review of Sociology, 10, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.10.080184.000245

- Freidson, E. (1985). The reorganization of the medical profession. Medical Care Review, 42, 11-35. https://doi.org/10.1177/107755878504200103

- Freidson, E. (2001). Professionalism: the third logic. On the practice of knowledge. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Frenk, J., Chen, L., Zulfi, A. B., Cohen, J., Crisp, N., Evans, T., Fineberg, H., Garcia, P., Ke, Y., Kelley, P., Kistnasamy, B., Meleis, A., Naylor, D., Pablos-Mendez, A., Reddy, S., Scrimshaw, S., Sepulveda, J., Serwadda, D., & Zurayk, H. (2010). Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. The Lancet, 376, 1923-1958. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736%2810%2961854-5

- Global Burden of Disease. (2015). Global, regional, and national age–sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet, 385(9963), 117-171. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2

- Hafferty, F. W., & Light, D. W. (1995). Professional dynamics and the changing nature of medical work. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 35(Special issue), 132-153.

- Hafferty, F. W. (2003). . Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 28(1), 133-138. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-28-1-133

- Haug, M. (1975). The deprofessionalization of everyone? Sociological Focus, 8, 197-213. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380237.1975.10570899

- Horton, R. (2000). How sick is modern medicine? Review of The Rise and Fall of Modern Medicine by James Le Fanu. New York Review of Books, 2. Retrieved from http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2000/nov/02/how-sick-is-modern-medicine/

- Illich, I. (1975). Medical nemesis. The expropriation of health. London: Calder & Boyars.

- Kälble, K. (2005). Between professional autonomy and economic orientation — The medical profession in a changing health care system. GMS Psychosocial Medicine, 2. http://www.egms.de/static/en/journals/psm/2005-2/psm000010.shtml

- Krause, E. A. (1988). Doctors, partitocrazia, and the Italian state. The Milbank Quarterly, 66(2), 148-166. https://doi.org/10.2307/3349920

- Krause, E. A. (1996). Death of the guilds: Professions, states, and the advance of capitalism, 1930 to the present. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Langballe, E. M., Innstrand, S. T., Aasland, O. G., & Falkum, E. (2011). The predicttive value of individual factors, work-related factors, and work–home interaction on burnout in female and male physicians: a longitudinal study,. Stress and Health, 27(1), 73-87. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1321

- Le Fanu, J. (1999). The rise and fall of modern medicine. New York: Little Brown.

- Light, D. W. (1997). The restructuring of the American health care system. In T. J. Litman & L. S. Robbins (Eds.), Health Politics and Policy (pp. 46-63). Albany, NY: Delmar.

- Light, D. W. (2003). Towards a new professionalism in medicine: Quality, value and trust. The Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association, 13-14. http://tidsskriftet.no/article/843776

- McKinlay, J. B., & Arches, J. (1985). Towards the proletarianization of physicians. International Journal of Health Services, 15(2), 161-195. https://doi.org/10.2190/JBMN-C0W6-9WFQ-Q5A6

- McKinlay, J. B., & Stoeckle, J. (1987). Corporatization and the social transformation of doctoring. Sosiaalääketieteellinen Aikakauslehti, 24, 73-84.

- McKinlay, J. B., & Marceau, L. (2002). The end of the golden age of doctoring. International Journal of Health Services, 32(2), 379-416. https://doi.org/10.2190/JL1D-21BG-PK2N-J0KD

- Miller, R. (1971). Review of Freidson’s Profession of Medicine. The Sociological Quarterly 12 [1], 128-30.

- Nylenna, M., Gulbrandsen, P., Førde, R., & Aasland, O. G. (2005). Unhappy doctors? A longitudinal study of life and job satisfaction among Norwegian doctors 1994 – 2002. BMC Health Services Research, 5, 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-5-44

- Nylenna, M., & Aasland, O. G. (2013). Cultural and musical activity among Norwegian doctors. Tidsskrift for den Norske Legeforening, 133(12/13). https://doi.org/10.4045/tidsskr.12.1518

- Ogle, W. (1886). Statistics of mortality in the medical profession. Medico-Chirurgical Transactions, 69,, 218-237.

- Plug, I., Hoffman, R., Artnik, B., Bopp, M., Borrell, C., Costa, G., Deboosere, P., Esnaola, S., Kalediene, R., Leinsalu, M., Lundberg, O., Martikainen, P., Regidor, E., Rychtarikova, J., Strand, B. H., Wojtyniak, B., & Mackenbach, J. (2012). Socioeconomic inequalities in mortality from conditions amenable to medical interventions: do they reflect inequalities in access or quality of health care? BMC Public Health, 12, 346. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-346

- Reed, R. R., & Evans, D. (1987). The deprofessionalization of medicine. Causes, effects and responses. Journal of the American Medical Association, 258(22), 3279-82. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1987.03400220079041

- Rosta, J., & Aasland, O. G. (2013). Changes in Alcohol Drinking Patterns and Their Consequences among Norwegian Doctors from 2000 to 2010: A Longitudinal Study Based on National Samples. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 48(1), 99-106. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/ags084

- Rosta, J., Tellnes., G., & Aasland, O. G. (2014). Differences in sickness absence Between self-employed and employed doctors: a cross-sectional study on national sample of Norwegian doctors in 2010. BMC Health Services Research, 14, 199. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-199

- Rosta, J., & Aasland, O. G. (2014). BMJ Open (Vol. 4). Weekly working hours for Norwegian hospital doctors since 1994 with special attention to postgraduate training, work–home balance and the European Working Time Directive: a panel study., e005704. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005704

- Rothman, D. J. (1991). Strangers at the bedside: A history of how law and bioethics transformed medical decision making. New York: Basic Books.

- Rothman, D. J. (2001). The origins and consequences of patient autonomy: A 25-Year Retrospective. Health Care Analysis, 9(3), 255-264. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012937429109

- Schei, E. (2015). Lytt. Legerolle og kommunikasjon (Listen. Doctor’s role and communication). Oslo: Fagbokforlaget.

- Shanafelt, T. D., Boone, S., Tan, L., Dyrbye, L. N., Sotile, W., Satele, D., West, C., Sloan, J., & Oreskovich, M. R. (2012). Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172(18), 1377-1385. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199

- Smith, R. (2001). Why are doctors so unhappy? BMJ, 322, 1074-1075. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1073

- Statistics Sweden. (2014). Yrke och dødlighet 2008 -2012 [Mortality by occupation in Sweden 2008-2012]. Report 2014 (3). Retrieved from http://www.scb.se/Statistik/_Publikationer/BE0701_2014A01_BR_BE51BR1403.pdf%20

- The rise and fall of modern medicine. (n.d.) Retrieved from: http://www.jameslefanu.com/books

- Vicarelli, G., & Pavolini, E. (2012, November). A new professionalism for Italian doctors? The hybridisation of doctors and managers in the Italian NHS, Paper presented at ISA RC 52 Conference, Ipswich.

- Wallace, J. E., Lemaire, J. B., & Ghali, W. A. (2009). Physician wellness: a missing quality indicator. The Lancet, 374(9702), 1714-1721. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736%2809%2961424-0

- Williams, W. C. (1967). The practice. In W. C. Williams (Ed.), The autobiography of William Carlos Williams (pp. 356-362). New York: New Directions Paperbook.

- Wiskar, K. (2012). Physician health: A review of lifestyle behaviors and preventive health care among physicians. BCMJ, 54(8), 419-423.

- Women docs “weakening” medicine. (2004, August 2). BBC News. Retrieved from http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/3527184.stm