Special issue: “Darkness matters”

Guest Editors

Camilla Eline Andersen, camilla.andersen@inn.no

Faculty of Education and Natural Science, Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences

Teija Rantala, teija.rantala@helsinki.fi

Faculty of Arts, University of Helsinki

Pauliina Rautio, pauliina.rautio@oulu.fi

Faculty of Education, University of Oulu

NOVEMBERY FOREST

“Our fantastic civilization has fallen out of touch with many aspects of nature, and with none more completely that with the night. Primitive folk, gathered at a cave mouth round a fire, do not fear night; they fear, rather, the energies and creatures to whom night gives power; we of the age of the machines, having delivered ourselves of nocturnal enemies, now have a dislike of night itself. With lights and ever more lights, we drive the holiness and beauty of night back to the forests…”

“By day, space is one with the earth and with man – it is his sun that is shining, his clouds that are floating past; at night, the space is his no more…”

-Henry Beston: The Outermost House (2003, 165, 173)

Pimeyden metodologiat

This special issue is based on an experimental weekend workshop: “Methodologies of Darkness” held around the darkest time of the year, the end of November, in 2015 in Nokia, Finland. For this event scholars from a variety of disciplines, however all connected to education, were gathered to engage with darkness in a forest without knowing what this might produce or create. We were gathered to re-educate ourselves and to disrupt methodological habits that we might perform, that perform us, and that perform educational research. Further, we deliberately wanted to unsettle notions of methodology as a process where the eyes have signified what Haraway writes of as a ‘perverse capacity’ that has distanced the knowing subject from everything around in an ‘interest of unfettered power’ (2002, p. 677). Finally, yet importantly, we were gathered to collaboratively experiment with ways of knowing and sensing in the dark.

As researchers of the world we do not see ourselves as separated from various habitual research practices in educational research that we find problematic or poor, yet this recognition of habitual performances does not solely overwhelm us. Instead, we think of it as a productive and creative force in relation to research methodologies in the educational landscape. It produces creativity; a becoming-creative. Hence, to initiate an unsettling of methodology, the promoters (three of the participants) of the workshop suggested an engagement with the potentially unobvious: darkness. That is to collectively submerge ourselves with darkness as a co-productive force in changing our habitual ‘onto-episte-methodological practices’ (Koro-Ljungberg, 2016, p. 1) where as Haraway suggests, the eye has signified a deviant capacity. Our objective was to unlearn oculocentrism and anthropocentrism in our practices of doing research - to unsettle the hegemony of the ‘eye’ and the ‘human’. We think we got somewhere, but perhaps not very far at all - the eyes of the human are still very present in this issue. We invite the reader to evaluate and critically address how well we succeeded. The journey of unlearning continues for us.

Eight scholars met in a house in Nokia, Finland, in November 2015. A house within walking distance to a forest where we had planned to engage with/in, during the night. A key question guided our experimentation: What will happen to our understanding of qualitative methodologies, to us, theories, senses, and to our material connections in a dark Atumnforest? All having been troubled by and/or hopeful of the ontological turn and the push towards performing research differently, especially within qualitative methodologies, we were eager to collectively practice thinking-doing in a dark forest where losing control through lessening the significance of the eye was considered productive - at least in comparison with our own earlier works.

We wished to create new research practices for ourselves, that in a larger sense could do justice to “what is” and work more actively with “what might be”. Further, we encountered the, perhaps odd, prospect of thinking about qualitative methodologies with trees, moss, forest animals, and wet grass - in relation to darkness. With Deleuze (1995) we were gathered to ‘precipitate’ methodological events in a dark forest that might ‘elude control’ and most importantly ‘engender new space-times’ (p. 176). Another important underlying assumption for our experimental workshop was that methodology and politics are inseparable, and further that experimentation with darkness might turn the common space of research methodology into smooth and virtual time-spaces where events are privileged rather than formed and perceived things (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987).

During the prelude to the workshop a Finnish translation of methodologies of darkness was circulated through email; pimeyden metodologiat. This concept seemed to energize our curiosity for what a dark Autumn forest might do to qualitative methodologies: What might darkness do to our notions of research methodology? What might our new research methodologies be like? Darkness was a phenomenon none of us had engaged extensively with before, although we realized it is an ancient construct as well as a source of creativity and inspiration. We had not collectively discussed what darkness (and light) might do to our notions of research methodology before meeting up. We were nevertheless all curious, and this curiosity seemed to help us overcome the more rational questions and thoughts that habitually seem to be produced when a phenomenon we “know” so well, like methodology, is connected to a milieu or territory that we have never worked with as a methodological matter.

Prior to the event the scholars who had signed up for the workshop, were asked to read three texts: The Abyss: A novel (Yourcenar, 1968), Night and Shadows (Macauley, 2009) and Seeing Dark Things. The Philosophy of Shadows (Aranyosi, 2008). The participants were also asked to prepare and lead a forest activity, no time or space boundaries given. There were no further instructions or planning, except to remember flashlights, warm boots and warm outdoor clothes. Hence, our workshop followed Gilles Deleuze’s idea of experiment as the way to approach scientific questions and phenomena: “Never interpret; experience, experiment” (Deleuze 1995, p. 87). Rather than thinking and imagining darkness, we set out to experience it for ourselves by arranging an evening in a dark forest, with planned, semi-planned and spontaneous experiments to help us think about methodologies, literally in the dark.

The authors of this special issue comprise most of the people from the weekend workshop as well as a few who were invited but could not make it - thus exploring as if ‘in the dark’ the question of what darkness does to research methodology. The issue is made up of what emerged as a consequence of us, as a collective, actively morphing with darkness before, during and after the workshop. In addition, the form of the special issue seeks resonance with the forest engagements; hence, the issue will present emerging compositions of written, visual, and audio reports of these engagements. The objective of the special issue, based on the experimental workshop, is to reconceptualise existing ways of doing educational research by deliberately inducing a concrete challenge in our research activities: darkness, or a much-hindered sense of sight/light. With darkness, we aimed at crafting research practices that not only undo binaries but confuse, scramble and even frighten our binary-seeking minds. And then paying attention to the affects that this created. It is this, that in various ways, is presented as thresholds without clarity. To help a reader follow our experimenting process more easily we will now say something more about what happened in the dark forest and in the following process.

In the Forest

As explained, invited participants were asked to prepare an exercise beforehand that would be brought to the dark Novembery forest. These were introduced during the late evening darkness event when we had been walking for a while with and without flashlights on, had experimented with sounds and found objects in an outdoor amphitheater that we stumbled over, and had found an area in the forest that we collectively agreed on to engage with/in. There was no pre-decided order of the exercises, and none of us knew what others had brought. Neither was there any time schedule. The duration of each exercise emerged with the doing and experimenting.

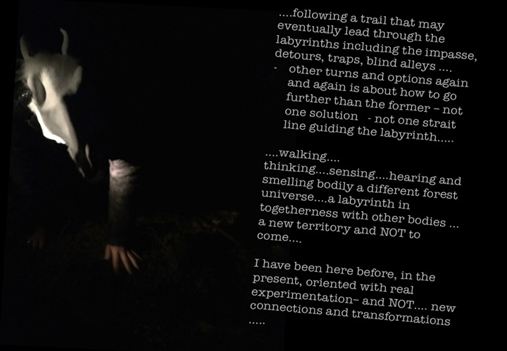

The activities were not unlike those some early childhood educators who bring children to forests might plan. In the process of unlearning and relearning our research practices, we took each other to the forest in a way that we know children are typically taken. The activities we had prepared for each other included diverse multisensory ways of engaging with darkness (and sometimes light) and the forest. For instance, we were all asked to choose something from where we were sitting/standing amid trees, moss, ling, branches, smells, silence, darkness, wet organic materials etc. We were further asked to name this something, to bodily get to know it and finally to celebrate it. This was not collectively shared afterwards. A second example is that we were all asked to move in three different experimental ways with/in the forest. A third example is a sudden becoming-horse-like pop-up happening (see photo below). One of the participants surprisingly put on a horsehead and moved carefully, quiet and slowly with/in the forest for a while.

A fourth example is an exercise where we were asked to experiment with our mobile-cameras in the dark forest (see three photos below). A silent experimentation with darkness and light and branches and lichen and decaying wood and distance and more emerged.

Immediate discussion and sharing followed the darkness event. Gathered around a table inside the house we talked about what had happened to each of us and to our thinking. What had been produced and what might be creative in terms of research methodologies? From these initial articulations, presented in a stream of words below, a direction and a form for a special issue began to take form.

Rather than hiding the context, darkness produces a heightened presence/intensity of it (the forest, us in the forest). The context appears to exist before us as the individuals in it: the context swallows and envelops us, thus forming as if a negative image of the usual research situation where individuals shine and stand out. Without seeing properly, other senses and imagination begin to compensate and become heightened. Rather than seeing-identifying, we are seeing-imagining. Rather than aiming to produce knowledge through (experience of) signification we are immersed in the sounds, the smells, the movements (of trees, air, moss, animals, rain) in the production of the context itself. The ways in which ‘knowledge’ is produced (what knowledge is to begin with) become to rely on these stand-ins for sight/light. It is hard to let go of the pressure to recognize, to give meaning and to define. And we don’t wholly let go either – recognizing just alters its form. We notice that we slow down physically (heart rate, pace of walking, breathing) and seek refuge in anything we can grab onto, lean against or sit on and become alerted somatically. All of our experiments are subtle and aware, and serious if not gloomy or even sinister, our voices low and movements deliberate. Methodology of darkness appears as if contrasting methodologies are at work in light. But not by forming a polar opposite, rather darkness becomes about that which is missing: light and seeing, but generating these as wholly different experiences. Light is gradations of darkness.

The discussions and sharing continued the day after and we talked in more detail about how to create a special issue from the “Methodologies of Darkness” experimental weekend workshop. Elements of the process towards a special issue is what we aim to present below.

Writing ‘in the dark’

Deleuze and Guattari (1987) insist that writing has to do with ‘mapping, even realms yet to come’ (p. 5). With this in mind, with our collective bodily knowledge of what writing might do and with our interest in the new, we decided to create a special issue as an active way of continuing to elude control and engender new time-spaces in relation to methodologies in educational research. We planned that each of us were to create something; a piece, that would be a continuation of the production of lesser blocked ‘arrangements of desire’ (Marks, 1998, p. 118) in relation to methodologies. This we hoped could fuel the always-already process of unsettling methodology as we know it. Further, to challenge the common article format in most journals we decided to create a single piece instead of separate pieces or articles. This larger piece should consist of collectively created smaller pieces. We agreed on a few guidelines before the workshop ended:

Composing is done with self-induced blindness (not entirely seeing what others are writing) and as a negation of a special issue: what is usually highlighted is partially omitted; and what is usually not seen/done we highlight, including but not limited to:

- Writing without seeing what others write

- Writing a single piece rather than separate articles

- Black page and white text

- Some parts in audio (cannot be read as text but has to be listened to)

- Some passages can be in the authors’ (non-English) native languages

As a place to revisit the darkness “Methodologies of Darkness” experimental weekend event while writing/creating, we created a shared Dropbox folder where each participant could upload photos, sounds and videos produced during the workshop. Hence, all of us had access to all the materials produced while working more separately (and not). However, to ensure a more collective process for each piece an elaborate scheme for writing was set up. This scheme formed a constellation of interwoven loops that formed an ongoing chain: everyone was instructed to create an initial piece (of text, sound, images, anything) and send a part of this as a short provocation to a named fellow author (without sending the entire piece). For example, we could send forward the last two written sentences of our piece, or a figure, a quotation, a sound, a number, an image; anything. Each of us would, after receiving a provocation, continue to create a full piece with this little extra spark in the darkness. The full pieces were ultimately sent to us as the editors. We then uploaded the “full” pieces into the shared Dropbox folder leaving the name of the creators out. Then we began to work with how to create an issue that would reflect and convey the idea of a dark forest. Yet something that could be presented in a scholarly journal.

A few of the initial experimenters, both those who were present in the dark forest and those who contributed as if ‘in the dark’ and hence absent-present in the Novembery night, met after three months at a conference to work collectively with what each had composed, and to specifically share what had happened after the dark forest workshop, during and after the writing/creating processes. Practices, ideas and theories were shared. We talked about how we had worked with our pieces, and what this had done to us. About what had happened when a provocative sparkle was received. About how it was to create a piece when not having been in the forest. We discussed philosophical concepts and theories that might help us write something about the whole event and what it might do to our future research practices. The special issue editors, again took over and continued these discussions through Skype-meetings and emails. We aimed at reassembling, composing and working with the pieces in a way that we could create a complexly interwoven yet coherent special issue. In a form which would still resonate with a night in a dark, rainy forest.

Here are a few initial provocations:

Differences:

being in the in-betweenness

of major-scientific-language and becoming-minor-language

as politics

might be that of hinging on to the production of differences

love duration through ‘philosophical intuition’ (Grosz, 2005)

strive to become pregnant with other realities

Every author understood the complicated and multifaceted instructions for writing, differently. First, this caused frustration and confusion, which after a while turned into delight through the realization that if the plan had unfolded perfectly it would have diminished the creative diversity of writing. Furthermore, and in retrospect, confusions and misunderstandings reflected perfectly the idea of writing and thinking in the dark - when clarity is something you imagine, each a little differently. Despite the darkness of the singular productions, sharing the event, senses of the dark forest and the pieces in the processes with one another made the scrambled materials turn into a collective special issue. These pieces share the sparks from the dark forest.

The process of the experimentation as well as writing about it has been layered and segmented in so many ways – both deliberately and accidentally - hence the notion of authorship or perhaps ownership remains dim to say the least. However, as we came closer to publishing the special issue, we decided to create two versions of the issue. One with this editorial and all the pieces put together as one larger piece, and where we all are named as authors. And another version where each piece has an author. This is our way to work with and against publishing systems and to support those of us early in our academic careers.

The challenge has not only been in experimenting and thinking ‘in the dark’ but also attempting to convey multiplicity in the spacetimematterings (Barad, 2007) we had engaged with; to make the reader sense the dark and wintery Finnish forest and the sensations the authors experienced that night. We hope that through these pieces and productions, and their leakages and reproductions, the reader can sense the darkness that enabled us to enter and produce from within it. This piece/publication reaches out to the (s)pace known and unknown, to the way of being, experiencing and expressing the ‘undeniable darkness’ which we understood ourselves to inhabit, but which allows us let go of ‘known’ strategies and create ways of experimenting with the smooth and striated (s)paces of the darkness...

This issue has three interwoven and iterative, non-linear sections which give the reader a choice of freely jumping from one section to another. This said, the issue has been organized with the following patterns and intentions in mind. Firstly, the experiments and the works generated from them are introduced to stress the experimental nature of this work and the ethics involved in experimental research. This is entitled “Novembery forest”. Secondly, collectively made works between two participants are presented to function as thresholds to the experiment. These thresholds demonstrate sensory productions and depict the processuality of this experiment: the materials produced in and after the night in the forest are evolving and produce something different each time they are worked on. These written and recorded pieces were always producing a novel arrangement each time they were worked on. This part is entitled “Darkness”. Thirdly, responses under the title “Echoes from the forest” are set out from two participants after working together to produce pieces on the experiment. Fourth, the issue concludes with a ‘beginning’ in the form of questions on the matter of darkness and light, apparatuses and mattering methodologies. This was written by the editors and entitled “Will the Novembery forest insert itself?”. You are now reading the dis-connected version of the Editorial, and here you find only the first and forth part of the whole collective work. In the larger version where all the pieces are put together you will find the four parts as described above.

THE CONCEPTUAL-METHODOLOGICAL FOREST (HOW DOES THIS ‘MATTER’?)

The collective ideas that arise from all the pieces and various compositions in this special issue highlight affects and concepts that tackle interdependency and the more-than-individual. These include the initial bodily-cognitive-existential actualizations in the dark mossy forest when we felt that our ‘selves’ kept bleeding over our preconceived borders, dissolving or wavering as uncertain, collapsing into surrounding elements and other selves. But also the conceptual workings of these actualizations, into ‘soulbodies’, ‘one-as-many’, or ‘nomadic objects’ all aiming at knowing without domination. Knowing with categories that are always bleeding and uncertain. Locating the knowers as more-than-individual, as entangled compositions.

Collectively addressed are also the realizations of the power of one sense - vision - in conducting research, in creating knowledge, in producing reality. Vision is heralded to do methodology, even to be methodology. Vision and light (ability to see) seem to be the norm for knowledge production. Just think about the place of observations in mainstream educational research, or how often many of us habitually write or say: “When we look at…”, or “These perspectives…”, or “In the light of…” when presenting research. A critique of the power of vision rarely transverses disability studies and it took a deliberate walk, and activities in a dark forest, for us visually unimpaired, to be able to reach and concretely feel the weight of this one sense in research. When omitted, light or the ability to see showed in glaring conviction how our customs and habits of doing research (even critical, post-minded and feminist) were thoroughly dependent on this one sense. We began to feel the importance of deliberately crafting new habits. Of forcing ourselves to do research differently than we had before.

As human beings we inhabit a material world. We see it, hear it, touch it, smell it and travel in it. When in the dark we depend on our other senses: We seek refuge in hearing, touching and smelling, we seek anything we can grab onto, lean against or sit on. Our existence becomes alerted, subtle and aware, our voices become low and movements slow and deliberate. Methodology of darkness appears as if contrasting to the methodology that works in daylight. Darkness becomes a light and a means of seeing, yet capable of generating wholly different experiences. Darkness generates light as gradations of itself and seeing as imagining.

In the social scientific practices of making sense of the world Barad (2003, p. 801-803) tells us it is time to move beyond the anthropocenic landscapes where matter and mattering have less power than words and language in the world of the social and cultural. This brings attention to non-human matters and matterings; and their affect on us, and our affect on them. This is not to consider words and language as insignificant. Rather, it is to move from meaning and language centred significations to significance and affirmative sustainable ethics of one’s own conducts and life. This is done through giving matter at least the same value that is given for the transcend productions of it as language. (Barad 2007; Braidotti, 2006; Deleuze and Guattari 1994.) This is to follow Deleuze and Guattari’s philosophy of concepts as they employ Spinoza’s practical approach, in which philosophy is not transcendent and abstract, on the contrary, philosophy is the creative and the experimental operating to generating new. Deleuze writes according to Spinoza “there is no longer any difference between the concept and life”, “both elasticity of the concept and fluidity of the milieu are needed” as he engages with Spinoza’s ontology of naturalistic ethics away from the epistemologically centred philosophy (Deleuze 1988, p. 130). Therefore, the focus here moves from viewing discursive and material worlds in opposition towards envisioning them as produced by one another. This co-production becomes clear in the dark forest experiment where it is possible to be continuously and endlessly enlivened through various written, voiced and (photo)depicted expressions of the events and the encounters occurring in the nocturnal forest by the reader/viewer/listener (Davies and Gannon 2012). These expressions are produced again through the possible (re)productive movement of the reader/viewer/listener’s processes of (memorizing) the nightforest and its events.

Within Deleuze and Guattari’s thinking, ‘language’ and concepts are not independent tools enabling meanings as closed legitimated systems of thought to be conveyed. Rather, they are relational and made by situated mental, social and nature apparatuses. Therefore, each concept is always encountering the affect in the movement from perception to percept (Deleuze and Guattari, 1994; Guattari 1985; Deleuze, 1988; 1995; see also Massumi, 2015). This relationality brings in the ethics of experiment and the attempt here to express the mattering of darkness as it is felt, sensed and heard in a Novembery Finnish forest at night. This collectively shared (and produced) temporality and milieu creates understandings of darkness that reach beyond common understandings. The absence of light and all that is seen is usuallysymbolizing as the opposite of enlightened and rational humanist ways of knowing and being. However, as Barad elaborates:

Darkness is not mere absence, but rather an abundance. Indeed, darkness is not light’s expelled other, for it haunts its own interior. Diffraction queers binaries and calls out for a rethinking of the notions of identity and difference” (2014, p. 171).

In this experiment darkness brings in the ethics of difference compelling the experiment to express and articulate the mattering of darkness and its power through our senses while not perceiving darkness as monstrous or as otherness in its difference as Rosi Braidotti (1996, p. 135) elaborates on monstrousness as difference as follows:

Being figures of complexity, monsters lend themselves to a layering of discourses and also to a play of the imagination which defies rationalistic reductions… …The simultaneity of potentially contradictory discourses about monsters is significant; it is also quite fitting because to be significant and to signify potentially contradictory meanings is precisely what the monster is supposed to do.

Further:

As a signpost, the monster helps more than the interaction of heaven and earth. It also governs the production of differences here and now… …This includes the organic (sexual difference, nature, race) and inorganic (machinic or technological body double) other… …The peculiarity of the organic monster is that s/he is both Same and Other. The monster is neither a total stranger nor completely familiar; s/he exists in an in-between zone (1996, p. 141)

Instead, darkness is considered abundant and filled with forces that cannot be quantified or arranged but felt and sensed. Therefore, darkness functions here as the ethics in teaching us how to engage into something, become and become otherwise with something, which might not seem familiar or might not be easily and instantly approachable. This experiment produces knowledge differently for us through situated and created practices, making the not-seeing and blurry sense-lenses of the darkness practice accurate for queering our expectations of the binaries of science and shaking what we have learnt as the traditions of qualitative methodology.

The matter, the dark forest and its inhabitants, is perceived through our senses, and the matter and the produced sensations now take the lead and they no longer serve as the tools for ideas to materialize, instead, they are the narrators, ‘who’ employ us and our language, words and writing to make this production explicit and known outside the emerging event and encounter of nature. This is, as Deleuze insists with Spinoza, that both a philosophical comprehension produced by concepts and non-philosophical comprehension in terms of affects and percepts are needed, because: ‘the kinds of knowledge are modes of existence, because knowing embraces the types of consciousness and the types of affects that corresponds to it, so that the whole capacity of being affected is filled’ (Deleuze 1988, p. 82). In other words, this engagement with darkness embraces the importance of knowledge production within methodologies, in which both kinds of knowledges: the philosophical and sensory, are considered not as separate but as entangled. Difference is perceived as productive, and as the means to disturb normative understandings of ‘truth’ and legitimate knowledge by offering alternative ways of producing scientific knowledge on nature and on our ways of constituting various understandings of it.

As much as we wanted to break free, we have worked mostly within binaries of darkness and light. And with senses as separate individuated perceptions as collectively understood throughout the experiment. We have strived towards recognizing and conveying these binaries and individuations as necessarily entangled, but this is an ongoing project. As we talk about darkness we talk about light, when we talk about perceptions they are always inevitably both collective and singular productions. And always with ourselves as part of the phenomena (Barad 2007, p. 56):

Experimenting and theorizing are dynamic practices that play a constitutive role in the production of objects and subjects and matter and meaning. …theorizing and experimenting are not about intervening (from outside), but about intra-acting from within, and as a part of, the phenomena produced.

Acknowledgements

We (guest editors) would like to thank our reviewers for their valuable questions and advice on the editing of the publication and the technical assistant group for their work. We also thank all the participants for their contribution, including Riikka Hohti who attended the workshop but could not be part of the special issue. Thanks to Jayne Osgood for text editing work.

References

- Aitken, S. (2014). The ethnopoetics of space and transformation. Young people’s engagement, activism and aesthetics. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Appelbaum, D. (1995). The stop. New York: SUNY Press.

- Aranyosi, I. (2008). Seeing dark things. The philosophy of shadows. Australian Journal of Philosophy, 86(3), 513-515.

- Arendt, H. (1978). The life of the mind. New York: Harcourt.

- Banerjee, B., & Blaise, M. (2013). There’s something in the air: Becoming-with research practices. Cultural Studies <=> Critical Methodologies, 13(4), 240-245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708613487867

- Barad, K. (2012). On touching- the inhuman that I therefore am. A journal of feminist cultural studies, 23(3), 206-223. https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-1892943

- Barad, K. (2008). Living in a posthuman material world: Lessons from Schrödingers cat. In A. Smelik & N. Lykke (Eds.), Bits of life: Feminism at the intersections of media, bioscience, and technology (pp. 165-176). Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham: Durham University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822388128

- Bentham, J. (1988/1789) An introduction to the principles of morals and legislation. Prometheus Books.

- Berger, J. (2009/1980). Why look at animals? London: Penguin Books.

- Bergson, H. (1903/2007). An introduction to metaphysics. Mullarkey, J. & Kolkman, M. (eds. 2007), New York: Palgrave McMillan.

- Beston, H. (2003). The outermost house. A year of life on the Great beach of Cape Cod. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

- Braidotti, R. (1996). Signs of wonder and traces of doubt: On teratology and embodied differences. In N. Lykke (Ed.), Between monsters, goddesses and cyborgs: Feminist confrontations with science, medicine and cyberspace (pp. 135-152). London: Zeed Books.

- Deleuze, G. (1994). Difference and repetition. (P. Patton, Trans.) New York: Columbia University Press.

- Deleuze, G. (1990). The logic of sense (M. Lester, Trans.). New York: Columbia University Press.

- Deleuze, G. (1986). Nietzsche and philosophy (H. Tomlinson, Trans. 2002 ed.). London: Continuum (Originally published as Nietzsche et la philosophie, 1962).

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1994). What is philosophy? (G. Burchell & H. Tomlinson, Trans.). London: Verso (Originally published as Qu'est-ce que la philosophie?, 1991).

- Deleuze, G. (1995). Negotiations 1972-1990 (M. Joughin, Trans.). New York: Colombia University Press (Opprinnelig utgitt som Pourparlers, 1990).

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia (B. Massumi, Trans. 2004 ed.). London: Continuum (Originally published as Milles Plateaux, volume 2 Capitalisme et Schizophénie, 1980).

- Dillard, C. (2000). The substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen: Examining an endarkened feminist epistemology in educational research and leadership. Qualitative Studies in Education, 13(6), 661-681. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518390050211565

- Draper, R., & Knott, L. (2016). Labyrinthitis. Retrieved from http://patient.info/doctor/labyrinthitis

- Foucault, M. (1977) Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. London: Vintage books.

- Greenhough, B., & Roe, E. (2010). From ethical principles to response-able practice. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 28, 43-45. https://doi.org/10.1068/d2706wse

- Grosz, E. (2005). Bergson, Deleuze and the becoming of unbecoming. parallax, 11(2), 4-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13534640500058434

- Haraway, D.J. (1994). ‘A Game of Cat’s Cradle: Science Studies, Feminist Theory, Cultural Studies’, Configurations 2(1), 59-71. https://doi.org/10.1353/con.1994.0009

- Haraway, D. J. (2002). The persistence of vision. In N. Mirzoeff (Ed.), The visual culture reader (pp. 677-684). London: Routledge.

- Haraway, D.J. (2004a). The Promises of Monsters: a Regenerative politics for inappropriate/d others in D. J. Haraway (Ed.) The Haraway Reader. (pp. 63-124). London: Routledge.

- Haraway, D.J. (2004b). Cyborgs, Coyotes and `Dogs: A Kinship of Feminist Figurations. in D.J. Haraway (Ed). The Haraway Reader. (pp. 321-342). London: Routledge.

- Haraway, D.J. (2008). When Species Meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Haraway, D.J. (2008) 'Otherworldly Conversations, Terran Topics, Local Terms' in S. Alaimo, S. & S. Hekman (Eds) Material Feminisms. (pp. 157-187). Indiana: University Press.

- Haraway, D. (2012). Awash in urine: DES and premarin(r) in multispieces response-ability. Women's Studies Quarterly, 40(1 & 2), 301-316. https://doi.org/10.1353/wsq.2012.0005

- Harper, D. (2016). Labyrinth. Online etymology dictionary. Retrieved from http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=labyrinth

- Higgins, C. (2007). Interlude: Reflections on a line from Dewey. In Bresler, L. (ed.) International handbook of research in arts education. (pp. 389-394). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-3052-9_23

- Hotanen, J. (2008). Lihan laskos: Merleau-Pontyn luonnos uudesta ontologiasta. Helsinki: Tutkijaliitto, Episteme-sarja.

- Hultman, K., & Lenz-Taguchi, H. (2010). Challenging anthropocentric analysis of visual data: a relational materialist methodological approach to educational research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 23(5), 525–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2010.500628

- Ingold, T. (2011). Being alive: Essays on movement, knowledge, and description. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Jay, M. (1993). Downcast Eyes. The denigration of vision in 20th century French thought. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Kleinberg-Levin, D. M. (1988). The opening of vision: nihilism and the postmodern situation (Vol. 1). New York: Routledge.

- Koro-Ljungberg, M. (2016). Reconceptualizing qualitative research: Methodologies without methodology. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Kundera, M. (1983). Naurun ja unohduksen kirja (K. Siraste, Trans.). Helsinki: Werner Söderström Osakeyhtiö.

- Laruelle, F. (2013). Dictionary of non-philosophy (T. Adkins, Trans.). Minneapolis: Univocal.

- Law, J. (2004). After method. Mess in social science research. London: Routledge.

- Lee, N. (2008). Awake, asleep, adult, child: An a-humanist account of persons. Body Society, 14(4), 57-74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X08096895

- Macauley, D. (2009). Night and shadows. Environment, Space, Place, 1/2, 51-76. https://doi.org/10.7761/ESP.1.2.51

- Marks, J. (1998). Gilles Deleuze: Vitalism and multiplicity. London: Pluto Press.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1968). The Visible and the Invisible: Followed by working notes. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

- Mullarkey, J., & Smith, A. P. (2012). Introduction. The non-philosophical inversion: Laruelle's knowledge without domination. In J. Mullarkey & A. P. Smith (Eds.), Laruelle and non-philosophy (pp. 1-18). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Nietzsche, F. (1961). Thus spoke Zarathustra. London: Penguin.

- Saward, J. (2016). The centre of the Labyrinth. Retrieved from http://www.labyrinthos.net/

- Saward, J. (2016). The story of the labyrinth. Retrieved from http://www.labyrinthos.net/

- Sennett, R. (1990). The conscience of the eye: The design and social life of cities. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

- Schwartzman, H.B. (1993). Ethnography in organizations. Qualitative Research Methods Series 27. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412984119

- Sheet-Johnstone, M. (2009). The primacy of movement. Amsterdam: John Benjamin Publishing Company.

- Sorensen, R. (2008). Seeing dark things. The philosophy of shadows. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195326574.001.0001

- Trifonova, T. (2003). Matter-image or image-consciousness: Bergson contra Satre. Janus Head, 6(1), 80-114.

- Yourcenar, M. (1968). The Abyss: A novel: Noonday Press/Farrar.

- Zournazi, M. (2002). Hope: New philosophies for change. Annandale: Pluto Press Australia.