PhD Candidate Technology Enhanced Learning,

Lancaster University

Email: c.otoole1@lancaster.ac.uk; chris.otoole@nuigalway.ie

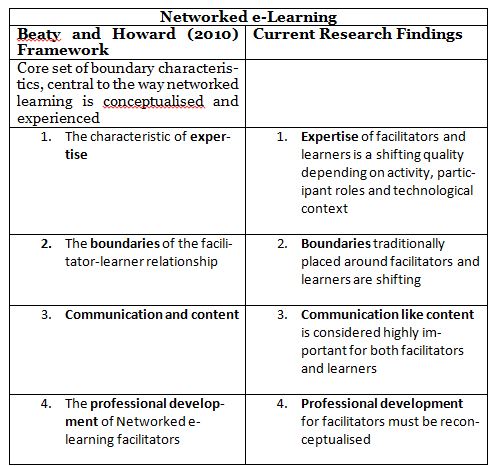

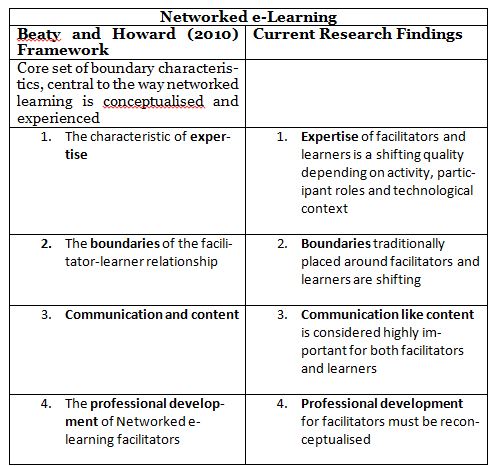

This phenomenological case study investigates the lived experiences of a group of virtual learning environment (VLE) postgraduate academic facilitators at Irish Universities where they have indicated that the nature of their relationship with learners is shifting. It aims for a deeper understanding of the phenomena of the changing facilitator – learner relationship in a Networked e-Learning environment (an asynchronous VLE with discussion forums, virtual labs and collaborative assignments). The author's role as a highly experienced facilitator provides particular and specific insight into the guiding facilitator's experiences during a time of institutional transition to Networked e-Learning. A theoretical framework based on Beaty and Howard (2010) is used to explore the networked relationship, i.e. their core set of boundary characteristics, central to the way networked learning is conceptualised and experienced which are the characteristic of expertise, the boundaries of the facilitator-learner relationship, communication and content and the professional development of Networked e-learning facilitators. Conclusions are presented as four themes describing how participants perceived the impact of Networked e-Learning on the changing facilitator – learner relationship. These themes highlight the differences between the current interpretative phenomenological analysis and the initial framework of Beaty and Howard (2010): (1) Expertise of facilitators and learners is a shifting quality depending on activity, participant roles and technological context; (2) Boundaries traditionally placed around facilitators and learners are shifting; (3) Communication like content is considered highly important for both facilitators and learners; (4) Professional development for facilitators must be re-conceptualised. Recommendations include the requirement to initiate revised forms of professional development for Networked e-Learning facilitators. Limitations included the relatively low number of participants.

Keywords: Case Study, Facilitator, Learner, Networked e-Learning, Phenomenology, Virtual Learning Environment (VLE)

With the advent of Web 2.0 and online communication technologies, Universities are increasingly moving to Networked e-Learning which has the potential to change the perceptions and practice of those engaged in learning within networked environments (McConnell, Hodgson & Dirckinck-Holmfeld, 2012). Few would argue that the nature of the facilitator – learner relationship is at the heart of Networked e-Learning, as their roles and responsibilities are transformed (Goodyear 2005; Hodgson & Reynolds 2005). Much guidance has arisen on academic practice for Networked e-Learning. The E-Quality in e-Learning Manifesto (2002) has outlined key goals for this relationship. Recent studies however suggest these key goals can be furthered to reflect the shifting roles, responsibilities and relationship (Beaty & Howard, 2010). This is particularly true in online education delivered with Virtual Learning Environments (VLEs).

Making an assumption that the facilitator – learner relationship in Networked e-Learning is the same as face-to-face learning because of similar personal connections may cause misleading practice. Because of the researcher's own status as a Networked e-Learning facilitator (who has experienced an enormous spectrum in terms of roles and responsibilities of facilitators), as well as his experience as an online and blended learning educator, the researcher questions how Networked e-Learning faculty relate to learners, their networked learning needs, and to the movement of facilitator/learner networked boundaries (Guldberg, 2008).Although faculty usually clearly outline the facilitator – learner relationship in their course expectations, the researcher was curious as to their unstated perceptions.

Thus the researcher asks the question, "How does the facilitator perceive the changing relationship between facilitators and learners within Networked e-Learning?”

The researcher considers four sets of relationship characteristics (four phenomena) through which to investigate the facilitator experience of Networked e-Learning as identified by Beaty and Howard (2010).These are the characteristic of expertise, the boundaries of the facilitator-learner relationship, communication and content, and the professional development of Networked e-Learning facilitators. These same characteristics do not manifest themselves in the same forms in face to face learning where there is an absence of mediation using digital networked technology. In this research, the chosen characteristics provide an opportunity to consider the changing facilitator-learner relationship within VLE networks, the nature of their activity and how this can be improved by networked facilitator professional development.

Few published articles, to any extent focus on these phenomena of the changing facilitator – learner relationship in a Networked e-Learning environment in relation to these characteristics, and none focus on the lived experience of facilitators themselves. Therefore, this research explores the lived experiences of facilitators in a Networked e-Learning VLE.

To understand the purpose and position of this research, it is necessary to outline the researcher's own ontological and epistemological presuppositions underlying this study. The researcher sought a methodology that allowed exploration of the lived experience of VLE Networked e-Learning facilitators and consequently chose a phenomenological case study. Understanding how that experience unfolded for each facilitator was an important anticipated outcome, but what became apparent to the author was the need to understand how these experiences were socially and culturally constructed in specific Networked e-Learning VLE contexts. Thus the researcher's position is taken from a constructivist/interpretivist paradigm where the view of the world is that knowledge is based on experiences that are socially constructed (Creswell, 2009) and emphasises the importance of personal perspective and interpretation. The research purpose has personal significance to the researcher given his own direct connection and experience of being a Networked e-Learning facilitator within Networked e-Learning VLEs.

The study organisations, on which the research was conducted, were united with online learning. In this case online learning is understood as Networked e-Learning or "Technology Enhanced Learning” which means the use of technology for supporting and enhancing learning practice (Mayes & de Freitas, 2004) and the use of "the Internet to access learning materials, to interact with the content, instructor, and other learners and to obtain support during the learning process, in order to acquire knowledge, to construct personal meaning, and to grow from the learning experience” (Anderson & Elloumi, 2004, p37).

The conceptual framework of the present research is based on the framework of Beaty and Howard (2010), i.e. their core set of boundary characteristics, central to the way networked learning is conceptualised and experienced.

The researcher chose this framework as these core characteristics provide an opportunity to consider the changing facilitator-learner relationship within VLE networks, the nature of their activity and how this can be improved by networked facilitator professional development.

The principles of the framework that are important to this research are the characteristic of expertise, the boundaries of the facilitator-learner relationship, communication and content and the professional development of Networked e-learning facilitators.

This small-scale research employed the Beaty and Howard (2010) framework to explore the changing relationship of facilitators to learners within the networked VLE.This is done by examining the relationship based on the above four key boundary characteristics, gaining participant views of each characteristic.

This framework is specifically used in this paper in formulating the questions posed to the participants, as well as in informing the research questions with deeper understanding of networked facilitator-learner relations in this context.

A review of the available literature provides a wealth of information of Networked e-Learning (Steples & Jones, 2002; Jones, Ferreday & Hodgson, 2008; McConnell, Hodgson & Dirckinck-Holmfeld, 2012). For example Jones et al., (2008) synthesise the research on the general effects of Networked e-Learning. However more recently, authors have moved towards the concept of network participant roles and responsibilities (Beaty & Howard, 2010). These qualities are an integral part of the E-Quality in e-learning Manifesto (2002).

The changing facilitator – learner relationship in a Networked e-Learning VLE appears to be a complex set of phenomena to define. Beaty and Howard (2010) suggest that Networked e-Learning has initiated shifts in the role, responsibilities and experiences of both facilitators and learners. However, other authors, such as Baran, Correia, and Thompson, (2011) highlight the unrecognisable nature of the shifts and emphasise the frustrating point that individuals recognise shifts when they experience it, but find the phenomena difficult to define.

A review of the literature focused on professional practice within Networked e-Learning VLEs helps to illuminate the current study. The areas of expertise, boundaries, communication and content, and professional development were chosen based on Beaty and Howard's (2010) assertions.

The core change in the facilitator-learner relationship and the associated pedagogical design of Networked e-learning VLEs appears to lie in the shifting quality of expertise. Prior to the establishment of Networked e-Learning, VLE facilitators were viewed as experts (Beaty & Howard, 2010). However Networked e-learning has increasingly fore-grounded pedagogies based on shared responsibility (Goodyear, 2005; Hodgson & Reynolds, 2005).

It was thus theorised that VLE facilitators should have an equal level of influence within VLEs (Downes, 2010). Both facilitators and learners would co-create and collaborate using their joint expertise. Furthermore, the focus on work-based learning and professional education means that learners are now frequently experts in their profession (Bawne & Spector, 2009). In addition learners frequently hold higher levels of expertise in the use of ICT and Web 2.0 networked technologies. The author's experience supports this belief as having experienced networks between learners enabling unions of learners as experts rather than the lone facilitator.

It is important to note that Networked e-Learning pedagogical design does not imply the elimination of expertise within Networked e-Learning, but rather a quality that moves between members of an e-learning network, both facilitators and learners, resting on shifting and transient boundaries (Beaty & Howard, 2010). Thus expertise appears transactional rather than hierarchical. However as there is an absence in the literature of any indication as to what any shift in expertise depends on, the author seeks to investigate these dependencies.

Much literature asserts that there are no easily identified boundaries to facilitator-learner communities within Networked e-Learning. Many have questioned the relevance of a learning community (Castells, 2011). The author finds notable tension in these reviews.

Certain inferences about the facilitator-learner network boundary can be made from research that critiques the blanket use of the community concept. Jones and Esnault (2004) reported that a network doesn't privilege the closeness of community rather it serves to encompass all kinds of links and relationships. Such indicators suggest that networked technologies enable the development of hybrid networks outside of the facilitator initiated network, but which are still linked and through which learners navigate depending on their needs. In the author's own experience, it is unclear whether for VLE facilitators, the use of Networked e-Learning correlates with the diffusion of arbitrary boundaries and consequently the changing facilitator-learner relationship.

The current study sets out to investigate the facilitator's lived experience of a VLE e-Learning Network to gain additional insights about the participants ‘tight-loose' engagement (Jones, Asensio & Goodyear, 2000), its hybrid networks and their influence on the boundaries of Networked e-Learning.

Dialogue has always been the key to facilitation. However, with Networked e-Learning, it seems to become the basis for the learning rather than the way to impart knowledge. Within the literature, Guldberg (2008) reports that the communication itself becomes the essence of the ‘content' used. These perceptions point towards content that is co-created and enabled by dialogue. The author agrees with this from his own experience, as he frequently uses previously recorded networked online discussions as actual content for subsequent ones. To explore this and the influence of communication in the facilitator-learner relationship within Networked e-Learning VLEs, the author seeks to explore how facilitators communicate and in so doing generate content.

Oastashewski (2010) maintains that the above changes in the facilitator-learner relationship have consequences for their professional practice, while Beaty and Howard (2010) go further in breaking down the distinction between facilitators and learners, viewing both as practitioners. On reflection, the author's own experience of Networked e-Learning facilitator professional development appeared to be based principally on advancement of networked technology specific skills.

Dirckinck-Holmfeld's (2006) work reiterates much prior literature and notes we should rethink the role of Networked e-Learning facilitators. However its main value lies in highlighting the need to consider the educational and professional diversity of facilitators of such networks.

While it is interesting that Beaty and Howard (2010) argue that facilitators practice will be coloured by the realities of their prior experience, this reveals a double challenge for professional development in that it must thus utilise the pedagogies and technology of networked learning itself. This is also suggested by Baran, Correia, and Thompson (2011) who indicate that facilitators will need to experience the changing facilitator-learner relationship outlined above in order to motivate their professional development and practice within TEL for Networked e-Learning. The researcher believes, therefore, that a study which carefully looks at the lived experiences of facilitators within Networked e-Learning VLEs deserves serious exploration. Focusing on the lived experience is powerful for understanding subjective facilitator perceptions of the changing facilitator-learner networked learning relationship, cutting through the clutter of taken-for-granted assumptions and conventional wisdom.

This study represents an initial exploration of the perceptions of facilitators within a Networked e-Learning VLE of the changing facilitator – learner relationship. As such it is foundation research in this area. Given the time constraints with this short study, it was only possible to interview two participants for a short time and ascertain written reports from two other participants. In addition, all four facilitators (one being the researcher himself) were known to the researcher. They were ICT academic VLE facilitators within third level Universities within Ireland. Future research could widen the context to include cross-sector studies with larger sample sizes in order to perform further analyses to confirm the changing facilitator-learner relationship within Networked e-Learning VLEs.

The researcher acknowledges the possibility of researcher bias within this study given his involvement as both author in the original paper and a participant, and the professional relationships that have been sustained over time with the other selected participants. Where the source of bias could have appeared in particular was in conducting the interviews (Cohen et al., 2011) and soliciting written reports. Because of this, every effort was taken to ensure questions were phrased in an open manner, without pre-empting responses. Opportunities were also offered for participants to elaborate on experiences that the researcher would have knowledge of.

Case study methodology enables researchers to closely study the data within a specific context using a small number of participants "to provide an in-depth understanding of the case” (Creswell, 2007, p.74). In addition "phenomenology provides a deep understanding of a phenomenon as experienced by several individuals”, (Creswell, 2007, p.62). As a result I employed the qualitative method of a phenomenological case study. In alignment with this approach, the researcher has focused on the experiences of individual facilitators and not on a comparative examination of their experiences in contrast to other facilitators.

This design consists of an interpretive, exploratory, phenomenological single-case study of the phenomena based on the views of three independent participants (emic) as well as the views of the researcher (etic), as the fourth participant (Runeson & Host, 2008).The researcher subsequently conducted an analysis of themes in order to explore "the deep meaning of individual subject's experiences” (Rossman & Rallis, 1998, p.72). The study is interpretive in the sense that it aims to understand the phenomena through the experiences and interpretations of the participants (Runeson & Host, 2008). It is exploratory in that it looks for new insights of the phenomena and seeks to generate ideas for further research (Robson, 2002; Yin 2014). The objective of this investigation is to highlight the changing facilitator – learner relationship in a Networked e-Learning environment and to initiate further investigation of the phenomena, all of which makes phenomenological case study design a suitable for this small-scale study.

Purposive sampling was employed in this study. This was due to the limited time and scale of the research and also the need to gather rich data from in-depth experiences and different perspectives of the phenomena (Creswell, 2007; Patton, 1990). Participants were VLE facilitators of differing experience, age groups, gender and educational backgrounds as variation in experience is essential (Akerlind, 2004). Selection criterion was having more than four years' experience as an online academic facilitator within virtual learning environments of academic institutions.

From an initial list prepared based on the above variables, four participants were recruited through email invitation containing a link to the research project participant consent form as well as a participant information sheet. It therefore aligns to Smith, Flowers and Larkin (2009), who advocate that a small sample size is acceptable as phenomenology is "concerned with understanding particular phenomena in particular contexts” (p.49).

The first participant (who was also the researcher) was 46 years old, male and of Irish descent. The second participant was 27 years old, female and of Irish descent. The third participant was 55 years old, male and of Irish descent. The fourth participant was 34 years old, female and of Irish descent. The researcher was well known to all of the participants. Therefore, the researcher's insider position, background and perspectives have influenced the rationale, operationalisation and interpretation of this research. However, insider mitigation techniques proposed by others (Mercer, 2007) were employed.

Ethical and consent issues were duly considered given the nature of the data to be collected (Kanuka & Anderson, 2007, p.5). Ethical approval was granted from Lancaster University, and written permission to invite the trainees was not required as they were not representing their employers. The researcher obtained verbal consent to record the interviews. They were informed that the data obtained would be anonymised. Participants were informed that participation in the research was voluntary, and that they could choose not to answer specific questions.

In case study research, emphasis is placed on having multiple sources of evidence. In single-case design a minimum of two sources of evidence is advised for validity purposes (Yin, 2014).

The primary set of data collected in this study was semi-structured interviews undertaken with two participants; this is common in case study research (Cohen, Manion & Morison, 2011). Of all interview types, semi-structured, face-to-face were used in this study to allow the researcher to delve deep using follow-on questions and ask for clarifications when required. As opposed to structured and non-structured interviews, semi-structured with open ended questions cater for structured yet flexible interview design (Cohen et al., 2011; Barriball & While, 1994). Here the researcher could pre-design questions catering for standardisation across both interviews, increasing data reliability but allowing participants to inform the research beyond the questions as the researcher was allowed to probe the participants and ask follow-on questions. The two semi-structured interviewees were limited to 30 minutes and took place in a place and time chosen by the participant ensuring it would not affect the audio-recording quality. The interviews were subsequently transcribed.

Secondary data was gathered in the form of written reports requested of the other two participants' experience based on open-ended questions. The researcher obtained written consent to obtain the written reports. Both participants completing written reports were advised that they should not spend more than forty minutes on the written report. They were given a total of five days to complete, with a reminder email sent after three days.

Questions for both the interviews and written reports were designed based on the underlying research question, the theoretical framework and issues that were highlighted in the literature review. These questions were piloted with experienced VLE facilitators and revised based on feedback. Both transcribed interviews and written reports were initially reviewed for completeness by the author. This gave a closer look at the data collected, and provided some familiarity with the data. This was viewed as a first step in the analysis and, once reviewed the data was re-read systematically to allow for patterns and themes to emerge.

Guided by the theoretical framework and the research question, the researcher took account of all relevant data while conducting the analysis. Interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA) was performed, including the following: (a) movement from what is unique to a participant to what is shared among the participants, (b) description of the experience which moves to an interpretation of the experience, (c) commitment to understanding the participant's point of view, and (d) psychological focus on personal meaning-making within a particular context (Smith et al., 2009). Following the IPA process, the researcher conducted initial noting, which includes descriptive, linguistic, and conceptual comments (Smith et al., 2009).

After completing initial noting on each participant's data, the researcher searched for emerging themes across all participants by examining discrete sections of the written reports and interview transcript and simultaneously recalling what had been learned during the analysis up to this point. The themes not only reflected the participants' original words and thoughts but also the researcher's interpretations. In the development of themes, the researcher supported each theme again by descriptive, linguistic, and conceptual comments made by each of the participants.

The process produced a rich and varied description of the participants' facilitation experience, their perception of the changing facilitator – learner relationship within Networked e-Learning and the shifts in the role, responsibilities and experiences of VLE facilitators and learners. The results of the data analysis are organised by four themes:

Expertise of facilitators and learners is a shifting quality depending on activity, participant roles and technological context

Boundaries traditionally placed around facilitators and learners are shifting

Communication like content is considered highly important for both facilitators and learners

Professional development for facilitators must be reconceptualised

The themes developed in this study illustrate to what extent and in what ways the facilitator experiences Networked e-Learning initiating shifts in the role, responsibilities and experiences of facilitators and learners within a VLE. These themes highlight the differences between the current interpretative phenomenological analysis and the initial framework of Beaty and Howard (2010)

The section below will describe each of these in more detail, and support these with extracts from the written reports and interview transcripts. Written reports are identified as [W1] and [W2]. Interview transcripts are identified as [I1] and [I2].

The author found that all of the participants in this study had moved away from the taken-for-granted relationship between facilitators and learners. One participant recalled,

"Since becoming a Networked e-Learning facilitator using our VLE, I definitely feel I am no longer viewed as the expert. In one such instance, a learner with considerable commercial experience and knowledge in the subject area used his expertise in the technological context to provide supporting real world examples to scaffold the course content provided, which I could not.” [I1]

Another participant further identified the shifting quality of expertise when working on a group activity where many learners were clearly experts and the facilitator not. As this participant put it,

"… when attempting a distributed computer programming activity, I suggested an approach to the design and development based on my most recent practice and the course content. However, this approach had since been replaced with a more efficient approach based on newer technology and practice. Several learners who held roles as distributed computing programmers were able to point this out to the group and provide supporting examples for our activity. This clearly indicated that depending on the activity and participant role, the learner is frequently more of an expert than the facilitator.” [W2]

All four participants highlighted the shifting boundaries within Networked e-Learning VLEs. The technologies enabling networked learning diffuse the boundaries we place around the facilitator and learners within the VLE.

"I feel that as a facilitator I am now a fellow learner. I see myself providing a particular form of expertise assisting the learners to maximise the potential of the VLE network. I structure learner interactions but also actively involve learners in this.” [I1]

One participant recalled an occasion where groups of learners were subdivided to perform group tasks based on subject specifics. Here the facilitator perceived the existence and use of hybrid networks, where learners participated via multiple connections in accordance with the sub group needs and objectives.

"On one occasion, I posted a discussion question to explain ‘test driven development' within software engineering as defined within the course content. The learners moved outside the VLE network to source material and supporting examples for their explanation. In essence they navigated hybrid networks to accomplish the task.” [W1]

These participant perceptions seem to support the idea that Network e-Learning doesn't privilege the closeness of a VLE community but rather it encompasses all possible links and relationships (Jones & Esnault, 2004). In this view of Jones & Esnault, the boundaries around Networked e-Learning facilitators and learners cover relationships that have ‘varying degrees of proximity'. It appears that hybrid networks of learners are emergent and their associated boundaries shaped by the specific networked activity.

All participants in this study experienced great benefit from the communication afforded by the networked technology. One participant recalled the first virtual lab exercise where they had experienced networked communication and noted the increased activity, the higher standard of group communication, and overall the much improved student grades.

"I could immediately see how the level of learner communication increased significantly. Their collaboration when working on understanding the concepts and finding solutions to the tasks was increased greatly and their overall understanding and level of knowledge on the subject increased substantially.” [W2]

"One of my learners commented to me that the ability to communicate in an online networked way to complete the weekly activities enabled them to grasp the concepts better and learn more effectively than had the weekly content been simply distributed to all learners without the ability to communicate and network online.” [I2]

All participants expressed the view that with Networked e-Learning, the boundaries between communication and content are now less defined.

"… previously I believed as a facilitator that providing course content was more important than providing communication with digital media for my learners. However, the increased level of learning and higher learner grades that I have experienced with Networked

e-Learning has highlighted that the boundaries between the content and communication are less defined. I now see them as duel elements of one consortium, in which both facilitators and learners are engaged in the creation and communication of content as the basis of true networked learning.” [W1]

This indicated that Networked e-Learning within VLEs by facilitators had consciously made a shift towards dialogue built on social-constructivist pedagogies where their approach to online facilitation focuses on dialogue within networked experiences. This is further evidenced by one participant (the author, a highly experienced facilitator) who explained that the training schedule for all VLE facilitators in one of his organisations

"…included a development plan for our facilitators to include significant dialogue within their facilitation so that both their learners and themselves engage in the creation and communication of content and not to fore-ground content over communication” [I2].

In addition to the above changes to the expectations, practice and role of the facilitator and learner initiated by Networked e-Learning, all four participants perceived significant implications for their continuing professional development as Networked e-Learning VLE facilitators.

"I see significant challenge in educating new facilitators for their Networked e-Learning role. They will need the ability to manage expectations and practice of their fellow networked learners whilst also adjusting their own expectations as facilitators.” [I1]

Another participant further identified this need in the context of changing identities. As this participant put it,

"…and not only will it involve the development of new skills and practical approaches but new ways of thinking aligned to the development of new identities for us as facilitators and also for our learners...” [W1]

This study showed that Networked e-Learning VLE facilitators believe that Networked e-Learning has initiated shifts in the role, responsibilities and experiences of both facilitators and learners, and affirms the belief of Beaty and Howard (2010). In addition the study showed that facilitators also believe the nature of these shifts emphasises the need to investigate new forms of professional development for those who facilitate and support Networked e-Learning. This agrees with Fullan (2013), in that facilitators should be made aware of the benefits of pedagogies and technology of networked learning and how these can improve their professional practice. It also strengthens the view of Zenios, Goodyear and Jones (2004) who believe that institutions need to adapt their approach to such professional development to include strategies that support the identification and development of core competencies and skills focused on the technological fundamentals of networked e-learning and the dialogic pedagogies it requires.

The findings show that expertise of facilitators and learners is a shifting quality depending on activity, participant roles and technological context. This moves away from the traditionally assumed relationship between facilitators and learners and is aligned to Beaty and Howard (2010) who no longer view learners as acolytes. In agreement with Jones and Esnault (2004) the findings question the boundaries that can be placed around those engaged in Networked e-Learning via technology enhanced processes and practices, as these enable connectivity to networks that exist outside the learning process initiated by the facilitator. This is aligned with the view of Brown (2010) who believes that learners and facilitators are increasingly members of multiple networks.

In accordance with the opinion of Hodgson, McConnell and Dirckinck-Holmfeld (2012), the findings assert that in today's Networked VLEs with enhanced connectivity, the demarcation between communication and content is now less defined. Facilitators recognise the increasing importance of dialogue within their networked facilitation practice. This supports Guldberg (2008) who believes that dialogue built on socio-constructivist pedagogies frequently defines the content of networked learning environments. This is also aligned with the view of Hodgson et al., (2012) who believe learners as well as facilitators are engaged in the creation and communication of content.

"I believe the level of connectivity in VLEs today afforded by networked technology highlights the notion that dialogue is now negotiated between the facilitator and learner as it becomes the foundation for the networked learning rather than the means to transfer knowledge. The communication now underpins the content.” [W1]

Consequently the expression of expertise will also rest on the facilitator-learner dialogue and the learner to learner dialogue as asserted by Guldberg (2008).

The results are highly significant because as indicated, if expertise of facilitators and learners is a shifting quality, and boundaries placed around them are also shifting, and communication for both is as important as creation of content, then the approach to professional development must be correspondingly re-conceptualised (Zenios, Goodyear & Jones, 2004). The results further scaffold those found by Beaty and Howard (2010) and show that the Networked e-Learning has a profound influence on the changing facilitator-learner relationship within VLEs. More specifically they highlight the differences between the initial framework of Beaty and Howard (2010) and the current research.

Figure 1. Comparison of Beaty and Howard (2010) framework and current research

This qualitative study, as an attempt to explore the changing facilitator-learner relationship within Networked e-Learning VLEs, through the lens of facilitators, is an important complement to the existing literature in the area of Networked e-Learning, within the context of technology enhanced learning. Although the study had its limitations, the findings are compelling. From a practical standpoint, the findings can inform other facilitators of Networked e-Learning VLEs about the shifting facilitator-learner experiences they may encounter, and how they can address this as part of their professional practice and training requirements. Therefore it may be possible for experienced facilitators to communicate to all, the appropriate skills and experience required for best practice Networked e-Learning facilitation.

The key things to take from this study are to be aware of the shifting quality of expertise of facilitators and learners depending on activity, participant roles and technological context, the shifting boundaries placed around facilitators and learners, the consideration of communication like content as highly important for both facilitators and learners and the need re-conceptualised professional development for facilitators. These themes as evidenced in the research findings provide clear answers to the research question, identifying distinct changes between the relationship of facilitators and learners within Networked e-learning. As regards the practice context, this alone may go a long way toward helping to improve the facilitator-learner relationship and ultimately the learning within Networked e-Learning VLEs.

Based on the findings of this study, it is vitally important to promote and allow for a fundamental understanding on the part of the facilitator and their institutions of the shifting nature of the facilitator-learner relationship (roles, responsibilities and experiences) within Networked e-Learning VLEs for maximising the networked learning experience. As Schneckenberg (2010) advocates, Networked e-Learning within TEL asks the facilitator to reflect on the power relationships and processes involved and to ensure change is supported by institutional structures and cultural values.

Future research could explore how learners themselves experience the changing facilitator-learner relationship with regard to the expectations, practice and role of the facilitator and learner initiated by Networked e-Learning and how they feel nature of the facilitator-learner relationship is shifting.

Despite its relative newness, using the Beaty and Howard (2010) core networked learning relationship characteristics as a theoretical framework enabled exploration of the pedagogical implications for being a Networked e-Learning facilitator and how to create meaningful learning opportunities for networked VLE e-learners. Following this research study, there is a requirement to initiate revised forms of professional development for Networked e-Learning facilitators. This is valuable knowledge gained and something that should be investigated further in time.

Åkerlind, G.S. (2004) A new dimension to understanding university teaching.

Teaching in Higher Education, 9(3), 363 – 375.

Anderson, T. & Elloumi, F. (2004). Theory and Practice of Online Learning.

Athabasca University.

Baran, E., Correi, A. P., & Thompson, A. (2011). Transforming online teaching practice: crtical analysis of the literature on the roles and competences of online teachers. Distance Education, 32(3), 421-439.

Barriball, K. L., & While, A. (1994). Collecting data using a semi-structured interview: A discussion paper. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 19(2), 328-335.

Bawane, J., & Spector, J. (2009). Prioritization of online instructor roles: implication for competency-based teacher education programs. Distance Education, 30(3), 383-397

Beaty, L. L., & Howard, J. (2010). Re-Conceptualising the Bounderies of Networked Learning: The Shifting Relationship Between Learners and Teachers. In L. Dirckinck-Holmfeld, V. Hodgson, C. Jones, M. de Laat, D. McConnell, T. Ryberg Eds.), Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Networked Learning. Retrieved April 3, 2016 from: http://www.lancs.ac.uk/fss/organisations/netlc/past/nlc2010/info/confpapers.htm

Brown, S. (2010). From VLEs to learning webs: the implications of Web 2.0 for learning and teaching. Interactive Learning Environments, 18 (1), 1-10

Castells, M. (2011). A Network Theory of Power, International Journal of Communication, 773-787.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison K. (eds.)(2011). Research Methods in Education, 7th Edition, London: Routledge.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative Inquiry research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches (Second ed.). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research Design. Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches, 3rd Edition, Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Downes, S. (2010). The role of the educator. Huffington Post Education. Retrieved April 3, 2016 from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/stephen-downes/the-role-of-the-educator_b_790937.html

Dirckinck-Holmfeld, L.(2006).Designing for Collaboration and Mutual Negotiation of Meaning: Boundary Objects in Networked Learning Environments. In S. Banks, V. Hodgson, C. Jones, B. Kemp, & D. McConnell (Eds.),Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Networked Learning 2006: Symposium: Relations in Networks and Networked Learning, organised by Chris Jones. Lancaster University.

E-Quality Network (2002) 'E-quality in e-learning Manifesto' presented at the Networked Learning 2002 conference, Sheffield. Retrieved April 6, 2016 from http://csalt.lancs.ac.uk/esrc/

Fullan, M. (2013). Stratosphere: Integrating technology, pedagogy, and change knowledge. Don Mills, Canada: Pearson.

Goodyear, P. (2005). Educational design and networked learning: Patterns, pattern languages and design practice. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 21(1), 82-101.

Guldberg, K. (2008). Adult learners and professional development: Peer-to-peer learning in a networked community. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 27(1), 35-49.

Hodgson, V., McConnell, D., & Dirckinck-Holmfeld, L. (2012). The Theory, Practice and Pedagogy of Networked Learning. In L. Dirckinck-Holmfeld, V. Hodgson, & D. McConnell (Eds.), Exploring the Theory, Pedagogy and Practice of Networked Learning. (pp. 291-307). Chapter 17.Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

Hodgson, V., & Reynolds, M. (2005). Consensus, difference and ‘multiple communities' in networked learning. Studies in Higher Education, 30(1), 11-24

Jones, C., Asensio, M., & Goodyear, P. (2000) ‘Networked learning in higher education: practitioners' perspectives' ALT-J, The Association for Learning Technology Journal, 8(2), 18 -28.

Jones, C. & Esnault, L. (2004) ‘The metaphor of networks in learning: communities, collaboration and practice', in Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Networked Learning, eds S. Banks et al., Lancaster University, Lancaster, 317–323. Lancaster University and The University of Sheffield,Lancaster.

Jones, C.R., Ferreday, D., & Hodgson, V. (2008). Networked learning a relational approach: Weak and strong ties. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 24(2), 90–102.

Kanuka, H., & Anderson, T. (2007). Ethical Issues in qualitative e-learning Research. International Journal of Qualitative Research, 6(2), 1-14.

Mayes, T. and de Freitas, S. (2004) JISC e-Learning Models Desk Study. Stage 2: Review of e-learning theories, frameworks and models. Retrieved April 9, 2016 from http://www.jisc.ac.uk/uploaded_documents/Stage%202%20Learning%20Models%20(Version%201).pdf

Markee, N. (2012). Emic and Etic in Qualitative Research. The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

McConnell, D., Hodgson, V., & Dirckinck-Holmfeld, L.(2012).Networked Learning: A Brief History and New Trends. In L. Dirckinck-Holmfeld, V. Hodgson, & D. McConnell (Eds.),Exploring the Theory, Pedagogy and Practice of Networked Learning.(pp. 3-24). Chapter 1.New York: Springer Science+Business Media B.V.. DOI:10.1007/978-1-4614-0496-5_1

Mercer, J. (2007) The Challenges of Insider Research in Educational Institutions: Wielding a double-edged sword and resolving delicate dilemmas Retrieved 25 Oct 2015, from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03054980601094651

Moustakas, C. E. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ostashewski, N. (2010). Online technology teacher professional development courselets: Design and development. In D. Gibson & B. Dodge (Eds.), Proceedings of the Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference 2010 (pp. 2329–2334). Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, Ca: Sage Publications.

Robson, C. (2002). Real world research. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

Rossman, G.B., & Rallis, S.F. (1998). Learning in the field: An introduction to qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Runeson, P. & Host, M. (2008). Guidelines for conducting and reporting case study research in software engineering. Empirical Software Engineering, 14(2),131-164

Schneckenberg, D. (2010). Overcoming Barriers for eLearning in Universities – Portfolio Models for eCompetence Development of Faculty. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(6), 979–991.

Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretive phenomenological analysis: Theory, method, and research. London: Sage.

Steeples, C., & Jones, C. (Eds.). (2002). Networked learning: Perspectives and issues. London: Springer-Verlag.

Zenios, M., Goodyear, P., & Jones, C. (2004). Researching the impact of the networked information environment on learning and teaching. Computers and Education 43(1-2), 205-213.

Appendix A Definition of Terms in this research context

|

Emic |

Insider perspective (Markee, 2012) |

|

Etic |

Outside perspective (Markee, 2012) |

|

Experience |

Wise and skilful through doing |

|

Facilitator |

Helps the learner group navigate the VLE network, structures and monitors activities |

|

Improve |

Make better |

|

Learner |

Receives teaching, guidance and support from facilitator |

|

Lived Experiences |

Emphasizes the importance of individual experiences of people as conscious human beings (Moustakas, 1994). |

|

Networked |

Learning in which information and communications technology (ICT) is used to promote connections: between one learner and other learners, between learners and tutors; between a learning community and its learning resources (Steeples and Jones, 2001; Goodyear et al., 2004) |

|

TEL |

Technology Enhanced Learning |

|

VLE |

Virtual Learning Environment |

Chris O' Toole

BA, Dip Law, Dip CCI, MSc CCI, QFA, FIAP, MBA Technology Management,

PhD Candidate Technology Enhanced Learning, Lancaster University

Chris O' Toole is a teaching professional with an established reputation in e-Learning and integration of technology into daily learning; He has a passion for research and evidence based practice to support the development of Technology Enhanced Learning; With over 25 years commercial experience in ICT, Engineering and Technology Management roles within leading companies in Ireland and the UK, Chris is a Technology Enhanced Learning Specialist and adjunct e-Lecturer in ICT, Engineering and Management.

Chris, a PhD candidate at Lancaster University, has written a paper called: "Networked e-Learning: The changing facilitator – learner relationship, a facilitators' perspective; A Phenomenological Investigation”. This phenomenological case study investigates the lived experiences of a group of virtual learning environment (VLE) postgraduate academic facilitators at Irish Universities where they have indicated that the nature of their relationship with learners is shifting. It aims for a deeper understanding of the phenomena of the changing facilitator – learner relationship in a Networked e-Learning environment (an asynchronous VLE with discussion forums, virtual labs and collaborative assignments).The author's role as an experienced facilitator provides particular and specific insight into the guiding facilitator's experiences during a time of institutional transition to Networked e-Learning.The researcher collected data from semi-structured interviews and self- written reports. The key things to take from this study are to be aware of the shifting quality of expertise of facilitators and learners depending on activity, participant roles and technological context, the shifting boundaries placed around facilitators and learners, the consideration of communication like content as highly important for both facilitators and learners and the need re-conceptualised professional development for facilitators.

This research was undertaken as part of the PhD in E-research and Technology

Enhanced Learning in the Department of Educational Research at Lancaster University. I am pleased to acknowledge the contribution of Dr. Brett Bligh, Dr. Murat Oztok, Mr. Vlad Chiriac and Miss. Joanna Beaver in supporting the development of this study and its report.