Co-founder of the Patient Voices Programme

PhD candidate

Manchester Metropolitan University

Email: pip@pilgrimprojects.co.uk

Opportunities to disseminate the stories of patients and those who care for them via the internet create new dilemmas with respect to ethical processes of consent and release. The possibility of utilising images as well as words further complicates this issue.

Balancing the need to protect the safety and security of those who share their stories with their own desire for their stories to be widely heard presents a complex blend of ethical issues.

The Patient Voices programme has been helping people create and share digital stories of healthcare since 2003. During that time, careful thought has been given to the development of a respectful process that both empowers and protects storytellers, affording time at every stage of the process to reflect and make informed decisions about consent, sharing and dissemination.

This paper describes how that process has been developed and explores the issues that it was designed to address.

Keywords: Digital storytelling, healthcare, ethics, informed consent, respect, reflection.

‘Primum non nocerum. (First do no harm.)’

Hippocrates – Greek physician and founder of the Hippocratic School of Medicine

Digital storytelling was developed in California in the mid-1990s by what became the Center for Digital Storytelling (CDS), and is now (as of 2015) StoryCenter, as a means of enabling ordinary people to utilise multi-media tools in order to share stories about their lives (Lambert, 2002). Early use of the methodology in America was primarily in the field of community development, and came to the UK initially via BBC’s Capture Wales Project. Gradually the method took root in education, youth work, public health, the environment, domestic violence, immigration, research, museum work and, more recently, marketing, advertising, journalism and many other contexts.

Indeed, the term ‘digital storytelling’ has become somewhat ubiquitous. When used in this paper, it refers to the participatory workshop approach first developed by CDS that builds on the emancipatory ideals of Paulo Freire (Freire, 1973), promoting social justice by giving ordinary people the opportunity for their voices to be heard. Through the provision and creation of what Illich referred to as ‘convivial tools’ (Illich, 1973), people are able to represent their lives through voice, image and music and convey them via digital media. The result is a short, multi-media tapestry imbued with authenticity and rich with emotion, offering viewers an opportunity to walk in the storyteller’s shoes for just a few moments.

The growing popularity and acknowledgement of digital storytelling as a genre in its own right has led to increasing attention being given to ethical considerations in relation to digital storytelling. The issues are complex and multi-faceted, ranging from storyteller consent through to use of other people’s images and music and the particular sensitivities of using personal pictures that might reveal identity when this could prove to be dangerous. A set of ethical guidelines for use in digital storytelling has been developed by StoryCenter (Gubrium, Hill & Harding, 2012) and addresses issues including: storytellers’ rights; consent, approval and release; confidentiality, anonymity vs having a voice; informed consent; editing and editorial control; support (for storytellers). These guidelines have developed into a code of practice and storytellers’ bill of rights and inform the practice of many digital storytelling facilitators around the world (CDS, 2013). Subsequent work by Hill, Harding and Flicker has delved more deeply into the increasing complexity of issues in relation to digital storytelling in the field of public health and has developed in parallel to the work of the Patient Voices Programme particularly in relation to an ethical, staged release process and sensitivities around release of highly personal stories to a worldwide audience (Gubrium, Hill & Flicker, 2014).

Digital storytelling in healthcare was pioneered by the Patient Voices Programme, with the first stories created in 2003 for the UK National Health Service’s Modernisation Agency. With these first Patient Voices stories arose some important ethical issues, and a number of questions presented themselves:

Common to all ethical processes is the protection of participants in any activity that might be deemed to be potentially harmful, as is the case in much bio-medical research. The challenges of how best to protect people who are willing to contribute to the improvement of healthcare have been addressed by many, but the work of Beauchamp and Childress has been particularly useful in the field of biomedical ethics. In keeping with most codes of research practice that are underpinned by principles of respect, justice and beneficence, their four principles are: respect for autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice, plus concern for the scope of application (Beauchamp & Childress, 2009). Their work has made a significant contribution to what has been referred to as ‘procedural’ ethics (Guillemin & Gillam, 2004), that is, the need for codes of ethics, research ethics committees, informed consent, etc.

However necessary these research processes are in the design and conduct of research, they are not sufficient when it comes to addressing those everyday challenges and dilemmas facing researchers for which there are rarely simple solutions. For these, it is also necessary to have what Guillemin and Gillam refer to as ‘practice ethics’ (2004). This notion of practice ethics relies on reflexivity and ‘ethical mindfulness’ (Guillemin & Heggen, 2009). Ethical mindfulness seems to be an expansion of the conventional notion of reflexivity, relying on vigilant attention to: ethically important moments; understanding and acknowledging the ethical importance of feelings (such as a sense of discomfort); the ability to articulate what is ethically important; the ability to be reflexive; and, finally, courage, particularly in relation to thinking about ethics in new ways and being willing to stand up to established structures if these seem inappropriate (Guillemin & Heggen, 2009). These ‘practice ethics’ and especially ethical mindfulness, are characteristic of the way we have approached ethical issues arising in our Patient Voices work.

Although anonymity does not appear in Beauchamp and Childress’ principles, conventional ethics approaches assume and assure both anonymity and confidentiality. However, not everyone wants to be anonymised; or, as one eloquent patient put it ‘I wanted to matter’ (Tilby, 2007). It was no surprise, therefore, when the first Patient Voices storytellers made it clear that they wanted to be acknowledged for their stories.

It was essential to the values and the success of the Patient Voices Programme that participants felt safe, valued and cared for and that a rigorous ethical approach should underpin the Programme’s activities.

In addition to the more obvious considerations highlighted above, and in view of the particularly difficult content inherent in many patient stories, consideration has also been given to the potential for digital storytelling to be therapeutic and the consequent need for supervision for facilitators (Hardy, 2012). While these are important factors to consider in relation the safety of storytellers, they are outside the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, although our work was not medical in nature, we wished to adhere to the Hippocratic principle of ‘doing no harm’, either to our participant/storytellers or ourselves.

The rest of this paper looks at how these issues were addressed, focusing on the experience of developing an ethical process that would be suitable for digital storytelling in healthcare: a process of trial and error, reflection and reflexivity, care and carefulness, learning from experience, mindfulness, and, always, striving to respect and protect everyone involved in the digital storytelling process.

The serendipitous discovery of a digital story by the author of this paper led to the decision to adapt the methodology for use in healthcare. Initially, the intention was to incorporate this visual media into the United Kingdom Health Education Partnership (UKHEP) e-learning programme as a means of prompting reflection and consideration of the ‘why’ of healthcare rather than simply the ‘how’. At a time when the importance of involving patients, carers and service users in the design and delivery of healthcare was just beginning to be acknowledged, we also believed that digital stories created by service users and carers would offer a uniquely affective way to help NHS Board teams understand patients and carers’ experiences of healthcare. (P Hardy & T Sumner, 2014).

Thus, in 2003, the Patient Voices Programme was founded. It was one of the earliest digital storytelling projects in the UK (BBC’s Capture Wales was established in 2001) and the first digital storytelling project in the world to focus specifically on healthcare. Without knowing of the existence of CDS, the Patient Voices journey began with little guidance but a great deal of passion and a determination to uphold values and principles honed during many years spent in adult education, quality control, counselling and facilitation and, more recently, healthcare service improvement.

In consideration of the best way to ensure safety and protection as well as acknowledging and valuing the contribution of people who have been willing to share their experiences in the form of stories, the Patient Voices Programme has adhered, as far as possible, to the four ethical principles outlined above. Indeed, these principles lie at the heart of the Patient Voices ethical process (Beauchamp & Childress, 2009;Hardy & Sumner, 2008).

The use of patient stories in healthcare education and service improvement is a relatively recent phenomenon. In the early years of the 21st century, stories, if they were mentioned at all, were consigned to the bottom of the hierarchy of acceptable evidence (Evans, 2003). This phenomenon is readily understandable when set against the backdrop of the drive towards evidence based medicine (EBM) in the 1990s: excellent research and evidence, such as that conveyed via Cochrane reviews (www.cochrane.org), were necessary in order to ensure the most effective and appropriate clinical decisions. However, what was lacking was the evidence of experience.

In an attempt to provide some balance for evidence-based medicine, a small group of clinicians-cum- academics developed what they termed ‘Narrative Based Medicine’ (Charon & Montello, 2002; Greenhalgh, 1999; Hurwitz, Greenhalgh & Skultans, 2004), highlighting the use of literature and patient stories to illuminate the subjective, human experience of those receiving healthcare.

Despite this intention to foreground the patient experience, somewhat paradoxically, patient stories, (often referred to as ‘anecdotes’), were considered to be fair game for cutting up and placing in categories, themes and sub-themes for analysis (Tilley, 1995), in much the same way as researchers might work with responses from a research questionnaire. While this is not an unknown phenomenon in qualitative research, it can change the meaning of a story according to the interpretation and needs of the researcher. Indeed, Hawkins and Lindsay (Hawkins & Lindsay, 2006) refer to this process as ‘dismemberment’, suggesting that ‘to treat stories in this way is to fail to respect the tellers of these stories. It is to make the assumption that our interpretation of the patient’s experience is more valid than their telling of it.’ This approach risks demeaning both stories and storytellers and represents a significant ethical hurdle. One possible response to this problem is to work closely with the people who are telling their stories to consider carefully exactly what they want to say, and how they want to say it, as is the practice in many digital storytelling projects, including Patient Voices.

Debate about whether to use the word ‘story’ or ‘narrative’ presents another hurdle to the world of healthcare education and research. The term ‘narrative’ tends to be more widely used in academic circles, while ‘story’ has attracted a somewhat pejorative association with a less serious account, even a fabrication. Narrative is often regarded as a factual account, while story can be thought of as more ‘reflective, creative and value-laden, usually revealing something important about the human condition’(Haigh & Hardy, 2011).

Another entrenched assumption in the world of healthcare education and research was that all patients (and others) willing to share their experiences and stories wished to remain anonymous and, therefore, unacknowledged. While affording protection and, in some cases, safety, and therefore enshrined in any respectable ethical process, this assumption does not allow for those who wish to be connected with their stories. It must be acknowledged here that ethical guidelines for medical and healthcare research were, by and large, developed for use in clinical trials where anonymity and confidentiality might be more desirable, but the fact remains that, should an individual wish to be acknowledged, it could be difficult for his or her desire to be fulfilled.

Greenhalgh, an early proponent of patient stories, does shift her position over time from one in which stories are referred to as ‘narratives’ and considered within the context of research, and therefore subject to conventional research ethics guidelines (T. Greenhalgh & Hurwitz, 1999), to a position where she acknowledges the importance of ‘story’ and even goes so far as to suggest that different forms of ethical approval might usefully be considered in situations where patients are sharing their stories (Trisha Greenhalgh, 2006).

In 2002, the UK Department of Health published Shifting the balance of power, expressing the aspiration that patients and carers should be at the very heart of healthcare and, furthermore, that they should have ‘choice, voice and control’ over what happened to them (DH, 2002).

Within a year of that report, the UK Health Education Partnership (UKHEP) had commissioned the development of an innovative e-learning programme clinical governance and challenged Pilgrim Projects, a small, bespoke education consultancy specialising in healthcare quality improvement, to incorporate ‘the patient voice’. At about the same time, a research project into the strategic leadership of clinical governance revealed that NHS Board teams were lacking an understanding of the patient experience (Stanton, 2004).

‘I am tired of telling my story to researchers and others who take my story, use only the bits that are helpful to them and leave the rest. They get their publications and their PhDs and I remain unacknowledged, anonymous and living on benefits.’

‘I don’t want to be anonymous. I don’t want my story to be “dismembered” taking only the bits that someone else considers useful. If I share my story, I want to be acknowledged and I want it to be told in my own words.’

‘Why should other people profit from MY story?

These were the words of the first two people who shared their stories with the newly-formed Patient Voices Programme, referring to their past experiences with researchers and others interested in their stories. In 2003, digital storytelling itself was still relatively young, if not quite in its infancy. It was unheard of in healthcare.

It was a stroke of great good fortune that the first two Patient Voices storytellers were both lawyers. Ian Kramer was an ‘expert’ patient called, who was HIV positive and also had a bipolar disorder; Monica Clarke was an ‘expert’ carer who had cared for her husband for 11 years following a severe stroke that left him permanently incapacitated. Both were involved in the Expert Patient Programme (EPP).

Funding from the UK NHS Modernisation Agency’s Clinical Governance Support Team made it possible for Monica and Ian to develop stories with the Patient Voices Programme. Their stories were intended to reveal their felt experiences of the values of clinical governance, that is: trust, equity, justice and respect (Stanton, 2004).

The prompt for those early stories were those very values identified above: ‘tell us a story’, we encouraged, ‘about trust. Or respect. Or justice.’ And so they did. Their stories are a testament to their courage and remain among the most popular stories still shown in schools of healthcare and medicine around the world. They can be seen at www.patientvoices.org.uk/ikramer.htm and www.patientvoices.org.uk/mclarke.htm

From the very beginning, it was important to ensure that both storytellers and their stories were safe. There was a strong sense that, if people were going to entrust their precious stories to the Patient Voices Programme, it was necessary to acknowledge the role of ‘guardians’ of the stories. Monica Clarke told us, in her inimitable way, that she was tired of other people ‘taking’ her story, sometimes misquoting it, sometimes taking things out of context, and using her story to further their own careers in research or education or quality improvement, gaining masters degrees and PhDs on the back of her story, always careful to guard her anonymity. ‘I don’t want to be anonymous anymore’, she said. These are my stories. I want to be heard and I want to be acknowledged’ (Hardy & Sumner, 2014)

Having listened to Monica’s concerns, one of the first principles of the Patient Voices Programme was not to presume that storytellers wished to remain anonymous. They would be acknowledged if they so wished. With their permission, storytellers’ names would appear on their stories. Another key principle was that, once approved by the storyteller, the story would not be changed. Working closely with storytellers to ensure that the story is really what they want to say (and not simply what we want to hear) offers rewarding opportunities for co-production and understanding.

Although our process has changed somewhat since those early days, it is still underpinned by the same principles and the intention of any changes has been to make the process more robust. In addition, there is every reason to believe that involving storytellers at every stage of the development of their stories, seeking their advice, guidance and approval before moving on, were successful in empowering storytellers and giving them as much control as possible over their finished stories.

From the earliest days of the Patient Voices Programme, there was a commitment to ensuring that every storyteller understood what the process of creating a digital story involved so that informed decisions could be made as to whether or not to participate in a digital storytelling workshop. With the help of Ian and Monica, the two lawyer-storytellers, a simple, one-page Protocol and Consent form was created, highlighting the values of respect, equity, trust and justice. This form set out the rights of storytellers, in terms of what they could expect from the Patient Voices Programme. Storytellers were assured that, once they had completed and approved a story, it would not be changed, thus preserving the integrity of the story and validating their own judgement as to how the story should be told and when it was deemed to be finished. The Protocol also explained that Pilgrim Projects would hold the copyright to their stories, so that the stories could be given away rather than sold.

Finally, it was made clear that the intention of the Patient Voices Programme was that the stories should be used for the purposes of healthcare education and quality improvement.

These early agreements were tested with the first storytellers. Ian and Monica had much to teach the Programme about assumptions. Not everyone can read well, not everyone can see well; not everyone can understand well. Not wishing to intimidate storytellers, nor to increase paperwork and bureaucracy unnecessarily, every attempt was made to minimise legal (and other!) jargon, to keep the forms as short and simple as possible, while still providing protection for everyone concerned, but primarily storytellers. Consent forms were also made available in large print format and, in acknowledgement of those who find reading difficult, a member of the Patient Voices team always explains the content and intention of the forms before asking storytellers to sign.

In the early days of the Programme, most of the video production work was carried out by Patient Voices staff, once storytellers had recorded their story and selected images. Realising that our editorial judgements might not be those of the storytellers, it did not seem appropriate for their initial consent to cover release of their stories without a further opportunity for them to be involved.

In an attempt to mitigate this situation and to ensure that storytellers had as much say as possible over their final digital story, they were invited to review and comment at each editing stage. Only when they were completely happy with every aspect of the story would it be released.

Over the first few years of the Programme, this Protocol and Consent form was refined, although it is still very recognisable. Gradually it grew into a two-stage Consent and Release process. The first stage was simply to consent to participate in a Patient Voices workshop. The second stage was to approve release of the story, once post-production work had been carried out.

As our process was itself refined and with the benefit of training in digital storytelling facilitation by the Center for Digital Storytelling, storytellers were encouraged to take over as much of the production process as they wished.

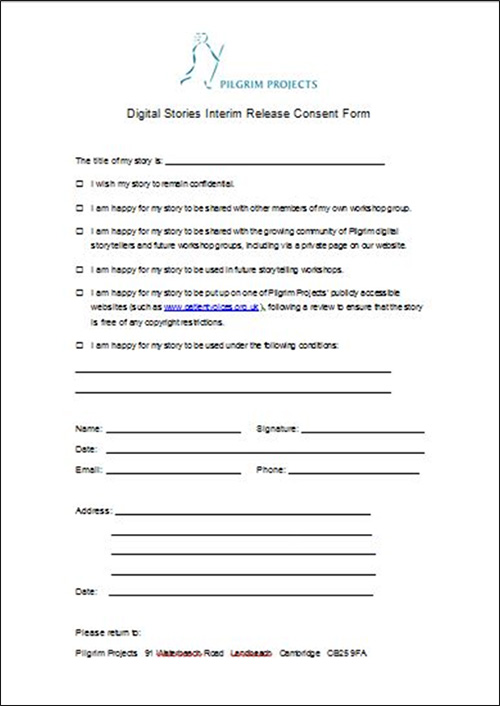

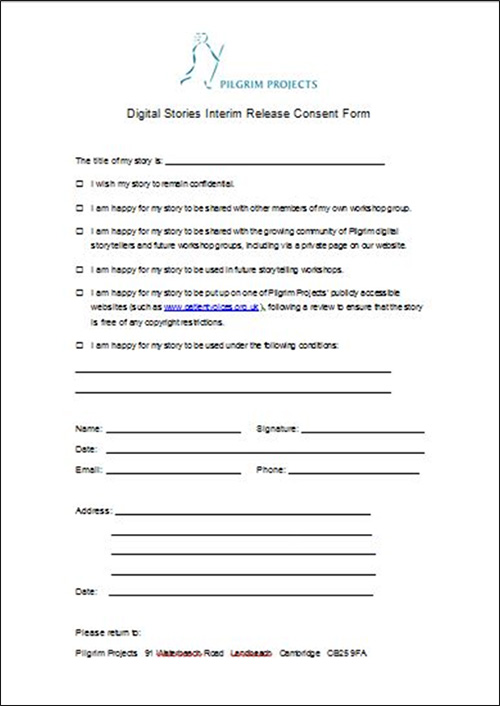

In time, the two-stage process became a three-stage process, with the introduction of an ‘interim release form’. This second stage took place after a draft of the story had been produced by the storyteller, and allowed time for review and reflection after the excitement of a digital storytelling workshop before agreeing to a final release. The interim release form allowed for several different levels of release so that storytellers could determine what Beauchamp and Childress referred to as ‘the scope of influence’ of their work (Beauchamp & Childress, 2009). The levels of release can be seen in Figure 1.

The interim release form also allowed Patient Voices staff to carry out post-production work on the stories. Storytellers were encouraged to watch and reflect on the story and show it to others; Patient Voices staff undertook to make any reasonable changes. Only when the storyteller was happy that the story accurately reflected their wishes and intentions were they invited to sign a final release form, triggering release of their story to the Patient Voices website under a Creative Commons (Non-commercial, attribution, no derivatives licence), thus making it publicly viewable. The opportunity for reflection and the lack of pressure to release a story has been an important part of the process.

Validation for the process, and the thought that has gone into it, has come from a number of places, including several universities, who have asked to use our forms, the Royal College of Nursing, the BBC and the National Audit Office.

As the years have passed, this process of informed consent has developed to include face-to-face and video briefing sessions, pre-workshop mailings and, where possible and practicable, pre-workshop phone calls. ‘Veteran’ storytellers are always invited to participate in these events, so that they can share their experiences with others.

The Patient Voices consent and release forms are appended to this paper.

Figure 1: Patient Voices Interim release form

Around the same time as the creation of the first Patient Voices stories, Creative Commons licensing came into being, initially in the United States. There are a number of difference licences but one covered our needs precisely, that is CC Attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives.

This licence ensured that both storytellers and the Patient Voices Programme would be acknowledged; it prohibited the sale of the stories and it ensured that no changes would be made to the story.

It must be remembered that the Patient Voices Programme began before the advent of YouTube, Facebook, Twitter and other social media and sharing sites. Limitations in bandwidth meant that video sharing was rare. However, the Programme’s intention was to preserve these precious stories and save them from the fate that had befallen many other learning programmes when the organisation who had commissioned the work was subject to a merger or worse, dissolution and/or extinction. Such was the fate of the Clinical Governance Support Team: if the Patient Voices stories had been hosted there, they would no longer be available for public use.

Creative Commons licences have changed and developed since their introduction in 2002, to reflect the growth of video and image sharing sites as well as the changing culture that promotes open access to much information in a range of formats and media.

Since the earliest days of the Patient Voices Programme, issues of ownership have been near the forefront of our minds. Our desire to protect storytellers and their work was one of the founding principles of the programme and one that was fraught with challenges and paradoxes. Although it is outside the scope of this paper to enter into the complexities of intellectual property, it is important to have a general understanding of the principles.

Intellectual property relates to a unique creation, such as a book, a photograph, a movie or a digital story. Intellectual property rights vary from legal jurisdiction to legal jurisdiction. Within the United Kingdom, intellectual property is regarded as being of the following types:

More information may be found here: https://www.gov.uk/intellectual-property-an-overview

In the early days of the Patient Voices Programme, it was not uncommon for sponsoring organisations to want to have control over the stories that were being created, to ensure that ‘their’ stories were conveying messages that were acceptable to the organisation. Since this directly contradicted the intention of the Patient Voices Programme, which was to reveal the lived experiences of healthcare precisely so that important lessons could be learned, some lively discussions ensued.

Following some of these early discussions that focused on control, copyright, ownership, use of logos and, importantly, who was to approve release of the stories, we engaged a lawyer who assured us that our process and forms were acceptable and watertight. We held firm on the approval process (insisting that it was the storyteller and only the storyteller who could approve release of the story) and developed an agreement with sponsoring organisations that, while it was not always possible to control the stories that would emerge, it was possible to ensure that that no stories were libellous by gently guiding storytellers away from potentially contentious accusations or unwanted identification, either in words or pictures. In addition, as part of the initial consent process, storytellers are asked to confirm that they have permission from anyone identifiable in their photos.

Issues of ownership are taken very seriously, with one of the guiding principles of the Programme being not to ‘take that which is not freely given’ with respect to images and music, just as with stories (Hardy & Sumner, 2008).

In an attempt to protect both storytellers and the Programme, storytellers are steered away from Google images and free music websites, whose licences are as punitive for misuse as they are lengthy and impenetrable. Thus an extensive library of royalty-free images has grown over the years, with the purchase of licences to use images from image libraries, which is used to augment storytellers’ own collections of pictures. Insistence on the use of music with no copyright restrictions has resulted in the commissioning of a number of royalty-free pieces and the purchase of licences to use existing royalty-free music.

This process has altered little in the past few years and there remains an uncompromising adherence to these principles: that no storyteller should use an image or a poem or a piece of music that is someone else’s copyright (unless permission can be obtained to do so); that the stories will not be sold; that storytellers who wish it will be fully acknowledged; that anyone else who contributes to the story (including musicians and sponsoring institutions) will also be acknowledged.

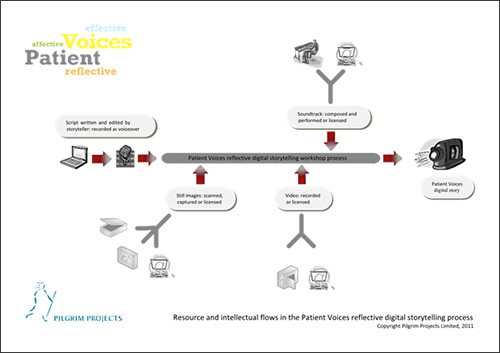

We have attempted to represent the complex flow of copyright and ownership in Figure 1, with an accompanying explanation.

Figure 2: Resource and intellectual flows in the Patient Voices digital storytelling process

The story itself is the creation, and hence intellectual property, of the storyteller. It is protected by copyright law.

Many of the images or video clips used in the story belong to the storyteller. Some images may belong to Pilgrim Projects Limited, while still others are stock images licensed from photo libraries such as iStock.

Soundtrack files, such as music, sound effects, etc. are either selected by the storyteller from a library of music licensed by Pilgrim Projects from a variety of sources; music may also commission pieces to be composed and recorded specifically for a particular story.

Approved stories are released into the Patient Voices Programme under a Creative Commons Licence, with the copyright retained by Pilgrim Projects.

The decision not to put Patient Voices stories on YouTube (when it came along in 2005) has been a carefully considered one that has almost certainly been at the Programme’s expense. The licensing conditions imposed by YouTube (YouTube, 2010) conflict with the licence under which Patient Voices stories are released, as well as our agreement with storytellers, that is, that their stories would not be changed or sold and that they would be appropriately attributed.

Even with the best of intentions, the most thorough of briefings, the most careful explanations, the most earnest attempts to ensure that storytellers are happy with their stories, circumstances change and it has been necessary to respond appropriately to these changes.

Two short case studies serve to illustrate some of the complexities support the decision for consent to be viewed as a process rather than an event.

The first case study illustrates the softening effect that time may have on a storyteller’s decision about whether or not to release a story.

The value of time to reflect

C made a more personal story than she had planned or anticipated. With the support of the others in her workshop group, she was encouraged to find a more meaningful story and, in this process, she also gained some insight into the impact of some childhood experiences on her later life.

Prominent in her field, C decided, at Interim release stage, not to let her story go any further. It was duly archived.

A conversation some years later resulted in a different decision. Realising that others might benefit from seeing her story, and from the recognition that, unless people in positions such as hers are prepared to share their stories, it is likely to be difficult for others to do so, she decided to sign a final release form and release her story publicly.

Had the process consisted of only one, or even two, stages, this change of heart would not have been possible.

The second case study illustrates another important aspect of the three-stage consent and release process, i.e. that it is possible to withdraw (either consent or participation) from the process at any time.

Safeguarding storytellers

Several women who had taken part in a local health promotion programme all made stories that focused on domestic abuse. They understood the aims of the workshop and the intention of the Patient Voices Programme and signed initial consent forms. Discussions in the workshop considered the use of imagery that would ensure the storytellers’ anonymity. It was essential that their identity not be revealed in the stories for fear of further abuse but they wanted to describe their learning from the programme they had participated in, and talk about the courage they had gained and the skills they acquired to look after themselves.

Post-production work concentrated on finding metaphorical images (clouds, skies, plants, etc.) to accompany their voiceovers about the details of the abuse they had suffered. No names were to be used in the stories; these stories would definitely be anonymous.

The draft stories were shown to the storytellers but, in each case, they decided that it was too risky to release the stories. The stories have never been released.

In the above case, the stories were never released. Although it is rare, once released, for a story to be removed from the website, there have been two or three requests in the past 12 years for stories to be removed. Usually the reason given is in relation to a divorce. Naturally, these requests are always met.

The development of an ethical consent and release process that does as little harm as possible is complex and multi-faceted, especially when balanced with the attempt to ensure that voices that are often silenced can be heard so that important lessons can be learned. The potential for good that is afforded by making personal stories of healthcare widely available via the internet must be seen alongside the potential for harm to storytellers and their families. Careful consideration must be given as to how best to protect everyone involved in the digital storytelling process while also honouring the voices of those who would be heard.

This explanation of how the Patient Voices Programme has striven to develop such a process also offers some insight into the challenges of working within an ethical context that extends beyond the digital storytelling workshop and reveals an understanding of consent as a process rather than an event, protecting and respecting all those who generously share their stories to improve the world of healthcare.

Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (2009). Principles of biomedical ethics (6th ed. ed.). New York ; Oxford: Oxford University Press.

CDS. (2013). Ethical practice in digital storytelling. Retrieved from http://storycenter.org/ethical-practice/

Charon, R., & Montello, M. (2002). Stories Matter: The Role of Narrative in Medical Ethics (Reflective Bioethics): Routledge.

DH. (2002). Shifting the balance of power : the next streps. London: Department of Health, Great Britain, .

Evans, D. (2003). Hierarchy of evidence: a framework for ranking evidence evaluating healthcare interventions. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12(1), 77-84.

Freire, P. (1973). Education for critical consciousness (Vol. 1): Continuum.

Greenhalgh, T. (1999). Narrative based medicine: narrative based medicine in an evidence based world. BMJ, 318(7179), 323-325. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9924065

Greenhalgh, T. (2006). What Seems to Be the Trouble?: Stories in Illness and Healthcare (1 ed.): Radcliffe Publishing.

Greenhalgh, T., & Hurwitz, B. (1999). Narrative based medicine: why study narrative? BMJ, 318(7175), 48-50. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9872892

Gubrium, A., Hill, A. L., & Harding, L. (2012). Digital Storytelling Guidelines for Ethical Practice, including Digital Storyteller's Bill of Rights. Retrieved from https://www.storycenter.org/s/Ethics.pdf

Gubrium, A. C., Hill, A. L., & Flicker, S. (2014). A Situated Practice of Ethics for Participatory Visual and Digital Methods in Public Health Research and Practice: A Focus on Digital Storytelling. American Journal of Public Health, e1-e9. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301310

Guillemin, M., & Gillam, L. (2004). Ethics, reflexivity, and “ethically important moments” in research. Qualitative inquiry, 10(2), 261-280.

Guillemin, M., & Heggen, K. (2009). Rapport and respect: negotiating ethical relations between researcher and participant. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 12(3), 291-299.

Haigh, C., & Hardy, P. (2011). Tell me a story—a conceptual exploration of storytelling in healthcare education. Nurse Education Today, 31(4), 408-411.

Hardy, P. (2012). Using stories: making the big picture personal: a presentation to Alberta Health Services. Cambridge: Pilgrim Projects.

Hardy, P., & Sumner, T. (2008). Digital storytelling in health and social care: touching hearts and bridging the emotional, physical and digital divide. Lapidus Journal(June 2008).

Hardy, P., & Sumner, T. (2014). Cultivating compassion: how digital storytelling is transforming healthcare. Chichester: Kingsham Press.

Hardy, P., & Sumner, T. (2014). The journey begins. In P. Hardy & T. Sumner (Eds.), Cultivating compassion: how digital storytelling is transforming healthcare. Chichester: Kingsham Press.

Hawkins, J., & Lindsay, E. (2006). We listen but do we hear? The importance of patient stories. Wound Care, 11(9), S6-14.

Hurwitz, B., Greenhalgh, T., & Skultans, V. (2004). Narrative research in health and illness. Malden, Mass. ; Oxford: BMJ Books.

Illich, I. (1973). Tools for conviviality.

Lambert, J. (2002). Digital storytelling : capturing lives, creating community (1st ed.). Berkeley, CA: Digital Diner Press.

Stanton, P. (2004). The Strategic Leadership of Clinical Governance in PCTs: NHS Modernisation Agency.

Tilby, A. (Writer). (2007). Thought for the day [Radio broadcast], Thought for the day. UK: BBC.

Tilley, S. (1995). Accounts, accounting and accountability in psychiatric nursing. In W. R (Ed.), Accountability In Nursing Practice. London: Chapman Hall.

YouTube. (2010). Terms of Service. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/t/terms

Appendix I: Original Patient Voices Protocol for Storytellers

Storytellers and their stories will be treated with respect at all times. We will try to interpret accurately the intentions of the storyteller and to preserve the integrity of the story. We will always try to be flexible and sensitive to the needs of storytellers with regard to the place and pace of recording.

ConsentWe will not record a story unless we have prior informed and valid written consent from storytellers; we will provide whatever information is necessary about the process and the existing stories to enable such consent to be given.

Storytellers will be asked to sign consent form agreeing to the use of the final version of the story as an educational and learning resource intended to improve the quality and responsiveness of services for patients and carers.

CopyrightFinal control over what is included in the digital story will rest with the storyteller. A ‘first cut’ will be sent for comment and a ‘final version’ will be sent for the storyteller’s approval before the story is used elsewhere.

Copyright will rest with the National Health Service (but consent will not be withheld for reasonable use of the stories by the storyteller).

SupportStorytellers will be offered emotional support during and after telling their stories. Many storytellers have commented on the therapeutic benefits of telling their stories in this way.

ReimbursementStorytellers will be repaid for expenses incurred in the recording of their story (including, where appropriate, reimbursement for respite care for people for whom they normally care).

© 2004 Pilgrim Projects Limited

Appendix 2: Patient Voices Protocol for Storytellers 2012

Appendix 3: Patient Voices interim consent form

Appendix 4: Patient Voices final release approval