Department of Educational Research

University of Graz, Austria

Email: clemens.wieser@uni-graz.at

Knowledge transformation drives changes in teaching practice. It takes place when a teacher mobilises personal knowledge for teaching. Technology can inform research on how knowledge transforms in practices of distancing from classroom teaching, and how a teacher draws on them to engage with a class. The paper introduces three fieldwork approaches that blend ethnographic fieldwork with technological possibilities: (1) Videographies of classroom interaction document practical educational knowledge of teachers and the orientations they use in classroom interaction. (2) Stimulated recall allows teachers to re-view classroom interaction. In talking about what has happened, teachers can present rationalisations of classroom events and explain how they addressed these events. Stimulated recalls also allow teachers to construct narratives in which they detail lived teaching experiences. Both stimulated recall and narratives document personal educational knowledge of teachers. (3) Video diaries allow teachers to tell stories from places outside of school, places in which they think about teaching and prepare for classes. There, teachers operate with self-technologies that scaffold the transformation of personal knowledge into practical knowledge. A conclusion outlines how data from these three technology-enhanced fields can be integrally analysed.

Keywords: educational technology, ethnography, videographies, transformative practices

Knowledge transformation is what drives change in teaching practice. A teacher transforms her knowledge to perform in a specific classroom, to interact with a specific group of students, and within a specific school environment. Knowledge transformation is “a journey with stages and milestones for coming closer [and] maintaining a distance to the context” (Borgnakke, 2015, p.6), and results in teaching that remains adaptive to a specific situated context. This adaptiveness relies not only on personal educational knowledge, but also on practical educational knowledge of teachers. Both modes of knowledge consequently should reflect in fieldwork on knowledge transformation. Outlines of both personal and practical educational knowledge strengthen the focus of fieldwork strategies and enable us to determine how personal technologies can enhance classic ethnographic fieldwork.

Practical educational knowledge is situated. It is a mode of knowledge in which a teacher does not need to solve problems or make decisions because “he knew what he was then doing, not in the sense that he had to dilute his consideration of his premises with other acts of considering his consideration of them” (Ryle, 2009, p.158). Practical educational knowledge thus informs a teacher to perform in class. Situated classroom performances of an experienced teacher strike us because we are able to observe a professional who virtuously handles a complex situation. A teacher handles this complex situation in order to create a context that facilitates learning, to constrain activities that divert the focus from learning, and to shield learners “against the chaos and inflexible demands of ‘reality’” (Saugstad, 2005, p.359). In teaching, a teacher immerses in skillful activity, sees immediately how to achieve a goal, and is able to make subtle and refined situational discriminations. Through discrimination, in the original sense of the word discriminatio (Foucault, 2005, p.131), a teacher separates the content of an event from subjective orientations on which she would habitually rely to create order classroom interaction. These discriminations enable a teacher to mark a “division between that which does not depend on us and that which does (Foucault, 1986, p.64), and distinguish situations that require one reaction from those that demand another. In order to perform, teachers rely on a set of orientations that guides their attention while teaching. These orientation patterns shape not only through continuous teaching practice. Teaching also draws on personal educational knowledge, knowledge that is likely mobilised by a teacher to maintain performance, to interpret classroom events, and to react to them. Even though we can observe virtuous teacher performances immediately, it remains difficult to pinpoint the personal educational knowledge a teacher draws on.

Personal educational knowledge resides in cognitive structures, forms subjective theories, and enables a teacher to reflect upon classroom interaction and events. These reflections modify both how a teacher conceives teaching, as well as the orientations for teaching themselves. Personal educational knowledge consequently incorporates strategies for teaching as well as strategies for reflection. How personal educational knowledge of teachers is structured and used in and out of teaching has been an ongoing topic of educational research. However, empirical research yet struggles to illustrate patterns in which personal educational knowledge is mobilised for teaching. An illustration of such patterns requires fieldwork to focus on practices of distancing from classroom interaction, and see how teachers relate to teaching in reflection and in planning. Thus, orientations for teaching continually transform by moving in and out of teaching to adapt to a specific class context. Empirical fieldwork can trace these transformations. Fieldwork on classroom interaction may employ videography to enable us to systematically review and analyse situated practice and reconstruct practical orientations. Fieldwork that follows personal practices in which a teacher distances herself from classroom and thinks about events may reach out to personal technologies, and these technologies can support fieldwork and enable us to make sense of how a teacher scaffolds teaching in reflection.

The distinction of personal and practical educational knowledge outlined here puts two kinds of practices into the focus of fieldwork on knowledge transformation: On the one side, fieldwork should attend to practices of involvement of teachers and practical educational knowledge in classroom interaction. On the other side, fieldwork should attend to practices of detachment and reflective educational knowing embedded in teacher narratives. Both fieldwork domains document figurations of knowledge transformation. The subsequent main body of this article gives an outline of these domains and explores technological possibilities for fieldwork on knowledge transformations.

The fieldwork domains outlined could result in fields expanded through classical ethnographic fieldwork. Classical ethnographic fieldwork can be characterised by direct involvement and long-term engagement of a researcher in the field, continual long-term data collection and strong reliance on participant observation, and participation in the everyday life of people (Hammersley & Atkinson, 2007). Ethnographic fieldwork deliberately “involves some degree of direct participation and observation”, and constitutes a distinctive way of situated understanding of social activity (Atkinson, 2015, p.4). Direct participation and observation are personal technologies used by a researcher to develop situated understandings. However, direct participation and subsequent field notes and considerations entail situated attention and discrimination and might lead to unwanted bias. This is one reason to use technological tools into fieldwork strategies: Technology allows video and audio recordings, which were largely unavailable during the initial development of ethnographic fieldwork strategies. Audio and video recording tools enrich the construction of a data set, and one data set may now include field notes as well as audio and video recordings and transcripts.

Technological possibilities complement classical ethnographic fieldwork and provide an augmented focus on practices of involved teaching and practices of detached reflection on teaching: Practices of involved teaching are what we can observe in class, and we can accompany observations with videographies to augment the situated attention of the researcher with video recordings that document teacher actions, statements and attentions. Practices of detached reflection on teaching become the focus in interviews in which we can involve with teachers who may then elaborate on their teaching. Videographies allow us to recall events together with teachers and enable them to revisit what happened. Fieldwork can also include video diaries, as video diaries can provide a bridge between the sphere of working at school and the sphere of working at home. While fieldwork on practices of involvement discretely link to the stage of classroom interactions, fieldwork that focuses on practices of detachment may encompass a broader array of stages. Each of these stages may provide different reflections in which teachers elaborate on their teaching and introduce orientations they draw on. The following sections explore possible stages of fieldwork, reflect on the fields established through them, point out knowledge documented within them, and locate it in the process of knowledge transformation.

Involved teaching in class relies on situated performance. Practical educational knowledge maintains this performance, and teachers draw on this practical knowledge continually to act in respect to the situation, events and student actions. A teacher cannot predict events due to the contingency of classroom interaction and the contexts in which this interaction takes place. Consequently, teachers learn to deal with insecurity and unpredictability and to act flexibly. Their ordering of interaction relies on practical educational knowledge, knowledge that Schön (1983; 1987) has called knowing and reflecting in action to highlight the procedural quality in which this knowledge operates in order to confront knowledge from previous experiences with a current context of action. The conception of practical knowledge developed by Schön hints to qualities of events we can look out for when doing participant observation in class: Knowing in action refers to the non-reflective mode in which professionals act when not confronted with unusual challenges. Reflection in action is vital when teachers manage teaching in challenging classroom situations that require more than intuitive acting: “By reflecting on the way we are performing it we may seek to establish rules for our own guidance in this act” (Polanyi, 1998, p.30). Reflection in action is characterised as episodic step back from the natural state of knowing because the situation requires additional attention. It takes place when routine patterns seem inappropriate to achieve a goal. An attempt to project order onto a situation leads to unexpected results, the situation “talks back” (Schön 1987, p.157) to the teacher and the teacher listens to the situation to restructure action. The process of reflection in action starts with an experience of surprise and confusion in respect to a tacit aspect of a situation and gives attention to situational peculiarities in order to comprehend this aspect and handle it. In the process of reflection in action, teacher do not separate aims and ways for teaching but set them up reciprocally to define a tacit aspect. When reflecting in action, a teacher does not resolve a situation by searching a rule appropriate for the situation and applying it: “The application of the criterion of appropriateness [of a rule] does not entail the occurrence of a process of considering this criterion“ (Ryle, 2009, p.20). Explicative assessment of an action as appropriate would require a teacher to reflect how to act professionally, which requires her to reflect the mode of reflection and enter regress. Reflection in action is immune to regress because it accommodates the singularity of a situated event and integrates subsidiary awareness into a focal awareness in order to experiment within in a situation. This awareness is directly fed back into action without interrupting the primary process of action, which indicates that reflection in action is not a process separate from action, but part of it “to free possible futures” (Geerinck, Masschelein & Simons, 2010, p.388). Reflection in action establishes a tentative framing of the situation and openness for situated responses. This post-critical perspective locates professionalism in the ability of a teacher to act within a personal framing, to break out of this framing, and to reframe the situation. Similarly, Bourdieu has emphasised that practical educational knowledge is a “kind of practical sense for what is to be done in a given situation” (1998, p.25) which scaffolds teacher practice because it allows teachers to handle classroom situations based on habitual acting. Expressions of that practical sense can be found in authentic classroom interactions that document situational attention and discriminations of teachers.

Participant observation enables a researcher to co-experience events and become sensitive to the implications of situated attention and action, and field notes enable researchers to document these observations. Classical ethnography argues that observations provide an entry point to comprehend “cultural formation and maintenance” (Walford, 2009, p.272) of teaching as a context for learning. They provide a resource for initial comprehension of educational knowing through “entering a classroom culture” (Putney & Frank, 2008, p.217). Thus, the effort to enter classroom culture by attendance and observation allows sensitisation to the emergence of orientations and shifts between knowing in action and reflecting in action. Initial comprehension and sensitisation will furthermore guide interviews to give credit for the “interdependence of various forms of knowledge transmission” and “transcend traditional boundaries” in data collection (Walford, 2007, p.153) in order to provide perspectives that stimulate teacher narratives on educational knowing. However, orientations for teaching tacitly guide attention, and these orientations are fundamentally distinct from practical educational knowledge. These orientations are documented in action, and videography can provide the means to revisit review and reconstruct orientations for teaching. Ethnographers originally intended “collecting naturally occurring discourse” and actions, which was “accomplished traditionally by listening and then later recalling in writing what was said, when, and to whom” (Markham, 2013, p.439). Being in the field, listening to participants, and experiencing events and interaction provide first-person experiences of forces within a field. These forces in a field are impossible to reconstruct from documents, as illustrated by Dreyfus, who gives an example of mastery in chess. Mastery itself can be read as a conception of practical knowledge: “To find out we need to learn more about the way the skill domain is experienced by a master involved in the game. In this connection, we can learn from [chess Grandmaster] Vladimir Nabokov. As Nabokov spells out brilliantly in The Defense, a chess master does not see the board as a propositional structure no matter how specific and contextual. When involved in the game, and only while involved, he sees ‘lines of force’” (Dreyfus 2007, p.106). This example illustrates the necessity of experience in the field, an argument backed by a conceptual consideration of Polanyi (1998, p.279): “We must accredit our own judgment as the paramount arbiter of all our intellectual performances”, as critical reasoning or ex-post data analysis underdetermines practice. Practitioners evidently believe more than they can prove, and know more than they can say. When we endorse this statement, we need to take a fiduciary approach to research: An experienced teacher can be trusted because she tacitly knows what she is doing, and similarly an ethnographer can be trusted because she knows what to look out for when doing participant observation. However, ethnographers can use videography to revisit and reread data of naturally occurring discourse, and reconstruct tacit orientations of teachers embedded in their action.

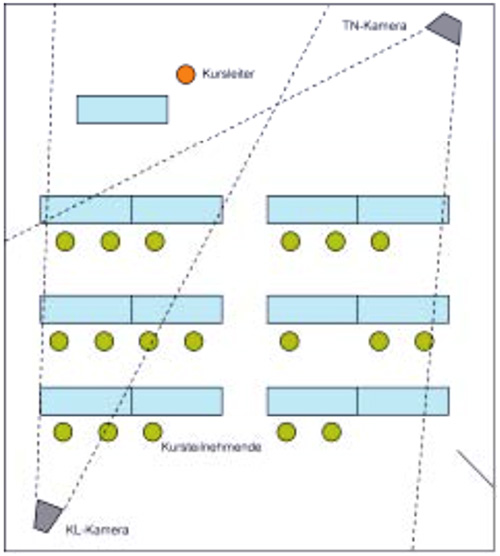

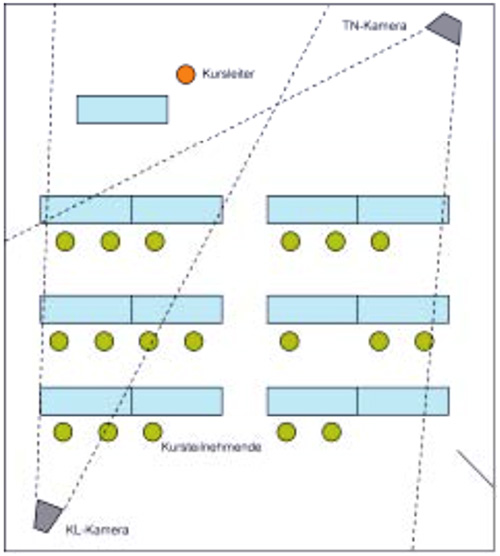

Fig. 1: Camcorder positions for two-perspective videography (Dinkelaker & Herrle 2009, p.25)

Videography provides data of authentic classroom interaction, conveys the synchronicity of actions and sequences of talk. Data collection with two camcorders set up at opposing corners of a classroom creates two perspectives on the classroom as a public sphere: One camcorder takes a frontal perspective on classroom interaction. This perspective is similar to the acting teacher perspective and documents student actions in class. A second camcorder at the back of the classroom records teacher actions (cf. Fig. 1). Camcorders can be set up before the start of a lesson to sustain a regular order of events, and furthermore include initial interactions in the recording. Intrusion into the field can be minimised when both camcorders are set up stationary, and when they are set up before the start of a lesson. Camcorders and researchers might generate situated bias and influence the teacher and student interaction, which is why researchers should attend classes over a longer period of time to familiarise participants with a setting of “seeing and being seen” (Mohn 2009, p.174). Videographies can also be a resource for stimulated recalls to re-view classroom events together with teachers.

Detached reflection on teaching reflects in stimulated recalls and narrative interviewing with teachers. Stimulated recall and interviewing both focus on the personal orientation framework for teaching, a framework that enables situated judgements of events in class. These personal orientations are documented in narrative attempts to order experience, and complement pragmatic attempts to order experience through practical orientation (Messmer 2015, p.8-9). Bruner (1986, p.11) also noted this complementarity in his elaboration on modes of thought, where he distinguished a narrative mode from a pragmatic mode: "There are (…) two modes of thought, each provides distinctive ways of ordering experience, of constructing reality. The two (though complementary) are irreducible to one another". Personal orientations for teaching are cultivated in detached reflection on teaching – this may include thinking about previous classroom events, discussing events and perspectives with others, or reading about teaching, i.e. an academic article on teaching and learning. While teacher orientations used tacitly in classroom interaction can be analysed with data from videographies, classroom interaction itself does not allow a teacher to comment on her actions and introduce reflections in which she perceives classroom events. Interviewing explores perceptions of events, since it provides communicative opportunity for a teacher to reflect on classroom events and actions. Such reflections provide time for a teacher to elaborate her understanding of an event, to reveal how she personally embeds an event within her horizon of orientations for teaching, and to explain how she delineates similarity and difference of events and experience in order to find an orientation appropriate for a specific classroom context. A teacher can articulate perceptions as a narration on classroom events that introduces plausible ex-post explanations of situated knowing, and these explanations introduce personal orientations that also point to situated practical orientations. Ex-post explications document the educational horizon in which a teacher reflects and the analytical skills that scaffold classroom practice.

Narrative interviews on classroom events elicit personal educational knowledge because narrations oblige a teacher to complete, condense and detail lived experiences. These obligations make narrative interviews “particularly relevant to studies of everyday information behavior” that aim to conceptualise and theorise everyday knowledge in practice (Bates, 2004, p.17). Narrative approaches to interviewing are based on the presupposition that stories reveal the perspective of the interviewee, because an interviewee will use personal spontaneous language in the narration of events in order to “reconstruct social events from the perspective of informants as directly as possible” (Jovchelovitch & Bauer, 2000, p.59). Narrations in personal spontaneous language preserve form and syntax native to the personal culture of teaching in which teaching practice takes place. These narrations also reflect personal patterns of knowledge, as well as acquired cultural norms of communication on teaching. Teachers narrate previously lived experiences that “enable us to make sense of the present“ (Watson, 2009, p.469), and refer to personal educational orientations for teaching. Narrations help us to overcome barriers that can arise in data collection on tacit practical as well as personal knowledge, because a narrative approach levels the communicative field and creates shared meanings between the researcher and participant who may have difficulty to respond to more formal and rigid questioning. Narrations provide a plot that reveals moral orientations, perceptions and motives for action in relation to classroom events, and thus are no mere lists of events, but an attempt to link events in time and meaning, perform ordering, and provide context for events, actions, and goals. With respect to the transformation of educational knowledge, narrative interviews provide the opportunity to ask teachers to recount unusual situations and events. These unusual situations and events are likely to induce a switch between knowing and reflecting in action, and elicit narrations of experiences in which a teacher switched one orientation for another one. However, narrative interviewing needs to provide flexibility to accommodate new aspects of events that may emerge in a teacher narrative and connect them to an actual event in class. Stimulated recall supports this connection.

Stimulated recall provides the possibility to revisit classroom events, look at videographies collected in class, and talk about them with the teacher. Recalling classroom events allows teachers to explore these events again, describe aspects that they found relevant with respect to this situation, and elaborate on them. Stimulated recall provides teachers with an „opportunity to discuss their strategies for interaction while they are directly confronted with recorded examples of themselves engaging in interactions“ (Dempsey, 2010, p.350). In stimulated recall, teachers may also revisit and discuss aspects that became relevant for the researcher in observations. Such a recall will, with respect to the conceptual difference of personal knowledge and practical knowledge, not result in an explication of the situated judgement that a teacher relies on in teaching, but much rather generate retrospections. Such retrospective narrations on situated perceptions and reflections do not reflect “objective social mechanisms” of events (Bourdieu 1998, p.97), but ex-post explanations of teacher perception and reflection. Retrospections provide differentiated descriptions of personal comprehension in situations, especially in professional fields that demand reflection on personal actions. Such ex-post explanations document personal knowledge of a teacher with respect to the process in which she compares experiences and events, considers relevant contexts, and eliminates alternatives in order to find a suitable orientation for a specific situation. The relevance of narrations in stimulated recall highlighted here underlines that a narrative approach to fieldwork may sensibly embed stimulated recall. Such narrative approaches explicitly abstain from prompts in questioning to prevent overly structured guidance in an interview, because too much guidance “may invite the subject [teacher] to match this with a restructured account”, which could result in the researcher missing relevant personal orientations (Lyle, 2003, p.873). A narrative approach allows teachers to participate in selection and control of additional resources to recall events, and this cooperative approach reinforces the explanatory structuring of teachers as interview partners, which will itself point to personal orientations for teaching. So, without a stimulated recall, interviews with teachers would only encompass events and strategies in the way that the teacher wants to talk about it. A review of events, actions and verbatim statements in class would be excluded, which would result in a retrospection with strong focus on the subjectivity of the teacher. Without embedding it in an elaborate narrative fieldwork strategy, stimulated recalls are in risk of strong structuring. This would jeopardise an opportunity for teachers to disclose personal knowledge, elaborate on contexts of interaction they consider as relevant, and outline strategies in which they performed ordering in a situation. In this respect, technology may support, but cannot replace, classical strategies for ethnographic fieldwork.

Reflection on teaching takes place in spaces within schools, and these reflections happen rather soon after teaching in a class – during a coffee break, in a chat with a colleague, or during a break in teaching. Interviews in schools capture teacher reflections soon after teaching, and provide an opportunity to sit down with a teacher and talk about their experience. Interviews offer a field that allows discussion of these experiences. However, teachers do not limit their reflection to interviews. Teacher reflection reaches far beyond their work in school, for example when working at home to follow up the previous lesson and prepare for the next one. Fieldwork can address teacher reflection out of school by opening up another field, and diaries are one opportunity to do so. The areas of fieldwork outlined this far are temporally and spatially restricted to the classroom and to school, where researchers conventionally do their recording and interviewing. Fieldwork in school provides data on involved performance. It also provides data on detached practice and reflection on action – but this data is limited, as reflection does not necessarily take place in schools. Reflection on classroom events and actions regularly take place when teachers are out of class and school, for instance when they are at home or at other places that provide an environment appropriate for reflection from a teacher perspective.

Video diaries give access to personal reflections that take place out of school. They shift attention to personal places of work and professional reflection, which allows for a new area of fieldwork. Researchers with experience in using video diaries report, “Fieldwork was no longer restricted by the time and space in which the researcher naturally could observe and interview”; they also report that video diaries gave participants “a chance to define what to disclose to the researcher – and when and where to do it” (Noer, 2014, p.86). Murray (2009, p.475) points to a potential benefit of using video diaries instead of traditional written diaries, since “the video contextualises in time and space”, and thus includes more context than a traditional written diary conveys. Video diaries permit participants to make their private practice public, which always includes acts of explanation and self-representation. Participants reveal how they manage and present their identity, and draw on their identity and self to reflect on and prepare for their teaching (Holliday, 2004, p.51). Participants also control how much they want to reveal, and the possibility of self-regulation provides benefits similar to that of narrative interviewing: It empowers the participant to frame experiences in a way that she finds relevant, and thus convey the personal orientations she draw on for practice. Similar to narrative interviewing, performances on video convey personal spontaneous language, and this personal spontaneous language reflects the personal knowledge and concepts of a teacher. Video diaries document reflection on action itself as situated practice, that is, technology allows us to record aspects of time and space in which teachers re-produce and alter their personal orientations for teaching. Video diaries thus indicate how a teacher shapes her personal knowledge in preparation for teaching, and reflects a part of the process of knowledge transformation.

Knowledge transformation reflects subjective reference acts to the context of classroom interaction and schooling, and both contexts lead to the “putting into place of a subject” (Butler, 1997, p.90). This conceptual framing of knowledge transformation points to some issues we can look out for in fieldwork: The teacher as a subject resists inconclusive threats for teaching that may arise from these contexts by drawing on both private experiences and public experiences. Teachers manage this resistance through “technologies of the self” (Foucault, 1988; 2005) that corrode dissociative interference and reject transformation of culture into commodity. Such “technologies of the self” maintain and order the orientations necessary to perform teaching. They also enable a teacher to align practice with personal educational aims. Educational aims point to the moral dimension of schooling, a morality that sets an ideal of effects personal educational practice should have. These educational aims of a teacher provide orientations for educational practice. A teacher accommodates such personal educational aims in reflection on action and aligns them with her situated action in class, a horizon that makes morality ubiquitous in the interactions between teachers and students. From a personal knowledge perspective, teachers do not incorporate morality and critical rationality in terms of abstract theoretical criticism, because practice cannot live up to “systematic forms of criticism” that can be employed in explicit reflection (Polanyi, 1998, p.278). Much rather, researchers may look for strategies in which teachers negotiate personal educational aims with their educational practice. Video diaries may contain traces of these strategies and may be analysed jointly with data from other areas of fieldwork to trace and illustrate the process of knowledge transformation.

Each area of fieldwork outlined above provides a unique field that documents a link between involved teaching and detached reflection. Orientations of teachers reflect in involved teaching, are maintained and transformed in detached reflection, and are organised in patterns that refer to specific challenges in teaching. An account of these orientation patterns may reveal three fundaments teachers draw on: (1) Resources that teachers use to perform teaching; (2) Strategies in which teachers maintain their teaching; and (3) how teaching takes place as dynamic adaption that is rooted in the teacher self that provides a personal horizon for teaching. Orientation patterns of teachers build coherence between the areas of fieldwork and allow for integrative analysis. However, drawing connections between fieldwork areas remains a challenge for research, and this is where ethnographic strategies can provide a key link.

Ethnographic data analysis may employ Documentary Method strategies to reconstruct orientation patterns for teaching. The Documentary Method was introduced to ethnomethodology by Garfinkel and Mannheim and enhances analytical possibilities of ethnomethodology because it focuses analysis on “implicit knowledge that underlies everyday practice” and allows to reconstruct social structures and orientation patterns in everyday practice (Bohnsack, Pfaff & Weller, 2010, p.20). Methodological concepts from Documentary Method align with a topical focus on knowledge transformation because they explicitly point to the difference of tacit and explicit knowledge. Documentary Method data analysis reinforces ethnographic analysis methodologically because of its “focus of analysis moves back and forth between the levels of (a) personal sense and (b) principles of fabricating social practices” (Przyborski & Slunecko, 2009, p.143). This dual focus aligns analysis of personal orientations and social structure documented in practical orientations. It also methodologically addresses the criticism that analysis neglects social structure. Social structure as reflected in natural speech and action documents in video and audio data, which is why this data is transcribed for analysis. Analysis of these documents follows Documentary Method strategies for interpretation and focuses on how teachers maintain and transform their orientations.

Documentary Method provides strategies to reconstruct orientation patterns in situated and reflective practice. These strategies reflect in several methodical stages: Formulating interpretation focuses on what is said, the immanent and literal meaning of data, to document issues and topics narrated and described by a participant. Reflective interpretation focuses on how these topics and issues appear in teaching, and respectively how teachers introduce them in narratives, stimulated recalls, and video diaries. Interpretation of orientation patterns takes place through sequential analysis to follow the synchronicity in which teachers introduce their orientations. Sequential interpretation methodically excludes the context of an individual act in a first step and consequently contrasts potential subsequent acts with the actual subsequence realised. Sequential analysis is vital to denote orientation patterns of a teacher within a sequence of classroom interaction. Additionally, narrative interviews, stimulated recalls and video diaries document narratives that embed personal educational knowledge and resulting orientations. This presumption reflects in the narratological axiom that narration and experience are closely connected. Documentary Method analysis was extended to analyse narrative structures and distinguish between different text genres (Nohl, 2010, p.205). Text genres enable analysis to distinguish between (a) descriptive parts of a teacher narration that give account on situated educational knowing and (b) argumentative or evaluative parts that reflect motives behind the action. This distinction segments teacher narrations into parts that address orientation frameworks, orientation schemes, and transformative processes. Transformative processes depend on continual experience of new situations, and perceived discrepancy between planning and practice and consequently provoke changes within these orientation patterns. In reflecting interpretation, the conceptual framework previously outlined acts as a comparative horizon for analysis and draws attention to probable characteristics of transformation of personal educational knowledge, e.g. how teachers experience the classroom as a propositional structure in which they act. Comparative horizons are key elements of comparative analysis and substantiate the validity of empirically reconstructed orientation patterns in a single case, that is, how one teacher performs knowledge transformation. Multiple cases enable comparative analysis across cases, which contrast how teachers maintain and transform their orientation patterns for teaching.

The technological possibilities for fieldwork on transformations of teacher knowledge illustrated here enable us to go beyond retrospections. A multi-sited ethnographic approach combines several fields, and the fields outlined connect retrospective personal narrations teaching practice. This connection establishes in fieldwork, and videography and video diaries are the technological starting points to trace knowledge transformation from ethnographic fieldwork to Documentary Method analysis. This combination enables us to trace how teachers mobilise their personal educational knowledge and transform it for teaching. While classical ethnographic fieldwork relies on participation and the personal fieldnotes created by an ethnographer, new technologies enable us create data that incorporates actions as they took place and verbatim statements of persons in a field. However, such data does not convey the meanings in which a person perceived events. This perception relies on the personal horizon of a teacher. Technology may help us to revisit the reality of an event and invite a teacher to recall how she perceived an event. When talking about an event, this recall becomes part of a narration, and this narration includes associations with previous experience, with memory and professional frames the teacher draws on. Technology as a tool for ethnographic fieldwork may act as a bridge between the objectivity of an event and the subjectivity in which this event was perceived, as both perspectives scaffold the construction of an account on processes of knowledge transformation.

Atkinson, P. (2015). For Ethnography. Los Angeles: Sage.

Bates, J. (2004). Use of narrative interviewing in everyday information behavior research. Library and Information Science Research, 26(1), 15-28.

Bohnsack, R., Pfaff, N., & Weller, W. (2010). Qualitative Analysis and Documentary Method in International Educational Research. Opladen: Budrich.

Borgnakke, K. (2015). Coming back to the basic concepts of the context. Seminar.net – International Journal of media, technology and lifelong learning. http://seminar.net/75-frontpage/current-issue/235-coming-back-to-basic-concepts-of-the-context

Bourdieu, P. (1998). Practical Reason: On the theory of action. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Bruner, J. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Butler, J. (1997). The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection. Stanford: Stanford Univ. Press.

Dempsey, N. (2010). Stimulated Recall Interviews in Ethnography. Qualitative Sociology, 33(3), 349–367.

Dreyfus, H. (2007). Detachment, Involvement, and Rationality: Are we essentially rational animals? Human Affairs, 17(2), 101-109.

Foucault, M. (1986). The Care for the Self (The History of Sexuality, Vol .3). New York: Pantheon.

Foucault, M. (1988). Technologies of the Self. In L.Martin, (Ed.), Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault (p.16-49). London: Tavistock..

Foucault, M. (2005). The hermeneutics of the subject. Lectures at the Collège de France 1981-1982. New York: Picador.

Geerinck, I., Masschelein, J. & Simons, M. (2010). Teaching and Knowledge: a Necessary Combination? An Elaboration of Forms of Teacher’s Reflexivity’. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 29(4), 379-393.

Hammersley, M. & Atkinson, P. (2007). Ethnography: Principles in practice. London: Routledge.

Holliday, R. (2004). Reflecting the Self. In C. Knowles & P. Sweetman (Eds.), Picturing the Social Landscape: Visual Methods and the Sociological Imagination(p.49-64). London: Routledge.

Jovchelovitch, S. & Bauer, M. (2000). Narrative interviewing. In M. Bauer & G. Gaskell (Ed.), Qualitative researching with text, image and sound (p.57–74). London: Sage.

Lyle, J. (2003). Stimulated Recall: A report on its use in naturalistic research. British Educational Research Journal, 29(6), 861-878.

Markham, A. (2013). Fieldwork in Social Media. What would Malinowski do? Qualitative Communication Research, 2(4), 434–446.

Messmer, R. (2015). Stimulated Recall als fokussierter Zugang zu Handlungs- und Denkprozessen von Lehrpersonen. Forum Qualitative Social Research, 16(1), http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs150130

Mohn, E. (2009). Permanent Work on Gazes: Video Ethnography as an Alternative Methodology. In H. Knoblauch, B. Schnettler, J. Raab & H-G.Soeffner (Eds.), Video Analysis: Methodology and Methods. Qualitative Audiovisual Data Analysis in Sociology(p.173-183). Frankfurt am Main: Lang.

Murray, L. (2009). Looking at and looking back: visualization in mobile research. Qualitative Research, 9(4), 469-488.

Noer, V. (2014). Zooming in – zooming out – using iPad video diaries in ethnographic educational research. In P.Landri, A.Maccarini & R. De Rosa (Ed.) Networked together: designing participatory research in online ethnography. Rome: CNR-IRPPS.

Nohl, A.-M. (2010). Narrative Interviews and Documentary Interpretation. Bohnsack, R., Pfaff, N., & Weller, W. (Ed.), Qualitative Analysis and Documentary Method in International Educational Research. Opladen: Budrich.

Polanyi, M. (1998). Personal Knowledge. Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy. Routledge: London.

Przyborski, A. & Slunecko, T. (2009). Against Reification! Praxeological Methodology and its Benefits. In J.Valsiner, P.Molenaar, M.Lyra & N. Chaudhary, N. (Ed.), Dynamic Process Methodology in the Social and Developmental Sciences (p.141-170). Springer: New York.

Putney, L. & Frank, C. (2008). Looking through ethnographic eyes at classrooms acting as cultures. Ethnography and Education, 3(2), 211-228.

Ryle, G. (2009). The Concept of Mind. New York: Routledge.

Saugstad, T. (2005). Aristotle’s Contribution to Scholastic and Non-Scholastic Learning Theories. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 13(3), 347-366.

Schön, D. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York: Basic Books.

Schön, D. (1987). Educating the Reflective Practitioner. Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Walford, G. (2007). Classification and framing of interviews in ethnographic interviewing. Ethnography and Education, 2(2), 145-157.

Walford, G. (2009). The practice of writing ethnographic fieldnotes. Ethnography and Education, 4(2), 117-130.

Watson, C. (2009). ‘Teachers are meant to be orthodox’: narrative and counter narrative in the discursive construction of ‘identity’ in teaching. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 22(4), 469-483.