School of History, Culture and Arts Studies

(Degree Programme of) Cultural Production and Landscape Studies

University of Turku

E-mail: katriina.heljakka@utu.fi

Previous understandings of adult use of toys are connected with ideas of collecting and hobbying, not playing. This study aims to address toys as play objects employed in imaginative scenarios and as learning devices. This article situates toys (particularly, character toys such as Blythe dolls) as socially shared tools for skill-building and learning in adult life. The interviews with Finnish doll players and analyses of examples of their productive, toy-related play patterns showcased in both offline and digital playscapes reveal how toy play leads to skill-building and creativity at a mature age.

The meanings attached to and developed around playthings expand purposely by means of digital and social media. (Audio)visual content-sharing platforms, such as Flickr, Pinterest, Instagram and YouTube, invite mature audiences to join playful dialogues involving mass-produced toys enhanced through do-it-yourself practices. Activities circulated in digital play spaces, such as blogs and photo management applications, demonstrate how adults, as non-professional ‘everyday players’, approach, manipulate and creatively cultivate contemporary playthings. Mature players educate potential players by introducing how to use and develop skills by sharing play patterns associated with their playthings. Producing and broadcasting tutorials on how to play creatively with toys encourage others to build their skills through play.

Keywords: Skill-building, creativity, doll, narratives, photoplay, play, social media, toys

In the Western world of the 21st century, toys are everywhere; playthings of all kinds have expanded from the nursery to sites of serious play, public interiors – offices, studios of artists and designers – not to mention the great variety of products of the entertainment culture, such as television series, films and games. At the same time, player-created content – activities showcased on social media – reveals the ‘real’ toy stories of adults who are coming more actively out of their toy closets. Today, toys and adults go together although a majority of play research is still concerned with the ‘immaterial’ (or ‘free’) play of children.

Over the past years, and probably thanks to the rapidly emerging and expanding academic area of (digital) game studies, play has elevated its status as a topic of research. At the same time, adults are still not addressed as toy players in academic studies related to toys or play patterns associated with them, or rather, their interaction with playthings is discussed in terms of hobbying and collecting, not ‘toying’ with playthings. The research related to object play is still mostly restricted to children’s culture. Interestingly, game playing seems to have overcome this one-sided take on ludic activity some time ago. In fact, the educational and developmental potential related to game playing seems to have gained a steady foothold in Western play discourse. de Jong (2015, p. 17) postulates that the ludification of culture (e.g., Raessens, 2006) has implications for education.

In my view, the practices of ‘toying’ with contemporary dolls contribute to skill-building and learning, even in adulthood. Thus, adult doll play presents a case of possible toyification of learning, that is, toy use aiming at instrumentalised play and the development of different skills, instead of playing only for pleasure. Moreover, I presume that in adult toy play, players are creative, productive and proactive rather than reactive in their actions. At the same time, adults actively use multiple media platforms in both playing and social sharing of their play. In other words, adults are coming out of their toy closets to show their toys and share what they have learned about (and with) them in play.

Reflecting on the current situation, with adults’ growing interest in toys that is made visible through the Internet, adult toy play could be mistakenly considered a recent phenomenon. However, as the (popular) cultural history of toys shows, toys have always appealed to demographic groups other than children. The cultural (as well as industrial and commercial) history of toys shows that they were originally produced as artefacts for adult use (see e.g., Daiken, 1963, p. 102; Hillier, 1965, p. 14; Newson & Newson, 1979, p. 87). From time to time, this interest becomes more distinct and perceivable. As proposed by Sutton-Smith (1997) and Combs (2000), in the ludic age that parallels ideas about the ludification of culture, adult toy play that extends to practices beyond collecting, for example, can be more easily perceived because of the possibilities offered by digital media’s means of communication.

This article aims to identify and analyse creative patterns of playing in relation to adult doll players. The presumption is that these play patterns have become visible through social media applications. By inspecting the play patterns related to the Blythe doll (see Figure 1), specifically, its representations on fan sites, Flickr and the data collected from qualitative interviews and participatory observations conducted at doll meetings with Blythe players in Finland, I demonstrate how toys are used as tools for skill-building and creativity in adult life.

First, the theoretical framework comprises previous theories about ludic activities in relation to manipulation and learning through the use of objects. Second, I discuss the relevance of social media as a ‘toyful’ playground that offers multifaceted possibilities to study adult toy play, particularly with reference to creative object practices with toys, which may lead to skill-building and learning.

Previous theories in relation to ludic activities

Regardless of toy play as a phenomenon that does not restrict itself to children, studies on play have mainly concentrated on the forms of play that are carried out in childhood. As van Leeuwen and Westwood (2008, p. 153) justifiably point out, ludic engagement at an adult age has been almost exclusively studied in a therapeutic context. Adult play may result from factors other than using surplus energy (mainly connected with childhood), specifically, the need for recreation (Groos & Baldwin, 2010, p. 226). Adult play practices related to collecting or other forms of interaction with toys seem to happen most often during leisure time. However, the value and benefits of playthings and interacting with them have also been noted in the areas of design work and management (see e.g., Hunter & Waddell, 2008; Schrage, 2000).

Research on sensory engagement with toys such as dolls (object play) is a rare field of study, even in contemporary toy research. Furthermore, investigations of adult toy play addressing the perspective of skill-building and creativity in relation to these character toys seem non-existent in academic writings. Due to the scarce research literature on adult interaction with contemporary playthings, scholars must try to find theoretical knowledge in other realms of academia. Recent game studies seem to offer an interesting area of research that tackles questions similar to studies on adult toy play. One of these questions concerns the topics of learning and creativity that are accomplished alongside playing due to the intrinsic value of play, in other words, playing ‘just for fun’. According to Sherry Turkle, a psychologist and scholar in digital culture, ‘In video games, you soon realize that to learn to play you have to play to learn’ (1995, p. 70). Learning through play seems to happen without trying, as in the case of many games. Similarly, some toys include a potentiality that intrigues the player to manipulate the plaything in various ways and develop certain skills in the process.

Playing to learn and manipulating to master

While playing, children learn emotionally, physically, socially and cognitively (see e.g., Burghardt, 2005; Izumi-Taylor, Samuelsson, & Rogers, 2010; Piaget, 1962). Both children and adults experience an almost irresistible desire to closely examine any strange object to acquaint themselves with its properties. The cognitive benefits of play are widely recognised. Play begins with exercises focusing on manipulation of material objects. As Sotamaa affirms, with good playthings, a child does not only derive useful experiences from objects but also “learns to learn” (1979, p. 11).

Sensory engagement is a central idea in any material artefact designed for play.

According to Klabbers, “toys involve eye-hand and fine motor coordination, and require planning, imagination, thinking ahead, cooperation, negotiating, sharing, self-control, delay of reward, and last but not least, patience” (2009, p. 5).

What then motivates the player to engage with a toy? A child delights in playing with things that can be put in motion. Some evidence shows that adults enjoy playful artefacts that allow a similar movement of limbs or at least ‘poseability’ (Heljakka, 2013a; Heljakka, 2015). Equally, the possibility to manipulate and thus alter the appearance of an artefact, as is the case with many construction toys, dolls and action figures, is an important feature, such as in the so-called ball-jointed dolls (See Ball-jointed dolls, 2015). For instance, a fashion doll or an action figure that is less articulated and thus affords less poseability also offers less play value than one that provides this kind of manipulation.

Play leads to more challenging tasks, as the feeling of pleasure derived from succeeding constantly develops into a hunger for more demanding challenges (Groos & Baldwin, 2010, p. 5). In toy play, this manifests itself in experimenting with and testing the limits of the toy, both physically and creatively. As media scholar Stephen Kline (2005) argues, different forms of play permit varying degrees of creativity and experimentation.

Doll play seems to offer particularly rich possibilities for this kind of creativity and experimentation, mainly because of the tactile and (in most cases) three-dimensional qualities of dolls. Imagination and creativity play major roles in this interaction with toy objects that are not themselves enhanced with technological features. In other words, being playful in the company of toys seems unregulated, at least to the point that their player is freer to manipulate the toys than a game player would be. How this learning happens in connection with contemporary dolls is explored further by turning to the Blythe doll, its adult fans and the digital playscapes that offer a ‘shop window’ to contemporary cultures of adult toy players.

Social media as ‘toyful’ playground

People play with materials, both individually and with others; Power (2000) differentiates between solitary and social object play. As the material means to toy with things are expanding through an ever-growing universe of playthings, so are the possibilities to connect with likeminded (toy) players in digital media. In this section, I further discuss the playful capacity of contemporary social media platforms.

The Internet is generally viewed as a focal point for groups of people with similar interests, such as fans of various kinds. Fans have always been early adapters of new media technologies, and their fascination with fictional universes often inspires new forms of cultural production (Jenkins, 2006, p. 135). As convergence culture enables new forms of participation and collaboration among fan groups (Jenkins, 2006, p. 256), a playful attitude and engagement towards culture have become even more perceivable.

Brenda Danet (2001, pp. 7—8) regards cyberspace as a site for play because it affords all kinds of activities related to pretending and make-believe, both familiar terms describing different forms of play. Digital media scholars Saarikoski, Suominen, Turtiainen, and Östman support this view by arguing that play, or rather, playfulness, has been one of the most important factors tempting people to engage in online activities (2009, pp. 261–262).

As the Internet has become a ‘social laboratory’ that allows experimentation (Turkle, 1995, p. 180), it has also become possible to perceive toys as material means to practise creativity and to share playful experiences with likeminded people, even in adulthood. These activities are further explored in the context of both analogue and digital aspects of doll play.

Contextualising photoplay on social media

The story of Blythe – the doll type studied here – began in the USA in the early 1970s. The doll was designed in 1972 by Allison Katzman[i] and marketed by the Kenner toy company and later by Hasbro. Today, contemporary versions of Blythe dolls, so-called Neo Blythes, are produced and marketed by the Japanese toy company Tomy Takara under Hasbro’s licence.

The Internet plays an important role in the contemporary phenomenon of Blytheism. Contemporary doll play does not restrict itself to the concrete and manipulable toy object. New media technologies allow players to play with their toys in novel ways, mainly by allowing social sharing of creative digital content. Displaying and sharing digital images have become increasingly popular as the tools have developed online. Besides photo discovery and management services, such as Pinterest and Flickr, YouTube’s role as another type of ‘search engine’ for today’s ‘screenagers’ is undeniable. Aside from televised, animated or music-related content, materials related to toys and play are also sought on YouTube.[ii] In addition to being used as search engines for playthings by transgenerational toy enthusiasts, social media applications also function as catalogues for both contemporary toys and their related play patterns. Photography and video creation have thus gained a significant position among and as part of other pastimes, such as toy play. Alongside photography, social media services may also be considered tools for creative production.

In services such as Flickr, players who photograph their playthings may obtain new audiences and appreciation for their ‘photoplay’ (Heljakka, 2011). In other words, new media offers a perceivable and collective playground for adult players. From the perspective of adult toy play, this development means that people are taking a creative stand towards their playthings by engaging in circulation and re-interpretation of the meanings attached to them. Players are endlessly ‘toying with’, that is, re-appropriating the uses, appearances and narratives of their playthings. These playful interactions are in some cases documented and shared on the Internet through virtual environments that allow networking and social interaction. When examining pictorial representations of toys (toys used as depicted subjects), the questions of play and creativity become significant.

Investigations of adult toy play addressing the perspective of skill-building and creativity seem non-existent in academic writings. This article thus aims to seek answers to the following questions: In which ways does adult toy play extend beyond acquiring and maintaining a toy collection? How can adult toy play contribute to learning and skill-building? Using qualitative interviews conducted in 2014 with Finnish doll players who showcase their play patterns in online spaces such as Flickr, I have aimed to formulate new understandings of adult toy play. In my study, I have elaborated on the creative, productive and digitally shared aspects of toy play with the popular Blythe doll.

To investigate emerging play patterns with reference to contemporary dolls, I have turned to online playscapes employed by fans of Blythe dolls, particularly websites and Flickr pages dedicated to Blythe and the doll players. These players include five Finnish women, aged 30–40+ years,[iii] who have actively engaged with their dolls and other Blythe players, both online and offline at doll meetings, for example. I contacted these interviewees after meeting them in person at doll meetings. Altogether, I invited seven people to participate; five responded and joined the study.

The thematic interviews have been conducted with doll players who are locally and internationally active in their play patterns with physical dolls and on social media. The main theme of the interviews has been to collect data on Blytheism in Finland by finding out about play patterns in relation to this doll type. The interview questions target the phenomenon of adult toy play from many perspectives and aim at a thorough understanding of the motivations leading to and maintaining the play with Blythe dolls. The data collection method has been further enhanced with participatory observations during ‘adult play dates’ organised in Finland and at the international Blythecon event in Amsterdam (2014).[iv]

My goal is to identify and analyse creative patterns of playing, particularly in relation to the Blythe doll. By exploring the adult players’ activities that have become visible through social media applications (e.g., Flickr) and analysing the data collected through qualitative interviews, I have sought answers to how adult toy play emerges. I have further enhanced the data collection by participatory observations conducted at doll meetings and a doll convention.

Using content analysis, I have focused first on mapping the most popular play patterns with reference to Blythe dolls. Second, I have comparatively analysed the discourses on learning and skill-building, as illustrated in the comments by the players in the Finnish interviews and the American Blythe enthusiasts posting on the This is Blythe (TIB) website.[v] This approach brings forward the similarities between Blythe play in Finland and the US, particularly concerning player-generated discourses on skill-building, creativity and learning.

Figure 1. Blythe is a contemporary fashion doll produced by toy company Tomy Takara (Photoplayed by the author, 2015).

This study targets two questions: In which ways does adult toy play with Blythe extend beyond acquiring and maintaining a toy collection? How can adult play with Blythe dolls contribute to learning and skill-building?

Blythe’s story continues today in photographic representations, text-based narratives and audiovisual materials created and shared by different fan communities, especially in the playgrounds of social media. The first encounter with a purchased doll may be documented in an unboxing video. What follows in shared play scenarios is the documenting and sharing of play patterns related to processes of customisation or creating stories, for example, which in some cases lead to ‘tutoring’ on toy play through blogs or tutorials on YouTube. As such, the play patterns in relation to Blythe exemplify a lively dimension of adult interaction with playthings. The activities with Blythe, as in the case of most ‘digital dolldoms’ evolving in fan communities online, involve play practices, such as collecting and creative play. Furthermore, these toys may be appreciated purely for their aesthetic qualities. For some fans, the dolls are family members and thus represent parasocial relationships; for others, the dolls are artefacts that may be used to decorate interior spaces.

Mapping play patterns with Blythe: Discovery, exploration and skill-building

The play patterns that are relevant to the scope of my study are the material, digital and social practices around Blythe dolls. For example, a large fan audience customises and personalises dolls for re-selling purposes; some produce unique dresses and accessories for Blythe and sell them to other doll enthusiasts.[vi] In many Blythe players’ long-term relationships with their toys, the key is to discover the plaything as a potential source of inspiration, as illustrated by an American doll player’s comment on the TIB website:[vii]

She also encourages me to be creative and try new things. She never fails to make me happy!!! Anything that can affect me in a positive way is fantastic!!! I also love blythe because she’s an artistic inspiration that allows me to use my imagination (Jessica, 16, TIB).

Customisation

All play is creative (Kudrowitz & Wallace, 2010). Blythe dolls function as triggers for exploration and creative processes, which unfold in both imaginative reflection and play activities associated with the dolls’ physical features. In this context, creative play refers to the activities inspired by the doll, in addition to traditionally recognised play in which the doll functions as a vehicle for imaginative play.

A trend connecting with the do-it-yourself (DIY) and maker cultures, the personalisation of dolls represents an important direction of creative play practices over the past years. The doll is given a new, individual and customised appearance as a result of the player’s handicraft. As observed, the customisation of Blythe may be linked to its personalisation, all the way from the design and re-creation of its clothes (such as sewing and knitting) to the reinterpretation of its physical features through changing or fine-tuning its eye chips (see Figure 2), face makeup or hair (re-rooting) (How to reroot Blythe doll hair, 2015). In some extreme examples, Blythe fans use their own hair in personalising the doll. Based on my observations during doll meetings or adult play dates, Blythe dolls are sometimes further enhanced with body parts coming from other, more articulated doll types (e.g., Pure Neemo).

The manipulation of Blythe’s hair, facial makeup or skin colour shows that adult play practices in interaction with dolls are not distant from children’s doll play, for example, regarding ‘hair play’ (a play pattern also recognised in industrial toy design). Furthermore, fans advise one another through tutorials, podcasts and blogs. These tutorials may demonstrate different themes, from changing the eye chips of the doll to re-creating its hair, lips and makeup or sewing its clothes. Doll play may also function as an extension of other activities partaken during leisure time. For some fans, the doll offers itself as a tool to extend the play activity to other hobbies, such as handicrafts or photography. Sometimes, playing may lead to skill-building, as in the case of a Blythe player featured in the Fan Spotlight section of the TIB website:

[My favourite thing about Blythe is that] [s]he pushes me to learn new skills. I learned to knit because of Blythe, and my sewing has improved no end. I love to reroot Blythe dolls, a skill I never thought I'd be able to master. She's just a magical doll and the kenner 'pip' in particular is the one thing that can always cheer me up (Jane, 24, TIB).

Creating stories (from display to photoplay)

Displaying toys is an important play pattern in adult toy cultures (Heljakka, 2013a). Toys inhabit bookshelves, cabinets and dioramas built especially for this purpose in the intimacy of players’ living spaces (see Figure 3). As illustrated by the following excerpt from an interview with a Finnish Blythe player, dolls may be given their own ‘houses’ in which different play scenarios are built, sometimes with great care:

The dolls that are less used in play inhabit a “glass palace” [glass cabinet], and the most lucky ones are in my arts and crafts room in a large-scale folder cabinet in which I have made several apartments with kitchens and bathrooms (Pinkkisfun).[viii]

One of the most prominent forms of creative play that follows the display of playthings is photography; many Blythe fans confess taking pictures of their dolls. In adult play activities, the Blythe dolls are styled with personalised looks and photographed in different environments. Singular shots and series of photographs taken in natural or urban environments signify a cross between real and imagined worlds, as the scale of the toy becomes challenging to grasp. In these visual toy stories or photoplay, the player functions as a narrator, and the plaything plays the lead role.

Figure 2. Blythe dolls being customised by changing their eye chips at a doll meeting in Finland, 2014.

Additionally, adult activities with Blythe also include toy tourism and media-related play patterns, which all often tie in with photoplay (Heljakka, 2013a). Photoplaying with the toys outside domestic environments gradually builds the player’s skills in manoeuvring the camera together with toys and the use of tourism sites, urban landscapes and nature. Moreover, players may be inspired to use their acquired camera skills with other types of photography, as stated in this post:

I enjoyed taking photos of Blythe so much that I started taking pictures of other things and now I rarely leave the house without my camera. And through customizing Blythe I've found the perfect hobby, relaxing and rewarding (Sherri, 42, TIB).

The toy photographs are displayed and shared on social media platforms, such as Flickr, and sometimes sold on etsy.com, the ‘online craft fair’ and community launched in 2005. As in other types of toy photography shared in similar environments, Blythe photographs are evaluated and appreciated based on their aesthetic, humorous and inventive qualities. An online search of the available materials in May 2015 generated 1,206,344 hits for the index entry ‘Blythe’ and 1,448 hits for ‘Blythe tutorial’ on Flickr.[ix]

In photoplay, the toy and camera (or another type of mobile device with a camera), together with the chosen environment, challenge a player’s creativity. The Finnish Blythe players ‘Sandy’ and ‘Liiolii’ interviewed for this study also think of displays and play in displays (such as dioramas) as potential settings used in the creative practices of narrativisation and photoplay with Blythe:

[The results of photoplay] are manifestations of creativity [and tell] how one may see possibilities for a picture or a story. Displays used in photographic challenges titillate creativity (Sandy).

Do you see your activities with Blythe as creative? (Author).

Yes. Photographing and play and the telling of stories (both in one’s mind and in pictures) are always creative (Liiolii).

Blythe seems to offer itself particularly well to creative play (as described above) and can thus be regarded as including a creative potential that is partly built in the toy through the aesthetics and mechanics of its design (e.g., through its moving eyes and poseable body), as well as in its possibility to be customised and photoplayed. An additional way to examine creative play with Blythe – customisation and creation of stories through photoplay – is to interpret the re-creations and representations of the doll as a cultivation of what such an industrially designed and mass-produced doll originally offers to its player. Imaginative play patterns, such as naming the doll and creating its personality in one’s mind, are usual practices in the doll play of both children and adults. In an increasingly technologised and socially networked society, the dimensions of storytelling in relation to objects are often taken further, even on the level of the physical artefact – a doll in this case. Many players want to personalise their dolls through physical interventions, for example, changing the look of the dolls through practices related to ‘modding’. However, it is important to note that the cultivation of the dolls does not end here. Instead, playing with contemporary dolls, such as Blythe, continues through the appropriation of camera technologies and social media applications, which results in socially shared play involving skill-building and learning. This is exactly what most of the players are doing with the dolls – manipulating, re-creating and representing Blythe in creative ways – as evident in the research materials collected from interviews and Blythe-related websites.

Figure 3. Creatively customised and displayed Blythe dolls at Blythecon in Amsterdam, 2014.

Learning with Blythe dolls

“In play, and perhaps only in play, a child or an adult has the right to be creative”, says psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott (2005, p. 53). Telling the stories of toy characters makes it possible to explore a person’s creativity in useful ways and for its own sake as well (autotelic) , as explained by an interviewee:

With the dolls, one may find an outlet for creativity in both completely “useless” and useful ways. […] photography, sewing of clothes, making a doll house, problem solving in miniature size – all of these require creativity. But even people who are less creative or whose creativity is in some other area may enjoy dolls with the help of other players’ creativity (Pinkkisfun).

Furthermore, playing with toys entitles people to more than just a way of occupying and entertaining themselves. This study suggests that toy play may also have outcomes that exceed the motivation of ‘playing just for fun’. Besides entertaining themselves, contemporary players are also ‘playing for a purpose’ – to learn and develop skills.

Adult toy play is manifested as a productive type of play, where creativity motivates and drives the play practices. Playing with Blythe as a form of adult toy play reinterprets, remoulds and renews the meanings originally attached to the doll and at the same time, expands these meanings. In play, even adults are allowed to test, be creative and experiment with toys in unforeseeable ways. Creativity employed in toy play becomes perceivable through the concrete outcomes of toy projects, such as play related to Blythe, signifying a joyous activity, not only for the players themselves but also for others. For example, in photoplay, plots involving toys are developed. When presented in a serial mode and posted online on social media, the toy images may attract audiences and followers. Through the photographed toy scenarios, one player’s creativity may thus also influence other players to participate in the ‘game’ of mimetic play.

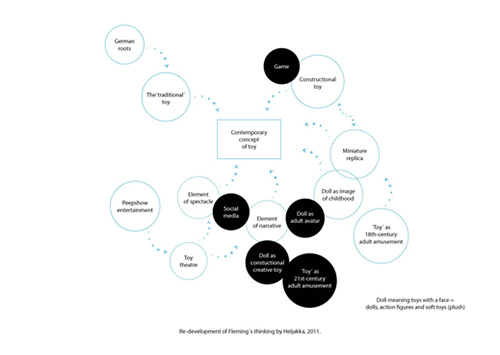

In this light, the contemporary concept of a toy can be perceived as having further developed from Dan Fleming’s suggestion in his book Powerplay. Toys as popular culture (1996). Fleming draws a figure with the historical characteristics converging on the contemporary toy, including phenomena such as the element of spectacle, that of the narrative and the doll as an image of childhood, to name a few. Time has passed since then, and a final suggestion in the framework of this article would be a re-development of Fleming’s thinking, as shown in Figure 4. Based on the ideas proposed in this study, a new version of the graph may include new elements, such as social media, the doll as a constructional toy and furthermore, the toy as a form of 21st-century adult amusement that also caters to the need for goal-oriented, even game-like play patterns related to learning.

Figure 4. Re-development of Dan Fleming’s (1996, p. 92) graph ‘Historical characteristics converging on the contemporary toy’ (Heljakka, 2011, 2013a).

This article concludes with a discussion on how Blythe dolls may be viewed, not only as playthings that exclusively invite individuals to solitary play but also as transformative, social tools that potentially encourage players to develop their skills and creativity and learn further.

This article has explored how to gain new understandings of adult play with contemporary toys such as dolls. Its goal has been to identify and analyse creative play patterns related to adult doll players. It has been presumed that these play patterns have become visible through social media applications. By examining the play patterns related to the Blythe doll (i.e., its representations on fan sites, Flickr and the data collected through qualitative interviews and participatory observations conducted at doll meetings with Blythe players in Finland), I have demonstrated how toys are used as tools for skill-building and creativity in adult life.

Second, I have explored how the dimensions of adult play in digital environments relate to different forms of creativity, self-expression and skill-building that the Blythe doll seems to inspire its fans to do. Through an investigation of visual, material and digital play patterns emerging in social media contexts, I have illustrated how both physical manipulation and the creation and sharing of Blythe dolls’ photographic representations result in skill-building and learning. As Blythe dolls are collected, customised and commercially appropriated through selling of fan art (including imaginative, creative and productive outcomes of photoplay), it becomes possible to observe how visual, digital and shared practices of play significantly shape and enrich adult play cultures with contemporary toys. Without photoplay (filmed or animated toy stories presented on Flickr, Facebook, Instagram or YouTube), it would probably be extremely difficult to capture, analyse and discuss the phenomena related to fashion dolls (such as Blythe) employed in adult toy play or get hold of the players who engage creatively with these playthings.

In the light of the given examples, social media platforms seem to offer themselves as playgrounds full of potential and possibilities – even for adult toy players – where both toys and forms of creative play are cultivated. Blythe seems to inspire its fans to the extent that its individuality can be perceived, not only as a result of the original design work of the toy company but also as something that unfolds through the creative processes and practices learned and taught further by the players.

Psychologists van Leeuwen and Westwood, who have written about the importance of acknowledging the existence of play(ful) behaviour at a mature age, claim that “[…] it is important for psychologists, sociologists, anthropologists and historians to also study adult play conceptually, ‘for its own sake’ as a relevant form of behaviour rather than limited to its role as a means to other ends” (2008, p. 160). Thus, contemporary adult toy play may also manifest itself as a productive activity with creative outcomes although it would have taken place first ‘for its own sake’. Furthermore, once communicated online, various toy projects invite new players to acquire their own toys, get involved in popular play practices and start building their skills around the toys. This means that toys are no longer just recreational objects used for pleasure in unproductive ways by solitary players (for parasocial motivations or as decorations) but also as socially shared and socially played objects. Such objects are potential learning tools that enhance creativity, expanding the toy activity beyond collecting and into various crafts, for example, customising, displaying and photographing the toys.

This study broadens the understandings of toy play in contemporary Western society by pointing out adults (previously thought of as toy collectors or hobbyists) as active, productive and social players. Their play behaviour (as presented on social media as a playful learning environment) results in skill-building, innovative forms of self-expression and tutoring and teaching others to play.

To conclude, it is possible to draw a parallel between the skills developed in toy play and the concept of 21st-century skills, whose list includes “creativity, artistry, curiosity, imagination, innovation and personal expression, among other forms of knowledge, skills, work habits and character traits”.[x] Based on these 21st-century skills, the current generation of students should be taught different skill sets than had been expected of their counterparts in the previous century. In a technology-driven society, it is still possible to recognise the importance of physical objects, especially those that invite learning in playful ways. In this light, it would be appropriate to consider toys, alongside playing with them and with games, as tools for lifelong learning, which could possibly be used in educational contexts as well.

This study has been conducted as part of the Ludification and Emergence of Playful Culture project funded by the Academy of Finland (275421).

Ball-jointed dolls. (2015). Retrieved from http://ball-jointed-dolls.deviantart.com/

Blythe (doll). (2015). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blythe

Blythe fan spotlight. (2010). Retrieved from http:www.thisisblythe.com/fan_spotlight.php?id=23

Burghardt, G. (2005). The genesis of animal play. Testing the limits. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Combs, J. E. (2000). Play world. The emergence of the new ludenic age. Westport: Praeger Publishers.

Daiken, L. (1963). Children’s toys throughout the ages. London: Spring Books.

Danet, B. (2001). Cyberplay. Communicating online. Oxford; New York, NY: Berg.

de Jong, M. M. (2015). The paradox of playfulness: Redefining its ambiguity, S.I.: s.n, Tilburg University. Retrieved from https://pure.uvt.nl/portal/files/5445702/De_jong_Paradox_04_03_2015.pdf

Fleming, D. (1996). Powerplay. Toys as popular culture. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Global world of Pullip (2015). Retrieved from http://www.pullip.net/

Groos, K., & Baldwin, E. (2010). The play of man. Memphis: General Books. (Original work published 1901).

Heljakka, K. (2015). From toys to television and back: My Little Pony appropriated in adult play. Journal of Popular Television, 3(1), 99—109.

Heljakka, K. (2011). Lelukuvasta kuvaleikkiin. Lelukulttuurin kuriositeetti ja kaksoisrepresentaatio valokuvassa. [From toy photography to photoplay. A curiosity in toy culture and double-representation in photography]. Lähikuva, 4, 42–57.

Heljakka, K. (2013b). Lelutarinointia tuubissa: Leikkijä ja liikkuvat uglydoll-kuvat [Toys on the tube: The player and animated Uglydoll images]. In Wider screen, 2–3/2013. Retrieved from http://widerscreen.fi/numerot/2013-2-3/lelutarinointia-tuubissa-leikkija-ja-liikkuvat-uglydoll-kuvat/

Heljakka, K. (2013a). Principles of adult play(fulness) in contemporary play patterns. From wow to flow to glow. (Doctoral dissertation). Aalto University publication series, doctoral dissertations 72/2013: Aalto University.

Hillier, M. (1965). Pageant of toys. London: Elek Books.

How to reroot Blythe doll hair. (2015). Retrieved from http://dolls.wonderhowto.com/how-to/reroot-blythe-doll-hair-271165/

Hunter, Jr. R., & Waddell, M. E. (2008). Toy box leadership. Leadership lessons from the toys you loved as a child. Nashville, Tenn.: Thomas Nelson.

Institute of Museum and Library Services. (2009).Museums, libraries, and 21st century skills(IMLS-2009-NAI-01). Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://www.imls.gov/pdf/21stCenturySkills.pdf

Izumi-Taylor, S., Samuelsson, I. P., & Rogers, C. S. (2010). Perspectives of play in three nations. A comparative study in Japan, the United States and Sweden. Early Childhood Research and Practice, 12(1). Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ889717.pdf

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture. Where old and new media collide. New York: New York University Press.

Klabbers, J. H. G. (2009). The magic circle: Principles of gaming & simulation (3rd ed.). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Kline, S. (2005). Digital play: The interaction of technology, culture and marketing. Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Kudrowitz, B. M., & Wallace, D. R. (2010). The play pyramid: A play classification and ideation tool for toy design. International Journal of Arts and Technology, 3 (1), 36–56. Retrieved from http://www.inderscienceonline.com/doi/abs/10.1504/IJART.2010.030492

Newson, J., & Newson, E. (1979). Toys & playthings. New York: Pantheon Books.

Piaget, J. (1962). Play, dreams and imitation in childhood. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd.

Power, T. G. (2000). Play and exploration in children and animals. Mahwah, N J: Erlbaum.

Raessens, J. (2006). Playful identities, or the ludification of culture. Games and Culture 1(1), 52–57.

Saarikoski, P., Suominen, J., Turtiainen, R., & Östman, S. (2009). Peliä ja leikkiä virtuaalisilla heikkalaatikoilla. [Games and play in virtual playgrounds] In P. Saarikoski, J. Suominen, R. Turtiainen, & S. Östman (Eds.), Funetista Facebookiin – Internetin kulttuurihistoria [From Funet to Facebook – the cultural history of the Internet] (pp. 234–264). Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

Schrage, M. (2000). Serious play. How the world’s best companies simulate to innovate. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Sotamaa, Y. (1979). Introduction. Some general aspects concerning the development of playthings. In K. Otto, K. Schmidt, Y. Sotamaa, & J. Salovaara (Eds.), Playthings for play. Ideas of criteria onchildren’s playthings (pp. 11–13). Berlin: AIF & Ornamo. .

Sutton-Smith, B. (1997). The ambiguity of play. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Turkle, S. (1995). Life on the screen. Identity in the age of the Internet. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks.

van Leeuwen, L., & Westwood, D. (2008). Adult play, psychology and design. Digital Creativity, 19(3), 153–161.

Winnicott, D. (2005). Playing and reality. London: Routledge.

[i] See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blythe (doll) (2015).

[ii] For a study related to character toy play as broadcasted on YouTube, see also Heljakka (2013b).

[iii]This is a typical age range of organised Blythe players in Finland, whereas younger doll players tend to prefer other doll types, such as Pullip dolls (see e.g. Global world of Pullip (2015). When I conducted the study, the five interviewees comprised the highest number of Blythe players willing to join the study that I was able to reach in person.

[iv]The observations were recorded as field notes, with photographs. See Figure 2, for example. Otherwise, no pre-structured format was used.

[v]http:www.thisisblythe.com/fan_spotlight.php?id=23 (This website is no longer available.)

[vi]http:www.thisisblythe.com/fan_spotlight.php?id=23 (This website is no longer available.)

[vii]http:www.thisisblythe.com/fan_spotlight.php?id=23 (This website is no longer available.)

[viii] My interviewees chose the names with which they should be identified. The interviewees’ names (except Sandy) are the pseudonyms they used in their play and shared online activities.

[ix]For Blythe (2015) and Blythe tutorial (2015) on Flickr, see https://www.flickr.com/search/?text=blythehttps://www.flickr.com/search/?text=blythe%20tutorial

[x] For 21st-century skills, see the Institute of Museum and Library Services (2009).