Assistant Professor of Education,

Govt. Degree College 170

J.B Jhang, Higher Education Department (Punjab) Pakistan

Email: mawatto@gmail.com

Literacy is an instrument of stability within and among countries and thus may prove an indispensable means of effective participation in the societies and (the) economies of today’s world. Eradication of illiteracy from the world is an important agenda of UNESCO, and one of the six goals of Dakar Framework of Action on Education for All. Illiteracy is also a major problem in Pakistan. The picture of illiteracy in Pakistan is grim, and although successive governments have announced various programmes to promote literacy the situation is still poor because of various political, social, economic and cultural obstacles. To sum up, it can be said that literacy is a skill necessary to acquire or transmit (information) to others. It is a means not an end in itself. Keeping in view the gravity of the situation of literacy and basic education in the country, Pakistan has completed/implemented a number of actions/activities for broad-based consultations with principal actors of EFA. Furthermore, the Government of Pakistan has accomplished the preparation of provincial and national plans of action and resource mobilization for EFA planning. This paper therefore examines the efforts to decrease illiteracy in Pakistan, a signatory of the worldwide EFA movement.

Keywords: literacy, EFA, development, community, policies, targets.

More than ever before education is seen as a basic need of any social, cultural and economic plan. It is a basic human right and a process through which societies plan their socio-economic development (Mahbub-ul-Haq, 1998). Currently, it is considered "essential for civic order, citizenship, sustained economic growth and the reduction of poverty" (World Bank, 1995, p.4). Without education and literacy it is not possible to realize the goals of balanced and sustainable development. Thus, literacy and basic education are considered a pre-requisite for socio-economic development worldwide. Furthermore, literacy is the pre-requisite for the ability to consult and benefit from major sources of information and knowledge in today’s world (Mark, 1988; UNESCO, 2002). Moreover, knowledge seekers have more facilities today to educate themselves and enlighten their lives (UNESCO, 2004). At the World Conference on Education for All (Jomtien, Thailand 1990) some 1,500 participants, comprising delegates from 155 governments, policy- makers and specialists from around the world, met to discuss major aspects of EFA. In this conference, governments of the world promised to make Education for All a reality by the year 2000. When they met again in 2000 in Dakar, Senegal, it became evident that this objective had not been achieved. Hence, they reaffirmed their commitment to ‘Education for All’ and agreed on a new target year – 2015 (Education International Report, 2003).

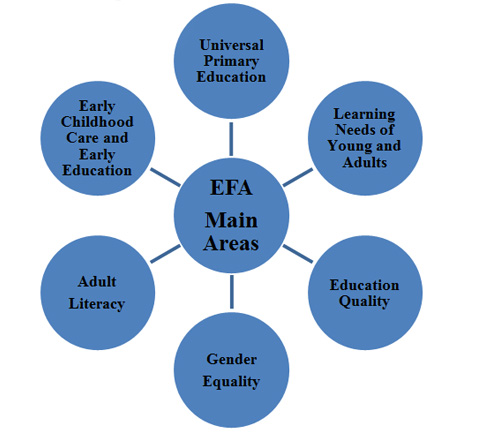

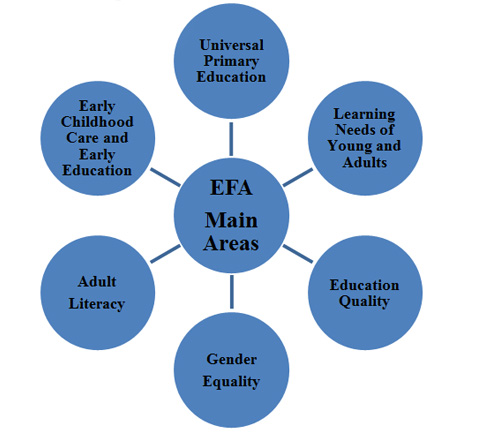

The main areas unanimously approved by the Dakar Forum of Action are shown as below:

Figure:1: EFA Targets

Source: UNESCO, (2006). EFA Monitoring Report, Paris. (p.125)

Since then, governments, non-governmental organizations, civil societies, bilateral and multilateral donor agencies and the media have started literacy work to help children, youth and adults in becoming skilled or literate. However, developing countries are unable to allocate a sufficiently high budget for the implementation of literacy programmes. War, crisis (crises?)and other emergencies are also major hurdles in some countries. Moreover, the traditional educational set up, policies and plans may not be able to cope with the revolutionary pace of the EFA goals of Dakar.

The main purpose of this paper is to present a precise, brief and current/factual picture of the literacy situation in the country and struggle to change the scenario (of literacy) after the launching of EFA in Pakistan.

Education is taken as a basic human right and in the same spirit it was affirmed as a worldwide approach by UNO in 1948 (UNESCO, 2003). To accomplish this right, the concept of Education for All (EFA) was introduced in 1990. EFA simply means basic education for all children (both boys and girls), young and old alike and both male and female as discussed by UNESCO (2005).

Similarly, a global synthesis by UNESCO (2000, p.31) highlights the reality that “Education for all is not only a moral obligation and a right; it is also an investment with very high potential rates of individual and social return.” Therefore, an emerging readiness is desired to incorporate national policies and expenditures with national development plans and development strategies. One key issue within reduction and development is that of literacy; however, due to a number of factors, the goal of 100% literacy has not been met in all countries. In developing countries, the situation is very alarming. About 80% of the world’s illiterates live in 29 developing countries of Asia and Africa (UNESCO, 2006). To cope with the situation the international community began its efforts in 1990 with the holding of the first EFA conference. In short, although EFA is not a new concept, it is an initiative to push for the provision of education for the masses of a society and it also attempts to focus on key issues such as literacy.

The ancient scholar Aristotle was only in favour of elites’ education and discouraged education of the masses. However, with the promotion of Christianity and later on Islam the concept of mass education was emphasized. When Muslims came to the sub-continent of Indo-Pak, there was no idea of mass education. As a result Muslim rulers attempted to introduce education for every person of their kingdom. In the same way, compulsory schooling was gradually introduced in most of the Western European states during the first half of the 20th century (UNESCO, 2005). A parallel improvement could be monitored during the same period in North America and in the countries of Eastern Europe (UNESCO, 2000, p.iii). According to Education International Report (2003, p.15):

When the process of decolonization began after the Second World War, many people expected a similar development in the former colonies. Until the end of the 1970s, such progress could be observed in most of these countries. The number of children and youth enrolled in schools gradually increased as the rate of illiteracy dropped.

In modern times the first voice to support the Education for All was raised by UNO in 1948 (Venkataiah, 1999). To meet the challenge of EFA, the World Conference 1990 established a global programme committed to reducing illiteracy all over the world by the year 2000 (UNESCO, 2004).

From 1990 to 2000, according to Malcolm (2000, p.44), “throughout the decade countries had introduced a wide array of educational reforms either directly within or related to the six target dimensions agreed at Jomtien”. In the World Conference held in Dakar in April 2000 the developments linked to literacy were analysed in a chain of thematic studies, regional synthesis reports, national reports and other documents. It was noted in the Dakar Forum in 2000 that the objectives of the Jomtien conference had not been achieved. Hence, these were reshaped and a new target year was 2015 (UNESCO, 2000a). The other important and prominent steps towards Education for All are known as EFA Flagship Initiatives and EFA Fast Track Initiatives (UNESCO, 20002b).

As far as the role of Education for All movement is concerned, its effectiveness is being recognized all over the world. However, some signs are indicating that the Education for All (EFA) process is not on track. The progress of planning and implementation of EFA in many countries has been slow and facts regarding literacy in Pakistan are no different.

UNESCO is the leading agency in promoting Education for All. The main objective of this organization is:

…to contribute to peace and security in the world by promoting collaboration among nations through education, science, culture and communication in order to foster universal respect for justice, the rule of law, and human rights and fundamental freedoms that are affirmed for the peoples of the world, without distinction of race, sex, language or religion, by the charter of the United Nations (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2005).

To fulfil its mandate, UNESCO performs five principal functions. These principal functions are discussed in NESCO (2005, p.2) as: prospective studies on education and culture; transfer, sharing and advancement of knowledge; standard-setting actions; expertise through technical co-operation to member states; and the exchange of particular information.

UNESCO’s educational programme is traditionally focused on meeting the needs of developing countries. Currently UNESCO and UNICEF are working with some 20 developing countries to design and introduce classroom assessment of learning achievement in Grade 4 of their primary schools. Pakistan is one of them (UNESCO, 2002).

According to Tally, Ba & Tsikalas, (2005, p.41), “UNESCO focuses on support for literacy and non-formal education at the international, regional, national and community levels.”. Its main key task is to facilitate the development of EFA partnerships. Another task is to ensure that the activities of all EFA partners are compatible with one another and consistent with the EFA agenda.

Pakistan is a developing country and also a signatory of the Education for All movement, so the role of UNESCO especially in the field of education is significant. Through UNESCO financial and technical support has been provided to federal and provincial education departments for the formation and commencement of EFA Forums and development of a National EFA Plan of Action. Meetings of Provincial EFA Forums and EFA Technical Groups were held in four provinces, namely Sindh, Baluchistan, Punjab, and NWFP, during March 2001.

Regarding EFA in Pakistan, the first draft of the National Plan of Action for EFA was prepared and presented in the South Asian Ministerial Review Meeting held April 10-12, 2001 at Kathmandu, Nepal (UNESCO, 2001, p.26). UNESCO Islamabad Office extended technical and financial assistance to the Ministry of Education for the preparation of the draft plan and participation of the Pakistan delegation in the Sub-regional meeting. In the same way, UNESCO has supported the Ministry of Education, Government of Pakistan, to undertake an assessment of learning achievement of primary level students during 2001. It also developed a data bank on literacy statistics of Pakistan.

In Pakistan UNESCO’s actions have come under three main headings. The first is providing basic education for all children and the second is fostering literacy and non-formal education among youth and adults. The third main action is known as renewal of education system (UNESCO, 2002). But all these still require UNESCO to do more to enhance the firmness and energy of EFA.

Pakistan is an Islamic Republic with an area of 796 096 square kilometres. It came into existence on August 14, 1947 as an ideological state after the partition of united India into two parts: Pakistan and India. The population of Pakistan in mid 2007 has been estimated at 159.1 million. It is one of the most populous countries in South Asia. Located along the Arabian Sea, it is surrounded by Afghanistan to the west and northwest, Iran to the southwest, India to the east, and China to the northeast.

In Pakistan, the education sector is being adopted as one of the basic tools for poverty reduction and the benefit of the masses. Pakistan started with a very low education profile in 1947, but today the situation is not very poor. The literacy rate reckoned by the number of people who could read only was 16 % in 1951. A short overview of various programmes and practices to tackle illiteracy in Pakistan is given below:

In 2000 the NPA was launched by the Ministry of Education in collaboration with UNESCO to fulfil the requirements of EFA. NPA has focused on elementary education, adult literacy and early childhood education. The estimated targets regarding adult literacy as mentioned in NPA are as under;

1. Phase-I 2001-02 to 2005-06 = 61% (male 71.5%: Female 50.5%)

2. Phase-II 2006-07 to 2010-11 = 68% (male 77%: Female 65%)

3. Phase-III 2010-11 to 2015-16 = 86% (male 86%: Female 86%)

While Pakistan aims at achieving the EFA goals within the context of the Dakar Framework, the reference-definition of literacy is the one as adopted in the 1998 national census. According to this definition, a person of 10 plus age is literate if he/she “can read a newspaper and write a simple letter, in any language.” However, deliberations of different forums on literacy, in the recent past, have also identified the numeracy skills, along with life-skills, as an essential component of literacy. Obviously, the formal adoption of some new definition of literacy is a time-taking process. Now, when Pakistan is striving hard and looking ahead in this direction, the emerging definition of literacy will have to be kept in view while planning for and implementing new interventions for achieving the EFA goals by the year 2015.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights article 26, declared that everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages (Yves and Kishore, 2001). This was also one of the main objectives set at the different international forums (UNESCO, 2002). In this perspective, all the constitutions announced in Pakistan recognized education as one of the fundamental rights of the people (Govt. of Pakistan, 2008). Article 37 (b) of the Constitution of Pakistan (1973) makes it obligatory for the state to eradicate illiteracy and provide compulsory and free education up to secondary level within the minimum feasible period. In line with the above-said constitutional provision, several enactments have been made to provide legal exposure to literacy efforts in the country. They include the following:

The Constitution of Pakistan recognizes that education is a fundamental right of every citizen. It is the responsibility of the Government of Pakistan (GoP) to provide education to its entire populace. In addition to its constitutional responsibilities, GoP has recognized the fact that education is crucial for human as well as economic development.

Being aware of this fact, the Government has put emphasis on increasing access and raising the quality of education in the post Dakar period. To streamline these issues, the MoE developed a ten-year Perspective Plan (2001-11) which provided a broader outline for the development of the education sector in the country. Moreover, a comprehensive Education Sector Reforms Programme (ESR) and National Plan of Action (NPA) for EFA were developed and implemented to realize EFA goals by the year 2015.

Under these initiatives, reform programmes were commenced to provide compulsory and free primary education, provision of free textbooks, overhauling the examination system, revising and updating the curriculum, development of textbooks and learning material policy, enlarging teacher training programmes, capacity building of education managers, streamlining Madrisah education and provision of missing facilities. Technical and vocational education is also getting priority in the reform agenda to cater to the needs of a growing economy and the demands of globalization.

The Government of Pakistan since 1990 has included in all the educational policies the future aspirations and plan for the achievements of the EFA goals. A brief review of these policies is given in the forecoming sections/the sections below.

As a follow-up to the Jomtien Conference a major attempt towards EFA was the formulation of the National Education Policy (1992) in consultation with principal EFA actors both at the national and local levels (Saleem, 2000). The major goals and targets set in this policy towards covering different dimensions of Education for All are summarized below:

a. Compulsory and free Primary Education.

b. Transformation of Primary Education into basic education.

c. Planning for the improvement of literacy rate to 70% by the year 2002.

d. Implementation of literacy programmes through the Provincial Governments, NGOs and local organizations.

e. Utilization of electronic and print media for motivation and to support literacy efforts.

f. Change in curricula, teaching methods and evaluation techniques for quality education.

g. Provision of opportunity for Semi-literate and school drop-outs for upgrading their skills. (Govt. of Pakistan, 1992).

The National Education Policy (1998-2010) was framed in the perspective of historical developments, modern trends in education and emerging requirements of the country. The main policy provisions for EFA are about elementary education, adult literacy and early childhood education. The following targets were fixed in this policy:

a. Access to elementary education through effective utilization of existing facilities.

b. Elimination of gender disparities and diversification of financial resource.

c. Priority to the provision of elementary education to the out-of-school children.

d. Adoption of non-formal system as complementary to formal system.

In the same way, the following measures are proposed to enhance adult literacy:

The latest Educational Policy has determined the following policy actions towards EFA targets:

a. Literacy rate shall be increased up to 86% by 2015 through NFE.

b. Sustainability of adult literacy and NFE programmes shall be ensured.

c. Government shall develop a national literacy curriculum.

d. A system shall be developed to mainstream the students of non-formal programmes into the regular education system

e. Provinces and district governments shall allocate a minimum of 4% of education budget for literacy and non-formal basic education (NFBE).

f. Linkages of non-formal education with industry and internship programmes shall be developed to enhance economic benefits of participation.

g. Special literacy skills programmes shall target older child labourers, boys and girls (aged between 14 and 17 years).

h. Steps shall be taken to ensure that teachers for adult learners and non-formal education are properly trained and have a well-defined career structure allowing them to move into mainstream education.

However, the above-mentioned documents and constitutional steps have remained incomplete mainly due to resource constraints. Pakistan spends 2.1 percent of its GDP on education as compared to India which spends 4.1 percent, Bangladesh 2.4 percent and Nepal spends 3.4 percent. The trend of investment on Education in terms of GDP has been 2.50% and 2.47% in the years 2006-07 and 2007-08 respectively whereas it is estimated to be 2.10% during the 2008-09 which is being decreased; reflecting low political will.

|

Year |

(In Billion Rs.) |

Expenditure on Education |

|||

|

Current |

Development |

Public Sector Expenditure on |

As % of GDP |

% of Total |

|

|

2006-07 |

159.9 |

56.6 |

216.5 |

2.50 |

12.0 |

|

2007-08 |

190.2 |

63.5 |

253.7 |

2.47 |

9.8 |

|

2008-09 |

200.4 |

75.1 |

275.5 |

2.10 |

11.52 |

Table: 1 Expenditure on Education 2006-07 to 2008-09. Source: Economic Survey of Pakistan, 2008-09.

In spite of the said efforts, the situation towards education for all is not very encouraging. Progress in literacy rate no doubt exists but it is very slow. Allocation of budget for the enhancement of education/literacy is still very low as UNESCO suggested minimum 4% of GNP (Govt. of Pakistan, 2004) for developing countries. Theoretically all Pakistani children have a right to education but in practice the majority of school-age children are still out of school and on the other side half of the enrolled children drop out before completing the cycle. In practice, the ‘right to education’ is not attaining its proper status/being fulfilled, sometimes as a result of disability or difference, sometimes through gender, social and economic class, urban or rural situation, regional location, or other factors.

In the same way, efforts have been made through different packages but unfortunately the situation remains unsatisfactory due to non-availability of adequate facilities, lack of political commitment, infrastructure and services for adult literacy especially in remote rural areas. Eshya and Iqbal (2004) described some other factors contributing to the low levels of literacy. These include poverty, lack of educational facilities, especially teaching staff; and parental values which were affected by invisibility of benefits of education.

In the speedily changing era of today’s knowledge, with the progressive use of newer and modern technological means of communication, EFA requirements continue to expand regularly. In order to survive in today’s globalized world, it has become essential for all masses to learn new concepts and expand their ability to locate, evaluate and effectively use information in multiple manners. The targets of EFA will be effectively achieved only when these are planned and implemented in local contexts of language and culture ensuring gender equity and equality, fulfilling learning aspirations of local communities and groups of people. Different programmes launched under EFA must be related to a variety of dimensions of personal and social life, as well as to national development. Therefore programmes of EFA must be related to a comprehensive package of economic social and cultural polices.

In order to achieve EFA targets, the Government must build an active partnership with a variety of stakeholders. It is therefore obligatory to activate the local communities, NGOs, teachers, associations and workers’ unions, universities and research institutions, the private sector and other stakeholders to contribute and participate in all stages of EFA literacy programmes.

The attainment of EFA targets requires adequate funding. The Government of Pakistan needs to mobilize sufficient resources in support of literacy promotion in the country. The following approaches may be adopted at the national level:

i. Incorporate the EFA component across the budget for all levels of education, from basic to higher education;

ii. Attract extra funding through coordination and resources sharing with other ministries and departments where literacy is a component of programmes of advocacy, extension education and poverty reduction;

iii. Mobilize the civil society and private sector to support the Education for All programme.

Similarly, at international level, successful resources mobilization will require:

i. Ongoing consultation among UNO agencies in support on Education for All.

ii. Involvement of bilateral agencies for their financial support and commitment;

iii. Mobilization of international civil society in support of the Education for All programme.

It can be concluded that the EFA programme will have to expand its scope.

Education International Report. (2003). Education for All: Is Commitment Enough? Head Office 5, bd du Roi Albert II B-1210 Brussels Belgium.

Govt. of Pakistan. (1998). National education policy 1998-2010, Islamabad, Ministry of Education.

Govt. of Pakistan. (2004). Education sector reforms: Action plan 2001-2004, Ministry of Education, Islamabad.

Govt. of Pakistan. (2008). Economic Survey of Pakistan (2007-2008). Islamabad: Ministry of Finance.

Govt. of Pakistan. (2008a). Education for all: Mid Decade Assessment Country Report Pakistan; Government of Pakistan Ministry of Education, Islamabad.

Govt. of Pakistan. (2009). National education policy 2009, Islamabad, Ministry of Education.

Mahbub ul Haq & Khadija, H. (1998). Human Development in South Asia, Karachi, Oxford Press.

Malcolm, S. (2000). Global Synthesis Education for All – 2000 Assessment, EFA International Consultative Forum Documents. Paris: UNESCO EFA Forum, 2000.

Mark, B. (1988). Community Financing of Education. National Education Council Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Tally, W., Ba, H., & Tsikalas, K. (2005). Investigating children’s emerging digital literacies. Journal of Technology, Learning, and Assessment, ?(4). Available from http://www.jtla.org.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2002). Primary Teachers Count C.P. 6128, Succursale Centre-Ville Montreal, Canada: Quebec, H3C 3J7

UNESCO. (2000a) Global Synthesis OF UNESCO Education for All assessment 2000. Paris

UNESCO. (2001). Interactive thematic session on education for all; UNESCO (doc. ED-2001/WS/33) UNESCO. 1993a. World Education Report. Paris.

UNESCO. (2002). Literacy Trends and Statistics in Pakistan. Islamabad: UNESCO

UNESCO. (2003). Quality of Primary Education in Pakistan, Ministerial Meeting of South Asia EFA Forum 21-23 May, 2003, Islamabad: UNESCO.

UNESCO. (2004). EFA Flagship Initiatives, Multi-partner collaborative mechanisms in support of EFA goals, 7. France: place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP.

UNESCO. (2005). Education for all global monitoring report 2005: Paris: UNESCO. 7, Place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France.

UNESCO. (2006). Education for all global monitoring report 2006: Paris: UNESCO. 7, Place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France.

UNICEF. (2002b). The State of the World Children, New York: Oxford University Press.

UNICEF. (2005). Progress for Children: A Report Card on Gender Parity and Primary Education. New York: UNICEF.

Venkataiah, S. (1999). Encyclopedia of Contemporary Education Volume 5 Media and Broadcast Education. New Delhi: Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd.

World Bank. (1995). Priorities and Strategies for Education, Washington, D. C.

Yves, D., & Kishore, S.(2001). Education Policies and Strategies2, The Right to Education: An Analysis of UNESCO’s Standard-setting Instruments; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7 place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP.