Universitetspedagogisk sentrum

Stockholm University

Sweden

ulf.olsson@upc.su.se

This study examines the extent to which 387 lecturers at Karlstad University, Mälardalen University and the University of Gävle use certain methods in their blended learning/web-based courses. The teaching methods are compared to the lecturers' conceptions of learning as indicated in the survey. Questionnaires have been used for the survey and responses from lecturers in 10 subjects are compared to each other. The main aims are to compare chosen teaching forms to conceptions of learning, and to compare subject areas with each other according to lecturers' use of methods. In the order of frequency of use, the main stated purposes of using the web tools are: Distribution of materials, communication, administration, evaluation, examination. Three out of four lecturers use a learning management system in their teaching, while only a few use e-meeting tools. The results show similarities at both the department and faculty level, though there are large differences between how lecturers of various subjects report the frequency of use. The relationship between the lecturers' conceptions of learning and the teaching methods used reveal some inconsistencies.

Keywords: teaching methods, e-learning, learning conceptions, higher education

Lecturers in higher education are influenced by both general trends in society and deliberate intervention from outside to utilize information and communication technologies (ICT) to a larger extent. The aims to use ICT in education can be many. ICT can enable increased and widening participation, facilitate handling of course materials, etc. High expectations for ICT in educational settings bitwise were held, both within the university staff and among the students. The expectations and study approaches are influenced and existing quality criteria are affected and have to adapt to the new educational setting. Many studies show, however, that access to ICTs will not be expected to exert any major impact on education unless both technologies and practices for both lecturers and students undergo some changes.Laurillard recalls the roles of the teacher to include not only the subject matter in an educational situation, but also how we learn and how we view the construction of knowledge. “Every teacher plays a part in their nurturing students' epistemological values - their conception of how we come to know - and hence their conception of what learning is, and how it should be done” (Laurillard, 1993, p. 21). This is often not expressed in the curricula, but is found in the discussion of the objectives of a course and forms of implementation and evaluation.

Teaching through seminars, lectures and other classroom-based activities has been and is typical in higher education (Nunes & McPherson, 2003) but it is increasingly common for campus courses to be transformed into blended learning. The use of ICT elements in teaching have often been dependent on individuals (ICT-interested lecturers) or encouraged by the university management to broaden and increase recruitment. Not infrequently, the common teaching methods used in the classroom are transformed into “new” methods in which course materials and lectures shift into digital forms. There is a risk that the participation approach to learning decreases and the transmissions approach to learning increases, though this is not the intent. This can occur when the lectures are recorded and made available through the internet without the opportunity for students to actively discuss or ask questions, or by examinations carried out through automated functions. It can also occur when the time for seminars and group activities is reduced, while the element of one-way activities (from teacher to student) is increasing, often with a more effective outcome in sight.

Ramsden (2003) describes the increased potential of technology to transform education in a way in which the role of technology is to streamline the “delivery” of information to students. Garrison and Anderson (2000), who in their research focus on flexible education expressed concerned that the technology will only enhance the competency to search for information rather than the quality of education. “The question is will technologies be used, in the stronger sense, to create quality learning environments and outcomes, or will they be used simply to enhance presentation quality and access to more fragmented and potentially meaningless information?” (Garrison & Anderson, 2000 p. 33). Siemens wrote in his 2006 review that “Learning management systems have been effective in eliminating the challenges faced by educators in selecting and aligning particular tools with particular tasks” (p. 19). Zemsky and Massy are pointing in the same direction when they argue that the learning management systems make it almost too easy for faculty to transfer their standard teaching materials to the Web (p. 53, 2004).

The relationship between the course design and the students' study approaches are important for achieving a quality education (Prosser & Trigwell, 1997). Thus, the issue of quality in education is also a question of the conception of learning on the part of lecturers. The link is obvious, but the causality unclear. Course design can be related to the lecturers' conceptions of learning and the methods and forms that they choose to use in their teaching with their subjects. The conception of learning is accordingly indicated by the choices that the lecturer makes regarding different methods of teaching and examination, as well as forms of ICT utilized in the course settings. Entwistle and Peterson (2004) refer to the study of Prosser and Trigwell, and consider that:

University teachers using approaches indicating a student-oriented approach to teaching and a focus on student learning (as opposed to a transmission approach) are more likely to have, in their classes, students who describe themselves as adopting a deep approach in their studying. (p. 422)

The introduction of ICT in courses affects teaching practice, but the existing practice also affects the choice and use of technique. The potential to exploit ICT is great even though habits and tradition exert a strong influence. Even when the lecturers are focused on helping students to understand, the actual teaching has tended to focus on knowledge transfer (Kirkwood & Price, 2006). When higher education is expected to encourage a more deeply oriented study approach, this will affect both teaching and examination methods. The relationship between teaching method and study orientation is supported by several studies (Chan & Elliot, 2004; Wierstra et al., 2004; Entwistle & Peterson, 2004; Kember & Kwan, 2000) and often points to the examination forms as being especially influential for the students' study orientation. While other activities in a course are student-centered and can be related to constructivist ideas, the exam form can often be related to learning as reproduction (Bottino, 2004). Students who use a surface orientation tend to appreciate clear factual content, and an exam directly linked to this. Students with deep-oriented study approaches prefer teaching that is relatively more intellectually challenging, as well as examination methods that allow their own ideas to be expressed.

The relationship between good teaching and a deep approach and the (negative) correlation between the appropriate assessment and surface approach are apparent (Ramsden, 2003, p. 104; Kember & Kwan, 2000). With this relationship, the methods used in teaching could be related to the lecturers' conceptions of learning and the conceptions of knowledge that exists in the subject, which is the idea of this paper.

This study[i] examines how lecturers from three Swedish universities consider how often they make use of certain methods and forms of teaching in their blended learning courses. As used in this study, the concept of blended learning is education in which some form of computer use, together with the Internet, takes place. This means that ICT use is limited to the teaching and learning situation, and some form of communication via the Internet occurs. This description excludes the use of ICT in the planning, administration and production phases of a course. The description also excludes the use of computers as stand-alone word processors, etc.

The study is based on material collected from an online questionnaire distributed by e-mail to lecturers at Karlstad University (KaU), Mälardalen University (MdH) and the University of Gävle (HiG). At Karlstad University, the invitation was sent to those who had accounts in at least one of the two learning management systems used at the university. For MdH and HiG, the invitation to respond to the questionnaire, which was addressed to lecturers in blended learning, was sent to all lecturers. The analysis included 387 responses filled in online (159 from KaU, 91 from MdH and 137 from the HiG). The response rate cannot be determined by percentage, as the numbers of lecturers who use ICT in their courses vary with their perception of being included in the definition of blended learning and whether they actively used the web at the time of the survey. We can suppose that the lecturers that responded to the questionnaire were the ones who were the most interested in using ICT in education. The internal loss is zero on the question of which institution and which faculty the lecturers belonged to. Three percent did not specify the subject in such a way that it was possible to classify according to existing topic titles.

The questions posed to the lecturers focused on the use of ICT in their courses, the activities they undertook and how they described learning as a concept. Likert scales with varying degrees of assent (“never”, “seldom”, “sometimes”, “often”, “very often” and “totally disagree”, “agree to some extent”, “agree to a large extent”, “fully agree”) are used.

We shall notice that the analysis is based on lecturers´ statements on the degree to which they use the tools and not on objective tracking or data mining. The assumption that the lecturers interpret the concepts used in the questionnaire differently, both teaching forms and conceptions on learning, should also be taken into account. The conditions of how many students they meet in practice are due to the number of courses the responding lecturers have, how many students participate in the courses and so on. The possibility of making statements about the lecturers´ conceptions of knowledge through the methods used in their courses is limited, whereas the terms and tradition of practice in different subjects are diverse. Some subjects require laboratory work, while other topics may require involvement of the practice fields in order to facilitate understanding of key elements. The consequence is that the subject terms and context strongly affects the possibilities for the design of a course. It is not possible to generalize forms of education outside of its content (Shulman, 1986). Zemsky and Massy stated that “...early adopters need to understand that their success depends as much as the context in which they operate as on the power of the technology they employ” (p. 57, 2004) when they explain the slow adoption of e-learning.

Thus, the degree of “reproduction” and other parameters can only partially be measured by the same scale for different subjects. A course has also to be designed differently depending on the level and type of education that it may encompass. If the course is in a program designed to attract “new” student groups, containing elements such as gatherings at local study centers or distance learning, then controlling the full course designs is beyond the lecturers' reach. To comment on the relationship between the conceptions of learning and the actual methods used is delicate, particularly since a questionnaire simply generates an instant map of answers that should be completed by other methods to achieve higher reliability. All data and results should be interpreted with all these remarks with reliability and validity in mind.

Three out of four lecturers indicated that they either “often used” or “very often used” a learning management system in their courses. Just as many, or rather a slightly larger proportion, stated that they used e-mail in their teaching. HiG had the highest percentage (87%) of universities using the learning management system, which can be explained by the institution's strategy to invest in development, user training and support of the learning management system in use. Mälardalen University does not use videoconferencing at all. Only a small percentage was using web conferences at the three universities. A total of 69% of the respondents had never used web conferencing in their teaching. Some lecturers indicated that they used Skype[ii], but only a few. The results show similarities at the department and faculty levels, although there are big differences between how lecturers of different subjects report their frequency of use.

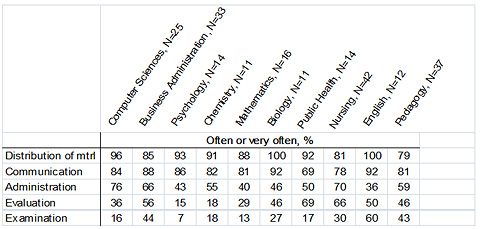

In order of frequency of use, the main uses of ICT are distribution of material, communication, administration, evaluation and examination (see Table 1). Distribution of materials is often the easiest way to use ICT in a course adapted to both the lecturers' and students' expectations and desires. To make use of evaluations and examinations requires the lecturers to be more familiar with the possibilities offered by the ICT tools. Moreover, examination is the final change of the methods in a course when changing from reproductive thinking to more constructivist ideas (Bottino, 2004). In the current study, 14% more lecturers who used ICT for more than four years, compared with those lecturers who used ICT for less than two years, used the examination tools often or very often.

Table 1 - ICT for different purposes in teaching as indicated by lecturers in 10 subjects

The values within each use differ from 21% and 31% for distribution of materials and communication, up to more than 50% for evaluation and examination. The question of whether this difference is due to subject traditions or something else is not unproblematic to comment on. Nevertheless, some indications are given by lecturers' conception of learning.

Table 2 lists the average lecturers’ conception of learning in 10 subjects. In the table, and in the following tables, the highest and lowest values for each conception of learning are highlighted. It is interesting to compare pedagogy lecturers with lecturers of computer science. Furthermore, to agree that “`Learning is a process between people”, lecturers of Pedagogy have indicated to a relatively high degree that “Learning has to do with feelings” and that “Learning is a cultural and historical process”, while lecturers in Computer Sciences have indicated relatively low values for these characterizations of learning. Considering that both these subjects have relatively large amount of respondents, the result is not biased by only a few answers.

|

|

Learning has to do with thinking |

Learning is a process between people |

Learning is an individual process |

Learning has to do with feelings |

Learning is a cultural and historical process |

|

|

Computer Sciences |

Mean |

3.6 |

3.0 |

3.4 |

2,4 |

2.2 |

|

N |

24 |

24 |

24 |

24 |

24 |

|

|

Std.Deviation |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

|

|

Business Administration |

Mean |

3.5 |

3.3 |

3.4 |

2.9 |

2.4 |

|

N |

32 |

32 |

32 |

32 |

31 |

|

|

Std.Deviation |

0.5 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

|

|

Psychology |

Mean |

3.6 |

3.1 |

3.4 |

2.9 |

2.9 |

|

N |

14 |

14 |

14 |

14 |

14 |

|

|

Std.Deviation |

0.5 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

|

|

Chemistry |

Mean |

3.7 |

3.2 |

3.5 |

2.9 |

2.5 |

|

N |

11 |

11 |

11 |

11 |

11 |

|

|

Std.Deviation |

0.5 |

0.9 |

0.5 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

|

|

Mathematics |

Mean |

3.7 |

3.1 |

3.3 |

2.8 |

2.5 |

|

N |

16 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

|

|

Std.Deviation |

0.5 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

|

|

Biology |

Mean |

3.3 |

2.8 |

3.5 |

2.8 |

2.5 |

|

N |

12 |

12 |

12 |

12 |

11 |

|

|

Std.Deviation |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.5 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

|

|

Public Health |

Mean |

3.6 |

3.7 |

3.2 |

2.9 |

3.0 |

|

N |

14 |

14 |

14 |

13 |

13 |

|

|

Std.Deviation |

0.6 |

0.5 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

|

|

Nursing |

Mean |

3.6 |

3.4 |

3.3 |

3.2 |

2.8 |

|

N |

42 |

42 |

42 |

42 |

42 |

|

|

Std.Deviation |

0.7 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

|

|

English |

Mean |

3.7 |

2.9 |

3.2 |

3.2 |

2.6 |

|

N |

12 |

12 |

12 |

12 |

11 |

|

|

Std.Deviation |

0.5 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

|

|

Pedagogy |

Mean |

3.6 |

3.7 |

3.2 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

|

N |

37 |

37 |

35 |

37 |

37 |

|

|

Std.Deviation |

0,6 |

0.5 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

|

|

Total |

Mean |

3.6 |

3.3 |

3.3 |

3.0 |

2.8 |

|

N |

375 |

377 |

373 |

373 |

371 |

|

|

Std.Deviation |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

|

Table 2 - Conceptions of learning indicated by lecturers as derived from Likert scales with varying degrees of assent (“totally disagree”, “agree to some extent”, “agree to a large extent”, “fully agree”). The options have been replaced with the value 1, 2, 3 and 4, which generates the means in the table.

Lecturers in Chemistry have indicated to a relatively high degree that “Learning has to do with thinking” and “Learning is an individual process”. The Biology lecturers indicated to a high degree that “Learning is an individual process” and accordingly to a low degree that “Learning is a process between people”. But at the same time, they indicate to a low degree that “Learning has to do with thinking”. It is noteworthy that the English lecturers' have higher degrees of indicating that “Learning has to do with thinking” and relatively low degrees of indicating that `Learning is a process between people’.

A comparison of the lecturers' use of ICT tools and the lecturers' conceptions of learning cannot be made in a simple way due to the different circumstances linked to the various subject areas. In the various subjects, the lecturers are using different types of methods. Some methods are dependent upon information technology such as databases and students' own discussion forums in the learning management system. Other methods can be used in all courses regardless of whether information technology is available or not.

Some further relations are also noteworthy. Pedagogy lecturers indicate to a high extent that “Learning is a process between people” and are the group of respondents who most frequently use ICT for communication purposes. Lecturers in Biology who use ICT primarily for distributing material have indicated that “Learning is an individual process”, while also indicating that they use ICT for communication to a greater extent than lecturers in other subjects. A lack of correlation has been found among the lecturers in Public Health, who characterize learning as a “process between people” more than other groups, but who use ICT for communication less than other groups.

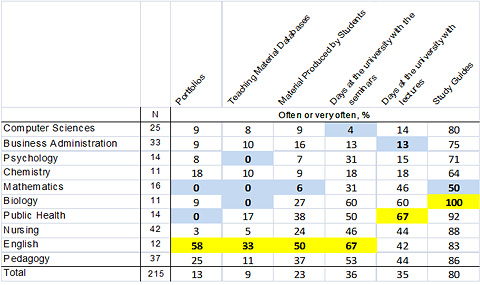

Table 3 - Used methods in teaching as indicated by lecturers in 10 subjects

Table 3 shows how the portfolio methodology, the use of teaching material databases and student-produced materials, including days at the university and study guides, occurs. The data is based on the respondents' statements. Lecturers in English can be said to use the portfolio method to a great extent. More than half the English lecturers use it often or very often. Only one other subject, Pedagogy, will reach as much as 25%. English lecturers also use educational databases to a greater extent than others. “Material produced by students”, as well as the other statements, can be interpreted in various ways, though we can note that the English lecturers are those with the highest percentage (50%), thereby indicating that they use them often or very often.

“Days at the university…” denote that the students travel to the university to participate in activities. These activities are often scheduled at the beginning and completion of the course. They include both days with workshops and days with lectures. One-third of the lecturers organize these activities often or very often. Two out of three English lecturers organize days at the university with seminars often or very often. Two out of three Public Health lecturers of organize days with lectures often or very often. Study Guides are used often or very often by 50% of the Mathematics lecturers and up to all 11 Biology lecturers who answer that they use study guides in their teaching. The Biology lecturers´ use of study guides is not surprising, as they have indicated to a higher degree that “Learning is an individual process”. This can be compared to the Mathematics lecturers who also indicated that “Learning is an individual process” to a higher degree, but who use study guides the least of all.

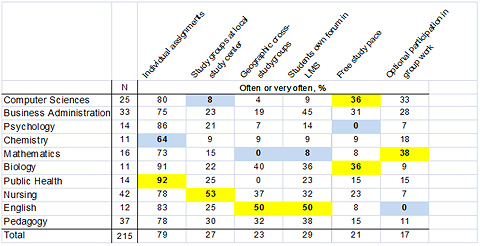

Table 4 includes the types of methods which are relevant to the student's possibility of adapting studies to their preferences and possibilities. The lecturers indicate that they use individual assignments often or very often. More than 90% of Biology lecturers and Public Health lecturers indicate that they often or very often use individual assignments. It is worth noting that only two out of three Chemistry lecturers indicate the same level, despite the fact that these lecturers indicate that learning is an individual process to a large extent.

Table 4 - Use of student study groups in teaching as indicated by lecturers in 10 subjects

The extent of the use of student groups at local study centers largely depends on the type of course. Some courses are advertised so that applicants can find out about a course and apply to their local study centers by using a specific application code. Half the Nursing lecturers indicated that they use this type of student group often or very often. Half the English lecturers are using geographical cross-study groups. This is probably related to the fact that they are the lecturers who use (individual) web conferencing technology to a larger extent than other lecturers. The same proportion of these English lecturers lets the students use their own discussion forums for students groups in the learning management system.

One in three Biology and Computer Sciences lecturers provides the opportunity for students to study at their own pace. The choice of whether to or not work in a group was named to the greatest extent in Mathematics (38%).

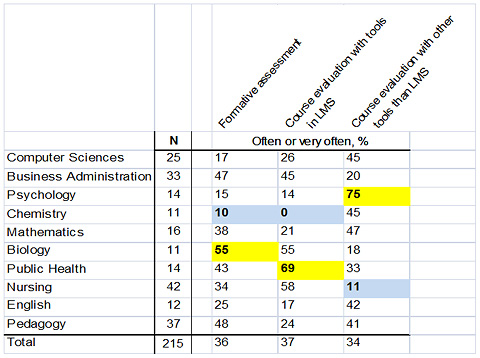

Formative assessment can be understood to represent different things. Although the assessment could be well defined conceptually, both the realization and follow-up can differ greatly. In any case, formative assessments were extensively indicated by the Biology lecturers. Two of three Public Health lecturers of indicate that they use learning management systems (“LMS” in Table 5) to conduct course evaluations. A larger proportion, three of four, Psychology lecturers indicate that they use a course evaluation tool outside the learning management system (see Table 5 below).

Table 5 - Methods of assessments and course evaluations in teaching as indicated by lecturers in 10 subjects

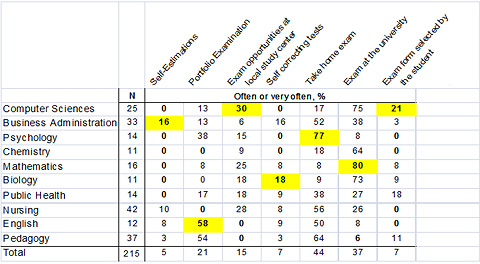

Lecturers were asked to state the extent to which they use tests and examinations, in addition to which forms of these they use (Table 6). From a total of 10 subjects, the most frequent response was take-home exam followed by exam at the university. A total of 77% of Psychology lecturers stated that they used the take-home examination often or very often. Eighty percent of Mathematics lecturers indicated that they used exams at the university often or very often. This can be compared to the result that only a few Pedagogy lecturers indicated that they used exams at the university. A larger proportion of Pedagogy and English lecturers than those of other subjects indicated that they use portfolio examinations instead (54% and 58%).

Table 6 - Examinations in teaching as indicated by lecturers in 10 subjects

Exam opportunities at local study centers exist in most subjects, albeit on a small scale, whereas alternative forms of examinations are little used. Only one in five lecturers in Computer Sciences indicate that they let students choose the examination form often or very often, which was even more unusual in other subjects. Self correcting tests, for example, in the learning management system, as well as self-assessment or diagnostic tests online in the learning management system, were used on a small scale (see Table 6).

In order of frequency of use, the lecturers´ main uses of ICT in this study are distribution of material, communication, administration, evaluation and examination. The results show similarities at the department and faculty levels, but indicate that the lecturers in the 10 subject areas differ considerably according to their use of ICT and their conceptions of learning. We can assume that these differences are the result of many factors, which are specific to individual lecturers, subjects, faculties and other external variables. The possibilities of recruiting new students and well-established cooperation with local study centers could also have shown an influence. We also noticed that the lecturers were asked to state the extent to which they use the tools. This method, and the assumption that the lecturers interpret the concepts used in the questionnaire differently, should be taken into account. The question of whether this difference is due to subject traditions or something else is a delicate one to comment on. Some indications, however, are given by lecturers' conception of learning.

It is interesting to compare Pedagogy lecturers with Computer Science lecturers of. Pedagogy lecturers have indicated to a relatively high degree that “Learning is a process between people”, “Learning has to do with feelings” and that “Learning is a cultural and historical process”, while lecturers in Computer Sciences have indicated relatively low values for these characterizations of learning. The Biologylecturers indicated to a high degree that “Learning is an individual process” and to a low degree that “Learning is a process between people”. But at the same time, they indicate to a low degree that “Learning has to do with thinking”. It is noteworthy that the English lecturers´ indicate to a high degree that “Learning has to do with thinking” and to a relatively low degrees that “Learning is a process between people”.

Besides the difficulties of comparing conceptions of learning to the use of ICT in a valid way, it is interesting to compare the different conceptions themselves and the various uses of ICT. Pedagogy lecturers indicate to a high extent that “Learning is a process between people”, and are the group of respondents who most frequently use ICT for communication purposes. Lecturers in Chemistry have indicated to a relatively high degree that “Learning has to do with thinking” and “Learning is an individual process”, but make use of individual assignments and study guides to a lesser extent. Some further relations are also noteworthy. Lecturers in Biology who use ICT primarily for distributing material have indicated that “Learning is an individual process”, while at the same time indicating that they use ICT for communication to a greater extent than lecturers in other subjects. A lack of correlation has also been found among the lecturers in Public Health who characterize learning as a “process between people” more than other groups, but who indicate the use of ICT for communication less than others.

We can pose the question as to the extent to which threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge in respective subject areas determine the lecturers’ choices in relation to other factors. In the development of pedagogy and teaching methods, we can assume that an exchange of ideas and experience between lecturers from various subject areas and faculties is a learning opportunity for all lecturers.

Bottino, R. M. (2004). The evolution of ICT-based learning environments: Which perspectives for the school of the future? British Journal of Educational Technology, 35(5), 553-567.

Chan, K., & Elliott, R. G. (2004). Relational analysis of personal epistemology and conceptions about teaching and learning. Teaching & Teacher Education, 20(8), 817-831. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2004.09.002

Entwistle, N. J., & Peterson, E. R. (2004). Conceptions of learning and knowledge in higher education: Relationships with study behaviour and influences of learning environments. International Journal of Educational Research, 41(6), 407-428. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2005.08.009

Garrison, R., & Anderson, T. (1999). Transforming and enhancing university teaching: Stronger and weaker technological influences. In Terry Evans and Daryl Nation (Ed.), Changing university teaching: reflections on creating educational technologies,(pp. 24-33). London: Kogan Page.

Gowin, D., & Kember, D. (1993). Conceptions of teaching and their relationship to student learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 63(1), 20-33.

Kember, D., & Kwan, K. (2000). Lecturers' approaches to teaching and their relationship to conceptions of good teaching. Instructional Science, 28(5), 469-490.

Kirkwood, A., & Price, L. (2006). Adaptation for a changing environment: Developing learning and teaching with information and communication technologies. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 7(2), 1-14.

Laurillard, D. (1993). Rethinking university teaching: a framework for the effective use of educational technology. London: Routledge.

Nunes, M. B., & McPherson, M. (2003). Constructivism vs. objectivism Where is difference for designers of e-learning environments? Third IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies, Athens, Greece. 496-500. doi:http://doi.ieeecomputersociety.org/10.1109/ICALT.2003.1215217

Prosser, M., & Trigwell, K. (1997). Relations between perceptions of the teaching environment and approaches to teaching. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 67(1), 25-35.

Ramsden, P. (2003). Learning to teach in higher education. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Siemens, G. (2006). Learning or Management System? A review of Learning Management System Reviews. Learning technology centre, University of Manitoba. Retrieved 17 May 2011 from: http://ltc.umanitoba.ca/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2006/10/learning-or-management-system-with-reference-list.doc

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4-14.

Wierstra, R. F. A., Kanselaar, G., van, d. L., Lodewijks, H. G. L. C., & Vermunt, J. D. (2003). The impact of the university context on European students' learning approaches and learning environment preferences. Higher Education, 45(4), 503.

Zemsky, R. & Massy, W.F. (2004) Thwarted Innovation. What happened to e-learning and Why: A Final Report for The Weatherstation Project of the Learning Alliance. Retrieved 17 May 2011 from: http://helearningalliance.info/WeatherStation.html