Professor

Faculty of Television Production and Film Studies

Lillehammer University College

E-mail: eva.bakoy@hil.no

Assistant Professor

Faculty of Humanities, Sport and Social Sciences

Lillehammer University College

E-mail: oyvind.kalnes@hil.no

Digital storytelling in election campaigns is a relatively recent phenomenon, which needs to be investigated in order to enhance our understanding of changes and developments in modern political communication. This article is an analysis of how the Norwegian-Pakistani Labour politician, Hadia Tajik, has used digital storytelling to construct her political identity, and a discussion of the consequences of her experiments with this genre. The focus is on the five video stories she released during the 2009 parliamentary election campaign and the reactions they evoked on the net and in the traditional media during the same (time) period.

During the 2009 electoral campaign Tajik moved from being a relatively unknown politician to becoming a political household name and the only member of the new Parliament with a migrant background. The digital stories were instrumental in this development for numerous reasons, the most important probably being that they gave her prime time television coverage. Norwegian news media have in general been very concerned with Web 2.0 and Tajik’s videos were regarded as an innovative kind of political communication. The videos also functioned as an effective marketing tool on the net. As an integral part of her extensive viral network, they attracted numerous views and they were with a few exceptions met with positive reactions. This was probably due to their relatively high production values and their catch-all communication strategy that downplayed her ethnic, educational and political background and emphasized her universal human qualities.

Keywords: digital storytelling, net politics, viral networking, multicultural, election campaigns

This article is an analysis of how the Norwegian-Pakistani Labour politician, Hadia Tajik , has used digital storytelling as a political tool. It examines the five video stories she released during the 2009 Parliament election campaign and the response they evoked on the net and in the traditional media during the same year. The 2009 election made her the only Member of Parliament with a migrant background. Using digital storytelling for party political purposes is a relatively recent phenomenon that so far has received little attention from researchers focusing on online election campaigns or digital storytelling in general. A study of Tajik’s digital videos and the considerable attention they received in the Norwegian public sphere may provide important clues to the role digital storytelling will play in the political life of the future.

The term digital storytelling refers to a great variety of emergent digital forms (Lundby, 2008, p. 8). In film studies the term simply means storytelling that explores the options of digital technology. In education digital storytelling is often associated with the Center for Digital Storytelling founded in Berkeley, California in 1998. This center defines digital storytelling as a workshop-based cultural practice “by which ‘ordinary people’ create their own short autobiographical films that can be streamed on the web or broadcast on television” (Burgess, 2007, p. 192). The ideological premise of this concept of digital storytelling is to give people with limited economic means and technical skills a chance to communicate their personal, artistic or political vision to a broader audience. This definition connects digital storytelling to anti-authoritarianism and resistance to social hierarchies and systems of domination and privilege. It also encourages an aesthetic concerned with technical simplicity: still photography rather than live actions embedded in a first person narration. However, today digital storytelling is also part of the establishment. Businesses, politicians, government agencies and other organizations are slowly discovering the power of this mode of communication (Salmon, 2010). In this context, digital storytelling is defined more loosely as a media genre consisting of small-scale web stories with a personal mode of address, which can be used by professional or non-professional media producers alike. This is how Hadia Tajik and this article use the term.

In Norway, where political advertising on television is not allowed, publishing videos on the web provides politicians with an unique opportunity to communicate multimedia messages to potential voters directly without intervention, editorship or control of anyone outside the electoral campaign. Tajik embraced this chance with the support of the Labour Party and the professional multimedia company, CIK Media. This article will argue that Tajik’s digital stories contributed significantly to her present status as a political “celebrity” in Norway with frequent appearances in the media.

Since technological transitions in the mass media always inspire speculations about radical systemic changes in politics, as well as in other areas of social life, Tajik’s videos will also be discussed in terms of how electronic media have changed political communication. Distribution of personal videos on the Internet is part of what has been referred to as Web 2.0 , a new breed of Internet applications that open the Web for active user participation through generating content and engaging in multilateral discussions and networking (O'Reilly, 2007; Pascu, Osimo, Ulbrich, Turlea, & Burgelman, 2007). The scope of the applications varies enormously, including blogging, podcasting, wikis, peer-to-peer technology and social networking sites. The expression “e-ruptions” (Pascu et al. 2007) refers to the “potentially disruptive power” contained in Web 2.0. But an analysis of how political parties have used 2.0 in the UK questions the disruptive scenario, by arguing that established parties and politicians tend to enter Web 2.0 carrying a “mindset” of pre-existing goals and norms” which ensures “politics as usual” (Lilleker & Jackson, 2009). The development of Web 2.0 in Norwegian politics appears close to this last scenario, although currently passing through a steep learning curve of trial and error (Hestvik, 2004; Kalnes, 2009a).

Digital storytelling’s concern with personal stories told in the storytellers’ own words (Lundby, 2008, s. 5) is compatible with the hypothesis that the Internet is going to make politics more candidate and image oriented at the expense of party politics (Røsjø, 2008). The political use of this genre, with the support of a professional production company, can also be interpreted as symptomatic of observations in the party literature that political parties have become increasingly sensitive to the necessity of campaigning and communicating with voters outside the “classé gardé” of the “mass party model” (Duverger, 1967). In the process they have been transformed into “catch all” (Kirchheimer, 1966) or “electoral-professional” parties (Panebianco, 1988) that use experts from outside the traditional party ranks in order to catch as many voters as possible.

The next section presents background information about party politics in Norway, its Web activities and why Hadia Tajik became an important person for the Labour Party’s Web experiments. The rest of the article is divided into three major parts. The first part outlines the analytical approach. The second part discusses the main purpose of Tajik’s digital stories on the basis of a qualitative text analysis, while the third part explores the role of her videos in making her a political household name, by using a number of relevant data published on the Web.

As a consequence of the electoral system and the persistence of a relatively strong centre-periphery cleavage, Norway has a multi-party system, but with the social democratic Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) as its epicenter. Although far from its complete dominance in Norwegian politics in the period 1945-1961, the party still manages to pull around 1/3 of the vote and remains strongly identified with the development of the Norwegian welfare state.

During the last fifteen years Norwegian parties have adapted to the rise of the Internet. By 2005 they had made party Web sites geared towards professional political marketing, conforming to a standard resembling Web 1.0. In the local elections of 2007, Web 2.0 came into play as a campaign tool, and today all Norwegian parliamentary parties have their own YouTube channels as well as being active participants in other Web 2.0 activities. Besides the much smaller Liberal Party, the Labour Party has so far developed the most deliberate Web strategy using Tajik as their online guinea pig (Heftøy, 2009a, 2009b). She quickly established a presence on numerous Web 2.0 sites, and ventured into digital story telling in order to “communicate her views, tell stories about herself and set the agenda” (CIK Media, 2009).

The Labour Party’s choice of Tajik as their online guinea pig can be related to her status as a relatively unknown political figure when her candidacy was proclaimed in October 2008. She then replaced the scandalized Parliament member Saera Kahn - another young, female politician with a multicultural background. Furthermore, occupying the marginal number six position on the Labour Party’s candidate list for the constituency of Oslo made strong promotion of her particular candidacy necessary and beneficial for both Tajik and the party.

To explore the main functions of Tajik’s campaign videos and their relationship to the changes in political communication mentioned above, the analysis has focused on the following questions:

What is the main communicative strategy of the videos?

How does Tajik present herself in the videos?

Who are the implied viewers of the videos and how are they addressed?

The first question will be discussed in terms of three different paths a candidate can follow in pursuing the goal of election: the party oriented path, the issue oriented path or the image oriented path (Bimber & Davis, 2003, p. 44). The party oriented strategy underlines the link between candidate and party. The issue oriented path involves the candidates taking stances in line with various groups of voters, while the image oriented approach makes the personality of the candidates the main selling point. The three paths are usually intertwined to varying degrees in most campaigns. Norwegian politics have traditionally been party oriented, since the electoral system is based on proportional representation and voting for party lists. Consequently, the opportunities of the candidates depend on the success of the party. Individual candidates matter more in the single member constituency systems of for instance the UK and the USA. However, several studies indicate that the effect of television has encouraged a more personalized and candidate-centered politics in Norway too.

The analysis of Tajik’s self-presentation will focus on three dimensions: “…qualification, identification with voters, and empathy” (Bimber & Davis, 2003, p. 74). Qualification refers to the need for the candidates to convince the voters they can fill expectations towards the role of a public official. The second dimension, to communicate identification with the common voters, is about persuading potential voters that the candidate is able to represent their interests. This is typically done by highlighting the fact that the candidate has a background similar to the people in the constituency. The third dimension, empathy, is about showing the voters that the candidates are able to understand their situation, using statements such as “I feel your pain” (Bimber & Davis, 2003, s. 74).

The issue of self-presentation will also be discussed in terms of the degree of formality/intimacy of the candidate’s behavior. On the basis of Erving Goffman’s idea of social life as a multistage drama where human behavior has “onstage” and “offstage” dimensions (Goffman, 1959), Joshua Meyrowitz has argued that the electronic media require a new middle region behavior from politicians. This is a “behavior that lacks the extreme formality of former front region behavior and also lacks the extreme informality of traditional back region behavior” (Meyrowitz, 1986, s. 271). Meyrowitz argues that this is caused by the fact that television stimulates voters to evaluate candidates not just according to their political messages but also in terms of their personal attractiveness, charisma and charm. The camera invades the personal spheres of the candidates and reveals their human shortcomings, making them more like you and me. Politicians try to control the situation by hiring communication experts and personal shoppers and by exposing selected, positive aspects of their back regions in order to please the viewers. But Meyrowitz underlines that: “Yet there is a difference between coping with new situation and truly controlling it “(Meyrowitz, 1986, s. 271).

The term “implied viewers” denotes the hypothetical figures a given text is designed to address. Internet videos are in principle open to all kinds of viewers over a long period and have a potential for gathering a much larger audience than traditional television programs which may be aired only once. But there are numerous difficulties involved in reaching the Internet audience. Unlike radio and television (if they are turned on), the Web cannot interrupt the focus of the citizens and capture their attention. The Web visitor must take several steps in order to view a message, including getting online and actively searching for a particular web site among millions of online choices. The way that people interact with the Web has been described as selective exposure, which means that people tend to seek out information consistent with their ideologies and partisanships. And if they are inadvertently exposed to information that collides with prior beliefs and values, they are likely to reject it as false (Bimber and Davies, 2003, p. 149). The general conclusion among strategists working in the USA has been that traditional party Web sites do not seem to provide a way to convert voters from one candidate or party to another, and because of this political campaigns on the net now address and try to engage three basic audiences: supporters, undecided voters and journalists (Bimber and Davies, 2003, p. 47).

The reactions to Tajik’s videos have been analyzed in terms of attention from net users and traditional media, viewer evaluations and the crucial question of how to attract viewers to the videos in the first place. Counting the number of views compared to the response to videos by other politicians is an obvious first step in measuring the amount of online attention the videos have received. A next step is to look at where these views originated from, in order to find out what may have triggered them. Are they a consequence of the author’s direction, successful networking or attention generated elsewhere? The data used for number of views and their origin were retrieved on December 10th 2009from the YouTube page of each individual video.

The extension of the analysis to other media is necessary, as simply counting views on the Web would lead to an underestimation of the impact of the videos. Digital videos and the Internet are observed by, and referred to, in the traditional mass media, leaving a considerable potential for double spin-off effects. The first spin-off effect is videos leading to exposure in traditional mass media, causing the second, this exposure attracting viewers to the videos. Data on attention in the printed press were gathered through the news service Retriever (Retriever, 2009), while the databases of the two major national TV channels NRK and TV2 were searched for appearances of Tajik in their TV programs during the same period.

The data above say little about individual reactions to Tajik’s videos. The most visible indicators of reactions are of course the elements on the YouTube page that allow the users to interact through comments, discussion, marking as favorite or rating the video. While valuable, these types of visible reactions are limited to only a small portion of the total viewers and should not be taken as representative statements. Viewer reactions also include comments in the press and how guests in the talk show, Grosvold, have evaluated Tajik’s digital stories.

During the campaign in 2009 Tajik published five digital stories on the net. The first two videos, Hadia behind the Scenes (Bakomfilm – Hvem lager hva?) and The Hadia Story (Fortellingen om Hadia), were both released on January 30th . The next video The Women’s Day – Someone is Fighting for Their Lives (Kvinnedagen – Noen sloss for livet) was published on March 2nd, six days before the celebration of the International Women’s Day. The last two videos, The Main Challenges of the School System (Hovedutfordringene i skolen) and Safety in Oslo (Trygghet i Oslo) were available for net users on June 1st and on August 17th. In the following, The Hadia Story will receive most attention since it plays a key role in establishing Tajik’s political persona. The other four videos can be regarded as an elaboration of the character she constructs in this video .

Figure 1: The Hadia Story. Source: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fKo9n7WVkOE, available June 14, 2010

Tajik’s video campaign appears to be based mainly on an image-oriented and issue-oriented strategy. The videos published in late January are heavily image-oriented, while the last three videos present the political issues she is most concerned with: violence against women, teenagers that drop out of school and making Oslo a safer city. However, Tajik’s visual presence and/or voice-over addressing the viewers directly, are the threads that run through and dominate all the videos. Her connection to the Labour party is only briefly mentioned in the backstage video. Studies of online campaigning in the USA indicate that downplaying party affiliation is not unusual. It can partly be explained by the assumption that most of the viewers are supporters who already know what party the candidate belongs to, and partly by worries that too much stress on the party affiliation might scare some of the viewers away (Bimber & Davis, 2003).

Apart from introducing Tajik as a Parliament candidate for the Labour Party in Oslo, the short backstage video (53 seconds) has four major functions. Firstly, by opening the video with an image of a clapperboard familiar from movie making, Tajik is placed in a context associated with a certain glamour. Secondly, it announces her plan to use digital storytelling in order to “tell good stories about important issues”. Thirdly, it communicates that she is responsible for the messages the videos are sending : “I write my own scripts and pick my own topics”. And finally, it gives CIK Media some free advertising: “Without you I would never have managed this. Thank you!” This video constructs Tajik as a grateful and resourceful person who can stand on her own feet and make her own decisions. By underlining that she is in control of the messages, it also identifies her as a dedicated individual rather than a professional party player.

Figure 2: Hadia behind the scenes. Source: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QQiuP0Fl4P0, available June 14, 2010

As already underlined, The Hadia Story is the video most explicitly devoted to constructing Tajik’s image. Dealing primarily with her personal background, it is also the video that corresponds most closely to the conventional concept of digital storytelling. This genre could have inspired Tajik to reveal more of her ‘back region’ behavior than she would have done in a television performance. And The Hadia Story has an intimate dimension that makes it different from how television usually presents politicians. While Tajik is talking about her past, the viewers receive the privilege of watching photographs, apparently from her family album. Looking at someone’s personal album is usually regarded as an act of intimacy. However, the grainy old photos reveal surprisingly little and can best be described with reference to Meyrowitz as ‘middle region’ shots: The pictures of her place of birth, Bjørheimsbygd, are two long shots where it is impossible to see details of the village or the house she and her family live in; the pictures of her parents, siblings and friends are also long shots where facial features are very hard to distinguish.

During the three minutes and thirty-two seconds that The Hadia Story lasts, Tajik tries to convince the viewers that she is a hardworking, goal oriented and experienced person in spite of her young age: she began reading newspapers very early and soon decided to become a journalist. While still in school, she published several articles, and before turning eighteen she landed a summer job as a journalist in Norway’s largest subscription newspaper Aftenposten. The shots where Tajik is telling her story directly into the camera emphasize her seriousness, trustworthiness and eloquence: she is filmed in a medium close up against a black background. The lighting, which makes the right side of her face a little darker than the rest, adds a hint of depth and mystery to the image. Her young face, framed by long wavy dark hair, appears attractive but apart from her hairstyle her femininity is not underlined with visible make up or jewelry. Borrowing an expression from the feminist film scholar, Laura Mulvey (Mulvey, 1975), her image does not connote “to-be-looked-at-ness”. The lack of interesting details in the shot and the fact that Tajik looks directly into the camera with sincere eyes invite the viewer to listen rather than to gaze. Tajik speaks in a rather slow rhythm emphasizing every word, almost preaching to her viewers. Her commentary appears well rehearsed: no stuttering or repetitions. The other four videos support the image of Tajik as a serious, trustworthy and strong person dedicated to creating a better society. Apart from the backstage story, which ends with a seemingly unstaged moment where Tajik says “Cut!” and giggles into the camera, she does not smile much. And the intense, serious voice and the neutral dress and make up are consistent devices in all her digital stories.

As a child of migrant parents and born far from Oslo, Tajik is confronted with a difficult task when trying to communicate identification with the common voters of her constituency. This challenge is addressed by using pictures from Oslo in four of the five videos and by underlining how important Oslo has been in her life. The beginning and the end of a text are conventionally privileged moments. In The Hadia Story the first words Tajik utters is “My first real stay in Oslo changed me”, and the last sentence of her commentary also refers to Oslo (see below). Another strategy is de-emphasizing important features of her background, probably so as not to alienate potential Labour voters. She does not dwell much on the fact that she is the child of immigrant parents. A single photo portrays her in Pakistani clothing, and her commentary refers briefly to her multicultural background as a balancing act between two cultures. Religious beliefs are never mentioned. In terms of social status, she reveals that her mother worked in a grocery, while the career of the father is a blank spot. She also ignores her own university education.

Instead, the video highlights features that Tajik has in common with most Norwegians. It contains several pictures of Tajik as a child skiing and playing in the snow with friends and siblings. And she is concerned with not being regarded as a spokeswoman just for the Norwegian immigrant population. Early in The Hadia Story she tells the viewers that her teacher, Terje, convinced her that in order to have a long life as a journalist she should not limit herself to writing about migrant issues: “…it is better to practice integration that to write about it”. At the very end of the video she finally solves the initial enigma about how Oslo changed her: like her teacher, Oslo made her realize that it is important not to let your ethnic identity and place of birth define who you are. Her last words in the video are:

We often talk about having a home, having roots somewhere. But people do not have roots, we have feet. We can move around freely. Home is something we have in our hearts. And because I have feet and not roots, I am free – and it was mainly Terje and Oslo that made me realize this (Authors’ translation).

Tajik’s issue oriented videos put heavy stress on her empathic abilities. Women’s Day: Some are fighting for their lives emphasizes her empathy with women who are battered by their spouses. Building a bridge to The Hadia Story, this video also begins with a medium close up of Tajik’s face looking seriously into the camera. She is still dressed in neutral black and the background is still dark, but now it consists of dark prison-like bars stressing the tragic dimension of the topic. Tajik says:

There are a lot of things that we do not talk enough about. This is one of them. One of four Norwegian women has been beaten by someone they trust. The offender is a father, brother, boyfriend or husband. Do you know how much it hurts when you love him anyhow? (Authors' translation).

It is especially the use of the personal pronoun “you” in last sentence that emphasizes Tajik’s empathy. The first “you” is an appeal to the social conscience of the viewers. The second “you” refers to those of the viewers who have experienced how it is to be abused by someone they are fond of.

Figure 3: Women’s Day – Some are Fighting for Their Lives. Source: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gjXkXrq9LOA, available June 14, 2010

In The Main Challenges of the School System Tajik’s empathy is put on display by two stories demonstrating her ability to understand individual suffering. One is about Amina who wants to become a doctor like her parents, and loves doing her homework. The second is about Gøran, who like one of five Norwegian pupils does not know how to read and write properly. Both of them end up as” losers” in a school system unable to meet their particular needs. Amina is ignored by the teachers and lacks intellectual challenges, while Gøran is unable to graduate, like every third teenager in the Norwegian high schools.

Figure 4: The Main Challenges of the School System. Source: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lyNTBE9oFQg, available June 14, 2010

In the video Safety in Oslo Tajik’s empathy is directed at several social groups - people who are afraid to walk in the streets of Oslo; criminals with difficult lives, migrants who need help to become a part of Norwegian society and young people who need more leisure activities. The video ends with a statement that underlines Tajik’s empathic understanding of basic human needs: “And most important, everyone needs a job and security in their homes, and help if this is not the case.”

Figure 5: Safety in Oslo. Source: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oJ3f_tx2wio, available June 14, 2010

Tajik’s choice of communicating to potential voters by means of the relatively new genre of digital storytelling can be regarded as a tactic for reaching young voters in particular. They are more active on the net than other age groups and are usually the most undecided voters. But the messages of Tajik’s videos seem to address a much broader range of viewers. Their mode of communication can be described as the previously mentioned “catch all strategy” (Kirchheimer, 1966), which attempts to embrace as many voters as possible by appealing to the lowest common denominator. Tajik presents herself by emphasizing common human values – trustworthiness, dedication, goal orientation. The issues she talks about, helping disadvantaged groups such as battered women, youth or migrants, are not very controversial. And the appeal of her videos relies to a considerable degree on basic entertainment values and eye-catching aesthetic qualities.

In digital storytelling viewer engagement is primarily achieved through narrative means. The Hadia Story isstructured according to basic and popular narrative principles found in fairytales all over the world (Propp, 1968), as well as in mainstream Hollywood moviemaking (Bordwell, 1985). To spur the curiosity of the viewers it opens with an enigma: Why is Oslo so important to Hadia? It continues with a positive presentation of Hadia, designed to make the viewer sympathize with her and her desire to become a journalist. The video typically ends with Hadia reaching her career goal, thereby satisfying the viewers who have identified with her quest. Finally, the video reveals the important life lesson Oslo has taught her: that she is free (see above). This video also attempts to appeal to the poetic sensibilities of the viewers through the rhetorical figure enthymeme: an incomplete or not quite convincing causal connection (Bordwell & Thompson, 1997, p. 140). The enthymeme in The Hadia Story is “…because I have feet and not roots, I am free”. The implied premise – that human being have feet and not roots is obvious – but the conclusion is rather dubious because having feet is usually not sufficient to ensure a person’s freedom.

Narrative principles are as indicated above also the main structuring principle of the issue-oriented video The Main Challenges of the School System. Two characters are introduced: the clever but silent girl and the boy with learning disabilities. The conflict is their meeting with a school system that treats both in the same way in spite of their different needs. This video also catches the attention of the viewer because of its original visual design. The voice-over still belongs to Tajik, but she is absent from the image track. This consists of an animated film with highly stylized, almost abstract images, of the two main characters and their school surroundings: Amina is an all red figure with no facial features, while Gøran is an anonymous figure painted blue. The abstract imagery serves to underline that Amina and Gøran are just two of many teenagers who suffer a hard fate in the Norwegian school system. Their misfortunes are symbolized by a drawing showing a big hole in the floor of the school building. Some of the pupils manage to avoid the hole, but hands stretching out of the gap indicate that not all have been so lucky.

In the videos Women’s Day – Some are Fighting for Their Lives and Safety in Oslo narrative principles typical of digital storytelling are abandoned and replaced by a less entertaining categorical form which focuses on different aspects of the main category which is people living in Oslo city. The aesthetic selling point of the first video is the surprising feature that most of Tajik’s voice-over commentary is found written on objects in the pictures from the city. Her spoken words are for example written on the side of a tram or a taxi, above a shop window or on a traffic sign. Safety in Oslo tries to appeal to the viewers by using images where the talking Tajik is projected onto moving images of Oslo city, sometimes shown in extremely fast motion.

In general the videos have, as already indicated, little to offer audiences interested in political ideologies and how to solve societal problems. Tajik identifies a number of political issues, but she is completely silent about how she is going to reach her political goals. Her position as a Labour Party politician is ambiguous across all the videos, and the basic ideological message of The Hadia Story seems strangely at odds with the social democratic idea of the welfare state as the key to democracy and social justice. In this video, Tajik constructs herself as the incarnation of the self made woman who has achieved her goal to become a journalist in spite of her youth and her immigrant background. Little is said about how the political structure of the Norwegian society has made this possible for her. On the contrary, she stresses her individual freedom and lack of ties to the surroundings, basically sending the viewers a liberalist message about the importance of individual freedom.

The main purpose of Hadia Tajik’s video campaign seems to be convincing potential voters and journalists that she is a serious politician dedicated to creating a better society. She is portrayed as 1) a competent and trustworthy politician experienced beyond her years; 2) like most Norwegians in spite of her migrant background and 3) with a strong ability to understand basic human needs as well as identifying deeply with disadvantaged groups independent of their background. The secondary goal of the videos seems to be a desire to entertain the viewers and appeal to their emotions and aesthetic sensibilities. This is not done by using intimate or sensationalist imagery. Tajik reveals very little of her back region behavior and also moves towards the formal end of middle region behavior. The tools Tajik uses to engage the viewers are primarily narrative enigmas, poetic phrases and fascinating visual effects. Finally, the mode of address of Tajik videos seems designed to include as many viewers as possible. The political issues she talks about tend to be uncontroversial, and her self-presentation appears neutral without any kind of eccentricities, seen from an ethnic Norwegian perspective. The videos are in other words designed to be as non-offensive and inclusive as possible.

In comparison with her political colleagues in Norway, Tajik’s storytelling project has so far been a success in finding an audience on the web. By April 2009 the 420 videos on the official Norwegian party channels on YouTube had accumulated 189,316 views (Kalnes, 2009a, p. 23). By December the same year, Hadia Tajik’s videos had attracted 52,548 views, indicating a 20% market share for her five videos. The first video, The Story of Hadia, aroused the strongest interest with 62.5% of the views. It is quite sensational that a relatively unknown politician can spur such interest within a short span of time.

The relatively high production qualities and entertainment values of the videos were of course important in attracting viewers. But using the internal viral qualities of digital social networking inherent in Web 2.0 was also a vital factor. Most parties or politicians do not yet appear to have cracked the code for taking advantage of these qualities. Tajik’s party, Labour, seems to be closer than the others. By April 2009, it was firmly established as the dominant player on YouTube and other video outlets on the web. Its YouTube videos had captured 93% of all party video views, while having 37% in terms of number of videos (Kalnes, 2009b, p. 27).

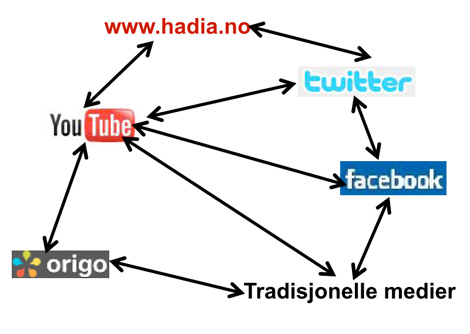

Tajik has been able to utilize the digital networks available on Web 2.0, besides off-line activities, to pull viewers to her videos. In a recent presentation she identified some important pull factors, such as “..bloggers linking to the videos … people twittering about them … coverage in traditional media … ” (Tajik, 2009). All of Tajik’s own on-line and off-line activities were regarded as integral in her promotional strategy, as neatly summarized by herself in Figure 6 below.

Figure 6. Hadia Tajik’s media strategy (Tajik, 2009)

Consequently, Tajik quickly established a diverse web presence extending beyond YouTube. This included a personal home page (http://hadia.no), as well as profiles on social web sites such as Twitter (http://twitter.com/HadiaTajik), Origo (http://www.origo.no/hadia), Facebook (http://www.facebook.com/hadiatajik), and a personal page on the Labour Party's version of mybarackobama.com (http://mittarbeiderparti.no). She was also active in a number of web based social and political networks. According to Tajik, one the functions of these other sites was to continue the debate triggered by her videos (Kirknes, 2009). But they obviously also functioned to promote the videos, though conscious use of referrals and the opportunities offered by embedding of videos.

Tajik was very active on her Facebook page, which reached 1,967 “friends” by January 11th 2010. She had a similarly high activity on Twitter with 752 tweets and 4,274 followers by January 11th 2010. Her profile was one of the most popular in Norway. By May 19th 2009 she ranked as number six on the top list of all politicians and parties with a Twitter profile (http://tvitre.no/norsktoppen). While Twitter in general has a modest reach amongst Norwegian net users in general, it is widely used by journalists.

Data retrieved from YouTube (10.12.2009) i indicate that roughly 80% of the video views were triggered by external links, meaning the viewer saw - or was referred to - the video from other places on the web, through embedsii or links. YouTube's breakdown of the data into sites of origin suggests that up to 60% of the views are generated by networking. But the major part of the networking effect is via users other than herself or the Labour Party.

The views generated by Tajik's own website amounts to 10.37% of all views from external links. YouTube provides no specific data on views from her personal Facebook or Twitter profile. However, YouTube’s data on the views coming from these sites in general indicate marginal effects, as they only reach 0.52%. The share of sites associated with the Labour Party was at 3.15% , and a further 6.51% came from “playlists” and “related videos”. Some of the views in the latter category are probably triggered by watching other videos by Tajik and the Labour Party, or playlists set up by them. Therefore, it may reasonably be estimated that less than 20% of the external views were generated directly by networking from Tajik or her party.

The rather diverse category in YouTube’s data called “other/viral”, accounting for more than 37% of the external views, suggests that the major part of the networking effect is related to the activity of other users. The triggers for these users can be both the on-line and off-line visibility of Tajik, but there is no data on the distribution among them. There is also a significant group of external views (35.04%) coming from search engines. By default, these viewers were not directly guided by the networking of Tajik, the Labour Party or other web users. As Web addresses are rarely provided in the off-line media (i.e. printed press, radio or TV), reports in these media can be expected to trigger use of search engines. Like Tajik herself expressed in the previously cited comment; a successful media strategy does not rely on single sites or media types, but on the conscious use of the interaction between all of them. This is discussed in the next section.

On-line networking, by Tajik herself and others, clearly played a role in directing attention to her videos. But appearances in traditional media are still important in reaching voters, and activity on the web can be an instrument to attract the attention of these media. Of course, this works both ways. Appearances in traditional mass media can direct new audiences to the new Web media, as indicated by the data in the previous section on the significance of search engines.

Off-line, traditional mass media were attributed an important role in Tajik's media strategy and the success of her videos in finding an audience was boosted by journalistic interest. Journalists are in general frequent visitors on the Web and tend to focus on the news value of new technologies. This phenomenon is captured by the “hype-cycle” hypothesis put forward by the American ICT-consultant firm The Gartner Group (Fenn & Linden, 2005; Linden & Fenn, 2003). According to this thesis, the media tend to strongly overestimate the effects of new ICTs while they are still immature. The media attention is therefore disproportional to the actual use and usability of ICTs - hence the “hype”.

The relevance of the hypothesis for ICTs and politics in Norway is shown by the growth in references to popular Web 2.0 sites in the printed press . The media exposure grew from almost nothing in the election year of 2005 to surpassing that of Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg in the next election year of 2009. Consequently, early adapters of new technology, such as Hadia Tajik, may get significant payoffs in terms of coverage in the traditional media. In the next instance, this stimulates public interest in her presence on the Web, and in her political persona in general.

While Tajik got some coverage before the appearance of the videos, these definitely helped her get her some extra attention. Her profile in the printed press was boosted in 2009, compared with the previous year: 393 articles mentioned her name against 167 in 2008. Data for the two major national TV-channels, the public service NRK and the commercial TV2, indicate the same trend. On NRK she got three special TV appearances dedicated to the her videos, once in the Saturday News (July 27th 2009) and twice on talk shows (I Kveld on February 10th 2009 and Grosvold on February 13th 2009). The talk show appearances came just days after the release of her two first videos. Especially Grosvold – a Friday evening talk show with approximately 1 000 000 viewers– must have been invaluable. Excerpts from The Hadia Story were shown in the program, and Tajik herself was given considerable and positive attention for her innovative project (“Grosvold,” 2009; Weiby, 2009).

Hence, there is a double spin-off between new and traditional media. The new media increase “old media” exposure, thereby reaching a wider mass audience and then looping back to get new viewers of the videos. But presence in new media in itself is not a sufficient condition to get attention. It has to be part of a well planned and coherent media strategy. However, the ultimate yardstick for a successful media strategy is not the level of attention but its contribution to a positive image among voters.

For individual candidates and political parties, video-generated attention can be a double-edged sword. Traditional media use their journalistic filters. The characteristic Web 2.0 technologies encourage user feedback, comments, sharing and re-framing, of which YouTube is one of several exponents. As early as in the 2007 campaign, comments in the press from the party leadership and leaders of the information departments of the major and middle-sized parties indicated they all were aware of both benefits and risks of social media (Lundh, 2007; Moe, 2007; Semmingsen, 2007). Interviews of the parties’ professional web managers confirmed this ambivalence, one of them explicitly using the phrase “opportunity AND nightmare” (Kalnes, 2009a, p. 256). While welcoming the new wave of activity from the party members, these professionals obviously regarded “amateurish” videos of politicians as potentially bad publicity. Many of these videos were ridiculed in both the on-line and off-line press (Braaten, 2007; Lüders, 2007; Waagbø, 2007).

However, Tajik's videos turned out to be an exceptional success. They triggered mostly favorable reactions in the traditional media, including the judgments of “expert” commentators. The positive treatment of Tajik in the talk show Grosvold shortly after the premiere of the first videos may have been important in setting the premises (Grosvold, 2009). One of the guests in the program, the Conservative Party’s Per Kristian Foss, characterized the videos as charming, while the Norwegian communication “guru” Kjetil Try found them well made. Try regarded the videos as a smart move in helping an unknown politician establish a public persona in an age where parties matter less and personalities more.

Other commentators viewed the project as innovative, although one expert found the portrayal of Tajik as too polished to reveal the real person (Aftenposten.no, 2009; Helland, 2009). However, the latter critique may be beside the point, as the use of the “middle stage”, rather than “back stage” reflected a conscious choice (Goffman, 1959; Meyrowitz, 1986). On Grosvold both politicians fully agreed that such videos should not be too close or private.

The absence of politics in The Hadia Story was also criticized (Eik, 2009; “Grosvold,” 2009). Tajik defended this by pointing out that this specific video was to be complemented by other videos about political issues (Grosvold, 2009; Heftøy, 2009a). However, as shown in the text analysis, while her later videos discussed political issues there was a striking absence of references to party politics or political ideology.

Regarding ordinary viewers, Tajik’s 5 videos triggered relatively few reactions through the interactive tools available on YouTube during 2009. By December 10th there were 281 registered reactions, in the form of 87 comments, 29 marks as favorite and 165 ratings, in total amounting to 0.5% of registered views. As there is a good chance that a single viewer uses several modes of reaction, far fewer than 1 of 200 viewers actually used the interactive tools. In general, these contained mostly positive feedback.

The average rating of 3.27 on YouTube’s 5-star scale reflects the mainly positive pattern. Many of the comments are also encouraging, saluting Tajik for her storytelling initiative or general qualities as a politician. A user with the nickname The Rat Virgin wrote for instance in a comment to The Hadia Story:

Very nice video. It seems like you have had a very interesting upbringing, providing you with a good basis for political work. Impressive that you were so young when you started writing in the newspapers. I think it is very important to get background information about the politicians we are supposed to vote for, it becomes more personal and one can get a sense about what kind of person you really are, unlike sterile TV-interviews or newspaper articles. Great, looking forward to the next video. (Authors' translation from Norwegian).

However, the risks of exposure and lack of control from the producer side are visible as well. While Tajik herself had played down her immigrant background in the video, many of the comments referred to this, both in a positive and negative way. A substantial share had sexist or anti-immigrant connotations, of a more or less offensive type. Two examples of sexism are the comments from the users amitk19 and torperik to The Hadia Story. The former informs other viewers of “Nice saggy? tits at 30 s(econds)” (original in English). The latter’s comment is less offensive: “She’s pretty, isn’t she” (authors’ translation) . Some viewers used the videos to comment on the Hijab-controversy that Hadia was involved in during the winter 2008/2009. The user kroeg11 wrote in response to The Hadia Story:

What a completely hopeless candidate! – What impertinence, …. My dear girl, learn this: Norway is a non-Muslim country! We have Western culture based on Christian values, and NOT Muslim. Why cannot Muslims live in their own Muslim countries? …. (Authors’ translation)

The videos on Violence against women and Safety in Oslo also triggered reactions from viewers hostile to her background, linking non-Western immigrants and Islam to the issues. It is interesting that the comments indicate an audience beyond the already politically converted. This contradicts the idea that politicians on the Web only reach the already converted voters.

As noted earlier, the personal vote has little significance in Norway, in contrast to the USA, especially in Parliamentary elections. However, the information on the number of changes made by the Labour voters in Oslo tells us that Tajik made a special impression on the voters. Of the 23 candidates on the Labour list only foreign minister Jonas Gahr Støre had more voters changing his position on the list. While this was not sufficient to push her further up on the list, the Labour Party won the marginal seat in Oslo at the sixth position where Tajik was placed. One should be careful to draw any conclusion on the videos' effects on voting, but they undoubtedly contributed to establishing Tajik as a well known Norwegian political personality within a short span of time.

Social media still play a relatively modest role in political campaigns. According to recent surveys from TNS Gallup (TNS Gallup, 2009) and InFact (Andersen, 2009), only 16-17% of Norwegian voters employed such tools to retrieve information or discuss politics during the 2009 campaign. Compared with national TV ratings, the political audiences of the social media are miniscule. By April 2009 all the videos published by the political parties on YouTube had reached less than 200 000 viewers (Kalnes, 2009b). Four daily election specials on NRK TV one week in August 2009, on the other hand, were seen by more than 2.5 million viewers.

This does not necessarily imply that on-line videos are marginal political tools. During the 2009 electoral campaign Tajik moved from being a relatively unknown politician to becoming a political household name. Her digital stories were instrumental in this development, for several reasons. The most important is probably that they gave her prime time television coverage. Norwegian news media have in general been very concerned with Web 2.0. and Tajik’s videos were regarded as an innovative kind of political communication. The videos also functioned as an effective marketing tool on the net. As an integral part of her extensive viral network, as well as the networking of others, the videos received numerous views and were mainly met with positive reactions. This was probably due to their relatively high production values and their catch-all communication strategy that downplayed her ethnic, educational and political background and emphasized her universal human qualities. Tajik’s success in getting exposure on television and the printed press is of course also related to that fact that she is an extraordinary politician in today’s Norway – a young, good-looking woman with migrant background – appealing to the traditional media’s need to include more migrants in their coverage, as well as to their desire to present attractive visual imagery.

Regarding the transformative power of digital storytelling on political communication, Tajik’s experiments with the genre do not indicate substantial changes not already described in the party literature. Web 2.0 tools have the potential to change political communication by creating a non-threatening and inclusive environment for people eager to express their political opinions, but not finding an attractive and available outlet outside the Web 2.0 sphere. Tajik has stated that she uses digital storytelling primarily in order to “engage” potential voters (Tajik, 2009). And apparently her sympathetic presence in the video stories, her catch-all communication tactic and easily digestible political statements may encourage grass root political engagement. But the analysis has revealed that she also uses digital storytelling as a conventional marketing tool, trying to convince as many viewers as possible that she is a serious and goal oriented politician who understands the needs of the voters of her constituency. In this sense, her video can be interpreted as an attempt to steer clear of the widespread opinion among voters of politicians as crude businessmen “trading in votes” (McLean, 1982).

Tajik’s use of digital storytelling, with support from CIK Media and her party organization, can also be regarded as evidence of the increased professionalization of political communication. Her prominent presence in all the videos, combined with mostly uncontroversial political messages, support the thesis that modern politics are adapting to pressures from the electronic media that prefer personal charisma and slogans to serious debates about political ideologies. Tajik’s self-presentation is otherwise consistent with the political middle ground behavior that Meyrowitz has declared as the conventional degree of intimacy in modern political communication. This confirms the point presented in the introduction, that digital storytelling used in a political context is not - for the time being - representing an e-ruption, but rather politics as usual.

Aftenposten.no. (2009, February 10). Ekspertene strides. Aftenposten.no. Retrieved January 7, 2010 from http://www.aftenposten.no/kul_und/article2916662.ece

Andersen, I. (2009, September 10). Velgerne blåser i sosiale medier. VG Nett. Retrieved January 7, 2010 from http://www.vg.no/nyheter/innenriks/valg-2009/artikkel.php?artid=579996

Bimber, B. A., & Davis, R. (2003). Campaigning online: The Internet in US elections. Oxford University Press, USA.

Bordwell, D. (1985). Narration in the fiction film. Routledge. University of Wisconsin Press

Bordwell, D., & Thompson, K. (1997). Film Art. Mac Graw-Hill Companies Inc.

Braaten, K. (2007, August 24). - Noe av det verste jeg har sett. NA24 - Propaganda. Retrieved January 7, 2010 from http://www.na24.no/propaganda/media/article1299646.ece

Burgess, J. (2007). Vernacular creativity and new media. Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane. CIK Media (2009). Retrieved January 5, 2010 from http://www.cikmedia.com/

Duverger, M. (1967). Political parties: Their organization and activity in the modern state. New York: Wiley.

Eik, E. A. (2009, February 10). Personlige politikere. Aftenposten.no. Retrieved January 7, 2010 from http://www.aftenposten.no/meninger/kommentarer/article2916682.ece

Fenn, J., & Linden, A. (2005). Gartner's Hype Cycle Special Report for 2005. Retrieved January 7, 2010 from http://www.gartner.com/DisplayDocument?ref=g_search&id=484424

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday.

Grosvold (2009, February 13). Grosvold. NRK. Retrieved January 7, 2010 from http://www1.nrk.no/nett-tv/indeks/159979

Heftøy, J. E. (2009a, Februar 9). Skal vinne velgere på YouTube. Kampanje.com. Retrieved January 7, 2010 from http://www.kampanje.com/markedsf_ring/article415876.ece

Heftøy, J. E. (2009b, March 9). Arbeiderpartiet kopierer Obama. Kampanje.com. Retrieved December 13, 2010 from http://www.kampanje.com/markedsf_ring/article432248.ece

Helland, J. (2009, June 4). Beste valgkampstunt på nett så langt. Valgpanelet. Retrieved January 13, 2010 from http://valgpanelet.no/forsiden/beste-valgkampstunt-pa-nett-sa-langt/

Hestvik, H. (2004). «valgkamp2001. no» Partier, velgere og nye medier. Ny kommunikasjon? i Bernt Aardal, Anne Krogstad og Hanne Marthe Narud (red.) I valgkampens hete. Strategisk kommunikasjon og politisk usikkerhet. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Kalnes, Ø. (2009a). Norwegian Parties and Web 2.0. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 6(3), 251–266.

Kalnes, Ø. (2009b). Web 2.0 in the Norwegian 2007 and 2009 Campaigns. Paper for IAMCR Conference, July 21-24, 2009 in Mexico City. Retrieved January 7, 2010 from http://intradociep.upmf-grenoble.fr/Spip/IMG/pdf/kalnesIAMCRw2009eb2norwegianparties.pdf

Kirchheimer, O. (1966). The transformation of the Western European party systems. Political parties and political development, 177–200.

Kirknes, L. M. (2009). Velkommen til Valgkamp 2.0. Retrieved December 13, 2009 from http://www.idg.no/computerworld/article139709.ece?mode=print

Lilleker, D., & Jackson, N. (2009). Politicians and Web 2.0: the current bandwagon or changing the mindset. Journal of Information Technology and Politics.

Linden, A., & Fenn, J. (2003). Understanding Gartner's hype cycles. Paper on the Gartner Group’s web site. Retrieved January 7, 2010 from http://www.gartner.com/pages/story.php.id.8795.s.8.jsp

Lundby, K. (2008). Editorial: mediatized stories: mediation perspectives on digital storytelling. New Media and Society, 10(3), 363.

Lundh, F. (2007, April 21). Jens åpnet Ap-kanal på YouTube. VG Nett. Retrieved December 30, 2009 from http://www.vg.no/nyheter/innenriks/norsk-politikk/artikkel.php?artid=172252

Lüders, M. (2007, August 25). Nettvalgkamp til stryk. Dagens Næringsliv.

McLean, I. (1982). Dealing in votes. New York: St. Martin's Press.

Meyrowitz, J. (1986). No sense of place. Oxford University Press US.

Moe, I. (2007, February 19). Få toppolitikere bruker blogger— . . . men alle er enige om at Internett blir viktigere. Oslo: Aftenposten.

Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual pleasure and narrative cinema. Screen, 16(3), 6.

O'Reilly, T. (2007). What Is Web 2.0: Design Patterns and Business Models for the Next Generation of Software. Communications & Strategies, (65). Retrieved December 13, 2009 from http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/4578/

Panebianco, A. (1988). Political parties: organization and power. Cambridge, [England] ; New York : Cambridge University Press.

Pascu, C., Osimo, D., Ulbrich, M., Turlea, G., & Burgelman, J. C. (2007). The potential disruptive impact of Internet2 based technologies. First Monday, 12(3-5).

Propp, V. I. (1968). Morphology of the folktale. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Retriever. (2009). Database. Retrieved May 6, 2010 from http://retriever.no/

Røsjø, B. (2008, February 19). Internett gir meir personfokus i politikken. forskning.no. Retrieved May 6, 2010 from http://www.forskning.no/artikler/2008/februar/1203005085.14

Salmon, C. (2010). Storytelling: Bewitching the Modern Mind. London, New York: Verso.

Semmingsen, I. (2007, June 21). Uten nettsatsing mister du velgere. VG Nett. Retrieved January 7, 2010 from http://www.vg.no/nyheter/innenriks/norsk-politikk/artikkel.php?artid=144597

Tajik, H. (2009, April 17). Valgkampen 2009 foregår på nett. Slideshare. Retrieved January 11, 2010 from http://www.slideshare.net/Friprog/hadia-tajik-valgkampen-2009-foregar-pa-nett

TNS Gallup. (2009). Sosiale medier påvirket få personer i valgkampen. Retrieved January 5, 2010 from http://www.tns-gallup.no/print.aspx?did=9088157

Weiby, H. E. (2009, February 13). Generasjonskløft i valgkampen. NRK Nyheter. Retrieved January 6, 2010 from http://fil.nrk.no/nyheter/1.6480891

Waagbø, A. J. (2007, August 9). Se valgvideoene ekspertene slakter. Nettavisen. Retrieved January 7, 2010 from http://pub.tv2.no/nettavisen/innenriks/valg07/article1266375.ece

Tajik was born in Norway in 1983, by Pakistani immigrant parents. Unlike most immigrants, who live in the Norwegian capital, Oslo, she grew up in a small village in the south-western part of the country. At the age of sixteen she became leader of the local branch of the Labour Party's youth organisation (Arbeidernes Ungdomsfylking). While taking university education and practicing as a journalist, her political career took off. From 2006 she served as political advisor in different government departments, including the Prime Minister's office.

Hompepage Center for Digital Storytelling: http://www.storycenter.org/history.html, retrived April 28, 2010.

A recent judgement in the European Court of Human rights challenged this prohibition, but the Government has so far been able to avoid the dissolution of the law.

”Classé garde” refers to that the ”masses” mobilized – or sought mobilized – by particular parties belonged to specific social classes or –groups.

The term is taken from Wolfgang Iser (1972), a literary theorist belonging to reader-response criticism.

As the videos are in Norwegian, those not familiar with the language are advised to take advantage of the caption service on YouTube to get English subtitles. This is available through the small arrowhead in the lower right corner of the video.

It is not known to what degree the Labour Party was involved in the

script-writing process.

Active searchesfrom users represent views triggered byreferrals from the three search engines mentioned in the data;YouTube's internal search engine, Google and the Norwegian ABC-søk(http://verden.abcsok.no).

Personal direction fromTajik represents views triggered bylinking to or embedding the videos on Tajik's website(http://hadia.no). Direction via partynetwork represents views triggered bylinks or video embedding on sites or pages belonging the LabourParty, as well one important party members blog named by YouTube(http://sosialdemokrat.blogspot.com)

Other specifiedis other sites specified, but not directly related to the partynetwork. Facebook and Twitter may of course contain views triggeredby Tajik's or Labour Party presence on these sites. Other / viral generalare what YouTube has classified as other / viral.

"Embeds" are referring to instances wherethe videos uploaded to a site (in this instance YouTube) can beviewed directly on other web sites/pages. This is possible through aparticular code, often easily available beside the original page,which can be copied and pasted into any other page.

The printed press werechecked by number of mentions of Twitter, MySpace Nettby, Flickr,Facebook, YouTube and blog* against "jens stoltenberg" inRetriever(https://Web.retriever-info.com/services/achive.html),which is the main national database of media contents.

Source: Retriever https://web.retriever-info.com/services/archive.htm. Articles in major newspapers in Retriever database containing phrase "Hadia Tajik" 01.01.2008 - 29.12.2009.

Sources: Search on NRK and TV 2 January 11.01.2010, http://www.tv2.no/TV2/do/fsearch?stolpe=all&querystring=hadia+tajik

http://www1.nrk.no/nett-tv/sok/hadia+tajik. Only results referring TV-appearances included.

This is an estimate from the 970 000 viewers reported watching the previous show (Wekre, 2009).

Representing a method of self-selection, the recorded user reactions cannot qualify as a representative sample of all viewer reactions.

At the time Tajik was political advisor to the absent Minister of Justice and had apparently sanctioned the Ministry’s accept of female police officers using Hijab.

To have any effect more than 50% of the votes cast for the same party list must contain exactly the same change in the individual candidate’s position (Oslo kommune, Bystyrets sekretariat, 2009).