Graduate student in anthropology

PhD Candidate

Anthropology Department

University of California, Los Angeles

Email: amber.reed@ucla.edu

MA, Gender studies

Founder and director of the Center for Digital Storytelling’s

Silence Speaks digital storytelling initiative

Email: amylenita@storycenter.org

As resources become available, the tools of digital storytelling are being introduced into a wide variety of contexts, with new projects involving youth emerging in increasingly remote areas throughout the developing world. In 2008, the Sonke Gender Justice Network teamed up with the Center for Digital Storytelling’s Silence Speaks initiative to work with a group of rural youth in Eastern Cape, South Africa. The results of this project are eight digital stories by young Xhosa people that capture the challenges they face and the futures they yearn for in post-apartheid South Africa. By exploring the success and challenges of the project, we show the potential that thoughtfully designed digital storytelling efforts offer as both a psychological outlet and a tool for community education and social activism with marginalized youth.

Keywords: Youth, Digital Storytelling, South Africa, HIV/AIDS, participatory video, gender-based violence.

“I liked what Sonke did, so I told my friends. So now we do something like that. If someone has a problem we say, ‘Don’t keep it to yourself! No – you can tell us.’ ” (Tokozile, June 8, 2009)

What happens when youth are asked to share personal stories and take photographs in the service of producing short-form videos that capture the challenges and opportunities facing their community? This article explores the possibilities and pitfalls of digital storytelling with marginalized young people by presenting a case study of a project conducted in Eastern Cape, South Africa in 2008.

Over the past 15 years, the emerging participatory media production method known as digital storytelling has been taken up in numerous community, health, educational, and academic settings. Drawing from well-established traditions in popular education, participatory communications, oral history, and, most recently, what has been called “citizen journalism,” practitioners of digital storytelling in localized contexts around the world are working with small groups of people to facilitate the production of short, first-person digital videos that document a wide range of culturally and historically embedded lived experiences (Lambert, 2002; Burgess, 2006).

Anthropological writings on youth resistance have pointed to the importance of personal narratives in creating engaged citizens of a democratic state. As theorist and practitioner Karen Brodkin explains, the ability to narrate one’s own life story is an essential part of becoming what she calls a “political actor” (2007:14). Brodkin continues: “To create a narrative is to exercise personal agency, to act upon society…Being the interpreter of events makes the narrator an active agent in constructing the world” (50). Lastly, she sees the telling of stories as often leading to exponential results, in which others are encouraged to speak out when they would have otherwise remained silent (53).

At the level of community-based health practice, narrative is increasingly viewed as an effective tool for motivating and supporting health-behavior change. In their overview of this growing field, Hinyard and Kreuter write, “When audience members become immersed in a narrative, they are less likely to counter-argue against its key messages, and when they connect to characters in the narrative, these characters may have greater influence on the audience members’ attitudes and beliefs” (2007: 785).

The Center for Digital Storytelling’s Silence Speaks initiative builds on these perspectives in its work to support the telling and witnessing of stories that all too often remain unspoken. The initiative is grounded in the notion that personal stories can inspire, educate, and move people deeply, and that when it comes to confronting complex social issues, the connections forged through storytelling can help people bridge the vast differences that often divide them and instead act with wisdom, compassion, and conscience. Silence Speaks stories are shared locally and globally, as tools for training, community mobilization, and policy advocacy to promote health, gender equality, and human rights both locally and globally.

Established in 2006, Sonke Gender Justice works in Southern Africa to create the change necessary for men, women, youth, and children to enjoy equitable, healthy, and happy relationships that contribute to the development of just and democratic societies. Sonke uses a human rights framework to build the capacity of government, civil society organisations, and citizens to achieve gender equality, prevent gender based violence, and reduce the spread and impact of HIV and AIDS.

Crucial to the success of Sonke's work is ensuring a central role for those most directly affected by violence and HIV. Since 2007, Sonke and Silence Speaks have been working together to enable young people and adults affected by violence and HIV and AIDS to share their stories. From cities to rural villages, the project offers participants a rare opportunity to talk about their own experiences and bear witness to the lives of others, in a supportive setting. Through intensive, participatory video production workshops, rarely heard voices and images are brought into the civic arena. The hope is to deepen existing conversations about gender norms and the spread of these twin epidemics, by highlighting everyday stories.

To date, eight workshops have been held, and four story collections with accompanying discussion guides have been developed. Stories have been integrated into Sonke training manuals on men’s role in supporting survivors of sexual assault and on gender and health issues within migrant communities. Collections of the Sonke digital stories will soon be aired on health and educational television channels and via community radio.

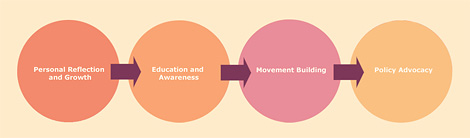

The Sonke – Silence Speaks collaboration has led to the creation of an important model of the multiple impacts of digital storytelling, which rests in a continuum of strategies for developing and sharing stories – from stories that are created as part of the individual healing and growth of workshop participants, to stories that are utilized to educate, mobilize communities, and help change policy. Below is a graphic representation of the continuum that describes the ways in which the digital storytelling process and the videos produced through this process can elicit and document change at a number of levels:

Figure 1. Continuum of Digital Storytelling Impacts

The following two-part case study shows a particular instance of this model being put into practice. Part I describes how South African youth were brought together by Sonke and Silence Speaks to create digital stories about their lives, in a workshop that evaluation research shows nurtured their reflective capacities and supported them in growing as young leaders. The stories these youth produced are being shared as prompts for community dialogue and action and as evidence for the need to address pressing health issues in Eastern Cape Province, although these activities were beyond the scope of the evaluation described. Part II describes a small-scale exploratory research project that explores the feasibility of using the stories as teaching tools in classroom settings.

Mhlontlo Municipality, located in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa, is characterized by high rates of HIV/AIDS, poverty, and violence. Children and youth in this region deal with a host of challenges: losing family members to AIDS, witnessing domestic violence in their homes, enduring regular shortages of nutritious food and clean water, and experiencing sexual abuse and exploitation. They are growing up in the shadow of what many theorists have branded the “lost generation” that came of age in the years immediately following the demise of the apartheid regime, and, like this generation, have had little support for learning to oppose dominant power structures (O’Brien, 1996, p. 55). To compound these problems, Sonke’s experience in the field has shown that young people in Mhlontlo have little access to formal counseling and supportive services that might help them cope with such stressors.

Sonke has pioneered several initiatives in Eastern Cape, including gender equality training, responsible fatherhood projects, and individual skill building for HIV and violence prevention. Through its ongoing partnership with Silence Speaks, and in collaboration with schools and NGOs in Mhlontlo, Sonke has begun bringing young people’s voices to the forefront of these efforts. The rationale behind this approach is that encouraging the telling of otherwise silenced stories will help workshop participants and other youth who view the stories learn to manage difficult experiences in their lives and serve as a springboard for enhancing their capacities for leadership and involvement in community transformation for justice.

In September 2008, Sonke coordinators in the municipality began doing outreach to young people, to assemble a group interested in creating digital stories. Potential participants were briefed in advance on the production methods to be used and on the fact that their stories would be shown publicly, as tools for community training and awareness raising about local gender and health realities. Interested youth completed a short assessment to help them make informed decisions about whether or not to take part in the workshop and were offered multiple opportunities to talk with Sonke staff about the implications of sharing personal stories in video form. The project partners view these steps as essential, in an environment where HIV stigma continues to be prevalent and where issues like sexual violence and abuse are rarely discussed.

Training provided by Silence Speaks and Sonke staff during five weeks in October 2008 not only enabled participating youth to produce stories but also provided them with health education about gender and HIV and basic public speaking skills. Working with facilitators, the young people shared stories from their own points of view; listened to and discussed each other’s stories; recorded first-person voiceover narration; and generated photos and drawings with which to illustrate their work. Finally, Silence Speaks staff guided the participants through hands-on computer tutorials and supported them one-on-one in using a laptop to edit these materials into finished videos (Sonke maintains a traveling production lab for digital storytelling; each young person was assigned a computer for the duration of the four-day production component of the workshop).

Throughout the process, the Sonke and Silence Speaks facilitators talked with participants at length about what content and images they felt comfortable including in their final videos. The youth were asked to obtain explicit permission from those they wished to mention or show (in photos) in their stories; others decided, with facilitator guidance, that maintaining anonymity was appropriate. Facilitators also assisted the youth with linking their personal stories to broader social issues, as a way of ensuring that the narratives would reflect the roles of both individual agency and larger structures in identity development. Growing up in a country greatly impacted by oppressive apartheid legislation, youth were encouraged to highlight the complex interaction of factors that create obstacles in their everyday lives. As Alex de Wall and Nicholas Argenti explain, “we must see young people not just as victims of the misfortunes of Africa over recent decades, but as a powerful force for change” [2002:134]. His work points to the fact that youth both are victims of post-apartheid conditions as well as capable agents in constructing new possibilities for the future.

The eight students involved in the digital storytelling workshop produced stories covering a wide range of topics – from sexual assault, to living with HIV positive family members, to the dangers of drinking contaminated drinking water. After Tokozile decided to participate in the workshop, she approached a friend and “asked her to talk about it so it could help someone else who has been through the same thing.” As Tokozile explained, her friend “finally voiced out about it,” giving Tokozile permission to talk about the incident in a digital story (note: the girl’s identity is not revealed, to protect her privacy, 8/6/09). Here is an excerpt from the story script:

She found comfort in her boyfriend a few years ago. He used to listen to her -- he gave her the love and attention that she never got from home. She was at the tender age of 14, and he was 20 years old.

One day she and her boyfriend were taking a walk. He was asking her to visit his home. She asked, “Why do you want me to go there?” She did not want to go. He finally convinced her. Things got out of hand indoors. She tried to push him away, but he overpowered her. She lay there helplessly while he raped her. … she has never had the courage to report this case. She is afraid that the police will blame her for going alone to her boyfriend’s house. He still walks free, while she lives in fear of what he might attempt to do again. Justice has never been served.

Figure 2. Drawing by Tokozile, from her Story

During two weeks in August 2009, Amber Reedconducted an assessment of the Mhlontlo youth digital storytelling workshop. Methods included not only in-depth, open-ended interviews with the majority of participants but also a group story screening for and follow-up conversation between participants. The purpose of this assessment was to better understand the effects of story production on the participants as well as document possible recommendations for future Sonke youth projects.

In her interview, Tokozile discussed the friend she wrote about in her story and attributed changes in her friend’s behavior to the experience of having finally verbalized the previously untold story of the assault. According to Tokozile, the girl now serves as a peer educator in local schools, where she discusses the issue of rape with the goal of increasing awareness among young people.

A number of the other digital stories also demonstrate the potential positive results of speaking out about difficult life experiences and the pressures that young people in rural Eastern Cape Province face to conform to accepted norms of masculinity and femininity. One student, Kulile, described how Sonke’s focus on gender equality reshaped his attitudes about men’s and women’s roles in his community:

I thought okay fine, a man can cook, but it’s not important ritually. And when I met with Sonke my mind completely changed. I mean if you are surrounded by people who are stereotyping, you end up also stereotyping. They say if there’s only one potato rotten in a bag they all get rotten. And I don’t think I can ever stereotype now, because everyone is equal. What you can do, I can also do [8/6/09].

For his digital story, Kulile chose to write about gender roles in his community and personal life. This is demonstrated in an excerpt from his script:

When I went to high school, I used to cook full meals for my family. My new friends were impressed with what I was doing, they didn’t criticize me. We started competing, sharing recipes. We believed that the one who cooks best would attract ladies. We would bring the food we made to school. Girls would taste it and say, “Wow, it’s delicious, you are such a handsome guy, can you cook for me next week??” …

People in my village sometimes gossip about me, saying, “Uphakamile uyawuthanda umsebenzi wamontombazana.” (He is a high-class person, and he likes women’s jobs). But even when I came back from circumcision school in July, I did not change my views. I am living outside the box, being the kind of man I want to be, not the kind others want me to be. I live my life to be happy.

Figure 3. Photo from Kulile’s story

For many participants, the workshop was their first exposure to using computers. Along with the emotional and psychological benefits of digital storytelling, the project clearly demonstrated the value of exposing young people to new forms of technology and offering them training to which they would otherwise not have access. One participant said,“I’ve learned how to use a computer, it was my first time and I was excited when I saw it and I thought that it is going to be used by me. And I tell myself, inside myself, that this is the beginning of my life (sic)” (8/5/09).

Other students mentioned how they gained the confidence to speak in front of others as a result of the project. About a community screening of the stories that was held shortly after the workshop, one participant said:

I was never used to talking to a crowd…then we had to talk to the whole hall, a lot of people from different places, old and young. So I learned how to talk to people, how to address something that is a problem to someone else, and how to help others in things that they need help with. It’s very easy [now]! I can talk in front of school! [8/6/09].

Another student talked about how the digital storytelling project got him back on track at school, showing the potentially valuable influence this method can have on young people’s sense of self-efficacy and goals for the future:

I was drinking and doing such bad things…stealing some things off other people. So then I decided that when they chose me (to participate in the digital storytelling workshop) that, okay, it seems as if I am still a person who can succeed in life. Then I decided to change…they changed my life [8/7/09].

Overall the workshop assessment revealed that the combination of skill-building activities and the creativity of digital story production, along with the support of attentive and engaged facilitators, led to a continuum of positive impacts for the youth storytellers involved and for the larger community.

The most prominent criticism that arose during the project assessment related not to the workshop process but to the lack of community outreach that has occurred using the stories to date. Though participants felt extremely proud of their work, they were disappointed that more screenings hadn’t yet occurred. Tokozile speaks to this when she mentions that she has not yet seen any community-wide screenings of the stories:

…it would be helpful a lot. For like, young girls to talk, to not be afraid of certain things. It will help! It will help so that they gain knowledge of what is happening around them. So that things they can prevent, or things they can protect themselves from, they don’t do by learning from the stories that we did [8/6/09].

Tokozile’s comment brings attention to the need for adequate follow-up and support for digital storytelling projects. Though the participation itself builds youths’ sense of self-esteem and agency, facilitators have the ability to extend projects’ possibilities with structural support and plans for distribution of stories.

Another drawback to the program was the small sample size of participants; many stories were likely left unheard because funding and resources only allowed for eight participants. Nombasa highlights this in her interview: “I would choose more people, you know, to do it, not from only this community, from other communities, because there are schools not from here in town but in, in the rural area, so I’d choose those kids because most of them want to voice out but they cannot” (8/5/09). A pitfall of projects like the Sonke – Silence Speaks effort in Eastern Cape is that they do not represent ALL youth in a community; what voices are left unheard must therefore be questioned.

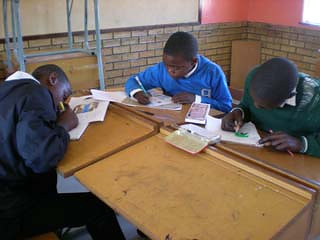

As part of a pilot project during August 2009 designed to explore the potential educational value of the Eastern Cape youth digital stories, Siyakhanyisa staff (a local HIV/AIDS support organization) and Amber Reed took the stories to several schools within the Mhlontlo Municipality, sharing them with students who were unfamiliar with the digital storytelling project or Sonke’s work. The goal of this endeavor was to further Sonke’s mission of using the stories as teaching tools and test the efficacy of screening and discussing them in a classroom setting. In two, one-hour sessions, students were introduced to the project and then viewed two selected stories as a group. Following the screening, students discussed the concept of human rights with facilitators and were asked to come up with their own version of a list of universal human rights – an exercise meant to foster dialogue about the difficult issues raised in the stories. In the last segment of these workshops, students were asked to create their own written stories, with accompanying drawings, using the digital stories they viewed as inspiration.

Figure 4. Students participating in a drawing project based on the digital stories.

One student in these classroom sessions described the experience of viewing the stories as educational and uplifting: “I’ve learned a lot of things. They’ve given me the strength, courage of saying what I feel for once, you know? Without people setting me back. They made me feel very emotional. I don’t know how…but they’ve brought courage and determination in me.”

These pilot educational sessions were also useful in highlighting the challenges that Sonke and local organizations face as they work for gender equality in rural areas, where particular attitudes about women and men are often deeply entrenched. One boy described how women in his community are lazy and “men are oppressed by the women here.” Widespread homophobia also presented a problem in discussions of equal rights for all people, with some students objecting to equality for LGBT individuals.

At the same time, using the Sonke digital stories in the classroom allowed students to talk about issues not normally addressed in school and gave facilitators an opportunity to increase dialogue, counter misunderstandings and assumptions, and provide accurate information on critically under-represented topics in the classroom environment.

The story-writing portion of these sessions also offered an inside view of the challenges and preoccupations faced by rural youth. The anonymous nature of the writing activity encouraged students to speak openly about otherwise taboo subjects and allowed facilitators to address the entire class during follow-up rather than single out particular students who may not have felt comfortable discussing sensitive topics. Writings focused on issues such as rape, violence, death, and despair:

Text: I have a friend her mother passed away and she doesn’t go to school. She was abused by her stepmother and her father has abandoned her and now she had nowhere to go (sic). The social workers took her and she ran away and now she lives everywhere.

Figure 5. Drawing by a girl, age unknown.

Another story directly begged for help against local violence:

Text: I am a girl of 16 years. I meet a guy which is too old he is wearing a black hat when I pass near with it, he told me to give him my bag I ask him that I can’t, he promise to kill me. I notice that this is a tsotsi (gangster) he take my bag off and he run away with it. I don’t know what can I do who can help me! (sic)

Figure 6. Drawing by a girl, age 16.

Such powerful cries for help can allow facilitators to identify and address gaps in the educational curriculum and advocate for the provision of appropriate services and health/law enforcement interventions outside of the classroom environment. Indeed, after this pilot study Siyakhanyisa staff made arrangements to regularly visit a local school to provide follow-up support to students on the issues raised during the classroom session.

The pilot study illuminated future work that Sonke and its partners can undertake, in adopting unique and engaging ways to train rural community members on how best to address critically under-emphasized issues for young people. Though the assessment showed the strength of using digital stories in the classroom, it also showed the importance of ensuring that adequate resources exist prior to conducting such educational sessions -- resources that are rarely available in rural settings like Mhlontlo. In their stories, many students expressed a lack of adults to turn to about difficult obstacles in their lives, raising ethical considerations about the value of using writing or creative arts to surface such obstacles in the absence of trained teachers, mentors, and counselors, and pointing to the responsibility of adults in the community to advocate for funding to support psychosocial assistance and justice for youth.

And yet the value of peer support cannot be overlooked. These pilot educational sessions made it clear that the benefits of the youth digital stories project in Eastern Cape reached far beyond the excitement and skill building imparted to the original eight workshop participants. In her interview, Tokozile explained that Sonke’s efforts in her community have encouraged her to gather friends and extend their ideals to other young people. She now travels with her friends around the community, seeking out those in need of gentle, peer-based emotional support for a variety of difficult issues. She describes an experience in this work:

There was this girl in class…she’s so quiet, she is so distant! She never says anything. So we, like, talk to her. She says that she’s afraid of people. And in class we look like people that she wouldn’t talk with and stuff…she’s afraid of what she can say, maybe won’t accept her for who she is and stuff (sic). But now she’s our friend! She’s like the most silly in class! She can talk, she can do whatever [8/6/09].

Another participant, Nombasa, sums up the goals of the digital storytelling project nicely in her description of her own story:

My story is about a woman standing up for herself. A woman talking for other women and trying to help the children in my community, and trying to tell all the people who’ve been involved in each and every pain that we must be strong and stay positive about whatever happens. We must also try to be free in our community and I’m telling those people who are abusing people, please let’s leave this and be a community. A community with love and freedom and peace [8/5/09].

The Sonke – Silence Speaks digital storytelling work with young people in Eastern Cape, South Africa shows that, when carried out with appropriate thoughtfulness and sensitivity, this unique participatory media production method can offer youth an opportunity to learn about new technologies, speak out against local challenges and hardships, and encourage young story viewers to give voice to their own life narratives. , and illuminate for adults in the community the ways in which the health and safety of young people are not being protected. The digital stories serve as clear evidence of young peoples’ desires to improve their communities. It is incumbent upon practitioners and researchers working in marginalized, resource-poor settings to attend not only to the individual emotional needs of youth but also to become engaged at the community/political level by advocating for structural changes which will provide viable housing, education, healthcare, and employment. Beyond the value of the youth stories as tools for peer education lies their potential for sensitizing local adult allies and public officials to the daily deprivations faced by Mhlontlo residents and moving them to take action towards building infrastructure and opportunity. This is the challenge facing Sonke as it moves forward into the next phases of its work in rural areas across South Africa.

Figure 7. Mhlontlo's youth digital storytellers

For more information about the digital storytelling project: Sonke Gender Justice Network: www.genderjustice.org.za/ info@genderjustice.org

Silence Speaks: www.silencespeaks.org / info@silencespeaks.org

Cruise, O’Brien, Donald B. (1996). Youth Identity and State Decay in West Africa. In Postcolonial Identities in Africa. Werbner, Richard, & Ranger, Terence, Eds. New Jersey: Zed Books.

Brodkin, K. (2007). Making Democracy Matter: Identity and Activism in Los Angeles. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Burgess, J. (2006). Hearing Ordinary Voices: Cultural Studies, Vernacular Creativity and Digital Storytelling. Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, 20(2).

de Waal, Alex & Argenti, Nicolas (2002). Young Africa: Realising the Rights of Children and Youth. Trenton: Africa World Press, Inc.

Lambert, J. (2002). Digital Storytelling: Capturing Lives, Creating Community. Berkeley: Digital Diner Press.

Hinyard, L., Kreuter, W. (2007). Using Narrative Communication as a Tool for Health Behavior Change: A Conceptual, Theoretical, and Empirical Overview. Health Education & Behavior, 34(5).

The term “digital storytelling” is used to describe a variety of media production practices and media forms. For purposes of this article, the term refers to practices originated at the U.S.-based Center for Digital Storytelling, www.storycenter.org.

A careful informed consent protocol was followed, with confirmed workshop participants obtaining written parental permission before creating their stories and signing a story release form at the conclusion of the production session.

For more on Sonke’s work with Digital Stories and to view selected stories, visit www.genderjustice.org.za/projects/digital-stories.