Assistant Professor

Department of Telecommunication and Film

The University of Alabama

Email: rramist@ua.edu

Ph.D. Candidate

Department of Curriculum and Instruction

University of Minnesota

Email: doer0026@umn.edu

Associate Professor and Chair

Department of African American & African Studies

University of Minnesota

Email: wrjacobs@umn.edu

In the fall of 2008, Rachel Raimist and Walter Jacobs collaboratively designed and taught the course “Digital Storytelling in and with Communities of Color” to 18 undergraduate students from a variety of disciplines. Candance Doerr-Stevens audited the class as a graduate student. This article examines the media making processes of the students in the course, asking how participants used digital storytelling to engage with themselves and the media through content creation that both mimicked and critiqued current media messages. In particular, students used the medium of digital storytelling to build and revise identities for purposes of rememory, reinvention, and cultural remixing. We provide a detailed online account of the digital stories and composing processes of the students through the same multimedia genre that the students were asked to use, that of digital storytelling.

Keywords: digital storytelling, identity, media literacy, pedagogy

“Digital Storytelling in and with Communities of Color.” Storytelling is a tool for preserving memory, writing history, learning, entertaining, organizing, and healing in communities of color. It is in the telling of stories that communities build identities, construct meaning, and make connections with others and the world. In this course we will investigate modes and power dimensions of digital storytelling, analyze the role of digitized media as a method of individual healing, and examine media as tools for community organizing and development. We will explore media making, creative writing, and memoir in both literary and digital writing, and examine the gendered, racialized, and classed dimensions of digital storytelling. We will create projects to tell our stories, examine our social ghosts, and work with community members as part of the 40th Anniversary of the African American and African Studies Department to develop digital stories about Twin Cities communities of color. Students will learn to produce creative work (writing, video, photography, sound, and artwork) and gain technical proficiency in Mac-based editing. Students will produce photographic and video work that will be shared on the course blog. No technical expertise is necessary!

(Course description for “Digital Storytelling in and with Communities of Color” undergraduate class, University of Minnesota, fall 2008.)

In the 2005 book Speaking the lower frequencies: Students and media literacy Walter Jacobs investigated strategies for encouraging undergraduate students to become critical consumers of the media without losing the pleasure they derive from it (Jacobs, 2005). In The Communication Review “Media literacy and the challenge of new information and communication technologies” article, however, Sonia Livingstone notes that in the digital age literacy should provide students with “the ability to access, analyse, evaluate and create messages across a variety of contexts” (Livingstone, 2004, p. 3). In other words, students need to become producers of media content in addition to being critical consumers of media worlds.

Media theorists have argued that a focus on media production must be at the center of any critical media curriculum in order to foster perspectives that cannot be developed through analysis alone (Fabos, 2008; Kellner, 2004). Yet in focusing on the production practices of media, pedagogy must attend to the particular conditions and contexts that shape how media producers negotiate their production practices between social reproduction and critique (Hill & Vasudevan, 2008). In a new project Rachel Raimist, Candance Doerr-Stevens, and Walter Jacobs explore this expanded understanding of media literacy. Our book-in-progress Speaking the lower frequencies 2.0: Race, learning, and literacy in the digital age examines pedagogy and literacy through theories and practices of digital media making, specifically digital storytelling.

Speaking the lower frequencies 2.0 is a collaborative interdisciplinary project. Jacobs – a sociologist interested in critical pedagogy and popular culture – connected with media maker and feminist scholar Raimist, who was a graduate student at the time. They decided to develop and co-teach a course that fused questions of media, storytelling, and identity; “Digital Storytelling in and with Communities of Color” was cross-listed between the Department of African American & African Studies and the Department of Gender, Women, and Sexuality Studies. Doerr-Stevens, a graduate student interested in literacy and learning in the digital age, audited the class, and was invited by Raimist and Jacobs to be a research collaborator.

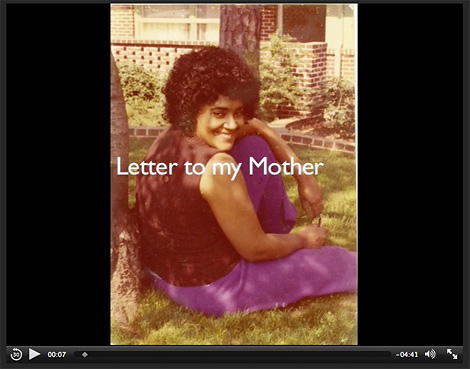

The epigraph to this section provides an overview of the main elements of the fall 2008 “Digital Storytelling in and with Communities of Color” course. In the course the students read Jacobs’ memoir Ghostbox (Jacobs, 2007), and discussed it with him in class. Students also watched and critiqued a digital story representation Jacobs made at the Berkeley, CA Center for Digital Storytelling (CDS) in May, 2008. (His digital story “Letter to my Mother” may be viewed at http://tinyurl.com/JacobsDS/ ).

Figure 1. Picture from the story Letter to my Mother.

In these and other discussions, students explored the CDS social processes of digital storytelling (Lambert, 2006). For example, students learned that it takes courage to share their stories publicly; they risk judgment from others. But once they develop confidence and commitment to the storytelling process, students can generate many new insights related to media production as a vehicle for engagement with culture identity work through producing short videos and by remixing and repurposing existing media content to tell new stories. Raimist and Jacobs expanded the CDS model of digital storytelling into a critical process where students were taught not only the technical skills necessary for creating and sharing their own digital stories, but also were provided with a framework they could use to interrogate themselves and engage with other contexts for purposes of responsive content creation.

To lay the foundation for this framework, the students evaluated written texts such as “In our glory: Photography and black life” (hooks, 2003), “Chicana/o artivism: Judy Baca’s digital work with youth of color” (Sandoval & Latorre, 2008), and Cybertypes: Race, ethnicity, and identity on the internet (Nakamura, 2002), and also analyzed many online digital stories. In reading and viewing these texts, we examined issues of media ownership and the power of media content to represent multiple truths. We asked students to consider how these media truths have shaped their own identities. Building on Livingstone’s (2004) focus on content creation as a route to media literacy, we then asked students to explore their own stories and thus contribute their own truths to the larger media mix through the process of digital storytelling.

An essential element of the digital composing process was the “Story Circle.” Based on a component of the 3-day CDS Standard Digital Storytelling Workshop Jacobs attended, the Story Circle is an in-class workshop where students share their story ideas and get feedback from others in the class. The ground rules of the CDS Story Circle were: (1) let each person present to the end without interruption; (2) give an affirming comment as the first response to a participant; (3) frame critical feedback with the construction, “If it were my story, I would…”; and (4) assertive folks should try to let the more shy participants speak first. We added a fifth ground rule when we used the Story Circle technique in our “Digital Storytelling in and with Communities of Color” class: (5) while some stories may appear to be more “serious” than others, they all reflect the speakers’ truths, so don’t judge them against one another. In adding this fifth rule, we intended to create a space for students to begin resolving the various tensions involved in the conflicted cultural and identity-based work of digital storytelling.

After the Story Circle the students went through the process of building their digital stories with extensive feedback from the instructors and from each other. To amplify the sense of audience involved with digital storytelling, the students were then required to post their digital stories to a public blog, and provide comments on fellow students’ digital stories. The blog also drew commentary from the students’ families and friends, as well as feedback from the general public. The blog, which served as a public forum, may be accessed at http://blog.lib.umn.edu/afroam/storytelling/.

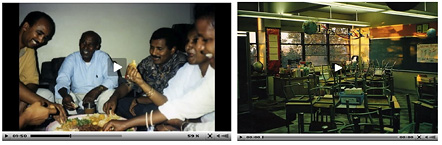

In light of bell hooks’ description of memory and re-memory as redemptive, we encouraged the students to see their storytelling as self-affirming and potentially liberating (hooks, 2003). For some students, digital storytelling became a process of synthesis, in which the students made sense of their stories through a deliberate sorting of multimodal content (Lambert, 2006). For others the process was one of self-definition in that play with elements of narrative and visual expression allowed for identity revision (Lundby, 2008). In both cases the process of storytelling was one of “vernacular creativity” (Burgess, 2006) in which the students transformed their own everyday stories into a “shared public culture” (p. 210), one that creates a space for sorting through conflicting media messages while also forging new possibilities for seeing themselves and others. The students’ digital stories can be viewed online: http://tinyurl.com/UMstories/.

Figure 2. Pictures from students’ stories.

Drawing on the expressive potentials of multimodal storytelling, we too have created a digital story on “The Pedagogy of Digital Storytelling in the College Classroom” to more extensively share our thoughts on how a college class on digital storytelling can help students expand understandings of themselves and their roles in communities inside as well as outside of the university. Just as we asked our students to critique media through making media that talk back, we use the storytelling modes of image, motion, music, and voice to examine what it means to embrace media creation in the classroom. Our online presentation, thus, is both an example of a digital story and is an exposition on digital storytelling as a route to media literacy in the digital age. To view “The Pedagogy of Digital Storytelling in the College Classroom” digital story go to http://tinyurl.com/DSpedagogy/.

According to Leslie Rule’s oft-quoted definition, “Digital storytelling is the modern expression of the ancient art of storytelling. Digital stories derive their power by weaving images, music, narrative and voice together, thereby giving deep dimension and vivid color to characters, situations, experiences, and insights” (Rule, 2009). By the end of the semester, the students in the fall 2008 “Digital Storytelling in and with Communities of Color” class at the University of Minnesota were well versed in the power of digital storytelling in a university setting. In sharing our experiences, we invite readers from places throughout the educational spectrum to explore how they may similarly help their students develop strong voices and create digital stories as tools to more fully comprehend complex lived realities.

Burgess, J. (2006). Hearing ordinary voices: Cultural studies, vernacular creativity, and digital storytelling. Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, 20(2), 201-214.

Fabos, B. (2008). The price of information: Critical literacy, education and today’s Internet. In D.J. Leu, J. Coiro, M. Knobel & C. Lankshear (Eds.), Handbook of research on new literacies (pp. 843-874). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hill, M.L. & Vasudevan, L. (2008). Media, learning, and sites of possibility. New York: Peter Lang.

hooks, b. (2003). In our glory: Photography and black life. In L. Wells (Ed.), The photography reader (pp. 387-394). New York: Routledge.

Jacobs, W. (2007). Ghostbox: A memoir. New York: iUniverse.

Jacobs, W. (2005). Speaking the lower frequencies: Students and media literacy. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Kellner, D. (2004). Technological transformation, multiple literacies, and the re-visioning of education. E-Learning, 1(1), 9-37.

Lundby, K. (2008). Digital storytelling, mediatized stories: Self-representations in new media. New York: Peter Lang.

Lambert, J. (2006). Digital storytelling: Capturing lives, creating community (2nd ed.). Berkeley, CA: Digital Diner Press.

Livingstone, S. (2004). Media literacy and the challenge of new information and communication technologies. The Communication Review, 7(3), 3-14.

Nakamura, L. (2002). Cybertypes: Race, ethnicity, and identity on the internet. New York: Routledge.

Rule, L. (2009). Digital storytelling. Retrieved from http://electronicportfolios.org/digistory/

Sandoval, C., & Latorre, G. (2008). Chicana/o artivism: Judy Baca’s digital work with youth of color. In A. Everett (Ed.), Learning race and ethnicity: Youth and digital media (pp. 81-108). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

“The Pedagogy of Digital Storytelling in the College Classroom” digital story: http://tinyurl.com/DSpedagogy/

“Digital Storytelling in and with Communities of Color” blog: http://blog.lib.umn.edu/afroam/storytelling/

“Digital Storytelling in and with Communities of Color” digital stories: http://tinyurl.com/UMStories/

“Letter to my Mother” digital story: http://tinyurl.com/JacobsDS/