A competence meeting is an arena for shared knowledge production. This approach does not offer supervision, teaching or decision-making, but rather an arena for reflection. Students are required to use their everyday knowledge when they reflect on theory and practice, and the interconnection between these two. Competence meetings, usually lasting for one hour, include both digital and traditional classroom-based learning activities. This article discusses the use of competence meetings within educational programmes. Attached to this article is an example of a competence meeting: An interview with Professor Tom Andersen and a follow-up discussion between professors and practitioners in Iceland, South Africa and Norway.

Practical reflective methods may help students to use their practice experiences. Using competence meetings is one way of bridging the gap between theory and practice. There is a need to develop tools that strengthen the students’ abilities to analyse and create a critical perspective based on everyday knowledge (Schutz 1972/2005). Questions and new thoughts are more important than answers when students are asked to draw on their experiences to illuminate theory, or when they embark on reflective processes regarding their own or others’ practice experiences.

The reflective approach recognises that theory is often implicit in the way professionals act and may or may not be congruent with the theory they believe themselves to be acting upon. This type of theory, or perhaps “practice wisdom”, is developed directly from practice experience – a “bottom-up” type of process. (Fook 2002:39)

Social work has its origin in practice, and competence meetings mainly rely on the students’ own practice. Sometimes other practitioners, who are not a part of the study programme, also contribute to these meetings. Since the beginning in 2003, the flexibly delivered master’s degree in social work at Bodø University College has had compulsory parts to it such as international work requirements, book reviews and competence meetings in addition to ordinary examinations (Oltedal 2006).

A competence meeting is an arena in which people can participate in the production of knowledge by describing contextual practices. The concept developed as a negation, and was neither supervision, teaching, nor decision-making, but rather an arena for reflection. Another aspect of the creation of competence meetings was an interest in validating practice, and this approach could be an alternative strategy to the emphasis on theory in the social sciences. For students to receive credits for a competence meeting, it is a requirement that they are evaluated and receive feedback from other participants. This puts the students in a new practice situation that is quite unusual for ordinary work life. They need to reflect upon and communicate their own reflections about what has occurred.

The aim of this article is twofold:

To describe a competence meeting as part of a flexible, delivered study programme.

To engage in a theoretical discussion on what a competence meeting is.

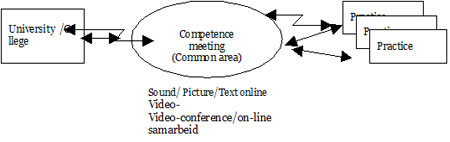

A competence meeting can be characterized as blended learning. Littlejohn and Pegler (2007) define this type of learning as a blend between “real” and “virtual” domains, between on- and off-campus activity, between online tasks and between face-to-face learning activities. E-learning allows us to also blend different spaces and work across time zones and geographical spaces in real and asynchronous time. In a South African context, the implementation of blended learning activities within a social work programme follows a policy shift from teaching to an active learner-centred pedagogy (Bozalek 2007). This approach creates considerable opportunities for participation and collaboration among students. They were challenged to explore their preconceived thoughts when working with tasks that had no right or wrong answer. An emphasis was put on reflection and how to account for different statements, as in this case, when they explored ethics within social work (ibid).

Internet access is generally good among Norwegian students, and the use of ICT in Norwegian flexible education depends on the study model and the students’ study context (Rønning and Grepperud 2006). E-mail is the most common channel of contact between students and teachers, and digital communication is an important supplement for the flexible student (ibid). It is a challenge to develop more contact among students and a competence meeting, as I am discussing in this article, is one way of creating such contact. Within such meetings, students need to meet face-to-face in “real” or “virtual” rooms and document an online meeting in writing.

As an example, it is a challenge in theoretical studies within social work to help students to identify life experiences that help them to transfer theoretical concepts from one context to another. On the other hand, theories help students to be able to identify and express knowledge from everyday life. In problem-based learning approaches, students learn how to learn (Bjørke 1996). Knowledge becomes more grounded and is easier to transfer to new situations, since the students have been active learners both in the integration of theory with their own practice and/or when they have been drawing on practical experiences in developing new perspectives.

In a competence meeting, it is important to create a reflective process, and students need to draw on their own experiences while studying a subject like social work. Discussing articles can be one way of creating a group process in a competence meeting. The teacher or leader of the competence meeting needs to choose an article which triggers discussion and perhaps helps to explore contested issues. The following is an example of a task in which bachelor students in social work were asked to reflect upon links between theory and practice. The students read an article where the main finding concerned the advantages of working in groups without having a teacher as a group leader (Innjord 2006). After the students read the article, each of them, either individually or as part of a group, was instructed to write a paper consisting of two parts. Their taskii was as follows:

“After reading the actual article, write a paper consisting of the two following parts:

Write a résumé of the text with the author’s main perspective as the point of departure. Try to write in such a way that it can be understood by a person who has not read the original text. To take the author’s perspective is not just to write a short version of the text with the author’s own words and expressions. On the contrary, you have to try to convey the author’s message and give arguments based on the premises of the author. You choose the form of presentation yourself. For example, you can write a letter to somebody you know well or you can dramatize a situation with different role players, where the author has one role and presents arguments for his/her message.

This part consists of your own reflections initiated by the former text and former presentations of this text. You are expected to provide more than common statements like “this is an interesting text“, “the author is biased” or “this is an incomplete analysis”. You need to account for your arguments and reasoning. This can only be done by delving into the author’s reasoning and taking it seriously. It is also valuable if your own reflections raise questions and reflections regarding your profession, or future everyday work. It is useful to try and draw parallels to something else you have read, written or participated in.”

The last sentence is especially important to highlight in that students are challenged to draw on their own experiences from something they have participated in. This will change the discussion from a question of the right or wrong way of how to interpret the author’s purpose for writing a text, towards a discussion on their own interpretations and associations. One of the aims of the competence meetings is to create a subject-to-subject relationship in which something is being explored. It is not of great importance to reach a conclusion at the end of the meeting. When students from various contexts are comparing perspectives, it is possible to illuminate how the same phenomenon is represented in different ways within each context, thereby challenging the doxa of what is taken for granted. The above task helps students to cross the learning context between practice and theory, where first, they must explore another person’s (the author’s) premise and second, interpret and make relevant those phenomena and concepts within their own context.

From a studio in Durban, South Africa, a professor of social work and leader of an international standards committee regarding programmes in social work gave a presentation of this type of work. Simultaneously, in Bodø, Norwegian and international students were gathered in a room, while the student who facilitated the meeting communicated by telephone from his home on Senja, an island north of Bodø. The teacher present in the room helped to coordinate the meeting and discussion among participants who were located in three different places. Another example is from a student who conducted an informational meeting on childcare as part of her work in a local municipality. In her report, published in the learning platform Fronter, she documented her experience of talking with a local nurse and the headmaster at the primary school in regard to issues related to interdisciplinary collaboration. A third example is from a student who reflected on how to deal with and document fervent issues from his practice as a social worker, and who invited colleagues to be part of the meeting. Thus, a compulsory part of a master’s programme can have consequences for the practice field, thereby making an impact.

A student who wished to discuss an intense case about how a professional social worker deals with suicidal patients had invited a minister from a hospital and a cooperative partner, in addition to fellow students, to a competence meeting. All these participants drew on their experiences as laypeople and professionals. In this way, the competence meeting provided quite a bit of input from the practice field.

What type of input did the meeting receive from the university college? It is possible that the most important input came from a platform opened by the university college to help validate the knowledge production of the competence meeting, in order to accredit it as a necessary part of the master’s diploma programme in social work. Social work is mainly invisible work (Pithouse et al. 1998), as social workers meet with clients without being observed by colleagues. The result of a social worker’s intervention is uncertain and ambiguous, and practitioners are not usually held accountable for the helpful or restrictive processes in which they are involved. One way of opening up the practice of social work is to account for assessments and decision making in tense situations in which circumstances, contexts and personal histories require reflection. When social workers visit clients’ homes, for example, the analytical focus must transcend the division between life and system worlds, and contain an authoritative practice based on negotiations in local places, such as with the family (Sagatun 2008). Complexity in such everyday life creates a self-contradictory knowledge, disconnected from strict plans and only partially made clear (Schutz 2005). In issues regarding tense situations, a social worker cannot rely on instructions, but instead needs to use practical wisdom. Since the meetings are recorded and stored through a video conferencing system, the reflective process of social work can be studied more in-depth by thoughtful consideration as the participants go back and study the accounting process in the discussion of specific competence meetings.

Let us have a look at how a competence meeting is defined and structured as presented in the study plan for this compulsory part of the master’s programme:

Goals for competence meetings:

To provide a forum that may develop advanced professional practice;

To create areas of contact between theory and practice (education and places of practice);

To develop places for improving practices. To offer master’s students a forum for reflection, and develop theory based on practice experience or in connection with a master’s thesis;

To contribute to the international development of practice and education;

To utilize and develop competence linked to multimedia activity.

Content:

The subject will be given an opportunity for systematic reflection on professional daily life and professional knowledge in welfare work through practice and different study situations. To be a professional concerns knowing the possibilities and limitations of one’s competence, and to be able to face that level of competence in practice. It is in relation to others through experience with concrete situations that an individual can acknowledge his or her professionalism.

The goal is for students, by participating in a competence meeting, to gain an increased understanding of the dynamics between theory and practice, by studying professional daily life in regard to welfare work. The focus is on critical and ethical reflective work with experiences from practice and the contemporary challenges of society.

Form:

The one who is responsible for the master’s programme will arrange a series of competence meetings in which each master’s student may present a particular case for discussion. Practitioners from a multitude of professional backgrounds will participate and provide a mechanism for development in the advanced practice of social work, thereby promoting a closer association among national and international students, and the local professional practice.

A competence meeting is an encounter within a group of people who decide to reflect upon an actual theme or aspect of their work and/or practice experiences. One person takes responsibility for presenting an introduction and leading the discussion. Some are responsible for actively participating, while others evaluate the process afterwards together with the leader of the meeting.

Documentation:

For a meeting to be accredited, a student needs to document the learning process with the following:

A statement of when and where the competence meeting is held.

A description of how many participants are involved in the meeting and which institutions are represented.

A presentation of the agenda for the meeting.

An evaluation of the meeting by two of its participants (either orally or in writing).

An evaluation of the three phases of preparation, meeting and reflection after the meeting.

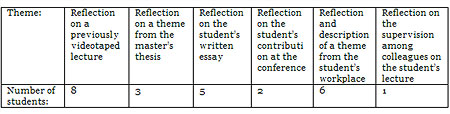

Masterforum is a communications room for Fronter, an ICT platform for teachers and master's students in social work at Bodø University College. On December 13th 2007, a total of 104 master's students were registered and 25 published a documentation of the competence meeting in Masterforum. When categorizing the content and theme of these meetings, the following six different groups appeared:

Table 1: Content of master's students' competence meeting.

As we can see from the table, the themes varied. Eight students presented an introduction to discussion by using a videotaped lecture such as “Symbolic Interactionism” or “Relational Ethics”. These videotaped lectures were available in Fronter for all master’s students. Six students used the opportunity to arrange a meeting with colleagues and collaborative partners to discuss a work-related issue. One student, who was working at a university college, used the competence meeting as part of a compulsory student evaluation of her own lecture. Five students presented an essay that was an exam paper on a social work theory course in the master’s programme. These essays were personal accounts that inspired further discussion among the students. Nine such student essays from the master’s programmes in social work and practical knowledge are published in the book, “A Glance at Practice” (Blikk på praksis), in which social workers narrate their work experiences (Olsen and Oltedal, eds. 2007).

The number of participants in the meetings varied. On one occasion, there was only one student, the teacher and one of the technical staff in the room, while three students were logged onto the streamlined video conference and one was logged onto a chat channel. Students who presented issues from conferences, or described an issue from their work situation, usually had many more people who attended their presentations (between 10 to 60 people).

The flexibly delivered master’s programme has many off-campus students, and as a result, there is a need to enhance even more interactive activity and to develop educational forms that increase contact between students living in different locations.

In the following, I will present a competence meeting between professors and practitioners in three countries. This meeting was arranged in connection with the publication of this article, and is available as a video link attached to this article. It consists of an interview that the leader of this meeting, Thorhildur G. Egilsdottir of Iceland, had with Professor Tom Andersen on October 10th 2006 and of a virtual meeting on May 13 2009 between participants in Bodø, Reykjavik and Cape Town.

The leader of the meeting has written the following documentation:

An online competence meeting between Iceland, Norway and South Africa on May 13th 2009.

Participants:

From Reykjavik: Thorhildur Egilsdottir, Bjarney Kristjansdottir and Dr. Sigrun Juliusdottir.

From Bodø: Pål Grav, Reidun Ulvin and Sigurd Schultz.

From Cape Town: Dr. Vivienne Bozalek and Dr. Tamara Shefer.

The purpose of the meeting was to reflect on an interview with the world renowned family therapist Tom Anderson. Thorhildur Egilsdottir, the leader of the meeting, interviewed him while he attended the 15th World Family Therapy Congress of the International Family Therapy Association (IFTA) held in Reykjavik, Iceland on October 10 2006. In the interview, he was asked to reflect on three different realities: a) the non-moving and the visible, b) the moving and the visible, and c) the moving and the invisible. The link with this part of the interview was sent to all the participants two weeks in advance of the meeting.

The preparation

The idea of this particular competence meeting came from Dr. Siv Oltedal. The interview was presented at a competence meeting in the fall of 2006 at the University College of Bodø. Dr. Siv Oltedal provided e-mail addresses for one of the African participants and one of the Norwegian participants. They were then asked to invite participants from their country and I also invited two Icelandic colleagues. Although the term "competence meeting" was a new concept for most of us, this was no hindrance to participation. Finding a suitable date when everyone was available was a challenge. Several options were checked before we finally found the perfect match for everyone. Due to different time zones, we agreed to start as early as possible, i.e. at 8 am in Iceland and 10 am in Norway and South Africa. Preferably, we should have watched the interview together, but technically, this was a rather difficult task. I therefore decided to have the interview available through an internet link that was sent to all participants two weeks in advance. Thus, they could watch the video at their own convenience.

The meeting

The meeting took place online, but we were sitting in three different countries in three different studios. There were eight participants: Thorhildur Egilsdottir, Social Worker in Reykjavík; Bjarney Kristjansdottir, Social Worker in Reykjavik; Dr. Sigrun Juliusdottir, Professor of Social Work at the University of Iceland; Pål Grav, Social Worker in probation office in Bodø; Reidun Ulvin, Social Worker in probation office, mid-Norway; Sigurd Schultz, Social Worker and Head of Open Prison in Bodø; Dr. Vivienne Bozalek, Professor of Social Work, University of Western Cape Town; Dr. Tamara Shefer, Professor of Gender Studies, University of Western Cape Town. There were also three technicians: Grettir Sigurjónsson, University of Iceland; Jørgen Karlsen, University College of Bodø, and Graham Julies, University of Western Cape Town. The meeting lasted for approximately one hour. Though we had not met previously, we immediately established a good atmosphere while reflecting on Tom´s reflections. We related Tom´s reflections to our practice as social workers in addition to being teachers and researchers. We managed to meet and understand each other across countries and contexts. All the participants agreed that attending the event was a good experience.

The aftermath

It was enjoyable to arrange the meeting and experience the impact this method had on the participants. Thinking back to the meeting and the ideas expressed there, I somehow feel my thoughts/ideas/opinions are not the same as before. Sharing practical experiences across different countries and cultures is a knowledge-building process geared to breaking down preconceived ideas. The joy and the laughter at the meeting was the best part of the process and tells us a lot about the possibilities that the internet may hold for teaching and developing social work in the future.

Reykjavík, May 24th 2009

Thorhildur Egilsdottir

The inspiration to develop a competence meeting as a practical reflective method can also be traced back to thoughts about the reflective process and reflective team (Andersen 1994). The book "Innovations in the Reflecting Process" (Anderson and Jensen, eds. 2007) honours Tom Andersen's courageous, creative and committed contributions. The book demonstrates how his ideas have created worldwide development in the field of family therapy. In the preface of the book, the editors write: "Some have made footprints that will last for a long time. One of these is Tom Andersen. From a position as a professor of social psychiatry in northern Norway, he has moved around the world participating with other professionals in their efforts to develop their work and seek wider horizons" (ibid). Tom Andersen died on May 15th 2007 and Michaelsen writes the following memorial describing Andersen's perspective: "In meetings and conversations, we find our hope. When we are listening, seeking words and describing ourselves, we inform ourselves and others. Thus, we can see what we see, hear what we are hearing and move forward in life. (...) Listen and see what is being said. Here are the answers and the questions."

"We have to respond to what people say and not to what we think they are saying" says Tom Andersen in the attached videotaped interview. He wants to explore what is reality and how people meet each other on the surface. It is important to see and to listen. Participants in the competence meeting from Norway and Iceland had all met Tom Andersen in real life. Sigrun Juliusdottir says that before she delivered a speech at the above mentioned conference in Iceland, she told Tom Andersen that she was very nervous. He then he replied: "I do not think so much." We can interpret this answer to be in accordance with his general perspective in which he focuses upon seeing and hearing.

Although the participants from South Africa were not familiar with the thoughts of Tom Andersen, they say that it resonates with their experience that language shapes meaning. An important question is: How do we really listen to people coming from different realities? However, as one person from South Africa says: Social workers are going to help people to think about what they can do, although it is perhaps naive to think that voices in themselves will do anything. To be able to create knowledge and understand this new information, it must contain a suitable difference in regard to what people are already familiar with; the new information must not be too common or too different from what the audience already knows (Andersen 1994). In a competence meeting, a Norwegian participant used the metaphor about how social workers should act as troublemakers within their workplaces. The challenge is to then find the right distance between what you and others think, thus enabling one to be able to contribute to development. In a competence meeting, the person who presents the introduction shares something that he/she has struggled with, or explores the connection between theory and practice. Interactions and reflection should be given time so that participants may experience both an inner and an outer conversation (ibid). This method is more about spreading a great deal of seeds and creating a difference that makes a difference (Bateson 1972).

Participants were very excited about the possibility of using video conferencing, and for some of them it was their first video meeting. What follows are some more comments from the participants at the end of the meeting:

It felt like a very good experience. I was grateful to be able to participate in a competence meeting and be involved in discussions across contexts. It was demonstrated for the participants that language is a tool as well as a hindrance. The description of the possibilities created by technology and internationalization was wonderful (Iceland).

One wondered about where such a meeting would take the participants. His reply was: Maybe it is about human beings meeting other human beings? (Norway).

A participant found the conversation interesting because it speaks to her research and theoretical interests. She says it was good to see an image, knowing that the person is there. She was quite inspired to see what the visual adds to the conversation (South Africa).

It was a rather comprehensive job to set up the meeting by adjusting in the technical equipment. The technician in Bodø used equipment that was splitting the video signal from the decoder, using a device which transforms encoded signals into their original form; thus, one was directed toward the monitor and another toward the recorder. The same splitting procedure had to be done with the sound signals. He made two simultaneous recordings. One was stored in the server, and was sent directly in real time to the participants at the meeting. The other recording, which was of higher quality, started earlier than the other one. It is the last one that Thorhildur, the leader of the meeting, was editing for the final version of this competence meeting.

The flexible master’s programme in Bodø draws its candidates from all over Norway and, in some cases, from other Nordic countries. The curriculum has a flexible form, and makes comprehensive use of streaming for lectures. This makes it possible to complete the master’s programme as an off-campus student.

In December 2007, an invitation to participate in reflections upon competence meetings was first posted in the Masterforum information area. Thereafter, informants who had participated in several meetings received an additional mail. I received few replies. In spite of this, I decided not to send new reminders because I had received replies representing the following three categories: teachers, on-campus students and off-campus students. The aim of this assessment was to get a qualitative, explorative overview of this method, rather than a generalized opinion based on a quantitative approach representing all the participants. Using a qualitative approach, it is sufficient to get one answer from each of the three informant categories. Different answers from these three informants are presented and discussed. It is reasonable to suppose that the chosen informants represent some of the most engaged participants involved in the competence meetings. The informants mailed me answers on the following questions:

How would you describe a competence meeting?

What are the benefits and challenges provided by this kind of educational practice?

How may competence meetings be improved?

When our informants were asked to describe a competence meeting, they all emphasized that students involved in such meetings play a more active role than they do in other parts of the master’s study programme. The leader of the master’s programme focuses on the fact that such a meeting is an arena for students to take the lead in presentations and reflections on the subject under consideration, while the teachers play a more passive role. The on-campus student describes it as a lecture held by a student with an audience of other master’s students, aimed at mediating theoretical knowledge and knowledge developed in practice.

“To share creates a feeling of being part of a context, and such meetings are inclusive.” This was the immediate reflection shared by an off-campus student when she was asked to describe her experiences from competence meetings at Bodø University College. She also wrote: “What makes a competence meeting different from other meetings is that it has a more open structure, thus creating new perspectives and challenging prejudiced opinions. Open processes that take place in the gathering are crucial within a competence meeting.”

This off-campus student also emphasized that the process of preparing, implementing and reflecting on the meeting does more than build knowledge; it creates a feeling of coping and connecting with other students as well. Her opinion is that such processes are very difficult to produce in other ways within a distance-education programme. On the other hand, she says that it is not fruitful for further discussion when students repeat lectures that are taped and already available to all students.

A prerequisite for a competence meeting is that a group of people participate. In this way, the off-campus student highlights the importance of recruiting participants to take part in competence meetings. If there are too few students, the person who gives the introduction becomes too important, and many questions are directed to this person. As a result, it almost becomes like a traditional lecture in which the teacher is the expert. According to the off-campus student, the necessary dynamic in a competence meeting then disappears.

When the on-campus student expresses what is positive, she underscores the new experiences and learning that result from presenting an introduction that can contribute to reflections regarding practice. It is a new and exciting form of education. She says it is a good way of learning because you can also learn from what fellow students consider to be important. However, on the down side, there were often too few students participating, so the dialogue did not always take off. In a situation where the video conferencing system was not functioning, the leader of the competence meeting communicated by telephone. The distance between on- and off-campus became evident, and the on-campus informant highlights the fact that it is necessary to ensure technical equipment which creates a common communication room in real time.

The leader of the course emphasizes that it is a positive that students take a more active approach to this subject. He says that it is especially important that students who are presenting at the meeting accept the fact that the teacher does not take responsibility for creating discussions. However, the leader agrees that there are too few participants on the internet, and therefore the meetings depend on the four to five students present in the classroom.

Seen from the off-campus student’s perspective, a competence meeting breaks the isolation of the individual student. Isolation is the main disadvantage of being a distance-education student. Competence meetings create an opportunity to develop an internet milieu, with the possibility of using a web camera to make direct contact with fellow students and teachers. She says it feels like being on campus when this type of communication is occurring in real time. In her opinion, the biggest challenge - the lack of community - could be dealt with by developing a competence meeting as a better reflective practical method:

“Students may carry out the meetings alone or together with other students. This is possible to do in different ways, like creating a net connection between different parts of the country, having a conversation with a relevant, skilled person/professional followed by a reflection upon this conversation, or by taping a discussion among students followed by a reflection on this discussion. In this way, you get reflections upon reflections and you will break up the two-way communication between presenter and audience. Circular processes are important in education because the individual will be involved in a way that creates attachment and gives the student a feeling of belonging to a community. Creating these processes is the biggest challenge for the future of distance-education.”

“More focus on practical experiences”, the on-campus student said when she was asked to comment on how competence meetings can be improved. The leader of the master’s programme and the off-campus student both underscored different ways of creating more collective processes by challenging students to work together in groups. For example, in 2007, on-campus students took responsibility for four different meetings, and inspired each other by switching the role as leader, evaluator or audience member in the meeting. According to the teacher and the off-campus student, the teacher does not necessarily need to be part of the meetings.

Learning theories can be individual, collaborative or cooperative. Regarding the first, education is conducted alone, while the second depends on a group, and the third takes place in a network (Paulsen 2008). Individual learning dominates traditional online distance-education, and the cornerstone for the development of cooperative learning is voluntary but attractive learning communities, while traditional face- to-face institutions favour collaborative learning in which individual flexibility needs to be limited and students learn to sink or swim together (ibid).

The Theory of Cooperative Freedom claims that adult students often seek individual flexibility and freedom. Therefore, there is tension between the urge for individual independence and the necessity to contribute in a collective learning community. Morten Flate Paulsen (2007) has based his theory on the following three pillars:

Voluntary, but attractive participation.

Means promoting individual flexibility.

Means promoting affinity to a learning community.

Does a competence meeting fulfil these three pillars? If you register for a study programme, it is not possible for everything within it to be voluntary if you are to receive credits at the end of it. However, what does voluntary mean? If we take the case of a competence meeting, one of the requirements is that every master’s student in the programme conducts such a meeting. On the other hand, the amount of effort they put into this part of the programme is voluntary. In any case, they have fulfilled the study-related requirements, and do not receive grades. The assessment is based on whether or not the competence meeting is accepted or not accepted. The description of the competence meeting is included as part of the master’s thesis course. They need to have it completed before their master’s thesis is submitted for grading. One could say it is voluntary whether one learns a great deal or almost nothing at all from conducting such a meeting. The attraction of using this method is that the student can fill these meetings with the content he/she is interested in, while the university requirements are almost exclusively on a more formal level. Another attractive aspect is that they can combine a study activity with something they need or ought to do as part of their ordinary work. They may take initiatives that would otherwise be difficult to take if it were not a study programme requirement. One such example is the interview Thorhildur G. Egilsdottir did with Professor Tom Andersen while he was attending an international conference. By itself, such a private interview would not have been regarded as a legitimate use of a key speaker’s leisure time. (See the interview in the link)

In ordinary face-to-face education on campus, a collaborative learning strategy requires students to participate in learning communities. The individual freedom for each student may create tension and appear as problematic for the entire group’s learning process. By referring to the learning process we get from a collaborative activity, we are emphasizing the needs of the group over those of the individual. In the end, participating in these groups will be rewarded with new knowledge. A collective orientation is often stressed throughout the entire process.

The off-campus student noted that competence meetings provide good possibilities for creating online communities among distance-education students. However, the meetings may need to be more organized, e.g. by creating a system of learning partners. A learning partner service is a system that helps a student to find suitable fellow students with whom he/she may build a learning community. The possibility of individual freedom is often a motive for embarking on flexibly-delivered studies.

Competence meetings take place in a network that is part of a cooperative learning community. I agree with Paulsen (2008) that cooperation with others should be attractive and appealing. In the context of social work and the importance of developing communication within social systems, I think it is preferable however to also have an obligatory component within a cooperative learning approach. Students that do not contribute to a learning community cannot be perceived as a learning resource for others.

A competence meeting is an interactive system. According to Luhmann, societies are divided into different systems, and the function of the educational system is to steer people in the direction of definite goals (Qvortrup 2005). This system divides members into teachable (resource) and risk (threat) pupils/students. Students must learn to handle knowledge and no-knowledge and understand the distinction between them (ibid). Students can be identified in two types of systems: social systems that are maintained by communication and psychic systems that are maintained by conscious processes. A system can also be defined as interaction and communication within borders. There is more communication going on within the borders of a system than crossing borders between a system and its surroundings. Each system creates its own surroundings and its own context. People, as represented by psychic systems, are parts of the context when social systems within a society are created. For that reason, students who participate in a competence meeting are both inside and outside this social system. With his identification of psychic systems, Luhmann (1993) rescues people from being totally defined by society, and they get a place where they can develop their own thoughts and feelings. Social systems develop in order to cope with external complexity. The reflective teams that Tom Andersen developed to facilitate reflections upon reflections (Andersen 1994) can also be regarded as social systems. Both Andersen (ibid) and Luhmann (1993) have as their premise that we are not able to instruct systems, that an input to a system can only “irritate” it, and that the output will be a result of interaction with the systems’ own internal logic. Tom Andersen had close contact with the US-based Galveston Institute in Texas, which published an article entitled “Problem determined systems” (Anderson, Goolishian & Winderman 1986), and the connection here towards Luhmann can also be identified. Problems are maintained in language by a problem-determined system and are subsequently dissolved through conversation (ibid).

Language can basically be conceptualized in two ways: as system and structure, or as practice and communication. It is necessary to take context into account in order to be able to understand the communicated meanings and functions of what is said by actors in specific situations (Linell 1998: 3). According to social constructivism (Berger and Luckmann 1966), reality is constructed through a dialectic process between social relations and social structures, and symbolic interpretations play a very relevant role in the social construction of reality. When practitioners are talking about what they do, they sometimes need to develop new expressions or metaphors to grasp the local and contextual interpretations, e.g. by using narratives, which have such a flexible or elastic form that enables them to contribute to the comprehension of small nuances that complement theoretical knowledge (Erstad 2005).

When we communicate, we do not know for sure if various participants have a similar interpretation of a phenomenon. We can only explore differences, misunderstandings and miscommunications (Rommetveit 2001). “Poststructuralists insist that words and texts have no fixed or intrinsic meanings, that there is no transparent or self-evident relationship between them and either ideas or things, no basic or ultimate correspondence between language and the world” (Scott 2003: 273). We will never be able to confirm what was actually meant or be able to explore the full complexities of the interpretations of the people involved. In the attached interview, Tom Andersen talks about the third reality as “the moving and invisible” one. Here, people communicate through metaphors. In Luhmann’s (1993, 2002) system of theoretical perspective, he tells us that subjects cannot communicate with each other, and only communication can communicate. We can interpret this to mean, for example, communication through metaphors.

A competence meeting is a concrete arena where different participants meet to present, reflect on and discuss issues relevant to an academic institution and the workplace. Theory is the most dominant aspect at universities, while a focus on practice is more characteristic of the workplace. As blended learning, competence meetings include both digital and traditional classroom-based learning activities for mediating dialogues between theory and practice. A competence meeting is a social system that functions to create knowledge (resource) and avoid the risk (threat) that it is felt as you are wasting your time. It has its boundaries regarding the limitation of time and the need for face-to-face meetings (virtual or in the same location). The leader of the meeting is responsible for the preparation phase, the introduction, to lead the discussion and to document the meeting in writing. The last part must occur if the student is going to receive credit within the educational system.

What is it to create knowledge? The challenge is to look for ways to facilitate reflections upon reflections. One needs to create a connection towards others in the discussion. The focus should be on what is said – what is there – and not on what you think was said. When engaging in dialogical communication, a person will find resonance with others, although not look for agreement or disagreement with others.

What is the risk? In this context, a monologue that does not connect with other participants’ experiences is not regarded as knowledge. This is because somebody imposes ready-made interpretations about right and wrong answers, and dialogue is not triggered. If someone is not touched or moved in one way or another in a competence meeting context, we can then frame it as not-knowledge.

Where does this bring us? In the conclusion, I will highlight three aspects for the implementation of competence meetings which will be of value for further exploration.

A culture of sharing develops when you use an internet-supported means for lecturing, discussing and holding competence meetings, etc., and you have less control over the audience. In this new ICT area, it is much more difficult to privatize what is occurring. This may create ethical considerations in relation to exploring a new and challenging theme on the internet in terms of not knowing who is in the audience. Although this is a closed net within the master’s study programme, one will never gain control over who may observe the meetings on the internet together with the enrolled students. If an interesting competence meeting is conducted, a student can even invite friends and colleagues to look at the videotaped meeting once again. Students who do not participate in a competence meeting in real time can participate in an inner conversation with what they see and hear. In this way, they will gain knowledge through a flexibly-delivered study. However, students need to listen carefully and take the time to get in touch with an inner conversation that connects their own everyday knowledge and practice to an already produced competence meeting. In the reflexive process, students must change from just being spectators to becoming participants who involve themselves in dialogues. To be a partner in a learning community, the student also needs to embark on external conversations with partner students.

How can we strengthen an active learner-centred pedagogy by appraising public exposure and a sharing culture in the production of knowledge?

Exploring practices and processes in social work can challenge the contemporary focus on results and evidence. In social work, there is a debate regarding evidence-based practice, which focuses on more general guidelines, and looks for the effects produced in social work (Eskelinen, Olesen & Caswell 2008). A more social constructivist approach with an interpretive and linguistic turn will focus on developing practice from within through critical reflection (ibid). Discussions and deliberations can be documented in a competence meeting as a way of safeguarding practices. Such a documentation process can open up new ideas in how to cope with difficult life situations and create empowering experiences for the participants. Reflective processes can provide a critical stance towards unified descriptions by also emphasizing oppositions and contradictions.

A feeling of community is an important component of participation in a competence meeting. It is a challenge to create a learning activity so that both on-campus and distance-education students get the feeling of belonging to a community. Face-to-face interaction is of great value to the students. Off- campus students have reported that it feels as if they are actually on campus when the communication is happening in real time. Since the main challenge for many students is that they cannot travel to the campus for various reasons, a competence meeting will need to use a video-conferencing system. The pedagogical challenge is to provide academic content, examples and situations that demonstrate how combining the aims of both freedom and social unity can yield optimal individual freedom within online learning communities. Flexible studies, meaning both on- and off-campus studies, should emphasize developing different reflective, practical methods that create a dialogue among participants, thus reducing the monologue approach to education.

Andersen, T. (1994). Reflekterende processer. Samtaler og samtaler om samtalerne. Dansk psykologisk Forlag. København.

Anderson, H., Goolishian, H., & Winderman, L. (1986). Problem determined systems: Towards transformation in family systems. Journal of Strategic and Systemic Therapies, 5, 1-14.

Anderson, H., & Jensen, P. (2007). (eds.): Innovations in the Reflecting Process. Karnac Books.

Bakhtin, M. (1986). The Problem of Speech Genres. In M. Bakhtin. Speech genres and other late essays. Austin Texas USA: University of Texas Press Slavic series.

Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an Ecology of Mind. Ballantine Books. New York.

Berger, P.L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The Social Construction of Reality. Penguin Books. New York.

Bjørke, G. (1996). Problembasert læring - Ein praksisnær studiemodell. Tano Aschehoug.

Bozalek, V. (2007). ETHICS@http://www.kewl.uwc.ac.za: The potential of e-learning for the social curriculum.In The Social Work Practitioner-Researcher, Vol. 19 (3)., 2007.

Erstad, I.H. (2005). Erfaringskunnskap og fortellinger i barnevernet. Dr. Polit. Avhandling, Universitetet i Tromsø.

Eskelinen, L., Olesen, S.P., & Caswell, D. (2008). Potentialer i socialt arbejde Et konstruktivt blik på faglig praksis, Hans Reitzels Forlag, København.

Fook, J. (2002). Social Work: Critical Theory and Practice. SAGE publications.

Innjord, A.K. (2006). Ubehaget. Del av den profesjonelle selvforståelsen? In A. Røysum (ed.) Sosialt arbeid Refleksjoner om kunnskap og praksis FO, Oslo.

Linnell, P. (1998). Approaching Dialogue: Talk, interaction and contexts in dialogical perspectives. John Benjamins Publishing Company. Amsterdam/Philadelphia.

Littlejohn, A., & Pegler, C. (2007). Preparing for Blended E-Learning. London and New York., Routledge.

Luhmann, N. (1993). Sociale systemer. Grundrids til en almen teori. Translated by John Cederstroem and Jens Rasmussen, Munksgaard.

Luhmann, N. (2002). Theories of Distinction. Stanford University Press, Stanford, California.

Michaelsen, H.C. Tom Andersen til minne (1936-2007) In Norsk forening for familie terapi. http:www.nfft.no/news.aspx?id=1167. Uploaded 21.05.2009.

Olsen, R., & Oltedal, S. 2007. (eds.) Blikk på praksis. Sosialarbeidere forteller fra yrkeslivet. Cappelen Akademiske Forlag.

Oltedal, S. (2006). Fleksibelt tilrettelagt masterstudium: Irrelevant å skilje mellom nær og fjernstudent? In Fra erfaring til kunnskap Noen lærdommer fra utviklingsprosjekter 2005, Norgesuniversitetets skriftserie, Tromsø, 2/2006.

Paulsen, M.F. (2007). Kooperative frihet som ledestjerne i nettbasert utdanning NKI Forlaget.

Paulsen, M.F. (2008). Cooperative Online Education. In Seminar.net Media, technology & lifelong learning. Vol.4, Issue 2, 2008.

Pithouse, A., Lindsell, S. & Cheung,M. (eds) (1998). Family Support and Family Centre Services: Issues, Research and Evaluation in the UK, USA and Hong Kong. Aldershot: Asgate.

Qvortrup, L. (2005). Society`s Educational System. In Seminar.net Media, technology & lifelong learning. Vol.1, Issue 1, 2005.

Rommetveit, R. (2001). (interview) In E. Maagerø and E.S. Tønnesen: Samtalar om tekst, språk og kultur. Landslaget for norskundervisning. Oslo: Cappelen Akademiske forlag.

Rønning, W.M., & Grepperud, G. (2006). The Everyday Use of ICT in Norwegian Flexible Education. In Seminar.net Media, technology & lifelong learning. Vol.2, Issue 1, 2006.

Sagatun, S. (2008). Kjønn i sosialt arbeid med ungdommer og foreldre. Universitetsforlaget, Oslo.

Schutz, A.. (2005). Hverdagslivets sociologi. Hans Reitzels Forlag (English edition 1972).

Scott, J.W. (2003). "Deconstructing Equality-Versus-Difference: Or, the Uses of Poststructuralist Theory for Feminism." In C.R. McCann, & K. Seung-Kyung(eds.) Feminst Theory Reader, Routledge, New York and London.