Developing professional competence by internet-based reflection

Marianne Aars

Associate professor, Physiotherapist, cand. polit

Tromsø University College, 9293 Tromsø, Norway

Email: marianne.aars @ hitos.no

Abstract

This article aims at giving an example of how practical, clinical knowledge can be explored by the use of a tailor-made Information and Communication Technology (ICT)-tool: Physio-Net. In constructing content to this particular internet- based resource used for bachelor students at Tromsø University College, a clinician expert physiotherapist contributed with a detailed analysis of her own practice and its underpinning rationale, displayed by film and text simultaneously. The clinician was interviewed about how the work had affected later practice and why, and her experiences are discussed in terms of reflective practice. Internalised ways of thinking and acting were changed; she became more aware of the importance of taking the patient’s perspective, of the interaction in the situation, and made more careful conclusions in the clinical reasoning process. Time, observation, writing and guidance were important clues to this learning process and outcome. It is concluded that looking into one’s own practice amongst “critical friends”, mediated in a transparent mode as the Internet tool provides, constitutes a valuable learning potential for the individual and might contribute towards making professional practice more open and easier to discuss and develop.

Introduction

As health care professionals physiotherapists need to update and develop their knowledge to be able to perform “best possible practice” for the benefit of their patients. Today there is an increasing demand for research to document the effects of physiotherapy in the medical, scientific tradition with clinical controlled trials (Ekeli, 2002; Thornquist, 2003). While this is much needed, we also have to investigate clinical practice– as it is practised – and its underpinning rationale. How can we make the practical professional knowledge of physiotherapists accessible? And how can we make it the object of scientific investigation? These are important questions to raise for the development of physiotherapy as a profession. In her book: "Generation of knowledge in physiotherapy” from 1988, Eline Thornquist says:

”One prerequisite for preserving and imparting the undisclosed knowledge of a professional field - the legacy of knowledge based on practical experience - is first and foremost to acknowledge its central role, and secondly to define its terms and systematize it as far as possible” (p. 24) (Thornquist, 1988).

This entails the physiotherapist's exposition, substantiation and investigation of his or her practice, and the necessity to make practical experience and clinical knowledge accessible in all dimensions.

In this article, I will discuss the results from a study, conducted in collaboration with an experienced clinician, which took place in connection to producing content to a tailor-made internet resource, for a particular bachelor program in physiotherapy at Tromsø University College. In constructing this internet resource, Physio-net , one of the important aims was to conceptualize practical experience-based knowledge for the students to learn from in various ways. The experienced clinician, “Bente” documented her knowledge in assessing a particular patient with shoulder problems. She video-recorded the assessment, and described, analyzed and underpinned the rationale for her actions in a specific manner. The video, with accompanying text, became a product; a guided analysis, within “Physio-net”. Bente found the work interesting and satisfying. She also found that it contributed to changing ways of thinking and acting in later clinical situations, particularly in relation to the conceptualising and interpretation of the lived experiences and symptoms of the patients. I found this so interesting that I investigated her learning experiences further in an interview. The research question I address is: How does an internet-based reflective analysis of one’s clinical practice stimulate professional development and what is required? By using Bente’s experiences as empirical data and discussing them in theoretical perspectives concerning the development of reflective clinicians and lifelong learning, I want to make a contribution to how one can develop professional competence from within practice itself.

Background: Development of an Internet- based Resource in a Decentralized Curriculum

At Tromsø University College we developed a decentralized, part-time Bachelor program in physiotherapy in 2003 . The program was established as a response to the University College's desire to offer flexible courses of study that were suitable for students with family obligations or who for other reasons wanted to extend the period of time for completion of their studies. The curriculum outlines a study programme lasting four years, instead of three, and combining plenary seminars on campus, periods of practice and intermediate periods of independent study. The independent study intervals include self-study and group work, as well as skills training with a physiotherapist in the practical field. The database Physio-net was developed as a reference support for the students' learning process. It was made in close cooperation with Britt Kroepelien, professor in Art History . Many internet-based learning supports today deal with the exchange of information and communication and operate as Learning Management Systems (LMS), rather than with the content of a program such as Content Management Systems (CMS) (Garrison et al., 2003). When we constructed Physio-net we particularly wanted to emphasise the content aspects, and especially focused on documenting practical, clinical knowledge in the profession. This was due to the medium’s potential for doing this by using different modes such as film and text simultaneously, and because theoretical knowledge is far more accessible in books and articles. The content of Physio-net today consists of lectures, photos, concepts, videos with or without expert comments, and students’ own work as analysed videos. It serves both as a repository of knowledge where students can search through the database with help of keywords, and as a portfolio for learning assignments. It is used for working with specific tasks as well as an independent source, from which to get inspiration and information.

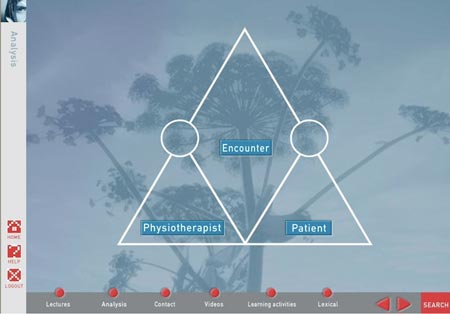

The basis for how physiotherapy is presented throughout Physio-net rests on an understanding of physiotherapy as a mutual interaction between the physiotherapist and the patient within a given context (Engelsrud, 1992). This is illustrated on the web site by means of the following displays:

Ill. 1: Displayed images on some introduction sites in Physio-net

Through these illustrations, it is acknowledged that both the physiotherapist and the patient bring with them a form of competence to the encounter: the physiotherapist with professional specific skills and knowledge and personal knowledge, and the patient with lived experiences, goals/intentions and expectations for treatment. The encounter between the physiotherapist and the patient is influenced by their composite experience respectively, and by what is created in the encounter between them, there and then (Thornquist, 1998).

In the part of Physio-net which is called Guided Analyses, which was used in this particular study, real-life situations are presented in which the physiotherapist examines and/or treats specific patients. Through video clips and texts, the situations are analysed step by step.

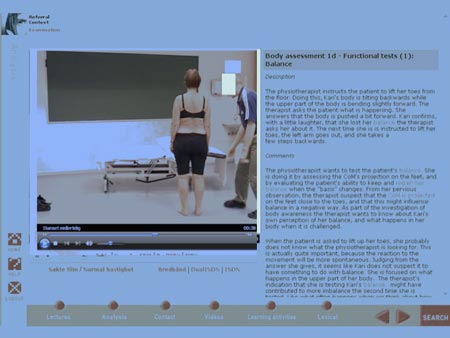

Ill 2. From another guided analysis, showing some of the commentary regarding examination of balance

Each film is divided into 40-50 sequences. First there is a brief description of the situation. Following this there is a commentary that incorporates the three-dimensional perspective: "Physiotherapist", "Patient" and the "Encounter". By making a guided analysis you define important knowledge based on practical experience, knowledge that would otherwise remain more or less undisclosed. In short you are engaged in reflecting upon what you are doing, which leads up to the theoretical perspectives applied.

Theoretical perspective: The "reflective clinician"

The idea that reflection contributes to better practice can be traced back to philosophers such as Dewey and Schön. Both emphasize the significance that reflection in – and reflection on- practice has for the acquisition of knowledge and the development of the expert clinician (Dewey, 1933, 1938; Schön, 1995). An expert automatically reflects on his or her own practice and regards development of knowledge as a lifelong learning process (Kolb, 1984). He or she is in continual professional development (Eraut, 1994) and has an independent motivation that propels the process.

Within the field of physiotherapy, reflection is seen as an imported and integrated aspect of developing competence in different arenas. Jensen et al. (2000) has contributed with research regarding the development of clinicians from novice to expert, while Hayward (2000) has done similar research on the development of physiotherapists as clinical supervisors, and Clouder (2000; Clouder et al., 2004)on the development of physiotherapists as teachers. During recent years the term "clinical reasoning" has been applied to illustrate and explore how health care workers reason in clinical situations (Higgs et al., 2000; Higgs et al., 2004). The ways in which researchers use the terms "reflection" and "reasoning" show that they may be understood as overlapping but not concurrent terms. Both reflection and reasoning entail that thinking and acting are connected, and that the clinician engages in ongoing processes of evaluating and acting within a given situation. Clinical reasoning, however, has a somewhat more restricted meaning and focus than does reflection. The purpose of clinical reasoning is to promote expedient problem-solving and effective decision-making processes based on proper and extensive "data gathering" on the patient, and focuses on cognitive dimensions. Reflection, on the other hand, opens for a greater degree of critical focus on various aspects of treatment, in addition to those associated with general reasoning about a patient's problem. Focus is directed to a greater extent on the experiences that are the basis for thinking and reflection, and makes the therapist’s feelings in a situation, and ethical issues, for instance, relevant. In order to critically reflect upon one's own practice, it must be described and made explicit, but must also meet resistance of some kind. While reflecting, there is a risk of merely justifying what you do or did (Thornquist, 2003), and therefore it is necessary to challenge the clinicians’ reflections and/or make clinicians’ practice the object of theoretical analysis. Only then can one speak of reflection as a contribution to professional development in the true sense of the term.

Data and methods

The involvement in producing content for Physio-net, and the investigation of how that involvement affected the clinician’s clinical work, can be seen as different phases in the research project and are presented in the following account. The research strategy is described in terms of action learning and action research.

Collaboration in producing content for Physio-net

When we started our new study program we held a seminar for all 14 partners and clinical supervisors who were connected to the new program, to inform them of the differences between the programs and their role in stimulating the students’ learning in the decentralised curriculum. Everyone was invited to contribute professional material for the production of the Physio-net web site. Because of the workload involved, only one felt she had time and opportunity; Bente. She agreed to produce a guided analysis on one of her own patients. She had more than twenty years of experience from private clinics and had cooperated closely with surgeons and physiotherapists in a hospital with extensive competence in shoulder rehabilitation. She seemed to be an experienced physiotherapist who had developed special competence with shoulder patients.

The parameters for Bente's work were that she was to describe, analyse and evaluate what she saw and heard in the assessment of one of her own shoulder patients. This should be done in a manner that took into account the tripartite perspective: Physiotherapist, Patient, Encounter, and in consultation with me. We had two lengthy meetings during which we watched and discussed the film and the structure for the written presentation. During the course of the project, she sent draft texts to me on eight occasions, received comments in return, and we subsequently discussed her work over the telephone Especially in the early and finishing phases of the analysing of the film, she wanted – and got-feedback. She spent 130 hours working on the analysis over a period of five months and produced the Guided Analysis “Bente, 39 years”. The analysis consists of 50 min. of film, made into 44 sequences, where 10 regard patient history, 32 functional assessments and tests and 2 regard the conclusion. Each of the film sequences are accompanied by a detailed written analysis of what is going on, and the underpinning rationale from the tripartite perspective.

The research project

When our collaboration was over, I met Bente for a one-hour informal conversation. On her own initiative she told me how instructive the work had been and how it had contributed to changing her own practice. This inspired me to investigate her experiences further. She agreed to be interviewed and gave her written consent. The interview was held two weeks later by telephone and lasted 50 minutes. The interview focused on Bente's motivation for agreeing to the work, what she had gained from it, and what had contributed to any changes in practice. I took notes from the interview during our conversation and made a report of four pages, summing up the essence. This was sent to Bente immediately, for reviewing and comment. She responded shortly afterwards supporting the content of my report, and gave two pages of supplementary comments and reflections to elaborate on the learning outcome of her work. She was invited to join as a co-author of the article, but felt the workload and commitment was too much at the time. An earlier draft of this article was sent her for review and comments, which she responded to with interest and support. She felt the article expanded her experiences in an interesting and non-conflicting way.

Research strategy: Action Learning and action research

While working with the guided analysis Bente reflected upon her previous assessment with one patient in a certain way. From the results the reader will learn that this stimulated a learning process which had consequences for her practice with later patients. She was engaged in a process in collaboration with me, which has similarities to that of an action learning process, that is: “a continuous process of learning and reflection that happens with the support of a group or ‘set’ of colleagues, working with real problems with the aim of getting things done” (McGill et al., 2001) . Our collaboration could also be classified as action research in terms of this definition: “it is a collaborative, critical and self-critical inquiry by practitioners into a major problem or issue or concern in their own practice” (p.3) (Zuber-Skerritt, 1996). The concepts action learning and action research seem to overlap, and what separates them can be disputed . From the literature it seems that action research focuses more clearly on the researcher having a responsibility for documenting and analysing the process in a systematic way and bringing in theory to open up for new understanding (Reason et al., 2001; Tiller, 1999), and that the role of the researcher is to be a critical friend (Aagaard Nielsen et al., 2006). In action learning there is less emphasis on the documentation process and the roles of the actors involved are less defined. Even though the premises for the collaboration between Bente and me were not her professional development, or research, the process and the results have similarities to that of action learning and research. Bente gained new insight into her practice while working with the guided analysis, and she adjusted her conceptions and treatment in her encounters with other patients. My role was to support and guide Bente’s analytical work and introduce her to the tripartite structure in Physio-net. This might not qualify as being a critical friend in the strong sense of the word, but nevertheless the structure especially, which is shown in the results that follow, contributed strongly to Bente's focusing on specific and new dimensions in the assessment situations and to her learning process. Preferably, if living up to a full action research approach, Bente should have been involved in analysing her own learning, but she didn’t have the time to involve herself more than she did. Therefore the final stages of the project were done by me, analysing Bente's experiences in the light of the theoretical perspectives applied. I have chosen to present the results and the discussion of them in separate sections in order to provide the clinician with a clear voice. During the analytical process in presenting the results I looked for what Bente learned professionally and why, and chose categories to distinguish important learning outcomes. For the discussion I interpreted the findings and analysed the material in order to illuminate key issues in what it takes to learn from reflection upon practice. Hopefully this will contribute to a deeper understanding of some important aspects of reflection and how the transparency in new technology can stimulate the processes of reflection.

Results

What has Bente learned and why? To answer these questions I have chosen to quote rather long excerpts of text . The chosen categories capture four dimensions of professional development; regarding patient, interaction, interpretation and the connection to personal development, and one category which addresses the project’s significance in the learning process. My comments are brief and made close to the text itself.

The patient emerges more clearly

What Bente stresses as the most important lesson learnt from describing and justifying her own practice is associated with the manner in which she views the patient.

”I think, looking back, that maybe the most important thing I got out of this is seeing and listening to the patient. Who is she? What kind of life has she led - what kind of life is she living now and what are her hopes, dreams and desires for her life in the future? These are elements of significant importance for treatment and the outcome of treatment. It is easy to miss the overall picture during a busy workday. For example, in terms of P's comment that playing the piano is impossible/difficult, I might have hastily thought "abduction is problematical". But when I take the time to "absorb it", it is a paradox that even a moderate activity such as playing the piano is difficult - and here we are talking about a girl who has had a high degree of self-realization and a great need to be active and functional. It feels necessary to make priorities and put out a lot of effort - including interdisciplinary - for patients like her. What are her expectations of life; what is required in order to meet her expectations? What is the most urgent in order to get started? How much of an effort shall we make? Some patients I have to slow down a little. Others I can challenge: in order to reach this or that goal: what are you willing to contribute yourself? How will you do this? I challenge patients more directly than before.”

Her work with the film of one consultation of a patient has resulted in Bente's seeing patients' lives with deeper insight. She ascribes importance to such insight in her professional choices, and she feels that she has acquired perspectives that can make physiotherapy more meaningful both for herself and for the patients. In the prioritizing of patients as well as for the use of resources, she seems to have added some new dimensions where the patient’s expectations and own efforts are taken more into account.

Interaction seems more important

Bente has become more conscious of the interaction between herself and the patients.

”I have done a good deal of thinking about - and critical appraisal of - my own role. For example: How did it affect me that P was so unwilling to open up, that she was despondent and tended to be curt when answering questions? I can still feel my desire to push her to get started and open up - Was I trying to make it easier for myself?! Especially in the physical part of the examination, I think that I have become more conscious of the interaction. The placement of my hands, eye contact, physical contacts, and not least of all observation of the patient beyond what the test in question can provide in terms of information.”. I have become more aware of breathing, of body language. I have noticed these things before, but they haven't been seen as important aspects until now.

Here Bente illustrates that the encounter with the patient entails experiences of both an emotional and physical nature. She has become more aware of the relational dimension of the physiotherapist, and of the importance that both the patients’ and her own behaviour and manner of treatment have for what is generated in the situation. The experiences with doing the analysis have obviously been significant for reflection upon her own practice, and for the changes she has made.

Interpretations are made more carefully

Bente is interested in conducting examinations that contribute to identifying the structures involved in the presentation of the patient’s problem. But she interprets her findings more critically.

When I examine patients, I still do many of the same things as I did before. I haven't really changed that. But I have changed the explanatory models a little, and I am more critical of them. I have discovered that I sometimes make hasty decisions, or I interpret too quickly based on what I examine in the given situation. Can I be certain that things are as I see them? I see what I see, but the reason why things are as they are is not necessarily as self-evident as it might seem. I am now more humble in relation to what I think I know. My explanatory models are more open. I am more curious and investigative.

Bente has held on to her usual examination routines. She masters them well and thinks they give her important information, but the information is evaluated more critically. She has opened up for an understanding of physical complaints that makes her even more aware of complexities and circumstances involved in every clinical problem.

Professional and personal development

A motivation to develop herself is one trait that characterizes Bente. She thinks that contact with students contributes to professional development.

The motivation was that I wanted to get involved with this kind of work in order to develop myself professionally - for my own sake. It was only later that my motivation also included using this for students. When I started work on the video, I thought of it as a gift. Being able to watch oneself. I thought: What a tool! And then I began to think that it was a gift for students as well. ”To dare to make a professional contribution is part of one's own development. I have become more sure of myself, but at the same time more humble. I have presented my way of thinking. When I talk about "my way", do I place more value on it, perhaps? At the same time, I am open to the idea that there are other ways of doing things." I often think about the film/project. In that way, there was a kind of platform constructed, from which to continue to develop. There is a continual re-working and maturation process. I try to translate some of this into practice - in order to see what happens next..."

Bente was motivated to being observed by others for the sake of her own professional development. She experienced that observing herself on film, over and over again, made her even more aware of herself. It may appear that she has developed greater self-confidence? by working with the underpinning rationale for her work, and at the same time she has become more humble. This has affected her professionally as well as personally.

The significance of making a guided analysis for professional development

Through the textual excerpts above, Bente emerges as a more inquisitive and self-critical physiotherapist than she felt she had been previously. She is now more conscious of the influence that relationships with patients have in the treatment situation, and she has changed in part her way of thinking and acting in terms of her own practice. What has contributed to this change?

First and foremost, it is having spent so much time looking at one's own practice - and writing about it. When a person simply observes and says nothing about what one observes, one will be less critical than when one writes down what is observed. What was it that I observed? It requires one to be more accurate, to take into account what one observes and what one's observations are based upon. It has become important to set aside whole days at a time for this. The best days have been when I spent as many as 8-9 hours. And then structure was important. Very informative. I hadn't thought so before. If I didn't have to think about this structure, I would not have learned as much. It made me visualize the person and the physiotherapist's place in this person's life. ”Part of me protested against this. Eventually it became more and more interesting. It was a question of clarifying something that one never says anything about."

Here we see first and foremost that setting aside time for observation and self-evaluation was of great importance. The use of video in this process was very valuable. In addition, the documentation process in itself was an extremely powerful instrument of learning. The innovative aspect in this particular project seems to be due to the fact that observation and documentation are combined in new ways, and that the medium and structure in Physio-net challenged Bente to use the three-dimensional perspective in a clinical situation. Although she seems to have found this perspective rather strange in the beginning, she had sufficient "staying power" to use it throughout. In the end she found that the structure actually contributed especially to focusing on dimensions of physiotherapy which easily slip the attention, like the information patients give without uttering words, and related to the quality of the interaction between herself and the patient.

Discussion

Bente's account is an example showing that thorough reflection about one’s own practice, from an isolated patient situation, can function as a motivator for change in practice. Reflection is thus one important aspect of professional development. Many will perhaps contend that these changes were not radical, but I consider them nonetheless to be important. It would appear that Bente has gained an insight that permits her to assess a patient's problems and her own role in the treatment process in new ways. She seems to meet patients with increased inquisitiveness and with a renewed sense of security. This may in turn be interpreted as Bente having acquired tools that promote reflection within - and upon - her practice, which characterises processes denoted as "lifelong learning” (Kolb, 1984) and ”continual professional development” (Eraut, 1994). In such processes, it is a question not only of making changes, but also of corroborating what already functions well. In the following I highlight important issues in developing professional competence through reflection. Firstly I address general issues regarding the significance of different kinds of questions, and then I discuss some aspects of what it takes to learn from reflection.

Reflection in general

An important dimension in professional development is the ability to constantly question oneself. Certain types of questions may be more suitable than others to promote reflection (Dewey, 1938; Eraut, 1994). Bente posed both "what” and “how" questions of the type: What am I actually observing? How do I understand what I see? And "why" questions: Why did I act in that manner? It is the “what” and “how” questions that contribute to reflection about the assumptions that underlie one’s own ideas and actions, and that provide the basis in particular for considering alternative ways of thinking and acting (Eraut, 1994). The "why" question will open to a greater extent for justification of one's own practice, which again can reduce the risk of adjusting and changing current practice (Eraut, 1994; Thornquist, 2003). In physiotherapy we need all types of questions. It is necessary to investigate, document and further develop one's clinical knowledge based on experience using "what" and "how" queries so that it will be less "tacit" and open to change and adjustment (Thornquist, 1988, 2003). It is also important to justify one's practice based on "why" and to remain open to the possibility that justifications need to be renewed.

Learning: A relationship between routines and reflection

Research shows that a skilled clinician is characterized by the fact that certain actions appear automatic and can be performed intuitively (Dreyfus et al., 1999; Jensen, Gwyer, Shepard, & Hack, 2000; Jensen et al., 1990). It is a qualitative criterion that many ways of thinking and acting are internalized and comprise a form of confidence. What is the relationship between routines and reflection? What is the relationship between the knowledge that is worth preserving and that which is perhaps ready for change? I will elaborate on this in the following.

Bente has subjected many aspects of her own practice to scrutiny; some aspects have been preserved, others have been changed. The examination routines she uses for patients with shoulder problems comprise some of the knowledge she continues to apply. Her clinical reasoning associated with what she observes, hears and does, however, has been changed: she has opened for a wider and more careful interpretation of her own findings, and she takes more seriously the patient's life situation and allows it to have a greater bearing on her choice of action and treatment measures.

Through examining her own practice again and again and in a different light, Bente was able both to observe her experiences in the given situation, and to gain new experiences of a cognitive, emotional and bodily character. She has reflected over much of what she normally takes for granted, or the "tacit” dimension in her knowledge based on experience (Polanyi, 1983). It is most likely that outside observers would have noticed other dimensions in Bente’s practice, worthwhile investigating. From the perspective of learning as an individual, lifelong process of construction, however, it is pointed out that what is learned has its origins in the experiences of the learner (Kolb, 1984). Continual professional development is not necessarily stimulated if more and more is treated as problematic, while less and less is taken for granted (Eraut, 1994). Eraut points out that the process of reflection and self-adjustment takes time and may be experienced as tiring. The process entails both re-learning and risk-taking. If absolutely everything concerning one's own practice is questioned, this may quickly lead to an overdose (Eraut, 1994). Skilled clinicians therefore, develop through a balance between consolidation of routine tasks, increased readiness to act and reflection about what one normally takes for granted.

Learning through demanding and structured reflection

Bente's learning process shows how important it is with structural conditions that contribute to stimulating learning processes in practice. The most important ones in this case are linked with the disposition of time, use of video, writing and structure in the Physio-net web site. Time in itself is important both for gaining access to - and for enabling a certain distance from - the object under investigation. Use of the video makes possible the recall of sensory impressions, feelings and thoughts that were present in the situation, as well as opening for new ones. Video, in other words, is a highly suitable medium for developing an analytical perspective, and as a source for new experiences (Engebretsen, 2006). Writing, in turn, is suitable not only for putting one's experiences into words, but to experience anew and to think further (Bolton, 2005). The alternation between observation - text writing - and reflection appears to have been fruitful in Bente's learning process.

The basis for reflection lies in the linguistic, i.e. language has a constitutive role in consciousness (Hammarén, 2005). Writing and processing a text are particularly important tools for in-depth reflection, she says, because as you develop your capability to be in dialogue with language, the reflection will be developed further (Hammarén, 2005). Bente is of the opinion that writing made her more critical and reflective, and it is reasonable to assume that the processing of language in itself contributed to her perception of professional development. Moreover, it appears significant that writing was structured in the tripartite perspective: the Physiotherapist, the Patient and the Encounter. All action research stresses the important fact that learning must be stimulated by the introduction of theory and definitions, which is the responsibility of the researcher(s) (Reason & Bradbury, 2001; Tiller, 2004; Aagaard Nielsen & Svensson, 2006). In learning from the participants’ experiences it is necessary to analyse them in theoretical perspectives that will add to the meaning and the understanding of them. The experiences need to be challenged and elaborated. The categories "physiotherapist", "patient" and "encounter" are very general terms closely associated with practice, but which all the same proved to be challenging enough for Bente to discover new aspects of herself and her practice. What was easiest to put into words was associated with the "physiotherapist", and to those elements of her professional activity that fall under the category of "clinical reasoning". The increased focus on the patient - and the perspective of interaction - were more unfamiliar, but were also the elements, triggered by experiences of initial resistance which she reflected upon, that opened for new discoveries and changes of practice.

Learning as a risky undertaking

In order to develop oneself as a professional practitioner, it is a question of both reflecting over oneself and subsequently making those reflections accessible for others. Displaying one's practice through video recordings and texts is a risky undertaking that requires boldness. Bente addresses this issue. She was very aware of the fact that what she was doing entailed taking a stand for her professionalism - both in terms of herself and others. She put her professional integrity at stake. In itself this can promote both professional and personal development (Hammarén, 2005).

The process of developing oneself as a professional practitioner illustrates, first of all, the dynamics and the strength that is inherent in the relationship between being made visible to others and to oneself. The other aspect that emerges is the importance of encountering professional challenge in an atmosphere of recognition and respect. In action research traditions such a dimension is stressed in the research process and for the relationship between the "researcher" and the "practitioner" (Reason & Bradbury, 2001; Aagaard Nielsen & Svensson, 2006). I maintain that my relationship to Bente expressed recognition for her work, while the structure in Physio-net, as well as my guidance of it, offered her some challenge. In order to grow out of the experience of being exposed to the critical scrutiny of others, it appears to be entirely necessary to be "reasonably challenged" and to be received in an appreciative manner (Eraut, 1994; Reason & Bradbury, 2001).

Conclusion

In this article I have discussed findings from a project investigating the effects of a clinician reflecting upon her practice by means of an Internet-mediated tool, in collaboration with myself as an educator/researcher. Since the findings are based on one case only, they are tentative, but can still point to important attributes of professional development. To display and investigate experience-based practical knowledge on Internet may appear to be a contradiction in terms. The project described here has demonstrated that it is possible. An Information and Communication Technology-medium like Physio-net, with its visual properties, is particularly well suited to highlight and illustrate experiential knowledge, so that it emerges in new ways. The work in describing one's knowledge and the underpinning rationale for one’s actions seems to have great potential for stimulating professional development.

Bente's story is an illustration of the importance of standing face to face with one's own practice and revealing it to others, as well as the power for professional development that is inherent in doing so. The internet medium which combines the use of film, production of texts and suggestions for reflection represents one possible path to individual professional development for the clinician. The strategy of action learning and action research invites researchers and clinicians to constructive collaboration whereby the researcher acts as a "critical friend", rather than one who "knows best". The processes of change that occur in the individual take place in a climate that is characterized by concurrent recognition and criticism. The question remains to be answered as to whether individual learning processes also can contribute to the development of physiotherapy as a profession and a discipline, and what does it take? Is the profession served by developing individual clinicians to become more reflective clinicians? Is there enough critical investigation? These are important questions that cannot be answered simplistically, but that must be discussed. Future research needs to focus on how the forming of constructive communities to explore one’s practice in a transparent mode may stimulate reflection and promote “best practice” – both from a professional perspective and from the patient’s perspective. In my view it is important to develop a culture for reflection and professional discussion based on actual practice. To do this, obviously, requires good structural conditions, but the opportunities are evident both for investigation and critical exploration of one's own practice and for creation of constructive communities of clinicians, as well as fostering a partnership between clinicians and researchers by the use of for instance ICT-media. While this may appear easy, it is at the same time a challenging way to go. It entails exposing our practices and beginning the discussions there. Do we dare?

Acknowledgements

Heartfelt thanks to physiotherapist Bente for a good, instructive cooperative effort and to doctoral fellowship holder Britt-Vigdis Ekeli for constructive suggestions in the preparation of this article.

References

Bolton, G. (2005). Reflective practice : writing and professional development (2nd ed.). London: Sage publ.

Clouder, L. (2000). Reflective Practice in Physiotherapy Education: a critical conversation. Studies in Higher Education, 25, 211-223.

Clouder, L., & Sellars, J. (2004). Reflective practice and clinical supervision: an interprofessional perspective. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 46, 262-269.

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A Restatement of the relation of Reflective Thinking to the Educative Process. Chicago: DC Health and Co.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and Education. New York: Collier Books.

Dreyfus, H., & Dreyfus, S. (1999). Mesterlære og eksperters læring. I K. Nielsen & S. Kvale (Eds.), Mesterlære. Læring som sosial praksis (s. 52-69). København: Ad Notam Gyldendal.

Ekeli, B.-V. (2002). Evidensbasert praksis. Snublestein i arbeidet for bedre kvalitet i helsetjenesten? (Vol. 2): Eureka Forlag, Høgskolen i Tromsø.

Engebretsen, M. (2006). Making sense with multimedia. A text theoretical study of digital format integrating writing and video [Electronic Version]. Seminar.net-International journal of media, technology and lifelong learning, 2, 18.

Engelsrud, G. (1992). Innhold og interaksjon i fysioterapi. Fysioterapeuten, 59, 15-22.

Eraut, M. (1994). Developing professional knowledge and competence. London: Falmer Press.

Garrison, D. R., & Anderson, T. (2003). E-learning in the 21st century : a framework for research and practice. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Hammarén, M. (2005). Skriva : en metod för reflektion. Stockholm: Santérus Förlag.

Hayward, L. M. (2000). Becoming a Self-reflective teacher: A Meaningful Research Process. Journal of Physiotherapy Education, 14, 21-30.

Higgs, J., & Jones, M. (2000). Clinical reasoning in the health professions (2nd ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Higgs, J., Richardson, B., & Abrandt Dahlgren, M. (2004). Developing practice knowledge for health professionals. Edinburgh: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Jensen, G. M., Gwyer, J., Shepard, K. F., & Hack, L. M. (2000). Expert Practice in Physical Therapy. Physical therapy, 80, 28-43.

Jensen, G. M., Shepard, K. F., & Hack, L. (1990). The Novice Versus the Experienced Clinician: Insights into the Work of the Physical Therapist. Physical Therapy, 70, 314-323.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning : experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

McGill, I., & Beaty, L. (2001). Action learning : a guide for professional, management & educational development (2nd ed.). London: Kogan Page.

Polanyi, M. (1983). The tacit dimension. Glouchester, Mass.: Peter Smith.

Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (2001). Handbook of Action Research. Participative Inquiry and Practice: SAGE publications.

Sandstrak, G. (2003). Bruk av aksjonslæring i design/utvikling av bedriftstilpassede kurs over internett. Norges Teknisk-Naturvitenskapelige Universitet, Trondheim.

Schön, D. A. (1995). The reflective practitioner : how professionals think in action. Aldershot: Arena.

Thornquist, E. (1988). Fagutvikling i fysioterapi. Oslo: Gyldendal.

Thornquist, E. (1998). Klinikk, kommunikasjon, informasjon. Oslo: Ad notam Gyldendal.

Thornquist, E. (2003). Vitenskapsfilosofi og vitenskapsteori : for helsefag. [Bergen]: Fagbokforl.

Tiller, T. (1999). Aksjonslæring : forskende partnerskap i skolen. Kristiansand: Høyskoleforl.

Tiller, T. (2004). Aksjonsforskning i skole og utdanning. Kristiansand: Høyskoleforlaget.

Zuber-Skerritt, O. (1996). New directions in action research. London: Falmer Press.

Aagaard Nielsen, K., & Svensson, L. (Eds.). (2006). Action and Interactive Research. Beyond practice and theory. Maastricht: Shaker Publishing.

1. My translation

2. In Norwegian Physio-net is called Fysio-nett

3.15 students were admitted in 2003 and qualified in June 2007.

4. The part time, decentralised program in physiotherapy will take another 15 students from Nov. 2008, and then be established on a more regular basis.

5. Britt Kroepelien developed Art History as a distance course, mediated by internet, at the University of Bergen and was granted the Idunn prize for her outstanding work in 2001. She was a great inspirer and contributor to Physio-net, and sadly passed away in 2007. Referred to in: (Sandstrak, 2003), p. 35, but original text has been impossible to retrieve.

6. Bente's written account is reprinted in quotation marks; her oral account, transcribed for my text, is reproduced without quotation marks.

7. From the 1st to the 2nd edition of Higgs: Clinical Reasoning, it is precisely the significance of the patient-perspective that is more emphasized in the clinical reasoning process.