Survival of the -net-est?

Experiences with electronic test tools – reduced teacher hours?

by

Kristin Dale

Associate Professor, dr.oecon

Department of economics

University of Agder

Abstract

More feedback to students is demanded to improve educational quality. In large courses individual feedback is often very time-demanding for the teacher. If teacher hours are only marginally increased to cover increased student feedback, teachers should look for electronic tools for assistance with student feedback that will reduce teacher work hours, at least in the long run. This paper reports my experiences with electronic multiple – choice tests in mid-term feed-back to students in large courses in undergraduate studies. It reports a lot of the decisions that the teacher has to make when creating a multiple-choice test for a course such as the choice between a paper or electronic test, number and type of questions, number of answer options, scores for right and wrong answers and manual or electronic scoring. The paper also addresses the communication with students before and after the test, the need for administrative support and finally discusses the costs and benefits with respect to teacher hours. These experiences may be useful to teachers who consider using electronic test-tools.

Keywords: Multiple-choice test, teacher feedback, teacher workload, test construction

1. Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to elaborate on the benefits and challenges of using assessment capabilities of internet-based learning systems to evaluate a student’s progress in a specific subject. Particularly, the focus is on how the workload of the teacher changes when assessments shift from paper hand-ins to evaluations that use many of the automatic functions available through internet-based learning systems. This paper reports some experiences and reflections from the teacher’s perspective.

The ‘quality reform’ (Ot.prp. nr 40 2001-2002) for Norwegian higher education demands that students get more feedback about their learning progress during a course, and that programmes are targeted and efficient. These objectives are discussed in ‘Mjøs-utvalget’ (NOU 2000:14 Frihet under ansvar) and Stortingsmelding 27 (2000-2001) ‘Gjør din plikt – krev din rett’. Such ideas stem from the European political process to harmonize higher education across countries by the Lisbon Recognition Convention in 1997 and the Bologna Declaration in 1999 both emphasizing quality of higher education. For this and other reasons, institutions of higher education have typically introduced exam requirements in more courses than what was previously the case, and group or individual hand-ins have become more widespread and frequent. Thereby, many additional courses have assignments that need to be assessed prior to the final exam.

Universities and other institutions of higher education have lately introduced commercial internet-based learning systems like Blackboard, Fronter, Itslearning, Moodle etc to present and organize course material and course-interaction. These systems may also be used to evaluate students’ learning. These systems will vary with respect to the toolkit they offer, and which solutions they have chosen to implement tools so that the available functionalities vary across systems. To which extent such learning systems really supply useful tools relative to what is available through institutional internet pages and e-mail systems is debated (Sveen, 2007). Likewise, there is frustration with supplier’s lack of ability to supply the tools demanded by faculty and students. Given that an institution has chosen one system, users are locked in with the functionalities of one particular internet-based learning system and the ability of the institution’s administrative support staff to press for desired changes, a frustration that is illustrated by Ystenes (2007).

In courses with few students the teacher has many options for midterm requirements that will not create a big workload. In courses with many students, evaluating individual hand-ins may create a large (additional) workload, so teachers try various alternatives to reduce this extra work load; group hand-ins instead of individual ones, or multiple-choice tests on paper to standardise the evaluation and cut evaluation hours. However, given the availability of internet-based electronic learning systems, the use of electronic means to test and assess the test may reduce the additional teacher work-load, particularly in the long run. Below you find some experiences and reflections about the use of automatically scored multiple-choice tests to simultaneously give feedback to students and reduce teacher workload in big courses .

2. Various multiple-choice tests

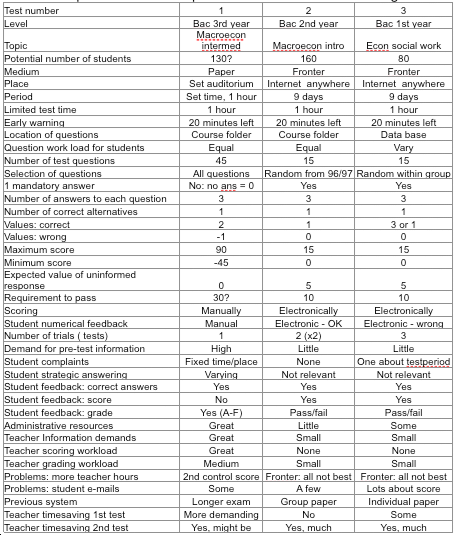

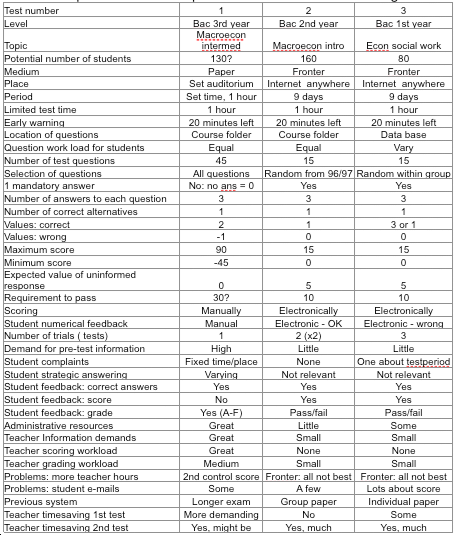

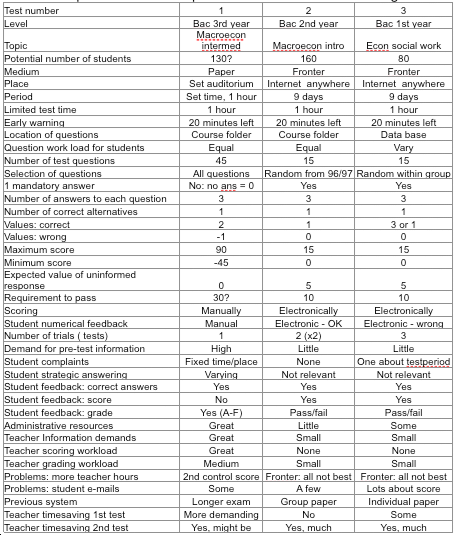

Three tests are reported in Table 1: Test 1 took place several years ago (2004), and was a multiple-choice test on paper with manual grading, and differentiated scores. Test 2 was used in an introductory course in macroeconomics in 2007, and Test 3 was used in a group of social worker students in 2007. Tests 2-3 used the electronic resources that are available at University of Agder. Detailed information about each test is shown in Table 1.

Test 1: Test on paper (reply sheet), manually scored and graded

Turning good intensions into practice, test 1 was carried trough on paper in 2004. This was a course where exams were bilingual with parallel versions in Norwegian and English. This course used an English textbook with a lot of internet-resources available. The previous year the text-book multiple-choice test had been used in the midterm-test by another colleague. This information made students work very hard to learn by heart the correct replies to the questions on internet, while they put less effort working with the textbook and exercises. Furthermore, the differences among the alternative replies were often semantic in nature, not focusing on substantial misunderstandings of a typical student. These experiences of my colleague were the reason for making a new multiple-choice test.

Generally, if you are an expert, and you don’t know, should you guess or say that you won’t answer (yet) because you are not sure? Based on such reflections I assigned 0 points to no answer, and negative points to a wrong answer. However, in such a test: offering 3 for the right alternative, 0 for no answer, and -2 for a wrong alternative, the experience showed that it took a lot of effort to score tests manually (including checking by another person). There were two ways of getting a low score: few correct answers or many answers including both many right and many wrong ones. Especially this last group of students felt very disappointed with their grades (communicated through e-mail and in my office) because they had not fully understood the strategic importance of avoiding wrong answers. Negative scores for wrong answers demand more information to be communicated before the test starts, including an explicit decision about the exclusion of the hedging option (of 2 answers) . Due to the workload of scoring a test manually when offering 3 for the right alternative, 0 for not answering, and -2 points for a wrong alternative, I shall only do this in electronically scored test in the future. Due to the strategic aspects requiring detailed student information prior to the test, I shall hesitate to use this in the future. Bar-Hillel et al. (2005) discuss how the respondent’s attitude towards risk may create a bias in answering when there is a penalty to wrong answers. They argue that the socalled ‘number-right scoring’ is superior to formula scoring with a bonus of 1 for a right and a penalty of 1/(k-1) for a wrong answer.

Test 2: Test in Fronter, in a folder in the course-room, automatically scored

To avoid hand-ins on paper (individual or by groups) in 2007 I decided to make a multiple choice test using the internet-based electronic learning system (Fronter) of my institution. In a class of 160 students I made a folder in the course room in Fronter, and made-up the test directly in this folder. Given that students would not be monitored during the test (to check whether or not they were on their own as they were supposed to be), the individual tests should look as diverse as possible (to reduce benefits from undesired cooperation). To accomplish this, 15 questions were randomly drawn from a pool of 96 questions. My intension had been to create 100 questions from the first part of the course, but in the end I ran out of ideas. Furthermore, the test should be open for response by the student only a short period needed for answering (for instance 1 hour) and not a long period sufficient to look up correct answers in the course material or to discuss with other students. In addition, the options ‘random ordering of questions’ and ‘random ordering of answers’ were chosen in the test to make two tests look even more different than they might be. Bar-Hillel et al. (2005) argue that key randomization is superior to key balancing, because it introduces no system in the correct answers that may be detected and used for strategic answering a test. Furthermore, Taylor (2005) recommends channelling effort towards the content of questions and answers.

Table 1 Experience with multiple-choice tests in various settings

To formulate short and clear questions and correct answers is demanding. However, the formulation of wrong answers is even worse to accomplish in a good way. Therefore, I decided to go for 3 answers only for every question: 1 right and 2 wrong, in line with conventional wisdom according to Taylor (2005). Amongst the 2 wrong, 1 is related to the topic, but something important should have been misunderstood (not only an issue of semantics). Upon the creation of each question and its answers, the answers had to be assigned score values. Every question had to be answered, and by one alternative answer only. The correct answer was categorized as correct straight away and assigned the value 1. Wrong alternatives were assigned the value 0.

Students could go back and forth between the questions in the test, and the test was automatically submitted when they closed it. If the test was still open at the 1 hour limit, it was automatically submitted by the system. Some students did not understand that when they opened the test just to take a glance at the set up and questions, that opening counted as one delivery even though they had not answered any question (and consequently the student got zero points). When closing the test, the student received the total score and further got to see which were the right and wrong answers. This is good for quality feedback to the students, but not ideal from the aspect of reuse of the questions in future tests.

Since the expected outcome of a complete random draw by an ignorant person is 5 points, and the maximum points are 15, I chose to make 10 points the pass limit for the test. Furthermore, I chose the option that I as a teacher should only see the best test-score of each student, but by a mistake in the electronic learning system I received a test-score for each trial a student had made. Therefore, if students had answered twice, I had to check trough all test-scores (both the best and the less good) to report to the exam office those who had passed.

Test 2 was made up in a second version similar to test 2 version one in all respects, except that it covered a different part of the syllabus of the same course. Once again I ran out of ideas for questions prior to 100 questions. Now I actively used the option to display additional material from a word-file below the question: for instance one equation.

Test 3 In Fronter, data-base for different groups of questions, automatically scored

Test 3 is a mid-term test of economics in an introductory course of social work, so it is both an exam requirement and the final test in the economics part. As a substitute for an individual 2 weeks-for-work individual paper that had different assignments, the test would have to assess the students’ knowledge about various topics. A straight forward test with only short questions about concepts etc would be a poor substitute. Therefore, I headed for a test consisting of three parts: short questions, questions demanding calculations (household budget, income tax, welfare payment), and questions asking about individual labour supply and microeconomics theory of consumer behaviour. The test was set up using a separate database. In the database questions with answer alternatives were entered in 3 categories: short questions, calculations, theory questions. This way the content of the topic could be tested in a more comprehensive way; to assure that everybody had to answer some questions from each of the three parts. When entering the questions in the database they had to be assigned to the proper subset straight away. For questions with calculations and theory the option to upload additional word-text and figures was used to supplement the question itself. The test itself is then set up to draw at random a certain number (9) of short question for the first part of the test, a number (2) of calculation tasks, and finally a number (1) of theory questions. As long as the test is open, the student can switch between parts and change answers. When they leave the test or the time runs out, the test is automatically submitted.

It turned out that I had started the test without starting it; because I had put timing both in the test and the test folder that were not in accordance with each other. However, checking whether the test was open revealed this problem. Second, upon finishing, the students received information about which questions they had answered correctly, but everybody received the information that they had zero points. So the time saved from automatic scoring was reduced by lots of e-mails from students asking what score had been registered on their tests. This programming mistake has been changed by Fronter. These problems stemmed from using the database approach.

3. Experiences and suggestions

Support staff I benefited from advice from two colleagues who had made up electronic tests in other courses. Furthermore, I learnt a lot from talking to the person in charge of Fronter at my faculty before I started, underway and when tests were opened. When I had entered the questions and responses, he also helped set up and preview all tests, test-run the two versions of test 2, and helped with the problems that occurred when the students got wrong information about their scores in test three. To my experience it is very important to be able to test-run an electronic multiple-choice test before it is opened to a large group of students.

Students were less sceptical towards individual electronic multiple-choice tests than I had expected them to be. However, it is very important to give students accurate and practical information about the test before it is opened to avoid misunderstandings that reduce their actual number of trials for each test. Given that the functionality of showing me only the best test-score for each student was not available in Fronter, I could see how some students in test 3 first did an attempt with low score, later did another with medium score, and finally (close to the closing of the test) passed the test. A test period of more than one week therefore increases the chance that the student will learn enough (from working on the material) to pass. Furthermore, it is also convenient for the student to have flexibility in cases of illness, treatments, trips, hand-ins in other courses etc.. Therefore, in the future I will stick to test periods of more than one week.

How many attempts should a student get? The main idea with a mid-term test is to give students incentives to study properly (attend lectures, read, do exercises, discuss in groups etc) from the start of the semester. Therefore, the student should get so few attempts that each one is considered scarce, and that the student will prepare properly in advance. Millman (1989) indicates how an increasing number of trials increase the chance that the incompetent candidate passes the test, therefore, a large number of trials should be avoided in these mid-term tests. He argues that the passing limit should be raised over time to compensate for an increasing number of trials. For these two reasons a small number of attempts should be given. Furthermore, there may be trouble with PCs, network, servers etc. and ICT-competence varies among students. Secondly, some students are very anxious about all kinds of exams. To reduce anxiety and demand for extra attempts due to technical trouble, more than one trial is recommended. In test 2 students got 2 trials in 2 different tests i.e. 4 attempts to pass altogether. However, most of the students passed the first test version on the first attempt, and since the second test was in a more demanding part of the course, the version 2 of test 2 was more demanding to pass, so the idea of Millman about increasing requirements to pass with additional attempts was implicitly met. Furthermore, for test 3 I told the students that they would get 2 trials when showing them an example test in advance during class. They asked for 3 attempts and got that, so there was an element of negotiation of number of attempts. Given that it turned out that everybody passed within these 3 attempts, ex post, the mid-term evaluation was fully finished in one round of testing.

In response to student demand test 2 version two was reopened as an exercise option prior to the exam, but then nobody kept track of the results. Since it takes almost no time to reopen such a test, it is easy to give an extra test to someone needy, or to use it for extra training. Becker (2000) states that since multiple-choice tests are crude instruments for assessing student learning in economics, they should not be the sole method of assessment in any course. In tests 1 and 2 there was as well the final examination - an individual, written examination in school lasting 3 or 4 hours. However, my experience is that when a multiple-choice test can contain different types of questions with various types of additional figures, equations etc. as in test 3 above, they become less crude instruments of assessing student learning and understanding.

Timesaving To produce the questions for the multiple-choice test was more time consuming than producing questions for group hand-ins or individual hand-ins. Automated scoring reduced hours for marking the electronic multiple-choice tests. However, producing electronic test for the first time meant spending time to learn about the system as such. Therefore, compared to group hand-ins on paper in Test 2, not much time was saved the first year. Comparing Test 3 to individual, large hand-ins, and taking into account the relevant experience from electronic multiple-choice test through Test 2, I think there was a net reduction in teacher hours for Test 3 the first year, despite all the student e-mails about scores that had to be answered. However, to really benefit from electronic testing with respect to reducing the teacher workload, the teacher should be able to use the same setup with only minor adjustments. This means that textbooks should not be changed, and the same teacher should be allocated to the same course the next year(s). In this way the teacher gets an incentive to make the time-investment in electronic testing. This is fully in line with the usual way of reducing time input in teaching and gaining economies of scale – letting a teacher teach the same course the year to come. However, uncertainty about the future tasks of teachers may hamper the diffusion of the innovation of electronic, automatically scored tests in internet-based learning systems. In my institution few teachers use electronic tests, so to have the opportunity to share such resources in the future, at present the first step seems to be introduction of more electronic tests. During an introductory phase the experiences reported in this paper may be of relevance and informative to potential users.

References

Bar-Hillel, M.; Budescu, D.; Attali, Y. (2005). Scoring and keying multiple choice tests: A case study in irrationality, Mind and Society, 4, 3-12

Becker, W. (2000). Teaching Economics in the 21st Century, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol.14, no.1, 109-119

Gipps, C.V. (2005). What is the role for ICT-based assessment in universities? Studies in Higher Education, Vol.30, no.2, April, 171-180.

Millman, J. (1989). If at First you Don’t Succeed: Setting Passing Scores When More Than One Attempt Is permitted, Educational Researcher, Vol.18, No.6, 5-9.

Taylor, A.K. (2005). Violating conventional wisdom in multiple choice test construction, College Student Journal, Vol.39, No.1 (march), 6p

--

i According to Gipps (2005) p.173-4, the efficiency issue (to save staff time in marking) and the pedagogic issue (to enable formative feedback to students) are two of the reasons why we might want to introduce ICT-based assessments.