Digitalized story-making in the classroom

- A social semiotic perspective on gender, multimodality and learning

Håvard Skaar

Research Fellow

Oslo University College, Norway

Email: Havard.Skaar@lu.hio.no

Abstract

The article takes the case of pupils in a fifth-year primary school class (10-11 years old) who use text and pictures in their creative writing on the classroom computers. The study confirms what the research literature indicates, that girls show more interest than boys in writing and story-telling, while boys show greater interest than girls in using computer technology. Social semiotics is used as a theoretical basis for analysing the connection between these differences and relating them to what girls and boys learn. In a social semiotic perspective, learning can be related to the experience of the difference between what we intend to express and what we actually manage to express or mean. In the article, it is argued that social semiotics provides a theoretical basis for asserting that the girls in this case learn more than the boys because they associate themselves with the signs they use through more choices than the boys. The girls, we could say, put their own mark on the signs by coding or creating them themselves while the boys tend more to choose ready-made signs. Ready-made signs require fewer choices than the signs we make or code ourselves. Fewer choices means less experience of the difference between what we wish to mean and what we actually mean, and hence less learning. A pedagogical consequence of this is that boys may be better served by having online work with multimodality of expression organised in such a way that it combines as far as possible the use of ready-made signs with signs they code or create themselves.

Background to the case study and problem addressed

This study describes how boys and girls in a fifth-year school class used writing and pictures when creating narrative on the classroom computers. The research literature points to differences between girls and boys in relation to their interest in writing, story-telling and the use of digital technology. The task given to the pupils served to concretise these differences, which can all be linked to the relationship between signs and experience. Social semiotics concerns how we use signs to give our experience meaning. It thus provides a theoretical basis for analysing how the boys and girls in this case study made use of digitally mediated signs in their story-telling. The interpretation of the results shows that computers assume a different function in the meaning-making process for girls and boys respectively and the findings also contribute to the development of a social semiotic learning theory.

Both national and international research points to marked differences in girls’ and boys’ writing skills (Purves, 1992; Gambell & Hunter, 2000). In the final examinations of the 10-year compulsory school in Norway, girls obtain better results than boys in all subjects, except in mathematics and physical education. The greatest difference is seen in the written Norwegian exams (Vagle, 2005).

The research literature also shows that there are differences in boys’ and girls’ interest in narrative. The same differences are shown in both oral and written discourse. Eriksson (1997) has studied the difference in girls’ and boys’ oral narrative. He states that the girls in his material are simply more interested in story-telling than boys are. Correspondingly, Merisuo-Storm (2006) demonstrates that girls in the fifth school year in Finland are clearly more interested than boys in writing narrative. Eriksson further shows that girls have a greater tendency to express their feelings and subjective evaluations in oral story-telling, while boys tend to report an external event without reflecting over their own feelings in relation to it. Boys describe their own breach of norms uncritically while girls express shame in relation to this type of action.

Correspondingly, numerous studies of written narrative by girls and boys show that girls tend to put greater emphasis on feelings and personal relations while boys tend to emphasise autonomy, competition and aggression (Gray-Schlegel & Gray- Schlegel, 1996; Romantowski & Trepanier-Street, 1987; Tuck, Bayliss & Bell, 1985).It is further shown that girls in the early school years show a greater tendency to relate their narrative to a primary territory, while boys relate it to a secondary territory. In other words, girls base their narrative on personal feelings and experience while boys tend to describe circumstances outside their own realm of experience (Graves, 1973). Berge (2005) has shown how girls in the older classes develop this subjective and emotive form of expression into the forms and conventions of the fictional literature genre. This contributes to their achieving better results than the boys in written Norwegian examinations.

In the present study, these findings are considered in the context of research on gender differences in relation to the use of, interest in and attitudes to computer technology (Durndell, Glissov & Siann, 1995; Vollman, 2005; Endrestad et.al., 2004; Erson, 1992). This research shows that computer technology generally has a greater appeal for boys than for girls. More specifically, boys tend to be interested in technology for technology’s sake, while girls are more concerned with the communicative possibilities the technology offers them (Comber, Colley, Hargreaves & Dorn, 1997; Schofield & Hubert, 1998; Torgersen, 2004).

When pupils compose digital narrative in the classroom, there is a convergence of the activities of writing, story-telling and the use of digital technology. In all these fields, research literature points to differences between girls and boys in attitudes, interests and performance. This study confirms that girls show greater interest than boys in writing and story-telling, while boys demonstrate a greater interest than girls in using computers. The present article will examine the interrelationship between these general trends and interpret them in the light of social semiotics theory. Two questions will be posed:

- What is the difference between girls’ and boys’ story-telling?

- What do these differences imply for girls’ and boys’ actual learning?

Theoretical basis of the study

Social semiotics and multimodality

Ferdinand de Saussure held that the sign is arbitrary and negatively defined. The sign is arbitrary because there is a coincidental connection between the sign’s content and expression, and between the sign and the sign’s referent outside the system of signs. The sign is negatively defined because it obtains its meaning from that which the other signs in the sign system are not. Taking this as his point of departure, Saussure drew up the basis for a structural interpretation of the language system (langue) which had significance far beyond linguistics. Language in use (parole), on the other hand, was not susceptible to systematisation, according to Saussure, and ended up in what Hodge & Kress (1988) calls ”Saussure’s rubbish bin”. In a social semiotics perspective, however, it is the language in practical use, its function in human interaction, which is the basis for theoretical development and analysis.

According to Michael Halliday, the function of language in use is to create meaning. The meaning-making process cannot be separated from its social and cultural context. This is the point of departure for his social semiotics and functional grammar (1985, 2004). Both aspects have been applied as a theoretical basis for analysing gender differences in relation to children’s use of writing (Kamler, 1994; Kanaris, 1999). However, since Halliday restricts his theory building to the spoken language, he does not develop concepts appropriate to the study of gender differences in children’s use of writing together with other types of sign (for example pictures).

His student Günther Kress, on the other hand, in collaboration with Theo van Leeuwen (2001), developed the concept ”multimodal discourse” to incorporate this interplay of different types of sign. They assert that discourse, i.e. the expression of what we mean, will always be multimodal. This means that discourse can only be realised through the simultaneous use of different types of sign, or mode. Writing, for example, is a sign system which must be given material form in order to be read (for example as handwriting or printed letters of one kind or another), and this material form always carries meaning in itself.

Kress & van Leuween relate both digital technology and multimodality, often concretised in their work as the relationship between lay-out, writing and images, to a medial development from page to screen (Snyder, 1997). The media’s digitalisation of different types of sign has consequences both for what we say and how we say it.

In the study presented in this article, the children have been given the task of using the computer to create meaning structured as narrative. The concept ”multimodal discourse” brings together discourse (our “meaning” about something) with the way in which this discourse is expressed (as multimodality). This association is the basis for our analysis of the girls’ and boys’ discursive and multimodal choices when committing their narrative to the computer screen. In the following discussion, the differences that manifest themselves are related to the girls’ and boys’ learning output.

Multimodality and learning

In a social semiotics perspective, it is our use of the sign that gives it meaning. How we express ourselves is not fortuitous. In practice (as parole), the sign in other words is not arbitrary but chosen on the basis of the user’s interests and semiotic possibilities. Kress holds that all use of signs is based on a double metaphor. First we choose some aspect of an object we wish to say something about (it is impossible to say everything and our interests will dictate what it is about the object we want to focus on) and we also choose a sign that represents what we are interested in saying about the object (our semiotic resources determine our range of choices). Kress uses a three-year-old boy’s drawing of a car in the form of circles on a sheet of paper as an example of such a double metaphor: the boy (on the basis of his interests) allows the wheels to represent the car (first metaphor) before (on the basis of his semiotic possibilities) he allows the circles to represent the wheels (second metaphor) (Kress, 2003).

These two metaphorical operations mean that there is no absolute concurrence between what the user of the sign wishes to signify and what he or she succeeds in signifying. The sign is never wholly apt. This gives rise to learning:

“There is, however, a more profound way of seeing the process of semiosis (of making meaning) as a process of learning. In making a representation a person is making a new sign out of what they want to signify, with existing signifying materials. The sign-maker chooses the signifier that is most apt for being the vehicle to represent that which they wish to signify. However, there is never an exact fit, but it is the best possible fit of meaning and form. In the gap between what they meant to mean and what they have to use to mean it exists the possibility of the new; a sign that not only had not been made before, but a sign that wrenches their meanings in unpredictable directions. That lack of fit, and that wrenching, change not only the externally made sign, but also the inwardly made sign in its relation to other signs inwardly held. The new state of all signs now marks the effect of sign-making as meaning.(Jewitt & Kress, 2003 p.13)

Learning in a social semiotics perspective can thus be linked to the experience of what we mean to mean and what meaning we convey. This explains why we often observe that a text improves when we re-write it. At the same time, we also perceive that we express something different when we draw or paint than when we write or sing or dance. This gives a theoretical basis for discussing what the differences between the girls’ and boys’ use of writing, pictures and other signs mean for the learning process they embark on in creating their stories on the classroom computer.

Method

Classroom context

This study was conducted as part of a research project in which I, as one of eight researchers, observed the use of technology in two school classes in Oslo and Bergen. The classroom described here is located in a large primary and lower secondary school (about 480 pupils) in a middle-class area in central Oslo. There were 23 pupils in the class at the time of the study, but, in order for the group to reflect normal variation, pupils being given special follow-up because of reading and writing difficulties were not included. The total number of pupils in the survey was therefore 18, comprising 7 girls and 11 boys. Of the girls, 3 were ethnic Norwegians, 3 had a mixed background and 1 was not an ethnic Norwegian. Of the 11 selected boys, 9 were ethnic Norwegians, 1 had a mixed background while 1 was not an ethnic Norwegian. Because of the pupils requiring special follow-up, the class has two teachers, Roger and Lisa, and a teaching assistant, Sergio. The pupils’ parents have given written consent to the project group’s research results being published in anonymized form.

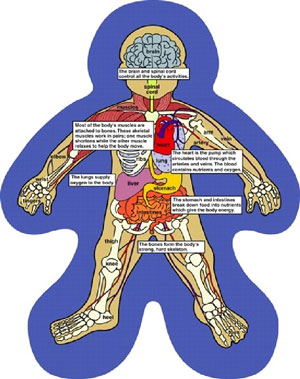

The pupils have 28 class hours a week, of which 5 hours are given to Norwegian lessons and 2 to natural science. I explained to the teachers that I was interested in studying a process in which the pupils used digital technology in the narrative presentation of learning material and came to an agreement with them on the organisation of school hours. The actual story-writing concluded a learning sequence in which the pupils were first made familiar with human anatomy through the teacher’s presentation of the subject, through analogue and digital learning resources and in discussions with each other. After the class had learned in their science lessons how the human body functions, this material was integrated in the pupils’ work through the task of producing their own narrative in their Norwegian lessons. The entire activity was distributed over a total of 14 class hours.

Data collection

My first contact with the pupils and their teachers took place two weeks before the learning sequence began. The other researchers in the project group had earlier in the autumn filmed the pupils’ interaction at the computer over a longer period. On the basis of discussions with my fellow-researchers and my own preliminary observations in the classroom, I selected eight of the pupils: half of each gender and in the teacher’s opinion evenly distributed over three levels of Norwegian language competence: high, medium and low. These pupils I filmed during the learning process in sequences of 2 to 20 minutes duration, a total of 2.5 hours.

I gathered in the stories of all the pupils in the class and for eight of them these texts could therefore be matched against the video recordings and observational data.

An addition source of data is the pupils’ handwritten diaries (logbooks). These diaries had been in use on Monday mornings throughout the school year. The pupils wrote and drew in them freely about what they had experienced over the weekend. When the pupils were using these diaries, the screens would not be filled with digital signs but the jotting paper would be filled with carbon, colour and ink. Contrasted with the pupils’ digitalised narratives, these jotters (in A4 format with stickers, writing and drawings) provide a basis for comparing how the girls and boys in the class express themselves by means of the technologies available to them. In her social semiotics analysis of how 6-year-olds create meaning through drawings, Hopperstad Holm (2002) points to differences in the social and semiotic function of the drawings for the girls and boys she has studied. In the study presented in this article, the use made by girls and boys of analogue drawings in their jotters has also been included, as a contrast to their use of digital images when producing text on the computer screen. This contrast reveals clearly the differences between girls’ and boys’ interest in using writing and pictures when digital representation forms are applied in creating narrative.

The task

Through their Norwegian lessons, the pupils were already familiar with simple word processing and how to retrieve pictures from the Google picture database. The immediately preceding work with tasks on the websites www.naturundring.no and www.norskverkstedet.no would help to create shortcuts to relevant learning resources. (How the body absorbs oxygen and how to write a story).

After the teacher (Roger) had taken them through the topic of how the body takes in oxygen from the air, the pupils were assigned the following task:

”You are going to write a story. Imagine you are an oxygen molecule, called Oggy Oxygen, for example, who gets into someone’s body. What happens? You can illustrate your story with pictures if you want to.”

The pupils’ assignment, then, was to tell a story. The narrative was to be a multimodal discourse in which the learning material could be combined with personal experience and in which the written text could be combined with pictures. In other words, the pupils had quite a free choice as to what the story could be about (discourse) and as to how this discourse should be given expression (multimodal use of signs). The result was that the pupils combined their own experience with the learned facts in various ways and that they combined writing and pictures (and other types of signs) in different ways.

The small-scale qualitative study presented in this article supports qualitative and quantitative findings of differences between girls’ and boys’ interest in telling and writing about themselves and their relations to others (cf. Eriksson, 1997; Merisuo-Storm, 2006; Gray-Schlegel & Gray-Schlegel, 1996). But individual pupils also made choices that clearly deviated from the typical patterns in these studies. In other words, sex and gender did not conform even in this little group. Especially boys participating in girlish cultures have traditionally been subjected to heavy social sanctions. Nevertheless, this choice appeared to be an accessible option for the boys in this study. This might indicate that traditional gendered behaviour is now under a pressure that gives both girls and boys wider scope than before in their reading, writing and use of multimodal resources.

Nevertheless, a comparison of all the stories in the class showed a systemic difference in the discursive and (multi)modal choices the girls and boys made when creating their stories. In the analysis, these general trends are further analysed through a more detailed description of the stories of two of the girls and two of the boys in the class.

Analysis

Discourse: What the girls and boys narrated

All the pupils were faced with discursive choices, since both the subject material and their personal experience were relevant to the story they were to tell. These discursive choices reveal that the girls and boys in the study followed different patterns. Generally speaking, the girls based their story on their own person and/or their own body. They were less concerned than the boys with the need to include concepts and facts from the learning discourse in their stories. Instead, they filled their narrative with a discursive content closer to their own personal experience. The problem the molecule, as the hero of the story, meets in the girls’ accounts, concerns a threat to the body, which is not always specified but which the molecule does its best to deal with. The molecule has other oxygen molecules as friends and it has family members (mother, grandmother etc.) it cares about and is happy to meet. In other words, in the girls’ stories the molecule is personified in a way that gives it emotive associations with others. These associations load the story with meaning and are clearly more important to the girls’ narrative than to that of the boys in the study.

Cathrin, for example, uses selected elements of the learning material to give her story a development in which neither she herself (as a person in the story) or Oggy Oksygen come to any harm. The physiological fate of the oxygen molecule in fact is to be consumed by the body. This breaks with the emancipatory plot typical of the stories children are usually familiar with. But when Cathrin creates a connection between the oxygen molecule, the lungs, heart and blood and her I-person’s intentions and fate in the story, she pays no heed to the oxygen molecule’s real function in the body. She both chooses her own body as the arena for the action and relates her own emotional life closely to the events experienced by the main character, Oggy Oksygen.

The girls associate the events in the story closely with their own identity. By doing so, it is easier for them to choose which events to relate on the basis of their personal experience. In Cathrin’s story, Oggy Oksygen is the I-person (female in this case), and the story angle is firmly maintained throughout the narrative. At the outset, the oxygen molecule is in the classroom where Cathrin is sitting writing her story. The story begins by Oggy Oksygen introducing herself. This is immediately followed in the second line with the names of Oggy’s two best friends, the oxygen molecules Hippe Hydro and Britte Blod. Oggy Oksygen ends up in Cathrin’s ”boy-mad” body by chance, but once inside she manages to sneak past the ”heart’s bodyguard” into the heart chamber, looking for food. She finds ”only blood and meat from the food Cathrin had eaten”, but is also fortunate enough to meet up again with her friends Hippe and Britte. At that point the ”heart guard” moves to throw her out, so she climbs out of Cathrin’s body again. The story ends with her being eaten and spat out by a bird before she falls ”into infinity”.

A discourse linked to personal feelings and experiences can be viewed as an expression of girls’ interest in using the story to explore their own identity. The girls in the study relate to the events in the story as problems or conflicts they must deal with on an emotive basis as these arise. This may help to explain why the girls demonstrate greater confidence than boys in the development of a narrative structure, although this interest alone is naturally not enough to guarantee the girls’ success as narrators.

Maria doesn’t quite succeed. Both the presentation and the figures that populate her story are clearly inspired by the traditional fairy story. Her story tells of an oxygen molecule (Oggy Oxygen and/or another oxygen molecule) the blood cells want to eject from the body because he smells so bad. The oxygen molecule then makes his way to the heart. There he meets the queen and marries her. As king, he helps other oxygen molecules who are in danger of being expelled. In the first sentence of the story, Maria establishes Oggy Oxygen as a helper in her own body but already in the second sentence there is the beginning of an ungrammatical and inconsistent use of pronouns that makes it difficult to place Oggy Oxygen in the narrative development that follows. In fragmentary form, the text recounts a series of emotive events in the fairy-story genre: a love story, a story of mercy, one of ostracization and one of forgiveness. Maria doesn’t succeed in integrating these emotionally-charged events into a coherent narrative but she links them together to make a single text.

The girls’ emphasis on feelings and close relationships is a trait that stands in opposition to the boys’ depiction of external action, associated with speed and combat. Applying Günther Kress’ concept we can say that the boys choose their discourse on the basis of other ”interests” than those of the girls (Kress, 2003, p. 43). The boys’ molecules are third- person figures with implausible skills such as the ability to surf, drive racing cars and so on. The sequence of events in their stories primarily concerns the molecule’s passage through the body. The boys do not describe feelings and intimate interpersonal relations but rather the oxygen molecule’s attempt to fulfil a mission by fighting and beating its adversaries. The main characters generally assume the role of some kind of superhero, but the boys do not always succeed in integrating this superhero in a narrative structure.

Stephen adopts a consistent third-person narrator perspective. The twelve-year-old oxygen molecule Ole Ksygen who ”digs wind-surfing” and is ”sucked into the mouth” of a boy the ”heart’s bodyguards” tell him is dying. Ole finds his way into the heart and learns from ”the leader” there that the boy is about to die and that they need an oxygen molecule able to fly so fast through the body that the oxygen will become ”clean”. Ole performs the task successfully, thereby saving the boy’s life. Ole’s family are happy that he will be breathed out again and inside the body they set up a statue of him in the brain and commemorate him with ”O.Ksygen Day”.

Like Cathrin, Stephen has written a story with a successful narrative structure. His main character assumes a traditional hero’s role inspired by tales of adventure. When his hero wins the day, this is given manifest recognition in the form of a statue. Stephen thus immortalises his oxygen molecule.

In contrast to the girls, the boys do not relate their stories directly to themselves personally or to their own experience. A hero figure acts out the story. In order to carry out the learning task, the boys have to rework the technical discourse into a story. Stephen manages to do this successfully. He creates a narrative structure based on processing the learning material presented and reviewed in class.

Frank, on the other hand, fails to relate to the subject matter and so doesn’t succeed in his story-telling either. His text does not function as a story, even though he begins with a formula taken from a fairy story: ”There was once an oxygen called Bloddy Oksygen ” Three sentences later there are two more narrative sentences: ” Bloddy Oksygen came from a bit of roast beef and into some person or other. The meat was going off. But they ate it all the same.” The rest of the text consists of sentences with informative content although this information serves no function in the story. The main character in the story alternates between being a determined individual and a general phenomenon, and the narrative structure therefore suffers. The product is not narrative but informative, while the factual information about the oxygen molecule is largely erroneous: ”Bloddy Oksygen can help doctors to give blood”, ”If Bloddy Oksygen gets into someone’s brain the person will die.”. Bloddy Oksygen is presented in both the informative and narrative discourse as a bloodthirsty, carnivorous monster with no linguistic foundation in a narrative universe.

Frank is distinguished from Maria (who also has problems connecting the discursive elements in her story) by not being willing in the same way to draw on his own feelings as the basis for the structure such story-telling requires. This might suggest that story-telling is a more demanding task for him in this case than for Maria and the other girls.

The consequence of these gender-specific preferences is clearly seen when the pupils’ stories are compared with their handwritten diaries. The diaries give a chronological account of what happened at the weekend and are not subject to evaluation.(see Polanyi, 1982; Eriksson. 1997). Here it is more difficult to distinguish between the boys’ and girls’ accounts.

Multimodality: How the girls and boys told their stories

When pupils are working at the computer, they are using a type of technology that makes certain forms of semiotic resources available while others are excluded (Kress, 2005). Discursive choices are also reflected through the pupils’ use of these semiotic resources. These include pupils’ use of text, different font types and symbols and their choice of textual organisation, colour and pictures.

Our study looked at the differences between the girls’ and boys’ use of writing with different types of technology at their disposition. In composing stories on the computer, the boys made much greater use than the girls of a combination of writing and other semiotic resources. 9 out of 12 boys in the class found pictures or diagrams on the Internet and pasted them into their stories. Only 2 out of 7 girls did the same. Among the girls, this was done in the two weakest answers but there is no correspondence between the use of pictures/symbols and factual quality in relation to the boys’ answers. The girls in our survey make much less use than the boys of pictures and symbols in their stories.

In relation to the pupils’ handwritten diaries, the opposite is true. There the girls combine written text with drawings and symbols to a far greater extent than the boys. It is also striking to note that, with one exception, all the girls drew pictures of themselves. Only 2 of the 12 boys did this.

When working on the computer, all the pupils, irrespective of gender, used MS Word’s font series WordArt to create an eye-catching title. For the remainder of the text, the girls made much less use than the boys of the possibilities the word-processing software offered them in choosing how to format their text. In their diaries, on the other hand, the boys opted much less frequently than the girls to “design” their writing creatively or enhance it with borders or other decorative features.

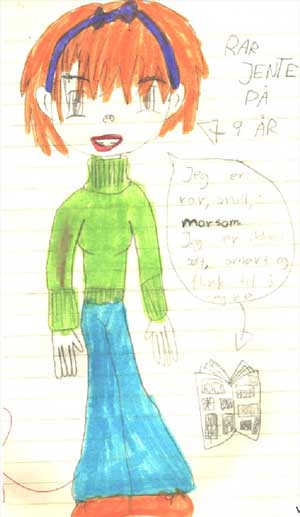

The use of pictures and drawings

Cathrin chose to approach the assignment as a purely written exercise, paying no heed to the teacher’s suggestions about using pictures. Both the teacher and Cathrin herself explained that she also likes writing stories on her computer at home. She expresses clear tastes and preferences and has a self-aware attitude to her own creative ability, which she describes as ”my creativity”. She also likes drawing. At one point in her diary she recounts in relation to a home task that ”I finished a 30-page comic-book I made myself”. Her diary reveals that she takes a keen interest in popular culture in the form of books, TV-series, films etc. She has drawn herself in various versions (Figure 1.1). She draws using a type of line drawing from the comic-book ”Witch”, and in general demonstrates an ability to make personal use of popular culture in a way the research literature often presents as ideal (Buckingham,2003; Willis,1990).

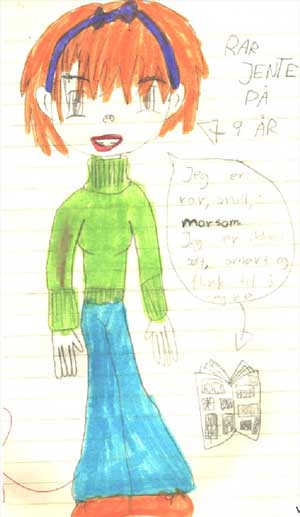

For Stephen the ratio of written text to technology and drawings/pictures is the converse. In common with most of the boys, Stephen has used a picture in his story (Figure 1.2). He has chosen a diagram that shows a schematic presentation of the body’s internal organs. This reinforces the impression that Stephen is more concerned than Cathrin to ensure his story is correct in terms of the factual material presented in class. In the handwritten diary Stephen has kept throughout the school year, however, there are no pictures. He has made only a limited attempt to give his titles some kind of special typographic format. This consists of a faint wavy line above and below the text and highlighting the first letter of every word with a red felt-tip pen. As for other semiotic resources, he has pasted two small stickers into his book (and four on the cover). Cathrin’s diary is decorated with two of the same types of sticker on the front page but the inside is full of drawings and symbols. The portrait of herself which in the digitally mediated narrative is given in writing is conveyed in the diary through a combination of written text, drawings and symbols.

Figure 1.1: Drawing in Cathrin’s diary.

Figure 1.2: Picture in Stephen’s story

(There were no drawings in his diary).

A comparison of their stories and diaries shows that the way in which Cathrin and Stephen use semiotic resources with different technologies at their disposal is typical for the girls and boys in the class respectively. In their diaries, all the girls, with one exception, have drawn themselves at least once (Figures 2.1-2.4).

Figure 2.1: Eva’s drawing of herself.

Figure 2.2: Shabana’s drawing of herself

Figure 2.3: Raya’s drawing of herself.

Figure 2.4: Ida’s drawing of herself.

The boys have generally not drawn as much in their diaries as the girls. Two of the boys have drawn themselves. One boy is playing the violin (Figure 3.1), the other football. The violinist has drawn himself as a violin. The other boy, who is very good at drawing, has drawn himself at the moment he throws himself forward and saves a goal. Both emphasise an action when depicting themselves. This presentation of a self that, as it were, becomes the action the person is performing, illustrates a consistent difference between girls’ and boys’ use of discursive and semiotic resources in the collected data material.

The boys’ choice of semiotic resources means that their own “I” is not revealed. While Frank chooses a Star Wars figure as the protagonist in his story (Figure 3.2), Ikmed chooses to illustrate his diary with figures inspired by the Dual Master cards he collects (Figure 3.3). On the whole, he draws the figures without referring to them in his written text. The boys therefore do not blend the commercialised cultural representation with their own person in the open way Cathrin and many of the other girls do. The figures often have qualities that are so unreal or scary that they quite overshadow the boys’ own identities.

Figure 3.1: The violinist who has drawn himself in his diary.

Figure 3.2: Frank’s picture in his story.

Figure 3.3: Ikmed’s Dual Master drawing in his diary.

Use of written text and font types

In the design of the story’s main heading, the title, there is no clear difference between the girls’ and boys’ choices. Roger has told me that the pupils ”like dressing up their work” and the material gives an unambiguous picture of what devices they choose to use to design or ”embellish” the titles of their digital narratives. Without exception, they use the MS Word font series WordArt to design an eye-catching heading.

In their diaries, however, there is a marked difference between the girls’ and the boys’ interest in working the design of their own writing. The girls put a lot more work into this than the boys do. In Maria’s diary, this embellishment of the writing has a close association with the written description of her own person (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Maria: ”I was quite a little CUTIE with pigtails and make-up bag”.

In the layout of text and pictures, the boys are generally less concerned to comply with textual conventions than the girls are. They make more use of the word processing software’s possibilities but in a way that weakens the structure of their presentation. The research literature points to the fact that boys are interested in technology for technology’s sake while girls are primarily interested in the technology’s communicative possibilities (cf. Comber, Colley, Hargreaves & Dorn, 1997; Schofield & Hubert, 1998; Torgersen, 2004).

In our study, the boys were generally observed to use the word processing system more than the girls in a way that makes it visible, makes it ”stand out” as digital technology (Figure 5.) The way the girls use it, on the other hand, is primarily subordinate to the formal requirements they have learned at school in regard to writing and the use of text and pictures.

Figure 5: How one of the boys explored the possibilities of the word processing system

The relationship between technology and the use of written text and other semiotic resources (pictures, drawings, fonts, symbols) in the girls’ and boys’ meaning-making process can be schematised as in Table 1.

| Technology: |

Girls |

Boys |

| PC |

Low |

High |

| pen/paper |

High |

Low |

Table 1. Girls’ and boys’ use of signs other than writing (pictures, symbols, embellishment) given the availability of different technologies

Discussion

Gender and representativeness

Our study shows that the interests expressed through the girls’ and boys’ discursive choices are also apparent when they use the PC’s digital resources. At the same time, the focus on the selected pupils shows that the relationship between gender and writing (and other types of signs) is a complex phenomenon (Peterson & Calovini, 2004; Peterson & Ladky, 2001). The significance of gender must always be nuanced at individual level. As Thomas Newkirk puts it “Generalizations about gender, because of their scope, are full of holes. Obviously not every child fits them, and most likely no one child fits them all the time. Generalizations about gender at best can only describe tendencies and patterns – not deterministic limitations.” (Newkirk, 2002, p.22).

In the material, John is the clearest example of this. He broke completely with my gender stereotype expectations. In his social life, he mixes more with the girls than the boys, and he writes himself into the typical girls’ universe when in his story he uses his own body as the arena for the action, and also describes himself as ”very sensitive” and ”little me”. To a greater extent than the other boys, he develops a relationship to the corporal, including the taboo-laden repulsiveness (“yuckiness”) associated with blood and bodily processes. John has used a little Disney symbol in his story but no pictures. In his diary, however, he has drawn two girls. They are drawn with the same kind of line and style as the girls in the class use. One is in connection with a visit to the cinema with a girl cousin, the other with a school function (Figure 6).

Figure 6: John’s drawing in his diary

John thus falls into the typical ”girl’s pattern” in his choice of discursive and semiotic resources. At the same time, it is possible to hold that his very atypical-ness confirms the conventional boundaries between the boys’ and girls’ universe revealed in the rest of the material. These conventions are clearly seen in the classroom and are thereby valid in a description of what distinguishes girls’ and boys’ use of computer technology in this case.

At the same time, it is clear that the sample is so small that this use is not representative of others than the pupils in the class studied. Nevertheless, the gender-specific differences manifested in the study in relation to story-telling, writing and the use of digital technology are in line with research findings in other qualitative and quantitative studies. This reinforces the relevance of the study in relation to larger populations.

Kress and Jewitt define learning as the experience of ”the lack of fit” between intended meaning and expressed meaning. This is the point of departure for investigating what the available signs, in the form of digitally mediated semiotic resources, mean for pupils’ learning process in this instance. The study is thereby also a contribution to the development of a social semiotic theory of learning.

What is the difference between the girls’ and boys’ narratives?

In the material as a whole, the contrast between the personal and impersonal creates a gender-based dividing line visible in both their discursive and multimodal choices. In these choices, the girls focus on themselves in a way shunned by the boys. The interest in appearing in their own identity, in revealing themselves in some way through written text and images, is therefore a key to understanding the different ways in which the girls and boys approached the given assignment.

Through their discursive choices, the girls related the narrative to their personal feelings and experience. This can be seen as an expression of the girls’ interest in using the story-telling to explore their own identity and thus also in allowing the story to take on aspects of their own lives.

The girls’ multimodal choices show the same pattern. Regardless of technology, the girls prefer to express themselves through the type of semiotic resources that afford them the best opportunity to make meaning based on their own person and body. On the PC, they prefer to use written text in answering their assignments, not choosing to find pictures and symbols on the Internet to nearly the same extent as the boys. In their handwritten diaries, however, the ratio of text to image is the converse. There the girls combine writing with drawings and symbols much more than the boys do. In contrast to the boys, the girls (with one exception) all draw themselves in their diaries, while they use written text to describe themselves in their digital stories.

In contrast to the girls, the boys do not relate their stories to their own feelings and experiences but to a discourse outside their own sphere of intimacy (cf. Graves (1973), indicating that boys prefer to draw their narrative from “a secondary territory”. It is easier to talk about oneself than about something not known through one’s own feelings and experience (cf. also Gee’s distinction between ”primary and secondary discourse”(Gee, 1999)). From this point of view, it is more difficult for boys than girls to make their chosen discursive material function as a story.

A comparison of the boys’ choice of semiotic resources when working on the computer with the resources they choose to use in their handwritten diaries confirms this pattern. As noted, the boys make much less use than the girls of the possibilities of personalising their entries through writing and drawings. The written text is not elaborated or embellished to any extent and most of the boys draw little or nothing. Those of the boys who choose to draw themselves do not portray themselves as the girls do through emotive relations but through actions and skills.

Correspondingly, the boys’ use of digitally mediated pictures and symbols serves to create a distance between the related events and the boys’ own persons. When free to choose, the boys appear more than the girls to prefer semiotic resources which they do not need to relate to their own body, person and identity. At the computer, they show a stronger preference than the girls for using ready-coded semiotic resources (symbols and pictures), while the girls favour semiotic resources they can code themselves (writing).

What is the significance of these differences for girls’ and boys’ learning outcomes?

An account has been given above of how Jewitt and Kress relate multimodality to learning. They maintain that we learn from experiencing that there is not ”an exact fit” between our intended meaning and our expressed meaning. Different modalities or forms of representation emphasise different aspects of our experience and therefore also represent different forms of learning.

At the same time, learning is also often described as ”the acquisition of knowledge”. Another way of putting it is that learning something means ”making knowledge one’s own”. We succeed in making knowledge our own when we manage to articulate it ”in your own words”, as school exercises put it. In this lies a general perception of learning as the assumption of some kind of ownership over the knowledge-based discourse. This ownership is expressed through the ability to choose how we wish to present it. Different modes (writing, drawing, etc.) offer different options. Our study shows that these choices must also be given a place in a theory of multimodality and learning.

In the written mode, the pupils must make choices so that letters become words, words sentences and sentences text. These choices must at the same time be appropriate to the situational context (the classroom) and the cultural context (the story as genre). When the pupils draw, they do not need to conform to a set of conventional signs (words) but in principle can place each line as they wish. If the choice is e.g. a Star Wars figure, they relate their own person to the sign through a number of consecutive (analogue) choices as the pencil is guided over the paper. If the pupils choose instead to copy a Star Wars figure from the Web into their digital text, they only relate to the figure through that one choice. Both writing and drawing, on the other hand, which the girls tend to prefer more than the boys, require the pupils to make choices on more levels than when they copy digital images into their stories. The use of ready-made signs gives less room for experiencing that there is not ”an exact fit” between what the sign signifies and what the user means to mean.

The interest in ready-coded signs may imply that boys learn less than girls through using signs because they relate less to the signs they choose to use. But in a multimodal text the ready-made codes the computer makes accessible can also stimulate greater use of signs the pupils code themselves, writing for example. Stephen’s picture of the body’s inner organs (Figure 1.2) shows that he has chosen to use an image that reinforces the factual content of his narrative. The image is related to the learning task through the written part of his multimodal discourse. Frank’s choice of a Star Wars figure from the Google database, on the other hand, is a breach of the learning intentions behind the teacher’s assignment of the task. So too is the irony that marks his written discourse. This makes the role of digital technology in relation to Frank’s meaning-making process more ambiguous. On the one hand, Frank uses ready-made signs to avoid personal commitment to the task. On the other hand, the Star Wars figure is part of a multimodal text which also includes the use of writing.

The work of finding ”an exact fit” comprises a number of choices for which the computer helps to set the premises through the access it provides to semiotic resources. It is these choices that determine the extent to which the pupils commit themselves, through investing their emotions and experience, to the story they are recounting.

In our study, the use of digital technology does not compensate for the boys’ failure to reveal their own person in their story-telling. The girls therefore retain their advantage as story-tellers, despite the fact that it is the boys who take the greatest interest in the expressive possibilities available to them through the computer.

Conclusion

The pupils associate themselves with the signs they use through choice. When the signs are ready-made, the choices have already been made. The boys in the study choose, to a greater degree than the girls, to use ready-made signs (in the form of pictures and symbols) in their story-telling. The girls, on the other hand, tend more to code or make the signs themselves. Social semiotics provides a theoretical basis for holding that the girls in the case study learn more than the boys because they associate themselves with the signs they use through making more choices than the boys do. The ready-made signs offered by computer technology require fewer choices. Since the boys tend to prefer this type of sign more than the girls do, and these signs can only to a limited extent be related to their own person through their individual choices, a consequence may be that the boys concerned gain less than the girls from the learning process.

But when considering the differences in girls’ and boys’ use of semiotic resources, we should also take the task given to the pupils into account. The research reviewed indicates that boys generally show less interest in writing stories about themselves than do girls, who by and large are more interested. If this is correct, writing stories normally means to girls the cultivation of an already existing interest, while to boys it quite often means reconciling writing, which does not interest them, with something that in fact does interest them. This is a more difficult task. In the book “Misreading masculinity” (2002) Thomas Newkirk argues that girls tend to outperform boys in literacy tasks in school because school-sanctioned narratives are too narrowly defined to engage boys’ interests. The boys in the study can express their feelings and factual knowledge through digitally provided, pre-coded signs and through writing. Whether their semiotic choices would have been different given another topic or task is an open question. The study simply shows that in this particular case boys tend to prefer pre-coded signs to a greater extent than the girls. In a social semiotic perspective this can imply less learning. It must also be noted that in this particular case writing was the only semiotic resource the girls and boys were able to code. Computers also offer possibilities for meaning-making through coding of e.g. pictures, figures and animations. It can be argued that this generally opens for learning through the coding of these resources in the same profound way as through coding of written language. Instead of encouraging boys to tell more about themselves in same way as girls do, one should therefore use computers to give them the possibility to tell something else, and in a different way.

However, if computers are used in creative writing, we should be aware that the use of ready-made signs can both stimulate and undermine boys’ willingness to express themselves. They may therefore benefit from having their multimodal work on the computer organised in a way that encourages them as far as possible to combine their use of ready-made signs with signs they code themselves.

References

Berge, K. L. (2005a). Skriving som grunnleggende ferdighet og som nasjonal prøve - ideologi og strategier. In S. Nome & A. J. Aasen (Eds.), Det nye norskfaget (pp. 161-188). Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

Berge, K. L. (2005b) Tekstkulturer og tekstkvalitet. In K. L. Berge, L. S. Evensen, F. Hertzberg & W. Vagle (Eds.), Ungdommers skrivekompetanse. Oslo.

Buckingham, D. (2003). Media education: Literacy, learning and contemporary culture. Cambridge: Polity.

Comber, C., Colley, A., Hargreaves, D.J., Dorn, L. (1997). The effects of age, gender and computer experience upon computer attitudes. Journal of educational research, 9(2), 123-134.

Collins, J., Blot, R. K. (2003). Literacy and literacies: Texts, power and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge university press.

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (Eds.). (2000). Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures. London: Routledge.

Durndell, A., Glissov, P., Siann, G. (1995). Gender and computing: Persisting differences. Journal of educational research, 37(3).

Endrestad, T., Brandtzæg, P. B., Heim, J., & Torgersen, L. (2004). "En digital barndom?" En spørreundersøkelse om barns bruk av medieteknologi (No. 1/2004). Oslo: NOVA.

Eriksson, M. (1997). Ungdommars berättande: En studie i struktur och interaction. Uppsala Universitet: Uppsala.

Erson, E. (1992). "Det är månen att nå..." Umeå universitet: Umeå.

Gambell, T., & Hunter, D. (2000). Surveying gender differences in Canadian school literacy. Journal of curriculum studies, 32(5), 689-719.

Gee, J. P. (1999). Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method. London: Routledge.

Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to tell us about learning and literacy. New York: Palgrave Macmillian.

Graves, D. H. (1973). Sex differences in children's writing. Elementary English, 50(7), 1101-1106.

Gray Schlegel, M., & Gray Schlegel, T. (1996). An investigation of gender stereotypes as revealed through children's

creative writing. Reading Research and Instruction, 35(2), 160-170.

Halliday, M.A.K. (1994) An introduction to functional grammar, Second edition. London & New York: Edward Arnold.

Halliday, M. A. K., & Hasan, R. (1989). Language, context and text: aspects of language in a social-semiotic perspective.

Halliday, M.A.K. (1978) Language as social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning. London: Edward Arnold.

Hodge, R. & Kress, G.(1988) Social Semiotics. Cambridge, Polity Press.

Hopperstad, M. H. (2002). Når barn skaper mening med tegning: En studie av seksåringers tegninger i et semiotisk perspektiv. NTNU, Trondheim.

Jewitt, C., & Kress, G. (2003). Multimodal literacy New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

Kamler, B. (1994). Gender and genre in early writing. Linguistics and Education, 6(2).

Kanaris, A. (1999). Gendered journeys: Children's writing and the construction of gender. Language and education, 13(4), 254-268.

Kress, G. (2005). Gains and losses: New forms of text knowledge, and learning. Computers and Composition, 22, 5-22.

Kress, G. (2003). Literacy in the New Media Age. London: Routledge.

Kress, G., & Leeuwen, T.v. (2001) Multimodal discourse: the modes and media of contemporary communication. London: Arnold.

Kress, G. (1997). Before writing: Rethinking the paths to literacy. London: Routledge.

Kress, G. (1993). Against arbitrariness: the social production of the sign as a foundational issue in critical discourse analysis. Discourse & Society, 4(2), 169-191.

Kress, G., & Leeuwen, T. v. (1996). Reading images : the grammar of visual design. London: Routledge.

Merisuo-Storm, T. (2006). Girls and boys like to read and write different texts. Scandinavian Journal of educational research, 50(2), 111-125.

Newkirk, T. (2002). Misreading masculinity : boys, literacy, and popular culture. Portsmouth; NH Heinemann.

Peterson, S. & Calovini, T. (2004) Social ideologies in grade eight students’ conversation and narrative writing. Linguistics and Education, 15: 121-139.

Peterson, S., & Ladky, M. (2001). Collaboration, competition and violence in eighth-grade students' classroom writing. Reading Research and Instruction, 41(1), 1-18.

Polanyi, L. (1982). Telling the American story. New York: Norwood.

Purves, A. C. (1992). The IEA study of written composition II: Education and performance in fourteen countries. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Romantowski, J. A., & Trepanier-Street, M. L. (1987). Gender perceptions: An analysis of children's creative writing. Contemporary Education, 59(1), 17-19.

Schegloff, E. A. (2003). "Narrative analysis" Thirty years later. In C. B. Paulston & G. R. Tucker (Eds.), Sociolinguistics: The essential readings. Oxford: Blackwell.

Schofield, J. W., & Hubert, B. R. (1998). I like computers, but many girls don't. Gender and the sociocultural context of computing. In H. Bromley & M. W. Apple (Eds.), Education, technology, power : educational computing as a social

practice. Albany: State University of New York press.

Snyder, I. (Ed.). (1997). Page to Screen. London: Routledge.

Street, B. V. (1999). The Meaning of literacy. In D. A. Wagner, Venezky, Richard L.,Street, Brian V. (Ed.), Literacy: An international handbook (pp. 34-40). Colorado, Oxford: Westview press.

Torgersen, L. (2004). Ungdoms digitale hverdag. Bruk av PC, Internett, TV-spill og mobiltelefon blant elever på ungdomsskolen og videregående skole (No. 8/2004). Oslo: NOVA.

Tuck, D., Bayliss, V., & Bell, M. (1985). Analysis of sex stereotyping in characters created by younger authors. Journal of Educational Reseach, 78(4), 248-252.

Vagle, W. (2005). Jentene mot røkla. Sammehengen mellom sensuren i norsk skriftlig og utvalgte bakgrunnsfaktorer, særlig kjønn. In K. L. Berge, L. S. Evensen, F. Hertzberg & W. Vagle (Eds.), Ungdommers skrivekompetanse. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Vollman, M., van Eck, Edith, Irma, Heemskerk, Kuiper, Els. (2005). New technologies, new differences. Gender and ethic differences in pupils' use of ICT in primary and secondary education. Computers and education, 45, 35-55.

Willis, P. (1990). Common Culture, Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

1 It could be said that the use of the word ”illustrated” indicates writing as a primary form of expression. An alternative could have been for the pupils to be asked to produce a story in pictures, which would have been closer to the forms of digital story-telling developed in recent years.