The study

The Spring 2003 portfolio

The portfolio consisted of three written essays and a written self-evaluation. Two of the essays were assigned to the students. The third had to be chosen from a list of 16 general topics made available to them at the beginning of the course. On this third essay the students had to specify both question and approach themselves. Before proceeding with writing the essay, their choice of question had to be approved by the lecturer. Students sent their suggestions via e-mail and received a reply within 24 hours. Each essay was to contain a minimum of 1,000 words, but not exceed 1,500 words. A description was presented specifying important issues related to structure and content of the essays. The students were also given a detailed written description of the criteria on which the individual essays and the portfolio would be assessed, and told that they could work together with another student on one essay. Four criteria were described; focus, structure, use of sources, and language. The students were told that the essays should have a clear and well-defined focus, to be kept throughout the discussion. It should be well-structured, balancing details with overview, not giving too much attention to particularities. The students were advised to go to the library and use other sources than the proposed textbook. It was emphasised that they should keep citation to a minimum, but try to use the literature as a basis for their own discussion. We also made clear that misspellings, misuse of literature, and a narrative rather than academic style had to be avoided. All students were invited to a two-hour work-shop at the beginning of the course. In this work-shop we used pieces of texts to illustrate the criteria that had been spelled out. We also commented on some preliminary texts produced by some of the students. Finally, the participants were asked to produce small pieces of texts and asked to discuss them with another participant.

Feedback

A standard feedback form (A 4) giving detailed information related to the four mentioned criteria, was used. Although no mark or grade was given on the individual essay, the person responsible for presenting the feedback indicated whether revision was necessary or not. This was done by ticking off one of three alternatives; ‘needs extensive revision', ‘needs some revision', 'ok as it is' at the bottom of the feedback form. All students were invited to send (e-mail) any queries they might have to me (the lecturer), or to the person whose job it was to present the written feedback. Many students took this opportunity, thus receiving additional feedback. The person responsible for providing the written feedback also acted as one of two examiners marking the portfolios at the end of the semester. The second examiner was external, appointed by the faculty of psychology.

Participants - procedure

In Spring 2003, 483 students signed up for the course, 269 of them exchanging the exam with our alternative. The first essay was introduced one week into the course and the students had to hand in a first draft two weeks later. Feedback was presented the following week. The second essay was presented five weeks into the course, and once again the students had to hand in a first draft two weeks later. Feedback followed the week after. The full portfolio was handed in towards the end of the semester, and was marked as one. The students were advised that the portfolio was not complete unless they handed in a written self-evaluation (500 words), in which they reflected upon their own learning during the course.

In order to investigate whether students did in fact act on the written feedback presented, the person presenting the feedback was asked to suggest a mark (not for the students to know) on the first essay, as it was handed in the first time. A copy of all feedback forms, marks included, was kept until the end of the course. A comparison was then made with the results of this informal marking with the final results on the portfolio as a whole.

Results

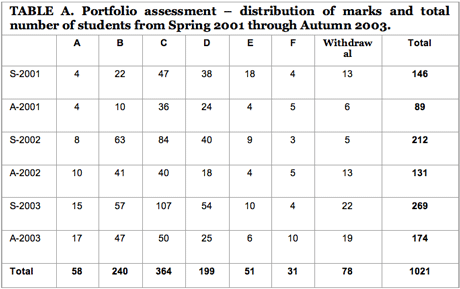

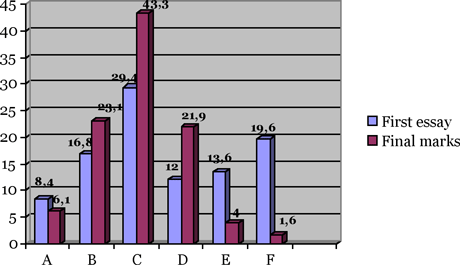

Figure 1 presents an illustration of the comparison between the informal marks and the final marks. The ECTS-marking scale was used. According to the qualitative description laid down by the Norwegian Council for Higher Education, an A is described as "excellent" and represents "An excellent performance, clearly outstanding. The candidate demonstrates excellent judgement and a high degree of independent thinking." B is described as "very good", C as "good", D as "satisfactory", and E is described as "sufficient". According to the qualitative description, an F represents "A performance that does not meet the minimum academic criteria. The candidate demonstrates an absence of both judgement and independent thinking." Students who receive an F have, in other words, failed.

Figure1. Comparing the (informal) marks on the first essay with final marks, Spring 2003. (Figures in percent)

As may be seen from Figure 1, approximately 20% of the students would have failed had the first draft been handed in as part of an exam - as the only essay and marked by this examiner only. This is, in fact, very close to the results traditionally found among students who sit for the exam at these courses (Raaheim, 2003). At the end of the course, however, less than two per cent of the participants fail. We also observe that there has been an upward shift with the marks showing a pattern that is close to a normal distribution. This may be taken to indicate that there is a general learning effect across the three essays. Based on what we know about the positive effects of proper feedback, it seems fair to attribute this development, at least partly, to the fact that the students received feedback on two of the essays.

Discussion

Did the students profit from the written feedback presented to them? The results presented in Figure 1 indicate that this may in fact be the case. Admittedly, there are some methodological weaknesses. The first draft was not subjected to an objective assessment using independent assessors. Instead we relied on the judgements made by the person responsible for giving the written feedback. This person also served as examiner - together with an external examiner - in the final assessment of the portfolios. Besides, we did not ask the students how they used the feedback. This must be taken into consideration when interpreting the results. At the same time it is worth noticing that the person presenting the feedback is among the longest-serving professors of psychology in Norway, acknowledged as one of the nation's top scholars. When asked to present his view on the question he writes:

"After having read more than two thousand essays in social psychology over a period of three years, I was very pleased by being able to conclude that the vast majority of the students clearly demonstrated how the written feedback led to a clear improvement in the end result."

Over the six semesters approximately 90% of the students in the portfolio groups completed the course (ranging between 87 and 98), whereas the same was true for only 40% of the students in the exam groups. It was also found that students in the portfolio groups produced better results than the exam groups (Raaheim, 2003). The great difference in marks and failure rate between students in the portfolio groups and students who followed the regular programme may, of course, be explained in many different ways. One cannot rule out the possibility of a systematic difference, with the portfolio groups consisting of brighter students and/or more motivated students. It is also possible that time (to study) is an important element, as close to all students in the portfolio groups were full-time students, whereas this does not necessarily have to be true for the other groups. All of this can not, however, rule out the fact that nearly 20% of the first drafts in the portfolio group in Spring 2003 would not have passed, and that this is very similar to the picture found over the course of many years at this level among students who do not receive any feedback as they sit for the traditional exam.

The students in our group were allowed to co-operate with another student on one of the three papers. Very few students did, however, grasp this opportunity. Again, there may be many explanations. One may, for example interpret this as a general mistrust in the benefits of co-operation, based on real or imagined events. When asked at the end of the course why they did not choose to co-operate with another student, a very common reply was that they feared that the other person would not do his or her bit. Social loafing is a well-known phenomenon, and it would not be the first time that the fear of "free-riders" would prevent co-operative learning. If one wishes to introduce new ways of teaching and assessment within higher education, and if this implies that students have to work together in pairs or in groups, one does well to acknowledge that students, in general, have little experience in doing so. In order to achieve what Brown (2000) has called ‘social labouring', students need guidance and training in working together. One may also choose to devise a system in which the group takes control and involves all partners, and where stronger students teach weaker students as shown by Bartlett (1995).

As Thompson (1994) argues, a system in which the lecturer presents extensive written feedback to the students may prove to be time-consuming, especially when faced with large groups. In our case we paid an external expert to do this, nearly tripling the costs as compared to the costs associated with the traditional exam. There is, however, much to be saved in time (and money) by refining the feedback procedure. In both our study and the one described by Thompson, students received extensive written feedback. In our case the feedback was presented on a standard feedback form and related to some pre-specified criteria. As one reads many essays belonging to a particular course, one will, inevitably, experience that some mistakes and misunderstandings are repeated. Instead of supplying every student with an individual written feedback, one may use a feedback form with pre-specified categories and simply tick off for a particular category statement. In this way a lecturer may be able to give feedback to very many students in the course of relatively short time. However, the best way to handle this challenge is, probably, to develop a system in which students give feedback to each other. In the Norwegian context this certainly seems to be the correct way to go. A recent study shows that after the introduction of the Quality Reform in 2003, lecturers report that they spend much more time on giving students written feedback on individual papers than they did prior to the reform, and that they have less time to do research (Michelsen & Aamodt, 2006). Such peer feedback would have to be in writing and both receiver and provider should keep a copy of this in their portfolio. The portfolio would not be considered acceptable unless it included both reports. One might elaborate on this, and ask the students to document how they have considered the feedback provided by one or more of their peers. Such a system is well-founded on research, some of it referred to in this paper. There are some prerequisites; students would need to be trained in how to present feedback. This is especially important in introductory courses one might add, as research shows that students in advanced courses are more accurate assessors (Falchikov & Boud, 1989). It is also important that the criteria on which the essay is to be assessed are made explicit to all parties (Dougen, 1996). As is discussed by Orsmond, Merry & Spelling (2006), one ought to also be more careful in evaluating how effective the feedback really is.

Conclusions

In this paper we have tried to shed some light on the relationship between feedback and learning. Feedback is not always helpful to learning. If it is vague, general, focuses on the negative, arrives late, or is unrelated to assessment criteria, it does not do much good. The process of giving feedback to students is time-consuming and/or costs much money. In order to secure best value, assessment criteria have to be spelled out, and feedback must adhere to these criteria. As underlined by Orsmond, Merry & Reiling (2006), tutors ought to also evaluate how effective their feedback has been.

In our study students were supplied with feedback on a standard feedback form, and we argue that the feedback they received was helpful and increased the quality of the written work. We paid an external expert to provide the feedback. In the paper we discuss alternative ways of doing this. One alternative is to make use of the students themselves. In cases where a system of peer feedback is introduced, it is important that students are given training in how to present feedback.

References

Althauser, R. & Darnell, K. (2001). Enhancing critical reading and writing through peer reviews: An exploration of assisted performance. Teaching Sociology, 1, 23-35.

Bandura, A. (1998). Self-efficacy. The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company.

Bartlett, R.L. (1995). A flip of the coin. A roll of the die: An answer to the free-rider problem in economic instruction. The Journal of Economic Education, 2, 131-139.

Bjørgen, I.A. (1989). Ten myths about learning. I: Bjørgen, I.A. (Ed.) Basic Issues in Psychology. A Scandinavian Contribution (pp. 11-24). Bergen: Sigma Forlag.

Bleiklie, I. (2005). Organizing higher education in a knowledge society. Higher Education, 49, 31-59.

Brinko, K.T. (1993). The practice of giving feedback to improve teaching: What is effective? The Journal of Higher Education, 5, 574-593.

Brown, R. (2000). Group processes. Dynamics within and between groups. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Brown, E., Gibbs, G. & Glover, C. (2003). Evaluation tools for investigating the impact of assessment regimes on student learning. Bioscience Education e-journal, 2: November 2003.

Dougan, A.M. (1996). Student assessment by portfolio: One Institution’s Journey. The History Teacher, 2, 171-178.

Falchikov, N. & Boud, D. (1989). Student self-assessment in Higher Education: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 4, 395-430.

Falchikov, N. (2001). Learning together. Peer tutoring in higher education. London and New York: Routledge/Falmer.

Gibbs, G. (2002). Evaluating the impact of formative assessment on student learning behaviour. Invited address: Earli-Northumbria Assessment Conference, 28-30 August.

Hattie, J.A. (1987). Identifying the salient facets of a model of student learning: a synthesis of meta-analyses. International Journal of Educational Research, 11, 187-212.

Jackson, M.W. (1995). Skimming the surface or going deep? PS: Political Science and Politics, 3, 512-514.

Kulhavy, R.W. (1977). Feedback in written instruction. Review of Educational Research, 2, 211-232.

Kulik, J.A. & Kulik, C-L.C. (1988). Timing of feedback and verbal learning. Review of Educational Research, 1, 79-97.

Meyer, L.A. (1986). Strategies for correcting students’ wrong responses. The Elementary School Journal, 2, 227-241.

Michelsen, S. & Aamodt, P.O. (2006). Evaluering av Kvalitetsreformen. Delrapport 1. Kvalitetsreformen møter virkeligheten. Bergen/Oslo: Rokkan-senteret/NIFU-Step.

Myking, I. (2004). Vegen til kvalitet er olja med gode insitament. (The road towards quality is oiled by good incitements). Forskerforum, 7/2004.

OECD, (1997). OECD thematic review of the first years of tertiary education. Country note - Norway.

Orsmond, P., Merry, S. & Reiling, K. (2006). Biology students’ utilization of tutors’ formative feedback: a qualitative interview study. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 4, 369-386.

Raaheim, A. (2003). Ferske erfaringer med mappevurdering. Et eksempel fra psykologi grunnfag ved Universitetet i Bergen. (Recent experiences with portfolio assessment at a first year course in psychology at the University of Bergen). In: Raaheim, K. & Wankowski, J. Man lærer så lenge man har elever (pp. 123-148). Bergen: Sigma Forlag.

Ramsden, P. (2002). Learning to Teach in Higher Education. London and New York: Routledge/Falmer.

Rogers, J. (2001). Adult learning. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Stortingsmelding 27-2000-2001. Gjør din plikt – krev din rett. (Parliament Proposition, no. 27-2000-2001. Do your duty – demand your rights).

Studvest, (2004). Skremt av eneveldig sensor. (Terrified by sovereign examiner). No. 31, 08.12.04.

Thompson, J. (1994). “I think my mark is too high”. Teaching Sociology, 1, 65-74.

Topping, K. (1998). Peer assessment between students in colleges and universities. Review of Educational Research, 3, 249-276.

Weaver, M.R. (2006). Do students value feedback? Student perceptions of tutors’ written responses. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 3, 379-394.

Willis, D. (1993). Learning and assessment: Exposing the inconsistencies of theory and practice. Oxford Review of Education, 3, 383-402.

Wormnes, B. & Manger, T. (2005). Motivasjon og mestring. (Motivation and mastery). Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.