By Stephen Dobson

Email: stephen.dobson@hil.no

Lillehammer University College

Service Box 2626

2601 Lillehammer

Norway

Mini CV:

Stephen Dobson has worked with refugees for 13 years and is currently senior lecturer in education at Lillehammer University College, Norway. His most recent book is Cultures of Exile and the Experience of Refugeeness (2004). Other publications include: The Urban Pedagogy of Walter Benjamin. Lessons for the 21st Century (2002), The Pedagogy of Ressentiment (1995), Baudriallard’s Journey to America (1996). Forthcoming essays (2006): Assessing PowerPoint Presentations; Courting Risk – A Framework for Understanding Youth Cultures. He has published a collection of his own poetry in Norwegian.

Abstract

This essay argues for narrative competence as an underlying skill neglected in educational policy makers’ calls for enhanced literacy through improved reading, writing, numeracy and working with digital technology. This argument is presented in three parts. First, a genealogy of the narrative is presented by looking at understandings of narratives with respect to changes in technology and socio-cultural relations. Three technological forms of the narrative are examined: the oral, written and image based narrative. Second, revisiting Bernstein, narrative competency is connected to pedagogic practice. The focus is upon code recognition and the rhythm of narrative in a classroom context. Third, a proposal is made to develop narrative competence as a research programme capable of exploring literacy in an age of open learning.

The core assertion of this essay is that when narrative is understood in a multi-directional, multi-voiced and multi-punctual sense, opportunities are created for a pedagogic practice that is in tune with the demands placed upon youth and their relationship to changing technologies. This makes the exploration of connections between narrative competence, pedagogic practice and technology the central focus of this essay.

Introduction

It is not uncommon for educationalist policy makers to claim legitimacy for their work by connecting it with the desire to enhance literacy through learning and acquiring specific skills and competencies. Take for example a recent Norwegian government commission on proposed educational reform, where improved literacy is to include reading, writing, oral expression and numeracy, as well as the use of digital technology. These are regarded as fundamental skills based upon the ability ‘to identify, to understand, to interpret, to create and to communicate’ (St. Melding. Nr. 30, 2003-2004/ hov005-bn.html, 3 of 17). However, could it not be argued, as is the goal of this essay, that the competence based upon identifying, understanding, interpreting, creating and communicating rests upon a more essential and fundamental competence, that of narrative competence, such that it is an underlying factor in the above-mentioned forms of literacy? As Ong (1982: 140) has phrased it in his book, Orality and Literacy, ‘in a sense narrative is paramount among all verbal art forms because it underlies so many other art forms, often even the most abstract. Behind even the abstractions of science, there lies narrative of the observations on the basis of which the abstractions have been formulated.’ If this is the case, it will mean that learning to identify, understand, interpret, create and communicate narratives with plots, that are, as I shall argue, potentially multi-accented, multi-directional and multi-punctual will be essential to an enhancement of literacy.

Some initial points can be made about such an argument. Firstly, when literacy is understood in such a wide sense (reading, writing, oral expression, numeracy and with reference to the digital), there is a danger that it might be used to explain all kinds of competence in not just a limited number of subjects, but all subjects. This is especially the case when all subjects might appear to rest upon some form of reading, writing, oral expression, numeracy and digital skills, as argued by Johnson and Kress in their view ‘that multimodal forms of representation exist in all curriculum subjects’ (2003: 11). If the concept of literacy is widened even more, to include the ability to draw on other competencies, then it will eventually become a concept lacking in analytical validity. It will become a descriptive container for the purposes of taxonomy.

Secondly, how should the concept of competence be defined and used? Standard definitions talk of competence as knowledge, skills, abilities and attitudes (Lie, 1997: 33-35). Some are more sceptical. Take for example Kress (2003:49-50) who is against the use of the term competence because in an age of instability we have no practices conventionalized into stability around which curricula and competencies can be developed. However, are competencies so fixed and unmoving as Kress contends? There is a world of difference between the identification of competencies – in list form – and how they are enacted in a flexible manner in everyday lived life. Moreover, if competency is defined in terms of identifying, understanding, interpreting, creating and communicating, as above, then competency becomes a mobile concept, permitting, rather than prohibiting new contents and forms.

Furthermore, it is important to note in defining narrative competency in terms of identifying, understanding, interpreting, creating and communicating plots, my position is closer to the one proposed by Fisher (1987: 65, 75, 115-116). He argued not only that all humans acquire narrative competence in the course of socialization (becoming a ‘universal faculty and experience’), but that it entails forms of argumentative rationality. Thus the identification, understanding, interpretation, creation and communication of narratives with plots that are multi-directional and multi-accented is based upon the use of rational argumentation.

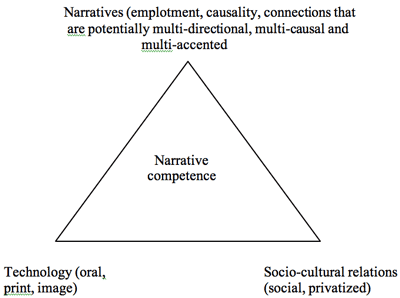

Widening literacy or tightening its reach, fixing competencies or making them fluid? Different positions are possible and in the spirit of a genealogy inspired by Nietzsche, I will ask not what is the truth of a phenomenon, but how and under what socio-cultural and technological conditions does it exist and change. The diagram below summarises these concerns.

Diagram: narratives, technology and socio-cultural relations.

Narratives, according to this perspective, are therefore regarded as essentially temporal and temporality can be described and recaptured in narratives of history and fiction. This kind of understanding is circular as life and narrative mirror each other in a creative mimesis. It also places an emphasis on the necessity of the narrative revealing the ordering of the events in ‘a causal sequence’ (Riceour, 1984: 41).

Ricouer ignores post-modern and hypertext inspired conceptions of narratives (Boje, 2001) that break with the temporal organization of the plot in a diachronic beginning-middle-end and disrupt the direction of causality. In my work with refugees I found instances of narratives where a single narrative beginning was unclear or authorship could not be traced to a single origin. Instead the narratives were multi-punctual in origin and multi-accented because of the polyphonic presence of several voices (Dobson, 2004: 131-4). It is important to note that in such cases, causality was not necessarily absent, but multi-accented and/or multi-directional. Multi-directional can be defined as a narrative that proceeds forwards, as well as backwards in search of an origin. An example of this is what Jefferson (1978: 221) has called the embedded repetition, whereby a narrative repeats a phrase or a topic from a proceeding conversation or non-verbal event, and the repetition functions as a recall of the trigger that set the narrative in motion. This reversal of the causality means that it is not cause to effect, but an effect or several effects in search of a cause and this becomes the focus of the narrative.

These conceptions of narratives, whether rooted in the tradition of Aristotle or the post-modern share what Czarniawska (2004) has called a desire to move from the mere description of events to their emplotment. Secondly, since narratives express sense making in hermeneutic fashion, competing versions are possible. Thirdly, these conceptions are based upon the desire to identify narrative rationality in the events examined (Fisher, 1987: 47, 64, 109). By this it is meant narrative probability based upon a narrative’s coherence (‘whether a story “hangs together”’) and narrative fidelity (expressing a narrative’s credibility based upon ‘good reasons’).

While these definitions provide an understanding of narratives that are multi-directional, multi-punctual and multi-accented, there is a danger that they are timeless in the sense that changing technologies and socio-cultural relations supporting different kinds of narrative are neglected. For this reason, a genealogical analysis is necessary in order to elaborate upon and provide a context for the multi-directional, multi-punctual and multi-accented conception developed above. Genealogy, in the spirit of Nietzsche (1969), seeks to understand the changing conditions, in this sense technological and socio-cultural, that support the life and death of a particular phenomenon, in this case narrative competence. In other words, to arrive at a closer understanding of narrative competence, understanding narratives as multi-directional, multi-punctual and multi-accented, is only one part of the answer. It is necessary to consider in addition the role of technology and the socio-culture relations that accompany it as these narratives are created, communicated and interpreted.

Walter Benjamin in his essay The Storyteller (1992), provides some insight into these matters. He focused on the changes brought about in narratives as the socio-cultural relations of the oral were challenged by the arrival of print. The oral tradition of narratives praised by Leskov, Hebel, Gotthelf and Poe had relied upon the corporeal presence of the storyteller. To use the words of Levinas (1969:67), ‘meaning is not produced as an ideal essence; it is said and taught by presence’. All this changes with the arrival of print technology. Narrative and its socio-cultural relations gain a different form when expressed in novels or in newspapers.

For Benjamin (1992: 99), the novelist has isolated himself and the reader meets the novel on his/her own. Benjamin argues that the novel does not provide advice on the living of life. Instead the novel compensates for life and the reader hopes the novel can provide a way of ‘warming his shivering life’ (1992: 100). Not all would agree with his view, but his main point is that the culture and technology of the novel involves a one-to-one communication, where the reader and writer are separated by distance and time. This precludes a spontaneous development of the meeting between the two. For Ong (1982: 150, 153), this is also connected with the inward turn of narrative, as authors are concerned with the ‘interior consciousness of the typographic protagonist’ and engaging the reader’s ‘psyche in strenuous, interiorized, individualized thought inaccessible to oral folk’.

The second competitor to the narrative communicated in oral fashion is the narrative found in newspapers. This kind of narrative has as its goal what Benjamin calls information. It is characterized by ‘prompt verifiability’, unlike the oral narrative with its validity sometimes lying elsewhere in a different place and time (e.g. an experience from a long time in the past). Secondly, it has to sound plausible, unlike the narratives of the storyteller, which can draw upon the miraculous. Benjamin emphasizes a third characteristic of the informative narratives found in newspapers, ‘no event any longer comes to us without already being shot through with explanation’ (1992: 89). It is the expert communicating the narrative who proposes the interpretation and this is in stark contrast to the oral narratives of the storyteller:

Once again, not all would agree that the narratives of the oral storyteller contain no interpretation, especially when the storyteller leaves their own personal mark on the narratives communicated and the very presence of emplotment suggests the presence of interpretation. Nevertheless, the main point is that information is more likely to interpret the narrative presented before it reaches the recipient.

What we can learn from Benjamin is that the opportunities for the recipient of the narrative actively giving a response to the teller of the narrative change with the move from the oral to printed narratives. The oral narrative relies upon a competence that is more social, open and spontaneous than the more privately directed, reflective printed narrative. This means that in the case of the oral narrative the listener is potentially able to exert an influence on the narrative as it is recounted, adding their voices, interpretations and understandings. The narrative can become multi-accented. It can also become multi-directional and multi-punctual as the listeners draw attention to new points and directions in the narrative not anticipated by the teller.

The kind of narrative competence required with the oral narrative requires that listeners learn and have the opportunity to interrupt the narrative as it unfolds. It is this socio-cultural character that is lost with the printed narrative, even if newspapers are read in the presence of others, they cannot influence the narrative read in the same manner. We are still talking about the same competence to identify connections, emplotment and so on, what changes are the socio-cultural relations.

With the arrival of image based narratives digital technology is important. It makes possible what Kress has called the dominance of the screen:

The character of socio-cultural relations supporting narratives change once again. While the image based narratives of films are presented to the viewer in completed form, as was the case with novels and newspaper reports, the internet makes it possible for the receiver of the images to once again interrupt the person constructing and communicating the narrative. This is the case in constructive hypertext, where all are able to contribute to the narrative as it unfolds (Svarstad, 2005: 84). Hypertext can be multi-modal, making use of images, text and other modes of communication (Kress, 2003). This makes it possible for the reader or viewer to examine the hyper-text in an order different to the left to right, top to bottom, that was dominant in western printed text.

The narrative becomes multi-directional, multi-punctual and multi-accents and the narrative competence required still involves making connections, revealing and making lines of emplotment, identifying causal relations. But, now it is a more open process and the connections, emplotment, causality can be multi-modal in character, following the logic of time (dominant in print as the page is read) and space (dominant in the view of images)

To summarise, with the oral, the narrative competence required to make connections, engendering emplotment and causality is supported by socio-cultural relations that enhance the opportunity to create multi-directional, multi-punctual and multi-accented narratives. Narrative competence dies somewhat, but not totally, with the arrival of print technology. The opportunities for interruption are restricted and socio-cultural relations are more privatised. With the rise of media of the screen, narrative competence is brought back to life once again and becomes potentially more open and involving. The kind of narrative competence required changes. Now it is the use of different modes, such as written and image based, and their mixed usage that provides the foundation for the identification of connections, emplotment and causality that can once again become multi-accented, multi-punctual and multi-directional.

The diagram introduced in the introduction summarises the argument of part I: narratives and narrative competence are related to technology and the socio-cultural relations supporting technology. Understanding narrative competence as being able to identify multi-directional, multi-causal and multi-accented emplotment, causality and connections, is not therefore enough if technology and socio-cultural relations are ignored.

Part II: Literacy and pedagogic practice

In this part of the essay, narrative competence and its relations to technology and socio-cultural relations are connected with pedagogic practice and literacy. Let us start with an example: students are presented with the following page

(http://www.trentu.ca/jjoyce/fw-308.htm)

from James Joyce’s novel Finnegans Wake. (1975: 308) They are asked it identify the narrative.

It is to be expected that the teacher will be met with initial silence. Perhaps one student is familiar with other works by Joyce and hazards a guess that Joyce was attempting to follow up an earlier book, Ulysses, with a different kind of book. This student is searching for a way into the text, seeking to find connections between Joyce the writer of other books and this book. Put differently, the student is seeking to identify a possible emplotment for the events presented by Joyce. To assist the teacher tells the class that Joyce wanted the reader to have to struggle with the text and images. They represented events and the reader had to make connections between them in order to identify the plot. Finnegans Wake has a plot, but it is hard to pin it down and it changes as different connections are made or dissolved: at times it is about a family (publican, wife, two sons and daughter), at times it is about the river Liffy flowing through the centre of Dublin, sometimes it is about world history, on occasions it is about world religions. The plot changes, reverses and recurs.

Thus one plot, and not the only one, that can be found or created from the events of this page (and previous pages) is the following: Three children have been in the nursery doing their homework. They have been learning about war and procreation as two principles in world history and everyday family life. The ten monosyllables in the centre of the text represent the descent from God into the physical world - the first three are the holy trinity (mirrored in the words of the left margin), the next three are human trinity, followed by the trinity of the physical world (in the left margin as: time, space and causality) In the right hand margin the kids are called for tea and cocoa. The two images: the uppermost is of a nose representing spirit exhaled into the world with creative force. The hand against the nose can denote the two brothers battling. The cross bones suggest death, but are also associated with love (in Hinduism, the God of love is also the God of death) The X of the crossbones can also represent kisses and crucifixion (Campbell and Robinson, 1954: 162-163).

These are only a few of the possible connections and Joyce did not intend there to be one single set of a priori ‘true’ connections. The line of causality and emplotment is open to change and reversal. In the context of this essay, it is an example of a multi-directional, multi-punctual (i.e. multiple beginnings, ends) and multi-accented narrative that combines text with images and has a changing musical rhythm if read aloud. It pre-dates the arrival of hypertext, normally defined in the following manner and assumed to have its origin in the 1960s:

However, as argued above the narrative and the narrative competence required in its identification and creation is also dependent on the technology and socio-cultural relations in which it is communicated. In line with this view literacy is extended to include the role of technology and socio-cultural relations as student’s encounter printed texts and images and attempt to reveal or construct narrative connections, emplotment and causality. Not all teaching resources provide Joycean, narrative dilemmas for students, but parallel experiences and resources can easily be identified. For example, when students are asked to search on web-pages designed according to the principles of hypertext.

With respect to technology, Finnegans Wake despite being in the form of a book and not on the internet, combines text with image and is multi-modal. As to the socio-cultural relations desired by Joyce, his intention was that they should be open and no one person would be able to say they have understood the plot in a once and for all definitive manner.

As to the embodiment of social relations, the teacher is thus no longer able to claim supreme knowledge and authority about the book and its narrative. Having said this, Joyce’s book does not make it immediately easy for the student who wishes to make narrative connections, identify plots and lines of causality. The teacher is still required, perhaps more as a guide and tutor than as a one-way communicator of a single narrative truth to be unquestionably accepted. The socio-cultural relation between the teacher and the student is maintained and with this in mind it is fruitful to look at Bernstein’s reflections on these relations and also on what he calls the ‘rhythm of narrative’.

To understand what is going on in the classroom, Bernstein developed a theory of codes and connected it to the socio-cultural relations of the classroom:

Hierarchal rules refer to the manner in which the acquirer and transmitter enter a relation, usually with the transmitter in the dominant position. Sequencing rules: something must come before and something after the transmission. Sequencing rules also entails a pacing. Such as quick teaching, with fewer opportunities for examples, illustrations and narratives, which require a slower pacing. Criteria rules ‘enable the acquirer to understand what counts as a legitimate or illegitimate communication, social relation, or position’ (2004: 198). The Hierarchal are regulative rules, while the sequencing/criteria are discursive rules.

When pacing is strong ‘we may find a lexical pedagogic code where one word answers, or short sentences, relaying individual facts/skills/operations may be typical of the school class of marginal/lower working-class pupils, whereas a syntactic pedagogic code relaying relationships, processes, connections may be more typical of the school class of middle-class children, although even here pupil participation may be reduced’ (Bernstein, 2004: 207). In the latter, the code is more elaborated and explaining principles, in the former the emphasis is on specific operations that develop low-level skills.

Bernstein’s point is that when pedagogic practice utilizes a lexical as opposed to a syntactic pedagogic code, teachers and pupils will focus upon different things in the subjects taught. The latter syntactic coding is more suited to developing narrative competence because of its emphasis on identifying, understanding and interpreting ‘relationships, processes, connections’. In the context of my argument, narrative competence as a signifier of literacy, becomes connected with an awareness of the codes that can be used to understand specific subjects and what it means to become competent or skilled in them. Thus, the syntactic code might enhance narrative competence to see connections and plots, or do the opposite, when it is a lexical code. Thus, understanding the code or codes in Finnegans Wake makes it possible to understand its multi-directional, multi-punctual and multi-accented narratives.

At the same time, Bernstein complicates, or even confuses his argument, when he argues that, ‘the rhythm of narrative is different from the rhythm of analysis’ (Bernstein, 2004: 206). By this he means that the latter’s strong pacing rests upon a principle of communication that is very different from the ‘communication principle children use in everyday life’. Not only does it imply less time for the unfolding of narratives with images and digressions, it also privileges less ‘everyday narratives’ in the classroom.

Against Bernstein, it might be argued that the rhythm of narrative is more suited to a syntactic pedagogic code, where relationships, processes and connections between events are in focus. If this is the case, then it becomes hard to sustain the distinction between a rhythm of narrative (considered dominant outside of the classroom) and a rhythm of analysis (considered dominant in the classroom). Both become interlocked. Thus, children in telling narratives or listening to narratives outside of the classroom are already making use of a rhythm of analysis as they contemplate or make connections between events.

Apart from these more critical reflections on Bernstein’s essay, his emphasis on codes is important to the argument of the essay because it highlights how the codes adopted by the teacher in an educational situation can invite the making of narrative connections between events, or the opposite. Put differently, the codes exert an influence upon both the opportunity to construct or interpret narratives and the kind of socio-cultural teacher-student relations used to communicate these relations.

Moreover, reading print or reading images can be regarded as different codes, where the logic of time is dominant in the former (i.e. words must be read in a specified, temporal order) and the logic of space is dominant in the latter (images or blocks of words embedded in an image can be read in different orders). In the example of the page from Finnegans Wake, code switching is required as the move is made between the images and the printed words. Kress has highlighted the importance of this:

Transduction is the term Kress (2003: 47) uses to denote the movement between codes, as contents are re-interpreted into the logic of the respective media. It may also be a case of not just code switching, but the development of ‘crossover and hybrid forms’ (Kell, 2004: 440). For example the visual skills of ‘linking, decomposing, reorganising elements’ (Jewitt, 2003:97-98) can be reintroduced into the writing and reading of a text with visual elements.

What have these arguments to do with literacy? Literacy is in my opinion to do with not only the competence to identify narrative connections, emplotment and lines of causality that are multi-directional, multi-accented and multi-punctual. It is as much to do with the socio-cultural relations, in this case embodied in the practice of the teacher, as codes are selected to afford the student with a greater or lesser opportunity of enhancing their narrative activity. The practice of the teacher can be understood, in the spirit of Bernstein, as founded on code selection, such as lexical and syntactic codes. The code selection can also refer to the different technologies, which have historically been dominant, respectively print and image and how they rely upon different logics (temporal and spatial). To be literate is to be able to use and recognize the different codes, and the enhancement of literacy is to increase this skill in code use and recognition.

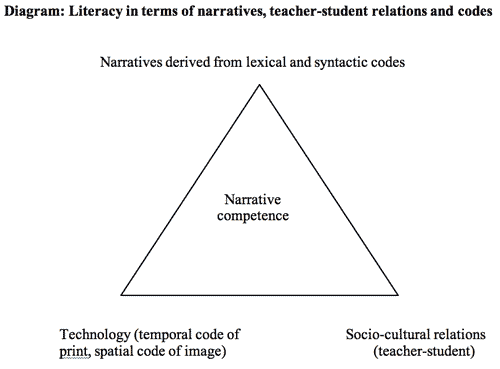

In Part II, narrative competence has been explored in terms of the socio-cultural relations of the pedagogic relation between teacher and pupil and how these are connected with different forms of codes. The combined effect of the codes, relations and effect upon narrative competence provides a view of literacy that incorporates these dimensions. The diagram introduced in the introduction can be re-cast to illustrate this:

Part III: Narrative competence as a research programme enhancing literacy

The challenge, as defined by educational policy makers, exemplified in a Norwegian white paper (St. Melding. Nr. 30, 2003-2004), is to enhance literacy through reading, writing, oral expression and numeracy, as well as the use of digital technology. Fritze, Haugsbakk and Nordkvelle (2004) have highlighted how this might entail an instrumental view of not only technology, but also different teaching media (reading, writing and so on). What they ask for is a greater emphasis on how different media can support the bildung (formation) of the individual throughout life. To realise this greater awareness is required of the manner in which we learn about reality through these media. Put differently, media mediate our relation to reality and a focus on this relation reveals the parameters and details of a pedagogic project for policy makers and teachers alike.

My argument is also in line with their general view, in the sense that the concept of narrative competence seeks to account for the manner which reality is mediated in different media, such as the written, through images or orally. But, narrative competence represents only one research programme for understanding the mediation of reality. Others might be possible, such as the one inspired by Qvortup’s (2003) work on Luhmann’s system’s theory and the hypercomplex society.

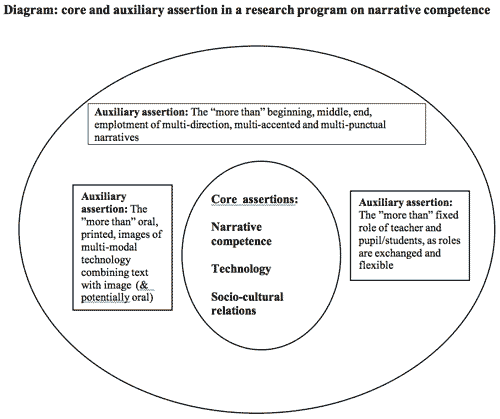

A research program - Lakatos’s phrase (1970: 132-133) - entails a hard core of assertions (his term was hypotheses), a protective belt of auxiliary, less strong assertions, a positive heuristic (suggesting paths of research to pursue) and negative heuristic (telling ‘us what paths of research to avoid’). Lakatos restricts negative heuristic to the core assertion, which is not to be problematised, and positive heuristic to the questioning of the auxiliary assertions. I would contend instead that the core assertion can also be researched in a positive heuristic manner – with the goal of not necessarily questioning its validity, but of increasing our understanding of it. In addition, auxiliary assertions can be examined from the viewpoint of a negative heuristic in order to protect them - asking what is necessary for assertions to hold, rather than be questioned and modified or abandoned.

In this essay, the core assertion of the research program is that there is a connection between narratives, technology and socio-cultural relations. The last mentioned understood as a set of culturally defined relations between teachers and students/pupils. The protective belt auxiliary assertions are the assumptions connected with each of these core points. Thus, for narratives and the competence entailed in creating and using them refers to narratives which can be more than simply beginning, middle and end with emplotment and a causal interpretation of the relation between events. Narratives can be multi-directional, multi-accented, with different voices, and multi-punctual (with multiple beginnings or ends). The auxiliary assertions for technology can be more than the oral, the printed and the image with its emphasis on screens. It can be the manner in which technology has become, what Kress has called multi-modal, combining the printed with the image, and potentially also including the oral. The auxiliary assertion for socio-cultural relations can be, with respect to pedagogic practice, more than the fixed roles of teacher and the student/pupil as passive recipient learning the codes of the narratives. It can be the flexible role positions, as the pupil/student adopts the role of teacher and the teacher as pupil. The diagram below portrays these core and auxiliary assertions.

The ‘more than’ component of these auxiliary assertions enhances and defines the parameters of the openness of the learning that takes place, and mastering in turn these assertions in a practical and theoretical manner enhances the literacy and narrative competence of participants in the educational context. In part II, the argument was made that this was to do with using and recognizing codes to create, identify, interpret and understand narratives such that code mastery becomes an expression of literacy. If these core and auxiliary assertions – in terms of a positive and negative heuristic – are further researched, then it will possible to further clarify narrative competence as a research programme.

Conclusion

The goal of this essay has been to loosen up and widen our conception of the narrative and the competence that accompanies such an understanding. The argument made has been that if this understanding of narrative is combined with an awareness of changing technology and socio-cultural relations, it will be possible to re-conceptualise literacy. Literacy, normally understood to include reading, writing, oral expression and numeracy, as well as the use of digital technology will then be re-positioned to rest upon a competence in narratives. This competence is in turn connected with the technology and socio-cultural relations mediating the narratives. Put differently, reading without narrative competence and awareness of codes and technology will cease to be reading and the same applies to the other kinds of literacy.

A second goal in this essay has been to demonstrate how narratives and the competence they generate cannot be divorced from the technology and socio-cultural relations supporting their mediation. This is important to underline because it opposes the view that the narratives and narrative competence can be studied as timeless, universal phenomena; sufficient in themselves and independent of technology and socio-cultural relations.

Put simply, this essay has been predicated on the belief that a wider use for narratives can be found and justified in educational practice. It might be contended that teachers already possess and use narrative competence. Against this it might be asserted that if this is the case, it is a largely taken for granted competence and reflection upon it is still necessary to bring it to consciousness, so it can be communicated and taught to pupils in an open manner.

Bibliography

Aristotle (1965): On the Art of Poetry. Translated by T.S. Dorsch. London: Penguin.

Benjamin, W (1974-89): Gesammelte Schriften. Edited by Schweppenhäuser and Rolf Tiedemann. Frankfurt: Frankfurt am Main.

Benjamin, W (1983): Charles Baudelaire. A Lyric Poet in the Era of High Capitalism. London: Verso Books.

Benjamin, W (1992): The Storyteller. In, Illuminations. London: Fontana.

Bernstein, B (2004): Social Class and Pedagogic Practice. In, Ball, S. (editor) the Routledge Falmer Reader in Sociology of Education. London: Routledge Falmer.

Boje, D (2001): Narrative Methods for Organizational and Communication Research. London: Sage.

Campbell, J. and Robinson, H (1954): A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake. London: Faber and Faber.

Czarniawska, B ( 2004): Narratives in Social Science Research. London: Sage.

Dobson, S (2004): Cultures of Exile and the Experience of Refugeeness. Bern: Peter Lang.

Fisher, W (1987): Human Communication as Narration: Towards a Philosophy of Reason, Value and Action. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Fritze, Y., Haugsbakk, G. and Nordkvelle, Y (2004): Mediepedagogikk (Media Pedagogy). In Norsk Medietidsskrift, vol.11, no.3., s206-214.

Goodwin, C (1984): Notes on Story Structure and the Organization of Participation. In, Atkinson, M. and Heritage, J. (editors) Structures of Social Action. Studies in Conversation Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jefferson, G (1978): Sequential Aspects of Storytelling in Conversation. In, Schenkein, J. (Editor) Studies in the Organization of Conversational Interaction. New York: Academic Press.

Jewitt, C (2003): Re-thinking Assessment: Multimodality, Literacy and computer-Mediated Learning. In, Assessment in Education. Vol. 10, no. 1.

Johnson, D. and Kress, G (2003): Globalisation, Literacy and Society: Redesigning Pedagogy and Assessment. In, Assessment in Education. Vol. 10, no. 1.

Joyce, J (1975) [1939]: Finnegans Wake. London: Faber and Faber.

Also: http://www.trentu.ca/jjoyce (4.11.04)

Kell, C (2004): Review of Literacy in the New Media Age. In, E-Learning. Vol. 1, no. 3.

Kress, G (2003): Literacy in the New Media Age. London: Routledge.

Kress, G (2005): English for an Era of Instability: Aesthetics, Ethics, Creativity and ’Design’. Unpublished lecture, Institute of Education, London. January 18th.

Lakatos, I (1970): Falsification and the Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes. In, Lakatos, I. and Musgrave, A. (editors). Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Levinas, E (1969): Totality and Infinity. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press.

Lie, L (1997): Strategisk Kompetensestyring (Strategic Management). Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

Nietzsche, F (1969): On the Genealogy of Morals. New York: Vintage Books.

Ong, W (1982): Orality and Literacy. The Technology of the Word. Florence KY: Routledge.

Qvortrup, L (2003): The Hypercomplex Society. New York: Peter Lang.

Ricoeur, P (1984): Time and Narrative. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Svarstad, A (2005): Pedagogikken og det Digitale Paradigme (Education and the Digtial Paradigm). Unpublished Master in Education, Lillehammer University College, Norway.

St. Melding nr. 30: Kultur og Læring (Culture and Learning), 2003-2004,

http://odin.dep.no/ufd/norsk/publ/stmeld/

045001-040013/hov005-bn.html. (4.11.04)