A long way? Introducing digitized historical newspapers in school, a case study from Finland

Author

Inés Matres García del Pino

Faculty of Arts / Department of philosophy, history, culture and art studies

University of Helsinki

Email: Ines.Matres@helsinki.fi

Address: Sörnäisten rantatie 8, 00530 Helsinki, Finland

Abstract

Newspapers help teachers to connect their classes with the real world. Their role in education is widely researched, but the use of historical newspapers has attracted little attention. Using social practice theory, this article examines the practices they enable, and how such practices relate to the skills and knowledge upper-secondary students are expected to acquire in school. These questions are pertinent today, as the digitization of newspaper heritage is generalizing access to materials traditionally considered for scholarly research. My approach is ethnographic, involving in-depth interviews, focus-group discussion, and participant observation. The teachers’ accounts motivated me to consider the tradition of using newspapers in school. The class projects demonstrated that historical newspapers reflect attributes that make present-day newspapers popular. Closer examination of students’ work demonstrated that the digital library that houses historical newspapers facilitated and constrained the students’ freedom and capacity to go deep when conducting research. The main finding is that historical documents can support the students’ digital skills. By considering digitization and preservation processes of media heritage, the scope of media education can be widened from its focus on production and consumption. In practice, a better understanding of these materials, will help educators give adequate guidelines to their students.

Keywords: newspapers in education, historical newspapers, digital libraries, upper-secondary school, case study.

Introduction

“Carrying out a practice very often means using particular things in a certain way. It might sound trivial to stress that to play football, we need a ball and goals as indispensable ‘resources’. Maybe it is less trivial to point out […] that writing, printing and electronic media ‘mould’ social practices, or, better, they enable and limit certain bodily and mental activities, certain knowledge and understanding as elements of practices.” (Reckwitz, 2002, pp. 252–253)

My research is concerned with uncovering the significance of digital cultural heritage to the school community, in the interests of both teachers and students. Significance in this article refers to the understanding and knowledge that emerge in school through the use of digitized historical sources. Digital cultural heritage, in turn, is understood both as a product of the digitization of collections undertaken by institutions such as libraries, archives and museums; and as the forms of presentation and access to these materials. The concept of ‘practice’, as formulated by Andreas Reckwitz in his cultural theory of social practice, fosters an understanding of historical objects in the context of their current use. To illustrate this practical significance of historical materials in the setting of a school classroom, I present a case study that examines how teachers and students at an upper-secondary school in eastern Finland made use of historical newspapers contained in the digital collections of the National Library of Finland.

Faced with the fact that the idea of using historical newspapers was new to most of the teachers in this school, my initial concern was to find out if such materials, and especially those preserved in the digital collections of the National Library, could be of use to this community. In order to answer to this question, this article examines digitized historical newspapers in relation to the concept of practice. On a more concrete level, this article aims to uncover how the practices enabled by historical newspapers relate to the habits of teachers, and to the activities that students undertake for their assignments. Following Reckwitz’s understanding of practices and how they are molded by the things we use, I also relate my main findings to the concept of literacy, that is, the knowledge and skills that students are expected to acquire from these materials.

The lack of experience with these historical materials among teachers contrasts with their frequent use of newspapers in their teaching. In the first part of this article I consider the similarities and differences in today’s and historical newspapers as school material. This comparative approach surfaced during interviews in which teachers described how they prepared and carried out activities related to contemporary and historical phenomena. Seven of the eight teachers I interviewed mentioned newspapers as a tool for dealing with contemporary phenomena. This supports existing research about the extensive use of newspapers in Finnish schools (Gröhn, 1981; Hankala, 2011; Puro, 2014). According to the teachers’ first reactions to historical newspapers, I observed that the class activities they describe using contemporary newspapers, could provide a framework within which to develop activities using their historical equivalents.

To find out how these historical materials shaped activities in the school classroom, I observed three course sessions in which students used the digital newspaper collection of the National Library, and presented their projects. The content of the students’ projects ranged from advertisements and celebrities to the Finnish Winter War, and other significant events in history. Their presentations showed how the students related them to their personal, school and even professional interests. In the second part of the paper I examine more closely how these historical documents facilitate and constrain activities in which students regularly engage, affecting the way they learn. These affections, have been researched within the field of history teaching (Friedman, 2006; Lévesque, 2006; Nygren & Vikström, 2013). In this context, digital primary sources have been designated suitable for teaching students in “following the footsteps of a contemporary historian” (Nygren & Vikström, 2013, p. 67). However, this case study presents a media project organized by a language and literature teacher, which provides a new perspective that calls for the recognition of other potential uses such materials might have.

The last section of this paper opens a dialogue to consider the contribution of media heritage and its preservation to media education, which is concerned with teaching and learning with and about media industries, messages, audiences and effects (Buckingham, 2003; Martens, 2010; Hankala, 2011; Vesterinen, 2011). This is a dialogue that concerns many teacher groups, as it resonates with multidisciplinary transformations in the school curriculum (Opetushallitus, 2015, p. 220 and ff.). At the same time, this case study should encourage institutions such as national libraries that are actively involved worldwide in digitizing and generalizing access to historical newspapers, to promote alternative uses of materials that have traditionally been considered suitable for academic research (Brake, 2012; Gooding, 2017; Hölttä, 2016).

Constructing fieldwork with participants and digital resources

To correctly approach the question of practice, or the use of things that ‘mold’ activities, understanding and knowledge, I relied on ethnographic methods. In other words, I focused on a real classroom situation, and developed the research questions with the help of the people involved in it, mainly, upper-secondary-school teachers and students.

To begin with, I conducted eight personal, semi-structured interviews with teachers in different parts of southern Finland. This group was selected through a chain referral process in three municipalities in and outside of Helsinki. All teachers were teaching in secondary schools at the time of the interviews. They were of different ages (28 to 60 years-old), had different levels of professional experience, and taught different humanities subjects (three taught language and literature, two history and social sciences, one art, one philosophy and one music). The interviews focused on their practices, perceptions of cultural heritage, and the resources that help them in communicating with their students about the past and cultural phenomena. Later on, I organized a focus group with fifteen teachers in a school that had access to the historical newspapers in question. One of the teachers collaborated more closely in allowing me to observe one of her classes in which 25 pupils aged 16-17 were engaged in a two-week project researching different topics under the theme “Changing newspapers in a changing world” (In Finnish: Muuttuvat lehtitekstit muuttuvassa maailmassa). The classroom observation was organized following collaborative ethnographic activities with the participants (Holmes & Marcus, 2008, p. 84). Here I relied on the teacher, who assumed an important role as my partner in ethnography. She asked her own students about their motivation for choosing their topics, research process, and their opinions about the materials. I analyzed qualitatively fieldnotes and interview transcripts from these activities making use of atlas.ti.

Additionally, two digital resources contributed in revealing more information about the students’ use of materials. At the same time as students were working, I collected the clippings they were doing for their projects, which automatically became available in the public scrapbook collection of the digital library. At a later stage of research, having the students’ accounts, their clippings, and the presentation material from two projects, I decided to investigate further how the digital library of newspapers affected their work process. For doing this, I requested the National Library staff to provide me a list of search expressions, more commonly known as “search logs”.

Finally, to gain more information about the status of digitization and access to historical newspapers, I interviewed two newspaper editors and corresponded with staff from three national libraries (Finland, Germany and Australia).

These research activities were conducted between April 2016 and May 2017 and were facilitated in collaboration with the National Library of Finland. The collaboration was set up in a project that made available newspapers affected by copyright restrictions, that is, published after 1910. Access to these materials was given in 2016/17 to several institutions in a municipality in Eastern Finland.

Newspapers in Finnish schools: a brief history of a lasting relationship

In their respective works Terttu Gröhn (1981), Mari Hankala (2011), and Pirjo-Riita Puro (2014) explore the uses of newspapers in school and their role in the development of media education in Finland. The relationship between the two sectors in Finland was established in the 1960s, through seminars organized for teachers by the newspaper association (Sanomalehtien Liitto), which is an association of publishing companies, distributors, and other stakeholders that still exists today to safeguard the interests of the media industry. The main motivation for introducing newspapers as teaching material was the need for school materials covering two subjects introduced in secondary school after 1964: social studies and economics (Puro, 2014, p. 11). After a period of collaboration with history teachers, who were responsible for social studies, language and art teachers also joined these seminars. As Gröhn reports in her national study of 1978, around 89 percent of school teachers in these four subjects used newspapers in their classes (Gröhn, 1981, pp. 22–23), although she admits that this might reflect too positive an image given that a quarter of schools did not participate in this study (Idem 1981, p. 14).

Each group of teachers reported different preferences about newspapers: articles were used in social studies and language classes, whereas visual material such as comic strips and advertisements were preferred by art teachers. The teachers also had different priorities in terms of focus: the use of language in newspapers interested in language and literature, while reports on government regulations for social studies (Gröhn, 1981, pp. 6–10). The aim of the newspaper association in these early years was to ensure that established subjects allocated time for what was then called mass media education (in Finnish: Joukkotiedotuskasvatus). Another reason for establishing ties with the newspaper community was the lack of consensus on what media education meant. Two things happened to enhance understanding of media education in Finland. First, the newspaper association made it a priority to turn newspapers into everyday working materials in schools. Their plan was initially to teach elementary-school students about the structure and significance of newspapers, and then to generalize their use in secondary education (Puro, 2014, p. 61). Second, schools were given free newspaper subscriptions. According to a study conducted in 1971, 40 percent of schools reported subscribing to a newspaper, and not having enough newspapers was one reason teachers would not use them in the classroom (Gröhn, 1981, pp. 23, 36). In 1981, Erkki Aho from the National Board of Education demanded monthly newspaper subscriptions for schools. By 1983 many schools had a free subscription covering around nine months of the year (Puro, 2014, p. 59).

Today, when the media has diversified and technically evolved since newspapers were prioritized in schools, it is pertinent to ask what is understood under media education. David Buckingham’s definition of media education remains valid, because it focuses on the processes of producing and consuming media rather than on concentrating on one medium:

“Media education, is concerned with teaching and learning about media. This should not be confused with teaching ‘through’ or ‘with’ the media -for example, the use of television or computers as a means of teaching science or history. […] The aim of media education, is not to merely enable children to ‘read’ -make sense of- media text or ‘write’ their own. It has to enable them to reflect systematically in the processes of reading and writing, to understand and to analyse their own experience as readers and writers”. (2003, pp. 4, 141).

Despite Buckingham’s reticence to include teaching through or with media in the concept of media education, in Finland, this is considered under the concept of “educational media” (Kupiainen et al. 2008, p. 6; Vesterinen, 2011, p. 7; Puro, 2014, p. 234). Media literacy, on the other hand, concerns more concrete skills and knowledge about the media, including the various industries involved, messages, audiences and effects (Buckingham, 2003, p. 4; Martens, 2010, p. 3). Since the introduction of newspapers up to the present day, media literacy has been shaped by later mediatic forms such as film, TV, radio, computer games and, finally, the internet. Internationally, newspapers seem to have been given the role of democracy literacy, as studies on younger audiences connect active newspaper reading with civic engagement in practices such as voting, volunteering, and donating (The Newspaper Association of America Foundation, 2007, p. 3).

The following section shows how eight teachers redefined the significance of newspapers in a series of interviews I conducted during the Fall/Winter of 2016 in diverse schools in southern Finland.

Teachers’ practice with newspapers: connecting the class with the real world

Although my initial inquiry concerned historical newspapers, during the interviews I realized that there was very little awareness of the historical press, but the teachers spoke with fondness of current newspapers. In fact, seven of the eight teachers I interviewed could give at least one example of a class activity involving newspapers. In a later focus group with fifteen teachers, some could think of situations in which historical newspapers might be interesting material. During the research process, only one reported using a newspaper archive actively in her class. This motivated me to find out about the similarities and differences of historical and present-day newspapers.

Marja is a language and literature teacher at an upper-secondary school in a town in Eastern Finland. She, like other colleagues, takes advantage of a school subscription to Helsingin Sanomat, the largest newspaper in Finland in terms of circulation. Research shows that after fiction novels, poems and handouts, 75 to 92 percent of language and literature teachers make use of newspapers and magazines (Luukka, 2008, pp. 91–93). In fact, newspapers, along with literature, constitute a more attractive and popular alternative to text-books for Finnish language teachers (Tainio et al. 2012, p. 158). According to previous studies, what motivates language teachers to use newspapers is that they make it possible to use up-to-date texts and renew course content every year (Hankala, 1998, p. 59; Tainio et.al. 2012, p. 158). An example among the teachers I interviewed illustrates this: Maria, an in-training teacher from Helsinki, explains how students in her class wrote critical articles about a recently published novel. The sources they used included excerpts from the novel, a recent newspaper review, and the author’s response to this review on his public Facebook profile.

Although much emphasis is placed on the role of these materials in language education, in Finnish schools, language teachers are not the only users of newspapers. Hanna, teaching government studies, asks students to read and compare news reports in local and national newspapers of “the most important topics of the week, for example if some big decisions in health care have been made during that week, we try to open the difficult concepts”. In her media classes, Pirkko asks her students to collect advertisements from any newspapers at home, and to identify their targets and how they sell products. A teacher of religion discussing Islam with his students, brought to class a recent article about the debate the building of a new mosque had generated. He added:

“I feel obliged that if something important has happened related to the courses I am doing I try to bring it up (…) at high-school level, that is one of the main things teachers should be doing”.

This feeling of obligation sums up the motivation that is implicit in the activities teachers initiate with newspapers, in other words a wish to establish a connection between the classroom and the students’ world.

Figure 1 News on topical phenomena used by teachers in class (from left) “Bullying moves from the school yard to the net –now bullies follow home”, “Algeria raises the world’s largest mosque –‘Shield against radicalisms’. Source: Helsingin Sanomat

In the interviews the teachers described how, when they read newspapers at home, they thought of ways in which they could use them in class. As they talked about this, some described their collecting habits: always having scissors to hand when reading the newspaper, searching online for links to articles they had read previously, or saving articles as PDF files on their personal computers. These collecting habits also explain the popularity of newspapers among teachers: even if they are reading the newspaper privately to keep themselves informed, some teachers are simultaneously thinking of ways of using them in their classes: “Of course, this is not very good if I’m trying to relax, and I’m in bed, and then aha, work... but that is what I do” −admits Maria. These habits exemplify what previous studies suggest about media: they are “embedded in pre-existing domestic routines”, and in this context, their use deviates from their intended purpose (Morley, 2002, p. 86; Pink & Leder Mackley, 2013, p. 680).

These few activities were described by teachers during interviews when asked if and how they used newspapers in their classes. Having analyzed the teachers’ accounts, I have extracted the following categories that illustrate the significance in the practice with such materials in the context of school:

- Topical: Since the 1960s, the prime motivation for teachers to use newspapers has been that they handle matters of current interest, and this is still the case.

- Versatile: Not having been created as school material, newspaper content is diverse enough to cover different subjects and kinds of activity.

- Familiar: Newspaper reading is among the domestic habits of teachers and, at times, students.

- Symbolic: Articles and other content are not necessarily subject matter, but newspaper content illustrates phenomena and concepts that teachers wish their students to explore.

The categories above reflect the expectations that any teacher has about newspapers. In the next section I consider how these aspects are reflected in the projects the students undertook using historical newspapers. The students’ activities illustrate how historical newspapers are equally topical, versatile, symbolic and familiar, but in different ways than their younger equivalents.

Students using historical newspapers: a comparison

Other than different levels of awareness about the existence and what comprised the National Library’s digital collections, none of the teachers in the school where I undertook research had previously used these materials for school work. In the following I combine some ideas for these materials the teachers came up with spontaneously in interviews or during the focus group, along with field notes from the two-week class-project I observed. The aim in this section is to establish similarities and differences between teachers’ experiences using contemporary newspapers, and the students’ projects based on historical newspapers.

In a brainstorm activity organized with fifteen teachers, they showed interest in the historical newspapers. The language teachers were particularly speedy in coming up with ideas for using them in their lessons: literature reviews of classical works that their students had read, or more interestingly, learning about the social context of these classics. Helja refers to a case that exemplifies the teachers’ interest in introducing a connection with today’s world:

“[T]hey can compare the text of Minna Canth, if she is writing about child labor or the status of women. Then I have some text where they can compare how it is today, and how people write about it today”.

Marja had consulted historical newspapers visiting the National Library during her university studies. She was also used to collecting articles for her classes, and decided to include these historical materials in her next cultural literacy and writing course (in Finnish: Kulttuurinen lukutaito ja kirjoittaminen). This course ran over a nine-week period in which the students developed their reading-comprehension and essay-writing skills within different literary genres. This is usually one of the last compulsory language and literature courses that students take before their matriculation examination. Towards the end of it, the teacher organized a two-week media project during which the students would delve, in groups or individually, into the last-century world of newspapers, a corpus of material restricted by copyright but made available to this school through the digital collections of the National Library of Finland (Karppinen, 2016).

Despite the lack of current events, and their absence in teachers’ everyday routines, topicality, versatility, familiarity and symbolism are all reflected in historical newspapers. In the following, digitized historical newspapers are examined through projects realized by this class of upper-secondary students.

Students’ interests and the topicality of historical newspapers

The class of 25 students that participated in this media project had access to a local and a national newspaper, without restrictions, from the first edition (1916/17) until the present day. The students were free to choose, alone or in groups, from a list of suggested topics, or they could produce their own topic. When she was preparing this course Marja recycled popular themes from previous courses. Her goal was for students to read and reflect on changes in the newspaper, in the news making, or in the image of Finland and Finns portrayed in the media.

The choice of topic, what to focus on, and the form of presentation was for the students to decide. This is what Marja referred to as “co-creating a course with students”. This tends to happen when teachers do not hand-pick the materials used in class, or when students decide the format of the outcome. Most groups investigated topics suggested by the teacher. Among the twelve projects, five examined advertisements in newspapers, three looked at how newspapers reported on tragedies, two groups chose wartime propaganda, and the last two groups pursued their own topic: “Cosmetics from 1920 until today” and “Celebrities from 1950 until today”.

To avoid possible restraint among students in front of a stranger, it was Marja who asked some questions after each group had presented their topic. What was the motivation for choosing the topic? What were their search methods? What was one thing they found good or bad about the digital library? Their motivations reveal how these students explored their personal interests via these materials. Two girls thought at first that they would research one of the subjects their teacher suggested, the representation of women in the media. They eventually decided to pursue their shared interest in make-up and explored the history of the cosmetics industry, thus producing their own topic.

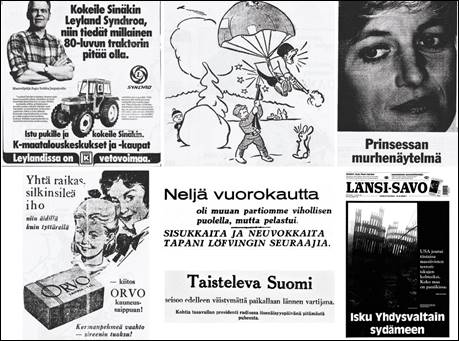

Figure 2 Clippings collected by students (from top left): advertisement for farming equipment, Maaseudun Tulevaisuus, 1980; propaganda cartoon, Maaseudun Tulevauisuus, 1940; Diana Spencer, Länsi-Savo, 1998; Soap advertisement, Länsi-Savo, 1951; War headlines, Maaseudun Tulevaisuus, 1942; WTC terrorist attack, Länsi-Savo, 2001.

Figure 3 Clippings from project “Beauty and cosmetics from 1920 until today” (from left): Tax on perfume and other “beauty products” (1920), Feminine. Face lightening (1962), Sales of cosmetics grow when the economy goes downhill (2011). Photos: Länsi-Savo.

The topicality of these historical newspapers is certainly not evident in the content per se, but can be observed in the connections the students made spontaneously with their own interests. The point about using historical newspapers to explore a concept or a phenomenon in which the students were interested is that they could explore its historical background.

Versatile materials establishing interdisciplinary connections

Until very recently, research about newspaper use in education focused on the content and its relevance to many subjects teachers, from history to the natural sciences (Hankala, 1998, pp. 40–47; Hujanen, 2000, p. 11). Whereas nowadays, there is an interest in phenomena-based teaching, meaning combining subjects and called teemaopinnot in Finnish (Opetushallitus, 2015, p. 220 and ff.). Some teachers mentioned in our interviews that their school favored an interdisciplinary approach to teaching in principle, but did not regularly adopt it. One teacher pointed out that the main reason was because employment contracts are usually connected to a subject, and sometimes to specific lesson hours, which prevents teachers from coordinating classes with colleagues. Collaboration among teachers from different disciplines is the most common approach to teemaopinnot, but as I observed in this project, it is not the only one.

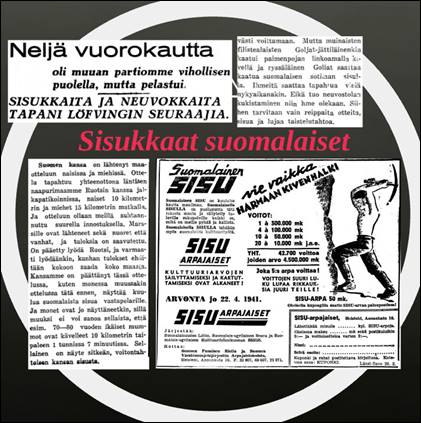

For this and previous projects, Marja encouraged her students to connect their assignments with what they were learning in other classes. This opportunity was seized by two groups of students, one that had learned something about propaganda in a previous history lesson, and one that was interested to see if there was a link between this concept and populism. These groups decided to focus on the propaganda messages that were published in newspapers in wartime. As one student reflected: “I did not know what propaganda was like in the war. And it was surprising to see how much of it there was after all”. This group collected examples of messages that were repeated systematically in newspapers, establishing four categories: the greatness of Finland, Stubborn Finns, a united Finland, and reports about the enemy (In Finnish: Mahtipontinen Suomi, Sisukkaat suomalaiset, Yhtenäinen Suomi, Vihollisesta sanottua). They approached propaganda from the perspective of language use, in line with the objective of this course.

Figure 4 Clippings from project “Propaganda in newspapers in time of war”, illustrating a message conveyed in war-time newspapers: Stubborn Finns (“Sisukkaat suomalaiset”). Photos: Maaseudun Tulevaisuus 1939-1942

Regardless of whether the newspapers are contemporary or historical, their current relevance lies not so much in what they offer to different teacher groups, but in how they allow students to establish connections between subjects themselves.

Remediating familiar things and practices in the digital library

There is something familiar about historical newspapers, and the closer one gets to the present, the more familiar they are. Structural elements of newspapers from 1917 up to the present include a front page introducing the main news, articles distributed in columns, headlines, pictures, thematic sections, and advertisements. From the activities accounted in the interviews, and having seen the popularity of newspapers in school, upper-secondary students do not need to be told what historical newspapers are or how to read them. However, the digital library in which these materials were presented revealed another aspect to their familiarity.

The digital library I refer to here is the digital newspaper collection of the National Library. The concept of digital libraries has been defined more widely as:

“[A]n organized collection of information, a focused collection of digital objects [from books, to manuscripts, photos or sound and video recordings], along with methods for access and retrieval, and for selection, organization and maintenance of the collection” (Witten & Bainbridge, 2003, p. 6).

When students were introduced to this digital library full of historical newspapers they did not require further explanation, even though they had not known it existed. I offered to help them find materials in the first session, but they had no questions and started working with it instantly.

The concept of remediation, meaning how digital technologies reframe older media, could explain this apparent instant familiarity. When Paul Levinson coined this term he was describing how any new medium does not replace previous media, but tackles the inadequacies, such as adding color to black and white photography (Levinson, 1997, pp. 104–105). Updating this concept shortly afterwards, Bolter and Grusin emphasized the reformative nature of new media, and felt that remediation fell short in its meaning at the dawn of digital technology. They understood remediation to include the negative effects of the new media, and that the process of reform was mutual rather than unidirectional from old to new (Bolter & Grusin, 1999, p. 59).

All three aspects of remediation were present in this exercise. A sense of improvement resonates with the way Marja reflected on her experiences 15 years previously with microfilmed newspapers, and on how much easier it was for the students to use the digital library. A negative aspect of the newspapers remediated in the digital library was mentioned by several students researching material published after the 1980s. Even though most newspapers had introduced color by then, the newspapers were digitized in black and white. Finally, having interviewed their teachers, I was aware that these students were actively using internet browsers and news sites for their assignments. They drew from this experience in their approach to older newspapers.

The fact that students are acquainted with newspapers, but also use browsers and news sites, reinforces their familiarity with digitized historical sources such as these newspapers.

Symbolic motivations for using historical newspapers

The aim of the media project was to explore how changes in media text, news making, or the image of Finland and Finns are represented in the media. When she was preparing this course Marja found two aspects of the materials particularly attractive, that turned historical newspapers into symbolic artefacts. First, the digital library is furnished with a search interface, a clipping tool and a personal scrapbook, allowing students very quickly to skim through vast amounts of content, select articles that illustrate their research topic, share clippings among group members, and repurpose them for their own presentations. Second, it was a change from usual sources such as Google and the newspaper to which the school subscribed. In conclusion, the symbolic character the teacher attributed to these materials was that students gained practice in managing and making sense of this ‘mass’ of ‘raw materials’, as she often referred to digital content.

To sum up this comparison between present-day and historical newspapers, one could say that there are similarities to all four aspects of newspapers. Their topicality and versatility, is facilitated mainly by the content of historical newspapers. However, their familiar and symbolic character is attributed by the digital library that contains them. In the following, I examine closer three issues that were raised during this course, in an attempt to establish whether the digital library affected the way students pursued their topics.

Digital libraries: going deep, verbalizing interests, and having free hands

This section discusses the affordances of the digital library. William Gaver describes technology affordances as: “possibilities (with strengths and weaknesses) technology and interfaces offer to the people who use them” (Gaver, 1991, p. 79). In other words, I consider how the digital library enabled and constrained the way the students worked. To facilitate this task, I reviewed comments from the teacher in a follow-up interview evaluating the activity, my field notes containing both descriptions of students’ first working session, and students’ accounts presented orally at the end of the activity. Later, the anonymous logs of the search expressions facilitated by the staff of the National Library provided information about the freedom of students in choosing their research topics .

This exercise was not part of the course evaluation, but it did involve some degree of evaluation. Marja remarked that some projects remained “at a very superficial stage”. A common feature of these projects was that they covered extensive periods of time. By way of contrast, she also mentioned some projects that went “more deep”. One of them focused on a shorter timeframe, as students followed up news reporting on the sinking of a cruise ship in the Baltic in 1994. In addition to describing the event in their analysis, they pointed out characteristic aspects of journalistic text when catastrophes happen: how facts are scarce at the beginning, then there is a turn towards human stories. This group was also praised for having provided a context for each clipping, identifying the date and the source.

According to a previous study comparing how students work with traditional versus digital archives, those using digital archives tend follow a quantitative approach, which could be considered more superficial, focusing on aspects such as change and statistical evidence (Nygren, 2015, pp. 97–98). Similarly, from the twelve projects in Marja’s class, eight consisted in a comparison by decades, the aim being to show change or evolution in how products or people are portrayed by newspapers. Four of these projects went deeper, however, focusing on one concept, product or historical event. The implication here is that the digital nature of the materials alone does not explain this tendency, and that other factors should be considered. The teacher’s formulation of the activity “Changing newspapers in a changing world”, may have inspired some students to attempt to illustrate this change over the years. Moreover, the time dedicated to planning the project was managed differently by different groups, as a result of which some groups may have been able to go deeper than others. At the end of the first working session, some groups had spent more time brainstorming and doing preliminary reading on their topics whereas others had already started inserting clippings in their presentations, and a couple of students used this time to get acquainted with the portal and conducting searches on topics that were not covered in their final projects.

A second notable aspect of the projects was that half of them focused on advertisements. In an attempt to understand this, after the course was over I asked the teacher what she made of it:

“It showed me that they are very much oriented to studying pictures (…) when they choose commercials, and one of them had a nice project about caricatures and propaganda. So, I think it kind of reflects the way young people see the world today, they are drawn to pictures”.

If the students had used print newspapers, one reason for concentrating mainly on images could be that, although journalistic photography only dates back to the 1930s, newspapers have been using illustrations for product and business advertising since the mid-1800s, distinguishing it visually from other content. However, to find content in the digital library the students had to use the search interface that responds to textual queries. Unsurprisingly, during their presentations, all the groups reported using keywords as their main method for finding materials. “Distant reading” is a concept that refers to the need for digital methods enabling researchers to encompass bigger and bigger quantities of literature (Burdick et.al. 2012, p. 39; Moretti, 2000, pp. 56–57). By searching and skimming through lists of results, the students were involved in this form of distant reading, although, to a degree, closer reading of single articles or images was necessary for selecting material. When the students were asked why they chose each subject, some replied that they were interested in a certain product, others mentioned marketing and business, others were vaguer. In conclusion, given the lack of metadata in the image materials and the way the search system is built, the digital library mainly supports a textual approach to the materials, so that students had to verbalize their interest in a few words.

Having considered how these materials challenged students to go deep, and demanded them to verbalize their interest, I turn to one last affordance related to the students’ freedom. The way this activity was organized gave students free hands in using the materials. The only guidelines consisted of a list of suggested topics. They were free to choose another topic entirely, to focus on what they wished, and to present the topic how they liked. The different groups used this freedom differently. Two created their own topics, whereas ten chose topics suggested by the teacher. However, the search logs of the three working sessions, reviewed at a later stage, included concepts that did not appear in the final projects: gender equality (tasa-arvo, naisten asema), nature protection (luonnonsuojelu), and independence (itsenäsyys) among others. This raises the question if the final topics could have been others or more varied. The answer might hint at the raw state of these materials if compared with web browsers and digital news sites. In these, webpages and articles are connected to predefined subject categories. By contrast, other than what is written on the page, digitized historical newspapers have little or no metadata. They lack awareness of contemporary issues and expressions, and the students were not given specific advice on what vocabulary to use.

Recollecting that our practices, understanding and knowledge are ‘molded’ by the things we use, the affordances in this digital library challenged the students’ capacity to go deep, required students to verbalize their research interests and may have limited their freedom to pursue diverse topics. These aspects should be addressed by teachers in some form of guidance when they introduce such materials.

A long way? Historical newspapers and everyday practices in school

The aim in this paper was to find out whether facilitating and fostering the use of historical newspapers in schools would find wider resonance within the school community beyond this isolated case. To this end, I analysed how these materials relate to the existing habits of teachers, or the skills and knowledge that students are supposed to acquire in this stage of education.

Supporting the idea of introducing digital historical newspapers as school material, I showed in the first part of the paper how newspapers are already part of everyday life in schools, and that in terms of the practices they enable, there are many connections between historical and contemporary newspapers. A review of the historical role of newspapers in education, and of how this handful of teachers use them, confirms their strong significance at least in upper-secondary school. Newspapers do not require a role, nor to be specifically tied to a specific subject. The freshness of their content (topicality), the fact that they cover topics relevant to art, language, social issues or philosophy (versatility), illustrate abstract concepts (symbolism), and belong to teachers and students’ everyday lives (familiarity), make newspapers more than an materials for media education or instruments for democracy building (Puro, 2014, p. 232; The Newspaper Association of America Foundation, 2007). However, a reason why these materials are as popular as they are nowadays is the exhaustive work of the Finnish newspaper association since the 1960s, advocating more access to newspapers and developing a common understanding of media education.

The second part of the paper sheds light on the potential contributions historical newspapers and the digital library that contains them can make to upper-secondary education with and about media. Let us consider the specific skills and knowledge to be derived from media literacy. The most remarkable contribution these time machines can offer young students can be summarized in the affordances analyzed in the previous section: exploring the historical background of current phenomena or students’ interests; tracing change across time; requiring students to verbalize their research ideas in a concrete manner; and training their capacity to manage large amounts of digital content by means of distant and close reading. Recognizing, on the other hand, the constraints in the materials and digital libraries (here, lack of image metadata or awareness of historical language) can support teachers in finding a balance between giving guidelines and freedom to their students, and students in delving deeply with the help of these materials. Let us consider, again, Buckingham’s formulation of education about media, which should encourage students to reflect on processes of media production and consumption. It is pertinent to ask how digitized historical newspapers contribute to this concept. The media heritage that, through digitization, is being preserved and progressively made accessible to future generations, could foster in students a sense of awareness of and reflection on processes of media preservation.

The fact that historical newspapers were commonly considered materials to be used exclusively for historical, scholarly research (Gooding, 2017, pp. 62–63) falls short today, as digital libraries are gradually making more and more material available in public online spaces. Digitization and remote access already allow institutions such as national libraries to diversify their audiences by sharing resources with public libraries, or even directly with schools. However, digitization and access might not be enough. The advocacy and mediation carried out by schools, the newspaper association and government officials between 1960-1980, should be considered and possibly imitated before the school community incorporates these materials into their every-day practices.

Still, access remains an important factor, and copyright represents a significant obstacle. According to Finnish law there is a 70-year protective gap during which copyright owners can profit financially from published material (Finland: Copyright Act, 2015 sec. 16a). National libraries, observant of this law, are under pressure to open up their holdings, even though the publishing houses own the copyright, not the libraries (Willems & Grant, 2015, p. 8). However, there have been cases in which newspaper publishers have, under similar copyright laws, allowed free access to materials that would normally still be in copyright. In these cases, national libraries have been the institutions facilitating these materials. This happened in the case of the Canberra Times, which is available in the National Library of Australia’s Trove, and three newspapers from the former GDR available in the Berlin State Library’s ZEFYS. Such initiatives could be emulated in finding a way for schools to discover and introduce these historical documents in their every-day practices.

References

Bolter, J. D., & Grusin, R. A. (1999). Remediation: understanding new media. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Brake, L. (2012). Half Full and Half Empty. Journal of Victorian Culture, 17(2), 222–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/13555502.2012.683149

Buckingham, D. (2003). Media education : literacy, learning, and contemporary culture. Polity Press.

Burdick, A., Drucker, J., Lunenfeld, P., Presner, T., & Schnapp, J. (2012). Digital_Humanities. MIT Press. Retrieved from https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/digitalhumanities

Finland: Copyright Act (404/1961, amendments up to 608/2015) (2015). Retrieved from http://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/details.jsp?id=15992

Friedman, A. M. (2006). World History Teachers’ Use of Digital Primary Sources: The Effect of Training. Theory & Research in Social Education, 34(1), 124–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2006.10473300

Gaver, W. W. (1991). Technology affordances. In 91 Conference on Human Factors in Computing (pp. 79–84). New Orleans, USA: ACM Press. https://doi.org/10.1145/108844.108856

Gooding, P. (2017). Historic Newspapers in the Digital Age: ‘Search All About It!’ Routledge. Retrieved from https://www.routledge.com/Historic-Newspapers-in-the-Digital-Age-Search-All-About-It/Gooding/p/book/9781472463388

Gröhn, T. (1981). Sanomalehtien käyttö peruskoulun yläasteilla ja lukioissa. Kouluhallitus.

Hankala, M. (1998). Sanomalehden monet käyttötavat : kokemuksia yläasteella toteutetuista kokeiluista. Jyväskylä: Koulutuksen tutkimuslaitos.

Hankala, M. (2011). Sanomalehdellä aktiiviseksi kansalaiseksi? : näkökulmia nuorten sanomalehtien lukijuuteen ja koulun sanomalehtiopetukseen. Jyväskylän yliopisto, Jyväskylä. Retrieved from http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-39-4184-0

Holmes, D. R., & Marcus, G. E. (2008). Collaboration Today and the Re-Imagination of the Classic Scene of Fieldwork Encounter. Collaborative Anthropologies, 1(1), 81–101. https://doi.org/10.1353/cla.0.0003

Hölttä, T. (2016). Digitoitujen kulttuuriperintöaineistojen tutkimuskäyttö ja tutkijat (Pro gradu -tutkielma). Tamperen Yliopisto.

Hujanen, E. (2000). Nuoret lukevat sanomalehtiä aikaisempaa vähemmän. Kirjastolehti, (4), 10–11.

Karppinen, P. (2016). The Aviisi project: the golden century of newspapers put to new use (Bulletin). Kansalliskirjasto. Retrieved from http://blogs.helsinki.fi/natlibfi-bulletin/?p=742

Kupiainen, R., Sintonen, S., & Suoranta, J. (2008). Decades of Finnish media education. Finnish Association on Media Education. Tampere University Centre for Media Education (TUCME).

Lévesque, S. (2006). Discovering the Past: Engaging Canadian Students in Digital History. Canadian Social Studies, 40(1).

Levinson, P. (1997). The soft edge : a natural history and future of the information revolution. London: Routledge.

Luukka, M.-R. (2008). Maailma muuttuu – mitä tekee koulu? : äidinkielen ja vieraiden kielten tekstikäytänteet koulussa ja vapaa-ajalla. Jyväskylän yliopisto.

Martens, H. (2010). Evaluating Media Literacy Education: Concepts, Theories and Future Directions. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 2(1). Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jmle/vol2/iss1/1

Moretti, F. (2000). Conjectures on World Literature. New Left Review, (1), 54–68.

Morley, D. (2002). Home Territories: Media, Mobility and Identity. Routledge.

Niemi, H., Toom, A., & Kallioniemi, A. (2012). Miracle of education: the principles and practices of teaching and learning in Finnish Schools. Dordrecht: Springer.

Nygren, T. (2015). Students Writing History Using Traditional and Digital Archives. Human IT, 12(3), 78–116. Retrieved from https://humanit.hb.se/article/view/476

Nygren, T., & Vikström, L. (2013). Treading Old Paths in New Ways: Upper Secondary Students Using a Digital Tool of the Professional Historian. Education Sciences, 3(1), 50–73. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci3010050

Opetushallitus. (2015). Lukion opetussuunnitelman perusteet 2015 : nuorille tarkoitetun lukiokoulutuksen opetussuunnitelman perusteet. Opetushallitus. Retrieved from http://www.oph.fi/download/172124_lukion_opetussuunnitelman_perusteet_2015.pdf

Pink, S., & Leder Mackley, K. (2013). Saturated and situated: expanding the meaning of media in the routines of everyday life. Media, Culture & Society, 35(6), 677–691. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443713491298

Puro, P.-R. (2014). Sanomalehdet koulutiellä : 50 vuotta sanomalehtien ja koulujen yhteistyötä. BoD – Books on Demand.

Reckwitz, A. (2002). Toward a Theory of Social Practices: A Development in Culturalist Theorizing. European Journal of Social Theory, 5(2), 243–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684310222225432

The Newspaper Association of America Foundation. (2007). Youth media DNA. In search of lifelong readers. Virginia, USA: American Press Institute.

Vesterinen, O. (2011, April 29). Media Education in the Finnish School System : A Conceptual Analysis of the Subject Didactic Dimension of Media Education. University of Helsinki, Helsinki. Retrieved from https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/26051

Willems, M., & Grant, F. (2015). Roadmap for Improving Access to Digitised Newspapers. Association of European research libraries (LIBER). Retrieved from http://www.europeana-newspapers.eu/public-materials/deliverables/

Witten, I. H., & Bainbridge, D. (2003). How to build a digital library. San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers.

Author’s vita

I have a degree in audio-visual communication from the University Complutense of Madrid (2006) and a M.A. in media studies from the University of Potsdam (2010). Since 2006, I have worked in a university library, a TV-archive and several museums, in projects dealing with documentation, digitization of collections, and visitor studies. Since 2016 I am undertaking doctoral studies on European ethnology at the University of Helsinki, under the title “Cultural heritage goes to school: redefining sites of memory in the digital age”. This is the first of four articles that comprise my doctoral dissertation.

©2018 (author name/s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Seminar.net - International journal of media, technology and lifelong learning

Vol. 14 – Issue 1 – 2018