Vol 9, No 3 (2025)

https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.6285

Article

Towards good higher education partnerships: A co-constructed model

Elizabeth Agbor Eta

University of Helsinki/AMCHES, University of Johannesburg

Email: elizabeth.eta@helsinki.fi

Meeri Tiensuu

Tampere University

Email: meeri.tiensuu@tuni.fi

Kelly Brito Salas

University of Helsinki

Email: kelly.brito@helsinki.fi

Anaïs Georges

University of Helsinki

Email: anais.georges@helsinki.fi

Hanna Kontio

University of Helsinki

Email: hanna.kontio@helsinki.fi

Elina Lehtomäki

University of Oulu

Email: elina.lehtomaki@oulu.fi

Marika Oikarinen

University of Oulu

Email: marika.oikarinen@oulu.fi

Taimi Nghikembua

University of Namibia

Email: tnghikembua@unam.na

Frieda Nanewo Shingenge

University of Namibia

Email: fshingenge@unam.na

Abstract

This research examines elements of global higher education (HE) partnerships and the roles of dialogue(s) and co-creation in knowledge production aimed at fostering sustainable partnerships. By studying and reflecting on the processes of global South–North HE partnership building, this research sheds light on the complexities and opportunities of developing meaningful relationships. Limited understanding of what constitutes a good partnership and synergy between Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 4 and 17 raises questions about how to foster sustainable partnerships at both local and global levels. This article presents findings from partnership dialogues among academic and administrative staff from African and Finnish universities, all experienced in HE partnerships. The data comprise responses from a questionnaire and a multi-stakeholder workshop addressing what constitutes a good partnership. The findings result in a generic metaphoric model that depicts our view of a partnership as a butterfly comprising two (institutional) wings interconnected by various relationships that enable individuals in HE institutions to engage in dialogue(s), reflect on existing practices, and build more equitable and sustainable collaborations. We conclude that the foundations of solid, transformative HE partnerships are developed through collaboration and co-creation among individuals. This study contributes to international education by demonstrating how dialogue and co-creation within HE partnerships can advance sustainability across global contexts while also fostering critical reflection and scaling up action-oriented, reciprocal institutional transformation.

Keywords: international partnerships, dialogue, knowledge co-creation, higher education, interconnectedness

Introduction

This study explores higher education (HE) partnerships through a series of dialogues among scholars and educators with experience in Global South–Global North partnerships. The aim was to explore the participants’ views of what constitutes a good partnership. We argue that such dialogues and co-creative practices support the building of more equitable global partnerships, which are key to advancing all UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In this study, the concept of sustainability refers both to the long-term building of higher education institution (HEI) partnerships and to their contribution to the SDGs through education. This dual perspective reflects the synergy between SDG4 and SDG17. While SDG4 promotes inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning, SDG17 focuses on global partnerships in sharing expertise, resources, knowledge, and technology. We argue that the role of HEIs as actors promoting, building, and educating for sustainable futures through international partnerships highlights the opportunities to advance SDG4 and SDG17 together.

Analyses of HEIs’ reports on SDGs show little interaction between SDG4 and SDG17 (United Nations, 2019; 2024). Furthermore, Bexell (2024) notes weak advocacy for sub-indicators of global and cross-sectoral partnerships. The 2024 SDG Report also notes insufficient data for these, particularly SDG4.7 on sustainable development education (United Nations, 2024). It calls for whole-of-society partnerships in data collection and monitoring. This raises a key question: How can HEIs contribute to strengthening partnerships that support both sustainable development and sustainable education?

In this study, we approach the key question of partnerships for sustainable development from the perspective of people who have participated in Finnish and African HEI collaboration activities. We explore the perceptions, understandings, and experiences of and about partnerships through partners’ dialogues and how such dialogues foster equitable partnerships through the following research questions:

1. What elements constitute a good partnership?

2. How can these elements be developed and sustained?

This study contributes to the ongoing discussion on global HE partnerships to deepen the understanding of the role of dialogue and co-creation in fostering equitable partnerships corroborating the dialogical approach to knowledge production (Marková, 2016). Although efforts to create, develop and sustain HE partnerships are generally supported, research on these forms of collaborations are dispersed and diverse, making it difficult to draw conclusions in contexts where methods and approaches differ significantly.

Actions within global HE partnerships include collaborative degrees, student and staff mobility, research collaboration, joint teaching and education programmes, capacity building and the formation of HE networks (Hanada, 2021; Lanford, 2021; Woldegiorgis & Scherer, 2019). Such partnership activities are often viewed as mechanisms for knowledge exchange and innovation, aligning with SDG4. Simultaneously, they exemplify the principles of SDG17 through international collaborations that enhance educational opportunities and strengthen instructions, ways of working and practices in different contexts. They also foster relationships (Lanford, 2020) not only between institutions but also between countries and companies, reflecting SDG17’s call to strengthen implementation and promote sustainable global partnerships.

While the arrangements, motives, and forms of global HE partnerships vary, they share some commonalities, including transnational participation by individuals and institutions (Lanford, 2021). These partnerships are underpinned by a commitment, whether formalised through agreements or maintained informally, to achieve a specific set of objectives, ideally mutually agreed upon and beneficial (Lanford, 2021; Woldegiorgis & Scherer, 2019). Therefore, it is crucial to continuously examine emerging trends and case studies across contexts to better understand and enhance the dynamics and sustainability of HE partnerships (Woldegiorgis & Scherer, 2019). Here, sustainability refers to maintaining partnerships and activities.

One of the main challenges of HE partnerships between African and European HEIs is maintaining relationships amid varying funding systems and changing circumstances (Woldegiorgis & Scherer, 2019). Furthermore, partnerships often face socio–political turbulence, which can challenge the realisation of common goals. In other words, while HEIs seek innovative solutions to global challenges through their partnerships, their efforts are constrained by national frameworks, including funding, governance, and strategic priorities.

Additionally, stakeholder salience – the perceived influence of actors based on power, legitimacy and urgency (Mitchell et al., 1997) – is increasingly relevant to HE, particularly in discussions of collaborative governance and partnership dynamics (Al-Hazaima et al., 2025; de Groot et al., 2025; Filho et al., 2025; ; Mäkinen, 2022; Shenderova, 2023). Although traditionally applied in linguistics and stakeholder theory, salience offers a valuable lens for understanding power and urgency asymmetries in HEI collaborations. Even when participants hold similar formal roles or titles, disparities in perceived salience can distort knowledge production and reinforce global inequalities (Bender, 2022; Eta et al., 2024). These challenges are amplified in South–North partnerships, where asymmetric access to resources further complicates sustainability. Addressing these asymmetries requires attention to at least four aspects critical to partnerships: reciprocity (Hoekstra et al., 2018; Yarmoshuk et al., 2019), equity (Unterhalter & Howell, 2021), mutual interests (Mitchell et al., 2020) and epistemic decoloniality (Asare et al., 2020; Teferra, 2016). Reciprocity involves ensuring benefits for all partners where Global South partners’ needs may require prioritisation (Yarmoshuk et al., 2019). Historically, patterns of leadership and authorship have undervalued sub-Saharan African partners (Teferra, 2016) and their knowledge systems. Issues of data rights highlight the need for equitable cooperation. HEIs must actively address reciprocity in internationalisation strategies and critically examine how knowledge is produced (Keahey, 2020).

Equity in South–North partnerships require addressing power imbalances that hinder contextually relevant knowledge for social impact (Unterhalter & Howell, 2021). Many collaborations remain unequal as global North institutions often set agendas, shaping priorities, authorship, and epistemic dominance (Mitchell et al., 2020). These dynamics reflect stakeholder salience, which often privileges Northern institutions in decision-making processes. Colonial legacies persist through extractive practices, funding disparities, and ethical concerns such as ‘helicopter research’ and ‘ethical dumping’ (Haelewaters et al., 2021; Schroeder et al., 2018;), reinforcing asymmetries in salience and marginalising Southern voices.

HEIs in sub-Saharan Africa are addressing epistemic challenges through pluralistic approaches (Seehawer & Breidlid, 2021), urging Global North researchers to embrace diverse knowledge systems (Kontinen et al., 2015; Woldegiorgis, 2021) and dismantle neocolonial/postcolonial inferiorities and hierarchies. Ethical dilemmas in HE partnerships stem from the epistemological assumption that knowledge is primarily generated in the Global North, sidelining Southern contributions and limiting critical reflections on prejudice and colonial mindsets. This imbalance is reinforced by neoliberal approaches that commodify education (Eta, 2023), shaping salience through market-driven metrics of legitimacy and urgency. The persistent emphasis on gaps in African contexts similarly overlooks locally generated, context-specific knowledge (Ulmer & Wydra, 2020), reducing opportunities for Southern actors and epistemologies. To counter these trends, initiatives such as the Africa Charter for Transformative Research Collaborations aim to recalibrate salience by recognising the legitimacy and urgency of South-led knowledge productions, shifting from disparity towards equitable, systemic change (Aboderin, 2024). However, HE collaborations often oversimplify complex realities and neglect ethics and sustainability (Urenje et al., 2017). Reframing global HE partnerships as spaces for co-creation can foster sustainability transformations by integrating diverse epistemologies (Linnér & Wibeck, 2019; Redman & Wiek, 2021). Examining dialogue and co-creation in such partnerships can help renegotiate saliences through mutual recognition, shared legitimacy and context-driven urgency.

Research context

The research context for this study is HE partnerships between Finnish and African HEIs. Finland has created various global HEI networks and programmes, and universities have developed ethical guidelines for responsible academic partnerships with the Global South (Brito Salas & Avento, 2023). Aligned with Finnish research integrity guidelines (Finnish National Board on Research Integrity, 2023), these guidelines represent a self-reflective effort to promote equity and responsible HE partnerships. Similar efforts have taken place in African contexts, where national and international funding institutions have focused on enhancing the quality of HE (Woldegiorgis & Scherer, 2019). The trend of participating in global partnerships and internationalising HEIs has gained momentum in Africa during the 21st century, guided by various regional and national policy documents (Lebeau & Oanda, 2020).

The historical relationship between Africa and Finland in research, science, technology, and innovation has developed mainly through collaborative development initiatives, educational partnerships, and technological cooperation (Kagiri-Kalanzi & Avento, 2018). Finland has been involved in the development of various African countries since the 1960s, focusing on capacity building in sectors such as health, agriculture and sustainable development. Finnish HEIs have forged research collaborations with African partners, particularly in environmental science, ICT, education, and public health. While the relationships continue to evolve, they are grounded in a shared commitment to advancing scientific knowledge and collaboratively addressing global challenges.

Partnerships are often framed as vehicles for capacity building, quality improvement, broadening participation and governance. Yet, they can also be marked by tensions and competing agendas (Kassie & Angervall, 2022; Luthuli et al., 2024). Despite policy calls to shift from equality to equity, unrecognised behaviour, attitudes, and belief systems perpetuate power imbalances in everyday interactions (Luthuli et al., 2024) and, in doing so, directly affect stakeholders’ salience. For instance, an Ethiopian–Norwegian university partnership highlighted contradictions: Partners sought mutuality while avoiding dependence and struggled to balance local needs with global expectations amid resource constraints on the Southern side (Kassie & Angervall, 2022). In this study, we explore partnerships from the perspective of academic and administrative staff involved in HE collaboration activities and the role of dialogue and co-creation in partnership development.

Enhancing partnerships through co-creation, knowledge communities, and dialogues

We draw on the concepts of knowledge co-creation, knowledge communities, and transformation to explore perceptions of good partnerships based on dialogues between HE actors in the global South and North. In line with the social–constructivist perspective, which views knowledge as socially constructed (Guterman, 2006), we recognise that collaboration and participation in cultural practices drive knowledge development (Paavola et al., 2004; Rolin, 2015). Co-creation occurs when a group collaboratively develops shared objects (in our case, perceptions of good partnerships) to develop its practices (Paavola et al., 2004). To better understand the complexities and transformative potential of HE partnerships, it is necessary to engage academic and administrative staff from participating HEIs, as well as possible external stakeholders, in co-creating shared knowledge based on their experiences and values. This approach offers insights into how North–South HE partnerships can operate in practice to be mutually beneficial, sustainable, and transformative.

In this study, co-creation is not only a method of producing knowledge but also a transformative process driven by collaboration, engagement, and inclusivity. It fosters shared understanding, mutual respect, and collective benefit through participatory, bottom-up and transparent practices (Linnér & Wibeck, 2019; Mitchell et al., 1997). More than just bringing people together, co-creation facilitates co-learning and helps diminish hierarchical structures between actors (Bell & Pahl, 2018). Similarly, Rolin (2015) highlights that scientific knowledge emerging from collaborative practices relies on collective beliefs, trust, and interactions among partners. This ensures that the knowledge created reflects the collective perspective rather than being limited to individual viewpoints, reinforcing the need for trust within the team.

For us, co-creation constituted a knowledge community in which data were both created and analysed. The diverse perspectives within this spontaneous, inclusive space have contributed to challenging hegemonic (Northern) epistemologies in knowledge production, supporting the incremental transformation of HE. Building on Connell’s (2007, p. 213) argument that knowledge should connect across global peripheries, our approach of data gathering, analysis and co-writing was a co-creative process, bridging perceptions, understandings, and epistemic perspectives. Co-creation in this project meant working across and along differences, embracing diversity in ways that Tsing (2015, p. 27) describes as ‘contamination’: ‘the idea that encounters shape and changes us, making space for new ideas, directions, and possibilities.

Tsing’s concept of contamination informs our understanding of dialogue as a transformation practice. In a positive sense, contamination highlights how encounters with diverse perspectives enrich our understanding and open new directions. Applied to dialogue, this process enables the exploration of differing epistemologies within interactions (Marková, 2016). Building on Marková’s (2006) view of dialogue as shaped by the socio–historical context, we argue that dialogue occurs not only among individuals but also between their ideas, perceptions, and contexts, aligning with theories of social knowledge. Tensions within dialogues arising from the interplay between the self and others or between established and emerging knowledge are essential for sustaining the flow of ideas.

In this study of HE partnerships between Finnish and African HEIs, dialogue plays a significant role in shaping evolving perceptions of ‘good partnerships’. Through the continuous exchange of viewpoints, knowledge and experiences, researchers–practitioners can co-create understanding, respect and meaningful transformations.

Materials and methods: Dialogic research approach

This study applies a dialogic research approach that incorporates diverse perspectives and salience (power and influence), addressing similarities and differences in experiences to foster understanding and professional learning for change (Hofmann, 2020a). It also enables new theorising informed by participants’ insights (Hofmann, 2020b). In this study, we engaged in three dialogue spaces: a survey, a multistakeholder event with various stakeholders and internal author dialogues. While the external dialogues – among academic and administrative staff from both Finnish and African HEIs – centred on co-constructing knowledge through qualitative data collection and a stakeholder dialogue event, these dialogues were complemented by ongoing reflective, critical conversations among the authors of this paper throughout planning, data collection, analysis and multiple revisions for four years.

The dialogues took place within two HE networks, namely the Finnish University Partnership for International Development (UniPID) and the Global Innovation Network for Teaching and Learning (GINTL), which foster collaboration between Finnish HEIs and their Global South partners. UniPID is a national platform that promotes global responsibility and sustainable development by supporting interdisciplinary teaching, research, education, and partnerships, providing services such as virtual courses, research cooperation support, and policy dialogue. GINTL is a national initiative that enhances global academic partnerships in education and related fields to foster an equitable and sustainable collaboration. It brings together researchers, educators, students and practitioners for mutual learning, knowledge co-creation and capacity development. Both networks not only support existing collaborations but also facilitate new partnerships between individuals and institutions.

The nine-member author team represents a diverse range of institutional, cultural, and regional perspectives from Africa, Europe, and Latin America. This diversity surpasses geography, including differences in (disciplinary) backgrounds, career stages, and professional roles. The team includes members from Finnish universities, an African partner university and the two networks mentioned above. The varying roles and positions shape how we engage and experience salience, agency, and knowledge production in partnership dynamics. With extensive experience with global development, HE and international collaboration, the team’s engagement with positionality and reflexivity has been central to analysing what constitutes good partnership.

The coordination teams of UniPID and GINTL collected research material from 2021–2022 through various initiatives. They invited and funded academic staff from partner African[1] HEIs to engage in a critical dialogue on good partnerships in Finland. They developed a qualitative questionnaire with four open-ended questions. Distributed through existing networks, they gathered insights from individuals in Finnish and African HEIs, with 20 responses from 17 Finnish institutions and nine African countries – 16 from African academic and administrative staff. These responses shaped the second part of the project, an online stakeholder dialogue event centred on the question, ‘What are the characteristics of good partnerships?’

The stakeholder event took place in spring 2022, bringing together about 40 participants from 37 Finnish institutions and nine African countries, including NGOs and embassies. Participants were research, teaching and administrative staff involved in Finnish HE pilot networks and their partners in Africa. The event focused on current challenges, priorities, and elements of good Finland–Africa partnerships. To prepare, we analysed questionnaire responses and identified 13 key ingredients of good partnerships, represented as sticky notes on visual maps (i.e. Miro boards). These included trust, mutual respect, mutual understanding, openness, transparency, flexibility, mutual benefit, a common vision, inclusion, accountability, collaboration, communication, and joint decision making.

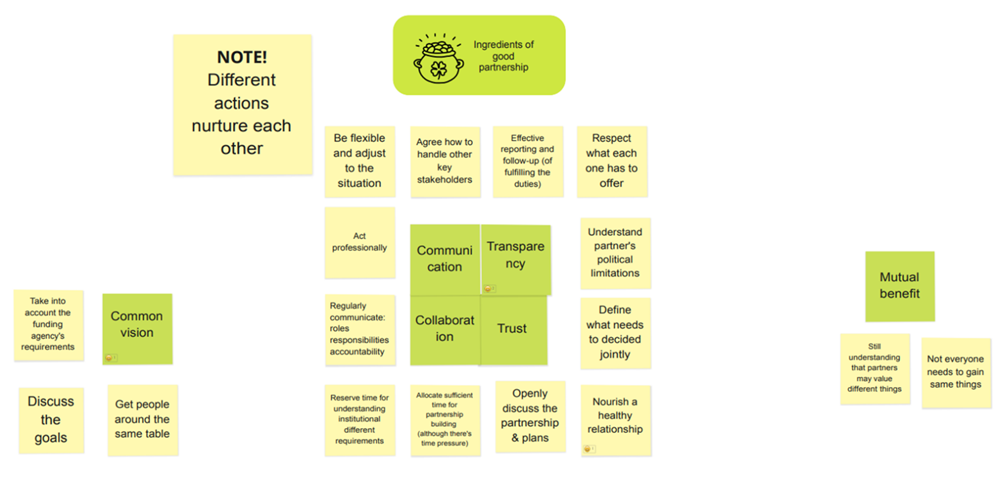

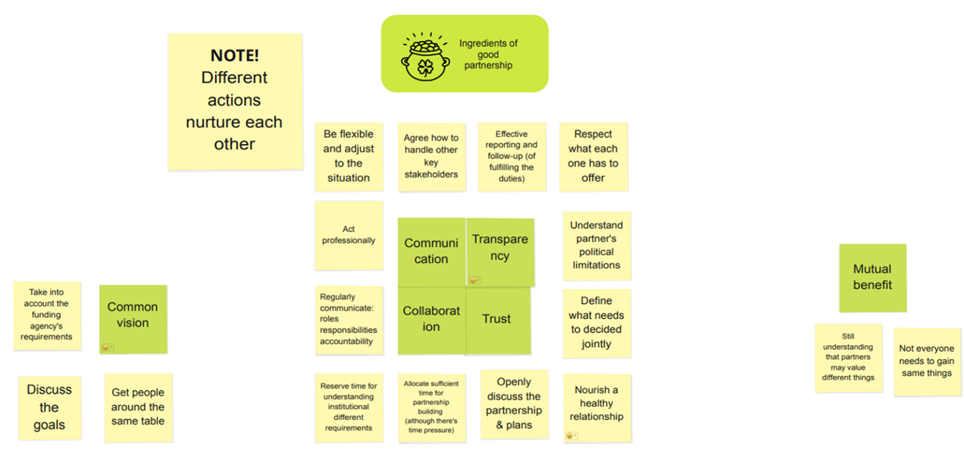

During the event, participants were divided into six mixed groups of African and Finnish HEI representatives. Each group worked on a similar Miro board, refining the proposed ingredients of good partnership, adding new ones, and selecting the top three. They then suggested concrete actions to implement these elements and used emojis to highlight the most significant takeaways (see figures 1 and 2 for examples).

Figure 1. Data Example 1. Collectively created Miro board

Figure 2. Data Example 2. Collectively created Miro board

The primary data for this article comprise the six Miro boards produced during the stakeholder dialogue event. Since the exercise aimed to capture collective insights and foster dialogue rather than individual perspectives or demographic factors, no personal participant data were collected. This way, the focus remained on shared understandings and co-creating knowledge instead of individual identities and affiliations.

We applied reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; 2022), which acknowledges the researcher’s subjectivity as a valuable resource for the development of insightful and unique analytical processes and outcomes (Braun & Clarke, 2022). In this approach, themes do not passively emerge from the data but result from the researcher’s subjective interpretation. Therefore, it is essential for the researcher to be transparent about their positionality, choices, and biases. Given that participants did not provide detailed definitions of the elements they wrote on the Miro boards, our analysis required interpreting their intended meanings.

Following Braun and Clarke’s (2006; 2022) six-step process, we started by familiarising ourselves with the data, engaging with them several times for different perspectives, examining all the data and focusing on specific boards, questions, or recurring ideas. Subsequently, we examined how individual groups engaged with the tasks, noting recurrent ideas and the additional elements they contributed. Using an inductive approach, we identified eight codes reflecting key elements of good partnerships: planning and clarity, time management, funding, flexibility, knowing the partner and their context, valuing the partner’s views and expertise, communication, and relationships with external stakeholders. From the codes, we developed two overarching categories: organisational elements and relational aspects of partnerships. These two categories formed the ‘candidate themes’ (Braun & Clarke, 2022), which were further reviewed against the original data to ensure coherent semantic and latent meanings. Through further discussion and critical reflection, we refined the themes into (1) the relational dimension of partnership and (2) the organisational dimension of partnership.

This study, which evolved through a series of three dialogues, also requires ethical reflection. Such considerations extend beyond co-creation and participant involvement in the stakeholder dialogue event to include the methodological choices of the team. Data were gathered from a limited number of participants from Finnish HEIs and their partners in African countries whose experiences and backgrounds were not mapped in detail. Hence, the analysis focused on the Miro boards and the recurring themes identified from them. The authors’ discussions also significantly informed the findings. As the research team members represent different positions, levels of seniority and active engagements in these partnership dialogues, the analysis was influenced by our perceptions and work contexts. However, the dialogic research approach enabled us to surface varying degrees of salience among participants and ourselves, defined in this context as the perceived legitimacy, power, and urgency of their and our voices within partnership dialogues (Mitchell et al., 1997). This dimension shaped how participants and we engaged in the co-creation process and how we and their perceptions influenced the emerging themes. Hence, the models and metaphors presented in the findings were developed through a collaborative analytical process to provide starting points for reflection and action for sustainability transformation in HE.

Although the study was co-creative, we should also acknowledge the various interests and intentions that became known during the process, in other words, ‘the unseen politics of co-production’ (Harman, 2019, p. 104). What remains unseen, unquestioned, and unanalysed are the interactions and motives of those involved in the dialogue process. The interdisciplinary team came together specifically for this article, bringing contexts, perceptions and experiences fostering sustainability transformation in HE collaborations. This process created a learning ecosystem (Crosling et al., 2014) focused on the elements of good HE partnerships. Although internal dynamics were not the focus, they unavoidably affected the work. The study’s theme and the chosen methods also encouraged reflection within the team concerning what constitutes good partnerships.

Given the uniqueness of each partnership, people engage in them from distinct positions with their own expectations. Fostering open discussion about these differences is key to seeking common ground and advancing meaningful partnerships. It is important to understand positionalities in the field and to recognise how they influence experiences, perceptions, preferences, and actions. Beyond geopolitical diversity, professional roles ranging from research to programme-oriented roles also shaped approaches to partnership building. These starting points and resources influence conversations about partnerships. Hence, certain elements may receive more attention and emphasis in specific contexts than in others.

Results: Elements of good partnership

Participants’ diverse understandings of partnerships informed the various dimensions characterising good partnerships. Regarding the first research question – what constitutes a good partnership? – Table 1 summarises and categorises eight dimensions. Elaboration on each dimension is provided in the subsequent section. The latter part proposes a metaphorical model of good partnerships. This model responds to the second research question concerning how these elements of good partnerships can be developed and sustained and, in doing so, transform current understandings of HEI collaborations.

Table 1. Interconnected dimensions of good partnerships

|

Organizational dimension |

Relational dimension |

|||||||

|

Planning and clarity through common visions, agreeing on roles and responsibilities |

Managing time, balance between immediate actions and long-term commitment |

Funding management, ensuring adequate resources and addressing inequalities |

Flexibility, openness and adapting to changing situations |

Knowing and understanding the partner and each other’s contexts |

Valuing the partner’s views and expertise, Valuing the input and skills of different types of actors |

Open and regular communication, both formal and informal |

Agreeing on how to work with external stakeholders |

|

Table 1 lists the dimensions of good partnerships, categorised as organisational and relational. The organisational dimension encompasses structural and managerial elements, whereas the relational dimension refers to how collaborators interact or engage. These two dimensions do not operate in isolation; they are interconnected and collectively contribute to establishing good partnerships.

Organisational dimension

Planning and clarity through common visions, agreeing on roles and responsibilities

All six groups emphasised the importance of collaborative planning from the outset of the partnership, establishing a clear and shared vision encompassing all its aspects. Groups 1, 4 and 6 emphasised the need to identify their objectives. Group 1 highlighted the significance of defining specific aims for each partner, whereas groups 5 and 6 underscored the need for each partner to agree on roles and responsibilities. Group 6 also suggested that decisions should be made collectively on matters that require joint agreement but not necessarily in all cases, provided that the partners had mutually agreed upon them.

Managing time

Almost all the groups mentioned the issue of time management. Group 4 highlighted the importance of open communication and ensuring a shared understanding of time among the partners. Several groups also emphasised the need to allocate sufficient time for various partnership processes to unfold. For example, Group 1 identified trust as an overarching ingredient of a good partnership that required time to build. Group 4 emphasised the importance of allowing time for reflection, and Group 6 highlighted the need to dedicate ample time to partnership building, even under time constraints. Groups 4 and 6 also pointed out the necessity of allocating sufficient time to address practical matters and understand institutional requirements.

In addition, several groups underscored the importance of fostering long-lasting and impactful partnerships. Group 3 highlighted continuity, sustainability, and long-term planning as essential to a good partnership. Group 5 viewed partnerships as long-term investments, suggesting that good partnerships should have a long-term impact. Group 4 identified long-term commitment as a critical ingredient, implying that commitment to the partnership should be embedded in its institutional structure, with skills and knowledge transfer requiring long-term commitment.

The groups also stressed the need to delimit and respect time constraints. Group 4 highlighted the importance of starting the collaboration on time and establishing agreed-upon deadlines. Group 5 identified a sense of urgency as crucial for good partnerships, recommending the provision of conditions that are conducive to facilitating efficient work and generating rapid results.

Funding management

Several groups brought attention to funding in terms of both planning and time. Considering the importance of durability and sustainability, groups 3 and 4 stressed the necessity of careful budgeting to secure sufficient financial resources covering all stages of the partnership. Group 6 also emphasised the need to consider the funding agency’s requirements during the planning process. Group 1 further pointed out the necessity of addressing the issue of North–South inequalities in funding instruments that greatly affect partnerships and joint decision making.

Flexibility

Being flexible and able to adjust when necessary were also characteristics that several groups highlighted. Group 4 noted that partners should remember to allocate time to uncertainties. This seems to relate to the concept of flexibility as written down by groups 3 and 6, both of which emphasised the need to allow space for changes and to remain open to taking new directions in the partnership. Both groups also stressed the importance of adaptation in partnership building.

Relational dimension

Knowing and understanding one’s partner and each other’s contexts

Most groups underscored the importance of understanding prospective partners and their respective contexts. Groups 1, 5 and 6 stressed the need to learn about partners’ interests, needs and challenges to build good relationships. Group 6 pointed out that partners should recognise and value potential differences in perspectives. Group 2, in turn, suggested that technology alone was not sufficient to foster partnerships and that partners should become acquainted through alternative means. Group 5 referred to the importance of visiting overseas partners to gain a first-hand understanding of their respective countries and contexts. Group 2 also recommended building personal connections between partners.

According to the groups, it is crucial for partners to understand each other’s institutional contexts. Groups 2, 3 and 6 pointed out that familiarisation among partners was an integral step in understanding their context. Group 2 also stressed the need to become acquainted with the partner institution. Group 6 suggested dedicating time to understanding institutional requirements, and Group 3 mentioned the necessity of understanding bureaucratic processes, including visa-related requirements.

Moreover, Group 4 referred to the importance of understanding each other’s backgrounds and local contexts. Being able to understand the partner country’s capacity and infrastructure was mentioned by Group 5, whereas Group 6 specified the need to understand political limitations. Group 5 further indicated the importance of cultural understanding and suggested involving individuals who were familiar with both partner countries. Listening to the partner to gain a deeper understanding was also emphasised by Group 4. Group 2, in turn, focused their reflection on building a healthy relationship with the partner and mentioned the competences required to achieve this, such as intercultural competence, patience and tolerance. Uniquely, this board highlighted the need to develop the relevant skills to make partnerships effective. Further reflection on the skills required to enable partnership development would be beneficial.

Valuing partners’ views and expertise

Most groups agreed that valuing partners’ unique views and expertise was essential for fostering good partnerships. Groups 1 and 6 emphasised the importance of respecting each other’s perspectives and valuing what each partner contributed to the collaboration. In addition, groups 3 and 5 suggested incorporating input from various actors to enhance the partnership: Group 3 recommended including actors from various levels, such as students, faculty members, and leadership, whereas Group 5 advocated leveraging the specific skills of individual actors, including alumni.

Open and regular communication

All six groups recognised and highlighted the crucial role of communication in partnerships in facilitating the realisation of the other essential elements mentioned above. The need for open and regular communication throughout the partnership process was emphasised, including planning, becoming acquainted, sharing views and expertise, and agreeing on practical matters. Group 3 further stressed the importance of establishing agreed-upon methods of communication encompassing both formal and informal channels, and Group 5 suggested that all partners should be actively involved in communication.

Agreeing on how to work with external stakeholders

Several groups highlighted the need to consider the role of external stakeholders and maintain meaningful communication with them. Group 6 suggested that partners should collectively determine how to engage with key stakeholders, for example whereas Group 1 pointed out the importance of goodwill and governmental support, emphasising the need for effective communication between partner countries at the government level through embassies. Group 1 further remarked that government involvement could significantly affect the availability of resources and funding for partnerships, the prioritisation of goals and partners’ capacity for action.

Towards developing and sustaining good partnerships ─ butterfly model

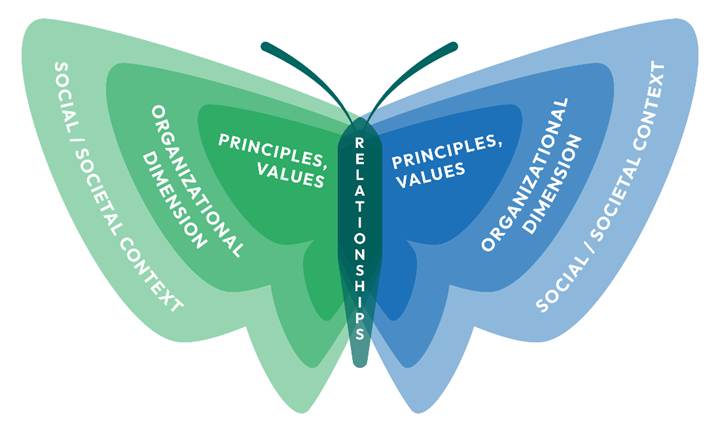

Having reflected on the analytical process and related discussions, we propose a metaphorical model for developing and sustaining good South–North HE partnerships (Figure 3). Metaphors extend beyond language; they are the process of understanding and experiencing one concept in terms of another (Temmerman, 2021). Thus, a metaphorical model enables us to grasp new facts, situations, or processes by drawing on analogies with what we already understand. Through this reasoning, unfamiliar concepts become more accessible and meaningful (Temmerman, 2021).

The partnership is depicted as a maturing, developing butterfly with two institutional wings connected by various relationships. The beautiful symmetry of the butterfly visualises the often ideal and even naive expectations of what partnerships should be like, while its fragility highlights the need for care and sensitivity to changing conditions. Similar to a creature transforming from an egg to a caterpillar, chrysalis and finally an adult, the metaphor illustrates the multiple stages of partnership building, during which developmental milestones must be reached before healthy relationships can emerge. Yet, it is quite common for the process of transformation to include unexpected and complex events that leave an imprint on the development of the partnership.

Figure 3. Formation of good South–North partnerships in higher education: The butterfly model

Using the butterfly metaphor, the model highlights the convergence of two entities – each represented by the butterfly’s wings – illustrating how diverse educational institutions (aligned with SDG4) and their partners (aligned with SDG17) can collaborate effectively. Similar to partnerships, butterflies are unique living creatures that experience various kinds of growth and pains along the way that may threaten their development if not addressed. They evolve in specific contexts and at particular times. The two wings symbolise partnering institutions, each rooted in social and organisational contexts, guided by strategies and organisational ways of working, values and principles essential for partnership formation. The interconnected parts of the wings represent the elements needed for the butterfly to fly. The interconnected relationships forming the body of the butterfly symbolise not only collaboration, but also the dynamic negotiation of salience. Just as the wings must balance to enable flight, partnerships must recognise and adjust to asymmetries in power, legitimacy, and urgency. Partnerships, similar to butterflies, may lack perfect balance, making flight challenging. Butterflies are inherently vulnerable, just as partnerships are susceptible to various obstacles and environmental changes. Thus, the partnership can only thrive when conditions (institutional frameworks etc.) are conducive; otherwise, its development will become problematic and delayed, or it will eventually cease to exist.

The butterfly’s transformation from an egg to a caterpillar chrysalis and, finally, an adult also reflects the stages of partnership development. Discussions about successful partnerships often tend to focus on tangible outputs such as funded projects, memoranda of understanding, publications, and numbers of beneficiaries. However, local-level transformations and concealed processes often remain invisible, rather similar to the unseen stages of metamorphosis. Not all eggs or caterpillars reach adulthood, symbolising the fragility, complexities, limitations, and frames inherent in partnership development.

We recognise the challenges of creating a model or framework that reflects the diverse realities, contexts, and understandings of partnerships. Our butterfly model aims to foster robust partnerships that advance SDG4 and SDG17 by suggesting relevant elements while emphasising the need for context-specific negotiations and agreements. Defining indicators and conceptualisations should be a collaborative, dialogic effort. While our model is primarily based on dialogues between Finnish HEIs and their African partners as well as dialogues among the authors, limiting its universal applicability, it resonates with lessons from literature and experiences of good partnerships (Woldegiorgis & Scherer, 2019; KFPE, 2018). However, we acknowledge the need for further research, testing and refinement across contexts.

Discussion

This study captured the perceptions of individuals within institutions and partnerships engaged in collaboration and co-creative processes. It underscores the importance and interplay of both organisational and relational dimensions in fostering good, meaningful partnerships. While institutions play a crucial role in driving and supporting collaborative initiatives, individual efforts in immediate surroundings are equally meaningful. Additionally, individual perspectives reveal how epistemic hegemonies can be challenged through continuous dialogue and co-creative practices. Embracing diverse perspectives within knowledge communities enriches collaborative processes and strengthens partnerships.

The findings indicate diverse starting points for reflecting on partnerships. We suggest further exploration of how various factors, such as positionalities, professional backgrounds, geographic locations, institutional affiliations and theoretical frameworks, shape perceptions of what constitutes good partnerships. Thus far, it has been evident that the dimensions, definitions, and characteristics of partnerships are interconnected and often overlap in practice. This serves as a reminder to consider both organisational and relational aspects and to give them equal value when reflecting on and developing partnerships. Returning to the metaphor of the butterfly, we acknowledge the uniqueness and fragility of each butterfly and of each partnership. Technical structures and agreements are rarely sufficient to form genuine, sustained partnerships. The butterfly model reminds us of the dimensions and layers of partnerships reaching beyond their technical arrangements and can be used to facilitate discussions on partnership development. We believe that it is important to continue analysing the factors that enable certain partnerships to flourish and grow into high-flying, mutually beneficial and rewarding drivers of action. The butterfly model can help create research designs that capture the diverse elements of partnerships, including the differences between partners and where interests and motivations can meet. Echoing the social constructivist perspective of how reality is (co-)constructed, this article sheds light on how individuals shape their social realities through ongoing dialogues and interactions, emphasising the significance of lived experiences and perceptions. Individuals cannot escape their personal rationalities or the perceptions through which their everyday lives are established: This can create tensions within different knowledge communities and social encounters, such as partnership dialogues. Examining those social moments from a dialogical perspective allowed us to find a framework where multi-voiced realities meet, co-exist and organise socially shared knowledge (Marková, 2016).

Several critical matters relate to developing and sustaining partnerships. First, experiences and learning from HEI collaborations are not sufficiently integrated into these efforts, as Filho et al. (2018) noted. Organisational barriers, such as inadequate funding and rigid bureaucratic systems, hinder flexibility and alternatives that are critical for good partnerships. Sustaining and transforming partnerships requires dialogues with academics from diverse socio–cultural and political backgrounds because ‘sustainability education is specifically promoted through the better understanding of different global issues related to sustainable development, such as extreme poverty, human rights, globalisation, equality issues, professional ethics and environmental challenges’ (Filho et al., 2018, p. 293). Therefore, understanding the socio–cultural and political realities of partners is a critical element in good partnerships. Exchanging contextually rich understandings and experiences can add value to discussions for structuring and transforming institutional partnerships.

Second, this study strongly highlights the relational aspect of developing good partnerships. Critical self-reflection and working on the social relations of development in everyday research engagement are important for decolonising knowledge and enhancing the relevance and impact of research (Keahey, 2020). There is no transformation, institutional, collective, or individual, without social interaction. Hence, HEI collaborations must place relationality at the heart of partnerships. It is important to ask not only whom we partner with but also how we partner with them. While SDG17 encourages partnerships, we must go further and ask what it means to engage as academics from diverse socio–political backgrounds in ways that are ethical, authentic, sustainable, and critical. This critical awareness of structural power dynamics (Keahey, 2020) and scrutiny of how knowledge is created form the basis for adopting a more ethical approach to HE partnerships.

The views of good partnerships are informed by experience, positions, values, and ideals. This study was driven by actors committed to fostering equitable academic partnerships and exploring best practices corroborating with the core values of their institutional DNA. Throughout this process, the underlying principle was based on the premise that partnership, itself, is a core value of any collaboration, a principle that consistently shaped the collaboration within the team. Hence, this study could be described as a series of partnerships based on the fundamental principles of working, learning together and co-creation, driven by conscious decisions and individual choices. Future researchers should further explore how positionalities shape partnership development.

The findings underscore the agency of individuals working within institutional partnerships and question the frequently rigid and externally driven one-way agenda(s) and processes. To advance sustainable development and address global challenges, it is crucial not to undermine the potential of small (knowledge) communities and networks of individuals, often with limited resources, which are engaged in Global South–North HE partnerships. The benefits of co-creation processes often remain at the individual or network level, enriching those involved. However, these benefits may fail to ‘contaminate’ the institutional level if not studied and understood as important for sustaining partnerships and connecting the local with the global. Future research is needed to explore how to harvest the learning that takes place within partnership communities and use it to inform, critically reflect on and transform institutional partnerships and engagement practices.

Conclusion

Previous research has referred to the need to actively challenge power asymmetries in North–South partnerships to ensure more equitable participation. This study highlights that investigating components of stakeholder salience, such as power and its imbalances, requires participants to develop an in-depth understanding of one another’s contexts. Eventually, equitable and reciprocal partnerships should be viewed not just as informative but as relational processes that are guided by principles of equity, mutuality, appreciation, and genuine interest to learn from each other. To achieve this, participants must engage in self-reflection, critically examining their prejudices, biases and the colonial thinking that often underpin South–North partnerships. Actively challenging one’s own thinking is essential for building mutuality. We suggest that active partnerships should extend beyond merely adhering to institutional frameworks unidirectionally. Instead, they should aim to inform and transform institutional frameworks and processes through reciprocal, two-way exchanges. This getting-to-know-you process should extend beyond formal institutional arrangements and engage partners in genuine dialogue that enhances understanding and appreciation of each other’s contexts and expertise. This relational dimension often remains overlooked in practice.

To encapsulate this idea, we present the butterfly metaphor as a generic framework within which to consider partnerships at their different stages, inviting colleagues to work with the metaphor and develop it. We suggest that building an equitable collaboration for sustainability transformation is a process of qualitative maturation, advancement, and continuous co-construction rather than one of establishment, implementation, and facilitation with only goals that can be measured by metrics. We argue that impactful and meaningful partnerships contributing to sustainability transformation should be based on a vision that acknowledges the intertwined nature of organisational and relational aspects where all partners have an active agency in creating collaborative spaces and maintaining the processes.

Creating space for partnership dialogue is necessary in that it facilitates global learning and the creation of context-relevant knowledge for social impact. This, in turn, reinforces the connection between SGD4 and SGD17. Furthermore, our analysis of the elements of good partnerships can contribute to strengthening the indicators for SDG17 by providing analytical tools for those working with and in global partnerships. Viewing partnerships as co-constructed, yet inherently fragile, relationships can increase the importance of HEI partnerships and encourage the development of more robust, mutually beneficial alliances for transforming HE towards sustainability.

References

Aboderin, I. (2024, June 3). Decolonising development studies and the Africa Charter for Transformative Research Collaborations [webinar]. Development Studies Association. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-HBDNSMmjQI

Al-Hazaima, H., Low, M., & Sharma, U. (2025). The integration of education for sustainable development into accounting education: Stakeholders’ salience perspectives. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 37(2), 296–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBAFM-06-2023-0105

Asare, S., Mitchell, R., & Rose, P. (2020). How equitable are South–North partnerships in education research? Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 52(4), 654–673. https://doi.org.10.1080/03057925.2020.1811638

Bell, D. M., & Pahl, K. (2018). Co-production: Towards a utopian approach. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 21(1), 105–117. https://doi.org.10.1080/13645579.2017.1348581

Bender, K. (2022). Research–practice–collaborations in international sustainable development and knowledge production: Reflections from a political–economic perspective. The European Journal of Development Research, 34, 1691–1703. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-022-00549-7

Bexell, M. (2024). Indicator accountability or policy shrinking? Multistakeholder partnerships in reviews of the sustainable development goals. Global Policy, 15, 276–287. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.13348

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE Publications.

Brito Salas, K., & Avento, R. (2023). Ethical guidelines for responsible academic partnerships with the Global South. Finnish University Partnership for International Development, UNIPID.

Connell, R. (2007). Southern theory: The global dynamics of knowledge in social science. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Crosling, G., Nair, M., & Vaithilingams, S. (2014). A creative learning ecosystem, quality of education and innovative capacity: A perspective from higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 40(7), 1147–1163. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.881342

de Groot, L., Demeijer, F. A., Zweekhorst, M., & Urias, E. (2025). Multi-stakeholder networks in the higher education context: A configurative literature review of university–community interactions. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 27(4), 490–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2025.2451445

Eta, E. A. (2023). Social justice and neoliberalising Cameroonian universities in pursuit of the Bologna Process: An analysis of the employability agenda. In I. Kushnir & E. A. Eta. (Eds.), Towards social justice in the neoliberalist Bologna Process (pp. 149-169). Emerald Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80117-880-820231008

Eta, E. A., Stockmann, N., Kontio, H., & Lehtomäki, E. (2024). Global asymmetries in international doctoral education. Dissertations on education development in Africa at Finnish universities. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education, 8(3). https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.5937

Filho, W. L., Raath, S., Lazzarini, B., Vargas, V., Souza, L. D., Anholon, R., & Orlovic, V. (2018). The role of transformation in learning and education for sustainability. Journal for Cleaner Production, 199, 286–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.017

Finnish National Board on Research Integrity. (2023). The Finnish Code of Conduct for Research Integrity and Procedures for Handling Alleged Violations of Research Integrity in Finland. https://tenk.fi/sites/default/files/2023-11/RI_Guidelines_2023.pdf

Guterman, J. T. (2006). Mastering the art of solution-focused counselling. American Counseling Association.

Haelewaters, D., Hofmann T. A., & Romero-Olivares, A. L. (2021). Ten simple rules for Global North researchers to stop perpetuating helicopter research in the Global South. PLoS Computational Biology, 17(8). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009277

Hanada, S. (2021). Higher education partnerships between the Global North and Global South: Mutuality, rather than aid. Journal of Comparative & International Higher Education, 13(5), 135–144. https://doi.org/10.32674/jcihe.v13i5.3686

Harman, S. (2019). Seeing politics: Film, visual methods and international relations. McGill-Queen's University Press.

Hoekstra, F., Mrklas, K. J., Sibley, K. M., Nguyen, T., Vis-Dunbar, M., Neilson, C. J., Crockett, L. K., Gainforth, H. L. & Graham, H. L. (2018). A review protocol on research partnerships: A coordinated multicenter team approach. Systematic Reviews, 7(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0879-2

Hofmann, R. (2020a). Dialogue, teachers and professional development. In N. Mercer, R. Wegerif, & L. Major (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of research on dialogic education (pp. 213–216). Routledge.

Hofmann, R. (2020b). Dialogues with data: Generating theoretical insights from research on practice in higher education. In J. Huisman & M. Tight (Eds.), Theory and Method in Higher Education Research (pp. 41–60). Emerald. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2056-375220200000006004

Kagiri-Kalanzi, E., & Avento, R. (2018). Bridging existing and new approaches for science, technology and innovation cooperation between Finland and Africa (policy brief). UNIPID – Finnish University Partnership for International Development. https://www.unipid.fi/assets/policybriefs/brief_1_africa_web.pdf

Keahey, J. (2020). Ethics for development research. Sociology of Development, 6(4), 395–416.

KFPE (Swiss Commission for Research Partnerships with Developing Countries). (2018). A Guide for Transboundary Research Partnerships: 11 Principles (3rd Ed.). Swiss Academy of Sciences.

Kassie, K., & Angervall, P. (2022). Double agendas in international partnership programs: A case study from an Ethiopian University. Education Inquiry, 13(4), 447–464, https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2021.1923433

Kontinen, T., Oinas, E., Komba, A., Matenga, C., Msoka, C., Kilonzo, R. G., & Mumba, M. (2015). Developing development studies in North–South partnership: How to support institutional capacity in academia? In R. Kilonzo & T. Kontinen (Eds.), Contemporary concerns in development studies: Perspectives from Tanzania and Zambia (pp. 158-167). Publications of the Department of Political and Economic Studies (23), University of Helsinki. http://doi.org/10.31885/2018.00007

Lanford, M. (2020). Long term sustainability in global higher education partnerships. In A. Al-Youbi, A. Zahed, & W. G. Tierney (Eds.), Successful global collaborations in higher education institutions (pp. 87–93). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25525-1_9

Lanford, M. (2021). Critical perspectives on global partnerships in higher education: Strategies for inclusion, social impact and effectiveness. Journal of Comparative & International Higher Education, 13(5), 10–14. https://doi.org/10.32674/jcihe.v13i5.4449

Lebeau, Y., & Oanda, I. O. (2020). Higher education expansion and social inequalities in sub-Saharan Africa: Conceptual and empirical perspectives. UNRISD Working Paper, No. 2020-10, United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD), Geneva. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/246252/1/WP2020-10.pdf

Linnér, B.-O., & Wibeck, V. (2019). Sustainability transformations. In Sustainability Transformations: Agents and Drivers Across Societies. Cambridge University Press.

Luthuli, S., Daniel, M., & Corbin, J. (2024). Power imbalances and equity in the day-to-day functioning of a North plus multi-South higher education institutions partnership: A case study. International Journal for Equity Health, 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-024-02139-x

Mäkinen, S. (2022). Nothing to do with politics? International collaboration in higher education and Finnish–Russian relations. European Journal of Higher Education, 13(2), 216–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2022.2141814

Marková, I. (2006). Dialogue in focus groups: exploring socially shared knowledge. Equinox.

Marková, I. (2016). The dialogical mind: Common sense and ethics. Cambridge University Press.

Mitchell, R., Rose, P., & Asare, S. (2020). Education research in Sub-Saharan Africa: Quality, visibility and agendas. Comparative Education Review, 64(3), 363–383. https://doi.org/10.1086/709428

Mitchell, R. K., Agle, B. R., & Wood, D. J. (1997). Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 853–886. https://doi.org/10.2307/259247

Paavola, S., Lipponen, L., & Hakkarainen, K. (2004). Models of innovative knowledge communities and three metaphors of learning. Review of Educational Research, 74(4), 557–57. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074004557

Redman, A., & Wiek, A. (2021). Competencies for advancing transformations towards sustainability. Frontiers in Education, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.785163

Rolin, K. (2015). Values in science: The case of scientific collaboration. Philosophy of Science, 82(2), 157–177. https://doi.org/10.1086/680522

Schroeder, D., Cook, J., Hirsch, F., Fenet, S., & Muthuswamy, V. (Eds.) (2018). Ethics dumping case studies from North–South research collaborations. Springer Briefs in Research and Innovation Governance. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64731-9

Seehawer, M., & Breidlid, A. (2021). Dialogue between epistemologies as quality education. Integrating knowledges in Sub-Saharan African classrooms to foster sustainability learning and contextually relevant education. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100200

Shenderova, S. (2023). Collaborative degree programmes in internationalisation policies: the salience of internal university stakeholders. European Journal of Higher Education, 13(2), 197–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2022.2120035

Teferra, D. (2016). African flagship universities: Their neglected contributions. Higher Education, 72, 79–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9939-x

Temmerman, R. (2021). Metaphorical models and the translator’ s approach to scientific texts. Linguistica Antverpiensia, New Series – Themes in Translation Studies, 1. https://doi.org/10.52034/lanstts.v1i.16

Tsing, A. L. (2015). The mushroom at the end of the world. Princeton University Press.

Ulmer, N., & Wydra, K. (2020). Sustainability in African higher education institutions (HEIs): Shifting the focus from researching the gaps to existing activities. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 21(1), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-03-2019-0106

United Nations. (2019). Global sustainable development report. The future is now: Science for achieving sustainable development. https://sdgs.un.org/gsdr/gsdr2019

United Nations. (2024). The sustainable development goals report 2024. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2024/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2024.pdf

Unterhalter, E., & Howell, C. (2021). Unaligned connections or enlarging engagements? Tertiary education in developing countries and the implementation of the SDGs. Higher Education, 81(1), 9–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00651-x

Urenje, S., Brunner, W., & Petersen, A. (2017). Development of ‘Fundisana Online’: An ESD eLearning programme for teacher education. In H. Lotz-Sisitka, O. Shumba, J. Lupele, & D. Wilmot (Eds.), Schooling for Sustainable Development in Africa (pp. 275–289). Springer.

Woldegiorgis, E. T. (2021). Decolonising a higher education system which has never been colonised. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 53(9), 894–906. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1835643

Woldegiorgis, E. T., & Scherer, C. (Eds.). (2019). Partnership in higher education: Trends between African and European institutions. BRILL.

Yarmoshuk, A. N., Cole, D. C., Guantai, A. N., Mwangu, M., & Zarowsky, C. (2019). The international partner universities of East African health professional programmes: Why do they do it, and what do they value? Globalization and Health, 15(37). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-019-0477-7