A ‘reverse’ academic drift?

Changes in Swedish educational Crafts

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.7577/formakademisk.5407Keywords:

Craft education, sloyd, digitalisation, educational ecology, primary schoolAbstract

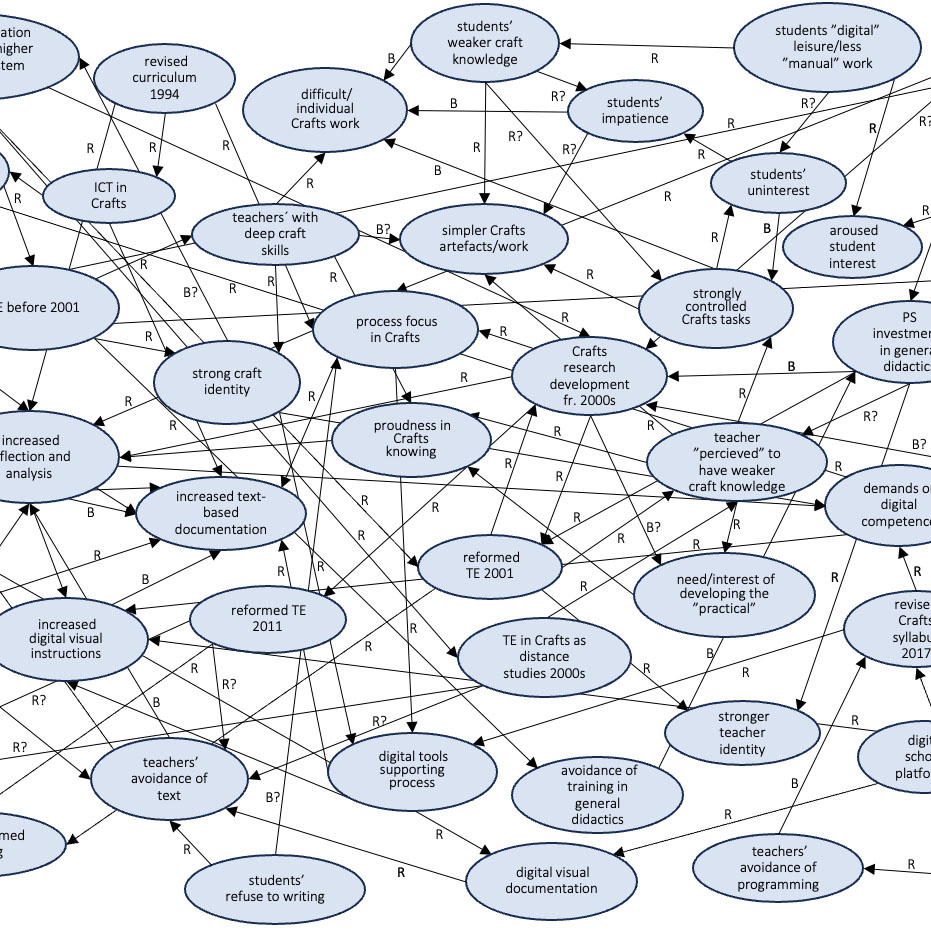

The prerequisites for formal training in Swedish educational Crafts have changed over time under the influence of two long-lasting societal processes: academisation and digitalisation. In different, yet interconnected ways, these processes of change are challenging the materiality, the making and the action-based knowledge that characterise educational Crafts. The paper presents how primary school teachers’ view the influence of academisation and digitalisation in their work and explores the consequences that change processes hold for the teaching practice in Crafts. The study is based on qualitative interviews with Craft teachers whose graduation year was between 1983 and 2021. Theoretically, Craft is considered to be a living ecology in an educational system. In the analysis, academic drift on various levels is combined with media-ecology concepts to clarify the diffusion of academisation and digitalisation in both time and space. The findings show academic drift leading to increased text-based knowledge production on several levels, yet also an unexpected weakening of action-based knowledge in Crafts. Balancing student and staff drift is further shown to result in the avoidance of written text in favour of digital visual, oral and bodily mediations in the production of knowledge. The study’s overall results question an ongoing ‘reverse’ academic drift and what is at stake in the Crafts ecology’s efforts to achieve balance.

References

Andersson, J. (2020). Kommunikation i slöjd och hantverksbaserad undervisning [Communication in handicraft and craft-based teaching]. [Doctoral dissertation, Göteborgs universitet]. Centrum för utbildningsvetenskap och lärarforskning (CUL).

Banathy, B. H., & Jenlink, P. M. (2013). Systems inquiry and its application in education. In J. M. Spector, M.D. Merrill, J. Elen, M. J Bishop. Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (pp. 37–57). Routledge.

Borg, K. (2016). Vem har makten och ansvaret för utveckling eller avveckling av ett skolämne? Reformer och förändringar i slöjdlärarundervisning och slöjdlärarutbildning 1960–2011[Who has the power and responsibility for development or discontinuation of a school subject? Reforms and changes in the teaching of sloyd teachers and sloyd teacher training 1960–2011]. Tilde, 16, 29–86. https://www.umu.se/globalassets/organisation/fakulteter/humfak/institutionen-for-estetiska-amnen-i-lararutbildningen/tilde/rapportserie/tilde_16.pdf

Borg, K. (2021). Tendenser inom slöjdens forskningsområde [Tendencies within the field of sloyd research]. Techne Series A, 28(4), 231–254. https://doi.org/10.7577/TechneA.4738 https://doi.org/10.7577/TechneA.4738

Bryman, A. (2018). Samhällsvetenskapliga metoder [Social research methods]. (3d ed.) Liber.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2010). Research methods in education. Routledge.

Digranes, I., Gao, B., Nimkulrat, N., Rissanen, T., & Stenersen, A. L. (2021). Editorial track 6a. Materiality in the Digital Age. FormAkademisk, 14(4). https://doi.org/10.7577/formakademisk.4663 https://doi.org/10.7577/formakademisk.4663

Ekström, A. (2008). Kroppsligt lärande i slöjdundervisning [Embodied learning in craft education]. In A-L Rostvall & S. Selander (Eds.), Design för lärande. Norstedt.

Elzinga, A. (1997). The science-society contract in historical transformation: With special reference to ‘epistemic drift’. Social Science Information, 36(3), 411–445. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901897036003002 https://doi.org/10.1177/053901897036003002

Erixon, P-O., Jeansson, Å., Westerlund, S., & Wikberg, S. (2023). Diversification and division – ‘academic drift’ in Swedish teacher education in the aesthetic school subjects in a new higher education structure, Education inquiry, (ahead-of-print), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2023.2213473 https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2023.2213473

Erixon, P-O., & Wikberg, S. (2023). Early academic drift in teacher education in the aesthetic school subjects from the 1040s to 1970s – a Swedish case. Arts Education Policy Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632913.2023.2225789 https://doi.org/10.1080/10632913.2023.2225789

Esiasson, P., Gilljam, M., Oscarsson, H., Towns, A., & Wängerud, L. (2017). Metodpraktikan: Konsten att studera samhälle, individ och marknad [Method practice: The art of studying society, the individual and the market]. Wolters Kluver.

Fransson, G., Lindberg, O. J., Olofsson, A. D. (2018). Adequate digital competence – a closer reading of the new national strategy for digitalization of the schools in Sweden. Seminar.net: Media technology and lifelong learning, 14(2), 217–228. https://doi.org/10.7577/seminar.2982 https://doi.org/10.7577/seminar.2982

Goodlad, J. I. (1997). In Praise of Education. Teachers College Press.

Hallsén, S. (2013). Lärarutbildning i skolans tjänst?: en policyanalys av statliga argument för förändring [Teacher education in the service of the school?: A policy analysis of government arguments for change]. [Doctoral dissertation, Uppsala universitet]. Uppsala Studies in Education.

Holmberg, A. (2009). Hantverksskicklighet och kreativitet: Kontinuitet och förändring i en lokal textillärarutbildning 1955–2001 [Craftmanship and creativity: Continuity and change in a local teacher education 1955–2001]. [Doctoral dissertation, Uppsala universitet]. Studia textilia.

Kokko, S. (2022). Orientations on studying crafts in higher education. Craft Research, 13(2), 411–432. https://doi.org/10.1386/crre_00086_1 https://doi.org/10.1386/crre_00086_1

Kyvik, S. (2007). Academic drift – a reinterpretation. In J. Enders & F. van Vught (Eds.). Towards a cartography of higher education policy change. A Festschrift in Honour of Guy Neave. (pp. 333–338). Center for Higher Education Policy Studies (CHEPS).

Johansson, M. (2018). Doktorsavhandlingar inom det nordiska slöjdfältet [Doctoral theses in the Nordic sloyd field]. Techne Series A, 25(3), 109–123.

https://journals.oslomet.no/index.php/techneA/article/view/3031

Logan, R. K. (2015). General systems theory and media ecology: Parallel disciplines that animate each other. Explorations in Media Ecology, 14(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1386/eme.14.1-2.39_1 https://doi.org/10.1386/eme.14.1-2.39_1

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding media: The extensions of man. Routledge.

Nygren-Landgärds, C. (2021). Forskning på bredden av vetenskapsområdet [Research on the breadth of the scientific field]. Techne Series A, 28(4), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.7577/TechneA.4734 https://doi.org/10.7577/TechneA.4734

Saugstad, T. (2002). Educational theory and practice in an Aristotelian perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 46(4), 373–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/0031383022000024561 https://doi.org/10.1080/0031383022000024561

Scolari, C. A. (2012). Media ecology: Exploring the metaphor to expand the theory. Communication Theory, 22, 204–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2012.01404.x https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2012.01404.x

Sedlacko, M., Martinuzzi, A., Røpke, I., Videira, N., & Antunes, P. (2014). Participatory systems mapping for sustainable consumption: Discussion of a method promoting systemic insights. Ecological Economics, 106, 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.07.002 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.07.002

Selwyn, N. (2017). Skolan och digitaliseringen: Blir utbildning bättre med digital teknik? [Is technology good for education?]. Daidalos AB.

Sevaldson, B. (2017). Redesigning systems thinking. FormAkademisk, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.7577/formakademisk.1755 https://doi.org/10.7577/formakademisk.1755

Skjelbred, B. H, & Borgen, J. S. (2023). Formingsforskning i en ny tid? Forskningstradisjon, kunnskapsutvikling og endring i faget kunst og håndverk [Forming research in a new era? Research traditions, knowledge development and change in the Art and crafts subject]. FormAkademisk, 16(2). https://doi.org/10.7577/formakademisk.4813 https://doi.org/10.7577/formakademisk.4813

Swedish National Agency of Education (SNAE). (2022). Läroplan för grundskolan, förskoleklassen och fritidshemmet 2022 [Curriculum for the compulsary school, preschool class and school-age educare]. Norstedts juridik. https://www.skolverket.se/publikationsserier/styrdokument/2022/laroplan-for-grundskolan-forskoleklassen-och-fritidshemmet---lgr22

Sundberg, D., & Adolfsson, C-H. (2015). Att forskningsbasera skolan – en analys av utbildningspolitiska frågeställningar och initiativ över en 20 års period [Basing the school on research – an analysis of educational policy issues and initiatives over a 20-year period]. Vetenskapsrådet. https://www.vr.se/download/18.2412c5311624176023d25a34/1555422926860/Att-forskningsbasera-skolan_VR_2015.pdf

SFS (2010:800). Skollag [The Swedish school act]. Utbildningsdepartementet. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/skollag-2010800_sfs-2010-800

Vliege, J. (2018). Education in a digital age: How old and new technologies shape our subjectivities. Explorations in Media Ecology, 17(1), 57-61. https://doi.org/10.1386/eme.17.1.57_1 https://doi.org/10.1386/eme.17.1.57_1

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2023 Stina Westerlund

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms:

- Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgement of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgement of its initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See The Effect of Open Access).

- The author(s) must manage their economic reproduction rights to any third party.

- The journal makes no financial or other compensation for submissions, unless a separate agreement regarding this matter has been made with the author(s).

- The journal is obliged to archive the manuscript (including metadata) in its originally published digital form for at least a suitable amount of time in which the manuscript can be accessed via a long-term archive for digital material, such as in the Norwegian universities’ institutional archives within the framework of the NORA partnership.

The material will be published OpenAccess with a Creative Commons 4.0 License which allows anyone to read, share and adapt the content, even commercially under the licence terms:

This work needs to be appropriately attributed/credited, a link must be provided to the CC-BY 4.0 licence, and changes made need to be indicated in a reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests that the licensor endorses you or your use.